-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2025; 15(1): 1-31

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20251501.01

Received: May 9, 2025; Accepted: Jun. 3, 2025; Published: Oct. 15, 2025.

Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania; Its Existence and Causes

Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, Shubira L. Kalugila, Daniel A. Mbisso, Valentine G.M. Luvara

ARDHI University (ARU), Dar–Es–Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania

Correspondence to: Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, ARDHI University (ARU), Dar–Es–Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Cities in most developing countries have been, and continue to experience rapid population growth, alongside an influx of informal socio–economic activities hosted informally on planned urban spaces. The accommodation of most of these activities by urbanites, is done by improvising planned urban spaces. Thus, in pursuit of understanding their existence and causes driving urbanites to improvise urban spaces in planned settlements, in Dar–Es–salaam, Tanzania; this paper explores and analyses the issue. It employed a sequential explanatory mixed–methods approach, primarily using quantitative methods, supplemented by qualitative techniques, with multiple data collection tools, i.e., questionnaires, observations, interviews, photographic registrations and FGD. Likewise, it also employed a descriptive case study strategy, focusing on Sinza “A” in Dar–Es–Salaam. A total of 110 questionnaires were distributed via stratified random sampling to building owners, tenants, and officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs with 106 (i.e., 96.4%) properly filled and returned. The collected data were cleaned, coded, processed, in which the quantitative data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics (one–sample t–test). This paper revealed the existence of improvised urban spaces by urbanites, within the planned settlement, engaged in a list of socio–economic activities. Moreover, the addition of space due to demand or lack of space for rental purposes, commercial activities, housing etc.; unemployment, poverty, and the informal sector’s need for space; were among of the highly ranked causes. Other findings from open–ended question, revealed more causes i.e.; weak adherence to existing urban policies, legislations (acts) and regulations, etc. The paper concludes and recommends on; eliminating overlaps between CGA and LGA powers; reviewing and enacting existing regulatory frameworks; allocating sufficient resources to CGA and LGA to reduce bureaucracy and double allocation; providing training up to the Mtaa level; leasing some public spaces for community activities and land banking; and involving people early in urban planning through a bottom–up approach.

Keywords: Causes, Urban Space, Improvisation, Socio–economic Activities, Planned Settlements, Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania

Cite this paper: Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, Shubira L. Kalugila, Daniel A. Mbisso, Valentine G.M. Luvara, Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania; Its Existence and Causes, Architecture Research, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-31. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20251501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cities are experiencing rapid population growth, accompanied by an increasing influx of informal socio–economic activities hosted informally on improvised planned urban space, within a planned settlement. The influx is triggered by the inherent multifunctionality of urban spaces in cities, which acts as platforms for social interaction where people meet to exchange ideas, economic opportunities, trading, leisure and relaxation [29]. However, the growth patterns and impacts of such improvisation, differs from one city to another depending on the nature of the; population, existing planning and spatial policies, legislation (acts) and standards; as well as the nature of socio–economic activities undertaken within individual settlements. Moreover, the difference is also resulted from the fact that, the characteristics of urban spaces originally shaped by top–down planning mechanism, are increasingly being re–created by changes, through everyday practices and informal adjustments made to accommodate the socio–economic activities. According to [123], these improvised changes are taking place very fast, reflecting the real resident’s socio–economic needs, hence fuelling major structural shifts and diverging from the original design as well as function envisioned in formal urban plans. Also, these changes, are caused by several reasons, in a struggle to host various socio–economic activities, undertaken by urbanites through urban space improvisation, which vary depending on the settlement’s nature and locality. The variation on urban space improvisation is because; every city and settlement as per [121] is unique, and differs from all others i.e., no two cities or settlements can be alike. As a result, each planned settlement within a city begins to evolve with its own distinct narrative, characterized by factors such as accessibility, walkability, legibility, robustness, safety, and spatial texture, driven by its improvised use [70,123].Likewise, this spontaneous reconfiguration of space, prompted by shifting socio–economic pressures, that leads to rapid and uneven transformations of both public and private urban areas. These spaces are increasingly threatened by overlapping demands, causing friction between formal urban design intentions and informal practices [69,70]. Improvised use becomes a response mechanism; an adaptive strategy to accommodate socio–economic functions where formal space provision is either absent or inadequate. As [121] highlight, every city and settlement is inherently unique, thereby rendering improvisation patterns equally diverse across contexts. All these socio–economic activities, are carried on urban spaces which are a fundamental element of successful cities, with their role in economically as per [69,121] being evident in shaping the city, their urban patterns, the order of their physical elements, their meanings, and its support for human activities, leisure and retail activities, which drive the urban economy in many cities. All these alongside with the on–going on urban space improvisation, makes it impossible for the LGA officials to achieve an orderly city, given the incoming informal socio–economic activities, as a result matching writing by [22] that; on the quest of achieving a utopian kind of environment where all appears orderly and in place, it is futile to plan a city’s appearance or speculate on how to endow it with a pleasing appearance or order, without knowing what is the basis that initially helps it function, and what sort of order it has, that can be incorporated in the initial urban design considerations. The impossibility is fuelled by its “help–yourself” mode of spatial practice, [28], and notion of urban space being a site of both contestation and opportunity, where spatial transitions emerge from unplanned, and often unregulated practices. Also, the situation has been and continues to get more serious in which urban spaces have been increasingly improvised, through unregulated practices which birth alternative forms of spatial organization [20,53], manifesting as informal, guerrilla, insurgent, do–it–yourself, or tactical urbanism [28]. This is evidenced by a paradigm by [105] which portrays the everyday urban life as both inventive, insecure, and often pulled by particular cadences of creativity and resilience, in–term of spatial use. Basically, at its core; improvisation is a creative problem–solving process, and a means by which people can generate original and useful practical solutions [26], in responses on the lack and need for vacant urban spaces, that can host socio–economic activities. In reality, settlement or neighbourhood may be either planned or unplanned. Although improvised socio–economic activities are habitually hosted in informal settlements, but they have penetrated and found their way into planned settlements, reflecting broader failures in spatial provisioning and the growing mismatch between planned space, lived realities, and a need for spaces that can host these activities. Essentially, by 2018; more than half of the world population (i.e., 4.2 billion or 55%) lived in cities, and the figure is expected to raise to 6 billion or 66%, by the middle of this century (i.e., 2041), [54,60,88,98,111,113]. By 2050, world’s population is expected to raise to 9 billion from 7 billion in 2012, [68,108], which will also see the global urban population increasing from 3 billion to 6.7. billion, corresponding to 69% of the world population [54,81,111]. This population influx into cities, is resulted by a search for the unexpected and unforeseen, due to cities being the primary centres of a number of economic opportunities and livelihood opportunities [53]. [20,41]. This results into escalating pressure on the available scanty urban space and infrastructure, intensifying improvisation on previously well planned and regulated urban areas [65,133]. It also re–shape how the next generations, shall to re–imagine, re–design, re–work urban, and manage urban spaces, because; planned settlements once thought immune to informal transformations, are now improvised and their original planned functionality as well as spatial meaning, changed and overlaid with emergent practices by urbanites, out of necessity, creating a hybrid landscape.Furthermore, this challenge is also acknowledged by the global development framework, by introducing and adopting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (2015 – 2030), preceded by Millennium Development Goals (MDG) (2000 – 2015). Technically, the SDGs, specifically Goal 11; aims by 2030 on making cities and human settlement inclusive, affordable, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Its key targets include; access to adequate housing (11.1), sustainable transport systems (11.2), participatory urban planning (11.3), reducing the impact on environment (11.6), and ensuring universal access to safe public spaces (11.7). All these targets, goes hand–in–hand by being supported with; SDG goal number 1, on ending poverty and goal number 8 on decent work and economic growth for all, all of which everywhere, and ensuring equal rights to economic resources as well as access to basic services; and SDG 8, promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all. All these goals recognize the vital role of public space in supporting socio–economic resilience [19,78,110–112]. Again, it was also acknowledged and raised during the Habitat III Conference (Quito 2016), which emphasized the need for clear spatial standards, recommending 50% of urban land to be allocated to streets and public spaces, broken down into 30% for streets and sidewalks, and 15% to 20% for open spaces, green spaces and public facilities [110]. However, many cities, particularly in Southern regions, are far from this target in order to achieve well–coordinated, inclusive, and spatially efficient urban environments. The gap is caused by the targets often clashing with lived urban realities, where improvisation persists as a spatial survival strategy.Likewise, in the Sub–Saharan Africa (SSA), this gap arises due to persistent informality, rapid urbanization, high population growth, unemployment, and mismatching between urban planning and actual development realities. As a result, it also continues to transform and re–shape urban landscapes physically, economically, and environmentally [60]. This transformation is particularly intense, with SSA hosting some of the world's fastest–growing cities [78]. Together with Asia, the region accounts for over 90% of the global urban population growth [124], thus significantly influencing urban form and function [65]. It is said that; the urban populations in SSA are growing at an estimated annual rate of 4% [67], and it is projected to rise from 400 million in 2010 to 1.339 billion by 2050, corresponding to 21% of the world’s projected urban population [88,111,113]. [67], further highlight that; SSA cities are home to a lion share of the urban population living in poverty, and the share is projected to reach 50% by 2035, and almost 58% by 2050. This intensifying urban concentration in SSA cities is accompanied by increasing demand for goods, services, and physical space, as well as high levels of interactions, ample opportunities for wealth creation, resource distribution, which often outpace formal planning mechanisms. As noted by [55], over 80% of global economic activities occur in urban areas, many of which unfold on improvised or informally adapted urban spaces. The absence of adequate planning responses has led to a proliferation of these informal adaptations, commonly referred to as urban space improvisation. In dealing with this challenge, the SSA countries, has also adopted policy frameworks called the African Union’s Agenda 2063, on “the Africa we want”, which aspires to a prosperous and inclusive Africa. This agenda emphasizes poverty eradication through inclusive and diversified socio–economic transformation, aiming to uplift citizens’ quality of life, standard of living, sound health and well–being. However, as [5] highlights, many African urban planning systems fail to incorporate the aspirations, capacities, and survival strategies of urban residents, living within African cities, leaving them with no option other than turning to informal activities operated on improvised urban spaces, outside the formal system.Tanzania, a rapidly urbanizing country in SSA, illustrates this phenomenon clearly. Its cities have emerged as country’s engines for economic hubs, [34,81], with urban population share increasing from 5.7% in 1967 to 29.1% by 2012. Projections indicate this figure will surpass 50% by [34], driven by Tanzania’s overall population growth from 12 million in 1967 to 61.7 million in 2022, projected to increase to 68.6 million by 2050 [81,85,124]. This country’s rapid urban growth rate is reflected by the increase in socio–economic activities outpacing the formal spatial capacity [8]. In dealing with the circumstances, Tanzania outlined long–term development goals under Vision 2025, followed by long–term development Vision 2050, both targeting at building a resilient and inclusive economy capable of competing globally, as well as enhancing the quality of life for all citizens, [116,120]. These long–term plans recognize the importance of socio–economic activities both formal and informal, aiming at promoting socio–economic growth, and integrating the targets into broader economic and spatial planning frameworks. However, challenges related to urban space improvisation remain unresolved. As the nation transitions toward Vision 2050, addressing these challenges by knowing the causes, will be critical to achieving sustainable urbanization goals. These aspirations require effective land use planning, and balanced urban growth. Moving forward, Tanzania also has had three (03), Five–Year Development Plans (FYDP), i.e., FYDP I (2011–2016), FYDP II (2016–2021), and the current one FYDP III (2021–2026), conceived to implement the Tanzania Development Vision 2025, addressing issues related to; employment creation, poverty reduction and eradication, formalization of the informal economy, housing, human settlements, land management, etc.One of its cities involved in all the planning mentioned above is Dar–es–Salaam, which is globally ranked at 49 among the top 600 cities with a fifth of the world’s population, having more than 6.5 million population. Principally, it is one among many cities in SSA that have been and continues to rapidly grow, attracting the majority of migrants, while experiencing rapid urbanization [7,98,104], alongside being projected to obtain megacity status by 2034, [81,98,113]. In SSA, it is also together with cities like Johannesburg, Khartoum, Casablanca, projected to reach a population of ten (10) million inhabitants, by 2030, [81,88]. This rapid population growth is coupled with the city urbanizing under poverty, intensively strains urban spatial use, alongside highlighting the incapacity of local governments (LGAs) in managing spatial use effectively, hence giving rise to urban space improvisation, and an intriguing question on how does improvisation emerge. Again, [109], argues that; effective improvisation in urban contexts requires flexible system, that allows for bottom–up planning approaches that are responsive to local realities rather than rigid, top–down impositions. For it to be adopted in any urban space planning system, one must understand, the causes behind urban space improvisation. This is also of paramount importance due to urban spaces intrusion by people who have been squatting on public spaces or land (i.e., road reserves, railway lines, forests and public open spaces as well as utilities) putting on semi–permanent and temporary structures as highlighted by [66] in order to conduct the socio–economic activities, in planned settlements. The invasion caused by the lack of specific planned urban spaces that can temporarily or semi–permanently accommodate the conducted socio–economic activities, triggered by what [26] specified as lack or inadequacy of detailed plans that can accommodate such activities, hence leading people to improvise planned urban spaces.Most arguments on informalization of settlements, are pegged and weighed with the planning and space standards regulations1 in the planned settlements, by most researchers, academician, and even planners, whom in most aspects, considers these planning and space standards regulations in the planned settlements, as a mirror. The city planned using these planning and space standards regulation, is considered as “a clean city planning model”. This model is expected to develop and deliver a well–planned city, but unfortunately it is not the case when we look at the cities in developing countries, where most of them develops informally as an extension of the planned settlements. This informalization has also leapfrogged into these planned settlements via urban space improvisation. Hence, the need on analysing the causes of urban space improvisation, as the study identifies a gap in knowledge as per [106] basing on the fact that; a number of studies on transformation, its qualities, space production and use in unplanned settlements in Dar–es–Salaam, Tanzania, have been carried out. This is further evidenced from the studies by; [5,44,45,51,64,68,77,80,85,87]. But apart from a study by [50] which reports on mismatch between what is planned for, and what happens, and another one [95], on informalization of planned settlements via improvising planned spaces; scant information exists in the context of Tanzania, on; the cause of urban space improvisation, in planned settlements. Hence, the study extends further from [95], using different study location, sample type, sample size, methodology, and analytical angle, in order to fill the gap, alongside informing conventional urban planning and design as well as policy formulation for sustainable development. It aims at analysing the causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlements in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania.

2. Urban Space Improvisation in Planned Settlements

2.1. Space

- Space as per [75] can simply be defined as “an amount of an area or of a place that is empty or available for use; i.e., the whole area in which all things exist and move”. It is an area or place or a totality system of the public realm where people or individuals with multiple political, cultural and socio–economic background or status, can access, interacts, exchange and conduct their daily political, cultural and socio–economic activities, with each other and their surroundings in the urban context, [11,90]. Moreover, [6] proclaims that; space can also be defined as a place limited by void that surrounds us, and it contains different scales; i.e., a room, a house, a street, squares, parks and gardens, playgrounds, neighbourhood, settlements, quarter, city, country and even the rest of the world. According to [28,92], space is amorphous and intangible, however we can feel it, know it, explain it, and can be sliced up to be improvised and used informally to host various socio–economic activities in which some may degrade or upgrade its status and value. The slicing is possible because every space can have one or more functions either in–terms of occupation or with regard to movement [121].

2.2. Improvisation

- Improvisation, being the key feature of cities as per [84]. Its word originates from Latin word “improvisus”, which means “the unforeseen” [33,84,122], without or absence of a provision [52,53], or unpredictable, as per [72]. It is a process or an ability to create and implement something or a series of unplanned activities or solutions, that have not been agreed on, or planned or stipulation made beforehand; hence ending–up presenting themselves as unforeseen and unexpected [52,53,72]. Moreover, it is the provision of alternatives to all things, which can be in the form of an addition, an adaptation, a change etc., in response to unanticipated situations that are outside the prepared institutional and regulatory boundaries [52,109]. Improvisation is practiced in a variety of domains, including music, dance, and theatre [53] as well as architecture and urban planning. [53,102] details that; improvisation apart from being a process which is always misunderstood, it is a relatively an understudied aspect of creativity and cognition that offers a kind of disorder (e.g., informal use of planned urban spaces), which can benefit city life. A common interpretation is that/ when something is improvised, it is to make up for the lack of something, or to get by in some way until the plan that was lost, can be recovered [53]. Additionally, [53] highlights that; improvisation has to do with how people take shortcuts between the formal paths, whereby it may not be preceded by a plan, but by past experience and processes of preparation. He adds that; it is a subversive nature of acting in the moment, by which users reappropriate space organized by powerful strategies and techniques of socio–cultural production. According to [52,53], in a controlled framework, improvisation is expressed clearly as a spontaneous intervention, and a process characterised by a simultaneity of conception and execution or action. [26] stress that; improvisation, by its nature, occurs at the intersection of action and cognition.

2.3. Space Improvisation or Improvisation of Space

- In this study, “space improvisation” stands for an act and the process fuelled by residents in the planned neighbourhood, who illegally invade, move into, spontaneously subdivide and use various planned urban spaces for different unplanned socio–economic, cultural and political spatial needs or activities, just to take shortcut from the formal institutional and regulatory system, in order to cater for the lack of urban space, and meet their daily basic needs. Moreover, [121] asserts that; whether major or minor, improvisation involves the embellishment of something, and for this study, it is the embellishment of urban spaces in planned settlements which is paid attention to. Hence, space improvisation as per [20] involves form of organizing spaces in order to host activities that are not considered by the planning discipline. [84] detail that; improvisation works with what is available, whether it is caused by a less–than–concrete city plan, a half–functioning planning policy, legislations (acts) and standards, a nasty yet dominant moral code, or an infrastructure that no longer meets people’s needs.According to [33] space improvisation often takes place in settlements, and it is understood as an intuitive, spontaneous and responsive activity, that offers spaces which accommodate activities that the planning scheme, fails to offer. Meaning that, from conception or planning and execution, action collapses into a single moment in–terms of time and space; i.e., they happen simultaneously, with no actual or specific plan for a space to be used on that moment, but rather motivated by lack or absence of plan [53]. It has to do with, “making the most from an original planned space, by informally adding more use to it, in order to get the most out of it”, outside state control, and beyond the existing institutional as well as regulatory framework. Simply, it has to do with the informal production of urban spaces in planned settlements. Improvisation allows for a shift from mono–function to multi–function use of urban spaces, while managing the limited available resources, alongside allowing things to continue in a difficult condition [61].

2.4. Space Improvisation in Urban Cities

- According to [53], improvisation and the city, have been intertwined throughout the history. With the city being a product of everyday practises [20], i.e., what its residents actually make of it every day [53], and if we see it as in a permanent tension between the built, fixed and rigid on the one hand, and engines of creation, loci of crises, sites of the surprising and unexpected on the other [3], then improvisation is never far [84]. It is so because, via space improvisation; cities can transform over time, and change from its original form, with the key actors actively involved in the shaping process being its people, governed by a number of planning policies, legislation (acts) and regulations. In most cases, the space improvisation changes the form of city formally as well as informally, creating planned and unplanned settlements. It may also change the form of the planned settlements, informally. The city form changes formally, as a result of employing the existing urban planning legislations (acts), standards and the spoken Urban Design Dimensions (UDD), which as per [10,11], includes; Morphological, Perceptual, Social, Visual, Temporal and Functional Dimension.What is not spoken, is when the city spaces are improvised changing the city form informally, with or without employing planning legislations (acts), standards and UDD. On finding out what causes the city form to change informally via improvisation; the spoken UDD, can be used to verify and find out; the existence and what really leads into urban space improvisation. From these spoken UDD, it can be clearly understood that; urban design deals with a rapidly changing environment, driven by diverse user and activities, while involving diverse transition processes. Thus, it is necessary to see urban design as both design process and product, [10,11]. Basically, most of urban space improvisation is not planned nor designed, and these has led to informal spaces becoming the predominant urban form, hence enlightening the importance of not ignoring the contribution of billions of people who are shaping our cities outside the domain of certified planners and architects. These informal practices of design compel us to rethink urban design from a non–traditional perspective. Generally, as per [10]; there are essentially two types of urban spaces systems, i) where building defines spaces, example a building at the centre with a front and real garden, or a building in a block with a courtyard at the centre, surrounded by a transition of carronades, pedestrians and access roads, in the perimeter ii) where building are objects in spaces. But when looking at the aerial view of the Dar–es–Salaam city today, neither buildings defining spaces, nor building as objects in space, are seen. The situation rises a question that; “maybe, there is a third unknown level of scenario which needs to be known and understood”, due to the city growing contrary to the theories laid down by [10]. Moreover, in the city form and layout, there are parts which do not change, or change slowly and the part which changes over a much shorter period of time, [11]. Surprisingly, all what is seen in Dar–es–Salaam city, belong to group one, where most of the spaces in the city are packed by permanent and fixed elements, which do not change at all. If this situation continues, it may displace other UDD, remaining only with morphological, hence calling for an investigation, on the craving of the morphological city only. Being morphological only, means the possibility on a displacement of; perceptual dimension including the imageability of the city, in–terms of referencing; the city as a living room (social dimension), a city as a dynamic theme (temporal dimension), and the city a machine to live in (functional dimension).Furthermore, the scenario is even more shocking, when looking at the axonometric glimpse of the city’s google map, due to its cacophony caused by the lack of; (a) clear urban fabric2, (b) pattern of space or buildings, and (c) clarity of private and public space. This depiction, rises a number of questions, including; what causes such kind of setting?, Also, as per [48], the concern with the inappropriateness of the regulatory framework has been expressed since the 1980s, in which a study by Okpala, (1987) blamed the administrators of land delivery and management for perpetuating concepts and standards received from the colonial era, although these are increasingly inappropriate to the situation to which they are being applied. Quoting [48] exemplify by pointing out that; official housing standards adopted in African cities are largely elitist, unrelated to social and economic realities, imitative of European or North American standards, indifferent to local experience and irrelevant to local culture. They also lack reference to the local economy and are virtually impossible to enforce. All these leads into the regulatory framework being seen as too bureaucratic, unrealistic, and unnecessarily increasing the cost of access to legal spaces and shelter especially for poor households, and fostering a climate for improvisation. Additionally, from the google map, the finger type city form is clearly seen to contain planned and unplanned settlements. In order to understand space improvisation in planned settlement within the urban areas; questions such as how was it at the beginning?, how is it now dimensionally?, what causes such circumstances?, etc. cannot be avoided. Given the numerical proliferation of urban space improvisation in the urban planned settlements, these questions can create knowledge on why the residents, have been able to create and extend informally, and still survive for so long, without following properly the urban planning legislations (acts), standards, and development guidelines. It is from this angle, that unspoken UDDs, may be revealed.

2.5. Causes of Space Improvisation in the Planned Settlement

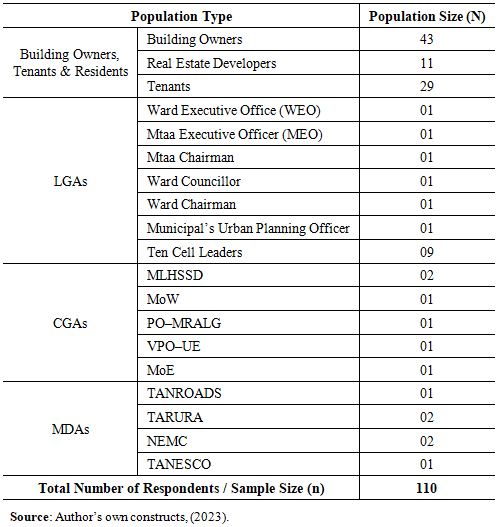

- The use of urban spaces in planned settlement, that are improvised and used informally hosting numerous activities, can be resulted from a number of political, cultural and socio–economic factors, as detailed in the Table 2.01 below; –

| Table 2.01. The causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlement |

2.6. Socio–Economic Activities

- Fundamentally, social activities involve interactions, connections and coming into contacts and meeting different residents and non–residents, whereby it could be during participating in community activities, religious or cultural ceremonies like; funeral, weddings, sports events, works, etc. Meanwhile, economic activities involve activities related to production, purchasing (i.e., buying), exchange, or selling different services and products or commodities, like; vegetables and food products from agricultural activities; clothes from the tailoring activities, and boutiques or fabric sellers. Others include, stationeries; food and drinks from fast–food restaurants, bars, and pubs; products from shop keeping activities; different kind of meets from animal grazing activities; building hardware materials and steel for construction activities, furniture production, door and window burglar proofs or grills production; renting of room and houses; etc. Thus, a combination of social and economic activities is what is known as “socio–economic activities”. These two activities complement each other, (i.e., they go together). As a result, socio–economic activities, refers to all economically viable business and employment related activities, driven by existing social relations and activities, in order to attains human basic needs. Its factors include; income, education, employment, occupation, community safety, living conditions, family size and relationship, social support, etc. These socio–economic activities, can be undertaken formally or informally, within the urban spaces in a planned settlement. In this study, only informal socio–economic activities will be explored, due to their contribution on improvising urban spaces in planned areas. Moreover, within the context of planned urban settlement, they play a crucial role in the informal reconfiguration, repurposing, and re–appropriating planned spaces, designed with specific zoning and function intentions, in order to improvise, adapt and accommodate the socio–economic activities. Such improvisation may take the form of converting street corners into vending spots, transforming residential frontages into kiosks, or using public open spaces for gatherings and informal markets. These adaptations are not part of the original spatial design, but emerge organically as residents negotiate their daily survival and well–being through informal practices.

2.7. Urban Informality

- Urban informality is a multidimensional concept that cannot be accurately and/or thoroughly defined [40]. Despite countless struggles by [40,85], in defining the term; it’s the definition by [11,41] that captures what is related to this study. They generally define urban informality as a set of socio–economic activities or spatial practices, that operates outside the formal urban planning regulatory framework and state control. These informal activities are commonly carried out by marginalized urban groups, with limited working and economic capability, e.g., petty traders, street vendors, coolies and porters, small artisans, messengers, barbers, shoe–shines boys and personal servants, who make use of streets, alleys, and vacant lots to earn a living, while violating official urban planning zoning or regulatory standards. Importantly, informality is not only about legality, but also about access and adaptation. [85], link urban informality to inadequate legal and regulatory framework, ungovernable development practices, corrupt practices, bad governance in land delivery and spatial development processes, autonomy and creativity opening up development opportunities for those excluded, and survival practices of the poor. That is why; it is the centre of jobs and opportunities, which attracts population flows into the cities, due to its capacity enabling socio–economic activities, and interaction among different people, [40]. Writings by [11,32,41], indicates that; urban informality is not only integral to the functioning of many African cities but has become an integral and normalized part of the daily urban life, and a new way of life in cities, that comprises numerous aspects of daily socio–economic activities. It enables the provision of employment, affordable shelter, and social infrastructure that formal systems often fail to deliver. Urban space improvisation in planned settlements illustrates this reality, as residents find ways to circumvent planning constraints to secure livelihoods and overcome poverty. While in so doing [41], affirms that; urban informality arises with questions on right over public space, particularly on the capacity to get around and bypass urban planning legislations, standards as well as regulations, and transgress or break them. Basically, informality in–terms of informal use of urban space has led to conception of informal or unplanned settlements, that are quite different from formal or planned settlements as seen in plate 2.01, although serving the same purpose i.e., meeting the human basic needs. As it primarily occurs in unplanned settlements, urban informality has recently been quickly spreading into planned settlements, as well. This is confirmed by the on–going on urban space improvisation in planned settlement, which is a form of urban informality [41].

2.8. Unplanned and Planned Settlement

- Urban space improvisation in planned settlements is an emerging issue in urban studies, particularly in rapidly urbanizing cities like Dar–es–Salaam. Traditionally, the literature distinguishes between unplanned and planned settlements based on their definition, formation processes, typologically categories and locational existence, projection or growth, characteristics, regulatory frameworks, etc., [107]. But briefly, “unplanned settlements”, also known as informal settlements, or slums, or squatters, or low–income settlements, or unauthorized settlements, or uncontrolled settlements or semi–permanent settlements, or spontaneous settlements, as per [38,40,107], refers to partially or fully unauthorised housing settlements that are organically developed depending on the community’s socio–economic condition by those who can hardly access affordable housing through formal markets, and outside the formal urban planning regulatory framework. They accommodate a wide range of social and economic groups of people from low– middle– and high–income earners, (pre–dominantly the low–income earners) and are developed outside the formal system, without meeting a range of regulations relating to planning, land use, and health and safety. Meanwhile, planned settlements also known as formal settlements, refer to authorised housing settlements which from inception, are planned, and developed through formal processes, alongside being regulated by urban planning regulatory framework. Its overall development includes adequate infrastructures such as; access roads, storm water drainage system, electric supply, water supply, solid waste management systems, urban furniture, street lights, that in most cases are inadequate in unplanned settlements [39]. Generally, as far as a settlement being planned before being occupied by developers is concerned, planned settlements are contrary in most parts from unplanned settlements. However, the assumption that planned settlements are immune to informality is increasingly being challenged. As cities expand rapidly, even formally planned settlements are becoming sites of urban space improvisation, whereby residents in these areas often adapt, modify, and repurpose urban spaces to meet their spatial needs for conducting socio–economic activities, especially when the formal planning policy and regulatory framework fails to respond to growing population demands.Furthermore, in Tanzania, specifically Dar–es–Salaam were the study conducted; the scale of urbanization has intensified both the proliferation of unplanned settlements and informal activities within planned areas. The number of informal settlements has tippled from 40 in 1985 to over 150 in 2003, and are expected to further increase, largely due to the city's economic centrality and status as Tanzania’s commercial and administrative hub hosting the largest seaport, as well as industrial, commercial and administrative activities, [39]. Also, their formation increase, is triggered by rapid urbanization growth experience by the city, i.e., a growth of 4.3% from 1998 to 2002, 5.6% from 2002 to 2012, and 4.5% in the period of 2015 to 2020, putting further pressure on both unplanned and planned settlements [39,107]. Furthermore, the rapid and uncontrolled urbanization growth, is often absorbed into unplanned settlements, which accommodates 70% and 80% of the Dar–es–Salaam city’s population, and 80% to 90% of urban residential housing stock as per [5,39,45,51,63,77,80,85,87,107,108]. This has made some unplanned settlements near the city centre, to end–up having densities of 300 or more persons per hectare [51], using the available urban spaces extensively, pushing urbanites into leapfrogging towards the planned settlements, in order to meet their daily spatial and basic needs.Basically, planned settlements, although formally established, are increasingly subject to informal practices via improving its existing planned spaces, through extending houses beyond designated architectural design and development controls, repurposing public or communal spaces for commercial use, and informally adjusting infrastructure. Such actions as said, they are forms of urban improvisation driven by necessity, revealing the failure of formal planning in anticipating the dynamic needs of urban populations. In some planned settlements, population densities now exceed 300 persons per hectare, mirroring the overcrowding typically associated with informal areas [51]. In most cases the planned settlement exists besides the unplanned settlements as seen in an aerial images or drone footage on plate 2.01. This convergence challenges the rigid dichotomy between planned and unplanned settlements, including spatial practices from unplanned often spilling into the other. The spillage is resulted from urban residents responding creatively to socio–economic pressures by modifying the planned urban fabric in ways that deviate from the original plans but make space more functional for daily living, [39,80,107,108]. Understanding this interplay is essential for developing more inclusive, adaptable, and responsive urban planning strategies in the face of ongoing urban improvisation challenges. This study, focuses on planned settlements, as shown above in an aerial images or drone footage on plate 2.01. The selection is based on the fact that; informality in planned settlements, is one of the recurrently raised themes in urban planning, that is rarely examined.

3. Methodology

- In–line with writings by [57,59,126], and for triangulation reasons, the methodology and research design employed in this study involved a sequential explanatory mixed–methods approach, in which apart from literature review; instruments like questionnaire, interview, and focus group discussion (FDG) were used by approaching various residents and non–residents in–terms of building owners, tenants, as well as government officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs. The unit of analysis based on urbanites utilizing urban spaces within Sinza “A” planned settlement in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania. The case study was employed because it can bring an understanding of a complex issue or object, and extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research, and it emphasize detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships, as also detailed in [36]. Likewise, in this study and basing on QUAN. and qual. strategy as per [73,103], meaning quantitative data was highly emphasized, with qualitative data providing a supplementary role to the quantitative findings, in–terms of assisting in explanations. This option made it easier in determining the intended objective, samples and design of the study, as well as ranking the causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlement. For the qualitative part of the study, the researcher was inspired by the grounded theory which aimed at understanding the processes behind urban space improvisation, experienced by each respondent, in order to refine the existing UDD theory. Also, as suggested by [21] the case study strategy was used due little or no prior information on urban space improvisation. A single case study approach was employed, despite [27] denoting how it is lowly regarded or simply ignored within the academy. Basically, it is ok to select a single case study, as per [17,93,127], because; it reveals more information alongside offering a much deeper investigation, than multiple case study, which dilutes the overall analysis. It offers an in–depth understanding on what causes a phenomenon, linking causes and outcomes; and it has high conceptual validity, [27]. Besides, [17] concretize that; the more cases an individual studies, the less the depth in any single case. Additionally, in most cases, a single case approach is selected due to its criticalness, extremeness, typicalness, revelatory power, or longitudinal possibility [127]. Again, a study by [27] observed that; “case studies” especially in social science, are likely to produce the best theory, because findings are generated using real life experiences and practices. Moreover, single case study approach was opted because; the most treasured classic knowledge, and much of what we know about the empirical world, were produced using the same methodology, [27]. He further exemplifies that; the most important knowledge generated by Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in Physics; Charles Darwin in Biology; Galilei Galileo on Law of Gravity; were all contributed from studies carried out using case study as one of the methodologies; hence underlining that; it is one and among critical and most useful methodology in research. And, its results from a single case study; can be generalized given the fact that knowledge is transferable. [93] concludes that; single case study is often used to understand extreme or unusual instances. Generally, Sinza “A” was selected as a case study area because it is unusual, extreme, and had enough information to present an in–depth detailed depiction, regarding urban space improvisation; hence offering an in–depth description and understanding of the studied issue, alongside expanding urban theories.

3.1. Data Collection Methods

- Generally, both primary and secondary data collection, were done using multiple data collection tools, were used as detailed by [57,59,71,126]. Questionnaire survey interviews, FGD, non–participatory or physical observations and photographic registration were used to collect primary data from the primary source (first hand) i.e., residents and non–residents in–terms of building owners, tenants living insides and outside the area, as well as government officials from LGAs (i.e., Municipal, WEO, and MEO), CGAs, and MDAs, in which the respondents answered the questions on their own. Some of the questions in the questionnaire were close ended and others were open ended to the respondent to attest their own opinion, and give in–depth information. Besides, secondary data on causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlement, were gathered from literature review via review of documentary reports, unpublished and published peer reviewed books, journals, articles and papers.

3.1.1. Questionnaire Design

- In this descriptive study, the employed and interactive self–completed survey questionnaire was prepared in accordance with research objective, and writing by [16,62,97,106]. The questionnaire, involved both close–ended and open–ended questions striving to uncover the causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlement, and it was divided into two (02) sections, which covered; – Section A requesting on respondent’s general demographic information; and Section B covering the existence and causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlements. The closed–ended questionnaire was developed based on the refined list mentioned earlier, following a pilot study. Closed–ended questions were chosen for their ease in gathering factual data and simplicity in analysis, as the possible responses are limited, [2]. Additionally, open–ended questions were included to gather more detailed feedback from respondents. The questionnaires were edited for completeness and consistency, checked for errors and omissions, as well as being filled completely. The pilot study was conducted to enhance the quality of the questionnaire and increase the reliability of the questions. It involved identified twenty–seven (27) causes of urban space improvisation Sinza “A”. The causes were all gauged on a five–point Likert scale, and by using [59] writings in scaling; the respondents were asked to respond to each statement, by indicating with which statement they do, Strongly Agree (SA) = 5, Agree (A) = 4, Moderate (M) = 3, Disagree (SD) = 2, or Strongly Disagree (D) = 1. Likewise, it also employed a descriptive case study strategy, focusing on Sinza “A” in Dar–Es–Salaam. A total of 110 questionnaires were distributed via stratified random sampling to building owners, tenants, and officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs with 106 (i.e., 96.4%) properly filled and returned. The collected data were cleaned, coded, processed, and later analysed by using IBM SPSS version 25, with an inner reliability for quantitative data tested using Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient in which the results must be above 0.70, guaranteeing an internal consistency of the information, which was a comparatively elevated internal consistency, suggests the scale is accurate. This is due to the fact highlighted by [73] that; the Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient value of greater than or equal to 0.70 is considered to be the minimum for an appropriate test, and any quantity less than 0.70 suggests bad reliability. Likewise, a one–sample t–test (μ = 3.5) was conducted to test causes that were statistically significant at a p < 0.05 for those with a Likert Scale of 5.

3.1.2. Interview

- The study, and in–line with writings by, [62,71,97,126], employed face to face semi–structured interview, with nine (09) key respondents who were given the opportunity to talk freely on the exitance and causes of urban space improvisation in planned settlements. Interview was opted for its flexibility in using unstandardized questions varying from interview to interview, allowing for in-depth exploration of urban space improvisation. Respondents were selected basing on their availability, contact easiness, experience, and willingness to participate. Interviews lasted between twenty–five (25) and forty (40) minutes, which aligns with recommendations by [73], who underlines that; for a reasonable interview, a duration of thirty (30) to sixty (60) minutes (i.e., one–hour) in any interview, suffices to be a reasonable interviewing time.

3.1.3. Focus Group Discussion (FGD)

- The FGD, basing on [31,62,71,97], was employed and conducted with thirteen (13) LGAs, residents and non–residents, selected using non–probability sampling, and FGD took approximately 45 minutes. The number coincides with [31,62,97], who highlights that; the optimal number of participants in a single FGD, is approximately between three (03) and twelve (12), and it should last not more than 90 minutes out of consideration for the participants' time, to capture robust information. During the FGD, the researcher as proposed by [73] moderated the discussion on the existence and causes of improvised urban spaces in the planned settlements, while being assisted by the research assistant who took notes and recorded the discussion. As insisted by [71,126], who warned of the risk of dominant participants; the researcher politely, tactfully, and in firm style, controlled and managed overtalkative individuals (e.g., by throwing kind jokes) to stimulate and encourage quieter participants without biasing the discussion. When the group became silent, gentle as well as kind words were used to reinitiate conversation without biasing its direction. Additionally, [31] adds that; one well conducted FGD, may be better than two or more, that are less effective.

3.1.4. Observations

- Basing on [62,71,97]; the non–participatory or physical observations was employed in this study in gathering the information required through; watching, listening, and record by documenting on–going on activities, behaviour, events, interactions, or physical characteristics in their natural occurring setting, without interviewing participants, so as to determine the existence and causes of urban space improvisation in Sinza “A”. The employed data collection method was achieved by assistance of the prepared observation guiding instrument which covered researched issues.

3.1.5. Photographic Registration & Sketches

- Photographs, sketches and maps in the study, were strategically taken and captured in order to document on the on–going on urban space improvisation, in various parts of Sinza “A”, and provide its trend. Besides, this data collection method was opted because, it is the appropriate tool that observation relies on, as per [126].

3.1.6. Review on Documentary Reports

- The study’s review on documentary report contributed for the secondary data, that had been collected previously, [15,73]. Basically, the review on various documentary reports in this study, based on; urban space improvisation, building typologies, space types, space use, policies, planning legislation and standards, etc. were reviewed.

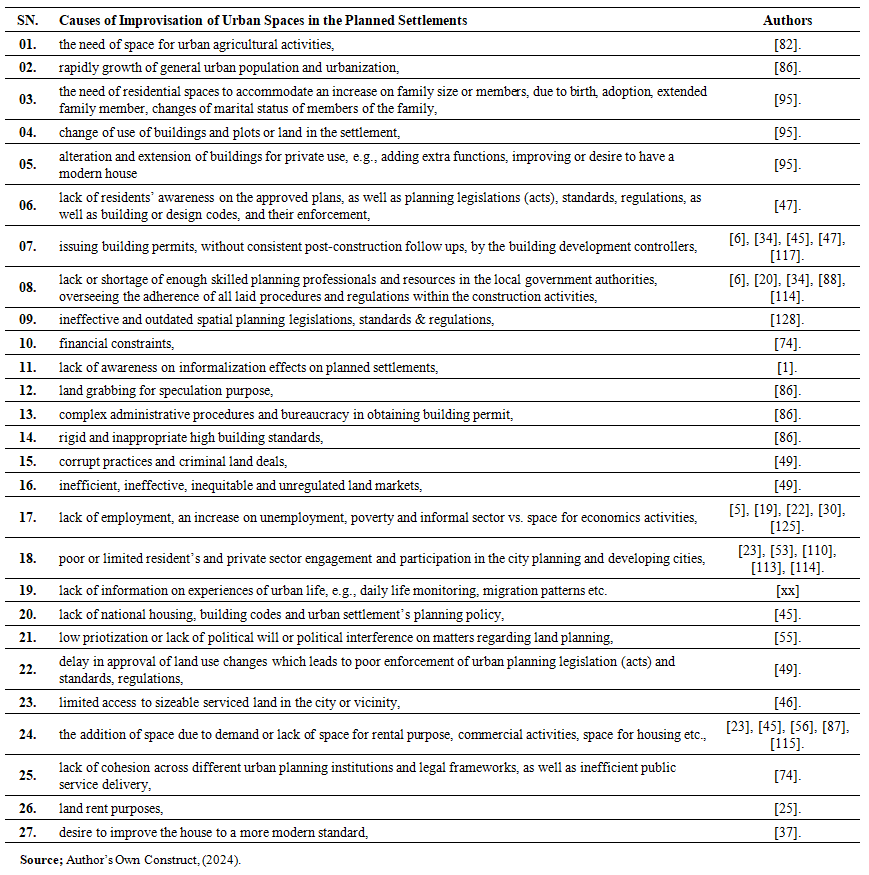

3.2. The Study Population and Sample Size

- The study sample population as highlighted by [57,62,106] that, it at least must have one thing in common or share similar characteristics that can be observed, identified and studied by the researcher, in order to generalize the results of the study; included residents and non–residents (i.e., building owners, tenants, real estate or property developer, living insides and outside the settlement), as well as government officials from LGAs, CGAs, and MDAs (i.e., ward counsellors, ward chairman, WEO, MEO, ten–cell leaders, municipal and ministerial official e.g., Town Planners, Engineers etc., officials from MDAs e.g., TARURA, NEMC, TANESCO, TANROADS, etc.), as shown in Table 3.01. As a result, and basing on the writings by [27,62,126] the study sample size was obtained using stratified random or probability sampling, in which respondents were divided into homogeneous subgroup (e.g., residents like building owners and tenants living in the areas; non–residents like business operators and tenants living outside the area; LGA officer from Municipal, WEO, MEO; CGA officer from Ministries and MDAs; etc.), and then randomly selected from each subgroup. Technically, the sampling selection aimed at (a) keeping the sampling error to a minimum, (b) avoiding systematic biases in the sample, and (c) the study’s intention on generalizing its findings numerically to the entire population of units, [27,126]. With the study unit of analysis being residents (i.e., residents e.g., building owners and tenants; WEO, MEO; and non–residents e.g., business operators; etc.) living and working in buildings within the case study area, as well as CGA officer from MDAs and LGA officer from Municipal. Thus, it was important to identify the sample size from the existing buildings, which represented a respondent from each selected existing building within the case study areas (Sinza “A”).

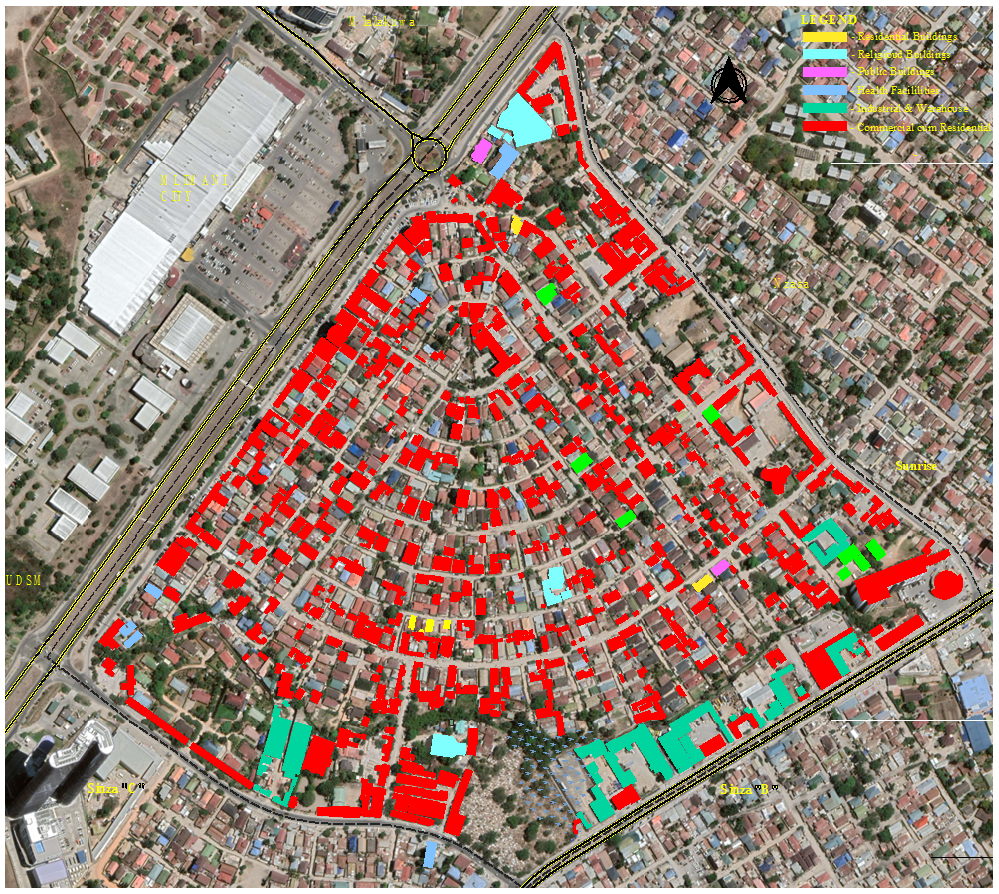

| Figure 3.01. The existing buildings within the case study area (i.e., Sinza “A”), Source: Fieldwork & Google Earth, (2023) |

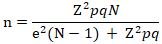

Where:n = the Sample SizeN = the Total Population Size i.e., = 1879Z = the Confidence Interval Level, i.e., = 95% (1.96)e = the Level of Precision or Margin of Sampling Error, i.e., = 5%p = the Degree Variability, i.e., = 50%q = 1 – p.As indicated above, the data used in sampling are confidence level (Z) – 95% (1.96) and level of precisions or margin of sampling error (e) – 5%. A study by [43] shows that; these values are economical to be used, and they have been used in various studies, including theirs. Essentially, the decrease in confidence interval level is equal to an increase in chance of error. Example, if the confidence interval level is 90%, it means the change of making errors is high i.e., 10%, than when the confidence interval level is 95%, due to the chance of making error being less, i.e., 5%. From the formula above, the calculated sample size (n) for the residents = 82.887 i.e., 83. The obtained residents sample size was then combined with the key respondent’s sample size to obtain the study’ total sample size (n) of 110, (as seen in Table 3.01).

Where:n = the Sample SizeN = the Total Population Size i.e., = 1879Z = the Confidence Interval Level, i.e., = 95% (1.96)e = the Level of Precision or Margin of Sampling Error, i.e., = 5%p = the Degree Variability, i.e., = 50%q = 1 – p.As indicated above, the data used in sampling are confidence level (Z) – 95% (1.96) and level of precisions or margin of sampling error (e) – 5%. A study by [43] shows that; these values are economical to be used, and they have been used in various studies, including theirs. Essentially, the decrease in confidence interval level is equal to an increase in chance of error. Example, if the confidence interval level is 90%, it means the change of making errors is high i.e., 10%, than when the confidence interval level is 95%, due to the chance of making error being less, i.e., 5%. From the formula above, the calculated sample size (n) for the residents = 82.887 i.e., 83. The obtained residents sample size was then combined with the key respondent’s sample size to obtain the study’ total sample size (n) of 110, (as seen in Table 3.01).4. Results, Analysis & Discussion

- The main issues covered in this study involved an exploration on the existence of improvised urban spaces in planned settlement, as well as analysing its causes.

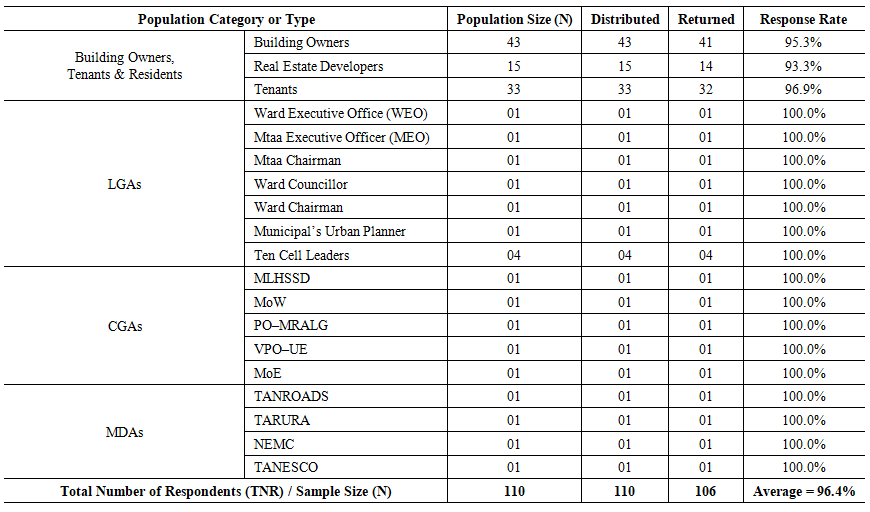

4.1. Survey Administration

- In this study, a structured questionnaire with five (05) Likert scale was applied to increase response rate and responses quality along with reducing respondent’s frustration level, [4]. A total of 110 questionnaires were distributed to targeted respondents, as seen in Table 4.01. Basically, only 106 i.e., 96.4% of the questionnaires were returned, in which 102 questionnaires were used for analysis, after four (04) questionnaires being left out, due to being not filled properly. The returned questionnaire had an acceptable response of 96.4% which concurs with writings by [83] on the fact that; the response rate of at least 50%, is statistically meaningful for analysis and publicity; a response rate of 60% is good, while a 70% response and above is outstanding. Similarly, [94,101] all portrays that; a response rate of at least 30% and above, is acceptable for any surveys. Moreover, [14,73], underlines that; the greater the response rate, the more representative of the target population, but if the response rate is low i.e., less than 50%, the study can be considered unacceptable, alongside generating validity issues.

| Table 4.01. The response for the questionnaires distributed to the respondents (building owners, tenants, officials from LGAs, CGAs, and officials from Ministerial Departmental Agencies (MDAs) |

4.2. Data Analysis

4.2.1. Quantitative Analysis (Questionnaire Survey)

- The collected data were cleaned, coded, processed, and later descriptively statistically analysed by using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25, in which mean score analysis, and standards deviation were calculated, hence ranking the causes in descending order, after being compared as seen in Table 4.02. It also involved, testing reliability for the quantitative data using Cronbach’s Alpha in which the results had a value above 0.70. A parametric test such as one–sample t–test (μ = 3.5) was conducted in order to measure the causes that were statistically significant at a p < 0.05 for those with a Likert Scale of 5, at a 95% confidence level, and μ being the test value. Also, the results were presented using Microsoft Word and Excel (Tables) in order to get more accurate computation that mapped out a pattern or relationship between measured or comparable variables.§ Mean Score Value (M.S.) =

Where: F = Frequency of response for each scoreS = Score given each causeN = The total number of respondents for each factor

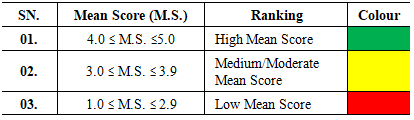

Where: F = Frequency of response for each scoreS = Score given each causeN = The total number of respondents for each factor | Table 4.02. Mean score values (M) comparison table |

4.2.2. Qualitative Analysis (Interview & FGD)

- The management of qualitative data obtained in the natural setting began in the field, whereby the researcher and assistant recorded all the unstructured interviews and FGD through field notes, and audio recording. The thematic approach was used to analyses the qualitative data, in–line with writings by [15] whereby, collected data were reported in–terms of themes or patterns. In–line with writing by [24,126], the collected data were transcribed, prepared, coded, organized, before being analysed. In the transcription and translation process; the data obtained in Kiswahili, were translated in English by the researcher and cross–checked by an expert from the Institute of Kiswahili Studies at University of Dar–es–Salaam, (UDSM). Coding was achieved by reading and re–reading the material, checking and counting frequency of codes; noting some original thoughts arising from the information; and noting relation among variables and themes. The themes, in the same way as highlighted in a study by [24], were not limited to the exact wording used but instead focused on capturing the underlying meaning of the content. Moreover, the analysis of qualitative data, included views, opinions, comments and concepts responded from open–ended questions. From this, the interview and FGD excerpts were extracted and included to illustrate key findings.

4.3. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

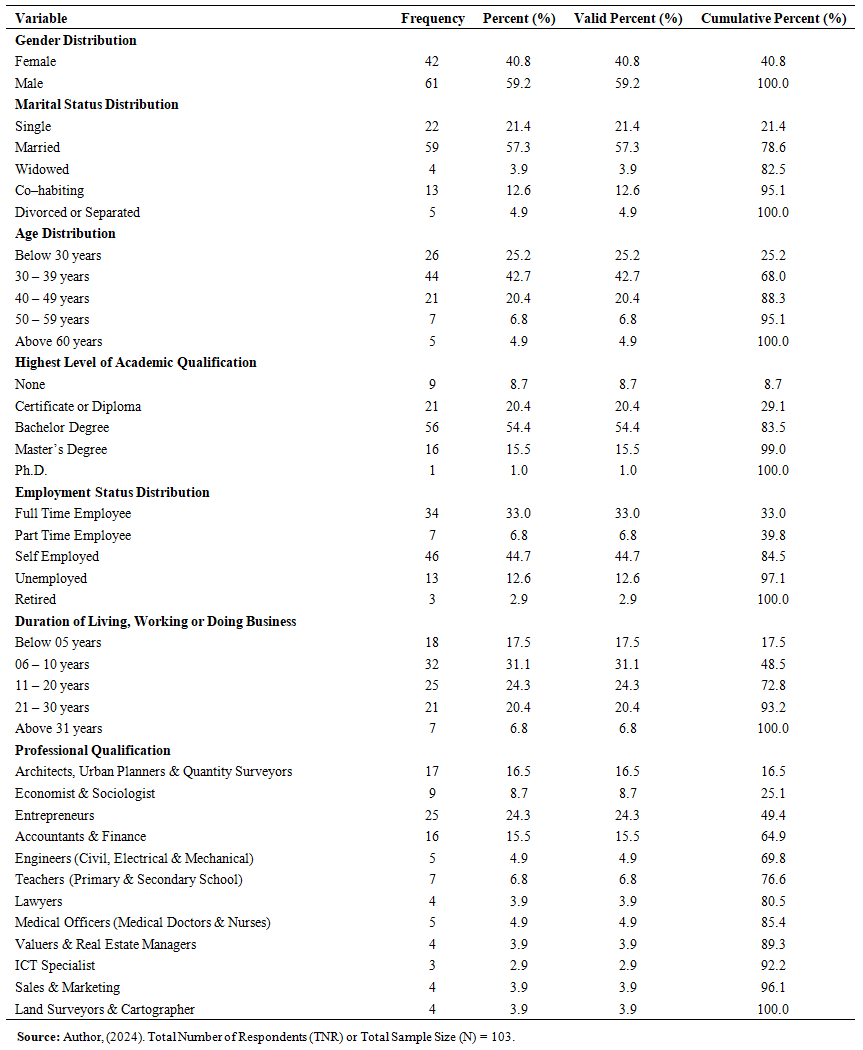

- This part mainly designed to summarizes demographic characteristics profiles, from the questionnaires distributed to respondents, and analysed in–terms of gender distribution; marital status distribution; age distribution; highest level of academic qualification; employment status distribution; duration of living, working or doing business; and professional qualification distribution; are summarized in Table 4.03.

| Table 4.03. The respondent’s demographic characteristics |

4.3.1. Gender Distribution

- As denoted in Table 4.03, majority of the respondents (n = 61; 59.2%) were male, while 42 respondents i.e. 40.8% were females. This gender imbalance reflects the male dominated ownership and leadership in informal urban economic activities, particularly those owned and operated on improvised urban spaces. This is due to the fact that; most men are heads of the households, alongside owning or operating micro–, medium–, and large businesses.

4.3.2. Marital Status Distribution

- Table 4.03 shows that; majority of the respondents (i.e., n = 59; 57.3%) were married; while 21.4% of the respondents i.e., n = 22, were single; 12.6% i.e., n = 13 respondents were co–habiting and living together as a family; 4.9% i.e., n = 5 respondents had undergone divorce or separated; and 3.9% i.e., n = 4 respondents were widows who had lost their spouse, from an undisclosed cause. With the majority being married, this indicates how a higher likelihood of several family demands, contributes to urban space improvisation in order to fulfill basic needs.

4.3.3. Age Distribution

- Findings showed that; a large proportion of respondents, i.e., 42.7% (n = 44) had an age between 30 to 39 years; followed by 25.2% i.e., n = 26 respondents who were below 30 years; while those between 40 to 49 years were 20.4% i.e., n = 21 respondents, and 6.8% i.e., n = 7 respondents had an age between 50 and 59 years. Only 4.9% i.e., n = 5 respondents were above 60 years. The age distribution reflects a predominantly active and economically productive population directly engaged in informally reshaping and utilizing urban spaces by improvising. Basically, the younger cohorts demonstrated more flexible and innovative approaches in improvising and using planned urban space, than the older cohort.

4.3.4. Highest Level of Academic Qualification

- Out of 103 respondents, results revealed that; 54.4% i.e., n = 56 respondents had a Bachelor degree, 20.4% i.e., n = 21 respondents had a certificate or diploma, and 15.5% i.e., n = 16 respondents had a Master degree. While 8.7% i.e., n = 9 respondents had no any kind of formal academic qualification but rather variety of informal qualification. Only, 1.0% i.e., n = 01 respondent had a Ph.D., which was the highest level of academic qualification among respondents. With most of the respondents (n = 94; 91.2%) having sufficient academic qualifications implies that; most of the respondents' data collected were, reliable. This high level of education among participants suggests a population capable of informed, strategic improvisation of urban spaces. Their presence enhances the potential for creative, sustainable, and community driven spatial adaptation. It also coincides with a report by [23] that; cities host the largest proportion of the population with higher education.

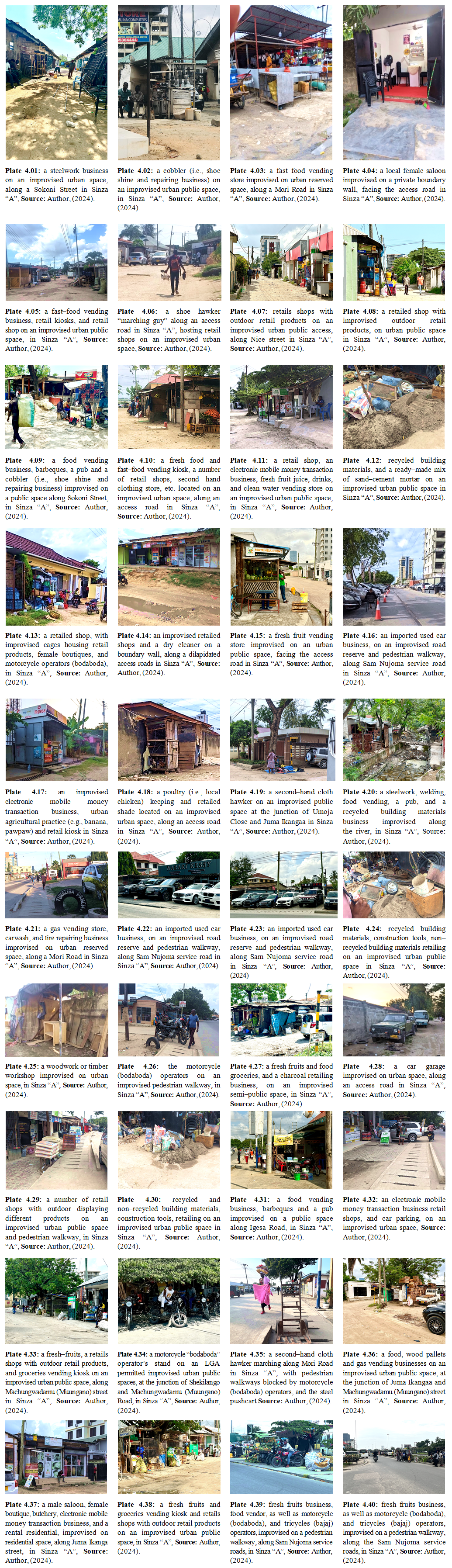

4.3.5. Employment Distribution

- From Table 4.03 results disclosed that; majority of the respondents (i.e., n = 46; 44.7%) were self–employed, owning and running business, involved in a constellation of socio–economic activities (as seen in plate 4.01 to 4.40) on improvised urban spaces. This shows that; self–employment is a key agent in improvising and transforming underutilized or contested urban spaces into economically active zones. Besides, 33.0% i.e., 34 respondents were full time employee in public and private sectors; 12.6% i.e., n = 13 respondents were unemployed; while 6.8% i.e., n = 7 respondents and 2.9% i.e., n = 3 respondents were part–time employee and retired, respectively.

4.3.6. Duration of Living, Working or Doing Business

- From an examination on Table 4.03, the results indicate that; 31.1% i.e., n = 32 respondents had been living, working or doing business in the settlement for about 06 to 10 years. 24.3% i.e., n = 25 respondents been in the settlement for about 11 to 20 years, while 20.4% i.e., n = 21 respondents had been there for about 21 to 30 years. Only 17.5% i.e., 18 respondents and 6.8% i.e., 7 respondents had been in the settlement for less that 5 years and for more than 31 years, respectively. Those who had lived in the settlement for more than 31 years, were able to offer a very detailed experience on an evolution of urban space improvisation and the rapid change on settlement’s physical form. Also, findings revealed that; 53% of the participants had been living, and/or working, and/or doing business in the settlement for more than 11 years and above, forming an attachment to the place resulted by, past activities and maintenance of continuity, i.e., proximity to education facilities, relatives, working areas, worshiping area, health facilities; density; number of customers; pedestrian flow; social networks; etc. In–line with [18,100] the lengthy in residence implies residents and non–residents’ physical attachment or “rootedness” to, and continuity with, the settlement. Additionally, [12] argues that; the formation of attachment to place is connected with the daily feelings of continuity and familiarity.

4.3.7. Professional Qualification

- Relative to the professional qualification held by each respondent; the majority (i.e., n = 25; 24.3%) as seen in Table 4.03, were entrepreneurs involved in a constellation of socio–economic activities as seen in plate 4.01 to 4.40; 16.5% i.e., n = 17 participants were architects, urban planners & quantity surveyors. While, 15.5% i.e., n = 16 respondents, 8.7% i.e., n = 9 respondents, and 6.8% i.e., 7 respondents were into accountants and finance professionally, economist and sociologist, and professional teachers teaching at primary and secondary school levels, respectively. Moreover, 4.9% i.e., n = 5 respondents each were engineers (civil, electrical & mechanical) and medical officers (medical doctors & nurses); 3.9% i.e., n = 4 respondent each were lawyers, valuers & real estate managers, sales & marketing, land surveyors & cartographer; and only 2.9% i.e., n = 3 were ICT specialist in–terms of hardware and software. This illuminated how diverse expertise and professionals with planning, technical, and business acumen, contributes to the informal restructuring of planned urban spaces. This, further show that; urban space improvisation is not solely a survivalist tactic, but a process shaped by strategic knowledge application, and embedded actor’s professional logic.

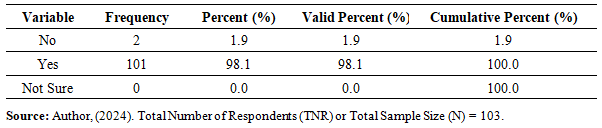

4.4. Existence of the Improvised Urban Spaces in the Planned Settlement

- To establish the existence or availability of the improvised urban planned private or public spaces by the urbanites within the planned settlement, respondents were asked to state on the availability these spaces, from their entire time living in the settlement. The following results were divulged; –

| Table 4.04. The existence of the improvised planned private or public spaces by the residents, within the settlement |

| Figure 4.01. The settlement’s building typologies, and location of different socio–economic or petty trading activities, Source; Author, (2024) |

| Plate 4.01-4.40 |

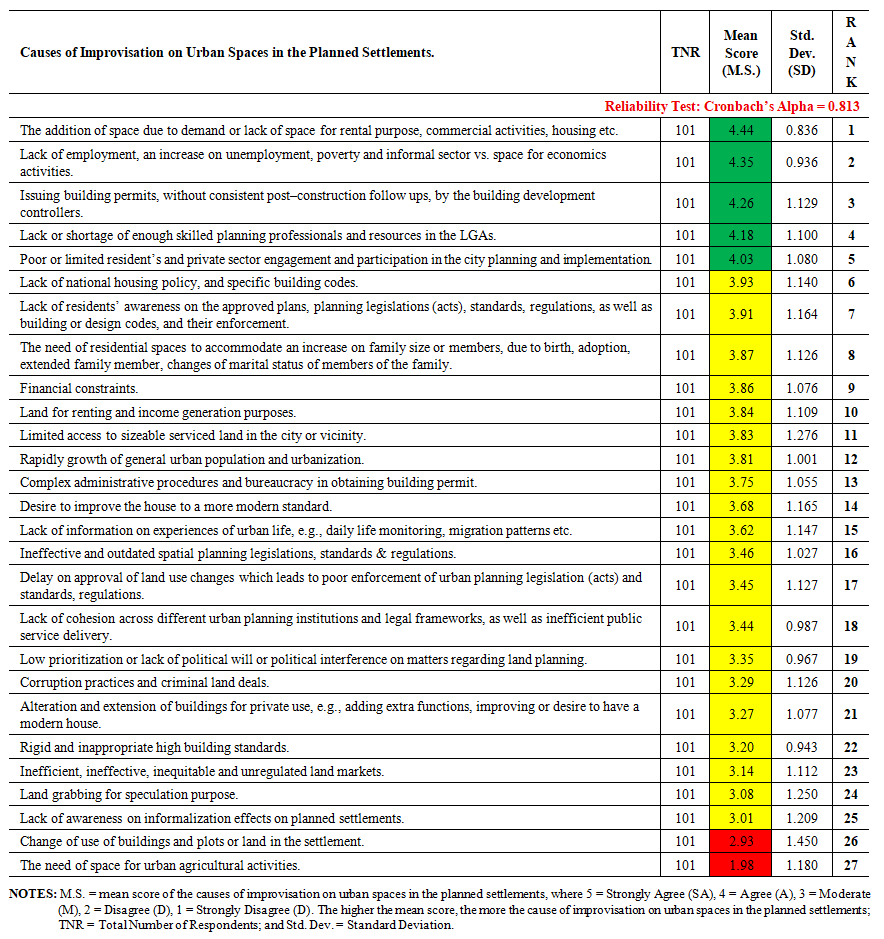

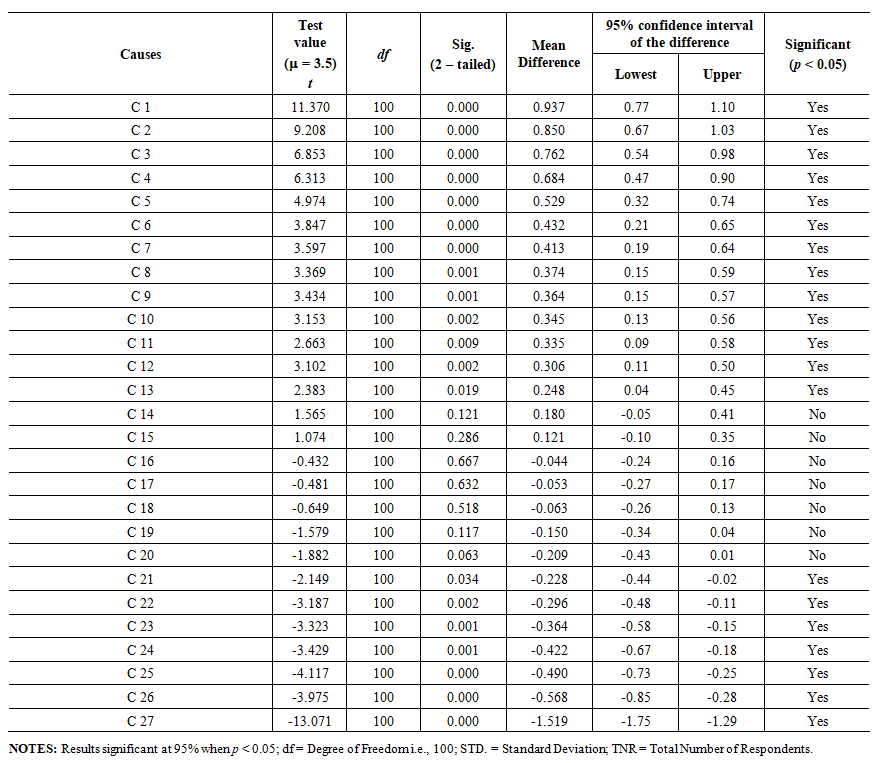

4.5. Causes of Urban Spaces Improvisation in Planned Settlements

- A total of twenty–seven (27) causes were identified and researched on in order to find out the most significant reasons as to why urbanites improvise urban private or public spaces, within a planned settlement; by looking at the its major causes, and the results were as follows; –

| Table 4.05. Presents the causes of improvisation on urban spaces in the planned settlements |

| Table 4.06. Presents the results of one-sample t-test on the causes of improvisation on urban spaces in the planned settlements |

5. Conclusions

- The study concludes that; improvised urban spaces do exist in planned settlements in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania. Out of twenty–seven (27) causes of urban spaces improvisation identified from an extensive literature review, and with a Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient of 0.813; (1) the addition of space due to demand or lack of space for rental purpose, commercial activities, housing etc.; (2) lack of employment, an increase on unemployment, poverty and informal sector vs. space for economics activities; (3) issuing building permits, without consistent post–construction follow ups, by the building development controllers. Other includes, (4) lack or shortage of enough skilled planning professionals and resources in the LGAs; (5) poor or limited resident’s and private sector engagement and participation in the city planning and implementation; and (6) lack of national housing policy, and specific building codes; were highly ranked. The results of the one–sample t–test showed that; including all the highly ranked causes, only ten (10) (out of twenty–seven (27)) identified causes, were statistically significant with p value less than 0.05 (i.e., p < 0.05). Besides, lack of innovation by urban institutions; and lack of or limited use of electronic government (e–government) or electronic communication in decision making related to urban development, in–terms of issuance of electronic planning consent and building permit, application and approval of change of use, application and issuance of business license in relation of the approved surveyed plot and adherence of building standards, etc. were added as causes of n improvisation of urban spaces in the planned settlement, by the respondents via an open–ended question. The paper recommends on; eliminating all loopholes related to overlapping powers between CGA and LGA section; reviewing and enacting the existing regulatory frameworks as well as the existing drafts; equipping CGA and LGA in terms of allocation of enough financial resources, equipment, and ICT tools to eradicate all kind of bureaucracy as well as double allocation, etc.; training and human resources up to Mtaa level; leasing few open public spaces and leaving few for community activity, air circulation, and land banking; and, the involvement of people from the early urban planning and redevelopment stages via bottom–up approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This paper is derived from the ongoing first author’s Ph.D. thesis, titled “Urban Space Improvisation; the Case of Planned Settlements in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania”, supervised by second and third author and advised by fourth author, all from Ardhi University, which has made this study possible though its continuous support, facilitated by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, (MoEST).

Disclosure Statement

- The authors declared no potential competing conflicts of interest.

Participation Consent

- During this study, all respondents were provided with a written consent form outlining the nature and purpose of the research survey.

Notes

- 1. Urban Planning and Space Standards; includes standards for plot size or density, skylines, building lines and setbacks, plot coverage and plot ratio, health and education facilities, golf courses, passive and active recreation, public facilities by planning levels, public facilities by population size, parking, residential areas and agricultural show grounds, standard for electric supply and its way leave for water supply, road width, communication pylons, sewerage treatment plants, ponds, transportation terminals, stream or rivers valley buffer zone, beaches and industrial plots and recommended colors for land uses, [34].2. Urban Fabric is a morphological composition of physical elements or characteristic within an urban area which includes streetscape; open space and squares; the plots; buildings; constructed space; hard landscape e.g., roads, pedestrians, paved car parking, etc.; soft landscape, vegetations or gardens, water ways, etc.; signage; street lightings; building’s texture; texts e.g., graphics; etc., [7,53]. It can be understood by regarding the building as an “object” and space as the “background” [7].

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML