-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2023; 13(1): 12-22

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20231301.02

Received: Oct. 26, 2022; Accepted: Dec. 22, 2022; Published: Jan. 13, 2023

Rituals as the Dominant Factor in the Space Configuration of Traditional Persian Houses

Hengameh Fazeli1, Esmaeil Negarestan2

1Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2Faculty of Architecture & Design, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA

Correspondence to: Hengameh Fazeli, Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Based on several studies on traditional built space, it is evident that traditional houses were designed following well-established rules, patterns and rituals that believed to bring good luck and auspiciousness. These rituals were practiced in various stages of construction and have imposed specific patterns and decorations to architectural space. Comparative studies on rituals involved in the construction of dwellings in Indo-Aryan communities and case studies on traditional houses of Kashan, Iran, proves that rituals are one of the significant factors in determining the main elements of dwelling architecture in Persia. In this research the rituals connected to construction and their connection to architectural design and decorations of traditional Persian house have been investigated and introduced.

Keywords: Ritual Behavior, Persian Dwelling Architecture, Patterns of Traditional House, Symbolic Decorations

Cite this paper: Hengameh Fazeli, Esmaeil Negarestan, Rituals as the Dominant Factor in the Space Configuration of Traditional Persian Houses, Architecture Research, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 12-22. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20231301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction to Rituals

- Ritual in term means the performance of ceremonial acts due to the traditional commissions or sacerdotal decrees. It is also being used in modern times to address an established routine or a standard act. As ritual is a mode of behavior done by the people of different cultures in different ages, it is possible to view ritual as a way of understanding and describing the human nature. (Rapoport 1977)Ritual is basically described as a symbolic expression of individual as well as social beliefs which are based on sacred spiritual realities and the ultimate values of the community. The commonly usage of terms, latent and symbolic, often refer to the non-rational nature of ritualistic behaviors although they might be logical. Even some scholars such as Austin and Searle believe that semantic interpretations are insufficient in describing the ritual acts since they are performed to serve a function not just bear symbolic information. (Bell 1997)It is believed that ritualistic behavior was basically established as an imitation of how God and ancestors dealing with creation. Primitive man used to consider humanity as a concept which has a potentiality to become a super-human or a transcendent model. It means that unless he imitates the gods, mythical ancestors or cultural heroes, he/she does not consider himself/herself as a true human. Thus he/she accounted himself/herself responsible for preserving the nature as a manifestation of God. Ritual acts in this case were the acts of remembering this responsibility as a divine being and to make the built space consecrated by this divine presence. (Eliade & Trask 1968)The observation of rituals throughout history, apart from their symbolic significance, describes these ceremonial acts as an established set of rules and regulations practiced by the members of the community for generations. The creation of pre-industrial built space is one of the examples in which rituals were highly involved in determining the architectural patterns and the timing of construction stages. Traditional domestic architecture basically consists of three processes, first dealing with material construction of the house which includes selecting the proper site, preparing the site, positioning the house on the site, laying the foundation, building the structure and finally inhabiting it. Second process used to link these material constructions to the flow of cosmic time so that they would take place at auspicious times calculated by the household priest compatible with the horoscope of the owner. Thus, each stage of material construction used to begin when there is a harmonious temporal conjunction of the building process and the life-chart of the owner of the house. The third was connected to making the house an auspicious place for domestic activities in order to bring luck and prosperity to the inhabitants. This process involved creating a harmonious spatial conjunction between the house and the space on which it is built. This last process in fact involved the application of rituals. (Oliver 1997)In this way construction in traditional domestic architecture can be seen as a dual structure, both in physical and cultural dimensions. As the physical construction refers to a set of guidelines for finding a proper site, proper materials combined with the technical structural methods in building a durable shelter, the cultural or metaphysical aspect involved the processes through which the selected site became sacred by the application of a set of rituals done in an auspicious time. (Penner 2009)From all of these concepts, it is evident that traditional domestic architecture is more than an assemblage of building materials on a specific site and the building is considered as a physical as well as a spiritual body, not a mere thing or object. Thus, traditional house is a manifestation of ritual, cultural and social aspects and beliefs bind with the material techniques, crafts and economy. In all the traditional societies including Persia, besides the rules and regulations of construction, a well-established set of rituals were applied in the process of architecture, especially in creating a domestic built space, in order to make the selected place proper for inhabitation. These rituals therefore, as parts of architecture, have influenced the forms and patterns of our built space and the decorations applied on the main elements of buildings.

2. The Role of Rituals in the Creation of Architectural Space

- Following the theory of Nold Egenter, an architectural anthropologist, suggesting the restudy of past with the macro-micro concept to rediscover the meanings of potent dimensions that have been established in the construction of buildings from pre-human times, we must transform the concept of architecture as being merely a shelter to an arena where socio-cultural experiences take place. (Mugerauer 1994) This definition ascends the meaning of dwelling to a place where individuals or groups reside in physical, emotional, social and psychological levels while “creating a conceptual frame within which we conceive, or interpret, the domestic physical environment and notions for our socio-cultural and reproductive structures, a nearly total frame for our being that we, as members of cultural group, create.” (Benjamin 1997, 86) Therefore ‘dwelling’ seems to represent a multidimensional structure, physically and culturally. In physical environment it is commonly referred to individual as well as group transformations of nature which starts from the higher scales of nearby landscape to the lower scales of one’s own bed. In cultural level, dwelling is a social learned conceptual frame which represents human psychological transformations due to cultural values which occur in people’s consciousness about their environment and attach them emotionally to particular places. (Rapoport 1977)In this case architecture is both a container in which the creative expression of people’s behavior takes place and a frame within which their experience of culture from generation to generation occurs. (Benjamin 1997) This concept is far different from the modern interpretations of the term, considering architecture as a physical object which is continually responding to the physical mechanistic laws of nature, manifested in the famous phrase of Le Curbusier; “house as a machine.” (Alexander 2002), (King 2008), (Day 2004), (Olivier 1987) Therefore to have a better understanding of built space, and how certain forms and patterns have become significant in the field of architecture, we must study culture and ritual as one of its dominant forces.Basically, architecture is believed to be the fourth evolutionary phase originated from the patterns of previous cultural practices and ritual behaviors. (Bhattacharya 1974) The phases of human’s achievements dealing with architecture have been categorized by Nold Egenter, as followed:1. Subhuman architecture which is referred to the nests being built by three higher species of apes.2. Semantic architecture or nondomestic built elements used for ritual ceremonies which has a symbolic meaning and has established an architectural form.3. Domestic architecture as a result of two previous phases of constructive behavior which has ended in rise of an internal space.4. Settlement architecture, deriving from semantic architecture and the rituals of cyclical renewal which were crucial in preserving the narrative origins and social hierarchy. (Mugerauer 1994, 129)If we accept this categorization, the crucial role of rituals and the belief in sacred reality as the prior concepts in creating the domestic architecture will be undeniable. It is believed that rituals used to be performed during the stages of construction process in all traditional societies. Performing these rituals often took place before the construction of main elements of the house. (Bhattacharya 1974) Based on the documents it is possible to hypothesize that, the patterns of ritual behavior and the concepts involved in their performance, have imposed certain forms, geometries and decorative patterns on the creation of the main elements of the house which were involved in the application of rituals. It means that the main elements of the house and the excessive decorations which appear on them in traditional dwelling places are basically the result of the ritual behavior and the way they used to be performed.

3. Rituals of Ancient Persia

- Ancient Persia was basically located in the Iranian Plateau, in the center of famous civilizations of ancient times and served as a bridge between east and west. The name Iran (Previously known as Persia) has been derived from the term “Aryanam” which means the land of Aryans and is the name of the Indo-European, which is also known as Indo-Aryan or Indo-Iranian, people who were settled in the Plateau around the 11th century BC. (Bausani 1971)Aryans were in fact the first inhabitants of Persia, a group of who later migrated to India and transferred their culture and their architectural achievements to India. Migration of Aryans to India around 3500-1500 BC, pushed the Dravidian tribes who were the original inhabitants of the region to the south and the reason of common conflicts and disagreements between the Aryans and Dravidians of India might be due to this invasion. (Bindloss & Singh 2007) It is believed that the Vedas have been collected during the time when Aryans migrated to India and therefore it pictures the Aryan culture and their ritual practices. In fact, many hymns and sacred teachings of the Vedas are mixed with the beliefs of Aryans and based on their religious ideology and their gods. (Bindloss & Singh 2007) The earliest references from the Vedas and ancient sacred scripts reveal that the construction of dwellings was already associated with well-established rituals in Indo-Aryan culture, including Persian societies. In fact, not only some specific ritual acts were significant during the construction, certain forms and patterns of construction were also followed by the master builders and craftsmen which had symbolic or allegorical significance in Aryan culture. (Bhattacharya 1974) One of the examples of such set of symbolic patterns and principles involved in architectural constructions is gathered and introduced as Vastu Shastra guidelines. Most of the rituals held by Indo-Aryans were home-based and only the rich could afford the great public rituals lasting for several days in which the priests were participating. (Neusner 2009) Fire was the most important element in Aryan culture which is still a part of the rituals of India and the Zoroastrians of Persia. The importance of fire is denoted in ancient Persian poems as a purifying element. Water and earth were also significant elements used during the rituals. (Ardalan & Bakhtiar 1979) Through the teachings of Islam and its emphasis on water as the purifying element, later water gained more attention compared to fire in Persian societies. Although rituals of Aryans of India have been widely preserved and studied by scholars, the Persian rituals are rarely studied and introduced. However, since the rituals of India are the survivors of Indo-Aryan culture, it is believed that the same rituals used to be practiced by the Persians of pre-industrial era.Most of the studies of Persian rituals have only focused on the Yasna which is commonly regarded as the Zoroastrian ritual guide. In such ritual performances usually the old Avestan sacred texts were recited. Yasna is basically the name of the ceremony in which the entire sacred book is recited and the ritual acts are performed. Normally such ritual ceremony is performed in the morning with a presence of a well-trained priest who can recite the entire Yasna in about two hours. (Stausberg 2004)Following the Vedic model and based on the textual evidence, domestic rites used to play an unimportant role in the earliest years of Indo-Aryan communities; however, they might have become significant gradually and by the development of private life in the community. Basically, most of the domestic rituals revolve around the sacrifice offering rites, purification and thanks giving ceremonies in which the sacrificial fire is distinguished from the cooking fire and had to be kept burning “for the duration of the household.” (Bell 1992)Similarly, most of ancient Persian rituals which have been studied, involve many sacrificial offerings, purifications and consecration rituals. (Stausberg 2004) These rituals were involved in architectural construction following several stages, starting from the location finding to the last stage of house purification and settling in. The rituals should have been performed carefully and in specific timing suggested by the priest.Based on historical documents, studying the rituals involved in the construction of dwellings in Indo-Aryan culture, it is believed that most of the symbolic patterns present in traditional houses of Persia are basically originated from the application of rituals.

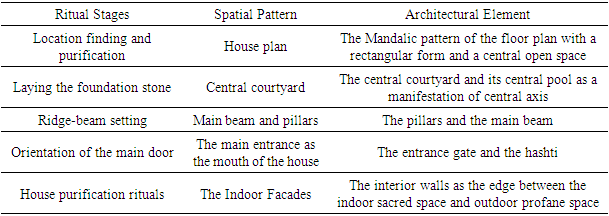

4. Rituals of Construction and the Creation of the Patterns of Traditional Persian House

- According to investigations of Paul Oliver and many participant scholars, rituals of dwelling construction in almost every culture, including the Indo-Aryans, can be categorized into five stages of location finding and purification, laying the foundation stone, ridge-beam setting, main door orientation and purification of the house before settling in. (Oliver 1997) All these rituals should be carefully performed in an auspicious timing, calculated by an astrologer or a priest. (Kumar 2005) The important issue about ritual is that primitive man found it to have a significant influence in his life, thus he started to apply them not only in religious ceremonies but also in every part of everyday life and therefore it is one of the important aspects of every culture, influencing the shape and characteristics of the built space.Basically, for primitive man rituals were one of the main parts of the building process. Thus, each stage of construction started with a ritual ceremony conducted in an auspicious time in which the architects, craftsmen and the householders should participate. These rituals are mainly applied as a reminder of the divine and the importance of maintaining harmony with nature. Thus, rituals indirectly ensure an orderly persuasion toward traditional norms of building construction. (Eliade & Trask 1968) Another reason for doing ritual acts especially before starting each stage of construction might be that the primitive man was not advanced in technological construction methods. Thus, during construction there would always be a risk of failure. So, if each stage would be finished accurately, he used to show his gratitude to gods and natural forces by performing rituals. (Frick 1997)Besides their spiritual significance, some of the rituals were methods of measuring physical consistency of soil, materials or structural methods. For example, rituals of digging a pit in the ground done by the Aryans of India and the Tibetans was a way to calculate soil’s load bearing capacity. (Oliver 1987) However even if these hypotheses are true, the main reason behind the application of rituals as a divine act to imitating God’s creation and maintaining harmony with nature will remain substantial. For example, in peasant communities building construction was considered a violence in which man interferes with the disciplined orders of nature which could corrupt the harmony of things. Thus, rituals were performed as an act of forgiveness to the natural elements injured or destructed in the process of building and to ask protective forces to guard the man-made structures. (Koeva 1997)As these rituals provide a sense of commitment, purity and humility towards God and nature, they serve an important part in the process of construction and ought to be followed strictly. (Chakrabarti 1997) (Stewart 1997)Each of these five stages of ritual performances is basically connected to one of the main elements of Persian house, present in almost all the traditional houses of Iran. Another influence of these rituals on architecture is the excessive use of decorations on the main elements of the house being used in performing these rituals.

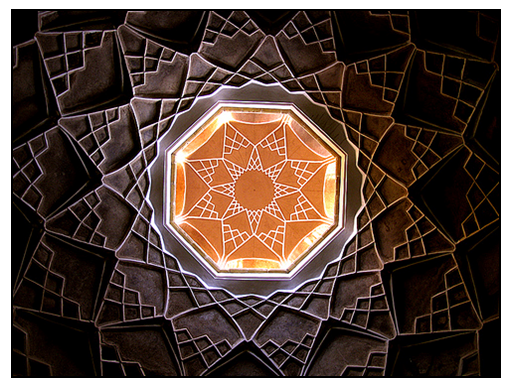

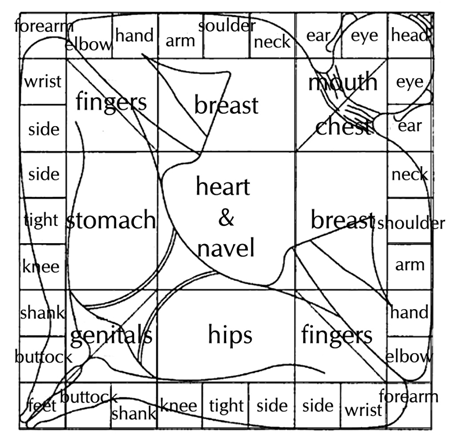

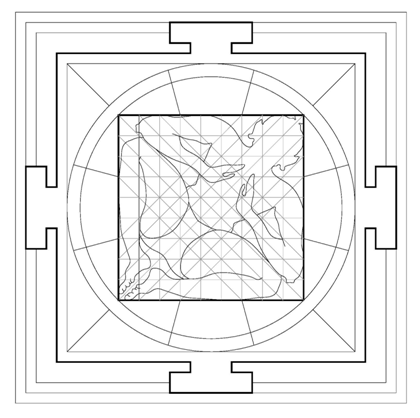

4.1. Ritual of Location Purification and the Creation of Mandala

- Selection of the right site for building was both physically and psychologically significant. The site should be naturally rich while having water resources and situated far from places with dirty energy fields such as graveyards or battle fields. (Bhattacharya 1974) Following these guidelines, most of the rich traditional houses of Persia have been located near Qanats (water resources) and holy places such as shrines. In fact, the existence of a holy shrine in the vicinity would definitely lead to the creation of residential district in that area. (Fatehi 2009), (Helli 2009)Following the ritual, the owner was ought to find two to four potential sites after visiting them for several times, where he feels good. He also had to visit the selected sites at night in order to examine the air currents. In this case feeling heat was considered as a bad sign revealing the existence of spirits while cold was associated with health. He then under the guidance of a spirit man or a priest used to choose one of the selected sites to start his housing construction. (Pecquet 1997) After the selection of the right site, many rituals were involved in purifying the selected plot and taking the possession of the site. These rituals of purification were applied to ensure that the supernatural forces of nature are working in favor of man and his family and the evil forces are exorcised. To eliminate the evil spirits from the profane selected site in order to make it a sacred property, many sacrifices were offered to these forces, whose peace was disturbed, as a compensation for leaving the place. Some other rituals might also symbolize the procreation of the house, like burying a certain amulet under the ground of every corner of the selected plot. (Frick 1997) In this case the four corners of the plot were considered significant spots which define the borders of the property. This stage in Persian societies deals with the concept of “mandala” which is basically a metaphysical energetic shield, which protects the house from the evil spirits and is also used during the religious practices. To protect the chosen plot from negative forces, the owner used to recite sacred mantras, which after Islam changed to 4 Suras from Quran, in each of the four corners of the house. In fact, the location finding was considered a magical act and dwelling in a certain plot, involved a careful selection of places on earth where man could stay in harmony with nature. Thus, there had to be a proper connection and harmony between the artificial manmade house and the mother earth. (Frick 1997) From the performance of this ritual the concept of mandala became important in traditional Persian architecture which proposes the sacred pattern for the location of the house and its plan. Mandala is basically a mathematical diagram which is metaphysically significant. This diagram is a rectangle consisting a complex set of squares and circles with spiritual and ritual essence that represent a graphical shape of what exists on a more subtle level of reality than what is usually perceived. (FIG.1)

| Figure 1. Mandala of Jnanadakini (Source: metmuseum.org/) |

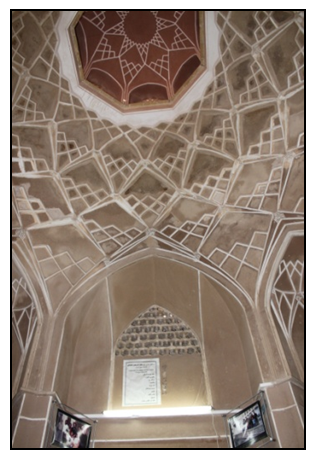

| Figure 2. Decorations of the roof of Abbasian traditional house which presents a perfect mandala, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 3. The application of mandala in the creation of Abbasian traditional house, Kashan (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 4. The analogy of house to human body in mandala of the house (Source: Fazeli based on Silverman 2007) |

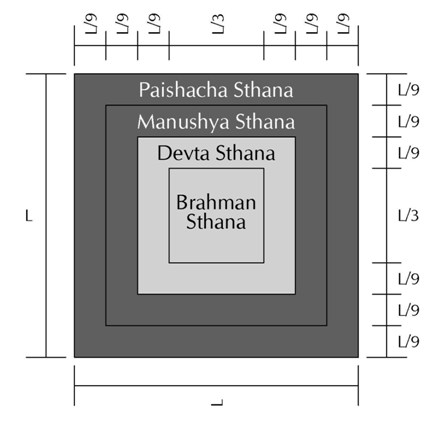

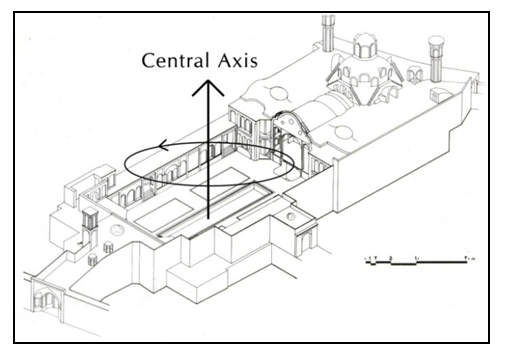

4.2. Laying the Foundation Stone and the Pattern of Central Courtyard

- Laying the foundation stone of the house is equal to giving birth to the house as a body; hence this ritual is supposed to be done at a potentially beneficial place. The place has been previously defined through the concept of mandala in the first ritual performance. In mandala, the center is basically the most important spot which refers to the concept of “unity in multiplicity and multiplicity in unity” in Persian culture. (Fatehi 2009) This central axis is very important in the creation of traditional Persian house around which the second ritual used to be performed.Creation of mandala starts from a central dot which is called bindu in Indian terminology. The central dot signifies the first seed. From the bindu as a central point or the place of the vertical axis, which was believed to be the axis of connecting human to God, the first circle was created signifying the dynamic consciousness. The outlying square in this case was a symbol of the physical world which was depicted with one gate in each of the four directions. (Goel 2000) (FIG.5) From the mandala, the concept of concentric squares is derived which defines the central point as the residence of the deity while the two outer squares are the residence areas of the human beings. (Kumar 2005) The model of central courtyard which was followed in the traditional dwelling prototypes of Persia and India is in fact based on the concept of mandala and its concentric squares. (FIG.6)

| Figure 5. Vastu Purusha Mandala, its geometrical form and names of the deities on it (Source: Fazeli based on Kumar 2005) |

| Figure 6. Open and built areas of the plan (Source: Fazeli based on Silverman 2007) |

| Figure 7. Diagram showing the distribution of spaces around the central axis (Source: Fazeli based on Moosavi, Soltan Zade 1996) |

4.3. Ridge-Beam Setting and the Importance of the Main Pillar & Hall

- In traditional domestic architecture, central pillar which the ridge-beam is associated with is very important. This ritual is considered as the ritual of initiation of the house. The ridge-beam around which the ritual setting was performed used to form the main part of the house and usually accompanied with symbolic decorations. (Olivier 1997) In Persian societies, the construction of the ridge-beam and the main pillars used to be accompanied with several sacrificial offerings and ceremonies.Several food and vegetables such as rice, fruits and plants used to be tied to the kingpost as an offering to the good spirits of the house. (Frick 1997) Besides, a ritualistic ceremony was conducted by the house owner and the craftsmen under the supervision of a priest, chanting sacred mantras which after Islam changed to verses from Quran. They also used to consecrate the unfinished house building by lighting incense or burning petals on a small charcoal stove which in Persian term is called ‘espand’. The same set of rituals used to be done in other traditional societies as well. For example, in Aceh region of Sumatra, two pillars which are connected by a horizontal beam to each other were raised while reciting verses of Quran. In this ritual ceremony, only if the construction takes place without a hitch, the house building could be continued. Later these two pillars and the horizontal beam would form the main room of the house. Throughout Southeast Asia, after accomplishing the beam work and before roofing started, a bunch of flowers would be fixed at one end of the ridge. Between the pillars, pieces of red cloths were also often tied which in Java includes three colors of red, white and black. (Dumarcay & Smithies 1987) Due to the performance of this ritual and the importance of the main pillar and the main room of the house, the main pillars and the main hall has become excessively decorated with stucco carvings and colorful paintings in traditional Persian houses. (FIG.8) The main hall is always the most decorated area in the whole complex in which the main pillars and the main beams are covered with spiritual symbolic patterns. (FIG.9) (FIG.10)

| Figure 8. Decorations of the main hall in Boroujerdiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 9. Decorations of the main beam of the main hall in Boroujerdiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 10. Decorations of the main pillars of the main hall in Boroujerdiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

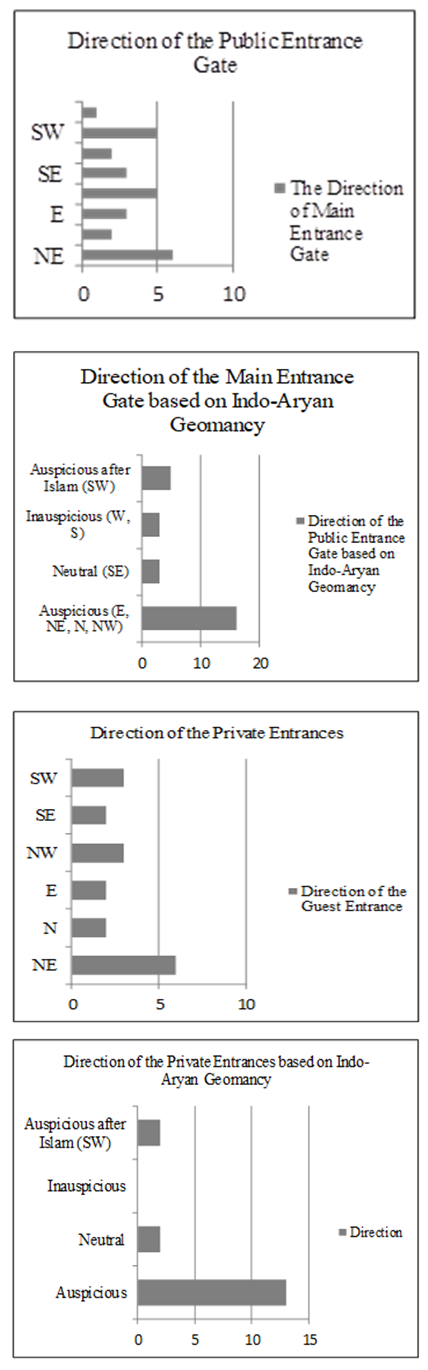

4.4. Main Door Setting and the Orientation of the Entrance Doors

- Besides the importance of the central ridge-beam, the setting and orientation of the entrance doors has been also an important part of dwelling architecture in traditional societies which suggests the idea of auspiciousness and inauspiciousness of certain directions. Traditionally it was believed that the doors should open towards one of the auspicious directions. While facing auspicious directions believed to bring prosperity, joy and blessings to the owner, facing the wrong one would create misery and pain. Since main doorway is a void in the exterior wall through which people enter the house or the world of the owner, it was always accompanied with several considerations. One of the most important issues in placing the main doorway was its orientation toward the eight directions. In primitive times, it was believed that every direction let a certain type of energy enter the house and therefore it was associated with a certain deity in all the cultures. For example, in Indian mythology, north was considered as the source of prosperity energy therefore it was auspicious. Its associated deity is Kuber, the god of wealth. (Kumar 2005)In ancient Persian beliefs, north, east, northeast and northwest were considered auspicious. After Islam, southwest which previously was one of the inauspicious directions became auspicious since it is the direction of the Kaaba. (Helli 2009) The manifestation of this ritual in traditional Persian houses, evident from the study of the houses of Kashan, is that a great portion of the houses have doors facing the auspicious directions, as displayed in the following charts.

| Charts |

| Figure 11. Dargah and the main entrance door of the Boroujerdiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 12. Hashti of the Tabatabayiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 13. Hashti of the Abbasian traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

4.5. House Purification Rituals and the Indoor Facade Decorations

- Traditionally nobody would be eager to dwell in a house until it became ritually purified, even if the construction was finished. It was believed that evil forces might have resided a house during the building process and they might harm the first inhabitants and bring misfortune. Thus, the house should be made sacred and be distinguished from the profane world before living. To combat the evil forces and eliminate them from the place, a set of rites was performed. (Frick 1997)The Idea behind such rituals was that the house should be purified from the negative forces and be filled with prosperity. This act was done by the use of sacrifice offerings, consecrating, lighting ‘espand’ and recitation of sacred verses.In Persian societies the rituals often involved offering a hen or a sheep to the demons or negative forces in compensation for leaving the place. Many sacred verses also were recited by the spirit man to exorcise the evil forces from the house. This ritual act of house purification is manifested in the Persian dwellings as excessive symbolic decorations of the indoor façade with the use of sacred figures and inscriptions, with the aim of raising the vibration and attracting positive forces (FIG.14) The subjects of these symbolic decorations were usually the patterns of sun, swastika, the tree of life, sacred birds such as peacock, sacred plants and also sacred inscriptions. (FIG.15) (FIG.16) (FIG.17) (FIG.18)

| Figure 14. The excessive decorations and the patterns of peacock and heavenly plants in the indoor façade of the Tabatabayiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 15. The excessive decorations and the patterns of swastika, chakra and the lotus flower in the indoor façade of the Boroujerdiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 16. The pattern of the tree of life in the indoor façade of the Tabatabayiha traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 17. The excessive decorations and the pattern of the sun and solar system in the indoor façade of the Abbasian traditional house, Kashan, Iran (Source: Fazeli 2010) |

| Figure 18. The pattern of two peacocks climbing the tree of life (Source: Cultural Heritage Organization, 2008) |

|

5. Conclusions

- Although it is wise to believe that many architectural elements have become important in architecture to serve a physical function or due to environmental criteria, i.e., entrance door to provide safety or security, one must also accept the fact that culture and ritual behavior have played significant roles in creation of patterns, symbols and decorations in traditional societies leading to current architecture. (Rapoport 1977), (Mugerauer 1994) Thus in this viewpoint, environment is not the most inspiring factor in dwelling architecture since ancient dwellings are not built in their most efficient configurations rather based on the symbolic values and the belief system of the culture where they have been erected. Based on case studies on traditional Persian houses, it is evident that such symbolic values and ritual behaviors, as the prior phases of creation of architectural spaces, have imposed certain patterns to architectural design which have becomes important elements of housing architecture in the later eras. As studies reveal, ritual is one of the dominant factors in determining the patterns and decorations of the Persian domestic architecture which used to be established based on cultural values and symbolic significance. Although the practice of rituals is not common in current era, as it used to be in traditional Persian societies, the patterns imposed by them are still active parts of dwelling architecture in Persia. As a conclusion, it seems that the study of rituals is crucial since many spatial organizations and ornamental features have been added to buildings as a consequence of ritual behavior and cultural beliefs. Studying them not only shed light on their meaning and significance, but also help the modern architects to use them more consciously rather than looking at them as mere aesthetical elements.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML