-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2016; 6(6): 154-159

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20160606.03

Sports Arena Development: Scalability Impact on Urban Fabric Integration

Amna Aljehani, Salim Ferwati

Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Correspondence to: Amna Aljehani, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper examines the evolution of arenas and its integration in the urban fabric. Arenas have always been an important building type that has been used since ancient times. The integration of arenas into the urban fabric has become a recent issue with the increase interest for hosting Mega Sporting Events. Mega Sporting Events usually require large structures that sometime are poorly integrated with its surroundings. The focus of this study is to examine the history of sports arenas and its integration into the urban fabric with focus on stadium scalability. In this study, the method used to examine arena development and integration is based on a historical qualitative method to examine the timeline of arena development and impact factors, in addition to the comparison of two case studies: Khalifa International Stadium and Qatar Foundation Stadium. The paper concludes that stadium scalability is impacted by urban form factors such as land uses, density, accessibility and connectivity. These factors impact the decision to scale down or up a stadium for better urban integrations. It also proposes further research questions that can base this study as a critical background study of arena development.

Keywords: Sport Arenas, Stadiums Urban Fabric, Scalability

Cite this paper: Amna Aljehani, Salim Ferwati, Sports Arena Development: Scalability Impact on Urban Fabric Integration, Architecture Research, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 154-159. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20160606.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Stadium has been always a significant building type in the urban fabric (Sheard, 2005). The evolution of arenas into the modern stadium created some challenges and opportunities for urban integration. It is important to study the development of arenas throughout history to detect the factors that impacted its development, and to create critical background study for future development. The aim of this paper is to examine the history of sports arenas and its integration into the urban fabric based on stadium scalability.The integration of arenas became recently relative with the increasing interest for hosting Mega Sporting Events. Mega Sporting Events such as the Olympics and the World Cup requires stadiums and facilities that sometime exceeds the needs of the hosting city. This has led scholars from different fields to study this issue. Most of the literature came from architecture, engineering, planning, economics, political, and social journals. The literature played an important role in formulating the research question and design. It is important to note that there are not many differences between the definition of an Arena and a Stadium. According to Oxford dictionary:- Arena: “A level area surrounded by seating, in which sports, entertainments, and other public events are held”.- Stadium: “An athletic or sports ground with tiers of seats for spectators.”It is also important to note that both the arena and the stadium are used today; however, arenas are usually smaller and enclosed while Stadiums have larger capacity with a more complex structure.This paper aims in tackling the issue of integrating modern stadiums into the urban fabric. In one hand, its study the evolution of arenas as a building type. on the other hand, it examines the impact of stadium scalability on urban fabric integration. The significance of this study lay in creating a solid critical background for future research on stadium development and urban integration, and it will raise questions of adaptability and reuse for further research.

2. Literature Review

- Stadiums, or arena are one of the largest spaces or buildings that impacted the urban built-from of cities from ancient to modern time. To investigate the evolution of arena's integration into the urban fabric, one must first explore the development of arenas in history. Stadia were apparent structure through different historical period. According to (Sheard, 2005 & King, 2010) the development of stadia can be seen in three periods: 1) Ancient Stadia, the Greeks and Romans period, 2) the modern stadia, the development of the European stadium, and finally 3) the Post-modern stadia, the development of stadia as an urban regeneration catalyst. According to Karatzmuller (2010) the origin of the stadiums goes back to ancient Greece and the Roman period, the Greek word “Stadion” meant a 600 feet area; the roman developed the Stadion further that was finally developed as a building type. Originally, the Greek stadia was an area of 600 feet that is surrounded by three slobs for the audience, hill sides were considered good locations. While the Greeks used the stadia for sports and celebration activities, the stadia were further developed after the Roman conquest.The use of concrete helped in creating a multi-story building that is more closed and semi-circle, which provided more control over the audience (See Figure 1). In both times, the stadia were a political building type that aimed in showing power and control. The stadia were used for sports activities, celebrations, or even public announcements. It is also important to note that arenas where important node that is integrated within the city (Karatzmuller, 2010).

| Figure 1. First U-shaped sunken stadium at Athens first built in 331 BC. Source: Geraint, J., Sheaard, R., & Vickery, B. (2007). Stadia: A Design and Development Guide |

| Figure 2. Research Design |

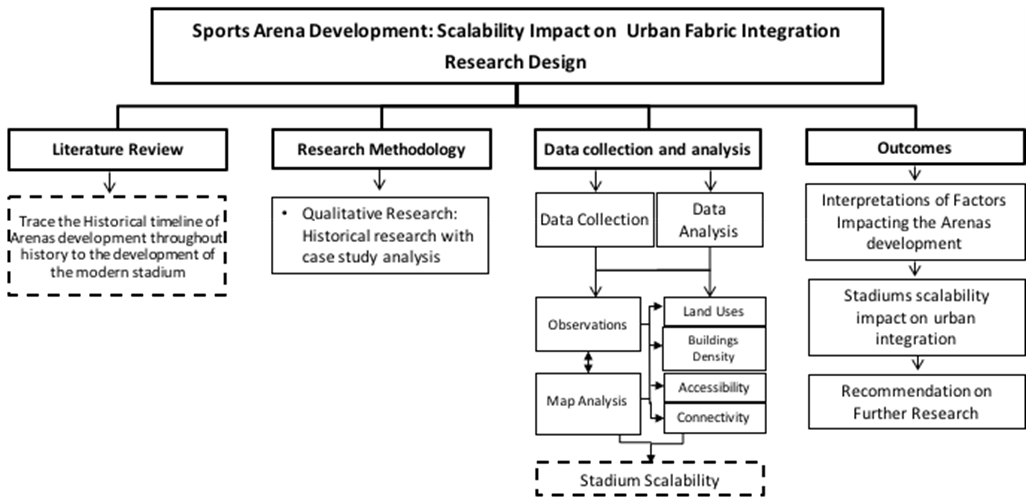

3. Methodology

- It is important to further examine the integration of arenas into modern urban development. From the literature review discussed above, it is apparent those arenas were an integrated part of ancient cities due to its natural structure. however, arenas in post modernism period failed to be integrated by becoming bigger and isolated. The evolution of arenas has a significant impact on its integration in the urban fabric of recent developments.The study aims in answering the following questions: 1) What did impact the development of arenas as a building type? 2) How the urban fabric is impacted by stadiums scalability? Method used in this study is based on historical qualitative research method and case study comparison (See the data is collected from primary and secondary resources and the data collection methods were based on observations and map analysis. The data is then analyzed through four variables: land uses, building density, accessibility and connectivity. The data collection and analysis outcome is interpreting the factors impacted arenas developments, and the impact of stadium scalability on urban integrations. it is important to note that arenas mentioned are sport related only.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Development of Arenas as a Building Type

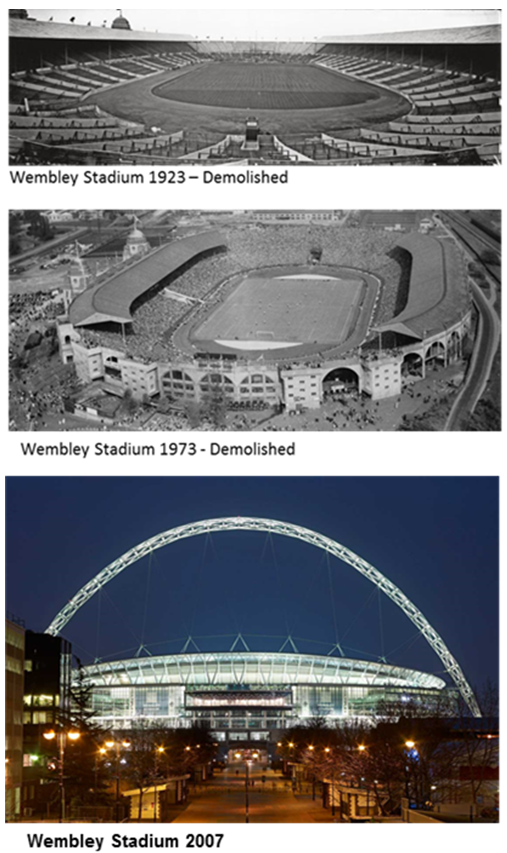

- Advances in technologies played an important role in the development of arenas that can be seen in the five generations theory developed by Sheard (2005). In addition to the surpassing human needs, the development of building materials impacted arenas development. For example, introducing the roof to the arena helped in making the arenas weather resisted, however, the original need of the roof was raising when the old terraces were replaced by seating. While seating took much more space, the need of a bigger roof to support the structure and provide shading was a must (King, 2010).In addition, the development of new modes of mobility created more opportunities in different stadium site. The site selection decision has also impacted the development of arenas as a building type. There are three main sites locations: 1) Urban locations, with advance transportation network but stadium developers can face space limitation and a higher coast. 2) Semi-Urban locations, that can have a lower cost but larger space for other developments such as parking spaces. 3) Greenfields locations where land cost are mostly the lowest but larger spaces are available, however it is mostly linked with a poor transportation network (Union of European Football Associations, 2012).In one hand, new stadium development developers might favor semi-urban locations for its ability to accommodate accessibility and a larger development, the urban and Greenfields location can on the other hand play as a catalyst for urban regeneration. Images of Wembley Stadium in the United Kingdom is showed in figure 3. The images show the transformation of the standing arena in 1923. In addition, it shows the introduction of the seats, the roof, and the glass façade in 2007. In 2003 the stadium was demolished and re-built in 2007 with its new increased 90,000 capacity that made it an urban landmark (Stadium Guide, n.d).

| Figure 3. Sources: http://www.stadiumguide.com/wembley & http://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/wembley-stadium |

4.2. Stadium Scalability: Choosing Between Scaling up or down A Stadium

- While the development of arenas throughout history was driven by oppressing needs. Arenas have always been subject for development. Ultimately arenas were either scaled up by adding new structures such as the roof, seats, screens...etc. or by developing it as multifunction arenas with flexible structure to accommodate different uses. additionally, scaling down arenas was not always an option, before modular stadiums, stadium downsizing was either by the complete demolishing of an existing or a temporary structurer for a bigger or development. While scaling up and enhancing existing arenas have been the call to revitalized un-used and abundant arenas, many factors impacted the making of this decision and its future outcome. Financing the arena redevelopment project and its integration to the existing fabric are two major factors impacting the decision of scaling up an arena. While financing impacts the initial scaling up decision, elements such as connectivity, accessibility, building densities and land uses of the existing urban fabric impacts the final integration outcome. Khalifa international stadium in one of Qatar 2022 world cup stadium that is currently being scaled up to accommodate 40,000 spectators in 2022 is discussed in the next part of this research. Moreover, the decision to scale down a stadium have not been always an option. Question on the economics of demolishing or downsizing a stadium from the building cost against any possible revenue arise to the stadium stakeholders. Organization such as the FIFA suggest the use of modular seating to allow more flexibility on scaling down or up a stadium according to it needs without impacting its original structure. While urban integration is a common factors impacting the decision of scaling down or up a stadium, lack of utilization and low demand impact the decision of scaling down a stadium or using modular seating to avoid abundance. Failing to integrate a stadium to its surroundings raised the need to question the possible benefits of scaling down a stadium to fit to its urban surrounding and utilization needs. While scaling up a stadium is impacted by the availability of financial support, scaling down a stadium can be driven by the stadium low utilization and demand as another option to demolition. However, in both ways the stadium is impacted by its ability to integrate to its surrounding through connectivity, accessibility and its fitting to the existing building densities and land uses.

4.3. Case Studies: Khalifa International Stadium vs. Qatar Foundation Stadium

4.3.1. Khalifa International Stadium

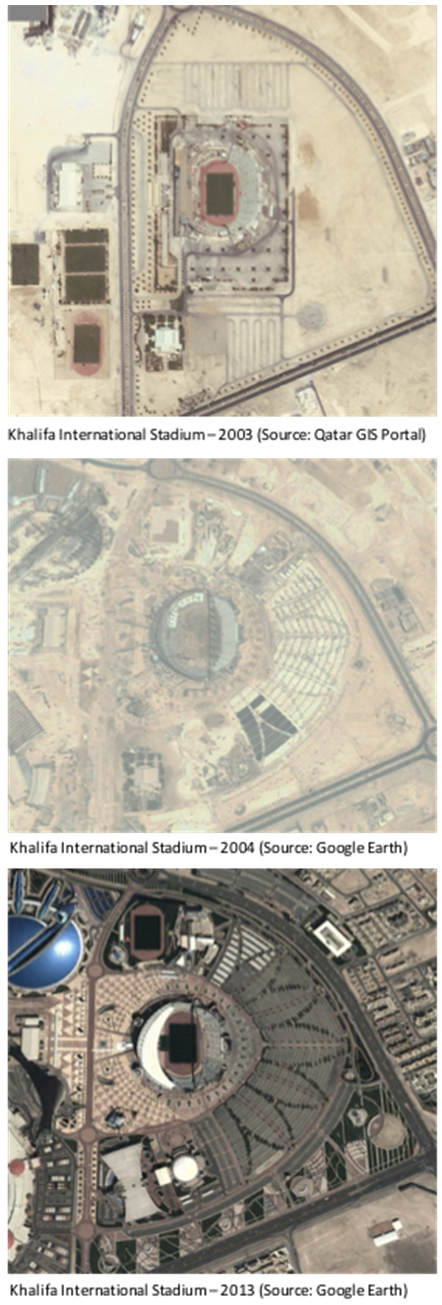

- Khalifa international stadium is Qatar national stadium and was built in 1976. The Stadium holds significant legacy of Qatar football history (SC, n.d.). Figure 4 shows the redevelopment of Khalifa International Stadium between the period of 2003-2013. The stadium was redeveloped firstly in 2003 to host the 2006 Asian games, the new development is shown in 2004 satellite image. The stadium is now in its second redevelopment project in preparation for the 2022 World Cup to meet the FIFA standards. The stadium original capacity is 20,000 seats, the renovation is intended build a bigger stadium by increasing it capacity to 40,000, in addition for a new cooling system (SC, n.d.).

| Figure 4. Khalifa Stadium 2003-2013 |

4.3.2. Qatar Foundation Stadium

- Qatar Foundation stadium is located within the education city south campus. The capacity of the stadium will be 40,000 during the world cup and will be reduced to 25,000 seats for its legacy mode (SC, n.d.). The modular seating will be disseminated post the event and sent to developing countries that is in need for sports infrastructure (SC, n.d.). The stadium and its precincts will include outdoor and indoor playing fields such as football, tennis courts, swimming centres and other non-sport uses such as retail shops (SC, n.d.). The stadium and its precinct legacy will be defined for being a hub for sport and recreation for not only Qatar Foundation but the local community.While the integration of a stadia through upscaling can bring many benefits. Cases such as Qatar Foundation stadium shows that the ability to down size a stadium can benefit districts where its community focused such as the education city south campus, targeting the district local population. Being a knowledge, education and health hub, AlShaqab district (Known as Education City) attracts many students, research and locals to uses its different campuses and facilities. In a daily basis. Qatar Foundation is the owner of the Qatar Foundation stadium and a key stakeholder in the administration of the Shaqab district. This helped in increasing the connectivity of the area through pedestrian and cycling pathways similar to Aspire Zone, in addition to other alternative modes such as the tram. In addition, the existing building density regulations is allowing a low building density (MMUP, 2013).The main challenge facing scaling up the stadium or keeping it at 40,000 capacity is accessibility. Although inner concentricity and accessibility is not a problem. Serving the local need in the day-to-day utilization can bring more benefits for the surrounding local district. Currently work is in the progress for developing of Khalifa Avenue. The Avenue will be connecting Dukhan to Doha. In addition, Al Rayyan Street is also being redeveloped to become Al Rayyan Highway and another accessible route to AlShaqab district.

4.3.3. Case Study Summary

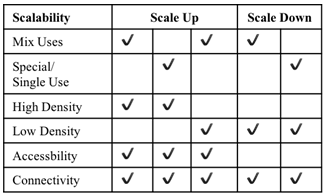

- Stadium scalability and its integration to the urban fabric is impacted by four urban elements. First of all, is land uses regulations of the stadium district. While mix uses districts promote diversity of activities and attract a diverse population, it requires a more complicated transport network, that can benefit from scaling up a stadium or increasing it capacity. Second of all, is the district urban form, while high to medium density regulation can support a bigger stadium structure, low density areas can benefit from scaling down a stadium to fit it existing urban form. Thirdly, stadium accessibility is also impacted by the district land uses and its ability to accommodate a complex transport network, however, in some cases where a special use district is connected through a complex transport network, the stadium is then have an opportunity to be scaled up as well, if it has high or medium building density. The fourth and final element is connectivity. Connectivity in all of the design scenarios is considered an important scalability factor. Without connectivity the stadium scaled up or down will not be able to be fully utilized. Table 1 shows the possible scalability scenario based on the four urban design elements: land use, building densities, accessibility and connectivity. On one hand, Khalifa International Stadium upsizing based on the table is supported by the district diversity of uses, accessibility and connectivity, although the area is low density. Another possible scaling up scenario can also happen if the area is a single use district but high in density, for example, a tourism or sport based district. Qatar Foundation stadium in the other hand, is more likely to succeed in the scaling down scenario. Either if it’s a mix uses or a single use district, low density district with a simple transport network can benefit the most with the scaling down scenario.

|

5. Conclusions

- This paper examined the factors impacting the development of arenas as a building type, and the impact of stadium scalability on the urban fabric. Through the development of the Literature review to trace the historical timeline of arena development till the modern stadiums, to the Khalifa international stadium and Qatar foundation stadium analysis, in order to answer the following questions: what did impact the development of arenas as building type? And how the urban fabric is impacted by stadiums scalability?While arenas developed throughout history to support social needs such as places for entertainment, recreation and others. The development of arenas as a building type was impacted by the advancements of technology that is seen in the development of building materials and modes of mobility. Both factors impacted the development of the modern stadium to become bigger and isolated from its urban surroundings. advancements of technology therefore impacted the development of arena as a building type but proposed challenges for its integration in the urban fabric.While becoming bigger and more isolated, the stadium scale was but in question on its urban form fitting. Stadiums scalability therefore is impacted by the district land use regulations, building densities accessibility and connectivity. The important of the stadium scalability is not exclusive for new stadiums development, but it’s also an important question for all under-utilized stadiums. The results show that if a district regulations allow mix-uses, high density, accessibility and connectivity, upscaling a stadium can then help in a better integration with its surroundings. And if a districts regulations allow single-use, low density, connectivity and is faced with limited accessibility, downscaling a stadium can then help in a better integration with its surroundings.Further research can be done on stadium flexibility and its adaptability to its surrounding. This research focused on the stadium scalability and the impact scalability has on urban fabric integration. However, further study can be done on options for stadium scalability such as in the case modular seating. Finally, stadium unlike any other buildings require far more urban design consideration to fully function as a vital district organ.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I (Amna Aljehani) would like to thank Architect Samantha Cottrell for sharing her knowledge on an earlier work that helped on the formulation of this paper research question on stadium scalability.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML