-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2024; 14(1): 1-31

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20241401.01

Received: Jul. 21, 2024; Accepted: Aug. 16, 2024; Published: Sep. 27, 2024

Visual Privacy in Informal Housing Areas; The Case of Mlalakuwa in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania

Mbasa M. Segelela1, Henry M. Rimisho2, Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha2

1Mbeya University of Science & Technology (MUST), Mbeya, United Republic of Tanzania

2Ardhi University (ARU), Dar–Es–Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania

Correspondence to: Henry M. Rimisho, Ardhi University (ARU), Dar–Es–Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Insufficient knowledge of visual privacy in housing areas, has led to some difficulty in addressing housing and planning problems, so as to improve the lives of people in the informal housing areas. “Are the visual privacy mechanism adopted by residents efficient in terms of ventilation, natural light, aesthetics, urban management and space use?” is a question which has not been answered. Using case study as a strategy, the study was conducted in the residents’ understanding on visual privacy, how the residents can achieve visual privacy and its impact in terms of architecture, urban planning and management in housing areas. Data collection tools used included; interviews, observation, measurements, sketches, and photographic registration. Findings revealed that; people perceive “visual privacy” as a condition that allows residents, home owners, and tenants to perform various functions and activities, without being observed by others from within, or from without. Construction of fences to block overlooking from neighbouring houses, use of tinted glasses on windows, louvered windows, curtains, rules and norms are among the measure taken by residents to regulate their desired visual privacy. This research recommends on introducing a system of semi–regularized (guided) informal land subdivisions, so as to avoid or at least mitigate negative effects resulting from chaotic land development. Similarly, a holistic approach to the design of houses which take into consideration issues of visual privacy should be employed.

Keywords: Privacy, Visual Privacy, Housing, Informal Settlements, Mlalakuwa, Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania

Cite this paper: Mbasa M. Segelela, Henry M. Rimisho, Dennis N.G.A.K. Tesha, Visual Privacy in Informal Housing Areas; The Case of Mlalakuwa in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania, Architecture Research, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2024, pp. 1-31. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20241401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Housing is one of the three human basic needs, apart from food and clothing. Access to safe and healthy shelter is essential to a person's physical, psychological, social and economic wellbeing and should be a fundamental part of national and international action. Tanzania is one of the rapidly urbanizing countries in Sub–Saharan Africa. The annual urban growth rate is estimated at around 5.6%, [49]. The total population in Tanzania is now estimated at 44.9 million [49] in which Over 70% of the urban residents in Tanzania live in informal settlements, [46]. Out of 500,000 residential houses built in Dar–Es–Salaam alone, 400,000 or 80% are found in informal settlements, [19]. In Dar–Es–Salaam, there are more than 150 informal settlements, [18]. Housing forms an indispensable part of ensuring human dignity. “Adequate housing” encompasses more than just the four walls of a room and a roof over one’s head, as per the Habitat Agenda, Paragraph 60, [60]. The right to adequate housing as a basic human right means having freedoms such as to be free from arbitrary interference with one’s home, privacy and family; and the right to choose one’s residence, to determine where to live and to freedom of movement, [45]. Despite this, it is estimated that at the present time, at least 1 billion people do not have access to safe and healthy shelter and that if appropriate action is not taken, this number will increase dramatically by the end of the century and beyond. According to UN–Habitat, “for the first time, in 2009, Africa’s population exceeded one billion, of which 395 million, almost 40 per cent, lived in urban areas. This urban population will grow to one billion in 2040, and to 1.23 billion in 2050, by which time 60 per cent of all Africans will be living in cities”, [46]. The rapid population growth in African cities forces these urban households to live in informal settlements (ibid). Housing is essential for normal healthy living. It fulfils psychological needs for privacy and personal space; physical needs for security and protection from incremental weather; and social needs for basic gathering points where important relationships are forged and nurtured. In spite of its spontaneous and improvised character, the informal sector has provided virtually the only appropriate housing, in terms of the organization of the outdoor spaces for the urban poor of the developing countries. The Informal Sector of Dar–Es–Salaam in Tanzania has become the major source of housing supply for residents, as the case is, in most other cities of the developing countries. In the informal settlements, the construction of buildings is done using local artisans and no building regulations and procedures are adhered to. Houses are being constructed incrementally as income increases and the informal settlements are becoming saturated, one may expect the settlements to experience the visual privacy problems. Housing studies conducted in Tanzania (though not on visual privacy) give some indicator of the privacy problem. Research done both in formal and informal settlements shows the need of studying the privacy phenomenon, [3,33,41]. No in–depth studies have been done on the impact of visual privacy to urban planning and architecture, the resident’s perception on the phenomenon in the context of Tanzania housing areas. Taking into consideration the importance of visual privacy to Architecture, planning and residents, this study explores some theoretical and methodological approaches towards addressing issues of visual privacy, within housing areas in the Tanzanian context. One among issues has been analysed are the effects of Visual privacy and assess residents’ perception on visual privacy in housing areas.Housing studies in Tanzania are largely on informal land control [13], community participation in delivery of urban infrastructure in informal settlements [17] and meanings of spaces from users` conceptions [20], density, house forms and plot characteristics in both informal and formal settlements [22], housing transformation and spatial quality phenomenon [33], outdoor spaces and household livelihoods or opportunities for survival [41], everyday architecture of public open spaces in informal settlements, [28]. However, little has been said about visual privacy in housing areas. [41] on his study of Housing Transformation and Urban Livelihoods explained briefly the issue of reduced household privacy in informal settlements as one of the negative effects of transformation. Furthermore, he described overcrowding where conflicting uses are conducted in one room or two, [41]. Although he highlighted the lack of privacy in informal settlements, his studies neither highlighted the resident’s visual privacy perception nor the visual privacy regulation mechanisms employed by the residents.A study by [10] on housing interventions and its influence on urban development concludes that people fence their property for different reasons such as security, privacy, portraying status (prestige) and boundary identification, [10]. Plot demarcation by use of fence is common in housing areas as a means of achieving visual privacy. She highlighted that boundary fencing characteristics in housing areas are of three categories: Those made of permanent building materials, those made of temporary building materials and plots that were not fenced. Houses that belonged to the high–income households seemed to be the most fenced with permanent building materials. These can afford to use concrete blocks or stones. Fences made of hedges can also serve the purpose; the disadvantage of hedges is that like other plants they take time to grow and they need to be cared for. It was noted that pride and social-economic status are among things that the types of fencing symbolize, [10]. She states that fencing to ensure privacy was necessary especially where a house is either close to another house, a road, a path or a public space. In such cases some people may want to conduct their outdoor activities without being exposed to outsiders (ibid.).Similarly, the study by [33] on Transformation and spatial quality highlighted the need for studying issues of privacy in informal settlements, [33]. She found that household activities are conducted in a mixed manner in one room or two thus reducing the privacy (ibid). She observed that “many tenants’ households were observed renting one or two rooms, while the household sizes were in some instances as large as eight members”, [33]. Overcrowding can undermine the visual privacy as revealed on her study. The in–depth study on the aspect of visual privacy in housing areas has not been done in Tanzania.

1.1. Research Problem

- The Millennium Development Goal (MDGs) emphasized the need to “ensure environmental sustainability” and to achieve “a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slums1 dwellers worldwide”. In Tanzania much research has been dedicated to infrastructure upgrading through Land Regularization, infrastructure service provision, and land management. Worldwide studies related to privacy in informal settlements are scanty. Few studies on privacy are conducted in public/social housing, public buildings and Islamic context in planned settlements. The problem is the lack of knowledge on the effects of visual privacy (fear of being overlooked) and how people perceive visual privacy. “Are the visual privacy mechanism adopted by residents efficient in terms of ventilation, natural light and aesthetics, views, space use?” is a question which has not been answered. There is inadequate documented knowledge of what is the status of visual privacy in housing areas, which could be better developed by professionals like architects and planners. Given this knowledge gap, it is particularly difficult to address housing and planning problems in housing areas so as to improve the lives of people. A thorough understanding of this knowledge is important for designers, architects and planners to design houses and spaces as well as to plan housing areas with visual privacy consideration. It will further assist in formulation of policies for addressing the visual privacy impacts in housing.Therefore, this study attempts to understand visual privacy and its impact on urban planning, and architectural design; by understanding visual privacy concept, and the resident’s perception on visual privacy; exploring how “visual privacy” can be achieved in housing areas; and describing the effects of visual privacy to the housing areas in terms of architecture urban planning and urban management in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. This is achieved by ensuring that the existing situation is addressed and worked out, through the following questions like: – what is visual privacy? how do residents perceive visual privacy in housing areas? how can residential visual privacy be achieved in housing areas in Dar es Salaam, and what are the effects of visual privacy to the housing areas in terms of architecture urban planning and urban management in Dar–Es–Salaam, Tanzania. Basically, protecting the residents from being overlooked in the urban environment, can improve their personal feeling, their personal confidence, contributes to control their personal space and prevents penetration of undesirable disturbances, [32]. Certain activities are better performed in spaces where there is no threat of being overlooked by others.

2. Literature Review

- The literature review gives a clear understanding the privacy and visual privacy concept in housing; types of privacy; factors affecting visual privacy in housing areas (both formal and informal housing areas); house response of visual privacy; housing delivery system in Dar–Es–Salaam City; factors affecting perception of privacy; and privacy in western context.

2.1. Privacy

- The privacy definitions generally fall into one of three core categories: privacy as a quality of a person, a quality of the environment, or an interaction between person and environment. These core categories are further partitioned to include privacy as an attitude, privacy as a quality of a place (i.e., a place that affords privacy), privacy as a form of refuge, privacy as a goal, privacy as a behaviour, and privacy as a process, among other definitions, [4]. [2] defines privacy as the control and enabling of access to one’s self, a definition that characterizes privacy as a process that focuses on the physical and psychological aspects of privacy. In human behaviour studies privacy is defined as “selective control of access to the self or to one’s group.” This definition can be equally applied in environmental studies to explores a “display of territoriality, use of space, physical barriers, and other ways of using the environment to obtain and protect privacy”, [4].Privacy is defined as the quality or state of being apart from company or observation. [36] labels privacy as an aspect of the organisation of communication and discusses different mechanisms (termed privacy filters) that are used in order to achieve it. These involve physical, temporal, social and psychological measures which range from spatial distancing and separation to the internalization of personal feelings. Such measures tie privacy to aspects of accessibility, both physically to individuals, and also to information about them. These encompass both measurable and immeasurable variables ranging from physical proximity, distancing and sight to factors such as sound, smell, and behaviour.Privacy affects the circumstances under which people encounter each other and the control of space for personal use. Houses provide loci for encounters for household members, visitors and guests. Building structure and the internal arrangement of rooms in combination with boundary controls such as doors provide settings which allow both meetings and separation, governed by both location and time. Moreover, [38] define privacy as ‘‘the interest individuals have in sustaining a personal space, free from interference by other people and organizations’’. Also, [3] defines ‘privacy’ as means towards achieving security of information contained within the home both of persons and of property and it means ‘something that gives or assures protection and safeguards against external influences infringing on the well–being of the home, the occupants and the properties therein’. Privacy can be defined as the quality or state of being apart from company or observation, freedom from unauthorized intrusion, [52].Visual privacy has to protect residents’ ability to carry out private functions within all rooms and private open spaces without compromising views, outlook, ventilation and lighting or the functioning of internal and external spaces. In order to define privacy safely, one should look at people's culture. A complete understanding of people's culture is necessary in order to understand how people perceive privacy in their own culture. Only after understanding how privacy is perceived by these people, could a precise definition of privacy be formulated. Visual Privacy in this research can be defined as "the protection (controlling mechanism) of the house and its residents (individual or group) from undesired visual observation (interaction)". In this definition, all the possible variables are being covered. These are the space (room, housing unit or compound or outdoor spaces), the individual or group that is observing or being observed, the relationship between the observed and observer, the behaviour that is being observed, the time or occasion, and the agreement on the rules, norms governing privacy.

2.2. Types of Privacy

- [61] points out that there are five kinds of privacy considered in housing study. These are auditory, visual, personal, family, neighbour, olfactory privacy as explained in subsections that follows: –

2.2.1. Auditory Privacy or (Acoustical Privacy)

- This is concerned with privacy of residents from noise of housing areas, it includes speech or conversational privacy and freedom from noise distractions. It can be defined as the quantity and quality of sounds in their relationship to privacy in housing areas. Man is beginning to lose his capacity to discriminate between sound and noise, between desirable and irrelevant, some sounds are deliberately selected for their meaning such as conversation and the sound of radio, others are treated as noise and deliberately rejected such as sound of traffic and noise of dogs barking. The most annoying noises are those which are murky or half clear and those which are sudden, clear enough to represent the possibility of an accident but not clear enough to remain mysterious and frightening. This incidental noise, produced by all kinds of domestic equipment, by neighbours, by heavy trucks outdoor and by distant aircraft is beyond control by residents and the further away the source of noise from individual the more difficult it is to control.

2.2.2. Visual Privacy

- This kind of privacy deals with the visibility of the family members from the outsiders.

2.2.3. Personal Privacy

- This deals with privacy of every individual from the other family members.

2.2.4. Family Privacy

- This is a kind of privacy that concerns family members from non–family members and its relationship between private life of family and friends, guests. It deals with separation of the private life of family members from the others. Similarly, intra family privacy – deals with the privacy of activities of family members inside the house.

2.2.5. Neighbour Privacy

- This kind of privacy deals with privacy of family members from their neighbours. Urban privacy – this deal with the privacy of family members in the neighbourhood. It also deals with the desire for living in crowd or more private types of thoroughfares. Hence by considering the different kinds of privacy this research deals with visual privacy of a person and family members.

2.2.6. Olfactory Privacy

- Means the absence of objectionable or un wanted smells, and similar to auditory privacy, it is difficult to achieve in the single-family housing areas. The degree of this form of privacy required by an individual varies according to the activities he/she is undertaking and his traditional experience. For example, the smell of a neighbour’s burning leaves might not be objectionable when one is working in the yard, but becomes objectionable and intrusion of privacy when one is eating in an outdoor dining area. Smoke, garbage odours, and automobile exhaust fumes all have some detrimental effect in varying degrees on the enjoyment of private open spaces in housing areas. It can be reviewed that, auditory (acoustical), olfactory and visual privacy are the most common types in the housing areas. Considering the time available for the research, availability of literature, only visual privacy has been considered in this research. However, the theories and concepts are equally applied in all types of privacy.

2.3. Factors Affecting Visual Privacy

- [54] in her survey study of “overlooking” explained that this aspect of privacy, more than any other aspect, was dependent upon the appropriateness of the relationship with others in social terms. She found out that the nature of this relationship could range from almost no involvement and high control over the relationship to varying degrees of involvement and intimacy with neighbours. Willis listed ten factors affecting this privacy. They were as follows: physical setting and social relationships, the individual, social factors, physical variables, space arrangement of entrance doors, street form, proximity, neighbourhood satisfaction, neighbourhood interaction, habitat selection.

2.3.1. Personal Factors

- Differences in privacy behaviour, beliefs, values, preferences, and expectations originate with differences in personal characteristics and differences in situations. Some of us, because of our culture, personality, or other characteristics, require more privacy or express our privacy needs differently from others.

2.3.2. Situational Factors

- People’s preferences for and satisfactions with privacy vary with the situation, that is the physical setting or the social atmosphere. The environment itself might lead an individual to have greater privacy preferences or lower satisfaction with privacy.

2.3.3. Cultural Factors

- The result of [54] study and survey showed that privacy requirements may vary also within cultures according to socio–economic grouping, lifestyle, family background and values, etc. She also, pointed out that the concept of privacy was relative not only to cultures and groups of people, but also to individual members of a community. Different individuals may have varying privacy requirements. Individual differences in relation to privacy had been found, in her study, to be related to sex and age, age–related experiences (life stage, family life cycle), past (history of the person) and present (living situation) experiences or circumstances, personality variables (introversion-extroversion), and mental health. In some Arab societies, families want to live in houses with high solid walls around them. For example, homes in Arabian society are constructed so that the residents of the house cannot see their neighbours from any part of the house, thus insuring the privacy of the neighbours. Elsewhere, housing patterns can be different.

2.3.4. Spatial Factors

- Many scholars like [2, 37], have stated that, the hierarchy and sequence of spaces and the juxtaposition of these spaces is the determinant factors in regulating privacy. Public spaces always have been referred to as spaces where most social activities take place (living areas) and social integration is promoted with unrestricted visibility, aural and accessibility. Private space, in contrast to public areas used to be more segregated (bedrooms, female domains) and offers more privacy, secrecy, concealments and isolation from the attention and interest from the public that constitutes with visual, aural and accessibility restriction. Public space, basically dominated by male, and can be defined by the absence of women, as per the existing literature. There are five factors that affect the way human beings perceive their surroundings and accordingly the mechanism by which they control privacy. These factors are Accessibility, visibility, proximity, vocals and olfactory. Spatial boundaries act as additional means for regulating (limiting or increasing), the communication of the individual with its surroundings (ibid.).

2.4. Housing Delivery Systems and Schemes in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania

- [59], states that “apart from shelter as the most pervasive, housing offers other services such as indoor cooking, sanitary and storage facilities, or the assurance of privacy and rest, or the provision of space for recreation and children’s education, which depend a great deal on income, climate and traditions”. [40] defines a house as distinctive spaces in which individuals come together in intimate relationship, claiming the control of these spaces for privacy and comfort. A house has to fulfil a number of functions like security, protection from incremental weather, and privacy. Housing delivery schemes in Dar–Es–Salaam city includes:

2.4.1. Private Housing Scheme

- The private sector’s participation in housing in Tanzania is higher compared to the public sector. This includes housing in both formal and informal settlements. Small–scale private landlords in rental housing dominates the informal sector supply of urban housing, [29]. In informal settlements the greater part of houses produced by this sector is non–conventional, does not comply with laid down procedures and is frequently contravening existing regulations (ibid). Regulations pertaining to plot coverage, plot ratio, setbacks which have impacts on visual privacy, are normally not adhered to during housing construction.

2.4.2. Sites and Services Schemes

- In the decades of the 1970's and 1980's the Ministry of Lands, with the assistance of the World Bank, implemented Sites and Services Project in Dar–Es–Salaam, Mwanza, Mbeya, Morogoro, Tanga, Iringa and Tabora in two phases. The aim was to plan and survey 29,917 new plots and upgrade 23,811 houses by providing services roads, water and schools. Over 467,000 people living in squatter areas benefited from this Project. In the 1990's the Ministry of Lands implemented a site and services Project on its own resources in Tegeta and Tabata areas of Dar–Es–Salaam where by 5,000 plots were planned and surveyed. The objective for this project was to pre-empt potential squatter areas and provide basic services to existing ones. While the intention of the third phase site and services project was also to upgrade 40,000 houses in Kinondoni Shamba, Hanna Nassif and Mwananyamala areas, the third phase never took off, as, no funds were made available and the scheme had to be abandoned.The evaluation of the National Sites & Services scheme has been with mixed reactions. It is generally pointed out that the programme did not benefit the targeted population, [26,43]. The main problem with the scheme was (again) the way it set standards that were simply too high for local conditions to be afforded by the poor. Its shortfalls were also connected with the bureaucratic set up of the regulatory procedures [12] and the delay in the project implementation, which escalated the costs, hence magnifying the affordability problem. Dwellers were not able to contribute to the costs of the provided core housing and the associated infrastructure.

2.5. Housing Areas

- Housing areas in this research can be described as housing units constructed either in formal and informal settlements. In Tanzanian context it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between the two settlements. Seventy percent of the urban inhabitants live in the informal settlements in Tanzania, [48].

2.6. Formal Settlements

- Formal settlements are settlements that develop according to all required urban planning, design, and development regulations. These include legal or right ownership of the land, development procedures, and occupancy process. Formal settlements in Dar–Es–Salaam are gradually being affected by the informality phenomenon, due to unauthorized house transformation, redevelopment and other construction activities, [64].

2.6.1. Building Permits Application in Formal Settlements

- Once a developer is ready to begin development project on the allocated land, she or he will require a building permit. The permit application must be processed at the local authorities administering the area where the property is to be located. An applicant is supposed to fill application forms for planning consent (2 copies). These forms require the address or location and planning zone of the proposed development, the number of plot and the intended use of the buildings or land, the purpose for which the land was last used, a general description of the development, the area and circumference of the plot, the width of the street opposite, and the building line or set–back of the adjoining building. The following documents are also required when applying for a building permit: -§ Four copies of Building Plan showing architectural or engineering drawings and calculations, including site layout and location plans, elevations, sections of the building including storm water drainage, fire protection, driveways and parking,§ Notice of intention to erect or alter a building. This form shows the name and address of the developer or owner, intended use of the building, estimated costs of construction, number of storeys, and the area (in square meters) of each storey,§ Copy of certificate of Title Deed or the Letter of Offer to show land ownership, he or she wants to build on, and§ Receipt of payments of land rents, permit fee, and other statutory fees.The application then is forwarded to various departments including fire department, health department and planning department. Each of these departments must approve the project. To speed up the approval, the applicant should normally make follow up with each of these departments personally. After getting approval from the said departments, the Municipal/township engineer approves the plans first, before submitting the application to the City Council or Township Council for final approval. For the case of Dar-Es-Salaam, the approval committee meets (once in 3 months, but can be less in special cases. The number of meetings differs from one municipality to another) to make final approval of the building permit. In most cases, that is where delays start. Sometime the local authorities do not sit regularly as they are supposed to do.Other issues are also looked at when one applies for a building permit. For instance, Section 29(3) of Urban Planning Act No. 08 of 2007 provides that, where in connection with an application for planning consent to develop land and subject to any other relevant law, the Planning Authority is of the opinion that proposals for industrial location, dumping sites, sewerage treatment, quarries or any other development activity shall have injurious impact on the environment, the applicant shall be required to submit together with the application the Environmental Impact Assessment report.

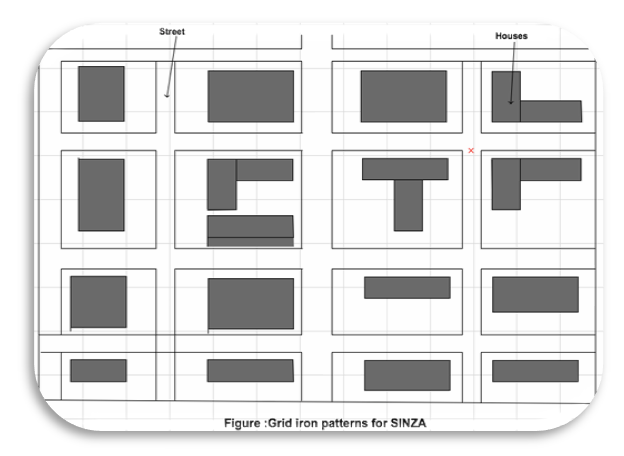

2.6.2. Visual Privacy in Sinza Formal Settlements

- Sinza was designed as a residential settlement for low-income people under the site and services schemes of the 1970’s, [22]. The standard plot size was 288 square metres. By that time, this was the smallest plot size which was considered affordable by the low–income people. Houses are very similar to those of Mlalakuwa but they are planned unlike those of Mlalakuwa, Sinza has five neighbourhoods namely A, B, and C. Starting from mid 1980, commercial uses started to emerge in Sinza. These included retail shops, guest houses, hotels, small groceries, restaurants, service industries, social halls and boutiques, [22]. Middle- and high–income people have been buying off low–income people and reconstructing larger high–rise commercial residential buildings. Most of the houses are gated for security purposes unlike Mlalakuwa. Gates are made out of steel and the fencing walls are of sand–cement blocks. The changing landscape of Sinza is largely attributed to the increase in land value following the establishment of the Mlimani City commercial complex and completion of the Sam Nujoma highway that marks the border with Sinza, [23].

| Figure 2.1. Sinza cluster. Source, Authors, (2023) |

| Figure 2.2. Grid iron patterns for Sinza, Source, Authors (2023) |

2.6.3. Visual Privacy in Kariakoo Formal Settlements

- The study by [27] on urban transformation and changing building types in Kariakoo argues that Kariakoo has dramatically transformed from a largely low–lying single storey building fabric in the 1970’s to an increasingly dense collection of multi–storey buildings developing within a tight and unchanging plot and street structure.

| Figure 2.3. A small side setback creating undesired visual privacy, Source; [23] |

| Figure 2.4. Overlooking from multi-storey buildings with in the Kariakoo area, Source: [27] |

2.7. Informal Settlements

- Informal settlements in the context of Tanzania refer to housing areas which have developed outside official land development process and procedure [33], or informal settlements2 are not formally–planned urban settlement that houses the urban under–class which has poor state of infrastructures facility, service provision and spatial quality. [44], define informal settlements as: residential areas where a group of housing units have been constructed on land to which the occupants have no legal claim, or which they occupy illegally; or unplanned settlements are areas where housing is not in compliance with current planning and building regulations (i.e., unauthorized housing). Given that a large and increasing proportion of these housing areas lack assistance from state and municipal agencies, the tendency is for both state and city actors and a wide range of researchers to define them as “informal”, [12].

2.7.1. Characteristics of Informal Settlements

- Apart from Lack of land tenure security, lack of basic infrastructure and predominance of physically sub-standard dwellings; the following are common characteristics of most informal settlements irrespective of their status (legal or illegal) includes the following: -§ They are built by the inhabitants with the intent of owner–occupation, renting or both,§ They are built, for the larger part, by low–income urban dwellers for which the existing formal housing systems or markets are hardly realistic options. Higher income residents are also found in these settlements,§ The houses are built primarily with informal financing methods, i.e., family savings, capital from inheritance, sales of inherited land or savings from informal credit associations,§ The builders employ local building materials, skills, designs and indigenous technology depending on affordability,§ Often builders do not adhere to formal/legal building codes and planning standards,§ The informally built houses exhibit high variations in types and quality of construction, ranging from traditional construction materials (e.g., mud and pole or thatch) to modern quality components (concrete blocks, corrugated iron, aluminium, zinc, or tin roofs),§ They are built and serviced incrementally, ensuring flexibility on the part of builders and owners,§ They can exhibit unique urban designs with significant variations in lay–outs and spatial arrangements,§ Their densities are normally increasing rapidly up to a saturation or over–densification stage, and§ The land use patterns are highly mixed, including small industries and urban agriculture.Other features common to many but perhaps not for all informal settlements include overcrowding, the majority of the structures provide accommodation on a room–by–room basis, the majority of dweller being of low incomes and living as tenants in a single room, predominantly engaged in informal economic activities, presence of small–scale and large–scale landlords; composed of heterogeneous urban population; rental accommodation being the most common form of tenancy, [29]. Above all these, settlements offer an affordable alternative for shelter for many poor households.

2.7.2. Housing Construction in Informal Settlements

- Building construction in the informal settlements is done without much restriction. Local artisans (“fundi”) are the one involved in the design and construction of houses, [33]. They are not necessarily following any building regulations. Land owner is free to erect any structure, sometimes without any drawings. It is only when one needs to build a multi–storey building when he or she looks for expertise of an architect and a structural engineer. Houses, found in the area vary, from those made of mud and pole, cement sand block to multi–storey structures. The pace of building depends on the amount of money one has. There are rich people who build and complete a house and there are also those who build one or few rooms, occupy them first, then gradually adding more rooms over time. The extensions take place as one gets the fund through saving (this is what is referred to as incremental housing). In Tanzania, there is a resemblance in terms of physical character of building forms in formal and informal settlements, [22]. He further argues that despite some settlements being informal, good quality houses can be found in these settlements that are comparable to those in formal settlements.

2.7.3. Informal Settlements and Visual Privacy Phenomenon in Tanzania

- In Tanzania informal settlements accommodate a wide range of social and economic groups of people, from poor to wealthy households. This is contrary to the situation observed in many other countries where a strict demarcation of the two groups of people is notable, [13]. Government policy on informal settlements has generally been supportive, except for housing on flood prone areas. The 1999 Land Law gives the right to own land through customary tenure. The construction of residential houses in these settlements are not regulated compared to housing in formal areas where one has to abide to planning regulations on land use, setbacks, plot coverage, plot ratio all of which have an impact on the visual privacy. Zoning codes and building by–laws utilize standards that can be easily applied. Specific setbacks, floor area ratio, plot coverage, height and width limits are factors which can be measured by an inspector and thus furnish convenient building controls. The purpose is to safeguard health and safety, fire protection, light and air provision, and for provision of spaces for outdoor activities. They also contribute towards determination of visual form of residential environment. Thus, it can be said that space standards/regulations in residential house affects the visual privacy of residents in their environment.Privacy in residence is mainly concerned with minimum physical distance between housing units, the relationships between doors and windows and the relationship between peoples. Land tenure relevant to informal settlements is vested in the state. The President has right to all land in the country. The president may acquire any land for public use, provided fair compensation for exhaustive development is assessed and paid. Land has value [47] together with the developments made thereon. Residents of informal settlements subdivide plots according to the affordability of buyer for housing purposes. Some plots may be small to extent of affecting the visual privacy between neighbours. Densification of informal settlements is caused by increase in the number of houses and population within the settlements. Most of the houses in informal settlements are characterised by single storey house types depicting horizontal densification, [33]. Proximity between buildings has an impact on the visual privacy. The dwellings are low-cost, often built on incremental basis and the settlements usually have a higher population density than formal areas of housing.

2.8. Factors Affecting Perception of Privacy

- Privacy can be perceived differently by different people. Privacy is the outcome of the influence of various parties involved. [36] explained that a wide range of factors had been, theoretically or empirically, shown to relate to privacy needs. He noted how variables were conceptions and definitions of privacy from culture to culture, The result of [54] study and survey showed that privacy requirements may vary also within cultures according to socio–economic grouping, lifestyle, family background and values, etc. She also, pointed out that the concept of privacy was relative not only to cultures and groups of people, but also to individual members of a community. Different individuals may have varying privacy requirements. Individual differences in relation to privacy had been found, in her study, to be related to sex and age, age–related experiences (life stage, family life cycle), past (history of the person) and present (living situation) experiences or circumstances, personality variables (introversion–extroversion), and mental health.One of the most complex aspects of privacy concerns privacy from, or between, neighbours. [54] in her survey study of "Overlooking" explained that this aspect of privacy, more than any other aspect, was dependent upon the appropriateness of the relationship with others in social terms. Willis listed ten factors affecting this privacy. They were as follows:§ Physical setting and social relationships,§ Street form,§ The individual,§ Proximity, and social factors,§ Neighbourhood satisfaction, and interaction,§ Physical variables,§ Space arrangement of entrance doors, and § Habitat selection.

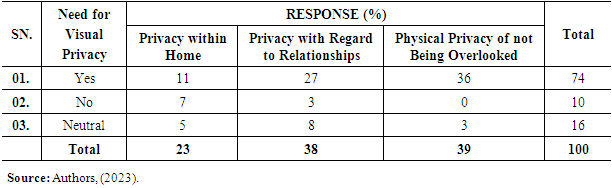

2.9. Privacy in Western Context

- For the purpose of this research, the term 'western context' covers, geographically, Western Europe and North America. It is included in this study because Tanzania was at one time colonized by these countries in the 18th and 19th centuries. Thus, the political, economic, urban planning and cultural influence on the population of Tanzanian may have been influenced by these countries. In terms of urban planning, zoning of our cities into higher densities, low densities, and medium densities is largely inherited from our former colonies. Similarly, the words like “Uzunguni, Uhindini, Uswahili” all are results of our former colonies, [65]. Tanzania was influenced in that period, and afterwards, by their colonisers, or former colonisers, in a process that was known as “modernisation”. This influence continued even after the independence of Tanzania, but in an indirect form, such as economic, technological and in some cases political prototypes. Therefore, it is essential to look at the privacy concept and its perception in Western cultures, in order to understand how this concept, later on, was inherited by Tanzania from the cultures of their former-colonisers.Moreover, literature shows that; the traditional organisation of spaces in large and small houses in Europe from the Middle Ages to early modern times, consisted of a matrix of discreet but thoroughly interconnected rooms. Occupants had to pass through one room into another, and most probably household members had no personal physical privacy in the sense in which it is understood today. In the 17th century it was challenged and finally displaced in the 19th by the corridor plan, which is appropriate to a society that finds carnality distasteful that sees the body as a vessel of mind and spirit, and in which privacy is habitual. Evans added that in the 19th century, it was no longer necessary to pass serially through the intractable occupied territory of rooms with all the diversion, incidents and accidents that they might happen. Instead, the door of any room would deliver you into a network of routes from which the room next door and the furthest extremity of the house were almost equally accessible. Furthermore, doors, not merely curtains, separated rooms for the first time and gave individual's privacy from other occupants in the house. The new pattern of dwelling layout allowed the preservation of the singularity of each room by its opening into the thoroughfare.[63] gave another interesting picture of privacy in English houses. He explained that the first step was a bed of one's own. In the Middle Ages, beds, if they were available at all, were liable to be shared even with complete strangers. The next step was segregation of the sexes into separate bedrooms, as in the 17th century. Then, [63] discussed the internal pattern of space arrangement to be found in English houses. He claimed that "the ideal of three bedrooms–one for parents and one each for male and female children–was not seriously entertained as a universal standard until 1935, when the special overcrowding survey was undertaken. The concept of privacy as discussed in western context values an individual privacy rather than family or household privacy.The study, conducted by Margaret Willis, a sociologist, in 1963, covered twenty–five people living in flats and houses in Greater London. All those interviewed were asked to define privacy. The responses of the interviewees seemed to fall into three distinct categories. These were privacy within the home, privacy in regard to the relationships with other people such as neighbours, and the physical privacy of not being overlooked. Relationships with other people were the most frequently mentioned. She, also, found out that the requirements for privacy were usually attributable to overlooking and neighbourhood relationships, whilst internal privacy (personal privacy of individuals within the house itself) was not very important for working class people. The privacy concept differs from culture to culture, society to society, even within one society there may be variation in the meaning of privacy. [25], in the thesis on privacy in row houses, examined and explored the notion of privacy through a multidisciplinary literature review and its link to the row houses. Consideration on the social–cultural conditions in design for privacy was emphasized. The study concluded that.... “In addition to the application of design mechanisms, privacy also relates to the specificity context in matters such as time, place and values which include cultural, social, and psychological variables. These variables (time. place, and values) exist between residents and their domestic environment, determine the needs for privacy” …. [25].[24], when studying privacy control as a function of personal space in single–family homes in Jordan, investigated privacy control expressed by quality and quantity of bedroom space in single–family homes. The presence of certain physical components in personal bedroom space that may satisfy the overall feel of privacy control at Al–Ferdous Community was evaluated. The study concentrated on the bedroom spaces, other spaces like kitchen, semi–public, outdoor spaces within the household was not analysed. Discussing the “concept of crowding”, [51] illuminated the many aspects of “privacy”. One of the many aspects is that arising from Mitchell’s findings that: “lack of privacy is mainly a question of sharing one’s dwelling with other households and not so much dependent on the number of people in a dwelling or the amount of floor area per person”, [51]. Here the discussion was relating this with crowding in Swahili houses in Magomeni. The second aspect highlighted by [51] is that based on social context, defining “privacy” as something else: for instance, that each individual has a room of his own, that there are separate toilets, or that the maid lives away from the (upper class) family.[9] conducted an in–depth interview involving 11 case studies of Malay families living in three–bedroom two–storey terrace housings in the urban areas to study the behavioural norms and territoriality as part of behavioural and environmental mechanisms used to regulate privacy among urban Malay families. The findings of this study stated that, behavioural norms according to culture and religious belief of the Malays remain to be important behavioural mechanisms in regulating privacy among Malay families living in terrace housings. These privacy regulation mechanisms include§ Respecting the neighbours’ privacy by controlling noise in one’s house,§ Avoiding looking into the neighbour’s house particularly when the house is directly facing another house,§ Restricting interaction with the neighbours during certain period of time, and§ Tolerating occasional intrusion within a neighbourhood.The study also shows that; the privacy of the family is affected if they have relatives spending the night in their houses or having male guests in the house. To maintain privacy, the families seldom accommodate their relatives. In a number of cases, male guests especially neighbours and friends are entertained in the porch areas. Findings also indicate that the majority of the respondents have minimal interaction with their neighbours partly due to the minimal time for interaction due to work and family commitment and the need to respect the neighbours’ privacy when at home.

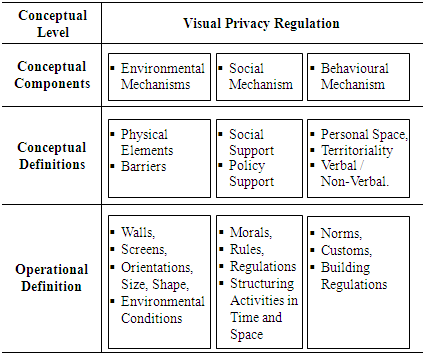

3. Theoretical & Conceptual Framework

- In reference with the definition of theory and proposition by [21], as well as concepts by [30]; the concepts and theory are equally applied to other types of privacy such as audio, personal etc. Theories used in this study includes; –

3.1. Control Theory of Privacy

- [53] is concerned with informational privacy, that addresses one limitation as noted in Altman’s theory – that people may experience feelings of privacy without actually protecting their private information. Altman enlightens privacy mechanisms and the environment while Westin examines the information exchange aspect of privacy. He also identifies four types of privacy (solitude, intimacy, anonymity and reserve). 1) Solitude: – this is when the person is alone and free from observation by others in a space, [35] refers solitude as placing yourself in a situation where other people cannot see or hear what you are doing, e.g., going to bedroom and closing the door, which permits a person to be undisturbed,2) Intimacy: – this is when the person is open, but they are only open with a specific person or people,3) Anonymity: – this is when the person is in a public space and in the presence of other people, but can experience a sense of privacy because they do not know the people around them, and 4) Reserve: – this is when a person may be in the company of friends but they hold back certain information in order to maintain a desired level of privacy.[36] added that the control of interaction and information flows (i.e., privacy) occurred through many major mechanisms to reduce stress in human settlements. He elaborates that; unwanted interaction could be controlled through five mechanisms which are explained here under; -

3.1.1. Rules

- This is a specific cultural device that controls the appropriate amounts of information, habits and ways of controlling, reducing or increasing interaction and information. Religion, norms, and unwritten rules about the relationship of proximity and neighbouring rights and obligations, use of space for various activities, proximal rules, sex roles and behaviour, language and many others are examples of these cultural rules or devices. Some of these have environmental indicators, such as territorial and domain divisions, and others have time indicators.

3.1.2. Psychological Means

- A common defence against overload is to ignore the physical and social environments. With large numbers per unit area, the number of people known byname drops and anonymity increases as a defence mechanism. Other forms are withdrawal, "turning off', dreaming, drugs, depersonalisation etc. Psychological means are the last defensive device and retreated to only after all controlling mechanisms fail to cope with interaction and information overload.

3.1.3. Temporal Means

- People usually control interaction and information flows through structuring activities in time so that particular individuals and groups do not meet. Time rules and time allocation also relate to space use and activities through jurisdiction, so that activity systems in urban areas are intimately related to temporal rules. Such rules can sometimes substitute for spatial and physical defences but can also cause problems in heterogeneous environments.

3.1.4. Spatial Separation and Distance

- The control of space is related to territory and the rules which go with it. Territory is a particular area (or areas) which is owned and defended whether physically or through rules and symbols which identify an area as belonging to an individual or group. One way of controlling territory, i.e., controlling information and interaction, is through the use of space and distance among houses and groups with different areas having different uses and status.

3.1.5. Physical Devices

- This includes walls, courts, doors, curtains, locks-architectural mechanisms which selectively control to filter information. In most cases, of course, multiple mechanisms are used but particular ones are stressed and they are combined in different ways. Based on Westin control theory of privacy, visual privacy can be described as "the ability to control visibility, to have options, and to achieve desired visual privacy". The underlying statement is that ability to control the visual privacy from the surrounding environment.

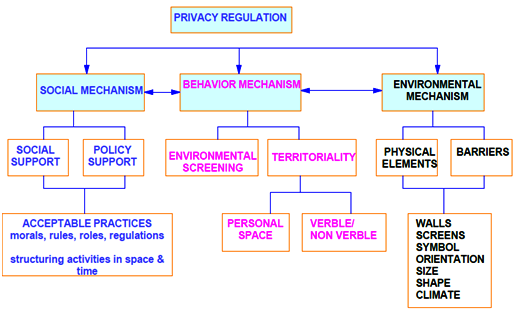

3.2. Privacy Regulation Theory

- Privacy as boundary regulation was first explored by [2] in his Privacy Regulation Theory. Altman’s theory of privacy helps to elucidate how environmental and interpersonal circumstances motivate and in turn are affected by privacy–related behaviour. Dialectic refers to the tension between the desire to be open with other people and the desire to be closed or private. In this study dialectic may mean the desire to be visible or not. [31] describe dialectic process of privacy as one in which forces to be with others and forces to be away from others are both present, with one force dominating at one time and other being stronger at another time. Being alone too often or for long period of time (isolation) and being with others too much for too long (crowding) are both undesirable states, [31]. [2] focuses specifically on the mechanisms that enable people to attain their preferred level of privacy. The privacy mechanism includes verbal and paraverbal behaviour (communication using body language or other signals), personal space, territory (ownership or possession of objects or places), and cultural mechanisms such as norms and customs. Because these privacy mechanisms represent different ways of being private, one can achieve the desired level of visual privacy in one way (for example, verbally by speaking), but not in another (for example, when one’s personal space is invaded). Many literatures have suggested that environmental mechanism, which is by means of territoriality and marking boundaries are the most practical mechanism used in achieving an adequate level of privacy, in comparing with behaviour mechanism (managing their psychological distance from others via verbal and nonverbal means; such as voice characteristics and eye contact). A study by [55], suggested that space should be supportive of the user’s desire and expectations of privacy and perceive privacy as a dynamic property in spaces, by creating options or places of release from contact and observation.

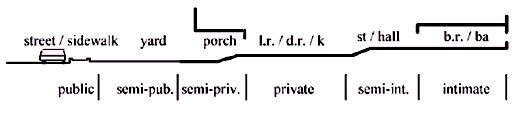

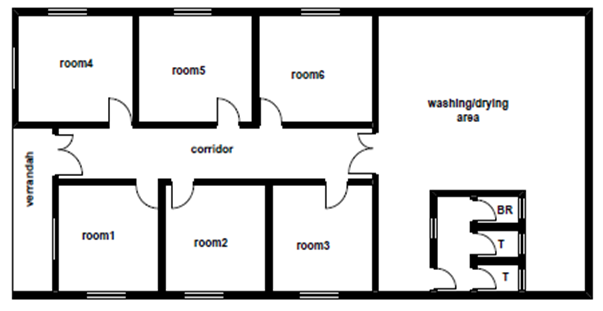

3.3. Concept of Territoriality

- Territoriality can be defined as “the action by which organism lays claim to an area, personalizes it, and defends it against members of his or her own species”, [2]. [2] views privacy as the central concept among the processes. Personal space and territoriality are, in his model, mechanisms by which a person regulates privacy, [2]. Desiring privacy, an individual seeks a particular kind of territory. When people need privacy, the need for territoriality arises. Privacy in people is achieved by the creation and controlling of Interpersonal boundaries. Territories are geographical areas that are personalized or marked in some way and that are defended from encroachment, [42]. [2] identifies three types of physical territories: primary territories, secondary territories and public territories. [37] perceives privacy as a static, inherent property possessed by different kinds of spaces. By observing typical Midwestern single house plans she initially stated, that there are three territorial types namely “public–linking to the outside world, private–relating to community activities within the residence, and intimate-activities linked to the individual”, [37]. Different methods can be used to achieve visual privacy in these different territorial types. The level of visual privacy required depends on location of the space in a territory. [37] has expanded these three territorial types to seven. She calls the seven levels of privacy (zones) as a territorial gradient (public civic domain, public neighbourhood domain, semi–public or collective domain, semi-private domain, private domain, semi–intimate domain, and intimate domain) fig. 3.1. Accordingly, the layers of space within the house and between the house and the street create a gradient from the most intimate space of the individual to the public arena where the life of the urban community takes place.

| Figure 3.1. Layers of space within the house and between the house and the street, Source: Authors, (2023) |

| Figure 3.2. Conceptual framework for visual privacy, Source: [7] |

|

4. Methodology

- The methodology used in this study was survey methodology, with the research design being a case study as per [56–58], in which questionnaire and interviews prepared in accordance with objectives of the study, were used by approaching various Households, Community Leaders within the Mlalakuwa informal settlements, as well as Town Planners, Engineers and Architects. An interesting aspect mentioned in the definition of [56] is that case study entails investigation of a contemporary phenomenon, i.e., visual privacy, as far as Tanzanian experience is concerned, hence the justification of using case study. Moreover, the “case study” was used due to research questions raised being exploratory and descriptive what or how, and the fact that; case study is normally preferred when the questions of how or why are posed, as per [58] writings, and its allowance of the use of multiple evidences such as documents, artifacts (which are in the domain of survey and archival analysis), interviews and observations.Basing on the research questions, the study units of analysis, and in line with [11,34] writings comprised of various Households, Community Leaders within the Mlalakuwa informal settlements, as well as Town Planners, Engineers and Architects, who were also key informants during data collection, given the fact that the case study strategy recommends the use of multiple sources of information as per [57]. Data was collected via interview with households regarding their perception on visual privacy, visual privacy mechanisms they employ and the effects of visual privacy in the housing areas. Household size determines the necessity for visual privacy; the bigger the household size the higher the need for visual privacy. This is why it was thought important to study the household size. Marital status of the respondent has an impact on the visual privacy phenomenon. This is because married couples are expected to have children and other dependents all living in one house or room. The need for privacy varies with gender and age. Thus, gender and age group of selected respondents in this study as seen in Table 4.1.

|

|

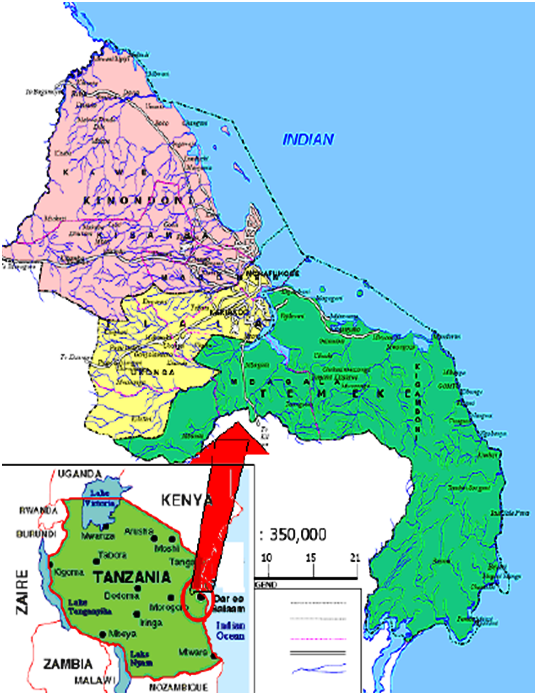

4.1. Selection of the Study Area

- The study was conducted in Dar–Es–Salaam which is the capital city and major business city of the United Republic of Tanzania. Out of the four cities3 in Tanzania, Dar–Es–Salaam has seven times the population of Mwanza, the second biggest city. Dar–Es–Salaam city comprises of five municipalities i.e., Ilala, Temeke, Kigamboni, Ubungo and Kinondoni. The urban population is about 4,500,0004. The biggest proportion of Dar–Es–Salaam city residents (75% – 80%) live in informal settlements (i.e., unplanned settlements), a higher figure than in other urban areas [6], with 80% to 90% of the housing stock built in the area. Although informal settlements continue to grow in all direction their greatest concentration is in Kinondoni District5. Mlalakuwa was selected as a case study area for a number of reasons. The settlement is considered due to its information richness for this particular study. It is an extreme case considering that it is one of the settlements which is at saturation point. Studies by [14], makes this study area viable for research due to availability of some documents for the study.

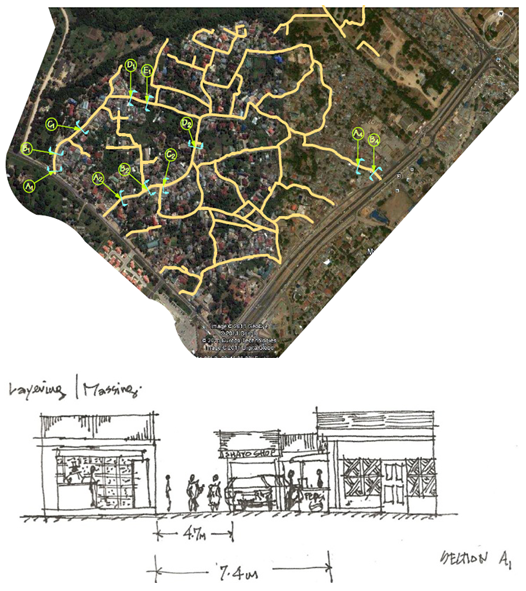

| Figure 4.1. Parts of the Mlalakuwa’s informal settlement study area, Source: Google Map, (2022) |

| Figure 4.2. Parts of the Mlalakuwa’s informal settlement study area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

4.2. Description of the Study Area (Mlalakuwa)

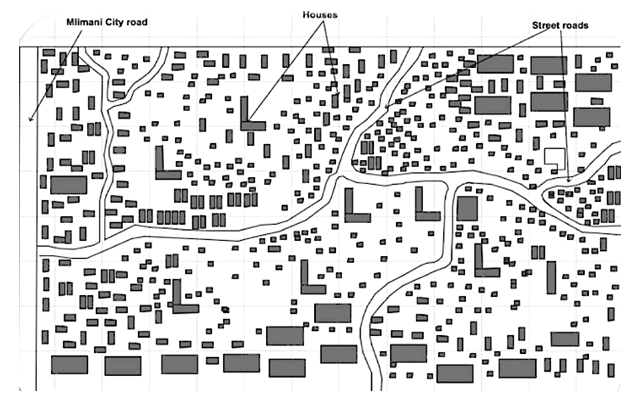

- Mlalakuwa is one of the informal settlements in Kinondoni Municipal in Dar–Es–Salaam City. Dar–Es–Salaam has been selected as a study because is the largest urban agglomeration in Tanzania and is one of the rapidly urbanising cities in the country with a bigger population compared to other urban centres. A number of researches on housing have been done for Dar–Es–Salaam and therefore background information is readily available. Studies by [2,33,41]; and many others have been a stimulant to have Dar–Es–Salaam as a case study. Mlalakuwa is a type of unplanned settlement that has aroused due to the presence of institutional facilities like the University of Dar–Es–Salaam and The Ardhi university and the military of Makongo. Most people residing at Mlakukuwa work at the two academic institutes or at the military, the town of Mlalakuwa grew because of it is near to the working area people can just walk or take one daladala to the working station.Street or Road Pattern or ClusterAt Mlalakuwa there have no defined road patterns the roads are narrow with no light making difficult of two cars to pass at a time and darkness during the night that could increase risks of robbery and theft although its outer boundary is defined with a highway road of Sam Nujoma and a tarmac survey road, Refer the figure below: Fig. 4.3.

| Figure 4.3. Cluster patterns in Mlalakuwa, Source: Authors (2023) |

| Figure 4.4. Overcrowding of houses in one of many parts of Mlalakuwa, Source: Authors, (2023) |

| Map 4.1. Map of Dar-Es-Salaam showing the Kinondoni Municipal Council, Source: URT, (2004) |

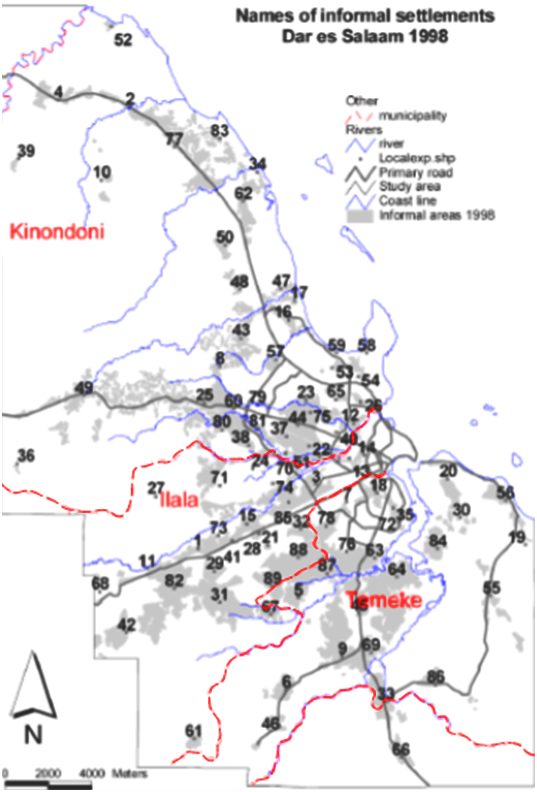

| Map 4.2. Informal (unplanned) settlements in Dar-Es-Salaam, with Mlalakuwa located on number 57, Source: [10] |

5. Results, Analysis and Discussion

- The collected data in this study were processed and analysed as per [16] writings, with the help of Statistical Software for Social Science (SPSS) for the data from semi–structured interview from household; and presented using maps, tables, figures, plates and numbers or explanations as the case may be. For example, observation was made where walking around and watching spaces between buildings and buildings themselves and to associate such with residents’ meanings as observed and reported. The below maps may summarize the closeness of buildings which identified lack of privacy that hardened spatial visibility among people.

| Map 4.3. The closeness of buildings in Mlalakuwa. Source: Authors (2023) |

b). Mainly men with a few populations of female most of them are office workers and business; they all move away to the university and city centre during the morning hours and come back during the evening hours.

b). Mainly men with a few populations of female most of them are office workers and business; they all move away to the university and city centre during the morning hours and come back during the evening hours. c). Most of the women around Mlalakuwa area stay back at home as housewives while few of them work out on the shops [saloon, stationaries, informal trading]. Most of them are always indoor and they come out mostly during the evening hours for business.

c). Most of the women around Mlalakuwa area stay back at home as housewives while few of them work out on the shops [saloon, stationaries, informal trading]. Most of them are always indoor and they come out mostly during the evening hours for business. d). They are few children and they play along the tributary roads and on the frontage of the home and few of them on the only one open space around the area. Most of their activities are during the day time.

d). They are few children and they play along the tributary roads and on the frontage of the home and few of them on the only one open space around the area. Most of their activities are during the day time. e). There are constant informal traders most of them been women who are residents of Mlalakua area and few non–residents who are male and they move along with their goods.

e). There are constant informal traders most of them been women who are residents of Mlalakua area and few non–residents who are male and they move along with their goods.

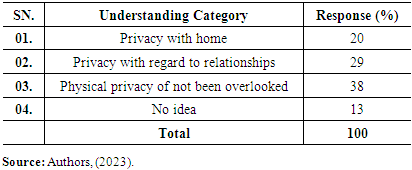

5.1. Residents’ Perception on Visual Privacy

- The study explored residents’ understanding on the concept of privacy as far as Mlalakuwa settlement is concerned. Variations in resident’s understanding was observed as their responses ranged from privacy with houses to “no idea” This variation may be a result of varying levels of education and exposure as indicated in Table 5.1. The results have revealed that (29%) out of 88 interviewed, understand residents’ privacy as privacy with regard to relationships such as neighbours. This means that absence of intrusion from frequent visits from neighbours defines privacy. Nevertheless (38%) of 88 interviewed, defined resident privacy as physical privacy of not been overlooked, while 20% of 88 interviewed, defined residents’ privacy as privacy within house. This category focuses on privacy that is found with the family; residents who argued in favour of this category mentioned that privacy should start from house. Their argument was based on having separate bedrooms, toilets, and isolated kitchen.

|

|

| Figure 5.1. Setting out of Mlalakuwa in aerial sketch up, Source: Authors (2023) |

| Figure 5.2. Malalakuwa Street, movements of bajaj, pedestrian and vehicles in a squeezed road, Source: Authors (2023) |

|

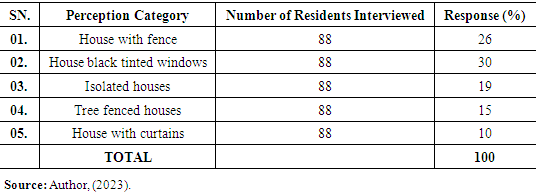

5.2. Achieving “Visual Privacy” in Housing Areas

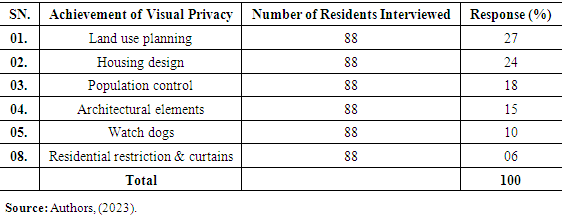

- According to [62], unwanted interaction could be controlled through "rules" (manners, avoidance, hierarchies, etc.), "psychological means" (internal withdrawal, dreaming, drugs, depersonalization etc.), "behavioural cues", structuring activities in "time" (so that particular individuals and groups do not meet), "spatial separation", and "physical devices" (walls, courts, doors, locks–architectural mechanisms which selectively control to filter information). In most cases, of course, multiple mechanisms are used but particular ones are stressed and they are combined in different ways. Results from the study have revealed that visual privacy can be achieved through land use planning, housing design, population control, and architectural elements, watch dogs as well as residential restrictions all put together. However, the control mechanisms were discussed according to their significance in achievement of visual privacy. Land use planning scored 27%, Housing design 24%, population control 18%, architectural elements 15%, Watchdogs 10% and residential restriction 6% (Table 5.7). Respondents who marked residential restrictions and curtains explained that in Mlalakuwa, there are residents that are not endowed by proper land use plan, population control, architectural elements and watch dogs yet they experience visual privacy only through strong restrictions they put against any kind of intrusion that make any intruder to fear get close to that house, again curtains complement their restrictions. Again, Altman theory focuses specifically on the mechanisms that enable people to attain their preferred level of privacy. The privacy mechanism includes verbal and para verbal behaviour (communication using body language or other signals), personal space, territory (ownership or possession of objects or places), and cultural mechanisms such as norms and customs. Because these privacy mechanisms represent different ways of being private, one can achieve the desired level of visual privacy in one way (for example, verbally by speaking), but not in another (for example, when one’s personal space is invaded).

|

5.2.1. Rules or Norms

- However, 18% of respondents insisted that privacy within is very significance and can hardly be achieved if one has a small house or a single room with many children or relatives. The respondents explained that indoor visual privacy can easily be achieved using some rules and norms which everybody have to abide. Regardless of how the house is designed because one can only put privacy rules in their housing areas and others adhere to that. For example, one respondent explained that:……“It is not allowed in this area to watch through windows of other resident’s room/house otherwise people will shout at you as a thief”……Within a house or room there are some norms or rules which are known to each member and they are all adhered to. Children or guest are not allowed to enter into the room without knocking the door and being allowed to enter in.

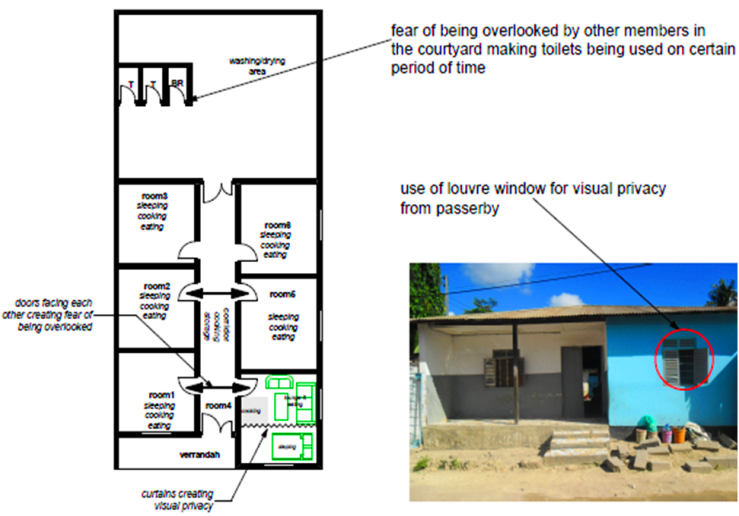

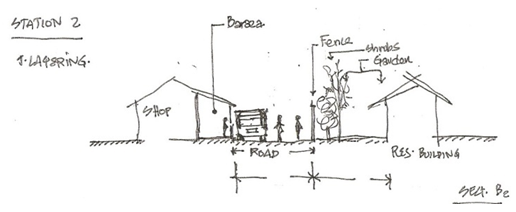

5.2.2. Housing Layout

- Findings revealed that; privacy within the house can be achieved by having a bed room for each person, separate toilets and kitchen. This was possible to residents with higher income within the settlements, (Refer Figure 5.3)

| Figure 5.3. A house having each activity in a separate room in Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

| Figure 5.4. A layout of door in one of the many Swahili houses in Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

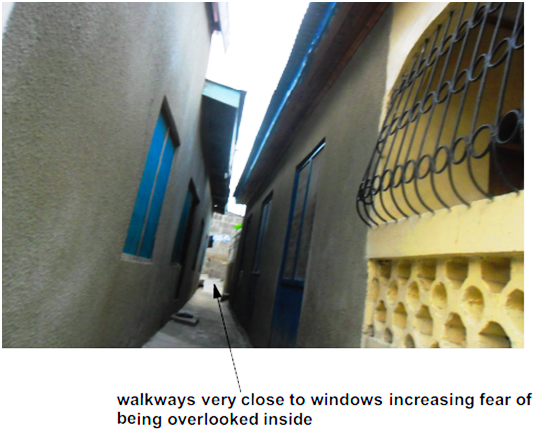

5.2.3. Layout of Windows or Doors

- It was observed that; the layout of openings has an impact on the visual privacy within a house. In Swahili house the visual privacy between one room and another was affected by the position of door. (Refer Figure 5.4). Residents in rooms having doors opposite to each other had some complain on their visual privacy. The location and position of windows and doors can hinder or promote privacy. The position of windows and doors in Swahili houses are located directly facing each other (in some cases) in a mirror image arrangement. Findings from the respondents living in rooms located directly facing each other indicate that position of their door affects their visual privacy as compared to those who live in rooms with doors not facing another. However, findings from case study show that despite its characteristic, majority of the respondents uses curtains as a means of accommodating visual privacy. Moreover, within Mlalakuwa settlement, windows which were facing one another between the neighbouring houses have serious visual privacy problems. (Refer Figure 5.5). The fear of being overseen from the passer–by or residents in the nearby rooms was high. Almost every window was within the eye level for the person to see inside.

| Figure 5.5. Windows facing each other along an alley within Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

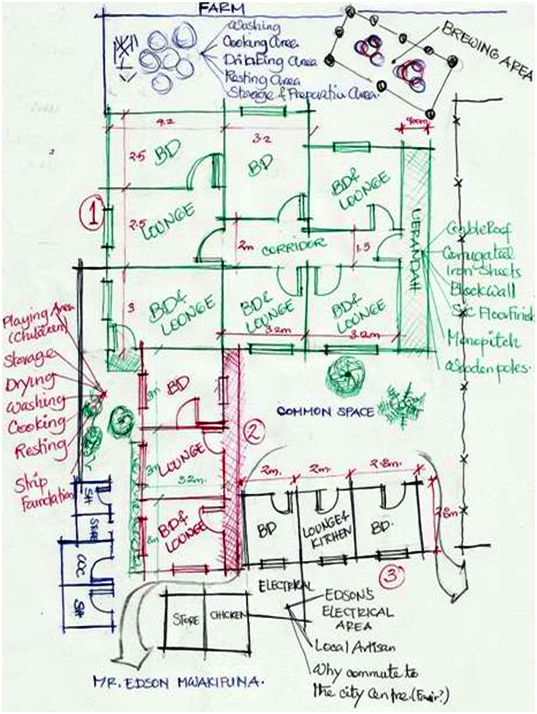

5.2.4. Space Organisation within the Site

| Figure 5.6. The location of various activities within a plot in Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

| Figure 5.7. The location of various activities within a plot in Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

5.2.5. Physical Elements

- Visual privacy was seen to be one of the reason people use physical elements especially when a house is either close to another house, a road, a path or a public space. In such cases some people may want to conduct their outdoor activities without being exposed to outsiders. This leads to screening or blocking direct vision from outsiders by constructing fences. (Refer Figure 5.8). Various types of fences have been used as one of the means of achieving the visual privacy in the housing areas. In Mlalakuwa housing area, various types of elements for visual privacy have been observed such as dense hedges, combination of wired fence and dense hedges, solid wall, louvered block wall and palm leaves.

| Figure 5.8. (Left) palm leaves fence, (Right) combination of wired and palm leaves fence within Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

| Figure 5.9. (Left) louvered block wall to enhance visual privacy, (Right) block wall as high up to 3m within Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2023) |

| Figure 5.10. (Left) a fence made of corrugated iron sheet, (Right) burnt brick wall fence and dense hedges fence on other side within Mlalakuwa area, Source: Author, (2023) |

|

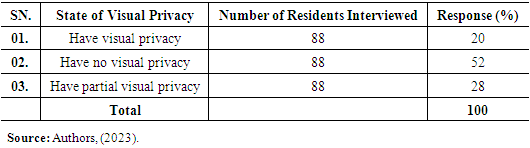

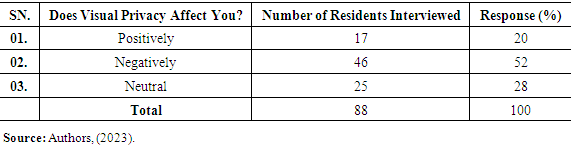

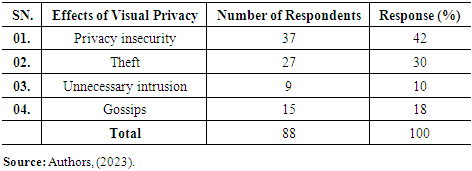

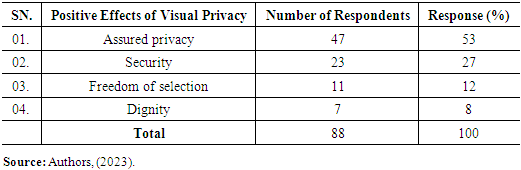

5.3. Effects of Visual Privacy in Housing Areas

- The findings have indicated that 52% of the respondents are affected by visual privacy negatively. This is because they had no visual privacy at all. 28% had neutral opinion on the effect of visual privacy in their lives whereas 20% admitted that visual privacy affects them positively. According to [5,32], protecting the tenant’s visual exposure in the urban environment can improve their personal feeling, their personal confidence, contributes to control their personal space and prevents penetration of undesirable disturbances. However, [31] argues that; being alone too often or for long period of time (isolation) and being with others too much for too long (crowding) are both undesirable states.

|

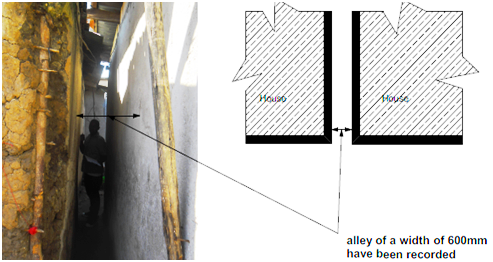

5.3.1. Fear of Doing Some Activities

- It was observed that; some residents were not comfortable doing some activities in spaces which are prone to be being overlooked.a) Cooking: some respondents were afraid cooking certain types of food outdoor/indoor courtyard due to inferiority complex of what they are cooking. This has made them cook indoor despite making the room uncomfortable. Only foods which are considered wealthy like meat, rice, and fish are being cooked in overlooked spaces. Foods like “dagaa” are hardly cooked on overlooked spaces because they are thought to be of low quality.b) Bedrooms: housing in informal settlement is done on incremental basis, [33]. Household responded that the need for visual privacy in their house was one of the reasons for increasing the number of bedrooms. Other reasons are economical, family increase, [33,41]. Overcrowding is common in the informal settlements houses where by a room becomes a house. In this case a room occupy people of different ages and sex, thus undermining the visual privacy. Visual privacy within a room is achieved by employing curtains to subdivide the spaces for various age groups and sex. Some activities are hardly done in the bedroom for instance changing of clothes is performed in bathrooms and toilets instead of bedroom due to fear of being overlooked. Many activities such as cooking, eating, sleeping, storage is done within a bedroom. Houses in informal settlements are built in close proximity. The distance between one house and another has been recorded as minimum as 600mm.

| Figure 5.11. housing proximity within Mlalakuwa area, Source: Authors, (2025) |

5.3.2. Exposure to Theft

- Issue of theft was said to be the number to negative impact on of visual privacy. This is because thieves take advantage of residential openness to spy on one’s possessions and plan how and when to get into the house in order to accomplish their mission. [3] on the study of crime defined ‘privacy’ as means towards achieving security of information contained within the home both of persons and of property and it means ‘something that gives or assures protection and safeguards against external influences infringing on the well–being of the home, the occupants and the properties therein’.

|

5.4. Impact and Implication of Residents “Visual Privacy” Mechanisms in Terms of Architecture Qualities, Series of Spaces, Planning and Urban Management

5.4.1. Architecture Qualities

5.4.1.1. Building Line

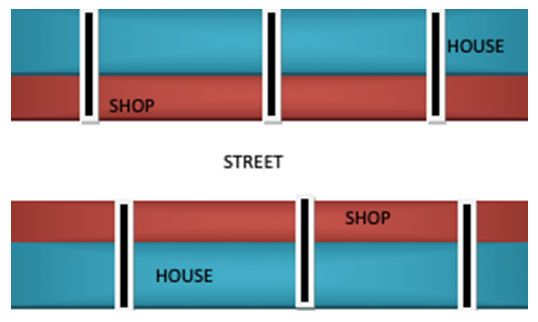

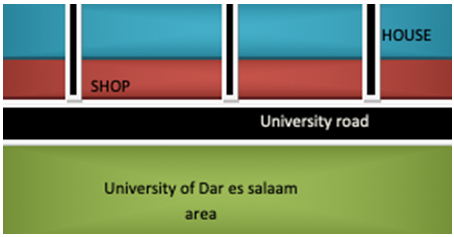

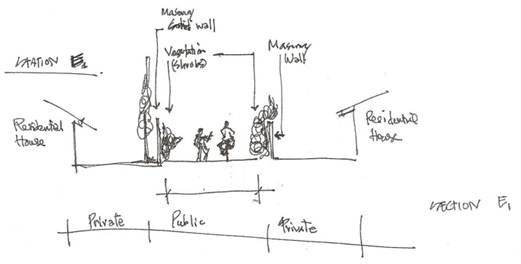

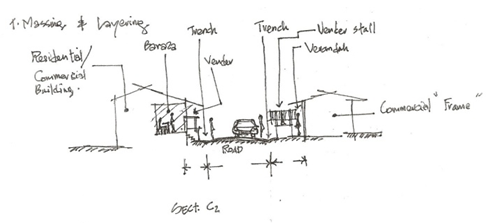

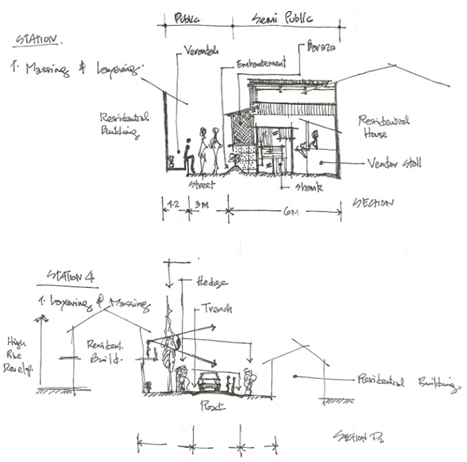

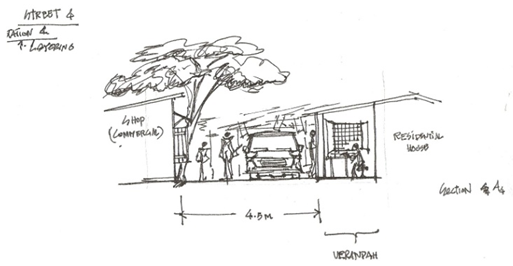

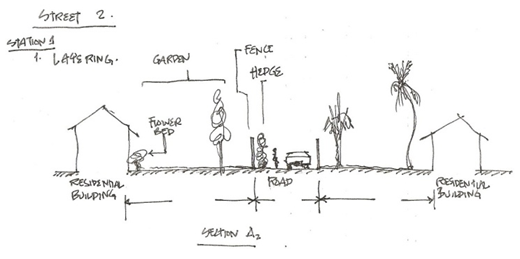

§ Meaning of spaces: – colours, meaning – visually, perceptual and physically interaction. Signage, decorations, activity such as commercial spaces.§ Security: – number of users, continuous flow of users, critical times of users and passer-by during morning and evening there is a great interaction.§ Fusion: – there is a high degree of fusion between indoor and outdoor spaces due to them being customers to retail and normal shops.§ Functionality: – close clarity of space in use, visual access used for display of commodities.§ Building line: – the building line defined by forming an irregular street wall.§ Territory: – there is clear definition of boundaries.

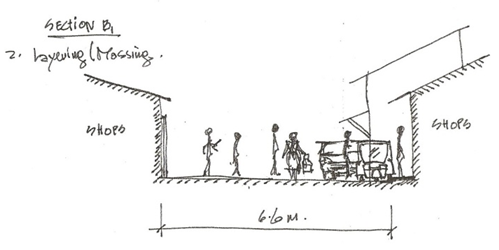

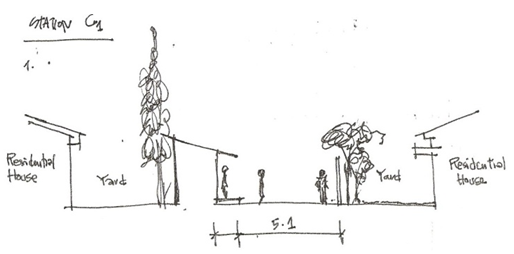

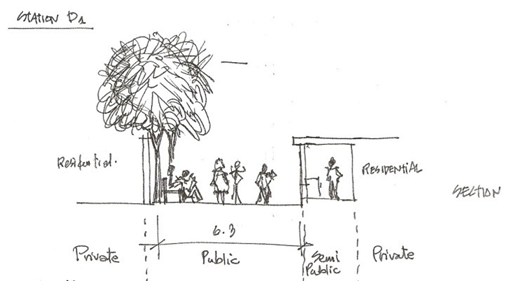

§ Meaning of spaces: – colours, meaning – visually, perceptual and physically interaction. Signage, decorations, activity such as commercial spaces.§ Security: – number of users, continuous flow of users, critical times of users and passer-by during morning and evening there is a great interaction.§ Fusion: – there is a high degree of fusion between indoor and outdoor spaces due to them being customers to retail and normal shops.§ Functionality: – close clarity of space in use, visual access used for display of commodities.§ Building line: – the building line defined by forming an irregular street wall.§ Territory: – there is clear definition of boundaries. § Layering or massing: – building – access road – building pattern defines the minimum distances and transitional thresholds from one space to another.§ Alternation of road width: – on wide part of the road allows space for parking, more interaction in terms as spaces of salutation on front “baraza”, facilitates delivery of goods, canopies that defines street facades as arcades. On the narrow part of the road acts as a street lounge, transition point, defines clearly changes in functions and enables more close interaction.§ Security: – high visual and perceptual security due to continuous flow of people.

§ Layering or massing: – building – access road – building pattern defines the minimum distances and transitional thresholds from one space to another.§ Alternation of road width: – on wide part of the road allows space for parking, more interaction in terms as spaces of salutation on front “baraza”, facilitates delivery of goods, canopies that defines street facades as arcades. On the narrow part of the road acts as a street lounge, transition point, defines clearly changes in functions and enables more close interaction.§ Security: – high visual and perceptual security due to continuous flow of people. § Residential or commercial: – shops are used to define plot boundary.§ Territory: – the territory is defined by fencing–building which is used as commercial space on the other side there is fencing wall.§ Fusion: – there is minimum fusion of spaces due to presence of physical and visual obstruction.

§ Residential or commercial: – shops are used to define plot boundary.§ Territory: – the territory is defined by fencing–building which is used as commercial space on the other side there is fencing wall.§ Fusion: – there is minimum fusion of spaces due to presence of physical and visual obstruction. § Functionality: – the street used as social space.§ Building line: – it is irregular and recessed from the street.§ Fluidity: – the street flows into household via narrow passages of about 1.2metre pedestrian street.§ Territory: – there is less diffused clarity of territorial demarcation.→ Building form, the space closure.→ Vegetation softens the street wall.