-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2020; 10(3): 75-84

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20201003.02

Post-Pandemic Cities - The Impact of COVID-19 on Cities and Urban Design

Sara Eltarabily , Dalia Elgheznawy

Assistant Professor, Architecture and Urban Planning Department, Faculty of Engineering, Port-Said University, Port Said, Egypt

Correspondence to: Sara Eltarabily , Assistant Professor, Architecture and Urban Planning Department, Faculty of Engineering, Port-Said University, Port Said, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Throughout history, pandemics have always shaped cities; many health issues have been reflected on architecture and urban planning. Today, the world faces a public health crisis of COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps the worst in more than a century, which resulted in the emergence of many challenges for cities to face this epidemic. But what will happen after the pandemic? Will the global epidemic affect reshaping cities and urban areas? The rise in the number of people infected with Coronavirus and the increasing number of deaths may result in a review of the usual city-design strategies. The aim of the study is a literary review to study the relationship between the impacts of the epidemic on the city and urban design, historically and currently. It proposes new recommendations in the field of healthy urban design, In addition to studying the most important strategies of the cities that have proven effectiveness in dealing with this global epidemic to guide future research.

Keywords: Pandemics, COVID-19, Urban design, Smart cities, Healthy Cities

Cite this paper: Sara Eltarabily , Dalia Elgheznawy , Post-Pandemic Cities - The Impact of COVID-19 on Cities and Urban Design, Architecture Research, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 75-84. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20201003.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The world is now facing unprecedented restrictions; many of the world's population were required to remain in their homes. As for the recommendations announced by WHO to the public; the quarantine, social distancing, and self-isolation have become one of the essential strategies to reduce the spread of this global epidemic [1,2]. These procedures not only contradict the desire of individuals for social interaction, but also conflict with the way of (cities, parks, squares, subways, and shared spaces, city streets) are designed [3]. Although the interconnection between cities is a major source of social and economic progress, it also helped the spread of COVID-19 disease. So, it would raise many questions by designers and planners about the difference between the trend in design towards increasing social relations between individuals [4], and the need to separate the population during the current situation [5].We are now amid unprecedented measures in the use of public places around the world. Despite these restrictions, it’s a good opportunity to save cities from using cars. As the priority now under this pandemic is to give priority to pedestrians and cyclists and design healthy buildings that would change cities for the better. Whereas, according to the World Health Organization, “healthy cities and the city planning process are background papers supporting the work of the World Health Organization” [6]. But from urban planning and health, the current urban developments have not been very successful [7]. Therefore, it is necessary to stress the importance to go to the designs of cities and the urban environment in a way that provides a healthy environment for individuals. The interrelationship between city elements such as (the buildings, streets, public parks, and infrastructure of cities) significantly affects the quality and effectiveness of life for individuals in cities [8].The research dealt with the impact of the epidemic on the design of cities and urban areas historically, and the challenges faced by cities in the current crisis that were derived from the view of individuals' health. The research directs the viewpoint of designers and planners towards the relationship between urban design and health. The effectiveness of functional cities in managing the current crisis is discussed. It comes up with the most important strategies of these cities to help in redesigning cities when facing any coming crises.

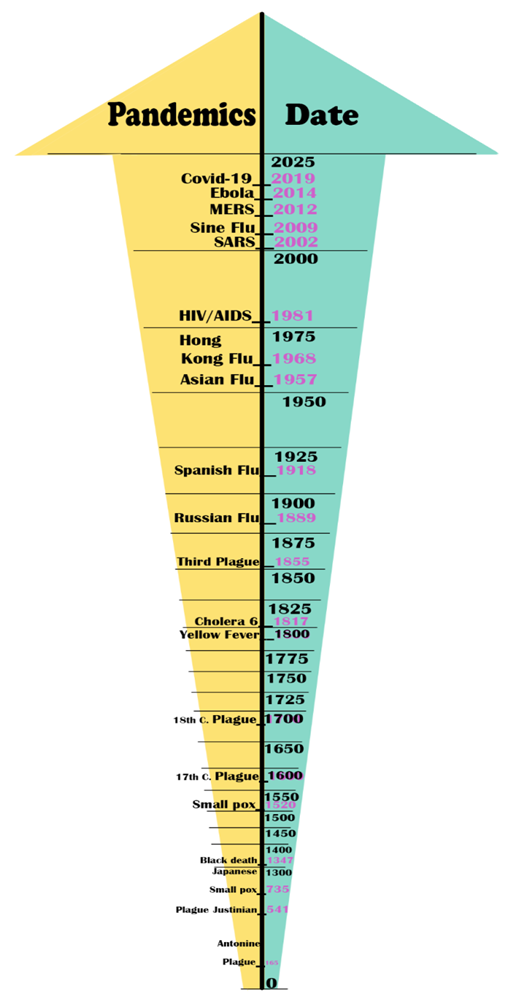

2. Historical Pandemics and the Transformation of City’s Shape

- Coronavirus isn’t the world's first pandemic, there have been other pandemics that have hit the world and ended the lives of millions [9]; see Figure 1, which not only affected the health field but also left urban impacts and economic consequences. A pandemic is the worst scenario which happens when an epidemic outbreaks beyond the country’s borders. When epidemics especially respiratory ones emerge, precautionary measures emphasize the necessity of isolation, and closure of public spaces. Also, it turns the image of cities and public spaces into empty environments, but mostly after the end of the crisis; it requires a change in the city’s shape to integrate between community health practices and social thinking into urban design.

| Figure 1. History of deadliest pandemics [Source: by the authors, adapted from [9]] |

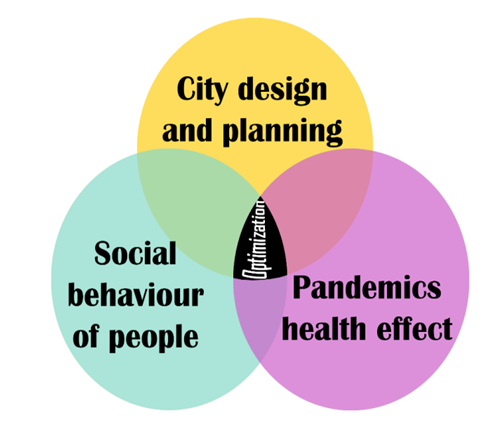

3. Integration of the Health Perspective in the City Regarding Pandemics

- Based on both historical and contemporary views, this point will address city design and urban planning such as (cities density, streets design, public transport, public spaces, parks and green areas, and building design) as it pertains to the health of population during the epidemic, when cities face major risks, with increasing numbers of positive cases and deaths related to the size of cities and population density [20]. COVID-19 pandemic may be a chance to optimize cities by integrating the social behaviour at a pandemic time through health perspective in planning and design; see Figure 2. For example; the idea of introducing a health perspective into the design of public spaces as a consequence of the pandemic is not new [21], but it needs to be reactivated [22]. Social behavior and citizen's awareness are considered an important factor in dealing with this pandemic [23].

| Figure 2. Integration of health, social effects in the city [Source: by the authors] |

3.1. Cities Density

- City and urban design may need to be revised from a population density point of view, which is one of the most basic factors affecting the spread of an epidemic; In other words, the greater the population density, the greater the risk of infection [24]. So, cities need to review appropriate planning not only to achieve social justice but also to face epidemics in a sustained way.As for density, which led to the necessity of taking many precautions to confront the global epidemic, it was necessary to refer to history and the benefits from lessons of the past in facing such a crisis [18]. It’s noteworthy that the first attempts of urban planners historically to prevent the spread of cholera in Paris in 1850 were by reducing the high population density in some cities. As happened in poor cholera infected neighborhoods by Baron, the streets and parks were widened, and sewage systems were established [25,26].Regarding WHO’ regulations that indicate avoiding crowding and closing places of assembly, as is the case in many countries [2], which closed cafes, restaurants, theatres, shopping malls, green spaces, and schools. In addition to the precautionary measures for the use of transport which are active places and points where the virus can spread. Although, closing public spaces was an effective action; basically state’ orders to stop gathering, isolate, and quarantine, made a significant effect on cities that reacted early [23], but especially in countries like Egypt; that can’t fully lockdown for economic, social reasons.. etc., so decision-makers should find ways to push populations to less dense cities instead of living overcrowded in Nile valley and delta.There was another urban planning suggestion by Anne Hidalgo; Paris mayor in her recent campaign who has proposed the city’s decentralizing and deconstructing policy. That can reduce extreme density, and promote the concept of walkability in each neighborhood, in which containing homes, jobs, facilities, stores, etc. [27]. According to a study by Birch 2020 [19,28]; if neighbourhoods are changed to be more walkable, and placed services and jobs in those communities; cities can be able to mitigate the intense congestion and crowding that you have in various systems such as public transit".Anthropologically, walking isn’t only a kind of human movement, but also a culture and social practice that can promote physical activity and affect the residents' health besides increasing the value of urban spaces. For example, integrating walkability in neighbourhoods within Washington as an environmental feature; can increase demand and value of facilities like residential, offices, schools, etc. [29,30]. Numerous other research demonstrated the importance of incorporating the walkability index in the urban environment and its beneficial effects on health, economic, and other aspects [31-34].

3.2. Streets Design

- The 21st century faces major public health problems, triggering calls to reconsider approaches to disease prevention. A key part of the solution is street redesigning, which adds another lane like cyclists and pedestrians. It aims to create healthier and more social-sustainable cities that affect citizens’ behaviour in the time of pandemics [35]. A study by Todd 2020 addressed that pandemic-resilient urban spaces where are people live in a walkable community with low-risk and affordable accessibility opportunities [36]. Also to achieve the principle of social distancing and allow wider spaces among users, many planners find this a good opportunity to rethink the design of the streets by barring cars from some streets and providing more spaces for pedestrians and cyclists which turn the city into green and low carbon [7,37]. Cities like Barcelona have been studying traffic and working to redirect street traffic [38]. Indeed, it has started planning for the expansion of streets in the city [39]. Several cities, such as Vienna, Boston, Oakland, Philadelphia, have closed some roads to increase the area for pedestrians and cyclists as a kind of response to the pandemic. Another example: Bogotá has expanded bicycle lanes and added more temporary lanes. Mexico City has a similar plan by developing bicycle infrastructure to address varied issues like health, safety, economy, etc. [40,41]. In addition, when redesigning the streets and taking into account increased pedestrian spaces and active mobility, many public health goals can be achieved [42].It is worth mentioning when referring to the point of redesigning streets during an epidemic; the new standards of using sidewalks should be considered. Such as social distancing while queuing that requires providing wider sidewalks and paths, and leaving a safe distance about 1.5 m. Adding more space to accommodate the queue at the entrances to public facilities, providing fixed seats for the elderly, and distinguish the individual's point with a sign on the ground [37].

3.3. Public Transport

- Transportation is a key part of every city and urban environment, and thus at the time of pandemics, it is often a gateway to diseases [43,44]. Great restrictions on public transportation were imposed to reduce the spread of pandemics. Because public transportation such as buses, subways, trains, and airplanes have crowded vehicles, the stations increase Coronavirus outbreak and present numerous risks when transmitting infection by touching handles, armrests, and seats [45,46]. These risks are difficult to control without changing health safety strategies within public stations or vehicles in case of reoperation.The health effects of social distancing on transport were to reduce aviation and motorised traffic and to restrict movement [36]. Also, it may appear that there is a need for public transport to differentiate between entering and leaving the transportation stations [37]. These stations will always need frequent purification, transit risks can be minimized by restricting crowding, proper cleaning and sanitising hygiene of employees and passengers, and safety of operators [47], and this really happened in many cities such as Cairo, Wuhan, Rome, Milan, Washington and elsewhere [48].In addition; for improving precautionary measures against COVID-19 at Changi airport in Singapore that is crucial to be operated at all times, even with the changing Covid-19 situation around the world. In a different way; Changi Airport recently introduced contactless screening for returning people. In large waiting areas; using methods such as drawing queues on floors, or using obstacles to maintain social distance, this can be a primary help in protecting the health of airport workers, travellers, and arrivals. Also, cleaning techniques had stepped up such as increasing hand sanitisers across the airport, increasing in cleaning terminals as high-contact areas, disinfecting of touched surfaces (kiosks, machines, counters, floors …etc.), and undergo temperature screening [49-51].

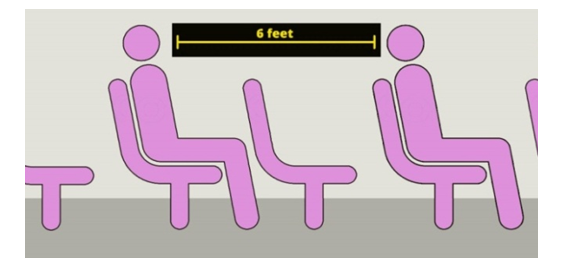

3.4. Public Spaces

- Many public spaces for social interaction are state resources. They include theatres, museums, libraries, public sports facilities, etc. where people can gather and practice activities. One of the most important basic measures to confront this pandemic is social distancing policies to limit places of gathering, as part of those policies; Governments encouraged people to stay at home, abolished or postponed large public events, theatres and museums activities, libraries, sports facilities and closed schools, universities, factories, and markets, as well as restricting the presence in public squares [52,53]. At the time of pandemics; the use of public spaces such as stadiums and conference centres can repurpose for emergency hospitals. The most rapid practical approach was to adapt to existing buildings. [53]. No matter how primitive these temporary hospitals may seem, but they are our best choice. Around the world, the scenario is the same. There are closed hospitals and being reopened, many vacant hotels or stadiums are being retrofitted for health care [54,55]. However, the vast majority of those hospitals are being designed in open areas that describe as arenas.But public spaces have always been a destination for many individuals, and many were centres of religious and cultural celebrations [56]. Therefore the attention of designers can be directed to rediscovering social and recreational uses and redesigning according to human needs and to be designed as pandemic-resilient and flexible spaces [57]. After going through this pandemic, a need may emerge for new guidance for describing public spaces, and designing in terms of distances and densities, or the presence of public health risks [58]; see Figure 3.

| Figure 3. Designing new social distance, [Source: by the authors] |

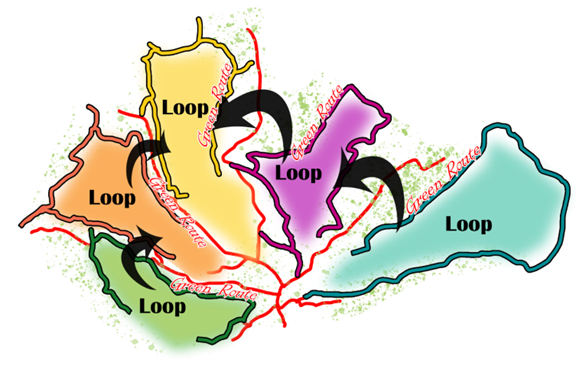

3.5. Parks and Green Areas

- Access to outdoor parks and green areas is a human need that reduces stress and improves physical, psychological, and mental health. Maintaining safe use of green areas is a challenge in terms of control Covid-19 transmission in the outdoor environment [59]. Naturally, the trend in healthy design will be accompanied by increased demand for green areas, where many studies dealt with the importance of visual access to nature, which would enhance the physical and psychological health of individuals [60]. Redistricting of green areas and parks within cities may be considered. Designers may need to create more spaces and practices for individual use in planning green areas such as expanding running tracks, paying attention to small neighborhood parks, As one of the new solutions that allow individuals to enjoy public parks doing what are called social distance circles. This is what has already been done in many parks such as Brooklyn Park, New York's Domino Park, San Francisco's Dolores Park [61].A great suggested idea of green infrastructure, which improves public health benefits, is having a connected system of green areas. This system is more useful than scattered parks, and it means to have a network of different scales and uses parks through which residents can move easier and connect to nature; see Figure 4 [28,61]. As same as in Singapore; a park connected network (PCN) is a green network that can easily connect between densely areas and natural areas, where everyone can explore Singapore through green routes which are based on different loops in the island [62].

| Figure 4. The idea of park connected network [Source: by the authors] |

3.6. Housing Inequality and Building Design

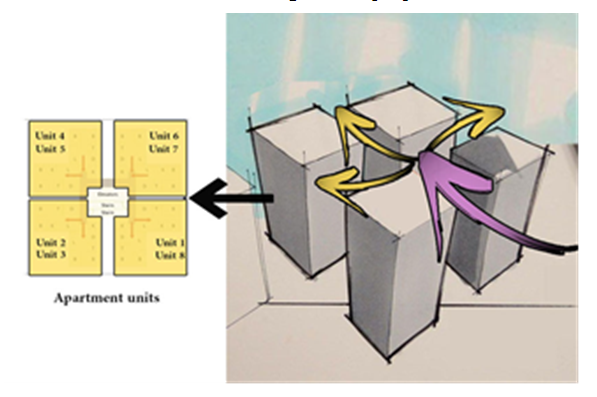

- It is clear to everyone that after this crisis is over, we will not return as before, and one of the most optimistic expectations shows that we are waiting for a new beginning for our lives. It is the beginning of changing values, habits, and our homes. From social behaviour view and after self-isolation; the theory of organizing many people in a multi-story building that looks like boxes isn’t in line with the new uses that are practiced inside the house, and differs from the basic function. Also, from the public health view; living in houses is better rather than in apartments. These findings are as same as the results of many studies examined the increase of illness, mental health, and social wellbeing in flats as compared with houses [64,65]. That’s also compatible with a study by Sennett 2020 in his book "Designing Disorder: Experiments and Disruptions in the City"; who shows that in the near future there will be a new thought in building design and the trend towards broader neighbourhoods that enable people to socialize without having to fill them like sardines, taking into account the healthy foundations of building design [66].From the social behaviour view; contemporary urban residents spend a large portion of their time indoors where they forced to work from home. Thus their health is directly affected by housing space, and this can negatively impact public health if the design is poor [67]. House closures and isolation measures have shattered the traditional concept of house jobs, becoming a place to sleep, play children, and work. Perhaps in the future, we look to change and study the regulations that are more in line with the recommended "social distances", Also interior designs according to new functions that are practiced at home; should pay greater attention to spatial organization. For example; a workplace can be a completely organized private room with appropriate furniture. Hence, this idea should not include residential buildings only, but it should include public buildings of all kinds, schools, waiting rooms, etc. meaning that designers should be design flexible spaces.As a result of household isolation, which leads to paying attention to the quality of homes design in order to improve the general performance of homes, designers should go back to nature in redesigning our homes, or by using biophilic design approach. The presence of natural elements may be a useful way to reduce isolation stress and other psychological effects [68,69], which is compatible with a previous study that recommended to reconsider the untapped places and build rooftops [60]. Also, the importance of maintaining veranda as an outdoor space has many benefits, such as connecting with nature, urban, and green view, and to offer a social connection between neighbours [70].From the public health view; Building can cause diseases, which is known as sick buildings syndrome, and it indicates the effect of building design on human health and the diseases that the building can cause to humans [71]. For example, a lack of interest in the good design of patios and the ventilation of residential buildings leads to the possibility of spreading respiratory diseases. In 2004 the researcher Yuguo Li conducted a study to simulate the transmission of SARS in a residential area in Hong Kong, by analyzing fluid dynamics, where he explained how the disease spread through the ventilation yards of apartment buildings [72]. That indicated the importance of buildings orientation aspect in urban spaces according to pandemic spread behaviour; see Figure 5.

| Figure 5. Simulate how the virus is spread through the residential [Source: drawn by the authors, adapted from [72] |

| Figure 6. (a) High-rise building' risk - (b) Low-rise building' proposal [Source: by the author] |

3.7. Useful Technologies of Smart Cities

- Smart cities can contribute to helping us cope with this epidemic, where some governments have resorted to using smart city technology and may turn to rely on digital data sources that mobile devices and remote sensors to track people infected with COVID-19 [73].One of the experiences of countries that have so far been successful in managing the pandemic confrontation is South Korea experience. The artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have been used as an important part of South Korea's strategy after the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2015. Some of the reasons for success for example; rapidly developing a COVID-19 testing kit in a short time widespread in the republic, using smart quarantine information system by collecting information and obtaining the history of patients’ movement to help them on time [74,75].From 2017 China has already taken a leading global position in the Artificial Intelligence field [74]. China’s experience illustrates that it has also resorted to using technology companies to track the spread of the disease [76]. Thus, we find that smart cities are safer cities from the public health view. In China, the spread of Covid-19 is tracked by using “big data” analysis from tech firms such as Alibaba and Tencent to expect where transmission clusters will emerge next. The authorities find from tracking coronavirus that “smart cities” like Songdo or Shenzhen are healthier cities from a public health view. So we can anticipate great efforts to digitalize our behaviour in urban areas. As the world continues its attempts to confront the spread of the epidemic, which required many changes; some ask about which of these changes will continue even after this crisis and what cities will look like after that. In general, environmental changes increase the risk of epidemics in the future. With the increasing numbers of residents and cities, it is logical to change the way of thinking in designing cities to make them healthier and more stable to face any future challenges. While most of the world's population practice social distancing to reduce the spread of disease, it is important to focus on the functional cities strategy which has good technological and sustainable features; that help in monitoring and collecting infection database.

4. Functional Cities Performance During the COVID-19 Pandemic

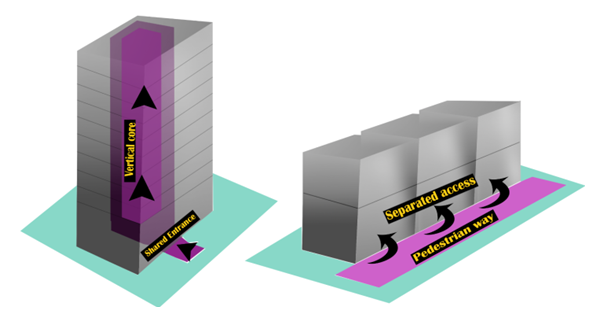

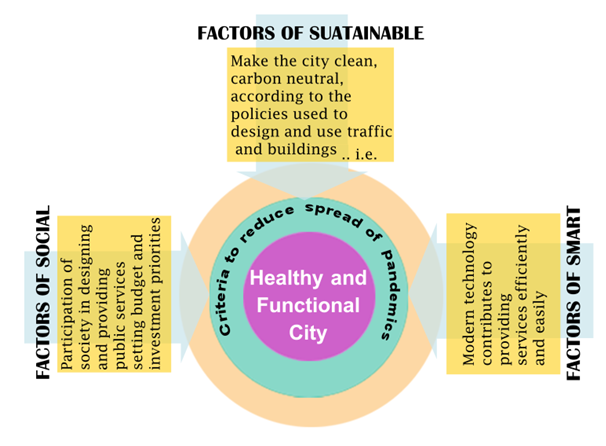

- The pandemic is a major challenge for the cities of the world, whether rich or poor, as the precautionary measures to confront this global epidemic have major impacts on these cities because of their economic structure, public health status, and the extent of the ability to provide different services and livelihoods. Some cities have so far proven successful in managing this crisis; these are known as functional cities.The concept of a functional city is the city that was planned to achieve the best conditions and capabilities for the urban life of its residents and create conditions to achieve an enjoyable life and make life more smooth for the residents within it. It is a city that provides high-quality services to all people in poor or rich neighbourhoods alike [77].One of the most important examples of functional cities is Helsinki, the capital of Finland, with a population of approximately 650,000 people, and it is the largest educational, cultural, research, political and financial centre in Finland, as this city alone provides approximately 40% of the country's GDP. In 2012 the city of Helsinki was chosen to be the capital of international design by the International Council of Industrial Design Associations [78].The city was classified in 2017 to 2021 as the first functional city in the world to provide the best possibilities of urban life for city residents through work, security, and education [79]. "Finland is classified as one of the highest countries in terms of education in schools. There is confidence between the citizens and the government, which makes it easier for the government to manage crises easier and more effectively. It is because the city of Helsinki relies on three main pillars that strongly support the management of the current COVID-19 crisis:The first pillar is that it is a smart city: Modern technology contributes to providing services efficiently and easily. Governments in some countries have resorted to managing the crisis situation and tracking injuries using modern technology and sensors to collect data, providing students with electronic classrooms, providing digital cultural services to citizens to reduce the effects of social isolation, ensuring that older persons over 70 years of age have access to support in shopping, pharmacy, and main needs.The second pillar is that it is a comprehensive city: it shows the participation of society in designing and providing public services and setting budget and investment priorities from the adopted policies.The third pillar is that it is a sustainable city: According to the city plan (2017-2021), the goal of the plan is to make the city by 2035 carbon-neutral, according to the policies used to design and use traffic and buildings, etc. a mixture of "smart and clean" measures. For example, the city has improved public transportation and railways, reducing the use of private cars, adding 300 charging stations for electric cars, so that carbon emissions will be reduced, and encouraged pedestrians and cyclists by increasing their area, the goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 60% By 2030 [79,80]; see Figure 7.

| Figure 7. Helsinki city’ strategy objectives [Source: by the authors] |

5. Conclusions

- The presented research is a review on the impact of the Corona pandemic on cities and urban design, and how they can change after their passage from the perspective of planners and designers of cities and public places. In addition to trying to direct the attention of designers and planners towards trying to find new solutions that achieve a safe and effective environment for individuals.Some cities around the world have begun planning for recovery. Every step towards recovery helps to build a world beyond the COVID-19, and the success of these cities depends on anticipating global trends and transformations - and the result will be a new kind of city capable of withstanding shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic in a more stable way. The epidemic can be seen as an opportunity to rethink the design of cities to better prepare for future crises. Through the study, it is found that the optimal design for cities, especially during the current crisis, is based on three main pillars, which consider the city to be smart, sustainable, and comprehensive, taking into account societal design. These characteristics will make cities more effective in the direction of future crises; see Figure 8.

| Figure 8. Main pillars of the healthy and functional cities [Source: by the authors] |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML