-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2022; 12(3): 55-63

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20221203.01

Received: Oct. 22, 2022; Accepted: Nov. 10, 2022; Published: Nov. 14, 2022

The Spiritual Side of Architecture – A Case Study on Traditional Persian House

Hengameh Fazeli1, Esmaeil Negarestan2

1Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2Faculty of Architecture & Design, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA

Correspondence to: Hengameh Fazeli, Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Traditionally, architecture was considered a sacred act, an act of becoming a co-creator with God. Therefore, the architect was expected to imitate the act of creation, following the laws and patterns present in nature, to create buildings that not only provide comfort but also stand in harmony with nature. This act of design and construction used to follow 2 levels: form and matter – referring to material and spiritual sides of every building. Traditional master builders, following this concept, were not only equipped with practical knowledge of building, but also the science of geomancy, astrology and the human system, that used to lead to creation of places which promoted health. Studying traditional Persian houses, such as houses of Kashan, which are believed to be the finest examples of traditional Persian architecture, the author believes spiritual aspects of architecture, besides the material aspects, are the reason behind their success in creating health-giving buildings that remain masterpieces, many centuries after their creation. In this research an attempt was made by the author, derived from the case studies, to identify these elements and introduce them as the spiritual side of architectural design. Using this pattern, the important elements of design and architecture can be identified and used by modern architects to create places that are considered health-giving, comfortable and pro-life.

Keywords: Architecture, Form, Matter, Theoretical art, Practical art, Health-giving architecture, Traditional Persian house

Cite this paper: Hengameh Fazeli, Esmaeil Negarestan, The Spiritual Side of Architecture – A Case Study on Traditional Persian House, Architecture Research, Vol. 12 No. 3, 2022, pp. 55-63. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20221203.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- For several centuries, architects built based on the macro-micro theory referring to the idea of a great saying “As Above, So Below.” This idea was further used to explain the fact that the same universal forces of nature influence the mechanism of living beings and, as present in all natural phenomena, it should also be present in all man-made structures. The belief in such theory has made most of the architectural efforts of the past to succeed in creating places in complete harmony with the surrounding environment and compatible with people’s lives, that remain timeless.Derived from the concept, one of the significant universal patterns leading to all creation is the division of form and matter in which form refers to the physical clothing or the quantitative aspects of objects while matter shapes the qualitative dimensions. (Salingaros & Mehaffy, 2006) Thus, for every architect, to succeed, both levels should be considered simultaneously through the designing process. In order to involve both concepts in the designing procedure, it is wise to first categorize the tools that the architect uses in every designing process, commonly known as the elements of design, into two levels of form and matter. In this way, and by introducing every element as a manifestation of an either spiritual or material reality, the architect will be able to consciously emphasize on both dimensions at the same time while none of the aspects will be left behind. (Akkach, 2005) As a result, if a structure is successful in displaying both of the aspects, it will respond to the universal forces effectively and will eventually achieve harmony with its surrounding environment.

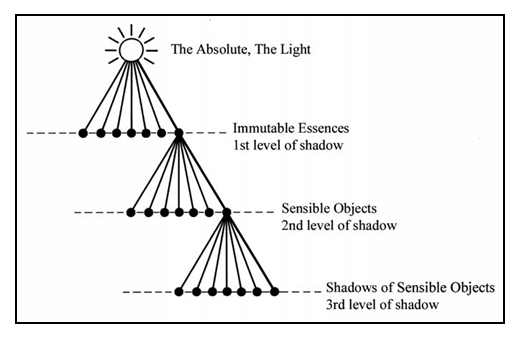

2. The Creation, the Architecture

- Every phenomenon is made up of an inner and outer meaning or aspect. Every single external entity is complemented by an inner truth or its inner nature. From another perspective, the outer side of things is the quantity of objects while their inner aspect is their actual quality. The actual quality of objects is in fact their divine nature and the outer visible side of them is the manifestation of the nature they represent. (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1979)Spiritual Ideologies have always emphasized the fact that the world is made up of both physical and spiritual realities, from visible and invisible entities. They often talk about the “seen” and the “unseen” worlds and about God as the knower of all, which to him belongs the unseen heavens and the seen earth. (Powell, 1882) The seen, is the physical world of natural phenomena that is discovered directly by the means of senses & perception, whereas the unseen is the world of spiritual phenomena that can only be touched through imagination and intuition. In order to improve the imagination faculty of the human beings, spirituality has used analogy and metaphor. Through these tools an ontological connection between the sensible and the abstract is traced and thus the human is given access to the abstract or the causal aspect of phenomena. In this process the language of symbols has been represented. (Day, 2004)Creating a relationship between these two aspects used to be the task of the creator, the traditional architect. The divine essence has to be made grosser and grosser in order to be manifested in the physical plane. What the creator performs is in fact the actual task of the Supreme Being breathing the essence of reality into physical modules. (Eliade & Trask, 1968) The Breath of the Compassionate is the substance in which flowers all form of material and spiritual being… Physical bodies are manifested in the material cosmos when the Breath penetrates the material substance which is the receptacle of the corporeal form. (Corbin 1969, 298)According to Akkach referring to Ibn al Arabi, the actual truth is similar to a source of light with objects around it creating shadows. The shadow is thus related to the object and also to the source of light. In other words the object can be a representative of a high grade of being or the imagination of the creator which exists more than the shadow; the ground on which the shadow falls to represent the archetypal essence of all possible things, or the field on which external realities manifest which is the physical world; the light that projects the shadow, represents the divine presence or the ultimate being and the shadow itself is the manifested object which extends to the external reality, or in other words the manifested object or the constructed entity. Ibn al Arabi further explains that the world is the “Zill” or “Absolute Shadow” as the lowest part of three levels of manifestation. The second level of shadows is actually the natural beings that project the immutable essences in embodied forms, and from these forms extend the third level of shadows which is the sensible shadow that project natural bodies on sensible ground. The first level of shadows however is non existing objects, the ones that have not even smelt the essence of existence. (Figure 1) (Akkach 2005)

| Figure 1. The hierarchy of shadows by Ibn al Arabi. (Akkach 2005, 34) |

| Figure 2. The pattern of two peacocks climbing the tree of life in Abbasi House, Kashan (Cultural Heritage Organization, 2008) |

3. Identity of Design

- According to Ikhwan, every manifested object whether man-made or God-made, necessarily comes from two fundamental components; form and matter. These components are actually two sets of effects commonly known as the elements of architecture: one set influencing the idea to manifest directly and the other indirectly. Matter addresses the very substance that admits form and form addresses every shape of variable motif, a substance is able to admit. Since different objects are created from similar matters, it is indeed the form which makes the differences. These two sets of elements can be regarded as the quantity and the quality of the act of creation. (Akkach 2005)Architecturally speaking, the first set of elements known as forms are in fact the same elements of geometry. They do not exist physically unless they have a matter to admit, thus they are abstract ideas and are categorized as the point, the line, the surface and the volume. The geometry itself is the quantitative aspect of architecture dealing with width, depth and height. They are the clothing of the universe or architecture yet without any quality, and thus influence the whole concept directly, and bring it one step into being since the physical world can understand it but not manifest it. Then there are the qualitative elements which however are connected to the whole concept, do not directly affect it. These are the matter elements of creation that give the cloth, its matter and bring the concept another step into the physical reality. Now the concept has materialized since it has a quality to be sensed by the physical world. Ikhwan further explains that the act of creation is a two parted act. The first part is practical art referring to the sensible product while the second is theoretical art referring to the knowledge that has led to such creation. Theoretical art in this case is the ability of the architect in receiving the symbols and transformable signs. He has gained it through constant purifications and meditations once becoming a master builder. Practical art on the other hand, is in fact bringing into being what there is in the creator’s mind and placing it in matter since every single object is a union of form and matter together. This part is creating it physically and giving it a divine identity. (Akkach 2005)Architecture in modern era, has advanced in one aspect, disregarding the other, which has led to creation of buildings that are comfortable physically but damaging health in the long run. (Day, 2004)In the original source everything is observed as a totality and all forms and matters are in fact related in a chain of relationships, thus nothing is independent. The shirt is a form with regard to the cloth, and the cloth is matter for the shirt; the cloth is a form with regard to the yarn, and the yarn is matter for the cloth; the yarn is a form with regard to the cotton, and the cotton is matter for the yarn; the cotton is a form with regard to the plant, and the plant is matter for the cotton; the plant is a form with regard to the “arkan” (elements), and the arkan are matter for the plant; the arkan are a form with regard to the [Absolute] Body, and the Body is matter for the arkan; the Body is a form with regard to the [Prime] Substance, and the Substance is matter for the Body. Likewise, the bread is a form with regard to the dough, and the dough is matter for the bread; the dough is a form with regard to the flour, and the flour is matter for the dough; the flour is a form with regard to the grain, and the grain is matter for the flour; the grain is a form with regard to the plant, and the plant is matter for the grain . . . This is the way in which form relates to matter and matter to form [in a sequential manner] until they terminate with the Prime Matter (al hayula al ula), which is nothing but the form of existence that includes neither quality nor quantity. (Akkach 2005, 37) This nothingness in Taoism is called “Kung” and in Hinduism, “Sunya.” (Master Choa Kok Sui, 2006)It is a simple Substance – without any kind of synthesis whatsoever – that is susceptible of all forms in a sequential order, as we showed, and not randomly. For instance, the cotton does not take on the form of the cloth until it has received the form of the yarn; and the yarn does not take on the form of the shirt until it has received the form of the cloth; likewise, the grain does not take on the form of the dough until it has received the form of the flour; and the flour does not take on the form of the bread until it has received the form of the dough. In this order matter takes on forms one after the other. This is how architecture should stay connected to the whole world, to the nature and to all sentient beings.With a broader perspective therefore, the created object is a manifestation of its identity which the architect gives to the building. This Identity comes from a primordial substance that overcomes all substantial differentiations and is known by the Sufis as “Hoo” or “Him.” This verbal similarity indeed points to the one nature of beings and introduces the actual identity of every being as an absolute quality of God. If the architect has not gained the theoretical art, there will be no identity for him/her to give to the building, since he/she has not experienced oneness. In this case there will be no transformation and the building should not be called architecture. On the other hand, if the architect hasn’t acquired the practicality of architecture, he/she is not able to transfer his/her theories, ideas and knowledge to the inhabitants of his creation; thus, quite similarly there is no transformation and no architecture. (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1979)In this way, the traditional architecture is composed of its physical existence with its symbolic representations and ornamentations that give it its identity, connecting it to the divine. An example of traditional Persian house with its symbolism will be presented in future sections.

4. The Language of Symbols

- Symbolic expression has always been a significant part of traditional architecture, especially as a attempt to portray spiritual side of things.“Religious understanding of spiritual realities hinges on the efficacy of such analogies, and symbolic reasoning relies on and promotes similar modes of thinking. In constructing ties between the divine and human modes of existence, analogical reasoning operates in the paradoxical space that lies in between the contrasting dimensions of analogy.” (Akkach, 2005, p. 30)According to Ibn al Arabi the use of symbols becomes necessary in two circumstances. One is when the communicators are so far apart from each other that they cannot hear each other’s voices; they are however able to see the movements of one another. In this case one acts in a manner so that the other can understand his message through the signs and symbols represented by him. The other is when the communicants are close but because of a limitation of the listener, such as deafness, the verbal message is not conveyed; thus, the language of symbols is the solution for this communication. (Akkach, 2005)In the case of architecture and through the use of symbols, the divine realities and presence can be portrayed. Whether the meaning of symbols is understood by the observers or not, the effect of them on the building could be experienced. However, if the observer is also equipped with proper knowledge, the effect can be magnified and transcend his/her experience. Thus, the importance of the symbols is not because of themselves but for what their message and effect is on the inhabitants. Symbols are connections that manifest as sensible aspects of meta-physical truths. Thus, they are not created by human beings as he/she is the listener, yet they can transform him/her. (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1979) Symbols reflect the absolute light, the source or the origin. Symbols are indeed created by the Divine to uplift human beings for the sake of evolution, like nature. Nature is full of divine symbols, for the one who can see the signs and read them; they can be transformed by its message. (Master Choa Kok Sui, 2006)The architect in this case, is the carrier of the divine symbol and thus he must be capable of receiving them. That is why the traditional architects and master builders were not only equipped with construction knowledge but also sed to study geomancy, astrology, meditation and spiritual sciences.The language of symbols are present in every element of design, as the spiritual side of architecture.

5. Elements of Design

- The elements of designing are in fact the major themes in any common architectural creation; with the application of these elements a specific creation will be called architecture since a unique action is done and an identity is given to it. In other words, these elements are in fact the tools which the architect uses in order to bring his intuitive understanding, his imagination or his inner experiences into being. The forthcoming categorization describes the characteristics of these elements which are related to one of the two dimensions of form and matter; or one of the two acts of theoretical art and practical art.

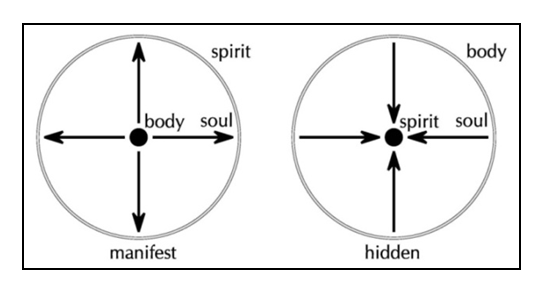

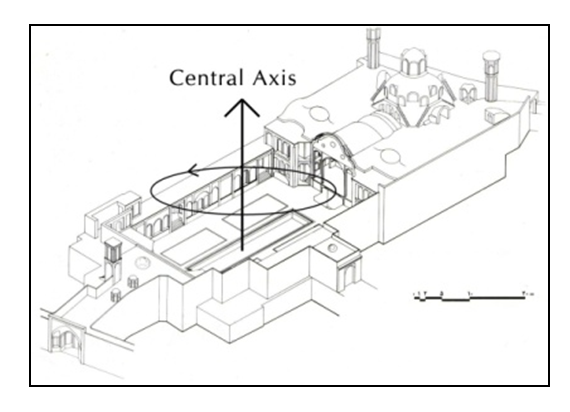

5.1. Space

- Space is a three dimensioned feature of quantity. In a worldly manner space consists of six directions of north, south, east, west, up and down as a primary coordinate system where every single object is situated. Every object or body is also an extension of length, breadth and depth; thus, there is no particular difference between space and a corporeal object. This body is however raw and without a substance since its quantity is only distinguished and is regarded only as an empty being or an abstract idea with numbers. (Descartes, Cottingham and Stoothoff 1935) It does not have a tangible existence, yet exists in the consciousness of its beholder who imagines boundaries and marks it as a place. The concept of place in fact rises when there is an actual object which is being held contained. (Figure 3)

| Figure 3. The importance of the central axis in traditional Persian teachings |

| Figure 4. The pattern of flow of cosmic energy in dwellings (Kumar, 2005, p. 38) |

| Figure 5. Diagram showing the distribution of spaces around the central axis in Boroujerdi House, Kashan (Author based on (Moosavi Rozati & Soltan Zade, 1996, p. 35)) |

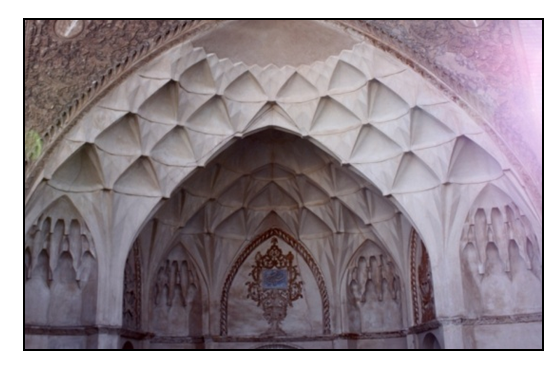

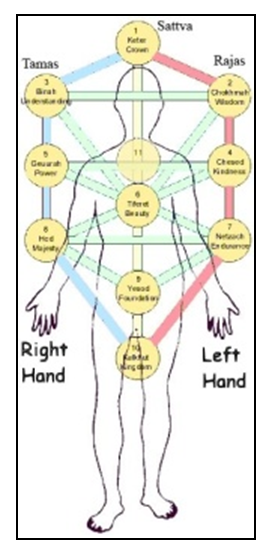

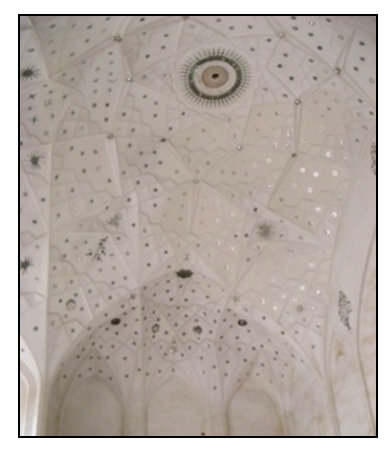

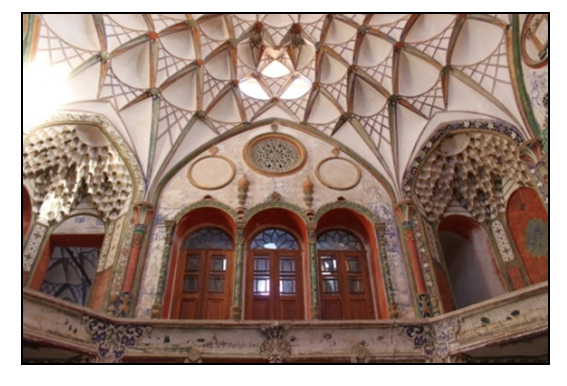

5.2. Surface

- Within the hierarchy of spatial definitions, surface stands after the three-dimensional space. Surface can physically delimit shapes and thus is capable of making spaces, yet it is not present in the physical world. In fact, physically speaking, the point, line and surface do not exist and whatever there is as an object it is introduced as in volumes. Regarding this argument however surfaces carry a symbolic dimension in the architectural world. Within the surface patterns and shapes link places together and portrait desired stories and secrets. Human being has always wished to express his/her ultimate love for the creator and through patterns, designs and colour he/she has managed to do so. According to Ardalan and Bakhtiar, surface is represented symbolically in three areas; the floor, the wall and the roof. The floor is the horizontal extension of architecture that symbolizes the earth; the wall symbolizes the third dimension of space where the vertical direction meets the ontological axis; and the roof symbolizes the heavenly aspects where the spirit reaches its zenith and takes his journey back home. (Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1979) (Figures 6-9)

| Figure 6. The symbolic decorations applied on the wall and ceiling of hashti in Boroujerdi House, Kashan (Fazeli, 2010) |

| Figure 7. Symbolic pattern of the tree of life in the portal of the Boroujerdi House, Kashan (Fazeli, 2010) |

| Figure 8. The symbol of tree of life and the chakras (kimgraaemunch.files.wordpress.com) |

| Figure 9. Pattern of swastika on the floor of hashti in Boroujerdi House, Kashan (Fazeli, 2010) |

5.3. Time

- The second group of variables deal with the qualitative aspect of the creation in comparison to the geometrical quantities of it. These variables do not directly influence the creation yet they cause influences on the manifested form. One of the most important aspects of quality in architecture is the time of construction. In this definition time actually does not refer to duration, yet it points to an exact time when construction has to be carried out. The specific moments and the effect they bring are calculated through some precise observations on the position and relation of heavenly bodies or planets which is known as the science of astrology. Astrology is known as “Jyotish” in the Indian tradition which literally means “The Light of God.” It represents the eye in the Vedic body that is achieved by the ones who have gained the qualities of the divine. The heavenly bodies cause great influences on many aspects of life on earth. The fundamental principle of astrology is that everything in the universe influences other beings and in turn is influenced by them. In fact, astrology describes that the smallest being in the universe is a subject of the same process as the largest. Thus, there is a natural resonance between the evolving universe and the human soul. Whatever is created in a particular moment thus has the qualities of that particular moment. Symbolical representations to the importance of astrology and the auspiciousness of construction can be found in the decorations of traditional Persian houses. The sun, the stars, the galaxy and the solar system are common patterns of decoration in interior space and the courtyard. Even the system of colours has been taken from the knowledge of astrology. For example, in a hall in Abbasi House, mirror-work is used (Figure 10), to resemble the starry night and the solar system which is rooted in the beliefs of Indo-Aryans dealing with astrology and the influences of planets on the life of the human beings on earth. The pattern of the sun is also used in the decorations of the facades around its courtyard (Figure 11). (Arzandeh, 2009)

| Figure 10. Mirror-work in Abbasi house, Kashan, depicting the solar system (Fazeli, 2010) |

| Figure 11. The wall decorations, depicting sun and the circuits of the solar system, Abbasi House, Kashan (Cultural Heritage Organization, 2008) |

5.4. Colour

- The physical world is pure darkness, a shadow which has not shown itself until and unless the light is presented. The world is born in light and now colour springs from this colourless reality. The world of colours thus has been introduced as the manifested world of multiplicity or the concept of physical life; and just as the being of colour is totally dependent on the being of light, all are a reflection of the One.The difficulty of knowing the One, is therefore due to brightness; He is so bright that human beings' hearts have not the strength to perceive it. There is nothing brighter than the sun, for through it all things manifest yet if the sun did not go down by night, or if it were not veiled by reason of the shadow, no one would realize that there is such a thing as light on the face of the earth. Seeing nothing but colours, they would say that nothing more exists. However, they have realized that light is a thing outside colours, the colours becoming manifest through it; they have comprehended light through its opposite. . . He is hidden by His very brightness. (Ardalan 1974, 169)Colours are divided in ranges according to their manifested values. Esoteric approaches to the varieties of colours have been developed in almost all traditional cultures including Persia. “Haft Rang” or “Seven Colours” is a system of art developed in the Persian lands which was developed according to the seven stages of spiritual development and the seven heavenly bodies, and was symbolized by the seven colours of rainbow. These colours are simultaneously related to numbers and numerological qualities as well, like the seven visible planets, the seven days of the week, the seven metals, the seven climates, the seven notes of music, the seven major energy centres of the human body and so on. These seven colours are: night-blue, turquoise, white, black, green, yellow and red; (Barry, 1996) (Ardalan, 1974)“Persian usage imposed this traditional name of the “Seven Colours” or Haft Rang, because the number seven was held to correspond to that of the sanctified Seven Heavenly Bodies of determining importance so identified in all the calendars stemming from Ancient Mesopotamian astronomy: Saturn, the Sun, the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter and Venus.’ (Barry, 1996, p. 33)The colours in this way were used base on the effect they produce of human system. Warmer colours were used mostly in the halls, gathering places and family areas, where activeness, dynamism and joy were required while cooler colours were used in meditation rooms, religious halls, bedrooms and places that required calmness and peace. (Figures 12 & 13)

| Figure 12. Example of using warmer colours in the gathering hall of Boroujerdi House, Kashan (Fazeli, 2010) |

| Figure 13. Example of using cooler colours colours in the sardāb (basement), being used in summer time (Fazeli, 2010) |

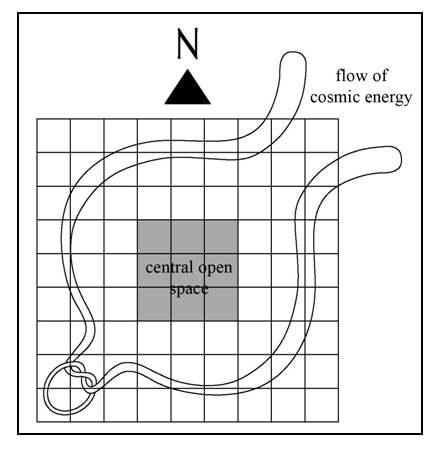

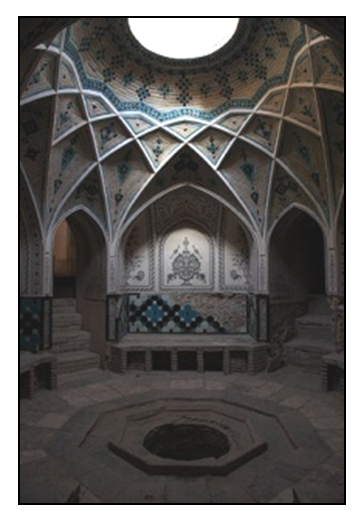

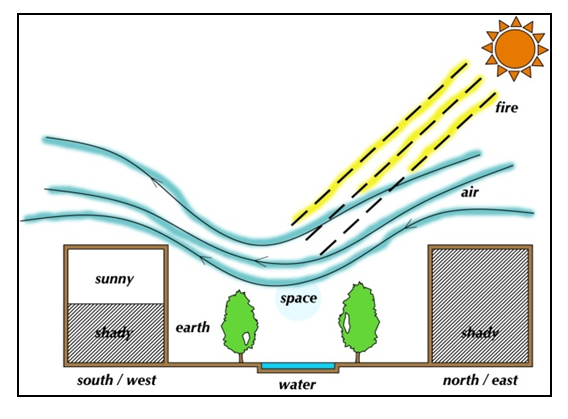

5.5. Matter

- The matter of artificial work is objects (jism) in which an artist works his/her art, such as the timber for carpenters, the iron for ironsmiths, earth and water for builders, the yarn for weavers, and the flour for bakers. Accordingly, it is necessary for every artist to have a “body” to apply his/her art on. This body is the matter of artistic work… Natural matter is the four elements (arkan). All that is found in the sublunary sphere, the animals, plants, and minerals, come from the elements and by corruption return to them. The active nature responsible for this process is one of the forces of the celestial Universal Soul… Universal Matter is the Absolute Body, from which is drawn the entire world, that is, the celestial spheres, the stars, the elements, and all beings. These are all bodies whose diversity derives from their diverse forms. As for Prime Matter, it is a simple, intelligible substance that cannot be sensed, for it is the form of being proper. It is the Original Identity (al huwiyya). (Akkach 2005, 38)Form manifests with matter, it brings bodies into being and begins its physical existence. All bodies on the physical world are made from matter. All bodies are in fact comprised of the four bases of fire, air, water and earth which are combined in different amounts. The four are the fundamental conditions of matter and four modes of materializing qualities. The fifth is this case refers to ether or the cosmic energy. The central courtyard in traditional Persian house is the manifestation of these five elements. The central open space of the courtyard is designed to absorb the invisible cosmic energies (or ether), and also to allow fresh air inside the house. (Figure 14)

| Figure 14. Diagram showing the distribution of five elements in the central courtyard |

5.6. Order

- There is a deep connection between the divine act of creation and the human act of designing which indeed lies in the “Order” of the universe; a threat that ties together whatever there is in any dimension. This is when there is no time between will and creation since it is a divine act that breaths into beings; thus, the architect similarly has to breathe the identity into his buildings. When the building has this fire, it becomes part of the nature, since their identity is now from a single source. (Akkach, 2005) Exactly like the waves of an ocean or the movements of a grass, the building lives as a part of nature, standing in harmony with all creations. Its features are ordered by an endless play of motion and variety, exactly like a tree with its various leaves and branches. This is the quality which represents itself as a wonderful act of beauty with a unique sense of order, that gives the building its timelessness. What creates nature is actually a series of patterns. Each pattern or feature is a unique solution responding to a system of forces in the universe. (Alexander, 1979) Yet the forces are never the same. These created patterns and features are repeated to create architecture as they are to create nature. What makes these unlived patterns become a brilliant masterpiece in nature is the breath of God. It is indeed the identity or order which is given to these unlimited objects that makes them follow the invisible rules of beauty. The role of the architect is indeed the same in bringing the quality without the name or this breath of God. Thus, the character of nature cannot arise within the buildings unless the architect has understood the concept of creation. (Alexander 1979)

6. Conclusions

- As a conclusion, and as a result of theoretical research on the concepts and properties of traditional architecture and the case studies on the houses of Kashan, the elements of design can be categorized as space, surface, time, colour, matter and order, in which symbolic language is used as a representation of spiritual side of existence.These elements, based on how they are used by the architects, create several patterns, each responding to specific universal forces. Such fine patterns, or small features, are repeated to create larger patterns or systems known as architecture. The role of the architect in this way is to use the elements correctly to create buildings that not only provide physical comfort, but also infuse life-giving qualities. When buildings are created considering both high and low architecture (material and spiritual), they stand in harmony with nature, become timeless and pro-life.Traditional houses of Kashan present examples of buildings that not only answer to human needs by supplying a comfortable space to live in, but also imitating the act of creation in nature, provide the emotional, mental and spiritual needs of its inhabitants.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML