-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2018; 8(4): 111-122

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20180804.01

Building Shape that Promotes Sustainable Architecture. Evaluation of the Indicative Factors and Its Relation with the Construction Costs

Alfredo Esteves1, 2, Matias J. Esteves1, 3, María V. Mercado2, Gustavo Barea2, Daniel Gelardi1

1Facultad de Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Diseño, Universidad de Mendoza, Mendoza, Argentina

2INAHE – CCT CONICET, Mendoza, Argentina

3INCIHUSA – CCT Mendoza, Mendoza, Argentina

Correspondence to: Alfredo Esteves, Facultad de Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Diseño, Universidad de Mendoza, Mendoza, Argentina.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The energy that the building sector consume including both, the production and operation of buildings are directly proportional to the shape and the thermo-physical properties of the building envelope. The shapes that the architect decides on influences the costs of the construction as well as the energy demands for the life-cycle of the building. The present paper analyse four factors indicated by the bibliography to measure efficiency of the shape of the building. These relate different building variables: Envelope Area of Building (Ae), Conditioned Volume (Vc), Floor Area of Building (Ac), Perimeter of Building (Pb). The four factors studied are: Compactness Factor (Ae/Vc); Characteristic Length (Vc/Ae); Compactness Index (Pb/Pc) and Shape Factor (Ae/Ac). This paper also explores the relationship between the SF (shape factor) and the cost of the construction of the building in relation to floor area, where a high degree of correlation is found, high R2 (<0.89). Therefore, it can be concluded that SF optimizes decisions concerning the shape of building in order to reach lower surface areas (compatible with an aesthetic, harmonic and functional design) that yield the lowest economic and energetic costs of construction.

Keywords: Building shape, Sustainable architecture, Construction costs, Design tools

Cite this paper: Alfredo Esteves, Matias J. Esteves, María V. Mercado, Gustavo Barea, Daniel Gelardi, Building Shape that Promotes Sustainable Architecture. Evaluation of the Indicative Factors and Its Relation with the Construction Costs, Architecture Research, Vol. 8 No. 4, 2018, pp. 111-122. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20180804.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The shape given to a building envelope dictates its expression on various levels. This architectural expression that is deployed is also the limits of their technological connections, a demonstration of the relationship between space and function as well as the dialectic between material resistance, limits and space [1].New In the planning process, the architect has to deal with the concept of a building without the guarantee of a special predetermined structure, precisely because it is the product of a speculative, critical and discursive process [2]. The shape of an architectural expression acts as a synthesis of the content, of the knowledge and concept that all interact in the architectural project. In addition, the architect must also necessarily consider the economy of the construction, which is usually a variable that presents great difficulties because it is omnipresent and restrictive [3].Furthermore, in the process of an architectural project, it is necessary to take into account that buildings are surrounding by and located within an environment, and the ‘technical-numerical approach’ is necessary for achieving an architecture that is harmonious with the environment and, in which, the resident becomes the first factor in consideration [4].It is important to keep in mind that, in order to survive, the human habitat must generally have the presence of three skins: our own skin (first skin), appropriate clothing (second skin); and, the envelope of the building (third skin). In some climates the first skin is sufficient, in others, the three are required [5].In temperate, cold or very cold climates, the envelopes of a building not only constitute image and/or structural support but also create interior environments and act on the surrounding environments.The design of buildings must take into account the local climate along with the economic and ecological aspects of sustainable architectural principles [6]. This results in lowering costs which will decrease energy consumption for both the costs of construction and the operation of the building [7]. In addition, these climatically responsive building can enhance its users ‘sense of well-being’ while it teaches them about the experience of using of inherent renewable resources [5].Taking into account that the life of a building is long, it should be clear that it is necessary to think about the distant future and be willing to incorporate ecological technologies whose benefits will be perceived throughout the life of the building and will provide shelter and protection for several generations of users [8].In the design of habitable environments, the basic function of architecture will always require a knowledge of the control parameters that affect the interior comfort and meditate the external environment [4].Tiberiu et al. [9] indicate that the shape of a building has a direct impact on the required energy to heat or cool an occupied space as well as on the initial cost (the construction cost). The environmental impacts of the building sector it is well known. In 2010, worldwide, 35% of GHG emissions (Greenhouse Gas Emissions) were released by the energy sector, which includes indirect CO2 emissions (% of total anthropogenic GHG emissions) from electricity and heat production [10]. According to IPCC, ‘Adaptation can reduce the risks of climate change impacts, but there are limits to its effectiveness, especially with greater magnitudes and rates of climate change’. Approaches for managing the risks of climate change through adaptation include: building insulation; mechanical and passive conditioning of a building; technology development, transference and the diffusion of technology and changes in building standards and practices, among others.The morphology of the building envelope in temperate, cold or very cold climates is an important factor that can influence three very important aspects: 1° on the construction cost of building, 2° in the amount of required energy for conditioning the interior space of the building and 3° if fossil fuels are used to supply auxiliary energy to temper the interior of the building, will all have direct environmental impacts and will influence GHG emissions. It is important to control heat transfer from the interior to the exterior, by reducing the internal-external thermal exchange, that is to say, by reducing envelope surfaces. It is possible to achieve a reduction by implementing an energetically efficient project with walls and surface roofs as small as possible. There are different factors, proposed in the bibliography, that help control the relationship between the projected building shape and an energetically efficient building shape. These factors demonstrate important relationships concerning the following variables: envelope surfaces (walls and ceilings) – Ae; conditioned area of the floor plan (Ac), volume of the interior space (Vc), the perimeter of the ground floor (Pb), etc.Watson and Labs [11] proposes two additional parameters that help describe the efficiency of the shape of the building: SVR – Surface to Volume Ratio (Ae/Vc) and SFAR – Surface to Floor Area Ratio (Ae/Ac). In 1999, Mascaró [12] presented the Compactness Index, (IC), which calculates the perimeter of a circle whose surface is equal to the floor surface of the building with respect to the perimeter of the building (Pc/Pb).Bergmann et al., [13] present Ae/Vc as a Form Factor that indicates the limits of floor plans and volumes and Goulding et al. [14] present this variability in relation to tower apartments.Esteves et al. [15] present an evaluation of the indices indicated by Watson and Labs [11] that shows the advantages of using the shape factor (Ae/Ac) – called FAEP – (Factor de Area Envolvente/Piso - its acronym in Spanish). Filippín and Larsen [16] use the FAEP factor (Ae/Ac) in order to show the compactness grade of a building. Roaf et al. [5] writes about how shape can influence energy efficiency using the Compactness Factor (Ae/Vc) and how it applies to different forms of the floor plans.Rodriguez Urbinas [17] indicate that European Committee for Standardization (2007) proposed two parameters called Compactness Ratio (Ae/Vc) and Shape Factor (Ae/Ac) that highlight the importance of an efficient shape for a building. Stevanovic [18] published a review of papers oriented towards the optimization of passive solar design strategies in buildings. The author shows how decisions regarding the shape of a building have the largest influence on building energy use through energy simulations (with Energy Plus or DOE2). This study demonstrates how energy consumption is heavily influenced not only by the exchange envelope surface but also the thermophysical properties of the materials of the enclosure and the amount of absorbed solar energy as well as solar protection. AlAnzi et al. [19] study the impact of high rise building shapes on energy efficiency using simulations of different shapes: L, U, and H. These shapes for office buildings in Kuwait are studied by correlating annual energy use with relative compactness (RC). These figures are calculated as a normalized ratio of the volume (Vc) to the exterior wall area (Ae).Ourghi et al. [20] study rectangular and L shaped floor plans of a building and AlAnzi et al. [19] extend this study to several other building shapes, such as U, T, H types and others.Geletka and Sedlákova [21] analyse building shape and its impact on shape factor (calculated as the relation of the envelope surface to the enclosed volume - Ae/Vc). The impact is calculated by the energy consumption that is obtained through thermal simulations (using Energy+) for several simple and complex shapes. Grobman et al. [22] inspired by the forms of enclosures existing in nature, they seek to improve the thermal performance of the building envelope.Ling et al. [23] study the shapes of high-rise buildings in order to minimize direct sunlight falling through the façades, which is critical knowledge for summer. In this case, the width-to-length ratio (W/L) of the building for square, circular or elliptical bases are evaluated. These authors found that a W/L ratio of 1:1 produces the lowest insolation of buildings of all cases as well as highlighting the importance of the orientation of the façade.Other investigations seek shape optimization using computational methods of simulation (usually in Energy +) to generate a design and to calculate its response in the given climate. The point is that the simulation should be processed by Energy +. This procedure is not obvious, and this practice is not widespread among the architects of buildings, mainly in developing countries. It is important to increase architects ' capacities to design adequate low-cost (economic and energetic) buildings that also generate safe interior climates during extreme weather events [24]. This present investigation would like to stress that there is a problem of terminology because the same factors have different names. This paper proposes the most appropriate term in each factor regarding their behaviour and responses to different compactness of building envelopes. These lack of compactness refer to either the perimeter of the building or to volume. This paper also explores the relationship between the shape of building and its economical and energetic costs of the construction.

2. Factors, Proposed Terminology, Calculation Equations and Limits

- The loss of energy (heat) from the interior to the exterior in winter occurs through the surface, which is perpendicular to the flow. In order to control this loss, it is necessary to reduce the form, which also affects the cost of construction.Only the above-ground surface area of the building envelope is significant for determining the surface of loss since the most severe climatic stresses occur through exposure to ambient temperatures and to winter winds. In order to conserve either heat or cooling, the building must be designed with a shape that is as compact as possible to reduce heat transfer to the exterior.This includes when there are restrictions concerning the choice of materials and funds for financing the construction of houses. It is necessary to take these measures into account and build with minimum resources, which is especially of interest in developing countries.In addition, transporting costs for materials that are not regional or even domestic is very expensive and these costs should be as small as possible. In the preliminary stages of the architectural project, it is very useful to have figures handy in order to control the quantity of the materials as well as the cost of labor that will be used in construction. Regarding the available literature, there are four factors that define (high or low) the compactness of the building envelope. The following presents each figure, its calculation equation and appropriate value limits as well as a name based on the bibliography.(1) Compactness Factor (CF): expresses the relationship between building envelope surface area (Ae) and the conditioned space volume (Vc). It is calculated according to the Ec. 1. It was also called Form Factor in EnEU 2009 [25]; Shape Factor in Ecohouse 2 [5] and Surface to Volume Ratio - SVR [11].Where:

CF = Compactness Factor [m-1]Ae = Envelope area of building [m2]Vc = Conditioned space volume [m3]For any given building volume, the lower the CF, the greater the compactness of the buildings. Its limits are between 0,6 – 1,2 m-1 for a detached house and from 0,3 to 0,4 m-1 for 10-story apartment houses [13]. Lylikangas [25] indicate 0,8 – 1,0 m-1 for single family house and reduce it to 0,5 m-1 in German EnEV2009.(2) Characteristic Length (CL): it is the inverse of CF. This component describes the relationship between the conditioned volume of space (Vc) with respect to the envelope area of building (Ae). It is calculated according to the Ec. 2. It has been called compactness ratio [17] or Building Shape Factor [9] too.Where:

CF = Compactness Factor [m-1]Ae = Envelope area of building [m2]Vc = Conditioned space volume [m3]For any given building volume, the lower the CF, the greater the compactness of the buildings. Its limits are between 0,6 – 1,2 m-1 for a detached house and from 0,3 to 0,4 m-1 for 10-story apartment houses [13]. Lylikangas [25] indicate 0,8 – 1,0 m-1 for single family house and reduce it to 0,5 m-1 in German EnEV2009.(2) Characteristic Length (CL): it is the inverse of CF. This component describes the relationship between the conditioned volume of space (Vc) with respect to the envelope area of building (Ae). It is calculated according to the Ec. 2. It has been called compactness ratio [17] or Building Shape Factor [9] too.Where:  CL = Characteristic Length [m]Vc = Conditioned space volume [m3]Ae = Envelope area of building [m2]The Passive House Standard (2007) indicates that, typically, for dwellings with the same total treated volume, this parameter has low values for detached houses, low-medium for semi-detached houses and, medium-high in terraced houses. Minimum compactness values are around 0.8 m and maximum around 2.2 m.Both CF and CL are helpful when considering building shape in relation to energy consumption for heating and cooling the indoor air in relation to volume. However, these are not good indicators when it comes to considering the amount of surface area of the building that involves heat transfer from the building. This is especially relevant when it comes to making the surface of the envelope more efficient with inclined roofs, as will be seen later.The unit measurement for CF – Compactness Factor is m-1, which, is not very appropriate for understanding its effect on the shape, but its inverse CL-Characteristic Length has the unit (m) and is more appropriate for understanding the effect of the shape of the building.(3) Compactness Index: is calculated as the perimeter of a circle whose surface is equal to the floor surface of the building with respect to the perimeter of the building. It is calculated according to Ec. 3. It has been called Compactness Index by Mascaró [12] and Amarilla [3] and Andersen et al. [26] apply it to study the compactness of the building's floor. Where:

CL = Characteristic Length [m]Vc = Conditioned space volume [m3]Ae = Envelope area of building [m2]The Passive House Standard (2007) indicates that, typically, for dwellings with the same total treated volume, this parameter has low values for detached houses, low-medium for semi-detached houses and, medium-high in terraced houses. Minimum compactness values are around 0.8 m and maximum around 2.2 m.Both CF and CL are helpful when considering building shape in relation to energy consumption for heating and cooling the indoor air in relation to volume. However, these are not good indicators when it comes to considering the amount of surface area of the building that involves heat transfer from the building. This is especially relevant when it comes to making the surface of the envelope more efficient with inclined roofs, as will be seen later.The unit measurement for CF – Compactness Factor is m-1, which, is not very appropriate for understanding its effect on the shape, but its inverse CL-Characteristic Length has the unit (m) and is more appropriate for understanding the effect of the shape of the building.(3) Compactness Index: is calculated as the perimeter of a circle whose surface is equal to the floor surface of the building with respect to the perimeter of the building. It is calculated according to Ec. 3. It has been called Compactness Index by Mascaró [12] and Amarilla [3] and Andersen et al. [26] apply it to study the compactness of the building's floor. Where: CI = Compactness Index [%]Pc = perimeter of a circle whose area is equal to the floor area of the building [m]Pb = perimeter of the exterior walls of the building [m]Its value is between 1 and 100. The value of 100 corresponds to maximum compactness. CI is useful for considering an efficient floor layout, but it does not indicate anything about building volume. In other words, a taller building will have the same CI when compared with another despite the fact that it has more exposed surface. (4) Shape Factor (SF): expresses the relationship between the surface area of the building envelope (Ae) and the conditioned floor area (Ac). It is calculated according to Eq. 4. It has also been called SFAR – Surface to Floor Area Ratio [11] and FAEP [15, 16]. Where:

CI = Compactness Index [%]Pc = perimeter of a circle whose area is equal to the floor area of the building [m]Pb = perimeter of the exterior walls of the building [m]Its value is between 1 and 100. The value of 100 corresponds to maximum compactness. CI is useful for considering an efficient floor layout, but it does not indicate anything about building volume. In other words, a taller building will have the same CI when compared with another despite the fact that it has more exposed surface. (4) Shape Factor (SF): expresses the relationship between the surface area of the building envelope (Ae) and the conditioned floor area (Ac). It is calculated according to Eq. 4. It has also been called SFAR – Surface to Floor Area Ratio [11] and FAEP [15, 16]. Where:  SF = Shape Factor [dimensionless]Ae = Surface area of building envelope [m2]Ac = Conditioned floor area [m2]The lower the SF value for a given floor area, the better the performance of the building. Although the minimum value depends on the floor area of the building, the indicative SF value in a compact form is between 1 and 2 [7]. The semi-sphere, for example, has SF =2 for all cases and has the lowest envelope surface, (Ae) for any given floor area until approximately 150m2. For buildings with larger floor areas, the most efficient value of SF is less than 2 for the prismatic shape. Values of less than 1 are not recommended due to difficulties concerning natural interior illumination as well as ventilation.Then the efficiency of these factors are then studied in different situations of distinct compactness (in floor area and in volume).

SF = Shape Factor [dimensionless]Ae = Surface area of building envelope [m2]Ac = Conditioned floor area [m2]The lower the SF value for a given floor area, the better the performance of the building. Although the minimum value depends on the floor area of the building, the indicative SF value in a compact form is between 1 and 2 [7]. The semi-sphere, for example, has SF =2 for all cases and has the lowest envelope surface, (Ae) for any given floor area until approximately 150m2. For buildings with larger floor areas, the most efficient value of SF is less than 2 for the prismatic shape. Values of less than 1 are not recommended due to difficulties concerning natural interior illumination as well as ventilation.Then the efficiency of these factors are then studied in different situations of distinct compactness (in floor area and in volume). 2.1. Study of the Response of Each Factor

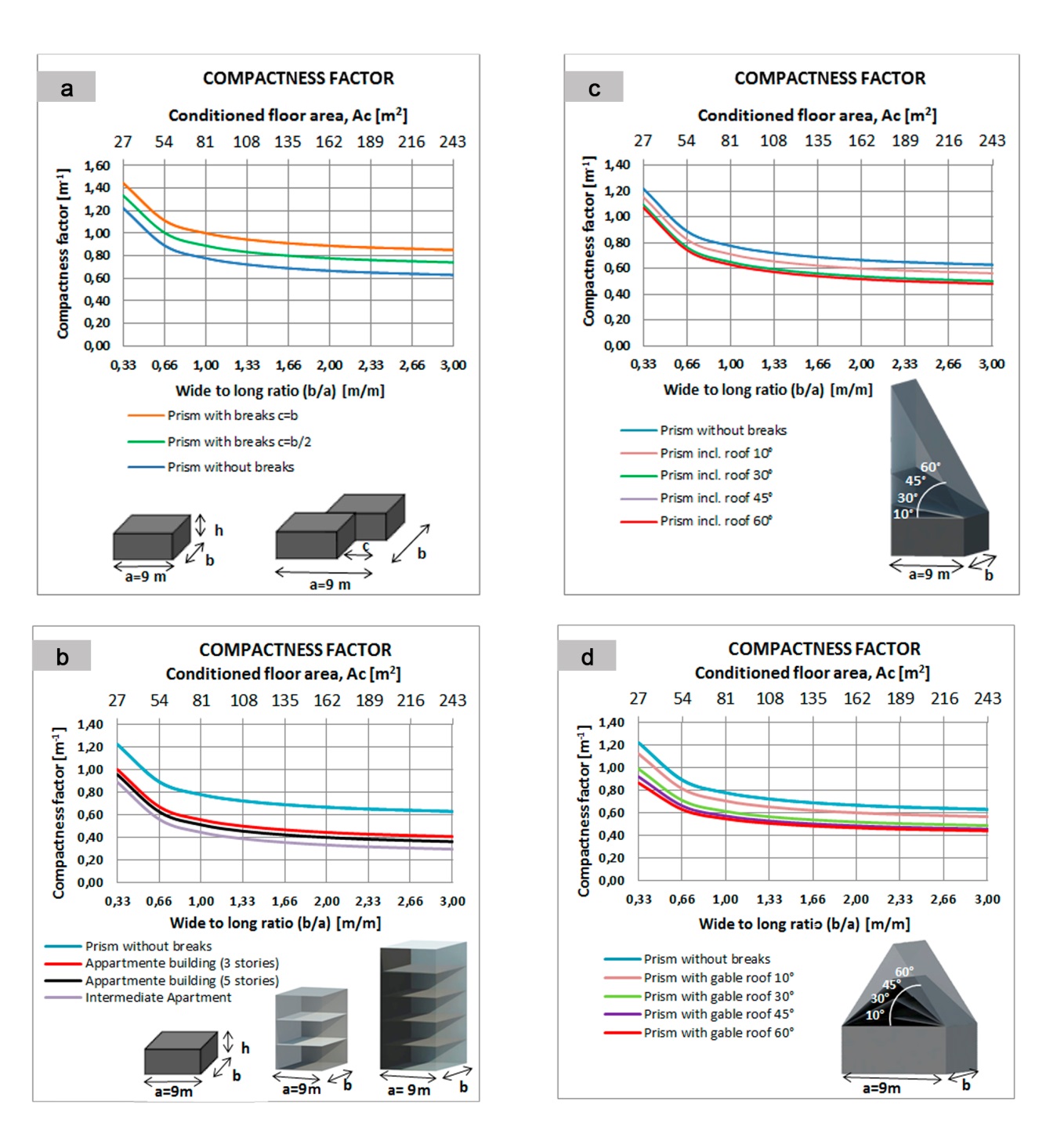

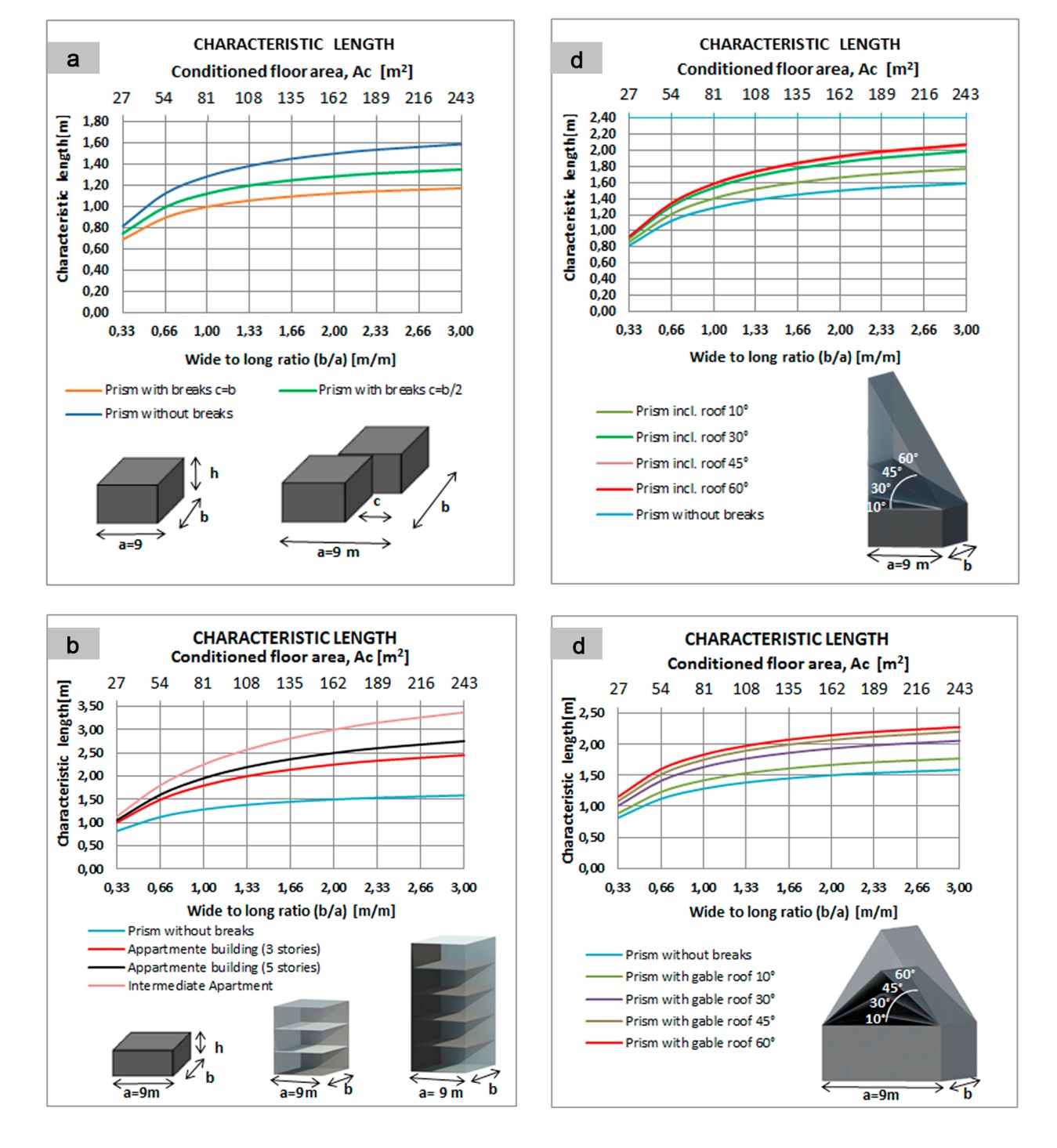

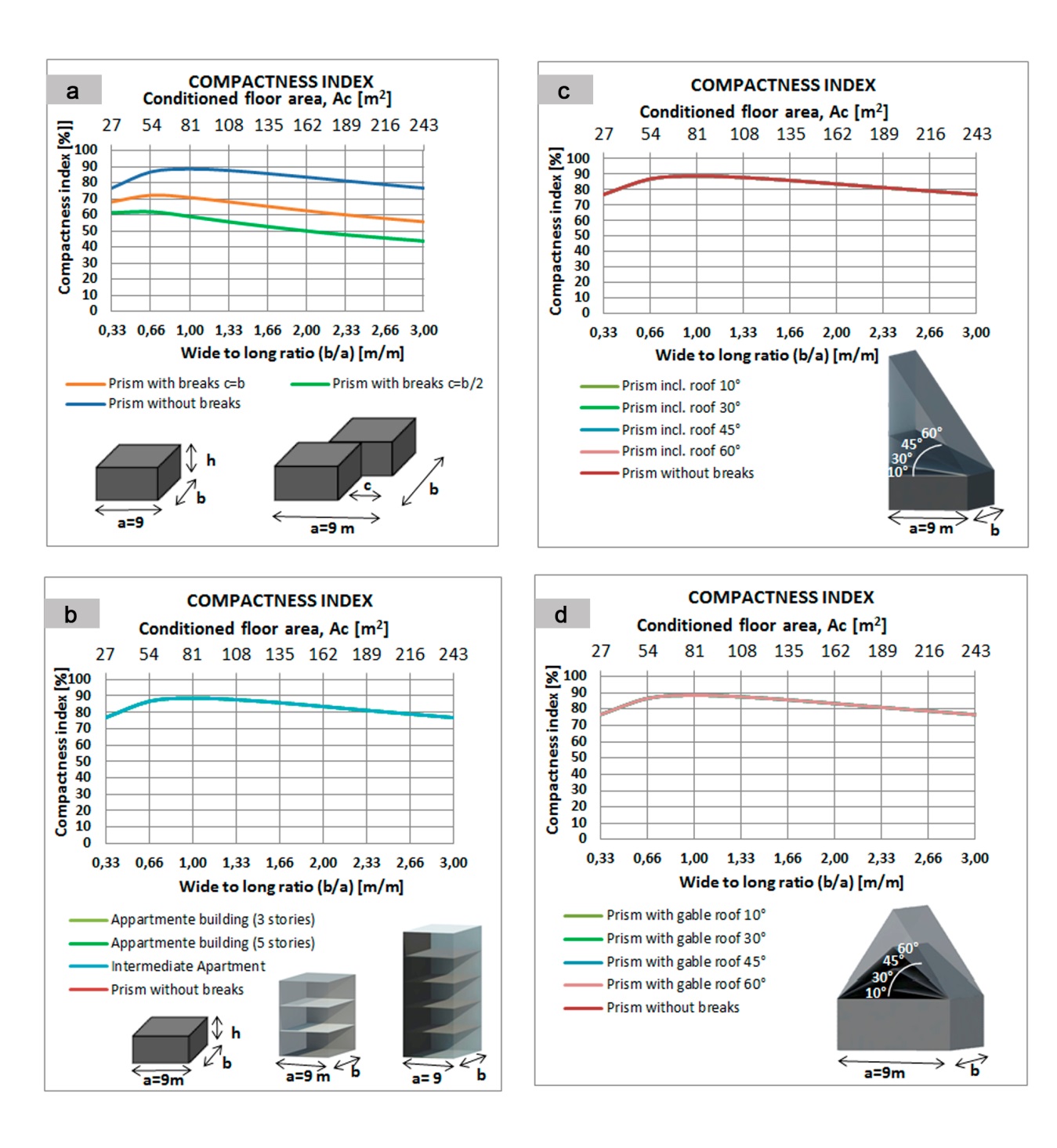

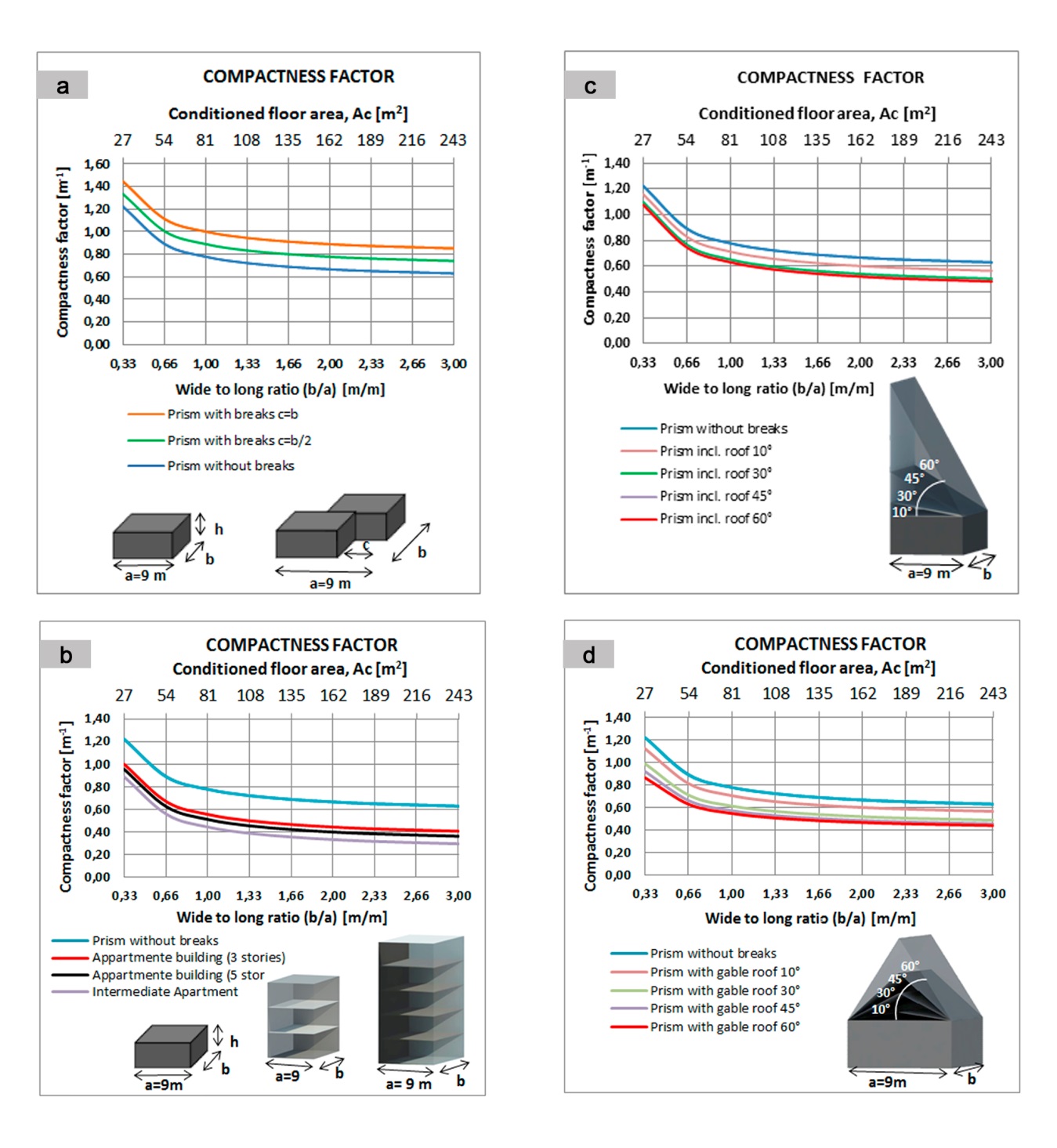

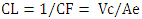

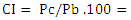

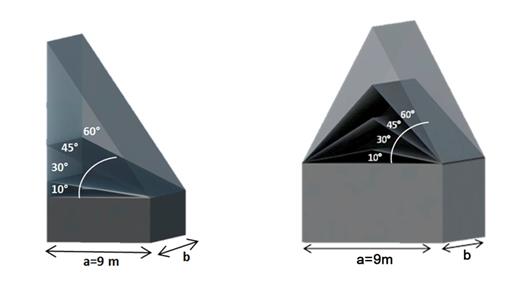

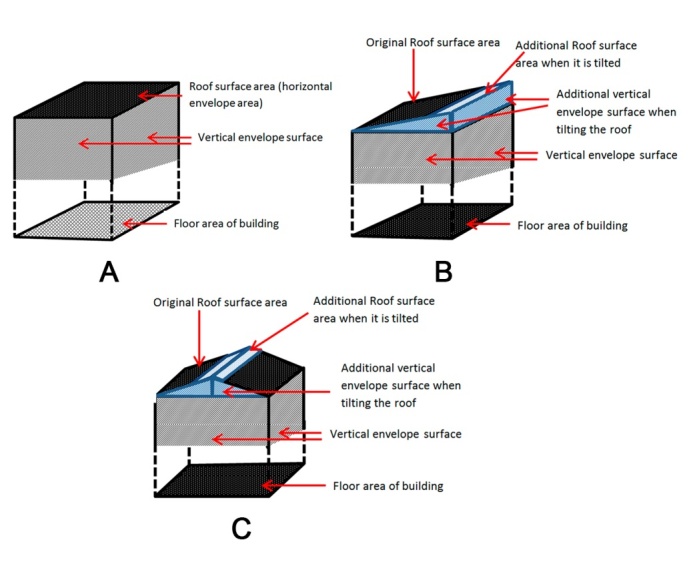

- In order to study the response of each factor, three possible reductions of compactness have been studied:(1) The variability that can occur with the floor plan (when the proportionality of its sides varies from 1:3 to 3:1, passing 1:1, i.e. a square base Prism – Fig. 1) as well as when there is a sectional break, increasing the perimeter (see Fig. 2).(2) The effect of extending an isolated house to a building of 3 or 5 floors and then taking into account the intermediate apartment.(3) The case of a building project with a sloping roof. In this case, a reduction of compactness has been considered for the mono-pitched roof and the dual pitched roof or gabled roof (Fig. 3). This has been studied for each case, when the inclination is 10° (almost 2:12), 30° (near 6:12), 45° (12:12) and 60° (near 3/2 – typical for snow sliding roof).In Fig. 4a, the roof surface and vertical envelope surface is indicated as part of Envelope Surface Area. In Fig. 4b, a scheme of a building is shown with a mono pitched roof. Additional roof surface and walls (side surfaces) are indicated; and, the increase the envelope surface of the building for the same floor surface of the building of case is shown in Fig. 4a. Fig. 4c shows the additional surfaces that appear when the roof is inclined with two gables.

| Figure 1. Proportionality of the floor plan varying from 1:3 to 3:1 with a = 9 m |

| Figure 2. Variation in floor plans when there are sectional breaks which can generate more vertical envelope surface |

| Figure 3. Mono-pitched roof and the dual pitched roof or gable roof from 10° to 60° |

| Figure 4. Prism and roof: 4A. Prism without breaks and an horizontal roof, 4B. Building with mono-pitched roof, 4C. Building with dual-pitched roof or gable roof |

3. Results

- Figures 5 through 8 show the behaviour of the CF, LC, CI and SF factors for each case study and demonstrate the response offered in different situations of lack of compactness.Fig. 5 shows how the CF-Compactness Factor varies if the floor plan is sectioned (Fig. 5a); when there is more than one floor (Fig. 5b); or, when there are inclined roofs (fig. 5c and Fig. 5d).

the CF value results in 0.72 m-1, which is a contradiction.The same applies to gabled roofs (see Fig. 5d). The CF values indicate more compactness when the inclination is higher. For example, for a building with b/a = 1; Ac = 81 m2, and with a floor plan without sections, the CF = 0.78 m-1. When we placed a sloping roof at 60° on the same building, the CF = 0.54 m-1, which would indicate greater compactness and is a mistake.Fig. 6 shows the variability of CL – Characteristic Length in each case considered. Fig 6a shows that by increasing the floor area (increases b/a), the compactness increases when the CL is increased. It is observed that for a prism without breaks CF = 0.8 (minimum compactness) for Ac = 27 m2 and up to CL = 1.6 for Ac = 243 m2, which implies high compactness.

the CF value results in 0.72 m-1, which is a contradiction.The same applies to gabled roofs (see Fig. 5d). The CF values indicate more compactness when the inclination is higher. For example, for a building with b/a = 1; Ac = 81 m2, and with a floor plan without sections, the CF = 0.78 m-1. When we placed a sloping roof at 60° on the same building, the CF = 0.54 m-1, which would indicate greater compactness and is a mistake.Fig. 6 shows the variability of CL – Characteristic Length in each case considered. Fig 6a shows that by increasing the floor area (increases b/a), the compactness increases when the CL is increased. It is observed that for a prism without breaks CF = 0.8 (minimum compactness) for Ac = 27 m2 and up to CL = 1.6 for Ac = 243 m2, which implies high compactness.3.1. The Relationship between SF and the Construction Costs of a Building

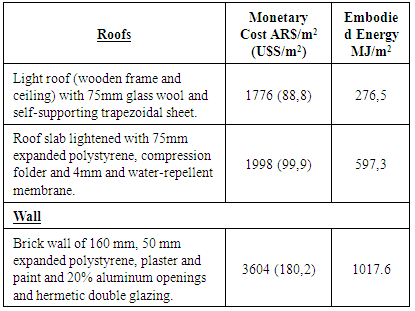

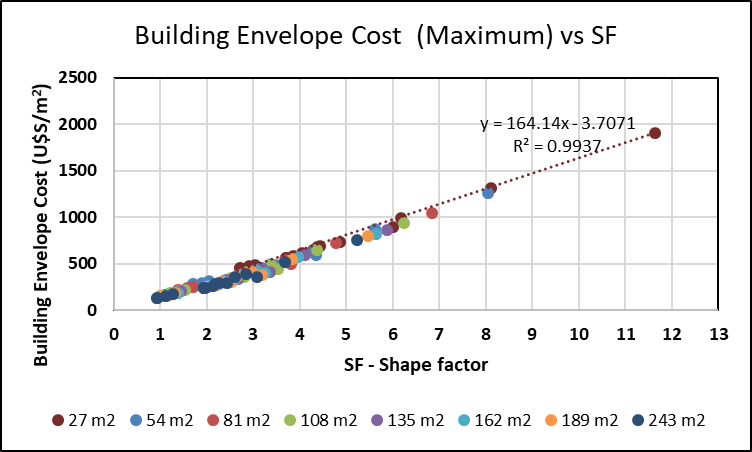

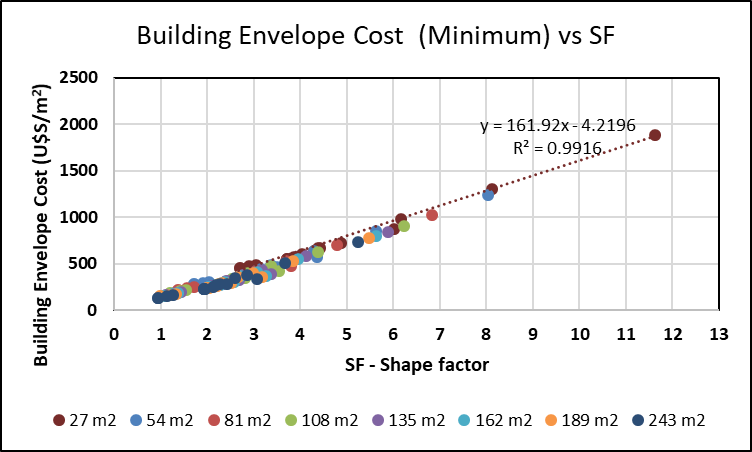

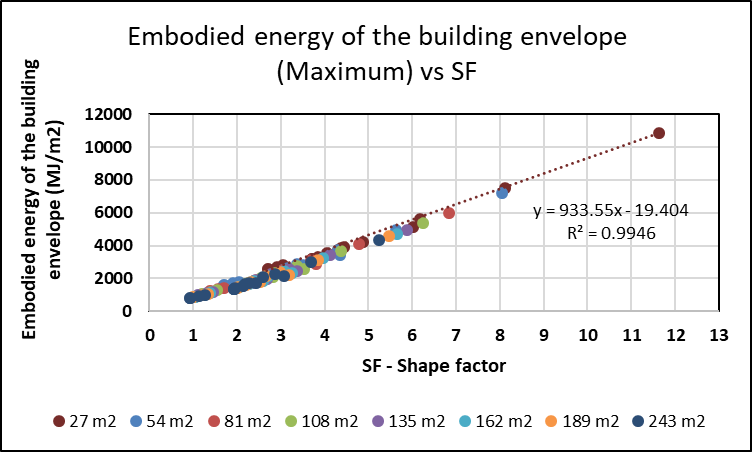

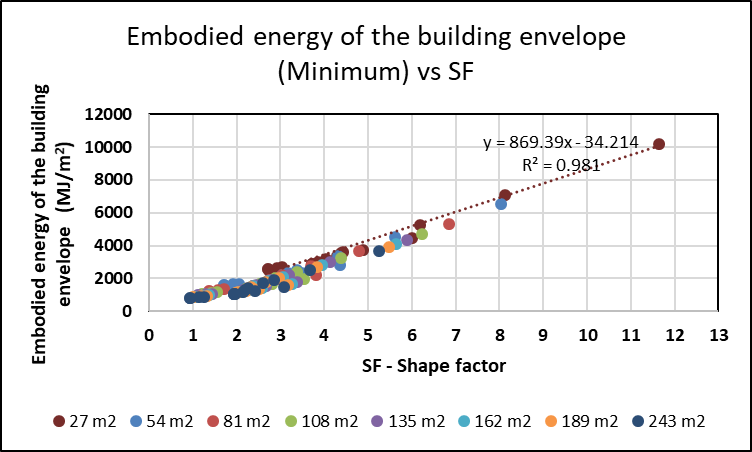

- The SF helps architects and researchers to evaluate the economic and energetic conditions of a building’s envelope. When the cost of the building is considered in relation to the floor area, it is possible to calculate how the cost (economic or energetic) of the building’s envelope can be developed in relation to the conditioned floor area for different shapes. The construction materials of the most common walls and ceilings in the Central-Western region of Argentina have been studied (see Table 1) in terms of economic costs (in U$S/m2) and energetic demands (in MJ/m2).

|

| Figure 9. Building envelope cost (maximum) vs SF for different sizes of floor area of a building |

| Figure 10. Building envelope cost (minimum) vs SF for different sizes of floor area of a building |

|

| Figure 11. Embodied energy of the building envelope (maximum) vs. SF for different floor areas of a building |

| Figure 12. Embodied energy of the building envelope (minimum) vs. SF for different floor areas of a building |

|

4. Conclusions

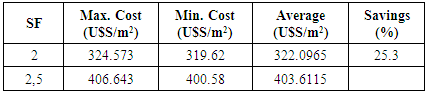

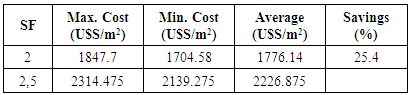

- When the building is located in temperate, cold or very cold climates, the shape and the thermophysical properties of the building envelope materials are mainly responsible for the heat losses of the building.The shape of a building is very important because it determines the cost of the envelope and the amount of embodied energy required in addition to the operation of the building.Architects and building designers have a critical environmental responsibility to protect us from the harmful emission of greenhouse gases during the entire life-cycle of the building.The SF factor evaluates the role that the shape of the building may have in the operation of environmental protection in a very easy manner. In this investigation, it have been analysed the different factors that have been proposed for evaluating building shape for efficiency through sustainable architecture. This paper considers different situations of compactness of both the area of floor plan and the volume. The results that have been obtained indicate the following:(1) Compactness Factor (Ae/Vc) responds to the compactness of the area of a floor plan and/or volume as long as there are no inclined roofs because their presence is not proportional to the desired result.(2) Characteristic Length (Vc/Ae) has the same properties as CF, so that it is only applicable against the compactness of a floor plan and/or volume as long as there are not inclined roofs. (3) Compactness Index: analyses the perimeter of a floor plan in order to evaluate compactness in relation to energy efficiency. This factor does not respond to the number of floors of a building, whether it has more than one level, nor when a building has tilted roof.(4) Shape Factor Ae/Ac: This factor provides information regarding the lack of compactness of a building. It takes into account the amount of envelope surface area for each floor. This is fulfilled both in the evaluation of the compactness of the floor plan and for the volume of buildings with horizontal or one-pitched roofs or gabled roofs.Consequently, the SF is a step forward because it enables the calculation of how the building shape impacts energy efficiency in relation to the building envelope. The value between SF = 1 and SF = 2, has been shown to be a very efficient value; however, this may vary depending on the floor area.In the construction of massive houses, the knowledge of the FAEP is very useful in order to obtain the best design. For example, if we compare one building that has an FAEP = 2.50 m2/m2 with another with FAEP = 2.00 m2/m2, the financial and energetic saving between them reaches 25%. This is done by using the same resources of a building envelope of 4 units, so that one can build 5 units in a similar project.This investigation also analyses the costs of construction by taking into account the different analysed building shapes. This paper correlates the data concerning building shape with the cost of the construction of the envelope in order to propose the SF. As a result, this paper reinforces the possibility of using the SF as a determining component for predicting the efficiency of building shape and consequently the costs of the construction, both economically and energetically.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank CONICET and the University of Mendoza for partially financing this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML