-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2025; 15(1): 32-56

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20251501.02

Received: May 9, 2025; Accepted: Jun. 6, 2025; Published: Dec. 8, 2025

Effects of Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania

Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, Shubira L. Kalugila, Daniel A. Mbisso

ARDHI University (ARU), Dar–es–Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania

Correspondence to: Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, ARDHI University (ARU), Dar–es–Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The rapid urbanization experienced by most cities in developing countries due to a number of reasons, has been and continues to be in–line with the influx of informal socio–economic activities conducted on improvised planned urban spaces, by urbanites as they struggle to attain their daily basic needs. There are several effects that may be resulted from the conducted socio–economic activities. To understand them, this paper examined the effects resulted by on–going on urban spaces improvisation in the planned settlements, in Dar–es–salaam, Tanzania. It employed a sequential explanatory mixed–methods approach, primarily using quantitative methods, supplemented by qualitative techniques to explain the quantitative data, whereby multiple data collection tools, i.e., questionnaires, observations, photographic registrations and FGD were used. Likewise, it also employed a descriptive case study strategy, focusing on Sinza “A” in Dar–es–Salaam. A total of 110 questionnaires were distributed via stratified random sampling to building owners, tenants, and officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs, with 106 (i.e., 96.4%) properly filled and returned. The collected data were cleaned, coded, processed, in which the quantitative data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics (one–sample t–test). This paper revealed that attaining daily livelihood and human basic needs, an increase in social and economic diversity, an increase in government revenue from property tax and commercial activities, an increase in the land value, and an increase in residents' self–employment, were highly ranked. Also, other effects obtained via an open–ended question, included: unbalanced land use pattern; decrease of outdoor space, e.g., recreation, outdoor cooking space during funeral and other cerebrations, gardening, washing and drying clothes, parking, children playing spaces, etc.; inappropriate blockage of urban public spaces; and pollution caused by uncollected solid wastes, and noises. The paper concludes and recommends that the effects revealed were either positive or negative, with the highly ranked most of them being positive, indicating the significance of improvisation to urbanites in fulfilling their daily basic needs. Hence, awareness among urbanites on adherence to urban planning regulatory frameworks, alongside taking on board all the positive effects, when reviewing urban planning policies, legislation (act), and standards, as well as when enacting all policies under preparation, to deal with the negative effects.

Keywords: Effects, Urban Space, Improvisation, Socio–economic Activities, Planned Settlements, Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania

Cite this paper: Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, Shubira L. Kalugila, Daniel A. Mbisso, Effects of Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania, Architecture Research, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 32-56. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20251501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cities in most developing countries have been, and continue to experience rapid population growth, alongside an influx of informal socio–economic activities, which are often hosted informally on improvised planned urban space, originally intended for different uses. This phenomenon of urban space improvisation, in which planned urban spaces are informally adapted or re–purposed for uses they were not originally designed for, has become a characteristic feature of many cities, especially in Africa and other regions of the Global South. Depending on, the settlement’s nature and locality; the undertaken socio–economic activities; the involved population; as well as the existing urban policy, legislation (acts) and standards; the dynamics of urban space improvisation vary significantly from one settlement to another. As a result, each city or settlement has its own unique story to tell when it comes to the effects resulted from the improvisation of urban space.The effects of urban space improvisation are not uniform; they can be negative or positive to the city or settlement, the urbanites, and the characteristics of the rapidly changing urban spaces, re–created via improvisation. The rapid pace of these changes, occurring within a limited amount of public and private urban space, often places the improvised urban spaces under significant strain, as they are encroached upon by competing socio–economic demands. [87], highlights that, these changes are taking place at an accelerated rate, threatening the integrity of both public and private urban spaces. According to [91], cities are unique and cannot be directly compared, as each urban space is the result of complex interactions between diverse people, institutions, and physical environments. This complexity means that cities are constantly evolving systems, and laboratories of trial and error [25], where; urban planning, city building, and socio–economic activities are continuously re–negotiated and re–defined. These evolving dynamics on improvised urban space create disorder, hence making it difficult for local government authorities (LGAs) to maintain and achieve order in a city, especially when the improvisation of urban spaces becomes a means of achieving socio–economic survival [21].The impossibility is fuelled by its help–yourself status in the accumulation of capital and prosperity [20]. Basically, at its core, urban space improvisation is a creative process, driven by the need to accommodate growing populations and the socio–economic activities that emerge as a result. [19] note that; improvisation enables people to generate practical and innovative responses to challenges arising from inadequate or unavailable urban spaces. In cities experiencing rapid population influx, particularly in the Sub–Saharan Africa, the spatial needs of the urban population frequently outpace the availability of formal, planned spaces. This mismatch between spatial needs and availability often leads to the emergence of informal, often chaotic, uses of urban space, resulting in affecting the cityscape. The global trend of increasing urbanization, particularly in developing countries, exacerbates these issues. As rural populations migrate to urban centres in search of better opportunities, cities experience increased pressure on available space. This, in turn, reshapes the urban landscape, as new socio–economic activities, often informal in nature, begin to dominate. The global urban population is expected to continue rising, with the United Nations (UN) projecting that by 2041, 6 billion or 66% of the world’s population will live in cities [67,78–79].In Sub–Saharan Africa (SSA), urbanization is particularly pronounced, with cities such as Dar–es–Salaam and others projected to reach megacity status by 2034 [53]. This rapid urbanization often occurs in tandem with poverty, unemployment, and the improvisation of urban space, which complicates urban planning and policy–making efforts. It also occurs as a result of rural–urban migration in search for something that exceeds their expectation, i.e., a search for the unexpected and for the unforeseen, due to cityscapes being the primary centres for a number of opportunities and jobs that they possess [36]. To curb this situation, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (2015–2030), preceded by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000–2015), particularly SDGs 11, which aim at making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, have been established as part of a global response to these challenges. Key targets (e.g., target 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 11.6, 11.7, etc.) under this goal include; ensuring access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services; sustainable transport systems and improving road safety to all including vulnerable groups; inclusivity and participatory planning; reducing cities' environmental impacts; and providing universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces [51,75,77–78]. These targets reflect the growing recognition of the importance of urban spaces in addressing the socio–economic challenges of the 21st Century. Even the Habitat III Conference in Quito in October 2016, as per [75], has had its contribution share on the same by setting the targets on the land allocated to streets and urban public space. It proposed that 50% of land should be allocated to streets and public space (i.e., 30% for streets and sidewalks and 15% to 20% for open spaces, green spaces and public facilities).Likewise, an establishment of an Agenda 2063 on “the Africa We Want”, targeting on having an inclusive growth and participatory sustainable development, focusing on eradicating poverty through diversified social and economic transformation, and African people having a high quality of life, a high standard of living, sound health and well–being, has been done. However, many cities, particularly in Southern regions, are far from this target. However, despite these global efforts, many cities, particularly in SSA, are far from this target, as they continue to struggle with rapid urbanization, population growth, unemployment, continuous informality and the improvisation of urban spaces. For example [51], details that; the SSA is experiencing re–shaping as well as a physical change to urban settings from the on–going on rapid urbanization, which has been and continues to grow with its statistics rated fastest globally. The change in urban spaces via improvisation, is resulted from informal miscellaneous socio–economic activities conducted by urbanites, who migrated into cities in search of employment and better basic services. In this context, urban space improvisation alongside its effects, has emerged as a vital yet often controversial aspect of SSA urban life. It reflects the capacity of SSA cities and their residents to improvise by adapting to changing circumstances and utilizing limited resources. However, this adaptability can also result in effects in–terms of disordered, fragmented urban environments that challenge formal urban planning and governance. The on–going encroachment of informal activities into planned urban public spaces, such as road reserves, railway lines, and other urban commons, as well as its allied improvisation effects, is a clear indication of the need for more flexible and inclusive planning systems that can accommodate the diverse and ever–evolving needs of the urbanites in SSA [72]. One of the countries experiencing the same is Tanzania, where cities such as Dar–es–Salaam are experiencing rapid urban growth [53,54]. The country’s urban population share has increased dramatically, from 5.7% in 1967 to 29.1% in 2012, and it is projected to exceed 50% by 2050 [42,43], in which its total population is also projected to be 68.6 million by 2050 [53]. As Tanzania’s cities continue to urbanize, the demand for urban spaces to accommodate miscellaneous socio–economic activities and meet basic needs has also been and continues to intensify [7]. The intensification arises along with the need for planned urban spaces that can host these activities in order to meet human basic needs, vs. unemployment. However, planned urban space in these cities remains in short supply, with space improvisation often being the only means by which people can access resources and livelihood opportunities [54], hence ending up invading planned urban spaces. This dynamic has led to the introduction of long–term Development Vision 2025, followed by long–term Development Vision 2050, both aiming at building a resilient and inclusive economy, as well as enhancing the quality of life for all citizens, [80,85]. These long–term plans recognize the importance of informal socio–economic activities, aiming to integrate them into broader economic and spatial planning frameworks. That is why some of country’s policies emphasizes poverty reduction and eradication, employment creation, and the formalization of the informal economy, etc., as key parts of their objectives. Similarly, the country has had three (03), Five–Year Development Plans (FYDP) i.e., FYDP I (2011–2016), FYDP II (2016–2021), and the current one FYDP III (2021–2026) conceived to implement the long–term Development Vision 2025, addressing issues related to; employment creation, poverty reduction and eradication, formalization of the informal economy, housing, human settlements, land management, etc., [85]. However, weak implementation and lack of institutional synergy have left many of these goals unrealized.Despite the efforts to address these issues, much of the informal urban growth remains outside the formal planning system, contributing to the continued informalization of planned settlements by improvising, which leads to a number of effects. As a result, it is crucial to better understand the effects behind urban space improvisation, particularly in planned settlements where urban space is often inadequate or ill–suited to the needs of the urbanites. Thus, this study examines the effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlements, in order to gain a deeper understanding, essentially for developing more effective urban planning regulatory frameworks. This knowledge will inform planners and urban planning policies in dealing with the effects posed by informal parcelling and the use of urban spaces via improvisation. Ultimately, this would lead to more inclusive and sustainable urban development strategies that are adaptable to the needs of the urban poor, and those in need of urban space for hosting their miscellaneous socio–economic activities. The study extends further from [63], using different study locations, sample types, sample size, methodologies, and analytical angles, in order to fill the knowledge gap, alongside informing conventional urban planning and design as well as policy formulation for sustainable development.

2. Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements

- The definitions of space, improvisation, space improvisation in urban cities, its effects, public realm, urban city form, structure, and function, socio–economic activities, urban informality, and unplanned and planned settlement were all determined by reviewing the literature.

2.1. Space

- As highlighted by [49,70], space is “an amount of an area or of a place that is empty or available for use; i.e., the whole area in which all things exist and move”. It is an urban area or an urban place or a totality system of the public realm where people or individuals with multiple political, cultural and socio–economic backgrounds or status, can access, interact, exchange and conduct their daily political, cultural and socio–economic activities, with each other and their surroundings in the urban context [6,9]. Further elaborating on this concept, [6,70] describe space as a void that surrounds us, and it contains different scales; i.e., a room, a house, the street, squares, parks and gardens, playgrounds, neighbourhood, settlements, quarter, city, country and even the rest of the world. According to [21,61,70], space is amorphous and intangible; however, we can feel it, know it, explain it, and it can be sliced up to be improvised and used informally for various socio–economic activities in which some may degrade it and eventually destroy it. The slicing is possible because every space can have one or more functions either in–terms of occupation or movement [91].

2.2. Improvisation

- Improvisation, being the key feature of cities as per [57], its word originates from the Latin word “improvisus”, which means “the unforeseen” [24,57,86], without or absence of a provision [35,36], or unpredictable, as per [47]. It is a process or an ability to create and implement something or a series of unplanned activities or solutions that have not been agreed on, or planned or stipulations made beforehand; hence, ending–up presenting themselves as unforeseen and unexpected [35,36,47]. Moreover, it is the provision of alternatives to all things, which can be in the form of an addition, an adaptation, a change, etc., in response to unanticipated situations that are outside the prepared institutional and regulatory boundaries [35,72]. Improvisation is practised in a variety of domains, including music, dance, and theatre [36], as well as architecture and urban planning. [36] details that; improvisation, apart from being a process which is always misunderstood, is a relatively understudied aspect of creativity and cognition that offers a kind of disorder (e.g., informal use of planned urban spaces), which can benefit city life. A common interpretation is that/ when something is improvised, it is to make up for the lack of something, or to get by in some way until the plan that was lost, can be recovered [36]. Additionally, [36] highlights that improvisation has to do with how people take shortcuts between the formal paths, whereby it may not be preceded by a plan, but by experience and processes of preparation. He adds that; it is a subversive nature of acting in the moment, by which users reappropriate space organized by powerful strategies and techniques of socio–cultural production. According to [35,36], in a controlled framework, improvisation is expressed clearly as a spontaneous intervention, and a process characterised by a simultaneity of conception and execution or action. [19] stress that; improvisation, by its nature, occurs at the intersection of action and cognition.

2.3. Space Improvisation or Improvisation of Space

- In the context of this study, “space improvisation” refers to an act and the process fuelled by residents in the planned settlements, who illegally invade, move into, spontaneously subdivide and use various planned urban spaces for different unplanned socio–economic, cultural and political spatial needs or activities, just to take shortcut from the formal institutional and regulatory system, to cater for the lack of urban space, and meet their daily basic needs. Moreover, [86] asserts that, whether major or minor, improvisation involves the embellishment of something, and for this study, it is the embellishment of urban spaces in planned settlements which is paid attention to. Hence, space improvisation as per [14] involves a form of organizing spaces in order to host activities that are not considered by the planning discipline. [57] detail that; improvisation works with what is available, whether it is caused by a less–than–concrete city plan, a half–functioning planning policy, legislation (acts) and standards1, a nasty yet dominant moral code, or an infrastructure that no longer meets people’s needs.According to [24], space improvisation often takes place in settlements, and it is understood as an intuitive, spontaneous and responsive activity, that offers spaces which accommodate activities that the planning scheme fails to offer. Meaning, from conception or planning and execution, action collapses into a single moment in–terms of time and space; i.e., they happen simultaneously, with no actual or specific plan for a space to be used at that moment, but rather motivated by lack or absence of plan [36]. It has to do with “making the most from an originally planned space, by informally adding more use to it, to get the most out of it”, outside state control, and beyond the existing institutional as well as regulatory framework. Simply, it has to do with the informal production of urban spaces in planned settlements. Improvisation allows for a shift from mono–function to multi–function use of urban spaces, while managing the limited available resources, alongside allowing things to continue in difficult conditions [40].

2.4. Space Improvisation in Urban Cities

- According to [36], improvisation and the city have been intertwined throughout history. With the city being a product of everyday practises [14], i.e., what its residents actually make of it every day [36], and if we see it as in a permanent tension between the built, fixed and rigid on the one hand, and engines of creation, loci of crises, sites of the surprising and unexpected on the other [3], then improvisation is never far [57]. It is so because, via space improvisation, cities can be improvised and transformed over time, as well as changed from their original form, with the key actors actively involved in the shaping process being their people, governed by several planning policies, legislation (acts) and regulations. In most cases, the space improvisation changes the form of the city formally as well as informally, creating planned and unplanned settlements. It may also change the form of the planned settlements, informally, making it interesting to know the effect of urban space improvisation in relation to the socio–economic activities carried out on improvised urban spaces.

2.5. Effects of Space Improvisation in the Planned Settlement

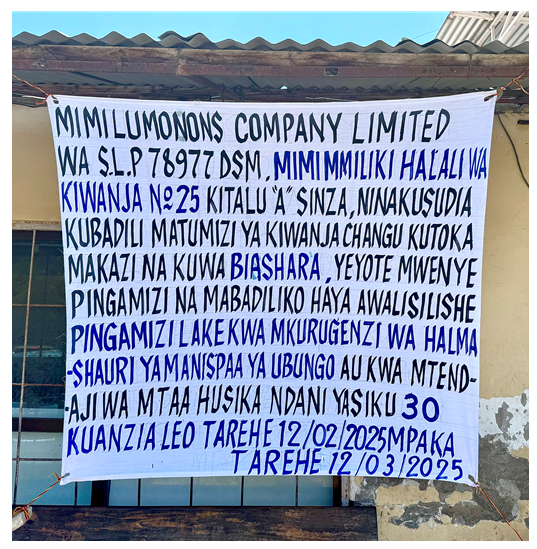

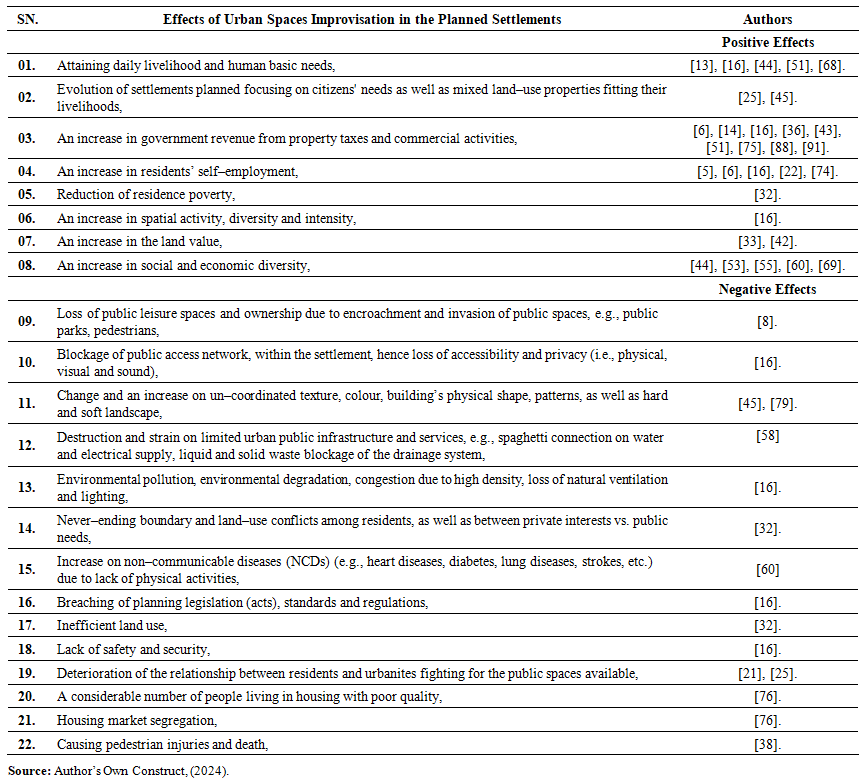

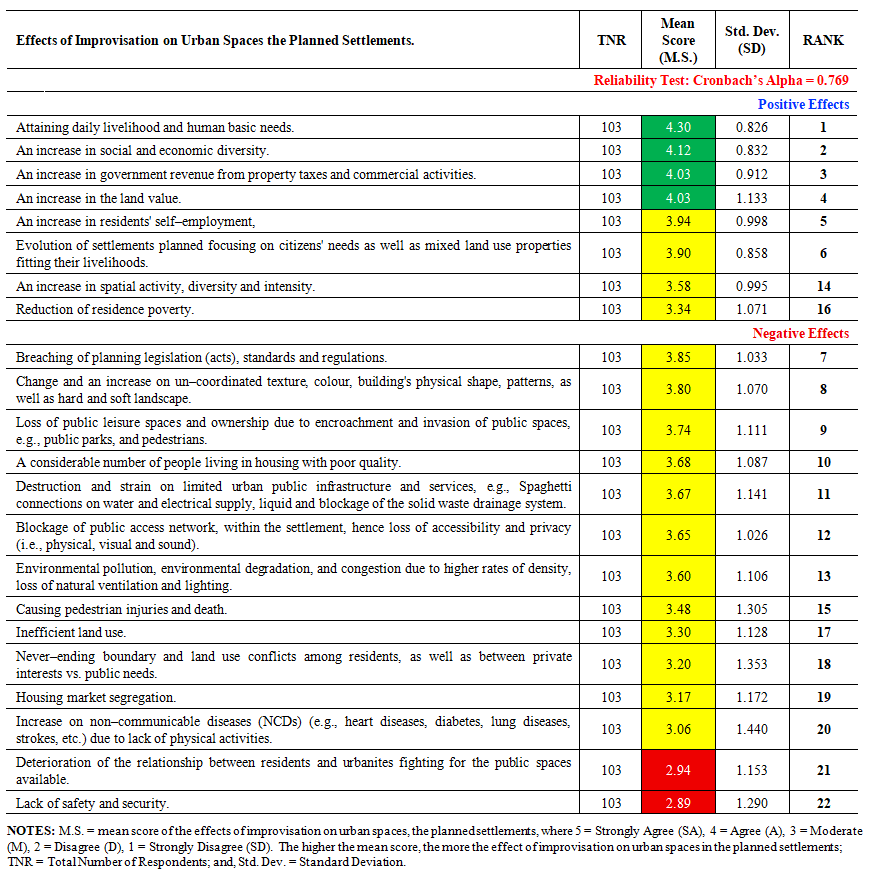

- According to [60], the loss and modification of public spaces due to improvisation have many potential negative impacts, as public spaces perform numerous functions that affect physical urban settings and socio–economic factors. It largely affects the person–place bonds and connection with places that are important to residents and non–residents [61,65]. From the reviewed literature, a list of established effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlements, is as presented in Table 2.02, below: –

| Table 2.02. The effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlement |

2.6. Socio–Economic Activities

- Fundamentally, social activities involve interactions, connections and coming into contact and meeting different residents and non–residents, whereby it could be during participating in community activities, funerals, weddings, sports, work, etc. Meanwhile, economic activities involve activities related to production, purchasing (i.e., buying), exchange, or selling different services and products or commodities, like vegetables and food products from agricultural activities, clothes from the tailoring activities, and boutiques or fabric sellers. Other includes stationery; food and drinks from fast–food restaurants, bars, and pubs; products from shopkeeping activities; different kinds of meat from animal grazing activities; building hardware materials and steel for construction activities, furniture production, door and window burglar–proof or grills production; renting of rooms and houses, etc. Thus, a combination of social and economic activities is what is known as “socio–economic activities”. These two activities complement each other (i.e., they go together). As a result, socio–economic activities refer to all economically viable business and employment–related activities, driven by existing social relations and activities, to attain human basic needs. Its factors include: income, education, employment, occupation, community safety, living conditions, family size and relationship, social support, etc. These socio–economic activities can be undertaken formally or informally, within the urban spaces in a planned settlement. In this study, only informal socio–economic activities will be explored, due to their contribution to improvising urban spaces in planned areas.

2.7. Urban Informality

- Urban informality is a complex, multidimensional concept that cannot be accurately and/or thoroughly defined [28]. Despite countless struggles by [28], in defining of the term remains contested and context–dependent. For this study, however, a working understanding of urban informality is drawn from the collective definitions offered by [9,30]. They define urban informality as socio–economic activities and spatial usage that operate outside the formal urban planning regulatory framework as well as state control. These practices, often in violation of the existing laws and planning codes, are predominantly undertaken by certain groups of people with limited working and economic capability, or low–income groups with limited access to formal employment and housing. Examples include: petty traders, street vendors, coolies and porters, informal artisans, messengers, barbers, shoe shiners, and various service providers operating in streets, alleys, and other improvised public spaces. As [28] notes, cities act as magnetizing centers of economic and job opportunities, particularly because informal systems enable diverse socio–economic engagements and foster social interaction across class and cultural lines. In this context, informality becomes a form of urban improvisation, a set of dynamic, adaptive practices that reshape urban space in response to economic necessity and systemic exclusion.The work of [9,30] further expands on this view, arguing that; urban informality is not an exception but rather integral to the everyday life of African cities. It represents a "new way of life" where informal socio–economies play a dominant role in urban livelihood systems, particularly for the urban poor. In such settings, informality becomes a coping mechanism, providing employment, affordable shelter, and essential services that are largely inaccessible through formal urban channels. However, as [30] cautions, this informality raises critical questions about the right to urban space, especially in relation to who has the power to access, occupy, and transform public space. The ability of informal actors to bypass, circumvent, or transgress planning standards, building codes, and zoning regulations reveals the contested nature of urban governance and spatial justice.Basically, urban informality has been most closely associated with unplanned or informal settlements. These areas emerge and expand without official sanction, often on marginal or underutilized land, and are typically characterized by dense construction, lack of basic infrastructure, and the improvisational use of space to meet daily needs. While these settlements have long been sites of informal activity, recent trends indicate that urban informality is no longer confined to unplanned areas. Increasingly, informal practices and spatial improvisation are spreading into planned settlements, blurring the boundaries between formal and informal urbanism. The encroachment of informality into planned settlements, is evident through the ongoing improvisation of urban space in otherwise formally regulated neighbourhoods. This includes the informal extension of buildings, conversion of public space for commercial or residential use, informal vending zones in formal streetscapes, and unauthorized service infrastructure. Such transformations suggest that even within the boundaries of formally planned settlements, residents are actively reshaping urban form in response to evolving needs, economic pressures, and gaps in governance.

2.8. Unplanned and Planned Settlement

- The in–depth elaborations on unplanned settlements in comparison to planned settlements, as highlighted by [71], can be based on definition, their typological categories and locational existence, projection or growth, formation, characteristics, etc. But briefly, “unplanned settlements”, also known as informal settlements, or slums, or squatters, or low–income settlements, or unauthorized settlements, or uncontrolled settlements or semi–permanent settlements, or spontaneous settlements, as per [28,71], refers to partially or fully unauthorised housing settlements that emerge organically outside the formal urban planning regulatory framework. They accommodate a wide range of socio–economic groups of people from low– middle– and high–income earners (predominantly the low–income earners). They are built incrementally by residents themselves, without adherence to the official range of regulatory standards for planning, land use, and health and safety. In Tanzania, specifically Dar–es–Salaam, which is the study locality, their formation in number has dramatically tripled from 40 settlements in 1985, to over 150 by 2003, and is expected to further increase resulted by the city hosting the largest seaport, as well as industrial and socio–economic activities [27]. Also, their formation increases, which is triggered by rapid urbanization growth experienced by the city, i.e., a growth of 4.3% from 1998 to 2002, 5.6% from 2002 to 2012, and 4.5% in the period of 2015 to 2020 [50,71]. They add that; this increase overwhelms the capacity of the formal housing sector, pushing more residents into improvisation of spaces. That is why, the increased population often end up being absorbed into unplanned settlements, which accommodate 70% and 80% of the Dar–es–Salaam city’s population, and 80% to 90% of urban residential housing stock as per [6,27,34,50,71,83]. This concentration of people and socio–economic activities lead to the intense improvisation of space, as residents adjust organically, by building incrementally, repurposing urban spaces in ways that suit their daily life and survival. As a result, it has made some unplanned settlements near the city centre, to end–up having densities exceeding 300 persons per hectare, [34], using the available urban spaces extensively, resulting in highly compact and multifunctional spaces, hence pushing urbanites into leapfrogging to the planned settlements, to meet their daily basic needs. This urban improvisation, while typically seen as a manifestation of spatial disorder, also reflects a form of bottom–up planning where residents adaptively shape their environment in response to need and opportunity. Meanwhile, planned settlements, also known as formal settlements, refer to authorised housing settlements which are planned and developed within a regulatory framework established by the government planning authority. They are structured with a predefined layout, which includes adequate infrastructures such as; access roads, storm water drainage system, electric supply, water supply, solid waste management systems, urban furniture, street lights, then in most cases are inadequate in unplanned settlements. Generally, as far as a settlement being planned before being occupied by developers is concerned, planned settlements are contrary in most parts from unplanned settlements. Despite their formal status, many planned settlements experience encroachment by informal socio–economic activities. This informality within planned settlement is a growing theme in urban discourse, but remains under–researched. In many cases, the failure of planned settlements to remain strictly “planned” in function or use reveals how improvisational practices extend beyond unplanned settlement, as they normally co–exists side–by–side. The spatial proximity results in cross influence, spilling informality into the planned settlements, in–terms of undertaken socio–economic activities, land use practices. Thus, this study focuses specifically on examining the effects caused by the improvisation of urban spaces within planned settlements.

3. Methodology

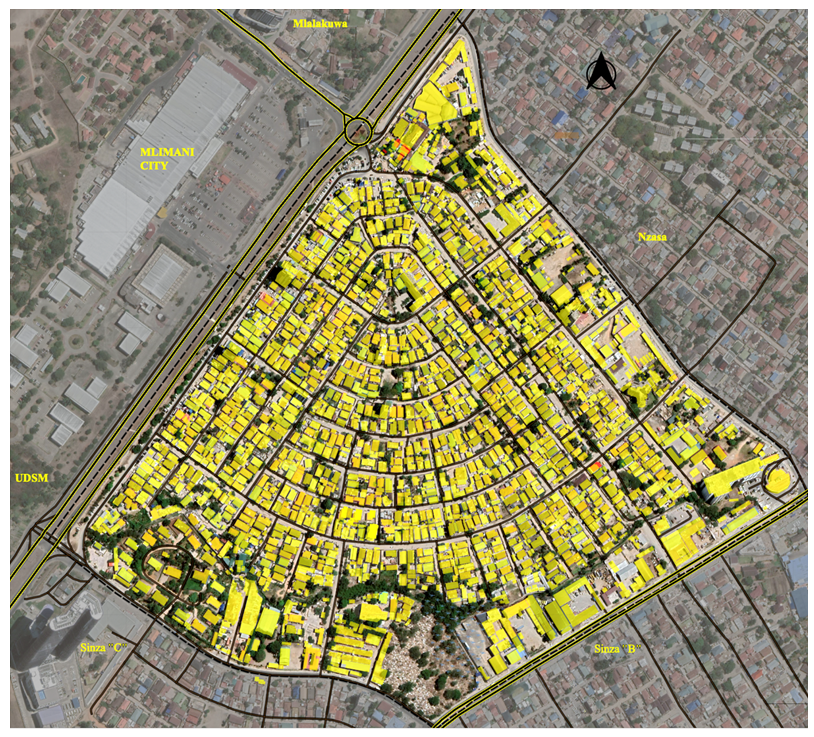

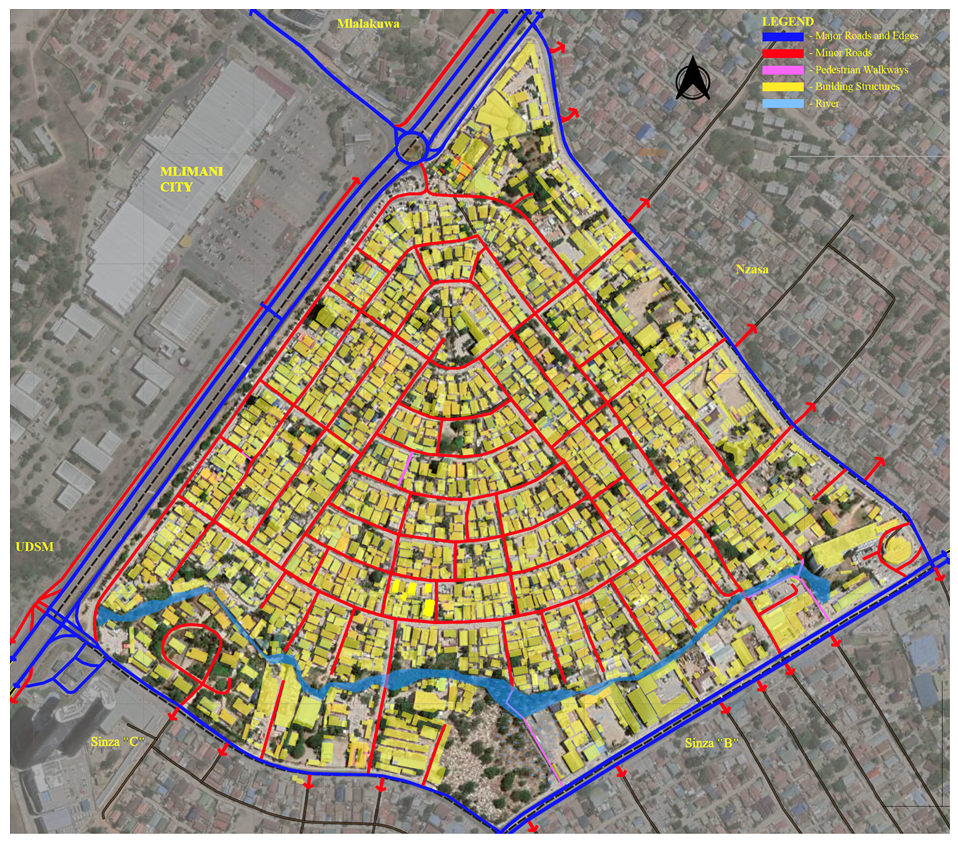

- In–line with writings by [37,39,48,89], and for triangulation reasons, the methodology and research design employed in this study involved a sequential explanatory mixed–methods approach, in which apart from literature review; instruments like questionnaire, and focus group discussion (FGD) were used by approaching various residents and non–residents in–terms of building owners, tenants, as well as government officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs. The unit of analysis is based on urbanites utilizing urban spaces within Sinza “A” planned settlement in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania. The case study was employed because it can bring an understanding of a complex issue or object, and extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research, and it emphasize detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships, as also detailed in [26]. Likewise, in this study and based on QUAN. and qual. strategy as per [48], quantitative data were highly emphasized, while the qualitative data provided a supplementary role to the quantitative findings, in–terms of assisting in explanations. This option made it easier to determine the intended objective, samples and design of the study, as well as ranking the effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlements. For the qualitative part of the study, the researcher was inspired by grounded theory, which aimed at understanding the processes behind urban space improvisation, experienced by each respondent, in order to refine the existing UDD theory.A single case study approach was employed, despite [20] denoting how it is lowly regarded or simply ignored within the academy. Basically, it is ok to select a single case study, as per [12,62,90], because; it reveals more information alongside offering a much deeper investigation than multiple case studies, which dilutes the overall analysis. It offers an in–depth understanding of the effects of the phenomenon, and it has high conceptual validity [20]. Besides, [12] concretize that; the more cases an individual studies, the less the depth in any single case. Additionally, in most cases, a single case approach is selected due to its criticalness, extremeness, typicalness, revelatory power, or longitudinal possibility [90]. Again, a study by [20] observed that; “case studies”, especially in social science, are likely to produce the best theory, because findings are generated using real–life experiences and practices. Moreover, a single case study approach was opted because; the most treasured classic knowledge, and much of what we know about the empirical world, were produced using the same methodology [20]. He further exemplifies that; the most important knowledge generated by Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in Physics, Charles Darwin in Biology, Galilei Galileo on the Law of Gravity, were all contributed from studies carried out using case study as one of the methodologies; hence underlining that; it is one of the critical and most useful methodologies in research. And, its results from a single case study, can be generalized given the fact that knowledge is transferable. [62] concludes that; single case study is often used to understand extreme or unusual instances. Generally, Sinza “A” was selected as a case study area because it is unusual, extreme, and has enough information to present an in–depth detailed depiction regarding urban space improvisation; hence offering an in–depth description and understanding of the studied issue, alongside expanding urban theories.

3.1. Data Collection Methods

- Generally, both primary and secondary data collection were done using multiple data collection tools, as detailed by [37,39,46,89–90]. Questionnaire survey, FGD, non–participatory or physical observations and photographic registration were used to collect primary data from the primary source (first hand), i.e., residents and non–residents in–terms of building owners, tenants living inside and outside the area, as well as government officials from LGAs (i.e., Municipal, WEO, and MEO), CGAs, and MDAs, in which the respondents answered the questions on their own. Some of the questions in the questionnaire were closed–ended and others were open–ended for the respondent to attest their own opinion, and give in–depth information. Besides, secondary data on effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlement, were gathered from literature review via review of documentary reports, unpublished and published peer–reviewed books, journals, articles and papers.

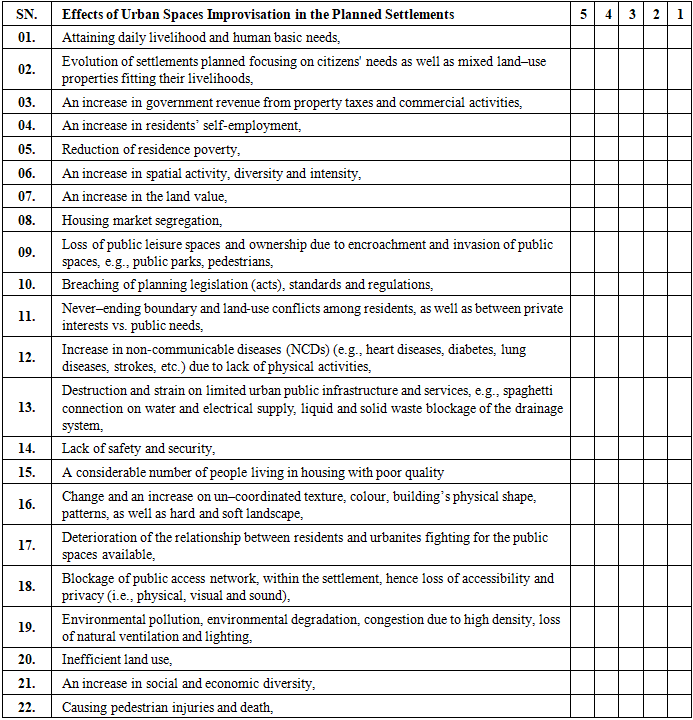

3.1.1. Questionnaire Design

- In this descriptive study, the employed and interactive the self–completed survey questionnaire was prepared in accordance with the research objective, as written by [40,64]. The questionnaire involved both close–ended and open–ended questions, striving to uncover the effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlements, and it was divided into two (02) sections, which covered: – Section A requesting on respondent’s general demographic information; and Section B covering the effects of urban space improvisation in planned settlements. The closed–ended questionnaire was developed based on the refined list mentioned earlier, following a pilot study. Closed–ended questions were chosen for their ease in gathering factual data and simplicity in analysis, as the possible responses are limited [1]. Additionally, open–ended questions were included to gather more detailed feedback from respondents. The questionnaires were edited for completeness and consistency, checked for errors and omissions, as well as being filled out completely. The pilot study was conducted to enhance the quality of the questionnaire and increase the reliability of the questions. It involved identifying twenty–two (22) effects of urban space improvisation, Sinza “A”. The effects were all gauged on a five–point Likert scale, and by using [39] writings in scaling; the respondents were asked to respond to each statement, by indicating with which statement they do, Strongly Agree (SA) = 5, Agree (A) = 4, Moderate (M) = 3, Disagree (SD) = 2, or Strongly Disagree (D) = 1. Likewise, it also employed a descriptive case study strategy, focusing on Sinza “A” in Dar–es–Salaam. A total of 110 questionnaires were distributed via stratified random sampling to building owners, tenants, and officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs, with 106 (i.e., 96.4%) properly filled and returned. The collected data were cleaned, coded, processed, and later analyzed by using IBM SPSS version 25, with an inner reliability for quantitative data tested using Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient, in which the results must be above 0.70, guaranteeing an internal consistency of the information, which was a comparatively elevated internal consistency, suggesting the scale is accurate. This is due to the fact highlighted by [48] that; the Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient value of greater than or equal to 0.70 is considered to be the minimum for an appropriate test, and any quantity less than 0.70 suggests poor reliability. Likewise, a one–sample t–test (μ = 3.5) was conducted to test effects that were statistically significant at a p < 0.05 for those with a Likert Scale of 5.

3.1.2. Focus Group Discussion (FGD)

- The FGD, basing on [23,40,46,64], was employed and conducted with thirteen (13) LGAs, residents and non–residents, selected using non–probability sampling, and the FGD took approximately 45 minutes. The number coincides with [23,40,64], who highlights that; the optimal number of participants in a single FGD is approximately between three (03) and twelve (12), and it should last not more than 90 minutes, out of consideration for the participants' time, to capture robust information. During the FGD, the researcher, as proposed by [48], moderated the discussion on the effects of improvised urban spaces in the planned settlements, while being assisted by the research assistant, who took notes and recorded the discussion. As insisted by [46,89], who warned of the risk of dominant participants, the researcher politely, tactfully, and in a firm style controlled and managed overtalkative individuals (e.g., by throwing kind jokes) to stimulate and encourage quieter participants without biasing the discussion. When the group became silent, gentle as well as kind words were used to reinitiate conversation without biasing its direction. Additionally, [23] adds that; one well–conducted FGD, may be better than two or more, that are less effective.

3.1.3. Observations

- Basing on [12,40,46,64]; the non–participatory or physical observations was employed in this study in gathering the information required through; watching, listening, and record by documenting the on–going on activities, behavior, events, interactions, or physical characteristics in their natural occurring setting, without interviewing participants, to examine the effects of urban space improvisation in Sinza “A”. The employed data collection method was achieved with the assistance of the prepared observation guiding instrument, which covered the researched issues.

3.1.4. Photographic Registration & Sketches

- To document the ongoing urban space improvisation in various parts of Sinza “A”, and present its trend, the study's photographs, sketches, and maps were carefully taken and recorded. Additionally, according to [89], this data gathering approach was opted due to being the most effective tool on which observation may rely.

3.1.5. Review of Documentary Reports

- The study's examination of the documentary report included secondary data that had already been gathered and statistically processed by another party [11,48]. Data from official government reports, national census reports, reference books, theses, journal papers, periodicals, newspaper stories, reports written by academics, and databases already in existence were all included, whether they were published or not. In essence, this study analysed several documentary reports that were based on policy, planning laws and standards, urban space improvisation, space types, and space use.

3.2. The Study Population and Sample Size

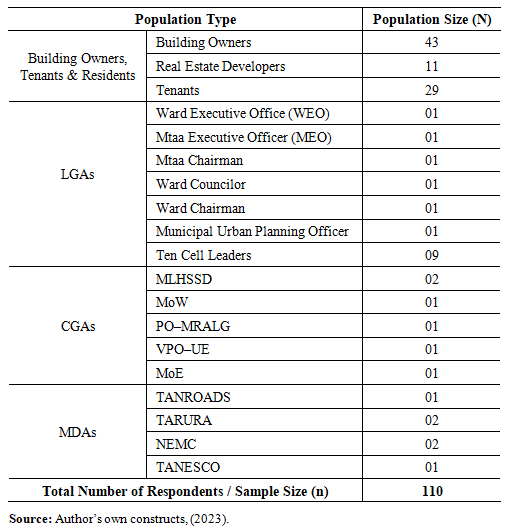

- As highlighted by [36,40,48,56], in order for the results of the study to be generalized, the study sample population must at least share one characteristic or have similar traits that the researcher can observe, identify, and study. In this study, the sample population included; residents and non–residents (i.e., building owners, tenants, real estate or property developers, living insides and outside the settlement), as well as government officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs (i.e., ward counsellors, ward chairman, WEO, MEO, ten–cell leaders, municipal and ministerial official e.g., Town Planners, Engineers etc., officials from MDAs e.g., TARURA, NEMC, TANESCO, TANROADS, etc.), as shown in Table 3.01. As a result, the study sample size was thus determined by stratified random or probability sampling, based on the writings by [20,40,89]. Respondents were separated into homogeneous subgroups, such as residents, such as building owners and tenants living in the area; non–residents, such as business operators and tenants living outside the area; LGA officers from Municipal, WEO, and MEO; CGA officers from Ministries and MDAs, etc.), and then randomly selected from each subgroup. Technically, the sampling selection aimed at (a) keeping the sampling error to a minimum, (b) avoiding systematic biases in the sample, and (c) the study’s intention on generalizing its findings numerically to the entire population of units [20,89]. With the study unit of analysis being residents (i.e., residents, e.g., building owners and tenants; WEO, MEO; and non–residents, e.g., business operators; etc.) living and working in buildings within the case study area, as well as CGA officers from MDAs and LGA officers from Municipal. Thus, it was important to identify the sample size from the existing buildings, which represented a respondent from each selected existing building within the case study areas (Sinza “A”).

| Figure 3.01. The existing buildings within the case study area (i.e., Sinza “A”), Source: Fieldwork & Google Earth, (2023) |

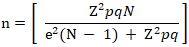

Where: n = the Sample SizeN = the Total Population Size, i.e., = 1879Z = the Confidence Interval Level, i.e., = 95% (1.96)e = the Level of Precision or Margin of Sampling Error, i.e., = 5%p = the Degree Variability, i.e., = 50%q = 1 – p.As indicated above, the data used in sampling are confidence level (Z) – 95% (1.96) and level of precision or margin of sampling error (e) – 5%. A study by [31] shows that; these values are economical to use, and they have been used in various studies, including theirs. Essentially, the decrease in confidence interval level is equal to an increase in the chance of error. For example, if the confidence interval level is 90%, it means the change of making errors is high, i.e., 10%, than when the confidence interval level is 95%, due to the chance of making errors being less, i.e., 5%. From the formula above, the calculated sample size (n) for the residents = 82.887, i.e., 83. The obtained residents' sample size was then combined with the key respondents’ sample size to obtain the study’s total sample size (n) of 110 (as seen in Table 3.01).

Where: n = the Sample SizeN = the Total Population Size, i.e., = 1879Z = the Confidence Interval Level, i.e., = 95% (1.96)e = the Level of Precision or Margin of Sampling Error, i.e., = 5%p = the Degree Variability, i.e., = 50%q = 1 – p.As indicated above, the data used in sampling are confidence level (Z) – 95% (1.96) and level of precision or margin of sampling error (e) – 5%. A study by [31] shows that; these values are economical to use, and they have been used in various studies, including theirs. Essentially, the decrease in confidence interval level is equal to an increase in the chance of error. For example, if the confidence interval level is 90%, it means the change of making errors is high, i.e., 10%, than when the confidence interval level is 95%, due to the chance of making errors being less, i.e., 5%. From the formula above, the calculated sample size (n) for the residents = 82.887, i.e., 83. The obtained residents' sample size was then combined with the key respondents’ sample size to obtain the study’s total sample size (n) of 110 (as seen in Table 3.01). | Table 3.01. The study population (building owners, tenants, officials from LGAs and CGAs, as well as officials from Ministerial Departmental Agencies (MDAs) |

4. Results, Analysis & Discussion

- The main issues covered in this study involved an examination of the effects of improvised urban spaces in planned settlements.

4.1. Survey Administration

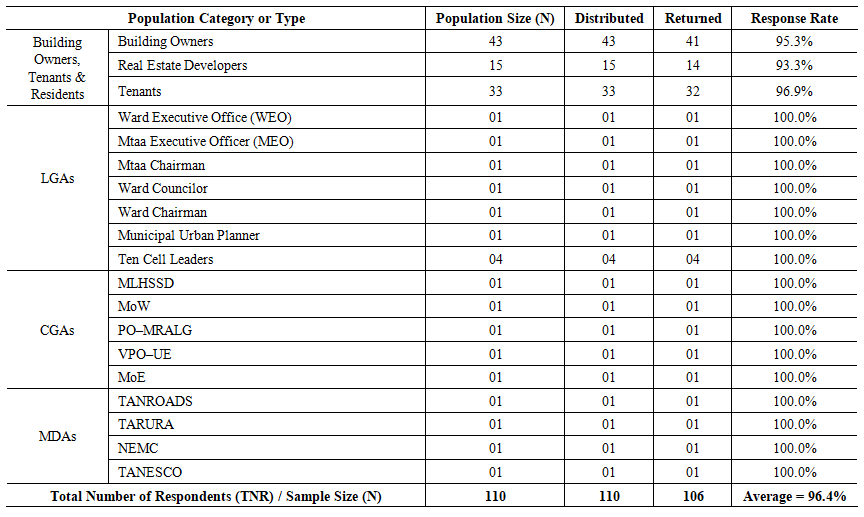

- To improve the quality of obtained answers, as well as the rate while lowering respondents' levels of annoyance, a structured questionnaire with five (05) Likert scales was used in this study [4]. As seen in Table 4.01, a total of 110 questionnaires were distributed to the targeted respondents. In essence, only 106, i.e., 96.4%, of the questionnaires were returned; of these, 102 were used for analysis, with four (04) questionnaires being excluded as they were incomplete. Basically, the acceptable response rate of 96.4% on the returned questionnaire supports the findings of [56], who state that; a response rate of at least 50% is statistically significant for analysis and publicity, with a response rate of 60% being good, in which a response rate of 70% or more, accounted as exceptional. In a similar vein, [66] both state that surveys should aim for a response rate of at least 30%. Furthermore, as noted by [48], a higher response rate indicates greater representativeness of the target population; yet, a low response rate, i.e., less than 50%, may render the study unsatisfactory, unacceptable, and raise validity concerns.

| Table 4.01. The response for the questionnaires distributed to the respondents (building owners, tenants, officials from LGAs, CGAs, and officials from Ministerial Departmental Agencies (MDAs) |

4.2. Data Analysis

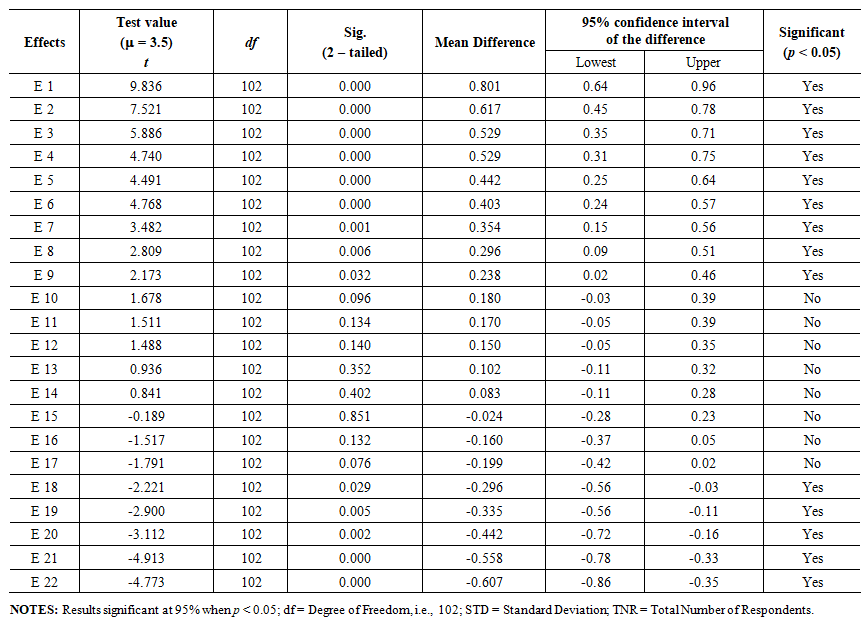

4.2.1. Quantitative Analysis (Questionnaire Survey)

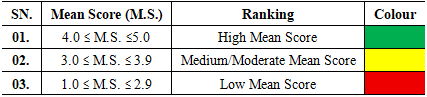

- The IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25 was used to clean, code, process, and then descriptively statistically analyze the collected data. Mean score analysis and standard deviation were computed, resulting in a ranking of the effects in descending order following comparison, as seen in Table 4.02. Additionally, Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient was used to test and verify the quantitative data's reliability, with its result being above the value of 0.70. The effects were statistically significant at a p < 0.05 for those with a Likert Scale of 5 at a 95% confidence level were measured using a parametric test, such as the one-sample t-test (μ = 3.5), with μ serving as the test value. Also, in order to obtain more precise calculations that mapped out a pattern or link between measured or comparable variables, the results were also presented using Microsoft Word and Excel (Tables).§ Mean Score Value (M.S.) =

Where: F = Frequency of response for each scoreS = Score given to each effectN = The total number of respondents for each factor

Where: F = Frequency of response for each scoreS = Score given to each effectN = The total number of respondents for each factor | Table 4.02. Mean score values (M) comparison table |

4.2.2. Qualitative Analysis (FGD)

- The researcher and assistant started managing the qualitative data collected in the field by taking field notes and recording audio during focus group discussions (FGD). The thematic approach was used to analyse the qualitative data, in–line with writings by [11] whereby, collected data were reported in–terms of themes or patterns. The collected data were transcribed, prepared, coded, and organised before being analyzed, in accordance with the writings by [12,18,89]. In the transcription and translation process, the data obtained in Kiswahili were translated into English by the researcher and cross–checked by an expert. Reading and re–reading the content, verifying and tallying the frequency of codes, noting some unique ideas that emerged from the data, and noting the relationships between variables and themes were all part of the coding process. Similar to a study by [18], the themes were centered on encapsulating the content's underlying meaning rather than being restricted to the precise words. Additionally, open–ended questions yielded views, opinions, comments, and concepts that were incorporated in the qualitative data analysis. Excerpts from the FGD were extracted and included to illustrate key findings.

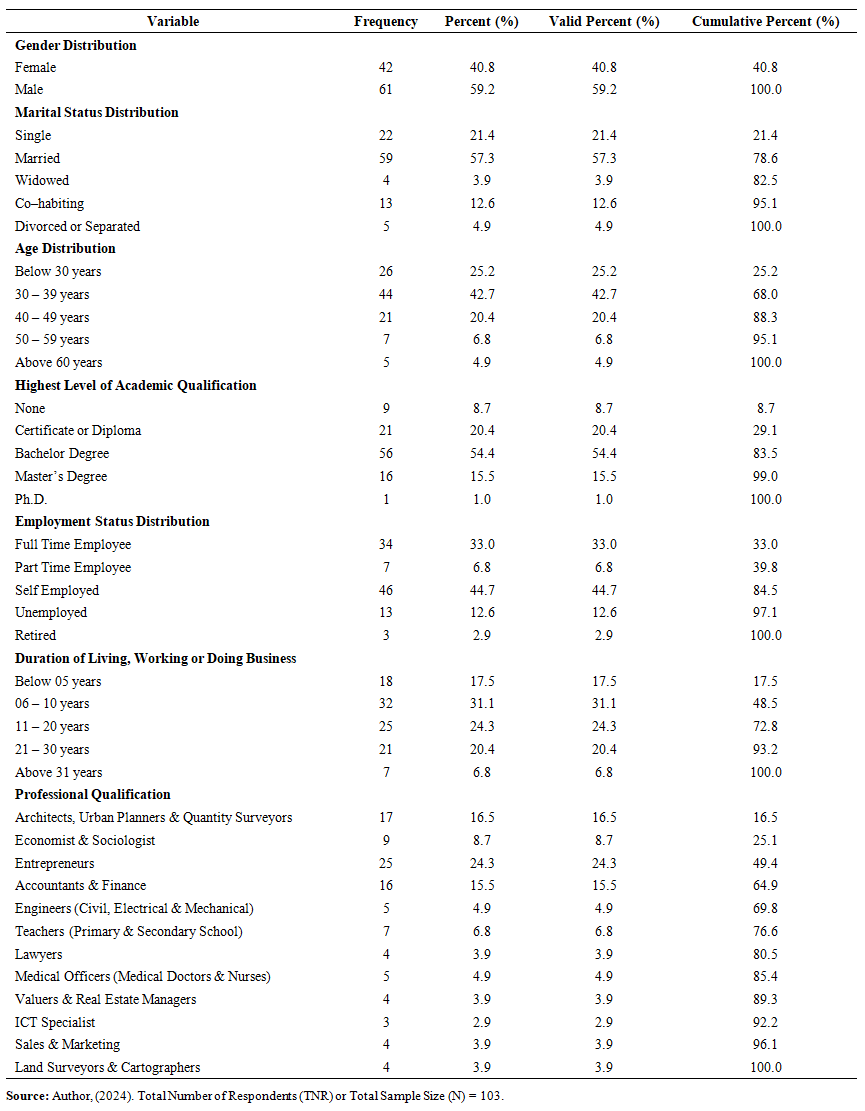

4.3. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

- This section is primarily intended to provide an overview of the demographic profiles derived from the questionnaires that were given to the respondents. The distribution of genders, marital status, age, highest level of education, employment status, length of time spent living, working, or conducting business, and professional qualifications are all summarised in Table 4.03.

| Table 4.03. the respondent’s demographic characteristics |

4.3.1. Gender Distribution

- As denoted in Table 4.03, the majority of the respondents (n = 61; 59.2%) were male, while 42 respondents, i.e. 40.8% were female. The male dominance reflects how improvisation of urban spaces in the areas is dominated by men, primarily because they serve as heads of the households and breadwinners, with a high likelihood of initiating, owning, operating and managing informal businesses. Basically, it is so because improvised urban spaces frequently offer economic opportunities with lower entry barriers, thus attracting more males who leverage these platforms for livelihood sustenance and household provision.

4.3.2. Marital Status Distribution

- Table 4.03 shows that; majority of the respondents (i.e., n = 59; 57.3%) were married; while 21.4% of the respondents i.e., n = 22, were single; 12.6% i.e., n = 13 respondents were co–habiting and living together as a family; 4.9% i.e., n = 5 respondents had undergone divorce or separated; and 3.9% i.e., n = 4 respondents were widows who had lost their spouse, from an undisclosed causes. This result shows that; improvisation of urban spaces creates adaptive environments for a number of household types, especially married and cohabiting couples who may rely on the proximity to livelihood options, and the safety, as well as more livable conditions offered by the adaptability of spaces. As highlighted by [52], informal urban settings often accommodate flexible family structures, which respond dynamically to the economic potentials and spatial arrangements afforded by such spaces.

4.3.3. Age Distribution

- Findings showed that; a substantial proportion of respondents i.e., 42.7% equivalent to n = 44 had an age between 30 to 39 years; 25.2% i.e., n = 26 respondents were below 30 years; while those between 40 to 49 years were 20.4% i.e., n = 21 respondents, and 6.8% i.e., n = 7 respondents had an age between 50 and 59 years. Only 4.9% i.e., n = 5, were respondents from an older age group, above 60 years. This age pattern illustrates that urban space improvisation mainly engages a youthful to middle–aged demographic, a group most likely to engage in spatial transformation and informal economic activities. Basically, the lack of employment opportunities forces them to rely on informal economies, by often acting and being at the forefront of creative uses of urban spaces by improvisation, e.g., by invading and turning urban spaces or abandoned lots into recreational or commercial areas. These findings are consistent with [76], which reports that youth and younger adults are at the forefront of informal urban space appropriation due to limited access to formal employment and housing.

4.3.4. Highest Level of Academic Qualification

- Out of 103 respondents, results revealed that 54.4% i.e., n = 56 respondents, had a Bachelor degree, 20.4% i.e., n = 21 respondents, had a certificate or diploma, and 15.5% i.e., n = 16 respondents, had a Master degree. While 8.7% i.e., n = 9 respondents had no any kind of formal academic qualification but rather a variety of informal qualifications. Only, 1.0% i.e., n = 01 respondent had a Ph.D., which was the highest level of academic qualification among respondents. With most of the respondents (n = 94; 91.2%) having sufficient academic qualifications implies that; most of the respondents' data collected were reliable. It also coincides with a report by [17] that; cities host the largest proportion of the population with higher education. Furthermore, the results indicate that; most of the improvised urban spaces are more occupied by the educated and skilled individuals than the uneducated, in creatively improvising and utilizing informally, urban spaces, as adaptive platforms for socio–economic activities and survival.

4.3.5. Employment Distribution

- From Table 4.03 results disclosed that; majority of the respondents (i.e., n = 46; 44.7%) were self–employed, owning and operating businesses, involved in a constellation of socio–economic activities (as seen in plates 4.01 to 4.36) on improvised urban spaces. Besides, 33.0% i.e., 34 respondents, were full time employees in public and private sectors; 12.6% i.e., n = 13 respondents, were unemployed; while 6.8% i.e., n = 7 respondents and 2.9% i.e., n = 3 respondents, were part–time employees and retired, respectively. These figures suggest that improvisation of urban spaces serves as an essential platform for self–employment and microenterprise development, especially where formal urban planning fails to provide adequate economic spaces (Roy, 2005).

4.3.6. Duration of Living, Working or Doing Business

- From an examination on Table 4.03, the results indicate that; 31.1% i.e., n = 32 respondents, had been living, working or doing business in the settlement for about 06 to 10 years. 24.3% i.e., n = 25 respondents been in the settlement for about 11 to 20 years, while 20.4% i.e., n = 21 respondents, had been there for about 21 to 30 years. Only 17.5% i.e., 18 respondents and 6.8% i.e., 7 respondents had been in the settlement for less that 5 years and for more than 31 years, respectively. Those who had lived in the settlement for more than 31 years were able to offer a very detailed experience on the evolution of urban space improvisation and the rapid change in the settlement’s physical form. Also, findings revealed that; 53% of the participants had been living, and/or working, and/or doing business in the settlement for more than 11 years and above, forming an attachment to the place resulted by, past activities and maintenance of continuity, i.e., proximity to education facilities, relatives, working areas, worshiping area, health facilities; density; number of customers; pedestrian flow; social networks; etc. In–line with [13,65,73], the lengthy in residence implies residents' and non–residents' physical attachment or “rootedness” to, and continuity with, the settlement. Additionally, [10] further argues that; the formation of attachment to place is connected with the daily feelings of continuity and emotional familiarity, suggesting that urban improvisation fosters not just economic utility but also emotional bonds and cultural rooting within evolving urban morphologies. Improvised urban spaces, though informal, become embedded in users' life histories and spatial consciousness.

4.3.7. Professional Qualification

- Relative to the professional qualification held by each respondent; the majority (i.e., n = 25; 24.3%) as seen in Table 4.03, were entrepreneurs involved in a constellation of socio–economic activities as seen in plate 4.01 to 4.36; 16.5% i.e., n = 17 participants were professionals in the built environment (architects, urban planners & quantity surveyors). While, 15.5% i.e., n = 16 respondents, 8.7% i.e., n = 9 respondents, and 6.8% i.e., 7 respondents were into accountants and finance professionally, economists and sociologists, and professional teachers teaching at primary and secondary school levels, respectively. Moreover, 4.9% i.e., n = 5 respondents each were engineers (civil, electrical & mechanical) and medical officers (medical doctors & nurses); 3.9% i.e., n = 4 respondent each were lawyers, valuers & real estate managers, sales & marketing, land surveyors & cartographer; and only 2.9% i.e., n = 3 were ICT specialist in–terms of hardware and software. The diversity in skills indicates that; improvised urban spaces are multifunctional and capable of supporting various professional activities beyond traditional informal trades. Such spaces offer platforms where expertise is translated into spatial practice, contributing to the self–organization and functionality of informal urban economies [2]. The result also shows that; skilled urbanites, technicians and professionals are involved in the informal sector, due to economic pressure, especially in cities like Dar–es–Salaam, with a high population size, and limited formal employment opportunities.

4.4. Effects of Urban Spaces Improvisation in the Planned Settlements

- A total of twenty–two (22) effects were identified and researched to reveal the impact from the improvisation of urban private and public spaces in the planned settlement, and the results were as follows: –

| Table 4.04. Presents the effects of improvisation on urban spaces in planned settlements |

| Table 4.05. Presents the results of a one–sample t-test on the effects of improvisation on urban spaces in the planned settlements |

| Figure 4.01. the settlement’s spatial integration of the road and street network, enhancing socio–economic activities, Source: Author, (2024) |

| Plate 02-11 |

5. Conclusions

- The study concludes that, out of twenty–two (22) effects resulted from improvisation of urban spaces in planned settlement, that were identified from an extensive literature review; (1) attaining daily livelihood and human basic needs; (2) an increase in social and economic diversity; (3) an increase in government revenue from property tax and commercial activities; and (4) an increase on the land value, were highly ranked effects. The least ranked effects were; (1) housing market segregation; (2) increase on non–communicable diseases (NCD's) (e.g., heart diseases, diabetes, lung diseases, strokes, etc.) due to lack of physical activities; (3) deterioration of the relationship between residents and urbanites fighting for the public spaces available; and (4) lack of safety and security. These effects were reliable with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.769. Likewise, the results of the one–sample t–test showed that; with the exception of eight (08) (out of twenty–two (22)) identified effect, there was statistically significant difference, with p value less than 0.05 (i.e., p < 0.05), for the effects resulted by improvisation of urban spaces in a planned settlement. Besides, unbalanced land use patterns, decrease of outdoor space, inappropriate blockage of urban public spaces, pollution caused by uncollected solid wastes, and noise; etc., were added as effects resulted from the improvisation of urban spaces in the planned settlement, by the respondents via an open–ended question. The study insists on awareness creation to urbanites regarding adherence to urban planning regulatory frameworks, alongside assuming and taking on board all the positive effects, when reviewing urban planning policies, legislation (act), and standards, in order to deal with the negative effects. The same must be done before enacting the housing policy draft 04 of 2010, and the urban development and management policy (UDMP) (draft) of 2011. Also, a bottom–up approach must be embraced instead of the current top–bottom approach in any urban planning of a settlement, which shall also enhance community participation in urban planning.

Acknowledgements

- This paper is derived from the ongoing first author’s Ph.D. thesis, titled “Urban Space Improvisation: The Case of Planned Settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania”, supervised by the second and third authors, all from Ardhi University. It is an extension of an author’s already published paper titled “Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania; Its Existence and Causes”, extracted from the same Ph.D. thesis, as detailed in this paper’s references. The University made this study possible through its continuous support, facilitated by a Scholarship from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST) of the United Republic of Tanzania.

Disclosure Statement

- The authors declared no potential competing conflicts of interest.

Participation Consent

- During this study, all respondents were provided with a written consent form outlining the nature and purpose of the research survey.

APPENDIX – (01)

- A part of a research questionnaire used, on; – effects from urban space improvisation in the planned settlements?1. What do you think are the effects from the improvisation of urban private and public spaces in the planned settlement? (Strongly Agree (SA) = 5, Agree (A) = 4, Moderate (M) = 3, Disagree (SD) = 2, Strongly Disagree (D) = 1).

What are other effects from the improvisation of urban spaces emerging in the planned settlement, that you know of?

What are other effects from the improvisation of urban spaces emerging in the planned settlement, that you know of? 1. Urban Planning and Space Standards; includes standards for plot size or density, skylines, building lines and setbacks, plot coverage and plot ratio, health and education facilities, golf courses, passive and active recreation, public facilities by planning levels, public facilities by population size, parking, residential areas and agricultural show grounds, standard for electric supply and its way leave for water supply, road width, communication pylons, sewerage treatment plants, ponds, transportation terminals, stream or rivers valley buffer zone, beaches and industrial plots and recommended colors for land uses [81–82].

1. Urban Planning and Space Standards; includes standards for plot size or density, skylines, building lines and setbacks, plot coverage and plot ratio, health and education facilities, golf courses, passive and active recreation, public facilities by planning levels, public facilities by population size, parking, residential areas and agricultural show grounds, standard for electric supply and its way leave for water supply, road width, communication pylons, sewerage treatment plants, ponds, transportation terminals, stream or rivers valley buffer zone, beaches and industrial plots and recommended colors for land uses [81–82]. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML