-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2016; 6(4): 81-87

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20160604.01

Re-Visioning City: Discourse on Vision, Image and Memory

Mohammed Azizul Mohith, Syeda Tuhin Ara Karim, Hasnun Wara Khondker

Department of Architecture, American International University-Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Mohammed Azizul Mohith, Department of Architecture, American International University-Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

“As this wave from memories flows in, the city soaks it up like a sponge and expands. A description of [the city] as it is today should contain all [the city’s] past. The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.” – Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities. Therefore, the significance of a place lay not in its function, or even in its form, but in the memories associated with it. The most significant place for the city of today is to be the place associated with the collective memory of the city. Sometimes called cultural memory, the memory of the city is inextricably linked to the foundation of the city, and every general theory to find a meaning of a place must always be measured against this, especially in the present day of globalization where cities tend to have no boundaries. This paper tries to explore how visual perception through images or photographs can contribute to find the meaning of a place in a city. Buildings and institutions, streets and landscape, natural and artificial elements construct a new reading of the city as a system of representation, a complex cultural entity. This discourse brings together concepts from critical theory on vision, image and architecture of a city to find out a memory (or meaning?) depicted through photograph or image. The research expects to provide further analytical material on city dynamics and more authentic knowledge of variety of urban situations, thereby providing some necessary background on the historic urban culture of what a city may still hold.

Keywords: City, Image, Visual thinking, Memory

Cite this paper: Mohammed Azizul Mohith, Syeda Tuhin Ara Karim, Hasnun Wara Khondker, Re-Visioning City: Discourse on Vision, Image and Memory, Architecture Research, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 81-87. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20160604.01.

Article Outline

1. Rethinking City: Image, Vision and Memory

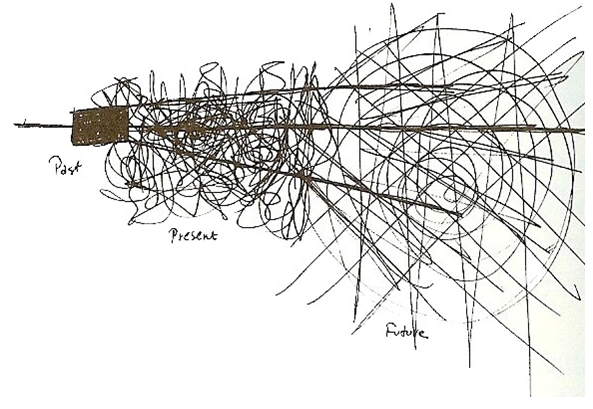

- Cities commemorate special pleasure for human memories through its historical yet common places being seen in all lights and weathers. A city is definitely a construction in space but unlike architecture the entity is of vast scale, which can only be perceived over long span of time. But for different people and for different instance the perceptions are of different sequence- interrupted, abandoned or cut across anonymously. ‘At every instant, there is more than the eye can see, more than the ear can hear, a setting or a view waiting to be explored. Nothing is experienced by itself, but always in relation to its surroundings, the sequences of events leading up-to it, the memory of past experiences.’ [1]. Even a visitor who may not have long associations with the city, can find the image of the city soaked with memories and meanings.Moving elements in a city, and in particular the people and their activities, are as important as the stationary physical parts. We are not simply observers of this spectacle, but are ourselves a part of it, on the stage with the other participants. Most often, our perception of the city is not sustained, but rather partial, fragmentary, mixed with other concerns [2]. Nearly every sense is in operation, and the image is the composite of them all. In case of a city it is obvious that the city is an object which is perceived (and perhaps enjoyed) by millions of people of widely diverse class and character and it is the product of many builders who are constantly modifying the structure for reasons of their own. As a result it may be stable in general outlines for some time but it is ever changing in detail.This critical research aims to analyze the perceptive reconstruction of cities eliminating its time barrier through visual memories. It will explore city dynamics in respect of visual thinking by image analysis. This analysis, however, limits itself to the effects of physical, perceptible objects on imaging. There are other influences on imageability, such as the social meaning of an area, its function, its history, or even its name. These phenomena will be explored in terms of finding meaning of simple but informative visual images. It will off course exemplify why the importance is given on images i.e. optical senses though other senses like hearing, touching or smelling might play cumulative role.

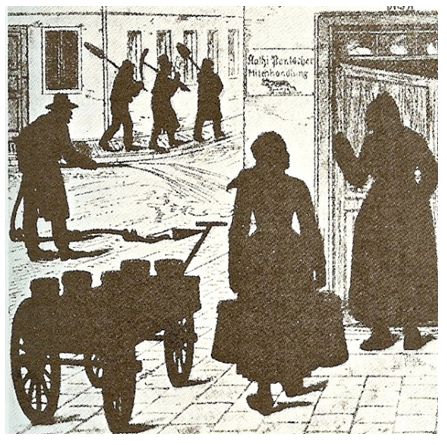

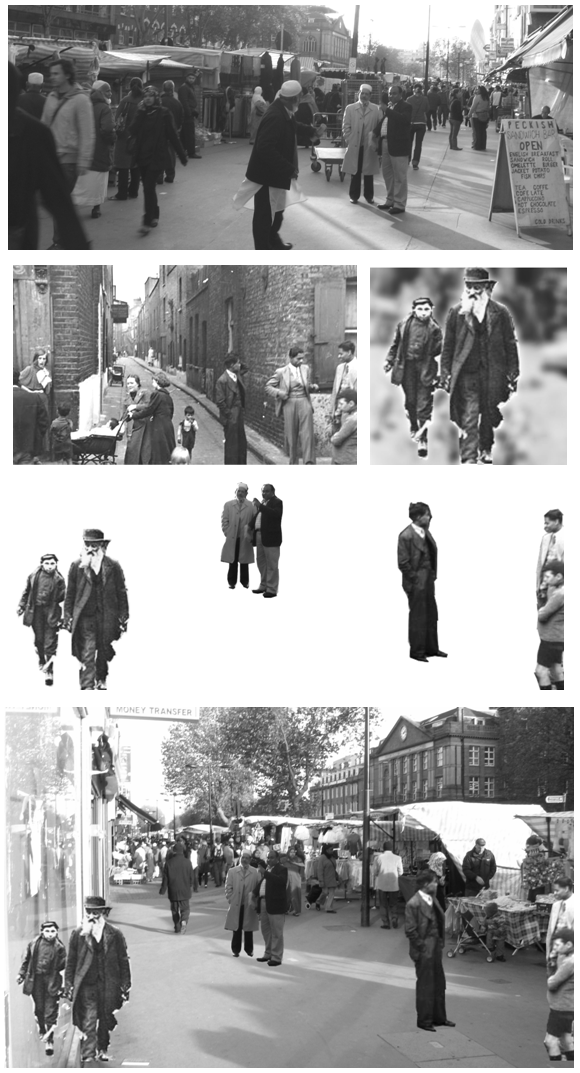

2. Vision and Thinking

- There seems to be a public image of any given city which is the overlap of many individual images. Each individual picture is unique, with some content that is rarely or never communicated, yet it approximates the public image, which, in different environments, is more or less compelling and embracing. [3] The contents of the city images so far studied (by historians and researchers), which are referable to physical forms, can conveniently be classified into people, structure and other representative identifiable elements.According to Juhani Pallasmaa sight has historically been regarded as the noblest of the senses, and thinking itself thought of in terms of seeing. [4] Already in classical Greek thought, certainty was based on vision and visibility ‘The eyes are more exact witnesses than the ears,’ wrote Heraclitus in one of his fragments. [5] Plato regarded vision as humanity’s greatest gift, [6] and he insisted that ethical universals must be accessible to ‘the mind’s eye’. [7] Aristotle, likewise, considered sight as the noblest of the sense ‘because it approximates the intellect most closely by virtue of the relative immateriality of its knowing’. [8]Since the Greeks, philosophical writings of all times have abounded with ocular metaphors to the point that knowledge has become analogous with clear vision and light is regarded as the metaphor for truth. Aquinas even applies the notion of sight to other sensory realms as well as to intellectual cognition.The impact of the sense of vision on philosophy is well summed up by Peter Sloterduk: ‘The eyes are the organic prototype of philosophy. Their enigma is that they not only can see but are also able to see themselves seeing. This gives them a prominence among the body’s cognitive organs. A good part of philosophical thinking is actually only eye reflex, eye dialectic, seeing-oneself-see.’ [9] During the Renaissance, the five senses were understood to form a hierarchical system from the highest sense of vision down to touch at the lowest. The Renaissance system of the senses was related with the image of the cosmic body; vision was correlated to fire and light, hearing to air, smell to vapour, taste to water, and touch to earth. [10] The invention of perspectival representation made ‘eye’ the centre point of the perceptual world as well as of the concept of the self. Perspectival representation itself turned into a symbolic form, one which not only describes but also conditions perception. Words associated with thinking also have visual roots: intelligent, idea, theory, contemplate, speculate, bright, brilliant and dull. And there is no shortage of commonly-used phrases which emphasize the primacy of the visual. Now a day the technological culture has ordered and separated the senses even more distinctly. Vision and hearing are now the privileged sociable senses. Analyzing images, therefore, considered as useful tool for exploring memory through vision.The idea of ‘vision and thinking’ in terms of observation has also been portrayed in the concept of ‘flâneur’- a term originally coined by Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) and refers to somebody who observes the city or their surroundings, and experiences an actual physical stroll but also is a way of philosophical thinking and a way of seeing/feeling things. According to Baudelaire, the flâneur moves through the labyrinthine streets and hidden spaces of the city, partaking of its attractions and fearful pleasures, but remaining somehow detached and apart from it. Baudelaire saw the flâneur as having a key role in understanding, participating in and portraying the city. [11]. Depicting the idea that flauneur provokes thinking and knowledge by visual recording Walter Benjamin wrote -That anamnestic intoxication in which the flâneur goes about the city not only feeds on the sensory data taking shape before his eyes but often processes itself of abstract knowledge – indeed, of the dead facts – as something experienced and lived through. This felt knowledge travels from one person to another, especially by word of mouth…” [12].

3. Image and Knowledge

- Aided by digital technology, designers and planners are making ever greater use of photographic images to depict and envision urban environment. The methods for employing photographs and their precise construction have not been adequately analyzed. Discussing the new reliance on imaging techniques in architecture, Cambridge Professor Andrew Saint recently noted, “the long-term challenge for the architectural profession is to ride this exciting, undisciplined, licentious, and dangerous beast, to control this irresponsible lust for image that pervades our culture.” [13] Several imaging methods have gained widespread currency in explaining public places. This essay specifically tries to explore the predominance of image over bodily experience; the exclusion of intertwined socioeconomic, historical and political specificity; and the commodification of place. It is to be believed that a photographic image can be used to articulate the impression of the present community image and build consensus for its history.However the trouble of such ideas lies in the definition of what constitutes a place. Sense of place incorporates a range of engaged bodily experiences in conjunction with passive appreciation of visual imagery. In any case image-based approaches to urban exploration can come up with revealed socioeconomic, historical and political realities.Can images hold meaning? If so, to what degree of precision can this meaning be predicted? Numerous theorists have examined this question in terms of painting and photography. According to photographer, philosopher Victor Burgin the photograph is an incomplete utterance of a massage that depends on some external matrix of conditions and presuppositions for its readability. That is the meaning of any photographic massage is necessarily context determined. We might formulate this position as follows: a photograph communicates by means of its association with some hidden or implicit text; it is this text, or system of hidden linguistic propositions, that carries the photograph into the domain of readability. [14]. Though, in any case differences in the cultural background of individual viewers cannot be discounted. According to Bazin, “Even the uncaptioned photograph, framed and isolated on a gallery wall, is invaded by language when it is looked at: in memory, in association, snatches of words and images continually intermingle and exchange one for the other; what significant elements the subject recognizes ‘in’ the photograph are inescapably supplemented from elsewhere.” [15] These ideas proposes the unavoidable presence of ‘something that is the outcome of visual senses’ to be conducted to understand a photographic image rather than to just looking at it.

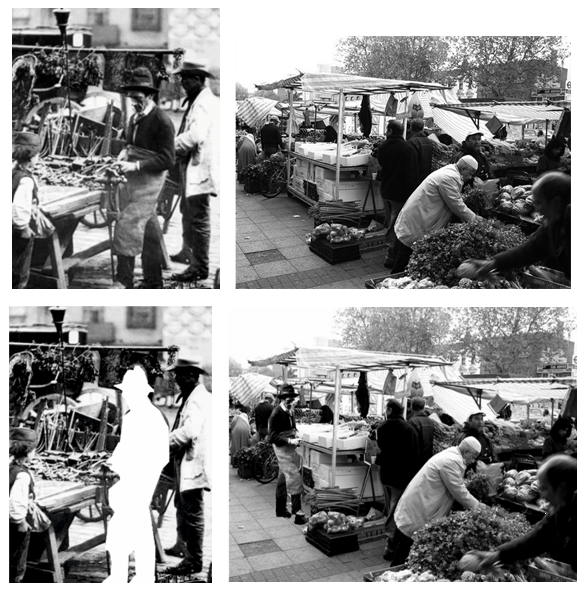

4. Analyzing Images

- A number of different approaches may be used to analyze photography. It models reflects its own particular concerns and priorities. For instance any single photograph may be viewed primarily as social or historical evidence.Investigated in relations to the intention of the photographer and the particular context of its making.Related to politics and ideology.Assessed through references to process and techniques.Considered in terms of aesthetics and traditions of representations in art.Discussed in relation to class race and gender.Analysed through reference to psychoanalysisDecoded as a semiotic text [21]In the case of this discourse the analysis will be performed as per assumption of the following discussion. According to Rudolf Arnheim an environmental image may be analyzed into three components: identity, structure and meaning. It is useful to abstract these for analysis, if it is remembered that in reality they always appear together. A workable image requires first the identification of an object, which implies its distinction from other objects, its recognition as a separate entity. This is called identity, not in the sense of equality with something else, but with the meaning of individuality or oneness. Second the image must include the spatial or pattern relation of the object to the observer and to the other objects. Finally, this object must have some meaning for the observer, whether practical or emotional. Meaning is also a relation but quite a different one from spatial or pattern relation. [22]Thus an image useful for making an exit to a meaning requires the recognition a distinct entity of its different elements, and its meaning as a hole. It should be kept in mind that these are not truly separable. The visual recognition of an entity is matted together with its meaning. It is possible, however, to analyze the element in terms of its identity of form and clarity of position, considered as if they were prior to its meaning. To begin with, the question of meaning in the city is a complicated one. Meaning, moreover, is not so easily influenced by physical manipulation of objects. If it is our purpose to explore a city and its widely diverse background, we may even be wise to concentrate on the physical clarity of the image and to allow meaning to develop with proper searching.

5. Exploring Time and Places

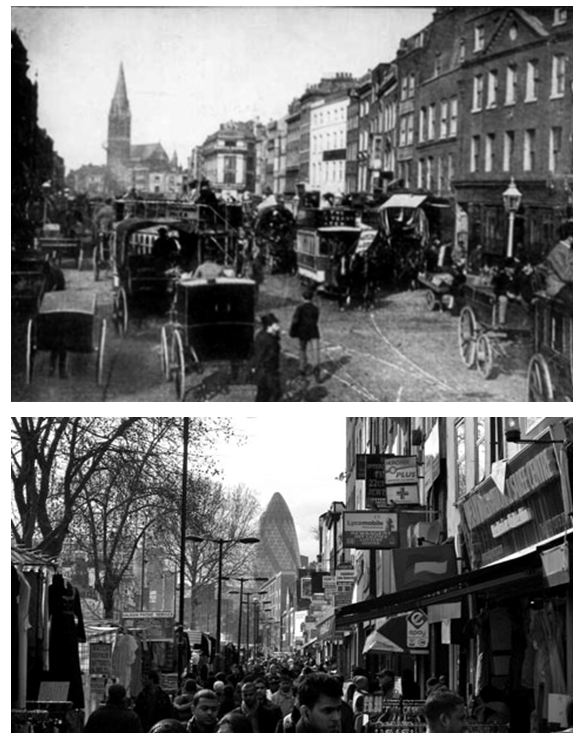

- To explore a city it is important to observe- ‘The contrast of old and new, the accumulated concentration of the most significant elements of the various periods gone by, even if they are only fragmentary reminders of them……………. The esthetical aim is to heighten contrast and complexity, to make visible the process of change’ [24]. So, the city itself can be a historical teaching device, an aim now served by the occasional guided tour or plaque.The temporal organization of memory uses external props: spatial clues, cause-and-effect relations, the memories and recitals of others, recurrent environmental events, or specialized devices such as records and calendars which can be derived through exploring city images. However, remembering a city depends on a context, whether internal or external. The environment in which a thing is learned becomes part of what was learned. Special mnemonic devices associate what is to be learned with vivid perceptual Images. In any case the city can be enormously informative, since the pattern of remains is a vast if jumbled historical.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML