-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2017; 7(4): 109-122

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20170704.01

The Role of Public Art and Culture in New Urban Environments: The Case of Katara Cultural Village in Qatar

Maryam Al Suwaidi1, Raffaello Furlan2

1Candidate in the Master Program in Urban Planning and Design (MUPD) at Qatar University, State of Qatar

2College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning (DAUP), Qatar University, State of Qatar

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan, College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning (DAUP), Qatar University, State of Qatar.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In recent years, public art has been featured as a trend in urban environments in GCC. During its period of development, the State of Qatar worked on large megaprojects designed to attract global investments and tourists. Also, the current process of globalization has greatly contributed to increasing competition between cities and promoting the development of public art within new urban developments. This research study discusses the role of public art in influencing urban environments in Qatar, namely within Katara Cultural Village. The study explores the extent to which such an approach can raise local communities’ environmental awareness as an indirect input to the process of upgrading the desires of those living in these areas and of international tourists. In addition, it reviews the experiences of different types of catalysts for regeneration, such as art and culture, that can enhance the built environment’s recognition, value, and economic growth. A qualitative evaluation is employed for this research study, which leverages subjective methods such as interviews and observations to collect substantive and relevant data while examining the interaction of connectivity, attraction, and development as they relate to economics and other multifaceted aspects of development. The findings reveal the main advantages and disadvantages of introducing public art to an urban space, namely in regard to acceptance, culture, and social behavior. In addition, the study helps identify new ways to use public art to enhance public interactions and participation in new urban environments.

Keywords: Cultural Planning, Culture, Cultural Districts, Katara Cultural Village, Gentrification, Tourism

Cite this paper: Maryam Al Suwaidi, Raffaello Furlan, The Role of Public Art and Culture in New Urban Environments: The Case of Katara Cultural Village in Qatar, Architecture Research, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 109-122. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20170704.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Qatar continues to transform its art and culture to embrace the forces of urbanization that began to be witnessed in the country from the second half of the 20th century onward. Urbanization gave rise to an increase in oil production and lucrative oil export contacts that made Doha, the capital of Qatar and one of the oldest cities in the GCC, grow both economically and demographically. This growth puts Doha in a strategic position to attract artists from across the world to witness its rich cultural traditions, practices, and artifacts and to relate them to those from other countries. Development initiatives, however, are bound to encounter obstacles; in Qatar’s case, there are obstacles to maintaining its cultural identity in an era characterized by rapid development caused by urbanization (Furlan & Faggion, 2015b; Furlan, Rajan, & AlNuaimi, 2016). [2-9].Every development phase encounters obstacles, and in Qatar’s case, the difficulty lies in moving toward modernity while preserving the nation’s cultural identity, which Qataris highly value [10, 11]. According to the Qatar National Vision 2030 [12]:Qatar’s very rapid economic and population growth have created intense strains between the old and new in almost every aspect of life. Modern work patterns and pressures of competitiveness sometimes clash with traditional relationships based on trust and personal ties. Moreover, the greater freedoms and wider choices that accompany economic and social progress pose a challenge to deep-rooted social values highly cherished by society. Yet it is possible to combine modern life with values and culture. Other societies have successfully molded modernization around local culture and traditions. Qatar’s National Vision responds to this challenge and seeks to connect and balance the old and the new.During this time, Qatar worked on large megaprojects designed to attract global investments and tourists [4]. Undoubtedly, the current process of globalization is heightening competition between cities and affecting the very establishment of a relationship between public art and urban development whereby public art is valued or rejected as a tool for increasing the individuality, uniqueness, and attractiveness of cities and consequently providing work for the local economic base while safeguarding and preserving cultural identity for future generations (see figures 1, 2, and 3) [9, 13-15]. In addition, public art provides a platform for local and international artists to examine the ingenuity of contemporary art.

| Figure 1. Lamp Bear by Urs Fischer, Hamad International Airport |

| Figure 2. Smoke by Tony Smith |

| Figure 3. East-West/West-East by Richard Serra, Zekreet Dessert |

2. Literature Review

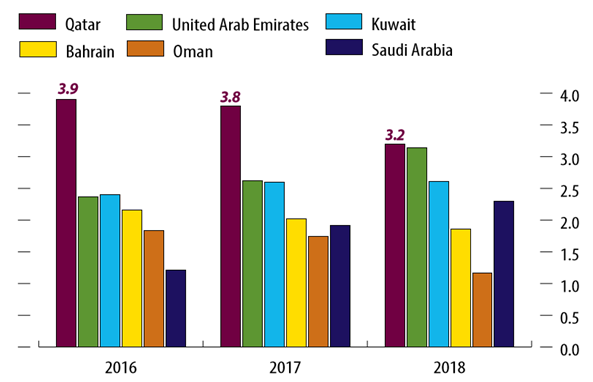

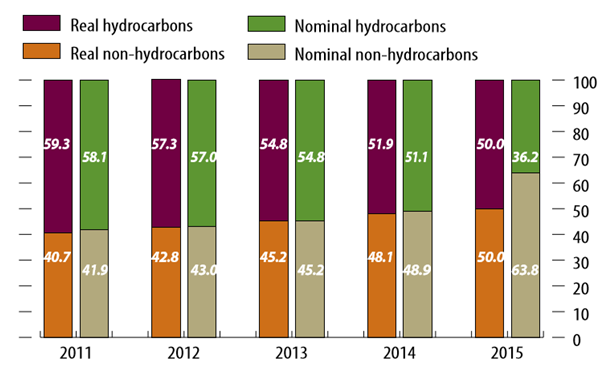

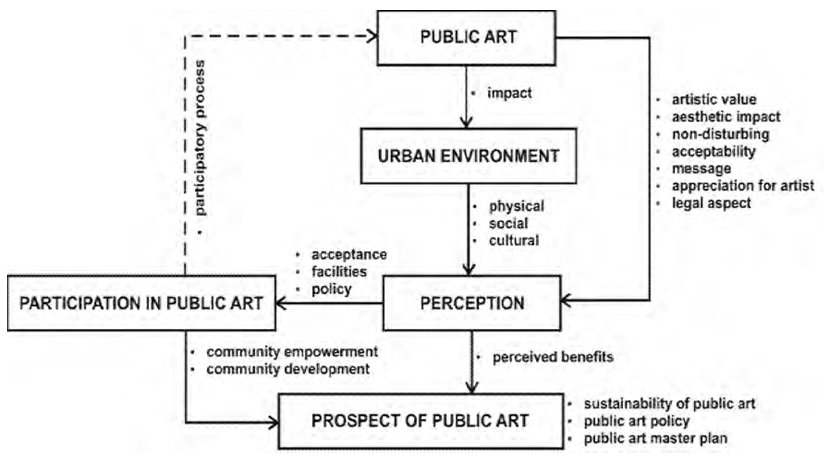

- Public art, according to Public Art Southwest of the United Kingdom, is defined as follows:The term public art refers to artists and craftspeople working within the built, natural, urban or rural environment. It aims to integrate artists’ and crafts people’s skills, vision and creative abilities into the whole process of creating new spaces and regenerating old ones, in order to imbue the development with a unique quality and to enliven and animate the space by creating a visually stimulating environment [26].Public art may also be defined as site-specific art presented in a public area. Such art has experienced something of a rebirth in recent decades, aided by increases in the number of public- and private-sector commissions, expansions in arts policy, and artists’ participation in many areas as part of broader urban design and regeneration initiatives [27, 28].Such art pieces can come in many different forms, each of which represents social, cultural, or universal values. They may also draw on heritage, highlighting the most important aspects of a region or nation. However, it is worth noting that such a relationship between art and cities is not new. History regales us with tales of city authorities who supported art to give their city a competitive advantage—whether in reputation, prestige, or even just attractiveness—over similar cities [29].Initially, public art referred to urban sculpture, but after the development of urban construction, the range of public art forms has expanded to include all things that can be made artistic in people’s public living spaces. Indeed, the existence of urban sculpture, in addition to murals, plays a significant role in developing a given community, and the city embraces traditional buildings and also seeks to construct buildings that capture the cultural and artistic aspects of that community [30-35].There has been concern that the main purpose of public art is simply to renovate old concepts and produce works that affirm people’s belief in the already constituted culture and customs. However, the reason public art is becoming increasingly mainstream in the view of artists is because it is actually a way to protest cultural norms or critique urban development. It seeks to pose questions to the viewers that elevate their ambitions for the society. The challenge for public art is to be more than a critique from within the development and design team that has come to be employed by many artists. The goal of the artist is to assume a role more akin to that of community activist than that of architect or planner. This goal is depicted in the well-known example of the ‘Culture in Action’ exhibition curated for Sculpture Chicago by Mary Jane Jacob [36].Here, the coalitions formed are not with other design professionals seated around a conference table but with members of the lay community who might have a completely different sense of priorities for economic and physical development. The result might be process- or event-oriented rather than oriented toward an object, structure, and surface. The goal might be to expose the underlying political and economic ambitions of a development project rather than to assume any effect on its aesthetic quality [37].According to Thomas, certain universal needs are perceived in the urban environment. These universal needs—or, in Thomas’s words, “universal invariants”—can be used as references to qualitative aspects and physical planning by urban designers and planners as they seek to develop more productive urban environments [38]. This point raises a further question: What is the value of public art in an urban space?The Prospect of Public Art in the Context of Urban EnvironmentsSustainable development, according to several scholars, plays an important role in deciding the social features of urban environments [39-44]. Urban settlements and buildings originate in social interactions [45]. Public art as a tool of development strategy has a significant role to play in advancing different aspects of urban planning and design. Architecture and sculpture are important categories of urban public art. In particular, sculptures (and murals) play an important role: In many public spaces, sculpture is the focal point for construction and a bright spot for visual images, and architecture has multiple equally-important identities in public art [46]. According to Chunhua, “It is important for the aesthetic field, in the process of an aesthetic experience, [that] people accept aesthetic information, ideological and spiritual values transferred by works of art.”In light of this consumption-related concept, in which public art promotes city beautification that itself supports marketing strategies designed to attract mobile international capital and specialized personnel, it is important to stress that this relationship between art and cities is not new. According to Canter’s metaphor for place [47], all successful urban places comprise three elements: activity, whether in financial, cultural, or social form; the nature of the relationship between buildings and spaces; and meaning, which arises from a sense of place and historical and cultural context.Economic AdvantageDoha might be viewed as the most progressive city in the Middle East for following the concept of economy as a calculated base for its 2030 vision [25], in which it goes beyond the typical image of a Gulf city possessed of seemingly endless assets of oil and gas [48, 49]. By expanding its economy to attract visitors and encourage tourism, the city of Doha promotes itself as a cultural center and a place to host international sporting events [50]. Farlance, a city featuring extensive public artwork, is a highly cultured city—a status that brings it economic advantages by helping it attract new industries because it serves as a place where specialist employees and executives would be happy to relocate (see figures 4-5) [49, 51].

| Figure 4. Real GDP growth forecasts, GCC (year-over-year change, %) |

| Figure 5. Hydrocarbons and non-hydrocarbons, share in real and nominal GDP (%) |

| Figure 6. Developing a sense of community |

| Figure 7. Sheraton Hotel (left) and Teapot Sculpture (right), Corniche |

| Figure 8. Conceptual model |

3. Methodology

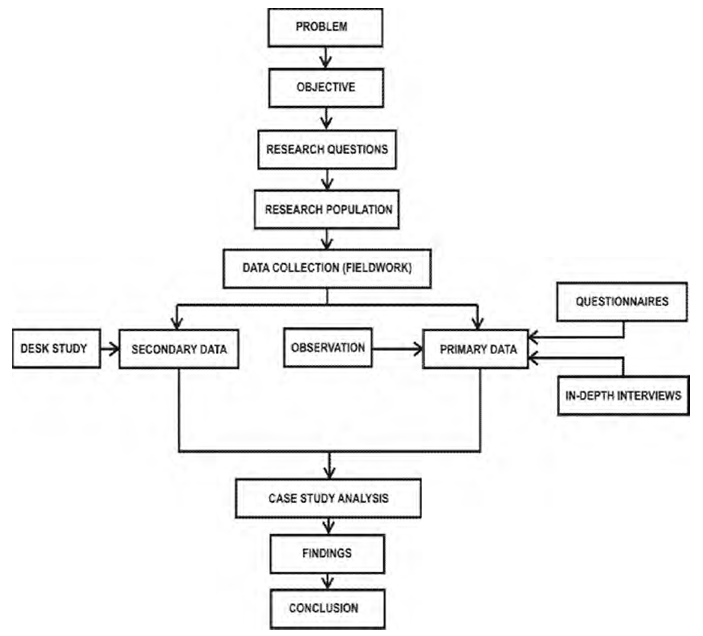

- This research study focuses on why and how art and culture affect a specific instance of urban development. Qualitative evaluation is applied to this study by leveraging subjective strategies, including interviews and observations, to collect major and relevant data [64-66]. The overall process includes three key steps: interviews, observation, and plan application. The overall process is structured to take place over a four-month-long period.A number of accessible approaches contribute to data gathering. In this research study, the authors will use two mainstream methods for conducting research: primary and secondary data collection. According to Creswell [67], when primary and secondary data are used, the secondary data is usually employed to clarify the primary data. According to Ghauri and Gronhaug [68], secondary data helps readers develop a better understanding of the research topic.This analysis uses the purposive technique to pick out source persons, a group of people representing all stakeholders involved in the subject of the study, to interview; in this case, they are key members of the artist group, local authorities, key members of society, and specialists in related disciplines. The purposive random sampling technique is also used to solicit responses from citizens about their general perceptions of public art on surveys distributed to users of Katara Cultural Village; these are random individuals whose nationalities and behaviors correspond to the location and its intended uses.Observation and mapping are additional tools used to understand the dynamics of people, their interactions with the urban environment, and the type of art used; this alternative approach to data collection views people as objects by recording their behavior periodically, and valuable information is obtained when their behavior is systematically recorded in this way [69]. Unplanned observations may result in inadequate findings that do not extend beyond surface appearances. Systematic observation of behavior, in contrast, takes into consideration four elements: people, activities, setting or space, and timing [70-73].The research observations will be conducted within the administrative boundary of Katara Cultural Village. Open-boulevard murals (murals along urban streets) are observed in the areas surrounding different public works of art [27]. The study will focus on the following issues:Ÿ Understanding public art and how it helps change the urban environment;Ÿ How citizens perceive public art projects and their contribution to the environment;Ÿ Citizen participation in public art;Ÿ And the prospects for public art in Katara.Technical and artistic aspects of the art will be discussed to a very limited degree because these intrinsic aspects of art are not the focus of this research.

| Figure 9. Katara Cultural Village location |

| Figure 10. Gandhi’s Three Monkeys by Subodh, Katara Cultural Village |

| Figure 11. Murals as public artwork, Katara Cultural Village |

| Figure 12. Research design [1] |

4. Findings

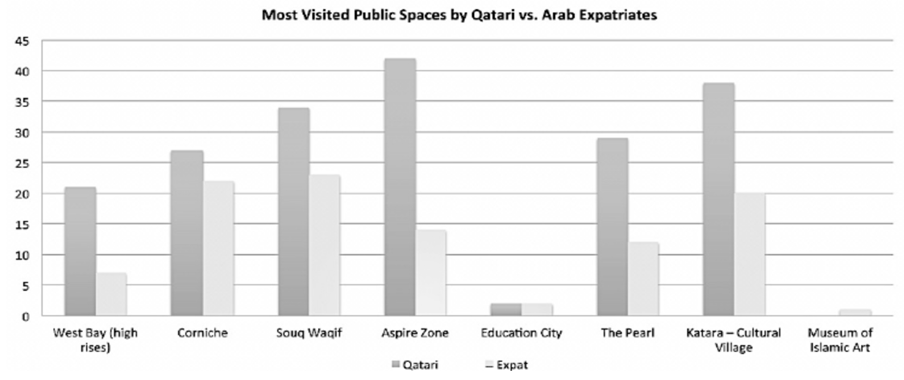

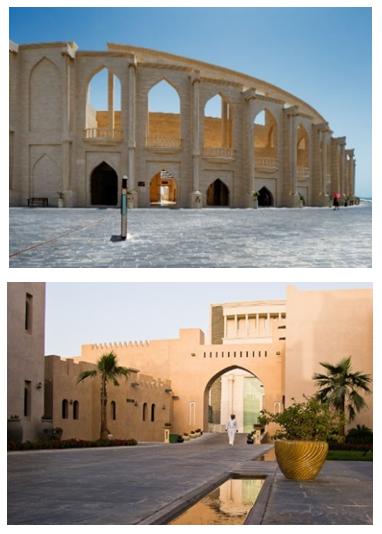

- Katara Cultural Village is a tourism development project located in Doha, near Doha’s West Bay. The village was opened in October 2010 featuring a theater, an amphitheater, libraries, art galleries, a heritage center, museums, and academic facilities—all of these marking the first stage of completion. Surrounding these buildings are retail outlets, coffee shops, museum facilities, and market areas—all designed to embody the historic theme of the site, which also underlies the concept of the village [18, 74].Several Qatari organizations, including the Societies of Qatar Fine Art, the Visual Art Centre, photographic and theater collectives, and the Qatar Music Academy, have their offices in Katara. Thus, this cultural village has developed into a major tourist terminus in Doha as visitors seek out art and artistic performances there. Indeed, average daily visitor counts exceed 20,000, a figure that grows to 180,000 during events and festivals. According to researchers, most visitors to Katara Cultural Village rate it their second most visited urban space after the Aspire Zone, even though Souq Waqif and the Corniche seaside area are conveniently located at the center of the city, where most of the people live [21, 70, 75].This space involves various users, children among them. The users represent different socio-economic divisions and cultural backgrounds and include native residents. The space is designed to accommodate multiple users, including those interested in walking, sitting, relaxing, beach viewing, partaking in and viewing beach sports, eating, and, most importantly, learning about culture and arts through art exhibitions.Observation Various types of public art can be found in Katara, and each significantly affects people’s interactions. Katara features various contemporary art pieces alongside its traditional Arab architecture. The juxtaposition of contemporary art and imitation of cultural images makes the landscape unique and attractive to tourists. Katara Art Center (KAC) is an independently run platform that was founded by Tariq Al Jaidah in 2012. KAC is dedicated to contemporary art and transdisciplinary creative endeavors, projects, and practices. It acts as a center for developing art and cultural communities that will solve the need for a serious proletarian and multidisciplinary framework in Doha for addressing socially relevant issues, and it will display both historical and contemporary art.Public monuments arise from the desire to openly celebrate individuals or important events. They can be statues or landscapes, and their identification is largely undisputed. These works are part of the official historical record and heritage of public places. In Katara, such monuments include the aviary towers, or the Pigeon Towers. Although only recently built, the towers are significant in Qatari culture and will remain so because of their historical essence and because they help develop a sense of cultural identity.A piece of artwork depends as much on its landscape as on its material, because an art installation must be an integral part of its physical context. As described by Serra, a piece of artwork can distinguish between east and west and provide humans a way of measuring their relation to nature [76]. Like feature events in public places, works of art as feature objects may be integrated or simply inserted into public spaces. Moreover, they may be intimate artistic expressions or publicly accessible statements. Perhaps their meaning most frequently arises in the context of their references to viewers’ backgrounds. Thus, the public space becomes an outdoor gallery or theater. Consider, for example, Gandhi’s Three Monkeys or the Force of Nature, a celebrated focal point for tourists because it originates from a well-known international artist and relates to both the people and the area that constitute its environment.

| Figure 13. Public spaces most visited by Qatari vs. Arab expatriate respondents |

| Figure 14. Facilities in Katara |

| Figure 15. Pigeon Towers in Katara Cultural Village, Doha, Qatar |

| Figure 16. Mosque in Katara Cultural Village, Doha, Qatar |

| Figure 17. Gandhi’s Three Monkeys by Subodh |

| Figure 18. Qatar Wind Statue, Katara Cultural Village |

| Figure 19–20. The Katara Amphitheater, exterior |

| Figure 21. West Bay Lagoon, view from Katara beach |

| Figure 22. The Esplanade (A) and the Amphitheatre (B) |

| Figure 23 |

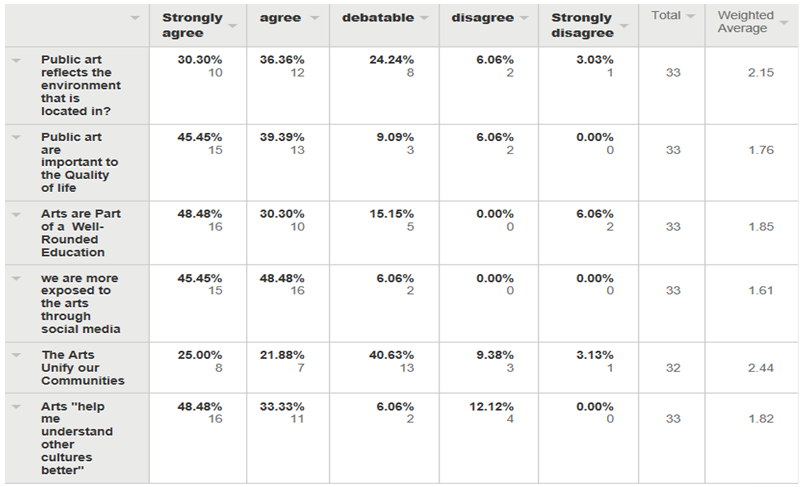

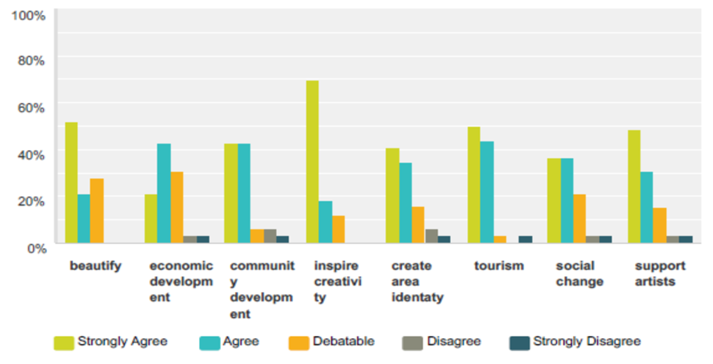

| Figure 24. Survey: What is the role of culture and public art? |

5. Conclusions and Discussion

- Because public art is both unique and visually distinctive, it can take on a symbolic role in establishing a city’s identifiability and legibility, especially when it is designed and created in ways that are consistent with its surrounding area and site. It can also improve a city’s energy while intensifying the place attachment and sense of security that originate from an understanding of familiar elements, and it can intensify social interactions by establishing a connection with citizens and ensconcing the place in citizens’ awareness. The conclusions of this research are as follows. (A) The effect of public art on the urban environment in QatarBased on citizens’ descriptions of their perceptions of public art and its impact on the urban environment in Doha City, specifically Katara, public art has positive physical, social, and cultural impacts on the urban environment and helps determine the livability and sustainability of the city. However, there are also a number of disadvantages related to the application of public art. Most of these fall under ethical considerations; because of ethics and norms, not many works of public art were accepted by society, and in some cases, on the downlow perspective, disagreements arose more than once between societies because of public art. As a result, different social groups formed in society. However, this is a different topic that can be covered in further research.(B) Reflection on the literatureAccording to the reviewed literature, public art is much more than art works placed in a public area to enhance the environment, which is what it is understood to be by many users; instead, it is a tool that participates in urban development and addresses urban issues. For example, the mural located at the entrance of Katara became a current form of public art in Qatar because it is relatively accessible to the people and gives visitors the feeling that they are helping beautify the area, perhaps leading them to contribute to the city’s economic development.(C) Participation in public artParticipation has been considered valuable in development theories because it is an important part of community development and is considered a key element of enablement. However, the decision to participate in environment-related activities such as public art usually depends on how the citizens perceive the art itself and how they perceive the effect of the art on their environment. (D) The prospects for public art in the context of the urban environmentBased on the literature review, public art is believed to bring advantages to the city, particularly for urban development and regeneration. Arts and cultural activity can increase attention on and foot traffic to a location, which attracts foreign and domestic visitors and increases the amount of time and money they spend in the location or the country; as a result, they generally contribute to the area’s development. Public art and related streetscape facilities, such as artist-designed lighting and built areas, are means to attract pedestrians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Maryam AlSuwaidi is pursuing a Master’s Degree in Urban Planning and Design at Qatar University. Raffaello Furlan is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning (DAUP) at Qatar University. This research study was developed as an assignment for the core course Research and Statistical Analysis in Planning (MUPD601, Spring 2017), taught at Qatar University, College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning (DAUP) by Dr. Raffaello Furlan for the Master in Urban Planning and Design Program (MUPD).The authors would like to thank Qatar University for creating an environment that encourages scientific research. Also, the authors would like to express their gratitude to the leading planners and architects from the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME) and Ashghal, the Public Works Authority, for their collaboration, participation in the meetings, handling of visual data and cardinal documents relevant to the research aims, and discussion of the conclusive results of this investigation. In addition, the authors would like to thank the interviewees, Khalid Albeh, Khalifa Alobaidly, Faraj Daham, and Ibrahim Jaidah, for their valuable support throughout this research study. Finally, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which contributed to the improvement of this paper. The authors are solely responsible for the statements made herein.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML