-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2016; 6(6): 131-141

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20160606.01

Method of Scoring for Evaluating Borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes: Superposition Mapping and Proposed New Borders

Barış Ergen 1, Zeynep Ergen 2, Burçak Yüksel 3, Erman Ağmaz 4

1Department of City and Regional Planning, Bozok University, Yozgat, Turkey

2Department of Architecture, Erciyes University, Kayseri, Turkey

3Ankara Province Coordinator, Agricultural and Rural Development Institution, Ankara, Turkey

4City Planning Department, Hacılar Municipality, Turkey

Correspondence to: Barış Ergen , Department of City and Regional Planning, Bozok University, Yozgat, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this study analyzes and evaluates the performance of borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes. Hürmetçi Marshes is affected by pressure of urbanization process of Kayseri; this urbanization process causes contamination and environmental deterioration. Research question is how we can reduce the negative effects of urbanization by proposing borders in Hürmetçi Marshes. Great Soil Group, Land Use and Vegetation, Slope, Erosion, and Land Use Capability Class data from the Identification and Improvement of Problematic Agricultural Areas Project of 2012 were used in the evaluation of wetland borders by scoring superpositioned data within the borders determined for the Hürmetçi Marshes by the National Wetlands Commission. It is considered, as a result of this evaluation, that the wetland ecological border determined in 2006 should be larger, an ecological impact zone should be determined and a primary conservation zone should be established. The primary conclusion is that it is necessary to establish an absolute conservation zone within the identified borders of the Hürmetçi Marshes and an ecological reserve area, where no uses are allowed, in the ecological zone. Another conclusion is that wetland management studies, in addition to the evaluation of baseline data, need to be carried out for the conservation of wetlands within a set of borders. Furthermore, an important conclusion is that urban functions need to be restricted within the ecological impact area and the primary conservation area.

Keywords: Wetland, Borders, Scoring Method, Superposition Mapping, Hürmetçi Marshes

Cite this paper: Barış Ergen , Zeynep Ergen , Burçak Yüksel , Erman Ağmaz , Method of Scoring for Evaluating Borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes: Superposition Mapping and Proposed New Borders, Architecture Research, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 131-141. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20160606.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- “Wetlands have an integral relationship with watersheds and ecological health [1]”. “Wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems in the World [2]”. Beside wetlands are most sensitive areas in urban and rural ecosystems. In the planning process, protected areas for positive discrimination should be established to maintain the sustainability of the sensitive and the vulnerable. Public benefit is the key point in the positive discrimination and the maintenance of the sustainability of sensitive areas. Besides defining borders is the first step for managing sensitive areas. Steele et al [3] mention in their study in 2013 that the longest border in planning in Australia is found between theory and practice. The most important problem in planning, specific to the sustainability of sensitive areas in Turkey, is the contradictions existing between t heory and practice. All parties are in agreement in theory on the importance of the conservation, maintenance and sustainability of sensitive areas, but it is clearly seen that those areas cannot be protected in practice. Therefore, it would not be erroneous to state that invisible borders exist in the failure to protect those areas. Planning is made up of borders [4]; and Borders either confirm differences or disrupt units [5]. Borders are in ‘a process, or series of spatial events, best understood along a continuum of possibilities . . . [of] multitextual and multi-purposeful bounding activities’ [6,=7]. The development in border studies is important in deepening our understandings of the interactions of ecological construction and scalar formation [6]. The continuum possibilities of slope, soil groups, land use, erosion, and land use capability classes data should be defined the borders of wetlands therefore these data are examined in this paper. These data will superpose and according to these data borders will be evaluated in Hürmetçi Marshes.“If all the world is a stage, then borders are its scenery, its mise en scène, its ordering of space and action, wherein actors and observers must work at making borders intelligible and manageable, and must do so in order for the drama to proceed [5-8].”In this study, the actors are the borders that determine the land use, urban development, actions and places, and the “drama” is the sustainability of the Hürmetçi Marshes. Borders need to be accurate and definite so that they can be managed intelligently, and, in the meantime, the “drama” should be successful. For the success of the drama in the Hürmetçi Marshes, a sensitive area, the baseline data must be evaluated accurately. In this study evaluating the borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes, the following questions comprise the starting points of analysis:1- Are the borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes in agreement with those identified by evaluating the baseline data? 2- Are the land use decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan within the borders of the Hürmetçi Marshes accurate?3- How should the borders be determined that are required to achieve protection and sustainability in the Hürmetçi Marshes?

1.1. The Hürmetçi Marshes

- The Hürmetçi Marshes is an important wetland on the migratory routes of birds. Its importance was not adequately recognized until the 2000’s and was better acknowledged in 2006 upon its inclusion in the scope of the national wetlands study. The Hürmetçi Marshes, extending out from the foot of Erciyes Mountain, is a wetland consisting of ecosystems such as marshes and wet meadows [9, 10]. In the study by Nilgün Karadeniz et al [11], the Hürmetçi Marshes was identified as one of the important wetlands in Turkey. The Hürmetçi Marshes is located 13 km southwest of Kayseri Province, within the borders of the districts of Hacılar and İncesu. It is bounded by the Kayseri-Adana highway to the north, Erciyes Mountain to the south and an industrial estate to the east [9, 12, 13]. According to the explanatory report of the 1:100,000 scaled environmental zoning plan, the Hürmetçi Marshes is an area harbouring important biological richness and with a potential for nature tourism [14]. “The Hürmetçi Marshes Wetland is comprised of wetland habitat, a shallow fresh water lake with boundaries fluctuating seasonally, wet meadows and marshes. Saline steppes extend beyond the area; these are thought to have formed by the receding water surface, which used to cover a much larger area. Agricultural lands (wheat, barley, etc.) surround the villages in the vicinity of the area. The wet meadows are used as pasture (for water buffalo grazing) in certain periods of the year. Steppe habitat is found in the nearby hills. The lake area is important not only because it comprises an important main habitat for water birds, but also because it harbours aquatic vegetation providing suitable habitat for the reproduction of the fish that is consumed by these bird species. Another habitat type found in the area is wet meadows.” [15].“The area is part of the Karasaz Plain. The important water resources are the Vanvanlı Creek and Dokuzpınar Creek, located to the south of the marshes. The Vanvanlı Creek joins Dokuzpınar Creek and the drainage canal coming from the Sultansazlığı Marshes at the northwest of the Hürmetçi Marshes, thus forming the Karasu Creek. The Karasu Creek leaves the Hürmetçi Marshes from the northeast corner of the marshes, and drains into the Kızılırmak River. The maximum depth in the marshes is 1 meter, and the depth and the spread of the marshes fluctuate seasonally. Until 1957, the Karasu Plain was a semi-closed basin, covered with marshes throughout the plain. The marshes are limited to the northeast of the area at the present, as a result of the draining of the plain, via the Karasu Creek, into the Kızılırmak River in 1957 [12]”. The drainage project, completed in 1957, contributed to the drying of the Hürmetçi Marshes and caused a reduction in the surface area of the shallow lake. “The lack of knowledge on the Hürmetçi Marshes brings about its destruction [10]”. The Hürmetçi Marshes was reported in 2004 to be an Internationally Important Wetland by the General Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry [16]. The protection zones for the Hürmetçi Marshes were determined in 2006, as required by the Regulation on the Conservation of Wetlands and approved by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in the National Wetlands Commission on 20 June 2006 [9]. The preparation of the Hürmetçi Marshes Management Plan was put out to tender on 24 May 2011 [17]. The management plan for the wetland was completed and put in force in 2012 [18]. In her study in 2007, Kurtaslan-Öztürk [13] reported the problems facing the Hürmetçi Marshes due to urban development in five headings. The first problem is the presence of an industrial estate adjacent to the marshes and the impacts of the industrial pollutants on the marshes. The second is the presence of a carbon dioxide plant within the marsh area and the adverse impacts of CO2 production on the ecosystem. Another problem in the area is poaching. The agricultural activities in the irrigated and the non-irrigated fields also affect the area adversely. Other problems include intensive grazing and the rooting out of vegetation in the meadows for use as grass in the city. According to the study titled “A Quick Scan of Peatlands in Central and Eastern Europe” by Minayeva, Sirin and Bragg in 2009 [19], the Hürmetçi Marshes was identified as an important peatland near the lake. That study was the first on the ecological importance of the Hürmetçi Marshes having a different perspective. The previous studies mention the importance of the water birds in the Hürmetçi Marshes, the location of the marshes on the migratory routes of birds, and the wet and brackish ecosystems. The study by Minayeva, Sirin and Bragg [19] 2009 pointed out the different and significant roles (peatland) of the Hürmetçi Marshes in the ecosystem. The presence of the CO2 plant for beverage actually indicates that this area is an important peatland. The peatland character presents variations in the soil properties and contributes to the carbon cycle in the Hürmetçi Marshes.

2. Methodology

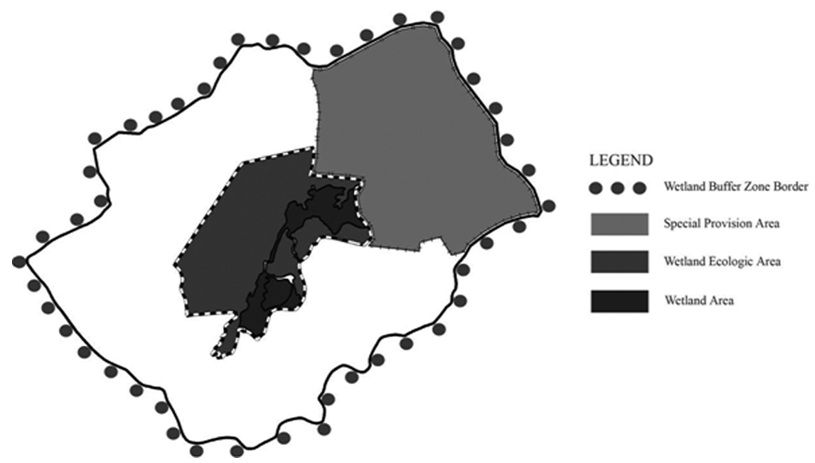

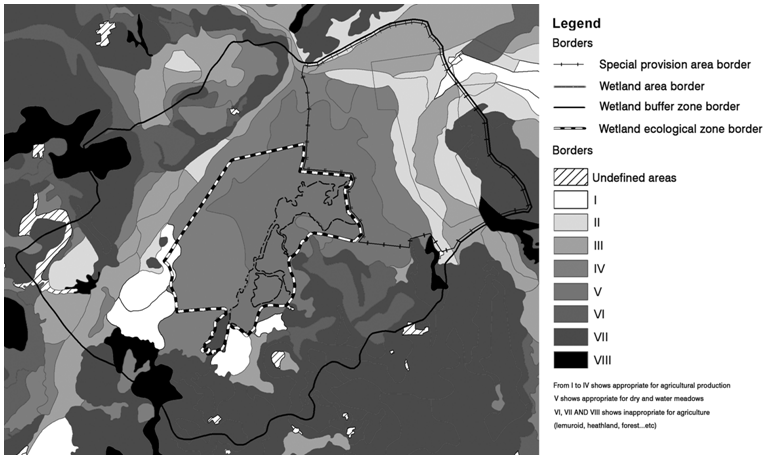

- Methodology of paper comprises a comprehensive study on the performance of borders of Hürmetçi Marshes with superposition of Great Soil Group, Current Land Use, Slope, Erosion Intensity, Land Use Capability Class, and Evaluation of the Land Use Decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan. In this study, data, in 1:25000 scale, from the Identification and Improvement of Problematic Agricultural Areas Project of 2012 (source from Ministry of Agriculture) were evaluated. The data collected by the Identification and Improvement of Problematic Agricultural Areas Project include detailed ecological data such as land use, slope, soil groups… etc. These data has been also used in Management Project of the Hürmetçi Marshes. The data included great soil group, land use, erosion intensity, land use capability class and slope analysis data, and their potential contribution to the ecosystem toward the sustainability of the Hürmetçi Marshes was assessed. The borders required for the ecological sustainability of the Hürmetçi Marshes were re-evaluated in those five aspects. The scoring method was used to re-evaluate the borders. In the re-evaluation of the borders, the properties required for the sustainability of the Hürmetçi Marshes, as specified by the five aspects mentioned above, were scored according to their superpositioning. New borders were proposed in the Hürmetçi Marshes on the basis of the results of this scoring. Detailed evaluation of the baseline data is an essential requirement in identifying borders in areas, particularly with sensitive ecosystems such as wetlands. In a wetland exhibiting peatland characteristics, the baseline data required to be investigated in detail are the soil groups to identify the organic soil properties, the land use capability class to determine the productivity of the land, the erosion intensity in relation to land cover and yield, the slopes to determine the water catchment basin, and the current land use to identify the existing land uses that need to be continued. In this study, the scoring method was used to identify new borders. This analysis was carried out by superpositioning the soil group, erosion intensity, slope, land use and land use capability class data representing wetland characteristics, and then identifying a set of new borders according to the obtained scores, from the highest to the lowest.The borders of the Hürmetçi Marshes approved by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in 2006 were superimposed upon the Environmental Zoning Plan approved by the Greater Municipality Council in 2010. Those borders are the wetland buffer zone border, the special provision area border, the wetland ecologic area border and the wetland area border, respectively. The special provision area grants the required special provision for the establishment of the industrial estate. The borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes are presented in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. The Borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes |

| Figure 2. The Satellite Image of 2013 of the Hürmetçi Marshes. Source: Archive of Hacılar Municipality |

2.1. Great Soil Group (Presence of Organic Soils)

- The data from the Identification and Improvement of Problematic Agricultural Areas Project were used to identify the great soil groups, and especially the areas in which there are mostly organic soils rich in carbon (C) compounds. Thus, the organic soils and the parts of the Hürmetçi Marshes with peatland character were identified. Furthermore, the parts of the wetland through which surface waters pass would also be identified by their alluvial soils, since these soils are comprised mostly of transported sediments. The conservation of the areas surrounding the surface waters would prevent water pollution and facilitate the maintenance of the wetland characteristics of the Hürmetçi Marshes. The soil group data were not provided in the areas crosshatched in Figure 3. In this figure, the areas with organic soil groups are shaded with lines at a 45º angle. The wetland area (the surface area of the lake expanding and shrinking seasonally) and the ecologic area consist almost entirely of organic soils. However, the areas having organic soils cover an area larger than the ecologic area, and the special provision area is also partly within the organic soils area. The areas marked with dots in this figure are the alluvial soils. The eastern part of the special provision area lies within the alluvial soils area. The evaluation of the borders with respect to soil groups indicates that the borders of the organic soils area and the alluvial soils area should comprise the ecologic area border (the absolute protection area).

| Figure 3. Distribution of the Great Soil Groups in the Hürmetçi Marshes |

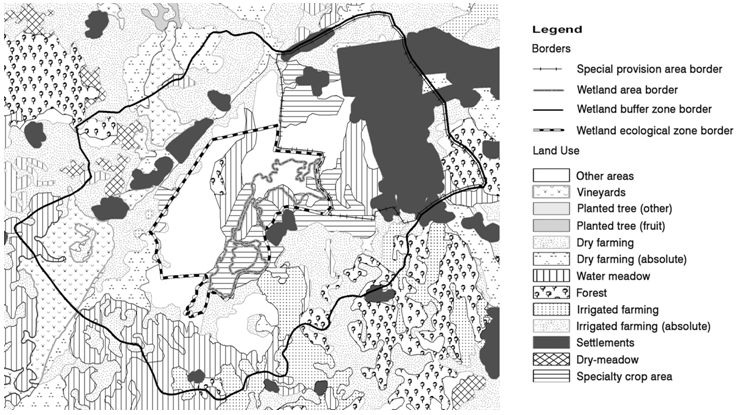

2.2. Current Land Use (Land Cover)

- The current land use data are important, especially for identifying the areas of agricultural and animal husbandry activities and settlements. The current land use data identify the planted areas, the pastures and the meadows. The current land use data are important in identifying the current uses of the land and the agreement (or the concordance) of the existing uses within the borders of the Hürmetçi Marshes, as well as for resolving potential problems related to land use. The dark grey areas in the current land use figure (Figure 4) indicate the settlements. There are many uses, such as residences, small-scale industry and organized industrial estates within the settlements. It can be seen (in Figure 4) that the speciality crop areas and the meadows comprise a large portion of the wetland ecologic area. The white areas in Figure 4 are the other areas for which land use is not defined. There are irrigated and non-irrigated agricultural areas to the west, northwest, north, south, southwest and southeast of the ecologic area border. Thus, the ecologic area is burdened by agricultural activities from its northern border to the southeast border in a counter clockwise direction. Furthermore, there is pressure from the settlements to the east of the Hürmetçi Marshes. The evaluation of the current land use data within the borders indicates that the borders of the meadows and the speciality crop areas should also comprise the ecologic area border (the absolute protection area).

| Figure 4. The 2012 Land Use in the Hürmetçi Marshes |

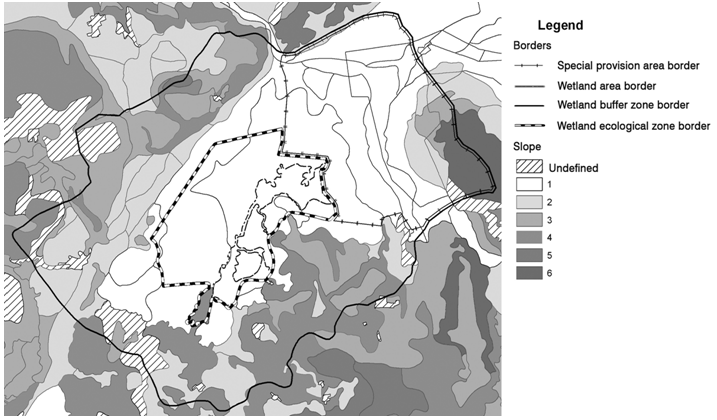

2.3. Slope

- In terms of slope, the Hürmetçi Marshes can be described as a large bowl. As it can be seen at the figure 5 the middle part of the area is level ground with the least slope. The level ground accommodates the pooling of water, forming the lake surface and subsequently allowing the habitation of the area by birds. The slope is one of the most important factors determining the formation, in ecologic terms, of the Hürmetçi Marshes. The sloping of the area is in the north and in the south and flattening in the middle allows for the accumulation of organic matter in the level parts, thus providing for the concentration of fertile alluvial soils in those parts. It eventually results in the formation of ecologically rich resources and habitats for many species. The slope also allows for the arrival of ecological contributions from the Erciyes Mountain located to the southwest of the Hürmetçi Marshes. The waters running down and infiltrating from the Erciyes Mountain reach the Hürmetçi Marshes as both surface water and groundwater. The surface waters erode the volcanic rocks of the Erciyes Mountain, and these rock fragments contribute to the formation of fertile alluvial soils when they reach the Hürmetçi Marshes. The evaluation of the borders in terms of slope indicates that the areas of Class I slope (least slope) should be within the ecologic area border (the absolute protection area) to facilitate the continuity of the favourable ecological contributions from the Erciyes Mountain.

| Figure 5. Slopes in the Hürmetçi Marshes |

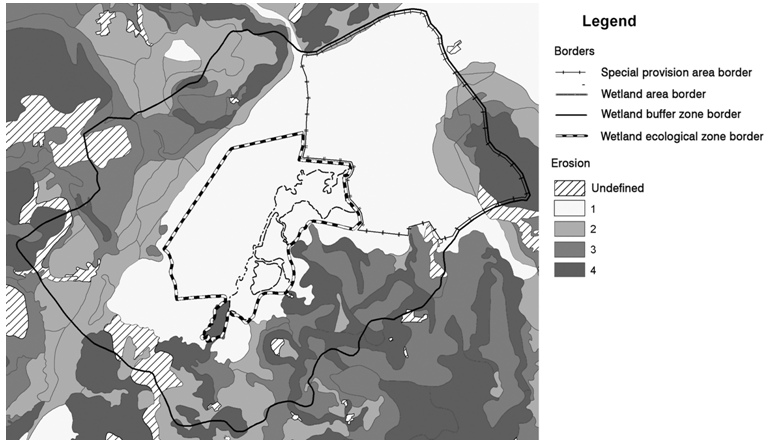

2.4. Erosion Intensity

- The erosion intensity and the slope data in the Hürmetçi Marshes will enable the evaluation of the area in terms of intensive agricultural activities and intensive grazing in animal husbandry, particularly with respect to the control and prevention of their potential adverse impacts. The erosion intensity in the Hürmetçi Marshes is presented in the figure below (Figure 6). The areas shaded with 45º angle lines represent areas in which the erosion intensity is not defined. The degree of erosion intensity, also considering the slope and the agricultural activities within the buffer zone of the Hürmetçi Marshes, indicates that the ecologic area is burdened by erosion from its northern border to the southeast border in a counterclockwise direction. In particular, the ecologic area border and its vicinity and a large part of the special provision area can be considered fortunate in terms of erosion intensity. It is of vital importance that the vegetation cover in these areas is protected. Therefore the borders of the areas having the least erosion, identified as Class I erosion intensity, should be defined as the borders of the ecologic area (the absolute protection area).

| Figure 6. Erosion Intensity in the Hürmetçi Marshes |

2.5. Land Use Capability Class

- The land use capability class is important, especially in terms of the suitability of the lands for agricultural production. Thus, using these data, the agricultural areas proposed in the Environmental Zoning Plan were evaluated for suitability for agricultural production, and the areas not suitable for agricultural production were proposed for protection. In terms of land use capability class, the soils having the classes I, II, III and IV represent the lands suitable for agricultural production. Class I lands are the most suitable for and the most valuable in terms of agriculture. Class VI, VII and VIII lands comprise the unfertile lands not suitable for agriculture, and suitable for use as forest, maquis and shrubs. By superpositioning the land use capability class with the current land use, it can be seen that the existing agricultural lands within the buffer zone of the Hürmetçi Marshes, especially the lands from the northern border of the ecologic area to the southeast border in a counter clockwise direction, are not suitable for agriculture in terms of land use capability (see figure 7). Cultivation would lead to the intensification of erosion in those areas and to significant damage to the ecologic system due to the loss of vegetation cover. Upon an examination of the data in the central part of the Hürmetçi Marshes, it can be seen that those areas are mostly comprised of Class IV and Class V lands. Class V lands are particularly suitable for use as pastures and meadows. Pastures and meadows, together with marshes, provide suitable conditions for inhabitation by migratory birds. Therefore, upon the evaluation of the borders in terms of land use capability class, the areas identified as Class IV and V should be within the ecologic area border (the absolute protection area).

| Figure 7. Land Use Capability Classes in the Hürmetçi Marshes |

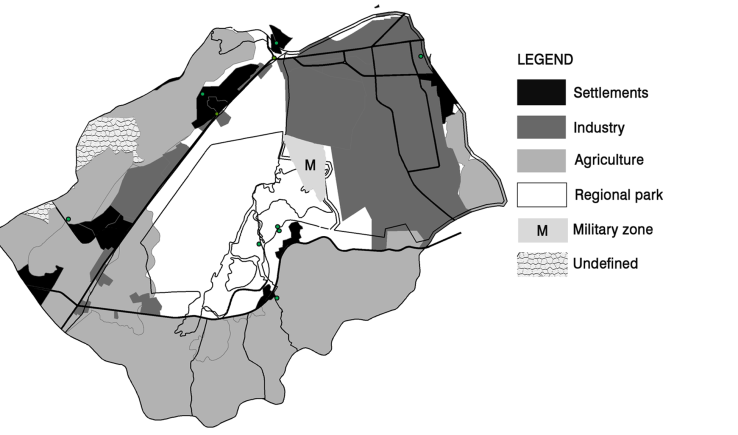

2.6. Evaluation of the Land Use Decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan

- The agreement (or concordance) of the slope, erosion intensity, land use, great soil group and land use capability class data with the Environmental Zoning Plan was investigated in regard of the sustainability of the Hürmetçi Marshes. In the 1:25000 scaled Environmental Zoning Plan had been confirmed in force by Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality since its approval in 2010, the land use decisions are considered in four aspects, and the zoning is also in four levels. These four main zoning decisions are 1) decisions regarding the settlement areas and the regional park, 2) decisions regarding the agricultural and forest areas, 3) decisions regarding the technical infrastructure and 4) decisions regarding the industrial areas (small-scale industry, organized industrial estate and free zone) and the warehouse areas. The zoning study comprising the main principles in the Environmental Zoning Plan is presented in Figure 8.In this figure, the black areas represent the existing residential areas and the areas designated for residential development. The dark grey areas are the industrial areas, the warehouse areas and the free zone. The light grey areas are the lands set aside for agricultural activities. The white area located in the centre of the buffer zone comprises the area defined as the regional park in the Environmental Zoning Plan. It can be seen in the Environmental Zoning Plan that the industrial areas and the organized industrial estate in the east heavily burden the buffer zone of the Hürmetçi Marshes. The lands along the Buffer Zone from the northern border to the southeast border in a counter clockwise direction are burdened by agricultural production. The lands designated as the regional park, including the parts within the Ecologic Area, are therefore threatened with the inability to conserve their natural characteristics. The designation as a regional park will result in recreational usage of the area by local people from the cities. The walking paths to be built for the visitors to wander freely about the area, the rest and picnic areas, the unnecessary and incorrect planting of trees, and the general overuse of the area will lead to the complete loss of the natural characteristics and the demise of the Hürmetçi Marshes. Furthermore, the recreational facilities to be built in the regional park are likely to be inundated periodically because the Hürmetçi Marshes has a natural cycle of expanding the lake surface area in the rainy season and shrinking the lake area in the summer months.

| Figure 8. The Main Land Use Decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan |

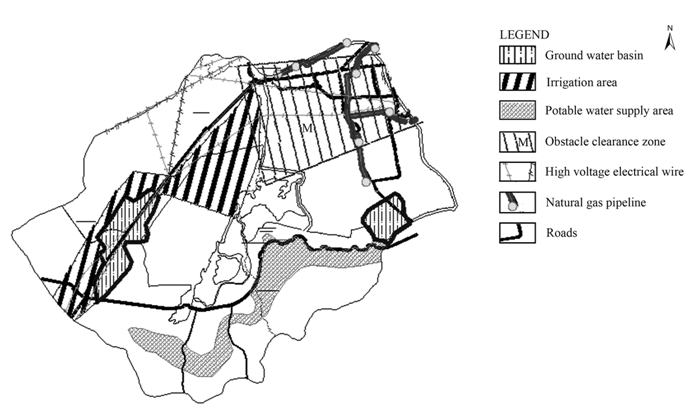

| Figure 9. Technical Infrastructure Decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan. Source: Archive of Hacılar Municipality |

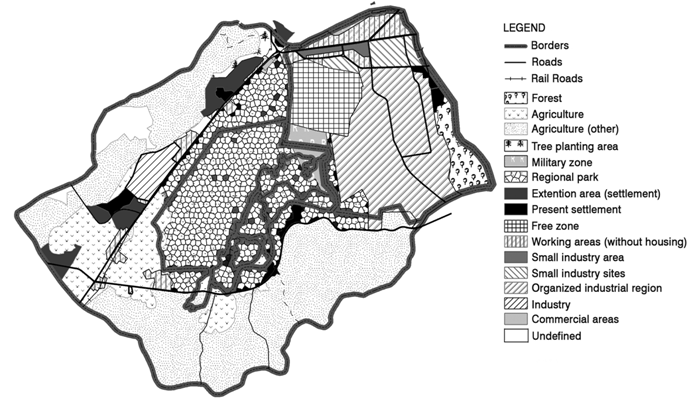

| Figure 10. The Decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan. Source: Archive of Hacılar Municipality |

3. Discussion: Evaluation of the Borders by Scoring

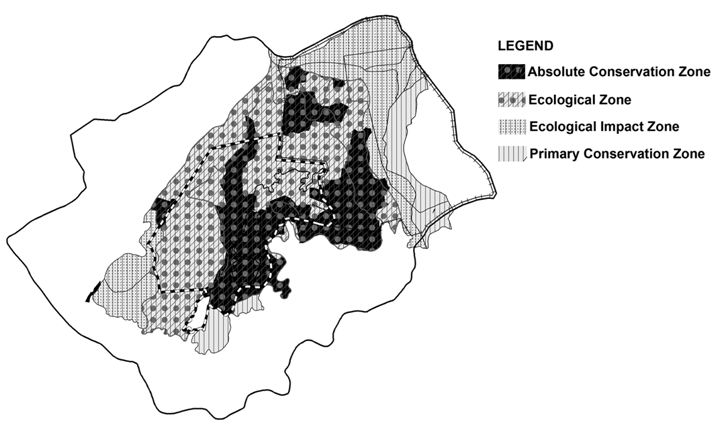

- “Urban ecology provides an ambiguous yet recurring connection between disparate fields of analysis and intervention [20]”. Intervention to Hürmetçi Marshes means that intervention to urban ecology of Kayseri. In this study, the borders within the Hürmetçi Marshes were evaluated in terms of great soil groups, slope, erosion intensity, current land use, and land use capability class. It was observed that the borders determined in 2006 and applied to the Environmental Zoning Plan in 2010 were actually not in complete agreement (or concordance) with the baseline data. However, it is obvious that, because of its distinct natural characteristics, the Hürmetçi Marshes is being heavily frequented by migratory birds. Therefore the borders should be revised upon an appropriate interpretation of the baseline data. In this study, the above-mentioned five baseline data sets are used, and new borders are proposed on the basis of the superpositioning and the scoring of the data. New protection zones in four levels are proposed as a result of this evaluation. The scoring criteria used as the basis for identifying the new protection zones are explained below. 1) Great Soil Group: In the evaluation of the borders, the organic soils were assigned two (2) points and the alluvial soils were assigned one (1) point.2) Current Land Use (Land Cover): The meadows and pastures and the speciality crop areas were assigned one (1) point.3) Slope: The Class I slope (least slope) areas, where the surface waters and the groundwater feeding the Hürmetçi Marshes accumulate and where the lake surface and the marshes are located, were assigned one (1) point.4) Erosion Intensity: The areas of Class I erosion (least erosion) comprising meadows, pastures and densely vegetated areas with rich soils experiencing no erosion problems (and contributing to the ecological richness) were assigned one (1) point.5) Land Use Capability Class: The Class IV and V lands where meadow vegetation exhibits wetland characteristics of the Hürmetçi Marshes were assigned one (1) point.In the evaluation, a scoring system was developed on the basis of the superpositioned data on the great soil groups, current land use, slope, erosion intensity and land use capability class. In this scoring system, each superposition was assigned a value of one point, except for the areas with organic soils for the great soil group. The organic soils group was assigned a value of two (2) points because the organic soils are the main elements of the peatland characteristics in the Hürmetçi Marshes. The areas scoring the highest were identified as the absolute conservation zone. According to this scoring system, the absolute conservation zone obtained a total score of six (6) points--two (2) points from the organic soil group and one (1) point each from the current land use, slope, erosion intensity and land use capability class data. The ecological zone border (the sensitive protection area) was identified with a total score of five (5), with two (2) points obtained from organic soils and one (1) point each from slope, erosion intensity and land use capability class. The ecological impact zone (the sustainable use area) obtained one (1) point each from the alluvial soils, slope and erosion intensity, scoring a total of three (3) points. The primary conservation zone was identified with one (1) point each from slope and erosion intensity data. No baseline data were superpositioned in the lands shown as white areas in Figure 11. Nevertheless, the land use in these areas should be controlled to maintain the sustainability of the wetland. In summary, new protection zones in four levels are proposed on the basis of the evaluation in this study; these are the absolute conservation zone, the ecological zone, the ecological impact zone and the primary conservation zone, respectively.

| Figure 11. Required Borders Proposed for the Hürmetçi Marshes |

4. Conclusions

- Wetlands have important role in urban and rural ecosystems. Borders are very important, though not so much emphasized, in urban planning. The identification of borders, the basic element in the conservation of sensitive areas and the implementation of plan decisions, is one of the most important factors in the success of the plans. Borders are important elements in protecting the sensitive characteristics of vulnerable areas and in maintaining the equity of these areas with the dominant areas. The method used in this study is based on scoring superpositioned data. This method reduces the time required to make planning decisions and to produce maps. By using this scoring system, a set of borders was proposed with a greater consideration of the baseline environmental data. It was demonstrated that the required borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes are the absolute conservation zone, the ecological zone (sensitive protection area), the ecological impact zone (sustainable use area) and the primary conservation zone (controlled use area), from the innermost section to the outermost, respectively. Starting with borders, conservation and land use policies urgently need to be determined to maintain the sustainability of the wetlands, the natural resources that are rapidly being destroyed. As demonstrated in this study, the mistakes made in determining the borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes led to further mistakes in the decisions of the Environmental Zoning Plan. Hence, there is a need for an approach that starts with borders and ends in area management. It is considered that this study will provide guidance for future studies and for the identification of conservation borders for a variety of areas such as the Hürmetçi Marshes that exhibit both wetland and peatland characteristics.

5. Recommendations

- The answers to the three questions that constituted the starting point of this study were obtained as a result of the evaluation described previously. The answer to the first question, “Are the borders in the Hürmetçi Marshes in agreement with those identified by evaluating the baseline data?” is negative. Therefore, an approach that considers the baseline data in determining the borders should be developed. Unfortunately, the answer to the second question, whether the land use decisions in the Environmental Zoning Plan regarding the Hürmetçi Marshes are accurate or not, is also negative. In this respect, the land use decisions should be more comprehensive and should consider the environmental sensitivity of the wetland. The answer to the third question, regarding the borders required to achieve protection and sustainability in the Hürmetçi Marshes, was obtained by scoring the superpositioned baseline data, as presented in Figure 11. Setting borders in urban planning is entirely an administrative issue; the plans are proposed for and implemented in the area within the border of authority. Therefore, the success of this study evaluating the baseline data and proposing optimum borders requires the development of proposals regarding wetland management as well. “Spatial planning strategies operating at multiple scales have in the last decade come to be viewed as key policy instruments for effective territorial governance [21-23]”. “In contrast to the limited scope of traditional land-use plans, it is argued that strategic spatial plans have the potential to act as frameworks for coordination across policy sectors and institutional arenas [21, 24-26, 23]”. In addition to the identification of borders, the capacity for the management of the Hürmetçi Marshes should also be evaluated for the responsible institutions. In this respect, an approach allowing for the coordination of the institutions related to the proposed land uses in the Environmental Zoning Plan is also required.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The Authors are grateful to anonymous reviewers for their comments that improved the manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML