-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2019; 9(2): 23-32

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20190902.01

Public Squares in UAE Sustainable Urbanism: Social Interaction & Vibrant Environment

Issam Ezzeddine 1, Ghanim Kashwani 2

1Architect and Urban Planner, PhD, Heriot Watt University, United Arab Emirates

2New York University Abu Dhabi, Division of Engineering, United Arab Emirates

Correspondence to: Issam Ezzeddine , Architect and Urban Planner, PhD, Heriot Watt University, United Arab Emirates.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

For more than 2000 years, the urban public square has been a distinguishing characteristic of Western cities. For the last 200 years, European and North American cities have been deliberately planned to include public squares with an intention to bring people closer. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the urban public square was a prominent feature in most traditional communities, but, since the late 1960s, this feature has gradually disappeared from urban planning. A consequence of this is that the social fabric of community life has been eroded. Despite support from the UAE leadership and regulatory authorities for developing sustainable communities in line with global compacts, the gap between social life and community urban planning is yet to be filled. This research examines the effectiveness of developing urban public squares in the UAE cities and formulates policies for including such spaces in new districts and communities. Additionally, this research focuses on the concept of new sustainable urbanism in the UAE by integrating public squares as a sociocultural entity within the fabric of new communities for the sake of improving social life and developing vibrant environment.

Keywords: Public squares, Social, Urban design, Liveability, Sustainability

Cite this paper: Issam Ezzeddine , Ghanim Kashwani , Public Squares in UAE Sustainable Urbanism: Social Interaction & Vibrant Environment, Architecture Research, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 23-32. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20190902.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction & Background

- Over the past two centuries, more public open spaces have been provided in European and North American cities in an attempt to build the interaction between people and their communities [1]. Consequently, several countries around the world have followed this pattern, and similarly, cities in the Middle East have endeavoured to do so. However, to accomplish this, a great deal of planning and various factors need to be taken into consideration. A public square is an open public space that is commonly found in the heart of a traditional town, used mainly for community gatherings. A public square is also called a civic centre, city square, urban square, piazza, plaza and town green. Public squares were also used for races, bullfights, executions, or even just to collect rainwater in large underground cisterns. Lennard and Lennard [2] state that “The key to a liveable city is its public realm, the quality of social life that takes place in its streets and squares”. City planners have focused primarily on solving urban problems, such as the proper use of land, the improvement of traffic flow, accessibility [3], and balancing economic requirements [4]. However, these considerations overshadow the civic value of open spaces to communities and cities [5]. The concept of an “urban public space” is a social hub [6] a location where individuals can gather to share thoughts. Arendt [7] argues that a public space is an area where “everything that appears in public can be seen and heard by everybody and has the widest possible publicity”. Others suggest a critical distinction between a public and private urban space [8]. There are several alternative ways of classifying public and private open spaces, chiefly, whether publicly- or privately-owned; government restrictions on usage; and how accessible the space is to the public [9]. Gehl [10] studied European cities with emphasis on the relation between outdoor activities and physical environments, such as the architecture, pathways, and landscaping. Communal open spaces, regardless of size, function and type, are generally considered essential facilitators of healthy social interaction [9-12].A reading of the literature on public realm presents how most of Middle Eastern cities over the past two centuries suffered urban degradation because of social fragility, declining respect for traditions, increasing danger and violence in open spaces, consumer inequalities, and changes in income levels, amongst others [13]. Modernisation and industrialisation resulted in progressively disconnected neighbourhoods with declining popularity of urban squares. A public place where citizens assembled, worked, shopped, or simply mingled lost its relevance. This paper highlights the major formative phases of public urban squares in Middle Eastern urban communities. Its primary emphasis is on those crucial periods and events which led to the establishment of such squares in Arab cities.Modern Arab states have undergone major changes in those social, economic, and cultural structures with Western influence or Western origins, with an intensity that varied from country to country and from city to city [4]. These transformations translated into structural alterations in urban environments that evolved more slowly, with little foreign influence.Moreover, the court or town square, emerged in the late nineteenth century, either as core urban advancement, as per the French, or as extra spaces that were then transformed into urban squares [4]. The maydan is another type of urban open space in Arab cities. It originated as an urban space for equestrian activities in the pre-modern period. Although maydans served as outdoor commercial centres, they were never viewed as public space.Most modern urban amenities were imported as complete de facto entities, conceived and developed elsewhere. They had no neighbourhood history to enrich their significance; they were not the outcome of socio-political struggle typical of pre-modern European cities.

2. Investigation Urbanization

- The key problem of this study is: The process of urbanisation in the UAE since the discovery of oil has led to the loss of open public spaces, with consequent weakening of social coherence and stability, accompanied by inattention to sustainability in the longer term.Cities and communities in the Arab world inevitably face urban transformation, driven by the global context in which cities are being reshaped, and the modernisation of urban planning themes [14-16]. The characteristic architecture of the region is thereby threatened and reflects a loss of fundamental principles, evolved over centuries according to social, cultural, spiritual, environmental and political factors. These problems can be summarised as follows:• The historic diffusion of civic spaces in city plans is elaborated by Zucker [17] and other writers, such as Cleary [18], who focused either on specific squares or on the benefits open spaces have for the quality of citizens' lives.• In the main cities of the UAE, such as Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, and others that have grown over the past six decades, it is noticeable that cities have lost the heritage theme of the old public urban square, which is called Al Fareej or Al baraha area which will be addressed in section 6.• The evident marginalisation of the rich heritage of this region is evident through the significant deterioration in the physical and structural conditions of traditional home environments and the level of services provided to the individuals who live there.• The complete neglect and disregard for the vital role of social and cultural concepts and values of the community.• The lack of focus on the concept of sustainability, and guidelines that can implement what is important, socially and culturally, for future developments in the UAE.

3. Understanding and Applying Approaches to Sustainable Development in Urban Open Space

- Community approaches to tackle the application of sustainability are varied [19]. In the words of Al Waer [20], “...to develop better approaches to sustainable urban development, a deep mandatory competence and collective understanding through dialogue, rather than debate is needed between the future master planning teams”. Over 70 national, regional, and local regeneration and development organisations have committed to investigating the scope of creating more sustainable communities. There are three core aims in developing sustainable communities:• A healthy environment involves minimal ecological impact, minimal waste or pollution, and maximum recycling, protection, and enhancement of the natural environment. Environmental benefits include greenery, physical and social well-being, and space for leisure activities.• A prosperous economy generates wealth and long-term investment and maintains the natural and social capital that all economies depend on. It minimises the use of resources and environmental impact, develops new skills, improves education and training, and stimulates local jobs and services.• Social well-being arises from a sense of security, belonging, familiarity, support, cohesion, and integration of social groups, based on respect for different cultures, traditions, and backgrounds.Based on these approaches, the researcher argues that new urban planning policies adopted by decision-makers and urban planners in the UAE to develop sustainable open spaces and squares in the new community master plans must regulate and include new design guidelines that contemporary architects and urban planners are bound by. The regeneration of public urban squares in cities of the UAE is a major issue as multiple factors have to be taken into consideration during the design stages, including the aesthetics and attractiveness of the location of the square; its accessibility by all population groups (it is imperative to meet the requirements of elderly and disabled people) [21]; local mitigation of urban temperatures in summer; increasing regenerated surfaces; use of eco-friendly materials; reuse of old elements; and using structural techniques and materials that display long durability and resistance to outdoor conditions. Meeting all these factors widens the level of interaction between public urban squares and citizens. However, that crucially requires carefully planned strategies and policy models. Dovers and Handmer [22] suggest that sustainable development can be identified as a pathway for premeditated change and development that balances or instigates the attributes of the system, while still attending to the existing population's needs.

4. Urban Open Space in a Middle Eastern Context

- The Arab region stretches from Morocco on the Atlantic Ocean to Oman and the Arabian Gulf. Language, religion, and history provide a robust and unified identity for the people in these regions [23]. There were two primary planning themes in the Middle East in the Islamic era that substantially impacted on contemporary open spaces: (1) historical Islamic urban planning that relies on retaining ties of social privacy, religion, traditions and culture limiting the role of public open spaces in communities; and (2) contemporary architecture and urbanisation of public open space reflecting Western characteristics in modern Middle Eastern architecture. Cities of the region were shaped by three major principles: Sharī‘ah, social constraints, and natural law [23-24]. This section presents three connected areas in the urban open space.

4.1. Traditional Urban Morphology in the Middle East

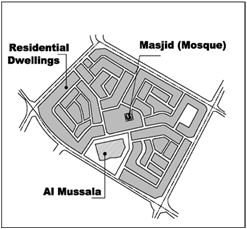

- Historically the Middle Eastern cities evolved around a central nucleus and spread on the four directions forming integrated neighbourhoods connected by narrow streets, alleys, public squares, and gateways. Houses and buildings are interconnected by common walls, steps, public footpaths, and shade canopies to allow children and women to move freely during the daytime hours.The last three decades saw urban open spaces and public squares in Middle Eastern cities neglected by government or municipalities, rarely accessible to the public [25-26]. Germeraad [23] highlights that streets and passageways in traditional Arab cities were never considered simply as vacant spaces between buildings. Instead, they functioned to support community residents. Typology of urban open spaces in traditional Islamic cities varies with similar spaces in the West. The following terms reflect the traditional urban open space in the Middle Eastern region:• Al Musalla is a large, open space mostly isolated from the residential areas and located outside the city or neighbourhood boundary. It is used twice a year by the public as an area for prayer and worship, but mainly for the Islamic festival of Eid [27]. Al Musalla has also been used as a location for political events, social gatherings and preparation of the army for military purposes (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Al Mussala & Al Masjid concept Source: (Researcher’s own) |

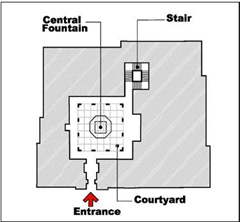

| Figure 2. The house courtyard concept Source: (Researcher’s own) |

| Figure 3. Old Islamic City Source: (Researcher’s own) |

4.2. The Open Space in Middle Eastern Urban Development

- According to Germeraad [23], modern urban design concepts appeared in the mid-19th century during the colonial era, when a considerable development of Middle Eastern cities took place due to the establishment of governments, industrialisation and the onset of the agricultural revolution. As a result, the new developments created new requirements, such as increased demand for roads and vehicle accessibility, causing erosion in the open spaces. Efforts to maintain Arab-Muslim identity in the region increased with the establishment of the Arab League in 1960. Nonetheless, the Middle East considers implementing western urban design a developmental necessity.

4.3. Contemporary Urban Open Space in Middle Eastern Cities

- The understanding of public open spaces has recently been transformed in the region in terms of design concepts and usage. Middle Eastern governments have allowed western concepts to be introduced into cities, including urban landscaping, natural reserves, playgrounds, managed beach areas, outdoor sports areas, waterfronts, streetscapes, and squares and plazas, as part of the modernisation process. Squares and plazas are examples of western ideas that have been transferred to the Middle East. Various aspects of a city’s open spaces have long been used in Islamic cities, such as maydan, saha and rahba. Due to the overlapping linguistic meanings and the fact that the concepts of urban square and plaza are imported from Western regions, there is confusion in the use of these two terms in the Arab.

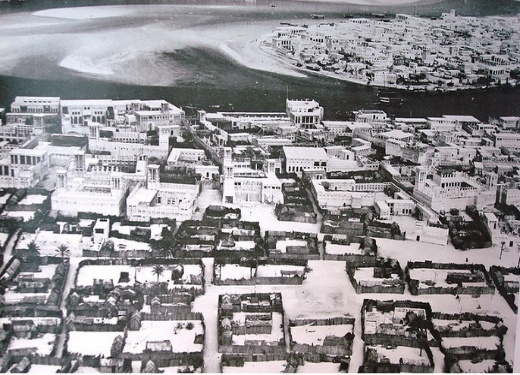

5. The Dubai Case: Historical Profile

- The Emirate of Dubai, situated on the Arabian Gulf, is one of the seven Emirates that form the United Arab Emirates [31]. The city of Dubai comprises of two sections (Deira and Dubai) isolated by a river streaming inland from the Arabian Gulf. The historical backdrop of Dubai retreats a several thousand years [32]. Other than being a port where merchandise was transported between and traded with Gulf nations, Iran, India and East Africa, it is also one of the towns on the road from Iraq to Oman [33]. A timeline of the history of Dubai is presented below:• 1587: The Venetian pearl trader Gaspero Balbi coined the name "Dubai"; he portrayed it as a pearl-plunging town along the Gulf.• 1822: British Lieutenant Cogan provided a description in recording the populace of approximately 1200, that there was a low dividing wall around the town with three watchtowers, and the houses were made of mud. He also provided the first map of the city of Dubai and its elevation from the ocean.• 1833: The Maktoum Family came to power [34].• 1841: A smallpox outbreak in Dubai led to more individuals populated the Deira side of the city and began to construct houses and markets. • 1894: A major fire broke out in the town that faced the Deira which destroyed the settlement. Construction methods changed as powerful and wealthy individuals started constructing their homes from coral stone and gypsum to better protect themselves against fire. Sheik Maktoum Bin Hasher Bin Maktoum became the ruler and is considered to have been instrumental in making Dubai a main trading centre in the Arabian Gulf. He set laws on import and export services and urged the shippers to build up their trade houses in Dubai [34].• 1908 The city expanded rapidly and had reached 10,000 inhabitants. Lorimer [35] recorded the statistics of Dubai in 1908, stating there is no customs, the yearly income is $15,400 mostly from pearls, in Deira side there are 1600 houses and 350 shops. In Shindagha territory, there are 250 houses. In Dubai side, there are 200 houses and around 50 shops. There are around 4000 date palm trees in the town, 1650 camels, 45 horses, 380 colts, 430 dairy cattle and 960 goats. In the stream, there are 155 watercrafts for jumping and exchanging and 20 little vessels "Abras" to take traveler between the two banks of the creek.• 1910-1920: The population of Dubai increased due to merchants and other skilled individuals moving from Iran to Dubai as a result of political circumstances and establishing their own businesses. Immigrants, with their architectural skills and traditions, such as wind-towers, air-pullers and decorative gypsum panels influenced architectural styles in Dubai (see Figure 4).

| Figure 4. Dubai in 1920 Source: [37] |

| Figure 5. Dubai in 2016 Source: [38] |

6. The Evaluation of UAE Public Spaces

- Architecture is the mirror of history. Everywhere throughout the world, the importance of past civic establishments might be seen through the architecture of urban communities, fortresses and sanctuaries. The establishment of urban areas relies on different components, for example, topographical, political and social impacts. On the Arabian Gulf, most urban areas have been built along the coast [39]. Creeks gave safe ports for dhows. Moreover, the ocean provides a helpful method of transportation, in addition to being a means of giving nourishment and pearl harvesting. The other important element for cities that developed along the Gulf coasts was the availability of fresh water from freshwater creeks. Dubai eventually developed into a hub of commercial activity where people of different cultures and traditions came from far and wide, settled and inter-mixed, resulting in the unique community of today [40].

6.1. UAE Old Open Spaces

- United Arab Emirates’ main cities, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Sharjah, have grown considerably in the past six decades. With age, these cities have lost the heritage theme of the ‘Old Social Public Space’ or what is known in Arabic as al saha, al baraha or fereej area that is surrounded by the houses and reached by narrow pathways called Sikka. The old Public Space was the area of entertainment, social collaboration, and market space for the residents within a pedestrian-friendly environment. Al Shindagah and Al Bastakiyah are two current areas in Dubai containing few old squares to date, that were restored by the Dubai Municipality at the end of the 1970s. There is, therefore, a need to understand the nature of this emerging type of urban space within its community, in order to achieve sustainable environmental spaces. Likewise, urban planning has transformed the old community open space to either a commercial intersection of main roads dominated by vehicle movement or used as parking lots to serve the trading domain [41]. As a result, the public open spaces have been converted from social spaces characterised by vibrant, lively interaction into areas supporting the transportation and movement of service yards.Al Nasser square, known as Baniyas Square, shown in Figure 6, is located in the central section of Dubai Deira district and considered one example of old public open spaces located at the Old Souk area of Dubai, on the creek side. The Baniyas square was the social and trading station of Dubai before the modernisation of the city began to unfold in 1966 after the first oil well was established. It used to be an important destination for traders and pearl merchants, focused on the economic and social activity of the area, and a place for people to gather and to celebrate their festivals. Nowadays, the square is a network of roads and scattered parking areas integrated with little soft and hard landscaping elements. The square has its social and cultural identity and has become a primary metro station zone for traders and shoppers.

| Figure 6. Al Nasr (Baniyas) Square in Deira Dubai- 1956 [42] |

6.2. The Forgotten Urban Public Squares in the UAE

- Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Manama and Doha have common characteristics of urban squares (al saha) linking the different strata of the community social fabric together. Al saha, Al maydan or Al baraha, all have one meaning–public urban square. They used to be the centre of social life and family gatherings, but they were open spaces used more privately between families and not accessible to the public. At the beginning of the 20th century and up until 1960, urban squares were important places for social gatherings and customs.Hasty urban, demographic, and economic growth alongside land privatisation process has progressively changed the nature and theme of public squares within the UAE community and widely the city. However, the few remaining squares and plazas in the UAE no longer hold true to their nature, they are no longer places for social gathering or public entertainment, but have now been converted to roads and street intersections or have been deconstructed into parking lots. Until the mid-1980s, the disappearance of squares all over cities of the UAE took place without the consideration of historical origins, and the social and cultural value of public squares in the UAE.

6.3. Public Open Spaces in Dubai 2000-2015

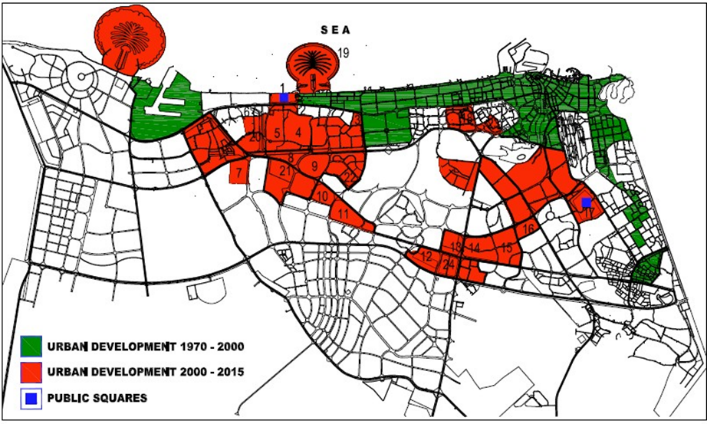

- Currently, urban public squares for people to socialise and interact in UAE cities are almost neglected in urban and city planning design strategies. The Emirate of Dubai witnessed two periods of urban development (Figure 7). The first was between the year 1970 and 2000, which represents three decades of conservative urban development. The second occurred between the years 2001 and 2015, fifteen years that included what was called the “Boom” period. During both periods, neither open spaces nor community public squares were a concern in the new development of the city.

| Figure 7. Dubai Map–Two different periods of urban development Source: (Researcher’s own) |

6.4. Old Public Squares in the UAE–Al Fereej, Al Saha & Al Baraha

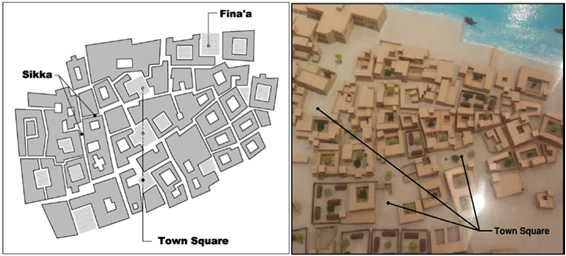

- One of the most effective social bond and cultural traditions in family life in the UAE is the constant interaction with others. The old, haphazardly-planned community was based on setting houses close to each other with narrow passageways in between, all linked to an open space for people to gather and entertain. This section focuses on typologies of public open spaces and squares that characterise the urban morphology of the UAE old city.

6.5. Old Public Squares in the UAE–Al Fereej, Al Saha & Al Baraha

- One of the most effective social bond and cultural traditions in family life in the UAE is the constant interaction with others. The old, haphazardly-planned community was based on setting houses close to each other with narrow passageways in between, all linked to an open space for people to gather and entertain. This section focuses on typologies of public open spaces and squares that characterise the urban morphology of the UAE old city.

6.5.1. Al Fereej

- Al fereej is the term given to traditional housing organised around a public open space Al saha means a place for people to gather and socialise (Figure 7). The traditional term Al fereej formed the building blocks of communities and cities where families were clustered together as urban settlements [51]. Nowadays, new housing layouts and the urban planning systems in the UAE have completely forgotten this terminology.

6.5.2. Al Saha

- The researcher as an urban planner prefers to use the popular local term Al saha to refer to open spaces that are on the fringe of a town. Al saha is a semi-public space, located in neighbourhoods inhabited by a clan or tribe (Figure 7). It has parallels in western cities, in what Kostof [52] has named “the clan piazza”. These are described by Kostof as family squares surrounded by the clan’s property. Most old UAE cities were built following the same clan or tribal structure. Moreover, these cities’ neighbourhoods were named after particular tribes, clans or guilds. Yet, actual public spaces, although unplanned, were either external to the city or in open spaces between these family neighbourhoods. Kostof provides the example of Genoa as a city that remained without a large public space until 1460. Those spaces were and are still referred to as saha (singular) or sahat (plural). Similar to the city of Genoa, the growth of the public sector and the formation of a bureaucratic system in UAE cities, which started in the 1920s, occurred in open spaces (sahat), in palm forests (nakhal) and on waterfronts (seef). Hakim [27] reports that a saha in Arabic terminology refers to a public square or an open space that is typically shaped as a Y-intersection of three distinct lanes. These sahat are inside the urban fabric of the city. Nevertheless, actual public spaces, although unplanned, were either external to the city or in open spaces between family neighbourhoods. Other than his description of a saha and its purpose, Hakim describes other spaces as a part of the urban morphology of the Arab-Islamic city, two of which are located outside the city's walls. One square used occasionally is known as the mussalla, an area where petitions are made to Allah, and the other, the Magbara, regularly used as an open burial ground. In UAE, saha is an open space that is larger than the Baraha, yet it could be a space that is either located within the city's urban fabric or on its fringes. The medium-sised scale of UAE towns and cities made it essential to include the sahat, particularly in the densest cities such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The medium scale allowed city-dwellers to reach those public spaces with relative ease (as they were less than 2km from the centre of the town). The open spaces around the old UAE cities had similar characteristics to those of Old Tunis, where those spaces accommodated public cemeteries. In the UAE, these were located on the creek edge, such as the Al Shindagah and Al Bastakiya areas. The saha, in other Islamic cities and towns, is used for many different purposes, such as the open spaces used for playing equestrian events in historical Persian cities. The Al Sahat, when referred to in the UAE, are similar to open fields or forests in the western context which attract users across the spectrum of age groups and are used for many different purposes. These comparisons do not explain the fundamental nature of this sort of space nor why there is little explanation of it in historical records. Akbar [53] states that in the literature on the traditional form of the Arab-Islamic city, the focus is usually on the product rather than the societal process. Conversely, the researcher found that the bulk of the historical record on the socio-political environment in UAE cities focuses on events and overlooks the square. Thus, on the one hand, attention is given to the physical aspects of the place while its societal function is ignored; while on the other hand, we see a more in-depth focus on placeless events. Without any physical reminders that could exemplify these sahat, and due to the lack of historical records, the saha, as a concept and part of the urban morphology of the old town, has been lost. Only Al Shinadagah and Al Bastakiya in Dubai continue to exist, due to their physical remains remaining unchanged. Another factor that could have assisted in the success rather than the current neglect of this type of open space is that the morphology of the Arab-Islamic city focuses on large-scale cities, for example, Baghdad or Cairo, or on small-scale settlements. In both cases, the saha as a type of open space has less importance due to the scale of the settlement. In the large-scale cities, the focus is usually on the spaces that are accessed by city-dwellers on a daily basis. This also applies to villages where we find only one or two open public spaces in the heart of the village that are accessible to all people. These are usually able to accommodate most collective activities which obviates the need for marginal saha. However, in medium-sised cities, such as Manama and Muharraq in Bahrain, the situation is different, and the hierarchy of public open spaces is not the same. Referring to the example of Tunis, we find from Hakim's diagram [27] that there are some sahat on the fringes of the city but still within the city walls. The origins of this could have been a marginal saha that turned over time into a square, with shops serving both local residents and others from outside the city. However, the saha has a transitory nature in UAE cities. Due to its open and almost unmarked nature, the saha is the often the first victim of the city's urban expansion. Similar to UAE cities, the origin of Muharraq city in Bahrain is recorded as being in the middle of the island, which means that it was originally surrounded by sahat that separated it from the sea. The expansion of the town forced its residents to find other locations for sahat, to accommodate both their daily industrial, social and cultural and their occasional needs [54]. Nonetheless, the author argues that sahat face severe challenges for several reasons, particularly those on the waterfront due to property privatisation and the transformation of the coastal strip to resorts and mixed-use complexes. Furthermore, sahat in the towns suffered a sombre fate. With any country in the west, those open spaces are generally private property, so they were typically developed to satisfy the inhabitants and users, but regrettably, in the Middle East region, these open spaces which tended to serve the public were destroyed by the authorities’ decisions to convert them or construct road networks without seeking the opinion of the public.

6.5.3. Al Baraha

- Al baraha is the specific term used to describe the open public space that is between homes and the coastal area [54]. Furthermore, Al baraha within the UAE context is another term used to describe an old public open space. These terminologies or spaces need to be brought to the urban planning decision makers as they are key areas that seem to be neglected. In the UAE, few historical areas remain unchanged, and the decision was taken to restore the remaining parts of the old districts. For example, Al Shindagah and Al Bastakiya, two districts in Dubai located with their scattered open spaces on the creek edge, are now considered the only historical areas to reflect the old community (Figure 7).

7. Conclusions

- This paper examined the evolution of public squares in the Middle East, and specifically focused on understanding and applying urban design approaches to UAE sustainable development in urban open space. A key issue was how urban space and sustainability are related, and the importance of sustainable urban development in the social life of a community was explored. This was contextualized to communities in the Middle East, and the discussion traversed the history of open urban spaces in the Middle East from traditional to contemporary urban morphology. The forgotten urban public squares in the UAE such as Al Fereej, Al Saha and Al Baraha were described in order to create a profile of traditional Middle Eastern cities. In doing this, the public square was highlighted as an element of traditional architecture, leading to an analysis of the need for urban conservation and the creation of eco-villages and eco-cities, and the role of urban architecture in the creation of eco-cities in the UAE. This paper concluded with a detailed description of the urban paradigm and character of the UAE, with a focus on the traditional urban theme of Dubai. Moreover, this paper was intended to highlight the essential of a careful balancing act that involves collaborations between urban planners, designers, and local governments, to articulate policies for urban public squares that explicitly advance social interaction, environmental equity, and vibrant urban communities in UAE.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML