-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2018; 8(1): 12-18

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20180801.02

Challenges of the Urban Boundary Wall: The Case of Two Neighbourhoods in Accra, Ghana

Ninnette Quaofio1, J. G. K. Abankwa1, S. O. Afram2

1Central University, Miotso, Accra, Ghana

2Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Ninnette Quaofio, Central University, Miotso, Accra, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Boundary walls are constructed for safety, privacy, security, territory demarcation, among other reasons. Their construction is however raising concerns with social interaction, integration and crime control etc. in many African cities. This research is aimed at studying two neighbourhoods to ascertain the veracity of these assertions and to explore the possibilities of using the design of walls to enhance them in addition to improving the aesthetic appeal of streetscapes. The study employed the mixed method approach to gather data using survey questionnaires and face-to-face interviews with relevant stakeholders. Some key findings indicated that walls hamper social interaction and integration and do not guarantee safety and security. Recommendations made included the formation of neighbourhood watchdog associations, installation of CCTV cameras, adoption of standardized boundary wall designs and front walls that allow for views into residences.

Keywords: Walls, Boundary wall, Neighbourliness, Cityscapes, Urban degeneration, Social interaction

Cite this paper: Ninnette Quaofio, J. G. K. Abankwa, S. O. Afram, Challenges of the Urban Boundary Wall: The Case of Two Neighbourhoods in Accra, Ghana, Architecture Research, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 12-18. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20180801.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Throughout history, cities have used walls to demarcate boundaries, provide safety, security and protection from enemies (Weizman, 2007). Boundaries including walls for privacy, boundary marking wall and city walls in general, are commonly identified in many known societies as a barrier to prevent progress or entry. The barrier separating Israel and Palestine, known also as the separation wall, the security measure, the fence, or a myriad of other terms was constructed as an obstruction to the intrusion of terrorists entering into Israel from the West Bank (Weizman, 2007).The reason for building the Great Wall of China for example, was to protect the Chinese Empire from Mongolian invaders as well others but for a long time it was an object of fascination for foreigners (Li, X., & Wang, Y, 2011). The wall is now a revered national symbol and a famous tourist destination. Similarly, The Kano city ancient wall, a historic structure as well as a monumental edifice built to guard the dwellers of the city at that time (Akinade, 2005). The great Zimbabwean wall built in the 14th century is another fascinating quest for city protection and authority but all that remains are ruins of which spread over a terrain of 270,000 square miles found in the region (Pikirayi & Chirikure, 2011). City walls, just like other historic buildings, revealed the aspirations, traditions and culture of the forefathers; these are inspired works of people who were never forced to conform to standard and are seen today therefore as ruins of their former glory (Adeyemi and Bappah, 2011). People have always found it important to guard themselves against the elements of their environment and from potential adversaries (people and animals) as well as to separate and pull away from the broader group. The idea of privacy as a component of the built environment has been around since the beginnings of humankind (Riley, 1999). Demarcation by clearly defining territory by groups of people has been one of the primary instinctive concerns of the early occupants of the earth to protect themselves from their enemies. Martin (2014) emphasized this when it identified that, residential walling fulfils several functions especially a form of security. To form a visible barrier for unwanted onlookers, it is also important that the walling distinguishes a home from its visible feature and give privacy.In the past decade, walls in the City of Accra have become taller, thicker, opaquer, fortified with metal barricades and security electric fence wires with very little supervision by appropriate professionals. The study explores the possibility of using the design of walls to enhance integration, safety, reduce crime and effect change to the urban environment through social interaction while maintaining aesthetically appealing streetscapes.

2. Literature Review

- When an exterior structure is made of wires, it is generally termed a fence whereas when it is made of masonry it is referred to as a wall. In newly settled lands, walls are usually built of materials easily available, for example, stone, earth, bamboo or wood (Brolin, 2000). Ellickson, (1986) also defined a wall as that which separates boundaries, keeps out people and animal trespassers, but keeps in the builder’s animals. According to Georgiou (2006), walls commonly abut public space and therefore, their design and construction must be considered because they will be seen by many people and therefore viewed in the context of a long-term corridor which helps in aesthetic planning as well as local community planning. Furthermore, they should also enhance the beauty of a building, while maintaining compatibility with the architectural style of the residence which they serve Georgiou (2006).The city of Accra is developing fast and sprawling horizontally with individuals as well as estate developers building luxury homes for their comfort. These buildings are however enclosed, sometimes almost to the point that only the roof can be seen from the street. The whole building is bordered with tall, huge, solid walls with electric fencing on top of them, with huge gates completely preventing passers-by from appreciating the aesthetics of the architectural design of the building. It is believed that this alludes to affluence and status and will also prevent any intruder or activity that is suspicious. However, the issues of walling have not been holistically integrated into the design process. It looks like emphasis has rather been put on security and privacy considerations of residents with minimal or no input by professionals and local authorities. This has however brought about some emerging issues like heights of walls and the material combinations for designs. Other security attachments to walls and supervision need to be critically examined by professionals concerned. It is upon this premise that this study will seek to look at two neighbourhoods to explore the veracity of these assertions and the possibility of using the design of walls to enhance integration, safety, reduce crime and effect change to the urban environment through social interaction while maintaining aesthetically appealing streetscapes.

2.1. Gated Communities and Private Walled Homes

- Frameworks of Walls and class division are profoundly being ingrained in historic Europe as a method for affluent individuals shielding themselves from the neighbourhood populace (Blakely and Snyder 1997; Turner 1999). However, to comprehend the requirement for a different discourse of gated communities; it is useful to first understand the difference between Gated Communities and private Walls around homes. Though Gated Communities exist as aggregate elements separate from the bigger society, walled private homes are individual plots of land largely independent from society. Meanwhile Gated Communities are often walled off with one outside wall; walled individual homes however present their own wall to prevent outsiders from accessing them.The walls talked about in this paper, then again are walls that border different individual homes from each other and from people in general. They are also associated with each other or frame some portion of bigger lodging developments.

2.2. Reasons for the Increase in Boundary Wall Construction

- The spread of walled and gated communities started in the US, for instance the underlying function was to ‘‘protect properties and to define the leisure space of retirees’’ (Low 2001, p. 45). In the 70s and since then, shut and gated neighbourhoods have found a more extensive business sector among the upper white-collar class and the working class in American urban areas, expanding officially existing enclaves and making designs that promote exclusion in the housing market (Blakely and Snyder 1997; Higley 1995; Lang and Danielson 1997). The development of walled and enclosed communities is as a reaction to the privatization and withdrawal of the state in the procurement of housing everywhere throughout the world. In most open administrations, for example, gathering of waste and security are currently given by private organizations rather than the nearby governments. Abdelhamid (2005), asserts that the fundamental purpose behind the development of gated communities is increasing crime rate. A few inhabitants choose to flee from this "dangerous" environment and live in a shut securely gated group, for instance in South Africa and in different places. Atkinson et al (2005) likewise feels that the spurring power behind the advancement of gated groups has been an apprehension of wrongdoing and a longing for improvement that is secure.

2.3. Theoretical Concepts of Walls

- Two theoretical concepts – the fear of crime and violence and privacy, security and safety – are pertinent for the emergence of the Gated Communities and Private Residence Walls in most countries including Ghana.

2.3.1. Fear of Crime and Violence

- Fear has been described as "the institutional, social and mental repercussions of wrongdoing and viciousness" and it is recognized as a result of destabilization, segregation and vulnerability (Moser, 2004:4). The life of fear of crime and viciousness are across board, both in the natural and built environment. It ought to be noted here that trepidation of wrongdoing is not the same as the impression of crime, which is the acknowledgment and information that crime happens. “Fear is an inherent part of our nature which prompts us to seek safety and security when evil or danger looms” (ibid).

2.3.2. Privacy, Security and Safety

- The term privacy is utilized every now and again as a part of conventional dialog and in philosophical, political and legitimate exchanges, yet there is no single definition or investigation or significance of the term. In this study ‘privacy’ is defined as means towards achieving security of information contained within the home both of persons and of property and it means ‘something that gives or assures protection and safeguards against external influences infringing on the well-being of the home, the occupants and the properties therein’. In this context, the concept of privacy is important as it allows one to restrict others’ access to residents and homes and enables and enhances personal expression and development of relationships with others. The concept gives protection from over-reaching social control by members of the public through their ability to get information or the possibility to have an upper hand in decision-making.

3. Research Methodology & Study Area/Setting

- A mixed approach research design was adopted to make sure that all pre-conceived ideas of the researcher are reduced considerably and make sure no ‘gaps’ exist in the information or data collected. (Bulsara, 2015) These techniques were considered to help the researcher interrogate and explain the research findings by using many subjects and questions as well as gathering data from participants who form part of the population with respect to one or more variables as well as to largely understand respondents’ perception on the effects of walls (Fowler, 1990). This is useful in order to report findings statistically as well as understand the behaviour and attitudes of respondents.Sakumono Estates (semi-detached section) was selected for this study because it was originally designed and built without boundary walls but over time over 90% of the homes have been walled by occupants with the total of 180 houses. The Trasacco estates however was also selected because it is one of the foremost, elite and exclusive gated communities in Accra. Trasacco estates consist of a total of 300 houses. The population for the research includes all people in urban boundary walled homes in the areas of study. A structured questionnaire was used to bring together information on the overall perceptions of specific components of urban boundary walls. Overall, the questionnaire for the survey consisted of fourteen (14) questions (open ended and closed ended) well organized and numbered. The questionnaire was segregated into three sections – Section A; ascertains the reason why respondents choose to stay within the boundary wall, Section B; focuses on perceptions on life within the urban boundary walled homes/neighborhood, and finally, Section C; sought to seek the general information about residents. The interview with the professional Architects was directed toward discovering why events and experiences happen the way they do, their basic nature and disposition, the who, what, and why behind them. (Sandelowski, 2000) Interviews were conducted with minimal to moderate structured open-ended individual questions. Here, the questionnaire was in two sections, (A and B). Section “A” designed to find out Architects perceptions on Security and Safety, Crime, Privacy, Social integration and interactions as well as Aesthetic appeal of streetscapes. The section B was on their socio-demographic data.A suitable sample size of fifty (50) respondents who were available in the study areas during the time of the survey was chosen. De Vos (1998:199), as well as LoBiondo-Wood and Haber (1998:253) refer to the use of readily available and accessible persons as a convenience sample in a study. Also, ten (10) qualified architects were selected for the research interview. The Architects selected for interviews had necessary information, adequate knowledge and experience in the design, supervision and the construction of these walls as they were qualified and had practiced for over 5 years, run Architectural firms and were in good standing with the Architects Registration Council.

4. Findings and Discussions

- Data from survey was analyzed descriptively with percentages and frequencies. Bar graphs and pie charts were used to provide a graphical representation of the survey data. Looking beyond the descriptive representation of the data, and to deepen the understanding of the issues of urban boundary walls, the study also developed a content analysis strategy, a fluid form of analysis of data that can be heard and seen, this directed toward summarizing the information contained in the data (Morgan, 1993).

4.1. Respondents Reasons for Staying in Walled Homes

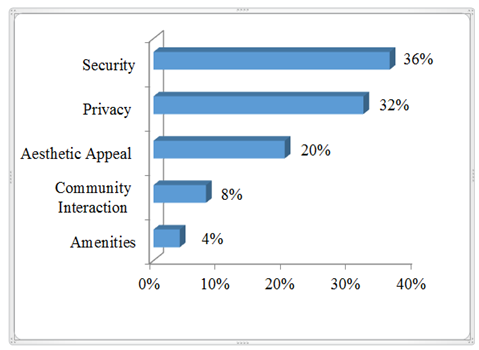

- Majority of the respondents represented by 36% indicated “Security “as the most important reason they would move into a boundary wall neighbourhood/home. The second most important reason determined was Privacy (32%) while Community Interaction and the availability of Amenities were observed as the least important being represented by 8% and 4% of the total respondents respectively.

| Figure 1. Bar graph showing the reason to stay in the boundary wall neighbourhood/house |

4.2. Life in the Urban Boundary Home (Safety and security)

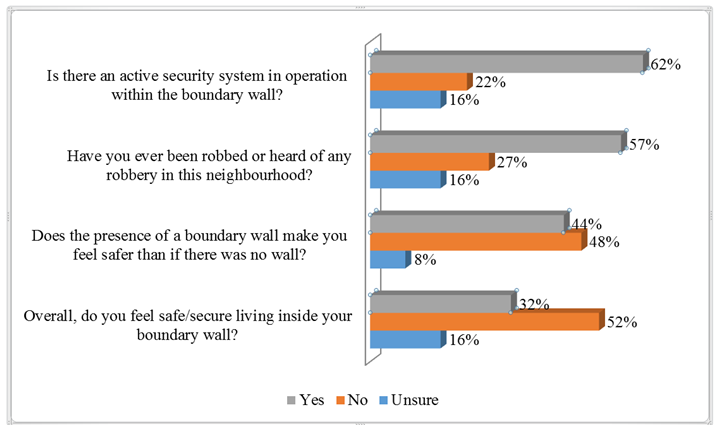

- From the findings, 78% of the respondents suggested that the presence of a boundary wall made them feel safer than if there was no wall. Additionally, as much as 62% of the respondents have active security systems in operation within their resident walls. However, the results show that more than half (~57%) of the respondents have either personally been robbed or heard of a robbery in their neighbourhood. This, perhaps, contributed to the reason why more than half (~52%) of the respondents suggested not feeling safe/secure living in a boundary wall resident.

| Figure 2. Bar graph showing respondents’ perception on security |

4.3. Social Interaction

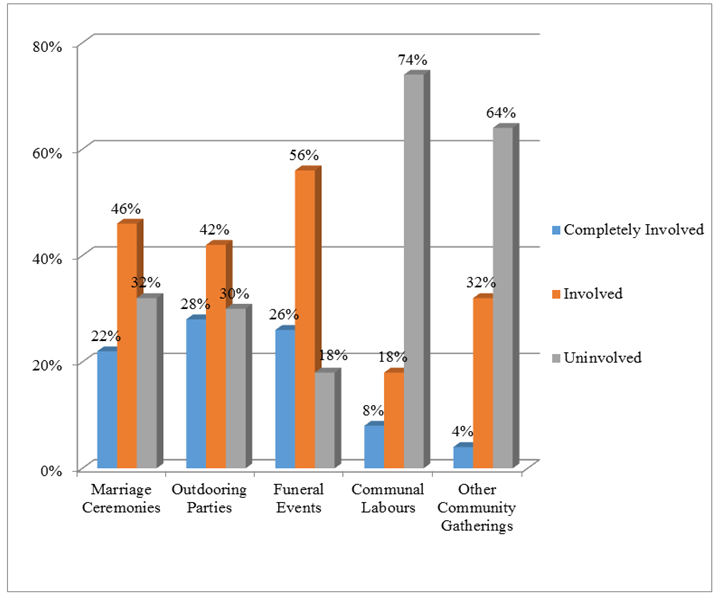

- The study identified marriage ceremonies, outdooring parties, funeral events, and communal labours among other community gatherings within the study areas.

| Figure 3. Showing respondents’ involvement in various community activities |

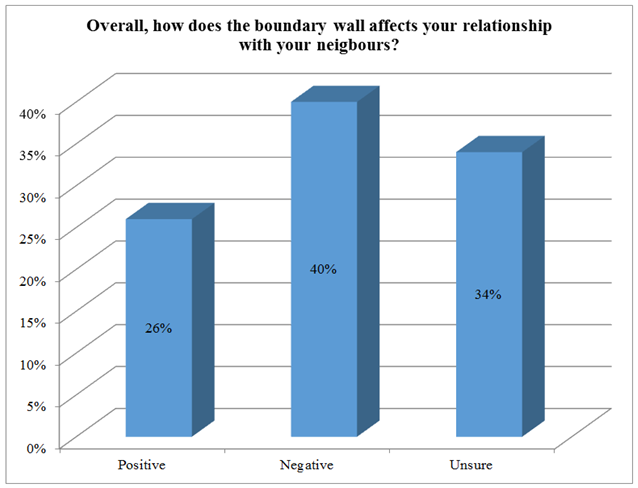

| Figure 4. Bar graph showing effect of boundary wall on Social Interaction |

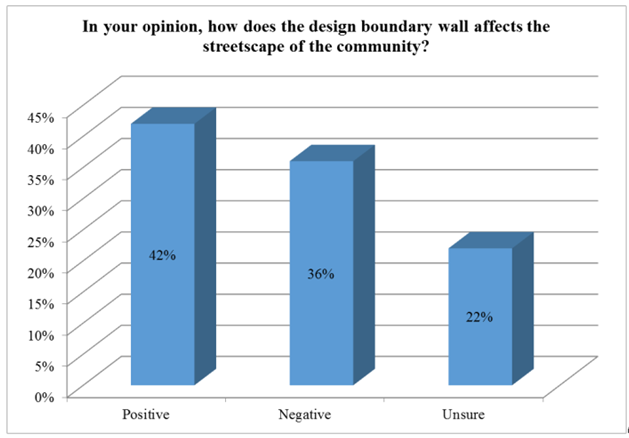

4.4. Effect of Boundary Wall on Streetscape

- From the study, though only 20% of respondents choose to live in boundary walled homes because of their aesthetic appeal, as much as 56% of the total respondents who live in boundary walls feel unique or different from other residents in the neighbourhood. Also, 42% believed the boundary wall designs had a positive effect on the beauty of the street although 22% were not sure if it did or not.

| Figure 5. Bar graph showing effect of boundary wall on streetscape |

5. Conclusions, Recommendations and Further Research

- Three common factors that determined residents’ decision to construct boundary walls around their homes included the need to protect themselves and their families from criminals and criminal activities, attacks, protection of boundaries to avoid encroachers, damage to property and unnecessary intrusion from outsiders. The reasons given could be categorized into issues of security, safety, privacy, and sense of ownership. From the discussions, security was mentioned as the most influential factor considered before the construction of boundary walls around homes.Study revealed that, walls were serving the purpose for which they were constructed, to a large extent; robberies still took place in spite of the presence of fence/residential walls. More so, social interaction and integration seemed to have been hampered seriously by construction of boundary walls which create a general feeling of isolated homes or restricted enclaves according the findings of the study.

5.1. Implications of Findings

- There are clear building guidelines for the construction of boundary walls which among others include; “Boundary wall and fences should be constructed with metal work, blockwork, adobe brick, concrete (mass or reinforced) rammed earth blocks or a mixture of any other of these certified materials and should not go up higher than 2 metres. If the front or back wall edges a road or a street, then it should be well ventilated with large openings with a gross area of not less than 45 per cent of entire surface area”. However, the study discovered that undue dominance of tall, opaque, solid residential boundary walls had a negative impact on the aesthetic appeal of streetscape and its built character. Thus, boundary walls require careful consideration in the design process. Major conclusions drawn from the research on the reasons for the increase in boundary wall construction in Accra are mainly; to prevent encroachers and to secure the boundaries of land, to satisfy the feeling of belongingness and status from research findings, the study can conclude that walls are not completely serving the purpose for which they were built, that is to prevent unwanted entry into residence and to have privacy while using home compounds. On the issues of safety, privacy, social interaction and integration as well as aesthetic appeal, the research can conclude that the above issues have been affected both positively and negatively per the findings.

5.2. Recommendations

- The study therefore recommends the following:Careful consideration be given to the design and construction of boundary walls. Architects should play a key and integral role from the inception of design phase to the construction phase so that all issues are identified and resolved successfully. It also further recommends the formation of neighbourhood watchdog associations to increase the sense of security and safety by inhabitants. The installation of street lights in front of individual homes will deter criminal activities.The adoption of more panel/chain link fence walls with sensor lights and CCTV cameras installed on them. In addition, the use of guard dogs to act as security deterrent and alert.Adoption of a combination more solid/hollow block walls or wire mesh fence interspersed with hedges or planted climbers. Lastly, the adoption of standardized boundary wall designs by communities and the subsequent submission of these designs to the various district assemblies/local authorities to act as a guide for new developments during the building permit process thus enforcing Section 17 of the 1996 National Building Regulations of Ghana, provision number four (4).Further investigations into this research topic taking into considerations a wider sample size and other conflict resolution thematic areas would be essential going forward.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML