-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2018; 8(2): 39-50

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20180802.01

Outlining Subtext and Characteristics of Home in Lagos, Nigeria

Ekhaese E. N., Izobo-Martins O. O., Ediae O. J., Anweting Patrick

Department of Architecture, School of Environmental Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ekhaese E. N., Department of Architecture, School of Environmental Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This Research studied the various opinions people living in Lagos have about home in it true nous. Home generally can be a socio-cultural, psychological and ideological construct. Home means different thing to different people and can be interpreted along cultural and religious line. Therefore focus of the paper is to explain the connotation and characteristics of home in Lagos, in order to identify indicators that may define a Home. The study use triangulation, involving qualitative and quantitative method that relied on focused group interview guide, questionnaires distributed amongst residents currently residing in Lagos, Nigeria and inference statistics. The findings presented two important indicators of subtext and characteristics that were based on Psychological and Socio-physical backgrounds. The research results revealed that a broad-spectrum template framed and used to underscore significance and characteristics of home, for residents in major Nigeria cities (Lagos, Port Harcourt, Abuja, Benin, Jos, Calabar etc.) with little or no variance to the outcomes, the difference in culture and ideology notwithstanding.

Keywords: Outlining Home, Subtext of Home, Characteristics of Home, Home in Lagos

Cite this paper: Ekhaese E. N., Izobo-Martins O. O., Ediae O. J., Anweting Patrick, Outlining Subtext and Characteristics of Home in Lagos, Nigeria, Architecture Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2018, pp. 39-50. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20180802.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Home has been argued over time as an element of ideological construct. Others arguments however suggest that the home cannot be adequately understood in terms of “taxonomic generalizations” (Lima, et al, 2015). “Home is not just a matter of feelings and lived experience but also of cognition and intellectual construction people may have a sense of home even though they have no experience/memory of i” (Lind, & Cresswell, 2005). Home is a dwelling-place used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for an individual, family, household or several families in a tribe. It is often a house, apartment/ building/ alternatively a mobile home, houseboat, yurt or any other portable shelter (Mahadevia, Liu, & Yuan, 2012). Homes typically provide areas and facilities for sleeping, preparing food, eating and hygiene. Larger groups may live in a nursing home, children's home, convent or any similar institution. Homestead also includes agricultural land and facilities for domesticated animals. Where more secure dwellings are not available, people may live in the informal and sometimes illegal shacks found in slums and shanty towns (Hardoy, & Satterthwaite, 2014). "Home" may be considered to be a geographic area, such as a town, village, suburb, city, or country. A house is a building that functions as a home for humans ranging from simple dwellings such as basic huts of nomadic tribes and the improvised shacks in shantytowns to complex, fixed structures of wood, brick, or other materials contain plumbing, ventilation and electrical systems (Nasiali, 2016). Most conventional modern houses in Western cultures will contain a bedroom, bathroom, kitchen or cooking area, and a living room. In traditional agriculture-oriented societies, domestic animals such as chickens or larger livestock (like cattle) may share part of the house with humans. The social unit that lives in a house is known as a household (Easthope, 2004). Most commonly, a household is a family unit of some kind, although households may also be other social groups or individuals. The design and structure of the house is also subject to change as a consequence of globalization, urbanization and other social, economic, demographic, and technological reasons (Castles, De Haas, & Miller, 2013). Various other cultural factors also influence the building style and patterns of domestic space. It is certain that various people have their different views and perception of what a home is and its characteristics based on varying factors; the type of houses they live in or their environment (Andrews, & Withey, 2012). It against this backdrop, the study has highlighted the various issues that relate to home. Therefore, the focus of the paper is to examine the meaning and characteristics of home in Lagos, in order to identify the key misconceptions associated with Home.

2. Study Area

- This research will however be reviewed in the context of contemporary Nigerian culture using Lagos as a case in point. While the growth of the population in the metropolitan Lagos has assumed a geometrical proportion, the provision of urban infrastructure and housing to meet this demand is, not at proportionate level (Ogunnaike, 2017). This has resulted in acute shortage of housing to the teeming population with Lagos alone accounting for about 5 million deficit representing 31% of the estimated national housing deficit of 18 million (Olugbenga, & Adekemi, 2013). The extent of the housing shortage in Lagos is enormous. The inadequacies are far-reaching and the deficit is both quantitative and qualitative; even those households with shelter are often subjected to inhabiting woefully deficient structures as demonstrated in the multiplication of slums from 42 in 1985 to over 100 as at January 2010. The urban poor, who are dominant in Lagos, are transforming the city to meet their needs, often in conflict with official laws and plans (Agbola & Falola, 2016). They reside in the slums and squatter settlements scattered around the city and are predominantly engaged in informal economic activities which encompass a wide range of small-scale, largely self-employment activities. 60% of residents are tenants and have to pay rent as high as 50-70% of their monthly incomes since most of the existing accommodations are provided by private landlords (Opoko, & Oluwatayo, 2014). The concentration of housing and income levels has stratified the metropolis into various neighborhoods of low income/high density, medium income/medium density and high income/low density (Lawanson, 2012).

| Figure 1. Graphics of Lagos, Nigeria |

3. Conceptual and Theoretical Overview

- The early man, made use of caves which served as a shelter against elements of the weather, in areas where caves could not be located, rudimentary shelter was constructed using available materials (Flannery, 2012). For nomadic societies whose existence depends on hunting and food gathering, and frequently moved from place to place in search of food, they had no permanent shelter, hence their homes moved along with them. Communal homes were used by societies or large families with relations settling in a place which usually shares public utilities. Land in this case was owned by the community. Individual homes are usually permanent dwellings which came about as a result of people owning individual properties to call their own which as a result led to the urban setting (Makinde, 2014).

3.1. Theory of Home

- The meaning of home/“dwelling” have been studied from different perspectives by various people. Fox, (2002) state that home studied from various views, this includes Architectural, sociological, psychological and environment-behavior and archeological based studies. The meanings of home can be derived from perceptions, age, cultural and economic factors. Home may be located in a house, but a house may not necessarily mean a home (Mallett, 2004). It could be permanent/temporary and may exist in separate locations for different individuals (i.e. a home away from home). Home in the sense of territory is a place where one can be independent, be in charge and take control, even if it is only perceived control, which means the extent to which one believes what happens is a matter of fate, one’s own powerlessness, versus a belief that one is the master of one’s own destiny (Ross, & Mirowsky, 2013). Home can also be an emotional attachment to a physical environment where an individual’s memories and experiences are created, which in turn provides a basis for self-identity (Scannell, & Gifford, 2010). It is a place of rest, privacy, refuge which provides its inhabitants an envelope or boundary which separates it from the exterior world. It serves as a point of origin or as a reference to the past. Home could also be referred to as a physical space that the inhabitants are familiar with intimately which provides a sense of security to enable its inhabitants develop routines in order to carry out everyday activities. Home imparts a sense of identity, security, and belonging (Premdas, 2011).

3.2. The Concept of Home, Place and Space

- In the humanistic geography space and place are important concepts (Simonsen, 2013). These concepts in this case don’t have the same meaning. Space is something abstract, without any substantial meaning. While place refers to how people are aware of/attracted to a certain piece of space. A place can be seen as space that has a meaning. The underlying theory for this way of thinking is the phenomenology, which tries to find the essential features of experiences in the direct and indirect experiences. Great thinkers gave contributions in defining space, place and the differences between these concepts. The same ideas about the distinction between space and place and searched for meaning of place, space and environment. According to Hall, & Page, (2014) the difference between “space” and “place” can be described in the extent to which human beings have given meaning to a specific area. Meaning can be given/derived in two different ways, namely: In direct and intimate way, i.e. through the senses such as vision, smell, sense and hearing, and in an indirect and conceptual way mediated by symbols, arts etc. (Hall, & Page, 2014). 'Space' can be described as a location which has no social connections for a human being. No value has been added to this space. Karsten, (2005) believes that it is an open space, but may mark off and defended against intruders. It does not invite or encourage people to fill the space by being creative. No meaning has been described to it, it is more or less abstract. 'Place' or the contrary is more than just a location and can be described as a location created by human experiences (Cresswell, 2014). The size of this location does not matter and is unlimited. It can be a city, neighborhood, region or even a classroom et cetera. In fact “place” exists of “space” that is filled with meanings and objectives by human experiences in this particular space. Places are centers where people can satisfy their biological needs such as food, water etc. MacCannell, (2011) agrees that a “place” does not exist of observable boundaries and is besides a visible expression of a specific time period. Examples are arts, monuments and architecture.

3.3. Environment-Behaviour Studies on Home Environment Satisfaction

- The scope of environment-behaviours’ concerned include, use of resources, creation of waste, health and wellbeing, performance and productivity, crime, and security. These can run for years given the expected lifetime of a building. Human element and the way it affects other aspects of the system can be unpredictable, particularly when timescales are long and the system is complex and open-ended. The interrelationships between home design and human behaviour, are disjointed and spread across professions, disciplines, workers at different stages in the lifecycle of buildings and academia/practice. Architects, designers, engineers, facilities managers and building users all have different experiences and have accumulated different knowledge that can be broadly applied, and some is well-verified. Knowledge within built environment disciplines exists beside a growing body of behavioural theory and experience in behavioural science application to policy-making process (Cabinet Office & Institute for Government 2010), Conveying the relationship data between design and behaviour from built environment professions, along with behavioural theories emerging from psychology and other social science disciplines, has the possibility to deepen characteristic of home. Designing for end-users, a good home design needs to embrace well established ‘inclusive’ or ‘universal’ design principles (British Standards Institute 2005). Principles of Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (2006) propose that inclusive design- places people at the heart of the design process, acknowledges diversity and difference, offers choice where a single design solution cannot accommodate all users, provides for flexibility in use and provides buildings/environments that are convenient and enjoyable for everyone to use. The beliefs is that inclusive design is user centred, population-aware and good for business (University of Cambridge & BT 2013). The built environment should be similarly designed to meet the needs, capabilities and aspirations of all potential users (CA & TBE 2008). The home, the built environment and the user together form a system (Clarkson, & Coleman, 2015), There is sign that home designed to be inclusive are popular with all users (UC, Department of Engineering 2005). Users are expected to behave in a certain way if the impact of doing so is clear, immediate and if the default option is the desirable behaviour. Users prefer to be in control of their lives, as well as their work environment. They favour empowerment to ‘command and control’. Human behaviour in complex systems is habitual, repeated and quick decision-making result that is not subject to careful analysis (Kahneman, 2013). Once entrenched, a habit is hard to change although, with time, habits can be erased. There are specific points when behaviour is more likely to change (Thompson, et al 2011). This is a way behaviours are nested in each other, rather than determined in isolation. The design of the built environment in association with social factors equally support how people behave and feel (Cabinet Office and Institute for Government, 2010). An understanding of how the built environment design along with other factors/policy interventions, can influence behaviour in a positive way would benefit both policy and practice (Thaler, & Sunstein, 2009, De Ridder, 2014). Experience has shown that needs and behaviour of users cannot be designed into a system at a late stage because system design choices are almost always constrained by earlier choices. This means that user behaviour needs to be considered during the development of the design brief, making behavioural assumptions clear very early in the process, and opening them up to analysis and challenge. For home design carrying out testing using mockups, prototypes and simulations will create financial cost but reduce failure risk (UCL and DoT 2008). However, if human behaviour is fused into the process of identifying and managing risk, the probability of un-satisfaction can be reduced (Gill, & Spriggs, 2005).

3.4. Human Interactions with the Built and Natural Environment

- Understanding interactions between design and human behaviour is a key factor in creating, operating and maintaining a successful built environment that supports resource stewardship, health and wellbeing, and performance and productivity (Cole, Oliver, & Robinson, 2013). A useful approach is to consider buildings and the people who use them as parts of a complex system. Systems thinking is described as holistic, total, joined-up, socio-technical, or user-centred thus requires multidisciplinary collaboration, since no single discipline, profession or stakeholder group has all the necessary expertise to tackle the whole system (Meyer, 2014). Systems thinking complements the detailed knowledge that stakeholders may have of individual components, and helps to identify how different parts of the system interact, and what developing characteristics it may have. There is a great deal of evolving knowledge about the factors that influence behaviour but much of it is fragmented across disciplines. The knowledge of built environment professions could be brought together along with initial knowledge about behavioural theory to provide a more inclusive accepting of the relationship between design of the built environment and behaviour. Interdisciplinary approaches to design that allow knowledge to be used should be promoted through education and best practice (Greenhalgh, & Wieringa, 2011). Funding is however needed to strengthen the data base by means of post-occupancy evaluation and other types of research, and develop practical, evidence-based tools. A systems approach to design, and the built environment is helpful. More work is needed to identify how this approach can complement or add to existing best practice, along with the development of practical tools. Suggestion should be sought on how the design of the built environment, alongside other factors or policy interventions, mutually reinforce behaviours that lead to improved stewardship of resources, health and wellbeing, and performance and productivity (Arthurson, 2012). Despite the understanding of interrelations between home design and environmental behaviour and human interactions, there are several potential barriers to be consider. These includes- cost, resource, time, and lack of knowledge, current practice and the expectations of key stakeholders. There is a need to demonstrate and justify the value of using a behavioural approach beyond avoiding failure later in the lifecycle of a building and beyond the understanding of human behaviour that architects, engineers and designers already have. The wider benefits and opportunities particularly for meeting policy challenges also need to be demonstrated. One major barrier is that there is no single agreed model of human behaviour that can be used in a design project. Furthermore, some of the most widely used models are criticised for being too individualistic and static, and so lacking in appreciation of context.

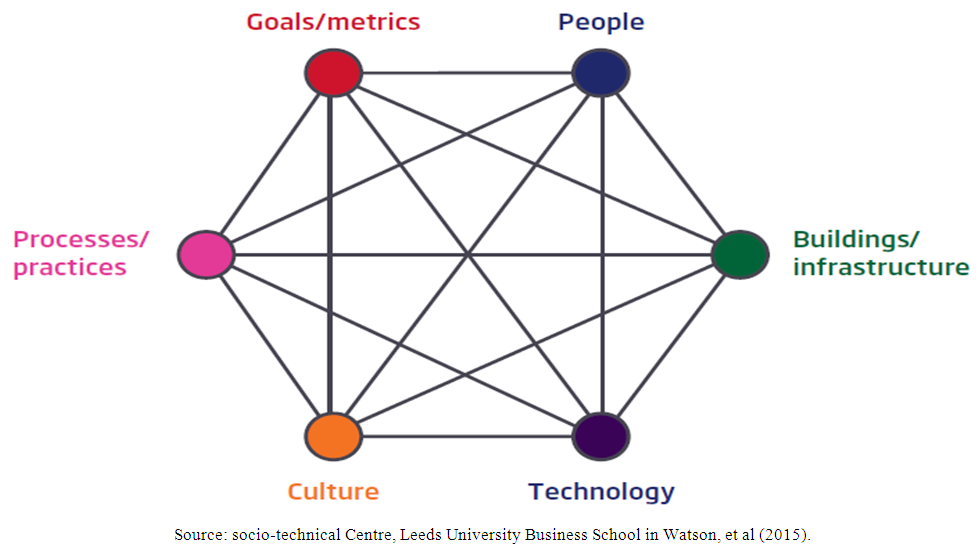

| Figure 2. Socio-technical system illustrating the interrelated nature of an Organisational system |

3.5. Categories of Home

- The characteristics and features of an ideal home can be viewed from various aspects as earlier stated. For the purpose of this paper, the Socio-cultural and Socio-physical characteristics will be considered: Psychologically home should be inviting to anyone living in and viewing it. Visual pleasure is a major characteristic of an ideal home (Hobfoll, (2001). Physical features like aesthetics and cleanliness however are also a major boost to this psychological feeling of being welcome. Home as hearth connotes the warmth and coziness which home provides causing comfort and ensuring a welcoming and homely atmosphere for others (Ringel, 2017). In other words, the welcoming feature in a home is not limited to a physical building, rather is a feeling of being welcomed that “make a house a home” for people living in the house on a usual basis. An ideal house should be safe for its inhabitants. This can be achieved by the physical elements placed (Michie, et al 2011). The rooms in the house should be planned well as all areas utilized in connected activities near to each other. The kitchen should be near the dining room to allow foods being served easily during mealtime, The living room should be near the dining room to allow the guests to be served easily during meal time, The bathroom should be adjoined to the bedrooms for personal necessities, The washing area should be positioned at the back of the house so that the clothes will be hanged in the clotheslines with relative ease, Rooms in the house should spacious enough, There should be wide enough windows for proper ventilation and lighting that might contribute to the family’s good health, It should have sufficient supply of water for tasks such as laundering, bathing and other personal needs of the family, Work Areas should be planned to prevent crowded space (Schaaf, Toth-Cohen, Johnson, Outten & Benevides, 2011). The rooms should also give a sense of Intimacy and ease. Socio-Physically home should have some personal items that reflect you and/or your family. It should be clean without being pristine (Cohen, N. (2013). An idyllic home should meet the physical and social needs of the family. It must be equipped with: kitchen, dining, Bedroom, bathroom, living room, garden and lawn and children play area. In environment-behavior studies, the following ten general categories of Home often occur (Prayag, & Ryan, 2012): Home as security and control, Home as reflection of one’s ideas and values, Home as acting upon and modifying one’s dwelling, Home as permanence and continuity, Home as relationships with family and friends, Home as center of activities, Home as a refuge from the outside world, Home as indicator of personal status, Home as material structure: Categories according to material structure, the various examples include: Apartment, Condominium, Cottage, Townhouse, Single-family detached home, multi-family residential dwelling, Duplex and so on (Wells, Evans, & Cheek, 2016).

3.6. Idea of Home to Nigerians

- What does a home mean to Nigerians? Pretty much everything, it turns out. World Remit, a digital money transfer service, asked Nigerians all over the world about the things that made them think of home. They wanted to find out how Nigerians feel about where they come from and what keeps them in touch with the places they are now. Countless number of answers was received and they couldn’t have been more different. Home, a simple four-letter word, yet everyone have their own ideas of what it means (Saguy & Ward, 2011). Sometimes it was the sounds, smells and tastes of where you came from, but the most common answer of all was family, a photo of your grandparents – comfort, joy and memories of a life shared (Poulos, 2016). “My home is my kids”, said one of the customers. Family reminds us of home, a place where we are among kin. But home doesn’t have to be Lagos or Ibadan. For many Nigerians living abroad, Nigeria isn’t the only place on their mind. Home is playing soccer in the U.S, eating ice cream in the UK, and getting used to the snow and the cold in Switzerland. When life couldn’t be more different from Sokoto or Kaduna, Nigerians everywhere have found new places they call home. Generally, a people’s culture affects the types of homes they live in. Home must be accommodating, calm, and in a “respected” area. For example, Edos, Nigeria believe that the homes should be sacred, a cultural symbol, respected and used wisely. Some houses are built with bigger and additional spaces as a result of different cultures. For instance, the Igbos in Nigeria believes that one needs to erect four/more buildings in one compound in one’s native town to accommodate large families. The home is people and a person is home Fossey, et al, 2014). The relationship between people and home is sacrosanct. Whether a house is occupied by a person or ten persons, the state of the home is affected either in positively/negatively. Each year, Nigerians welcomes thousands of people to the country and majority of this population bring their different culture and beliefs and expectations on their homes too (Wilson, Houmøller, & Bernays, 2012). The homes are a product of what each individual wished it to be. In conclusion, culture and home work hand in hand and the home is deeply affected by materials, beliefs, environment, traditions and diversities (Durand, 2011).

3.7. Home and Place Attachment

- Home attachment has to do with bonding of people to places, which can be functional attachment and emotional attachment (Anton, & Lawrence, 2014). People tend to build homes in places that meet their needs, both physical and psychological, and match their goals and lifestyle. Research indicates that the strongest influence upon an individual’s place attachment is the length of residence in the area. The longer a person lives in a particular area, the more positive the sentiments toward the community are likely to be. An individual is most likely to feel attached to a place where they have many local friends and relatives and where there are long term residents in the area (Scannell, & Gifford, 2010). There are indications that an individual is more attached to the people associated with a place than to the place as a physical entity. This refers to the ability of home and place to enable us achieve our goals and desired activities. If there is an ongoing relationship with a place and it supports our highly valued goals and activities, then there will be an attachment to the place. Emotional home and place attachment has to do with the feelings, moods and emotions people have about certain places Wiles, et al., (2011), Points out, that people can relate to home itself and the communities defined by it. Place attachment is seen as a good thing by commentators. Seligman, (2004) noted that emotional place attachment certainly has a strong positive effect in defining our identity, in filling our life with meaning, in enriching it with values, goals and significance thus contributing to our mental health and well-being.

4. Research Methodology

- A total of 250 questionnaires were distributed to ascertain the various perceptions people living in Lagos have about what a home really means. The paper provides a description of the research methods used in data collection and analysis. Research was design to include focused group interview through a semi structured interview guide and qualitative narrative was also employed, questionnaires was use to elucidate information from residents of Lagos, Nigeria as well as observation. Therefore triangulation method was used to expound the required facts for the research. The questionnaires were circulated among different household in Lagos. 249 were filled and returned. It covered areas on general section, and attitudinal questions section.

5. Findings and Result

- The findings and results were presented, analyzed and Interpreted along the line of data collated from the questionnaires shared and observations made. A critical analysis on meanings and characteristics of home in terms of what people living in Lagos think was revealed. Basic mediums of Representation are Descriptive Statistics (Tables, Frequencies and Charts). SPSS was used to analysis the data collected through the instrument (questionnaires).

5.1. Psychological and Socio-Physical Characteristics of Home

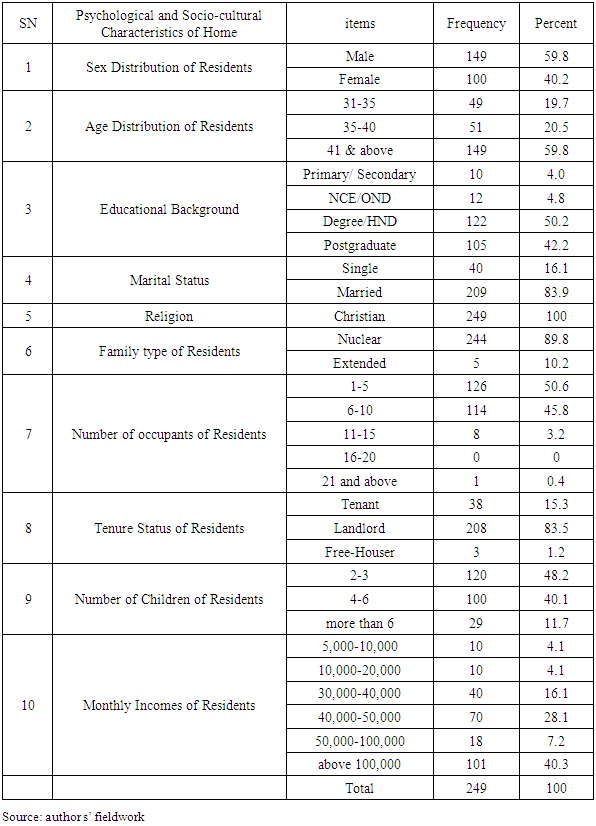

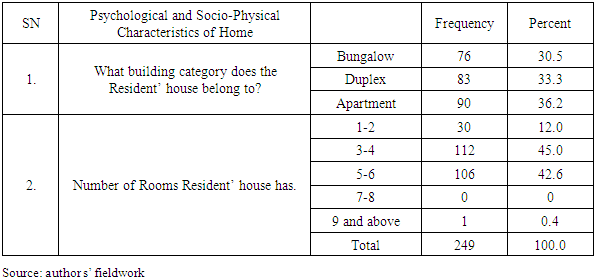

- The data collected through the use of questionnaires according to the different psychological and Socio-physical characteristics of home in Lagos are as interpreted below as shown the various tables. Table 1 showed that there were more Male (59.8%) respondents than Female (40.2%). This variation was because at the time of sharing the questionnaires, the people around were mostly male. The data collected however showed that most of the male respondents were completely supported by friends, family and partners in times of family conflicts or challenges. This reveals that psychologically, their houses can be called homes viewing its psychological values. The female respondents, however mostly replied to a moderate level of support from friends, family and partners as shown in Table 1. Most of the residents were above 41 years of age, which comprised mostly of men and women in their late 40s and early 60s. The questionnaires were shared around midday. The least number of residents had an age range of 31-35 which explained the fact that most of these people of that age range were still in rented apartments. A better understanding of what home is was explained by people who already have families. See Table 1.

|

|

5.2. Perception of Home in Lagos, Nigeria

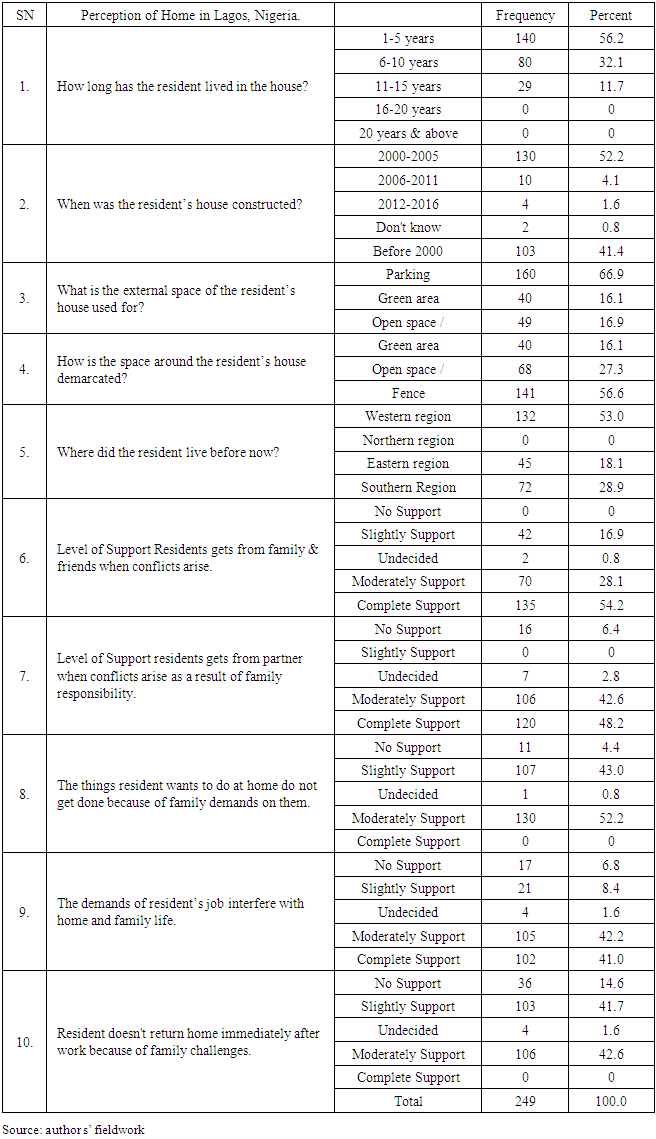

- The data on various perceptions of home in Nigeria from the distributed questionnaires are as interpreted in descriptive frequency table 3. The Number of years spent in the houses and the time or year of construction of houses was gathered. From Table 3, 140 residents alleged to have been living in the houses for up to 1– 5 years while 80 residents replied 6-10 years. The remaining (29 resident) have lived in the house for 11-15 years. Revealing that majority actually tend to relocate from the present houses but would still carry the perception of home to wherever they go. This explains the difference between space and place giving a different space meaning and eventually turning it to a ‘place’. When asked when the houses were constructed, 0.8% (i.e. 2 residents) did not know the date of construction while 103 respondents (41.4%) retorted that houses were constructed before 2000. 130 residents (52.2%) replied 2000-2005, while 10 residents (4.1%) replied 2006-2011.

|

6. Conclusions

- Home is vital tool that is necessary in a society that takes its place of importance as a building block on which the society cannot do without. Home is a dwelling-place used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for an individual, family, household or several families in a tribe. A house is a building that functions as a home for humans ranging from simple dwellings such as basic huts of nomadic tribes and improvised shacks in shantytowns to complex, fixed structures of wood, brick, or other materials contain plumbing, ventilation and electrical systems. Most conventional modern houses in Western cultures will contain a bedroom, bathroom, kitchen or cooking area, and a living room. The study has identified the meaning, perception, perspectives and characteristics of home and the key issues associated with home. The different perspectives of home has been consider in this study as residents of Lagos have both negative and positive perceptions and perspectives of what home means, usually because of historical background and past events. From following deduction reveal that the psychological, socio-cultural and socio-physical views/perspective are amongst main indicators that has shape the meaning and characteristics of home in Lagos, Nigeria. However, from this study, the following are recommendations to be incorporated into the design of Nigerian homes. When designing, the Architect should include the socio-cultural background of client in other to provide a sense of intimacy that should link to the Cultural background. This can be achieved by using features in the home like finishes, arrangement of spaces, spaces sizes used, furniture and house furnishing, façade of the house and relationship between private and public areas. The Architect should incorporate physical features and spaces to the building during the design process to ensure that the structure is an ideal home (Functional & Aesthetically pleasing). These spaces and features include-Living room, dining, kitchen, bedrooms, Bathrooms and Toilets, Store, garden, parking and other specialized spaces based on clients requirements. These spaces should satisfy the client’s physical, social and emotional needs. Therefore various perceptions people have of home reflect their background and lifestyle. This should be taken as a vital consideration during the design process of houses. Due to the fact that a family is the basic unit of a society and every family requires a home.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This paper has benefitted immensely from the financial assistance of Covenant University, Ota Nigeria. The authors acknowledge the important contribution of Wells, N. M., Evans, G. W., & Cheek, K. A. The authors are solely responsible for any errors and omissions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML