Homan Khajeh Pour

Department of Art and Architecture and Urban Development, Islamic Azad University Najaf Abad Branch, Isfahan, Iran

Correspondence to: Homan Khajeh Pour, Department of Art and Architecture and Urban Development, Islamic Azad University Najaf Abad Branch, Isfahan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

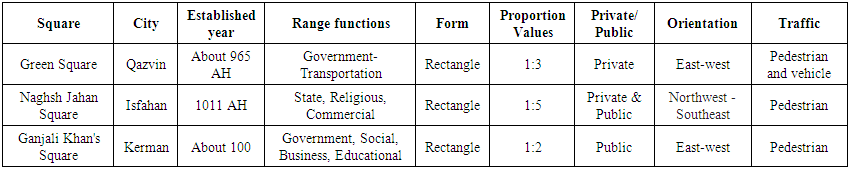

The first era of large Squares formation with geometrical structure in Iran was the Safavid era1. The study of the evolution of the Squares of this period is of great importance since many of the changes in the content, culture, and economy of the Safavid period can be evaluated by the rate and structure of these architecture elements. The city's turning points, community centers, the central foundations of the past cities of Iran and many other countries have been formed in or around squares. There is not much information about their ancient examples in Iran, but based on the influence of the squares in post-Islamic cities in Iran, it can be seen that in all periods of time there was a valuable urban structure among Iranians. In this research, we will examine three remaining indicators of the Safavid era. At first glance, we will analyze the process of formation and change over time, and then, because all three samples were built in a historical period, in terms of the form of structure and the impact of their urban cultural, economic, and social processes. We will compare their social influences. Based on the contained result, the Green Square of Qazvin has a purely governmental structure with a weak cultural and economic aspect at its time; Ganjali Khan's Square has one of the most significant cultural structures in the group, and the role of the Naghsh Jahan Square is a comprehensive example among them, due to its social and architectural aspects.

Keywords:

Qazvin’s Green Square, Ganjali Khan's Square, Naghsh Jahan Square, Historical hierarchy, Iranian Architecture

Cite this paper: Homan Khajeh Pour, Comparative Evaluation of the Formation and Social Effects of the Safavid Period’s Squares, Architecture Research, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 212-219. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20170705.03.

1. Introduction

The typological perspective studies architecture with three objectives, namely, the descriptive introduction of the construction, chronological introduction and, morphological classification. These perspectives which seek the nature of architecture in historic expansion and specific geographical environment can only consider a part of architecture, which is not the principal aspect. This is because of not choosing a deep method based on thought (Pourjafar et al. 2009: 110). Squares have been the mainstay of past urban structures in Iran, gathering social, economic, religious and political centers. The primary criteria for designing such a space were the prerequisites that were considered as religious, economic, political and recreational functions, and dictated the way in which the traditional market was formed. Combining and designing the shape of the square and the historical market in different regions and times from this angle is logical and in response to the essential urban functions. Agora, Forum, Market Square, Piatza, Plaza are different names that have been given to this similar space in different societies and despite changes in the design pattern and different cultural measures of each society they are all based on the same basic needs and concept design (Ebrahimi, 2009: 109). In turn, squares have been part of the old neighborhoods of Iran, so that from the viewpoint of some researchers (Rahnamayi et al, 2007: 23), the urban neighborhood, by integrating various environmental and social elements together, leads to the production of a sectoral structure that It identifies identifiable and independent activities, functions and collective conditions.Squares, with their aesthetic roles, affect intelligence and senses of people, leading to a positive or negative impacts on them. An architecture devoid of feeling, makes people cranky, grumpy, unhappy, primarily emotionally unsatisfied and then physically patient. It is noteworthy that the visual elements are essentially aesthetic and visual impacts of such spaces are formed through aesthetic criteria like form, geometry, proportion, range, size, order, harmony, avoiding ugliness, and pavement (Douzdouzani, Etessam, Naghizadeh, 2014:16).Accepting the need to synthesize our past with present technology, we need to examine our own roots and understand them before achieving a creative life in literature, music, painting and architecture (Fardpour, 2013: 210). The Safavid period is one of the premier examples in Iran, which can be studied well despite special circumstances. Three squires have studied in this paper contaning Qazvin’s Green Square, Isfahan’s Naghsh Jahan Square, and during the construction of the Jahan Square, Ganjali Khan Square in Kerman. These fields were located near or in the central area of the city connected to the market, and were designed to focus the entire urban structure on its central boundary. Their style of architecture is called Isfahani. According to Pirnia (2004), Isfahani style2 has these general aspects:1. Simplification of designs that are in most buildings are squares or rectangles.2. The Azeri method was constructed using a strong geometry of complex designs, but in Isfahan's style, simple geometry of broken shapes and lines was used.3. In the construction of buildings, there is no shortage (outcrop), but from this method building corners became more common.4. Also, pattern bases and sizes were used in buildings.5. The simplicity of the design in the buildings was also evident.These factors exist in many parts of the city squares, except for some parts of the Naghsh Jahan Square which attempted to create a complex geometric design due to its state structure, but in other sectors all of these conditions are fully present.Today, we have eliminated this urban element in general from the urban landscape, except for a limited number of examples that have survived from important periods such as the Safavid era, which nowadays are more of a tourism atraction than a solution to the social needs of the people of the region. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the structure of the remaining current prototype by examining the past patterns and, according to them, provide the necessary elements of the city.

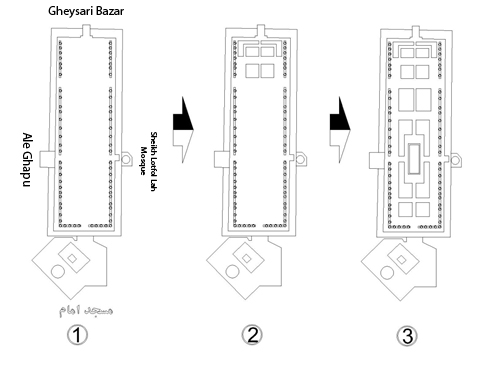

1.1. Qazvin’s Green Square

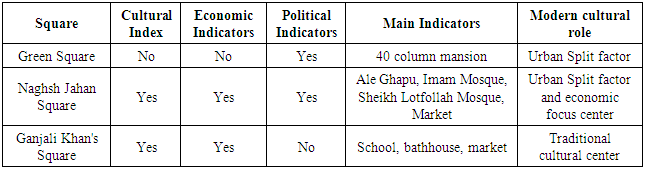

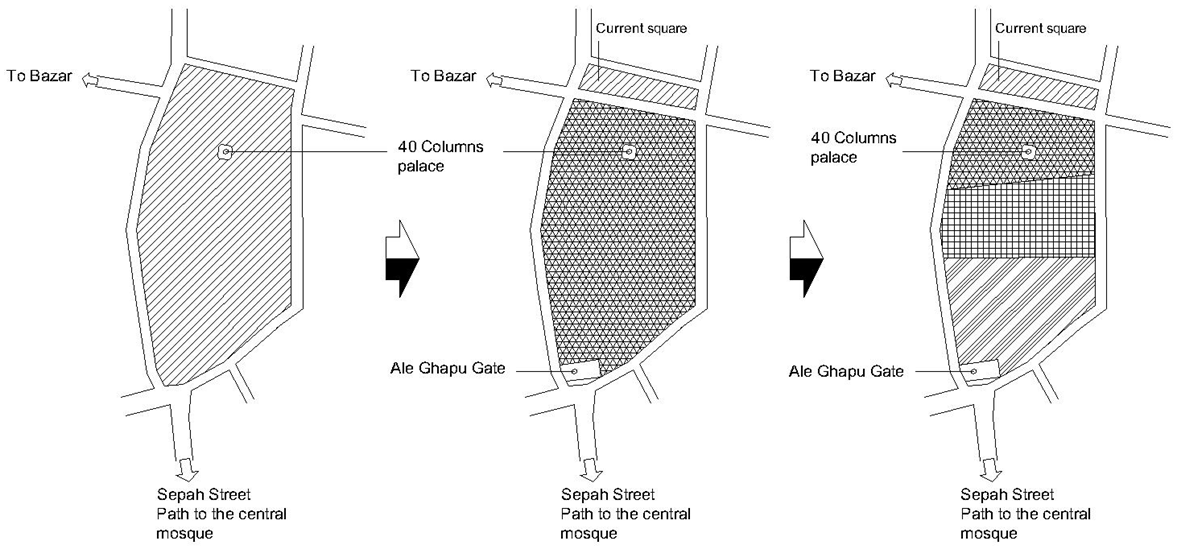

Qazvin’s Sepeh Street is the first designed Iranian street which was built during the Safavid period during Qazvin's capital and was officially registered as the first Iranian street in the national monuments in 2008. Peter Delawala, Italian sailor who spent four years on the Great Shah Abbas board, described this street as follow:"The square is somewhat of a royal palace far and near the market. It is smaller than the big square of Isfahan, but less beautiful than it, and like Isfahan Square it is three times as long as its width, which is probably made for playing polo, because in the sides of the square Stone columns have been installed (www.traffic.qazvin.ir, 2015).The main axis of the physical development of Qazvin city in the Safavid era was the Jami Mosque in the north of the city and the gardens known as Jafar Abad in Sa'adat Abad and Zangi Abad. At the end of the northern area, the street was connected to the royal citadel, located in the garden of Saadat Abad, through the great Ale Ghapu gate. The royal castles and palaces formed a royal city that connected the city through the mosque, the streets and joined the market from the west through the gates and passages (Figure 1). This function structure of squares continued until the late Qajar period (18th Century) with the community of city elders and nobles. The green square was located in the northern part of the garden of Saadat Abad. Before leaving the garden during the Qajar era, the enclosure was empty. In the Qajar era, there was no major change in the government and the popular sections of the city, and the same structure was worn out and in some cases ruined by construction of offices, factories, bridges instead of squares, and streets became the bypass of markets in urban inversion. The other fundamental functional changes Includes:- Changing the nature of the communication network of pedestrians and riders and cars.- Moving the city center from the end of the Government Street (Sepah) to the Grand Hotel and the Brigade of the Current Field and Pahlavi Governorate (40 columns Mansion).- The construction of urban green spaces in the city park of and green square (Establishing recreational centers in the city are the themes of urban expansion in this period) (Mazhab, Sohaeli, 2013). | Figure 1. The whole complex of the Safavid government in the time of Shah Tahmasb Safavi sixteen century (left), The structure of today's Qazvin’s green Square (right) |

The present green square was part of the 40 column garden. From the east to the west and north, the garden was very tall and a small gate connected it to the Rasht (Pahlavi) street, where people and members of the governor came and went from (traffic.qazvin.ir 2015). Abdi Beigi, in various parts of his poems, refers to the commanding idea of this space and the presence of the king's loyalty on the street, in the description of the strong order governing the space and the location of the street between the two royal ports (Al Hashemi, 2012: 68). So it can be concluded that the green square with the present conditions at the time of Shah Tahmasb had no proper structure and only part of it could be used by the public. | Figure 2. Qazvin’s green square in the 19th century (www.khiaraji.blogfa.com, 2015) |

The perch is the only remains of the royal palace since of Shah Tahmasb Safavi (16th centry) in Qazvin, built on the basis of a map of a Turkish architect in two floors, with halls and small rooms on each floor. The first floor wall paintings are a sample of the Qazvin School of Art Painting and is world renown. This building is currently been used as Qazvin’s treasury (museum). The Eight Heaven Building of Isfahan was built with the grace of this work (www.khiaraji.blogfa.com, 2015). Several years ago, instead of the present mansion around 40 columns, there was a vast garden, built in the southwest direction of the great monument called Ivan Nadiery, which, despite its name, determined the perfect style of the Safavid architecture, and was in fact part of the 40 columns mansion (Figure 3). But there are no known remains left of this building today. The collapse of this valuable complex was gradually taking place after the transfer of the capital to Isfahan in 1007 AH (Naima, 2009: 282). | Figure 3. State and private center of the kings and rulers of the Safavid dynasty, 40 columns Qazvin, 2015 |

Today's structure of Qazvin’s Green Square has undergone many changes, such that apart from the parts of the forty columns palace, the surrounding pavilions and the great gate of Ale Qapu, the remaining pieces have been changed. The main reason for this change is the change in the centrality of government to Isfahan, which has left the Center losing many of its values and planning, along with its subsequent advances, and the other factor in the impact of urban transportation, such as cars entered Iran in the late 19th century, resulting in major changes to all urban structures and road routes (Figure 4). Since then the square has been the base line for the south of the city as the traditional part and the north to become the develop and modern aspect of the city. therefore, a cultural gap has been established and the square is considered as the middle ground. | Figure 4. Panorama photo from the current conditions of Qazvin’s Green Square, 2016 |

1.2. Isfahan’s Naghsh Jahan Square

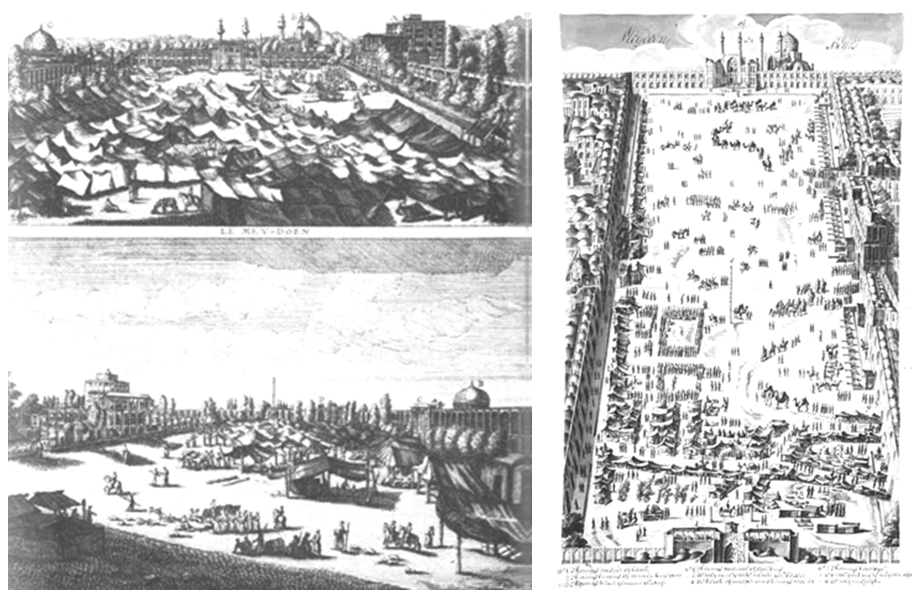

The Safavid architecture is not composed of a combination of buildings, but exclusively composed of closed spaces that rush to the facade and the surface of the building. Multiple motor systems create self-sustaining gravity arrays and are woven into a comprehensive pattern whose complexity can only be compared with the sixteenth-century carpet garden design (Ardalan, Bakhtiari, 2011: 127). The originality of the Iranian city here is totally unified; the city extends to three distinct levels. The first level is located at the height of the flat roofs of the city and covers most of the land; Underneath it is the level of passages and squares, and eventually the turn reaches the level of prominences and heights that splits the general and general ceiling of the city. As a result, urban fabric is just the opposite of the texture of western cities, that is, here are gaps (yards and squares) that create urban islands and not so large buildings (Strilen, 1998: 58 and 62).Eighteen massive mosques built near the city centers have shaped the religious life of the city's squares. Architectural analysis and the role of these mosques were to a large extent represented by the religious organization in the new capital of Shah Abbas Foundation. Naghsh Jahan Square was built in 1602 Ac and the beginning of the construction of the Shaykh Lotfollah Mosque was also in the same year. The Qaisery market was completed in 1617 Ac; the major stages of Qapu's construction were from 1616 to 24 Ac. The last plan of Shah Abbas, which is located south of the square, is the Shah (Imam) mosque (Blake, 2002: 149 & 150). | Figure 5. Naghsh Jahan Square during a game of polo, taken from the oldest movie available of this collection |

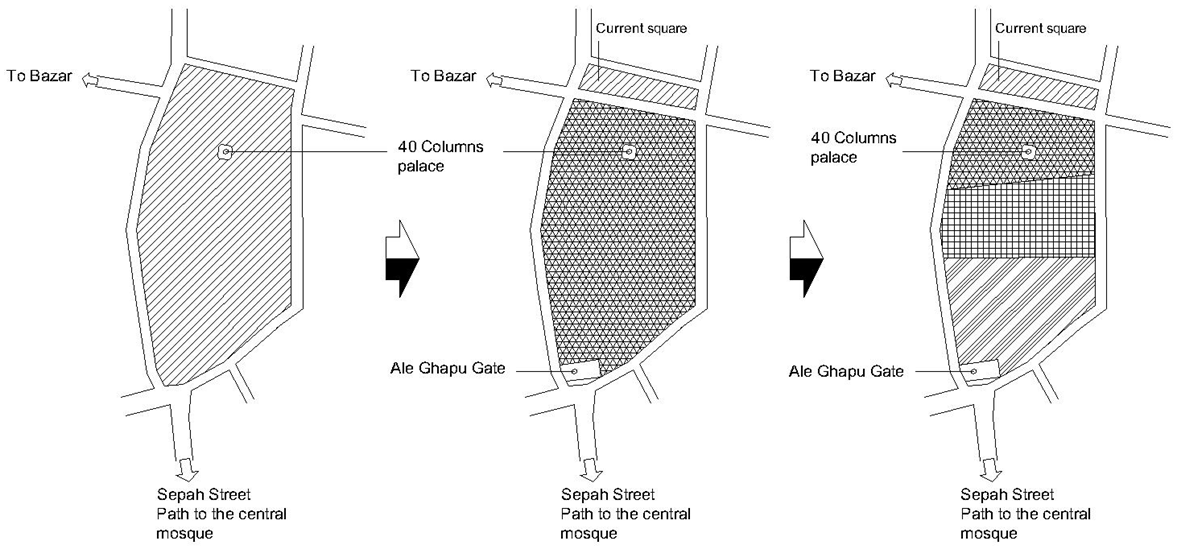

It can be said that the idea of constructing Naghsh Jahan Square and its prominent elements during Shah Abbas’s dynasty was influenced by Qazvin’s green square (Shah Square), and as much it is in the proximity of the old square of Isfahan in the vicinity of the old city mosque (Shahabi Nejad et al., 2014: 48). Naghsh Jahan Square with its extension had two main functions at its time. Firstly, military operation (Fig. 6), which carried out the parades of the military to show the power of the government at the time, and the other was polo game, due to it been considered royal games, and it was also transmitted to Europe (figure 5). | Figure 6. Contemplation of the 18th century European painters of Naghsh Jahan Square (Raadhmadi et al., 2011) |

| Figure 7. Naghsh Jahan Square, 2016 |

In the Qajar period, although the overall structure of the square did not change Naghsh Jahan Square, declined in all its aspects, including the health of the building, urban activities, and economic aspects. The activity of many commercial units were shut down around the square (Figure 8). During the Qajar period, two important elements were neglected in the field, vegetation and water, which reduces the beauty and charm of the square for travelers and other individuals (Shahabi Nejad et al., 2014: 50, 52). | Figure 8. The evolution of Naghsh Jahan Square since the Safavid period tillthe present date |

One of the most significant changes made after the Islamic Revolution is the prohibition of the use of automobiles in Naghsh jahan Square. The law was passed by the mayor of Isfahan in 2014, and according to it, other than Friday (transport of worshipers by bus), no other means to enter the center by vehicle. By implementing this law, many of the structures, texture, form, beauty and morale of this section are preserved.As a current urban aspect of Isfahan is containing a high cultural and economic value. It is one the most visited tourist attractions in Iran and with it a guide line and base development for the city. As such, the majority of the location adjacent and near its’ location is financial or public structures.

1.3. Kerman’s Ganjali Khan's Square

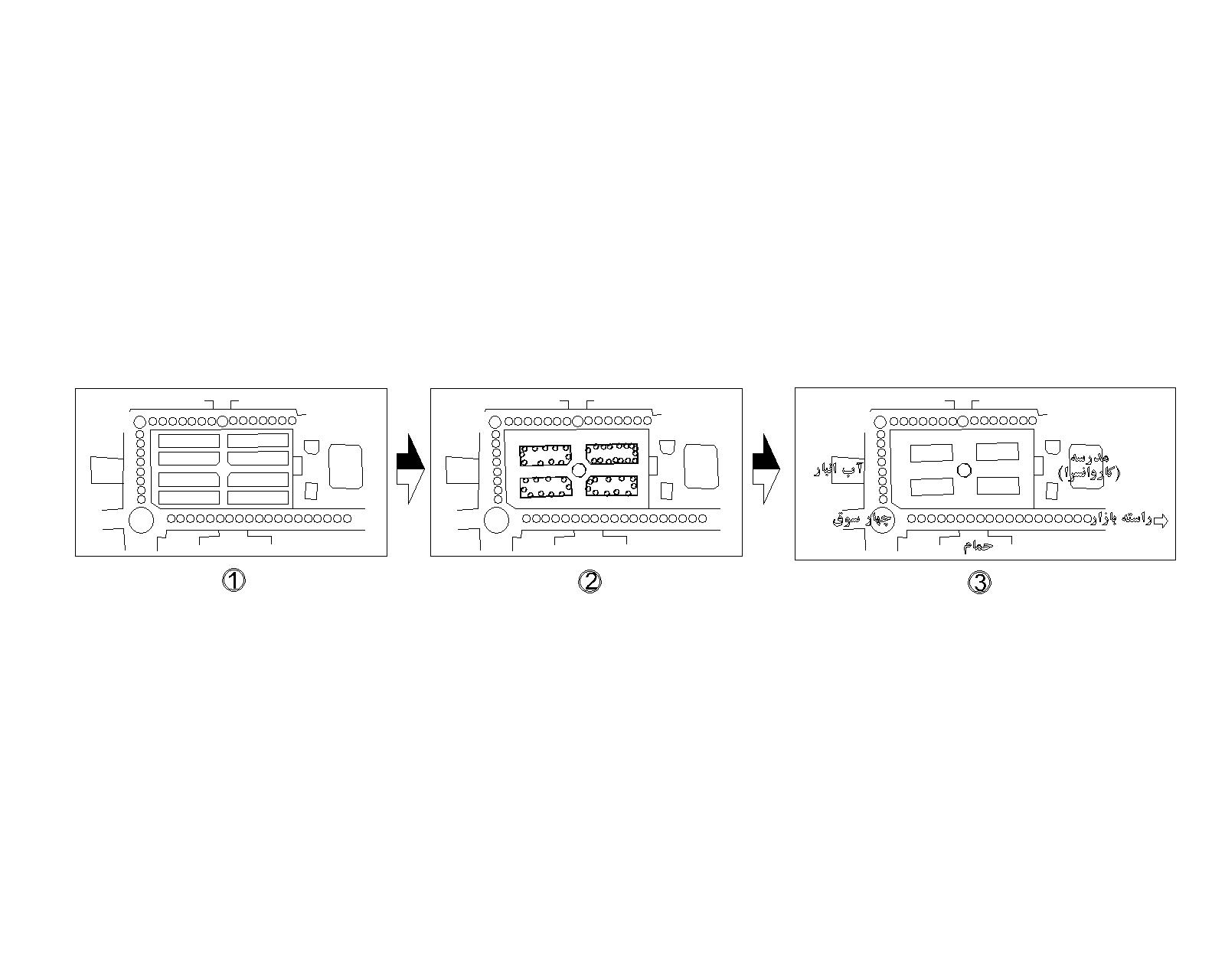

In accent time Kerman was referred to as Kariman Gavashir Karmaniyah or silk towns. Ganjali Khan Square, has an approximate area of 4500 square meters, from three sides it is connected to the market and its eastern boundary to Ganjali Khan. This square was at the time of Ganjali Khan and the subsequent governments that came to Kerman from the Safavid kings, their headquarters and dignitaries, and a place where soldiers and patrols gathered, and they were politically engaged in this area (Motedayen, 2010: 19, 170). | Figure 9. General structure of Ganjali Khan Square before the recent changes, 2006 |

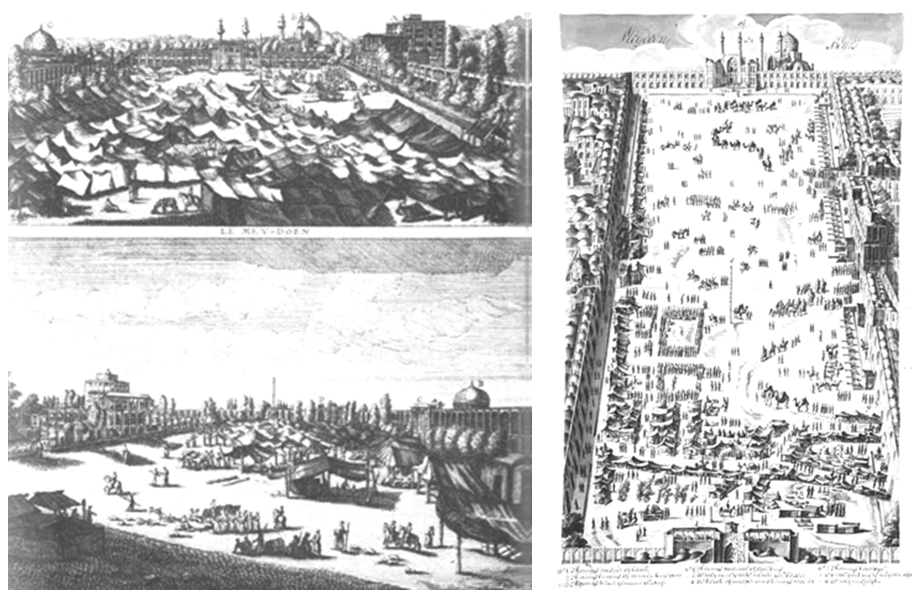

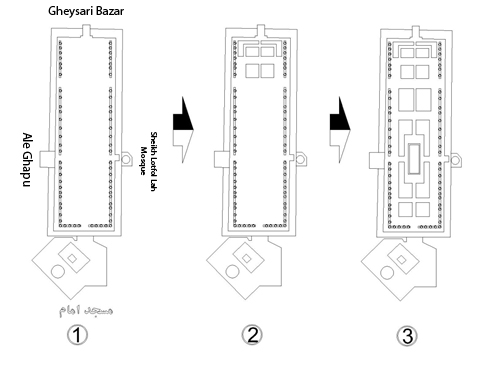

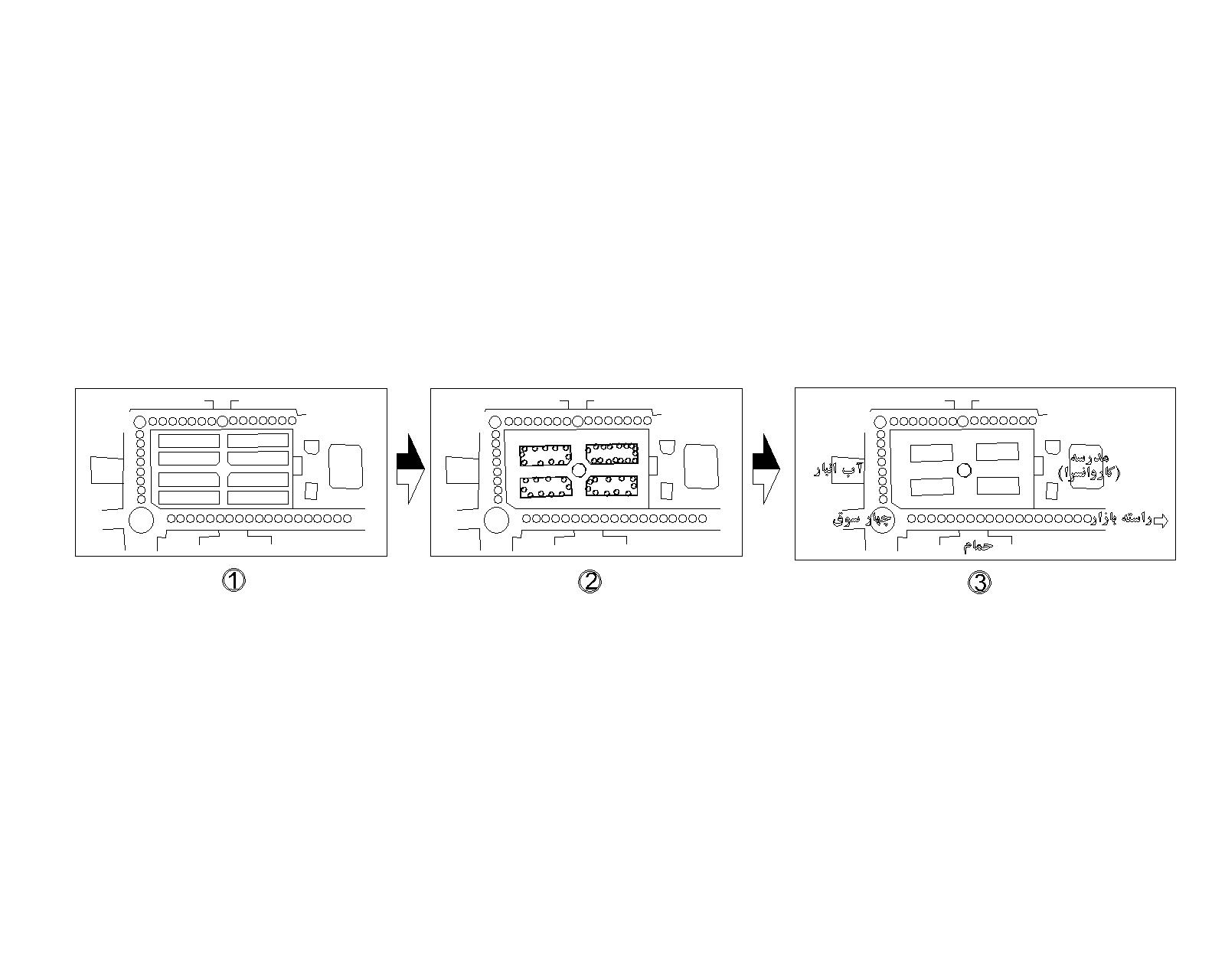

Ganjali Khan, the ruler of the Safavid times in Kerman, has been somewhat diligent in the city's abundance and beauty. It seems that a complaint from the people from him also came to King Abbas that the Shah personally came to Kerman and returned when he realized that Khan's services, such as construction of the buildings, squares, baths and mosques, blessed his oppression and in fact, including writing a letter of complaint to the people that did not approve of him, and allegedly said the sentence:" ... the complaints of the people will end, but the monuments will remain ... "So engage in your work (Bastani Parezi, 2013: 60 & 61).Since the Pahlavi dynasty to the present day, extensive repairs have been carried out in Ganjali Khan Square. First of all, Ganjali Khan bath was generally transformed and renovated as one of the main tourist attraction in Kerman. After that, the governmental house, which was used as a state center until the Qajar period, turned into a museum of coins. The only part that to date has been lacking in its reconstruction is the school (karvansara), which, despite its many years of effort, has not yet made any significant progress. There is no detailed information of the sqaures basic form, but since the Pahlavi era until 2016, The form evolution can be seen in Figure 10, its form was recently changed in terms of function and aesthetics (possibly to change the pseudo-cross field shape). | Figure 10. Ganjali Khan Square current state, 2016 |

| Figure 11. The evolutionary process of Ghanjali Khan Square in the past 150 years |

Unlike the other squares that have become the base line for their cities development, Ganjali Khan Square is located in the old and cultural section of the city and most major and modern development till the last 20 years have acquired on the far west side of the city. And the approximate of the square since the last 300 years has remained an economic cultural setting for Kerman.

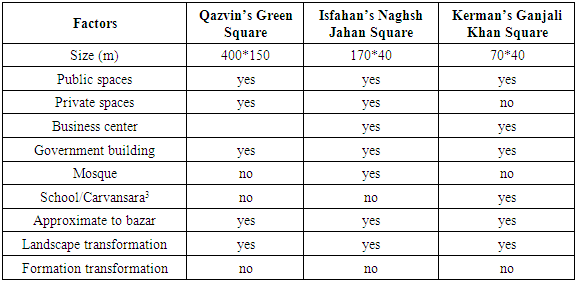

2. Comparing the Structure of Safavid Era Squares

Architecture in Iranian territories in which the climate is hot and arid possesses its own specifications. It is dependent on the climate, religion, worldview and above all culture that has had the greatest impact on its architectural features. Being humanistic and proportional, abstinence from inanity, having structure as aesthetic elements, self-sufficiency, introversion, purity in shapes and volumes, having symmetry and being colorful are some of the origins that can be found in any building of Iranian Islamic architecture (Hosseini, Zand Karimi, 2012: 318). The dominant shape used in Safavid’s squares are rectangular; however, there is a general difference in the type of rectangle used in the three under study squares. The main form of the Qazvin’s Green Square was formed in subsequent periods; its structure with a basic sample in Kerman’s Ganjali Khan has a similarity in many aspects, but Isfahan’s Naghsh Jahan Square has a form that has been drawn out which seems to be out of proportion in terms of aesthetic view possibly due to adjust it according to the need for a polo game, and secondly, because of the wide range of planning that exists for this field, it needs a more structured respond to its uses.Site investigations illustrated that in the traditional Persian architecture, the shapes and the forms have gone beyond their material and familiar meaning and in every direction they acquire a higher quality than their apparent ones. The geometrical shapes of the square, circle, and octagon and so on, have their own value position and are symbols of the artist's religious beliefs; but beyond the geometrical shape and material volumes and sizes, even elements like light have their outstanding position in the religious art (Taghizadeh, 2012: 5&6). The other considerate versatility in terms of these squares is their private or public aspects. If the Safavid capital was not moved from Qazvin to Isfahan in the 16th century, the entire Green Square would be a private structure for the monarchs. Naghsh Jahan Square, due to its wide range, has a private and public mix. Therefore, the Ale Qapu and the Sheikh Lotfollah mosque were only available to the Shah, and even had their own underground communications route. Meanwhile, Ganjali Khan Square was a public center, even the Mint (Coin Museum of Today) which was the state center of the time.One of the major contradictions in these three fields is the difference in the extent of their functions; so much that the Green Square was the first square structure during the Safavid era, and in later instances this subject was expanded to a certain extent in Naghsh Jahan Square, which, despite its smaller proportions, has the highest functional variation then the other two.

3. Conclusions

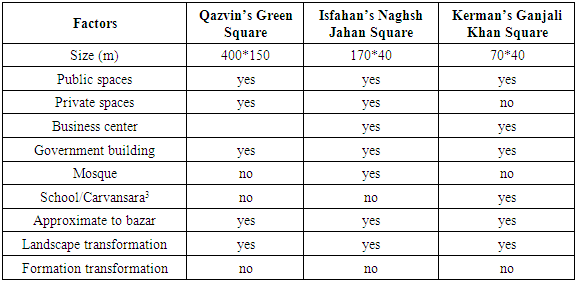

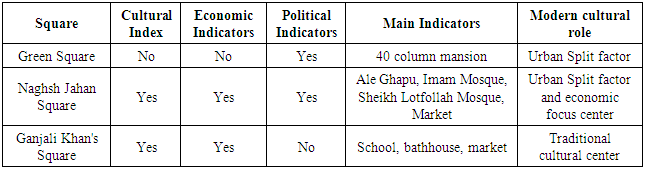

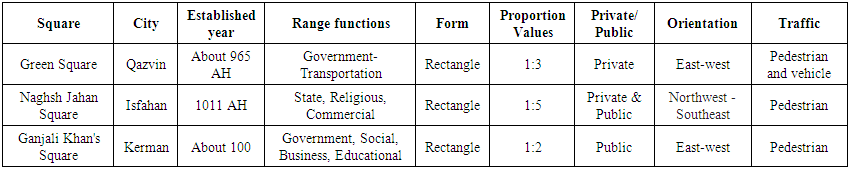

During the Safavid period squares formed one of the main urban structures, and this effect continues to this day. The three squares analyzed in this study, despite the time prediction, have a variety of differences from each other. The performed analyzes have shown that the main similarity of the samples is their rectangular shape structure (Table 1). From a commercial, social, and applied point of view, each square is different from in at least one of these aspect with the others. The main factor influencing this issue is the political factor at that time. From the reviews, we find that the difference between the Green Square and the other two fields is in its pure state and governmental structure that the social and commercial elements have been added to this field have occurred in subsequent periods; The inverse of it is the Ganjali Khan Square, which at the same time began to build its social structure and later became the main point of creativity in the center. In terms of the extent of the squares, the role of Naghsh Jahan Square is the largest and most complete of the three, and the reason for this, as we said, goes back to the political domain of that time. Finally, with many of the differences in these fields, all of them have a common goal, which is to create a centralized urban structure and integrate it. | Table 1. Primal Indicators |

Table 3 summarizes the social influences such as culture, economics and politics to evaluate the regional approaches of each field, thus culture here includes the elements of the public gathering.Table 2. Comparative structure of squares forming factors

|

| |

|

Table 3. Social Valuation Indices of the Safavid Squares

|

| |

|

Table 3 concludes that because of the capital structure in the Green Sqaure and Naghsh Jahan Square, the political factor is very high, contrary to Ganjali Khan's Square, which has a more social and cultural structural valuable especially because it is adjacent to the market. Among the three examples examined, Naghsh Jahan Square has all three characteristics, in which the attention of government, community culture and economy of the city’s inhabitants is at a higher level with a more religious and state value.Overall each of these centers, even in the current modern urban structure, is considered not only a bases for traditional Iranian culture but also a tourist and economic center for the city. Therefore, the original purpose of these square in some ways is still intact and as such different cultural and civil aspects revolve around each one.

Notes

1. Safavid dynasty is considered one of the most significant era of Iran which established in the beginning of the 16th century for more than 200 years. One of the most known critical aspects of this era was the inception of foreign economy and cultural. 2. Based on Pernia’s original theory Iranian Traditional Architecture is conducted in to four primal category styles: Khorasgani, Azari, Razi, and Isfahani.3. Carvansaris are the equivalent of traditional European Inns with a traditional central courtyard architecture.

References

| [1] | Douzdouzani, Y. Etessam, I, Naghizadeh, M. (2014). An Investigation to Physical Aspects of Middle Area in Squares as a Useful Indicator for Designing Community-Oriented Urban Plazas. International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development. 4(3). |

| [2] | Ardalan, N. Bakhtiari, L. (2011). Sense of unity. Architectural science Publication. Tehran. |

| [3] | Strilen, H. (1998). Isfahan Image of paradise. Publishing and research of Farzan day. Tehran. |

| [4] | Al Hashemi, A. (2012). Qazvin Street: Reviewing Qazvin Street Based on Abdi Bey's Poetry and Other Available Books. The scientific journal of Nazar Research Center, for Art, Architecture & Urbanism. 22. 65-74. |

| [5] | Bastani Parezi, M. E. (2013). Kerman history. Science publishing. Tehran. |

| [6] | Blake, Stephen. (2002). half of the world. Translated by Mohammad Ahmadinejad. Soil Publishing House, Tehran. |

| [7] | Fardpour, T. (2012). Analysis of Iranian Traditional Architecture through the Lens of Kenneth Frampton’s “Critical Regionalism”. American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences. 6(2). 205-210. |

| [8] | Hosseini, B. Zand Karimi, A. (2012). A Breif Survey on the Principles of Iranian Islamic Architecture. Archi-Cultural Translations through the Silk Road, 2nd International Conference, Mukogawa Women’s Univ., Nishinomiya, Japan, July 14-16. |

| [9] | Pirnia, Mohammad Karim. (2004). Stylistics of Iranian Architecture. Soroush Danesh Publications, Tehran. |

| [10] | Pourjafar et al. (2009). Philosophical Approach in Studying Iranian Architecture. Intl. J. Humanities. 16(2). 87-114. |

| [11] | Raadhmadi et al. (2011). Introducing and criticizing several recent historical image documents on Naghsh Jahan Sqaure. The scientific journal of Nazar Research Center, for Art, Architecture & Urbanism. 17. 18-3. |

| [12] | Rahnamayi et al. (2007). The structural and functional evolution of the neighborhood in the cities of Iran. Scientific and Research Journal of the Iranian Society of Geography. 5(12 & 13). |

| [13] | Taghizadeh, K. (2012). Islamic Architecture in Iran, A Case Study on Evolutionary of Minarets of Isfahan. Architecture Research. 2(2). 1-6. |

| [14] | Motedayen, K. M. (2010). Kerman detailed history. Goli Publication, Tehran. |

| [15] | Mazhab, B. Sohaeli, J. (2013). The green square of Qazvin over time. National Conference on Urbanism and Architecture (Islamic Azad University of Qazvin). |

| [16] | Shahabi Nejad et al. (2014). Historical Formation and Metamorphosis of Isfahan’s Naghsh Jahan. Restoration of Cultural Heritage Journal. 2(3). |

| [17] | Naima, G. (2009). Iranian gardens. Payam Publication, Tehran. |

| [18] | www.khiaraji.blogfa.com, 2015. |

| [19] | www.traffic.qazvin.ir, 2015. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML