-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2016; 6(2): 38-44

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20160602.02

Political Role of Urban Space Reflections on the Current and Future Scene in Cairo-Egypt

Dalia A. Taha

Architecture Engineering Department, October 6 University, Giza, Egypt

Correspondence to: Dalia A. Taha , Architecture Engineering Department, October 6 University, Giza, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In the aftermath of 25th January Revolution, Egypt examined a revolutionary situation with political and social mobility that aim to reform and rebuild modern Egypt. A call for Democratic Urban Space Design has been introduced and it is concerned with the users' rights, freedom of access, and freedom of action in public places in order to find a healthy interface between urban space, and politics. In this context, the paper highlights the need of urban designers in Egypt for a new and revolutionary conceptual thinking to: a) re-establish the relationship between man and place; b) re-reading the relationship between urban spaces and politics (in the shade of changing the concept of power); and c) expressing the ideas and goals of the revolution (especially with regard to the achievement of social justice), and accommodates the state of community audacity that explode after two revolutions. The objective of this paper is to propose a set of urban design guidelines based on democracy norms and highlight challenges that would face Egypt. In order to reach this objective, the paper will seek answers for the following questions: What are the aspects and factors that shape the relation between politics and urban space? What involves the formation of democratic urban spaces? What are the impacts of political events on the production and re-production of urban spaces? What are the appropriate urban design guidelines that represent the relation between politics and urban spaces? Are these guidelines appropriate and enough in the case of Egypt? Thus, the paper will first study the relationship between politics and urban spaces, highlights the impacts of political factors on the transformation s of urban spaces in Egypt, and provide a set of design guidelines that would enhance and accommodate the political role of urban spaces in the current situation in Egypt. The paper discussed the relationship between politics and urban spaces, highlighted the impacts of political factors on the transformations of urban spaces in Cairo-Egypt. How can we ensure that urban spaces are designed and preserved for democracy? Democratic urban spaces are not possible without a democratic process charged with shaping their character and form. Thus, the new interventions of urban design processes should be based on a comprehensive vision for development of urban spaces, together with consideration of all stakeholders views and a regulating framework for the development processes. The divergence of the interests between state and people can lead to contradictory plans and actions in the absence of a unified, comprehensive vision. The paper also discussed a set of urban design guidelines that would enhance and accommodate the political role of urban spaces in the current situation in Egypt. But, on the other hand, urban designers should recognize that good urban spaces are not designed but evolve over time. While careful urban design can enhance the quality of urban space, those spaces are also a result from a variety of social, economic, and political factors.

Keywords: Political Role of Space, Democratic Urban Spaces, Revitalization of Spaces

Cite this paper: Dalia A. Taha , Political Role of Urban Space Reflections on the Current and Future Scene in Cairo-Egypt, Architecture Research, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 38-44. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20160602.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The relationship between urban space and politics is both old and new, clear and complex. It is a subject that has been scarcely touched in the Arab World, generally, and in Egypt, in specific.Political theorists discuss urban spaces as a place of convergence between the people of a community, capable of containing their differences. It is a place of convergence of moral, which includes a set of common values allow people participate in collective deliberation, decision - making and action.Contemporary urban practices did not realize the real great value and vitality of the public spaces in most Arab and Egyptian cities. Urban public spaces are almost planned to not achieve the function of achieving communications between people. For very long time, governments are trying to keep people away from the public spaces, abort public life, drying channels that can accommodate sincere pulses of the community and convert those spaces only to be traffic corridors that almost devoid from public seats, [1]. It is always the question "to what degree can the political power allows demonstrations and protests to topple the power?". This conflict gave importance to the science and practices of "political urban planning", where democracy in urban spaces is recognized on the basis of the maximum limits that the city could allow to its residents politically. The recent political wave of change that sweeps across the Arab World highlights the need to re-understand the role of politics and how it will affect urban spaces' morphology. Hence, a need arises to re-read the transformations of urban spaces in Egypt as the base for future innovation; and reproduce spaces in the context of changing power from dictatorships to democracies, from more power to the ruler to more power to the people.

2. Impact of Political Factors on Urban Space Transformations in Cairo

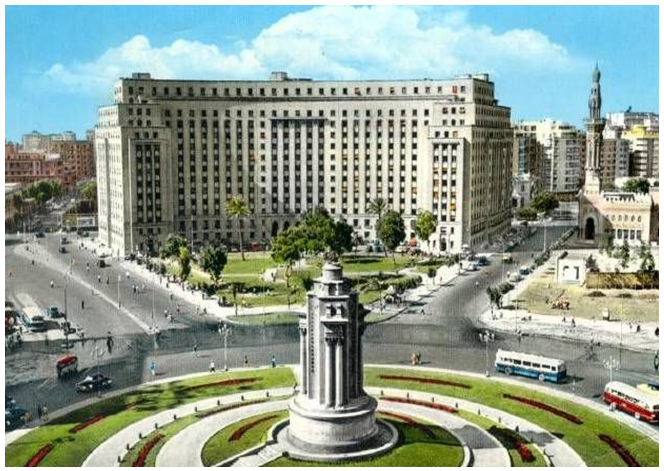

- Starting from the middle of the 19th century, A series of political, cultural, and economic transformations has taken place, which allowed for reshaping Cairo historical face and move towards modernization. Pasha Ismail (Khedive of Egypt from 1830-1895) had the vision to change the urban fabric of Cairo based on the model of Paris. Ismail decided to focus on the Western portion of the city by developing a new master plan (of a Polly Radial Pattern) to literally transform Cairo into the "Paris of the Nile", [2]. This led to loosing the identity of architecture and urban spaces, which became only an imitation of the Western model, and thus discontinuity between the extension of the city and its historic center. The urban development of Cairo downtown at that time had always been tied to the country’s political environment; the British occupation of Egypt and the influx of Europeans and foreigners had a significant impact on the architecture and urban spaces of downtown, Figure (1) (a,b).

| Figure 1(a). Urban Spaces in Kedivial Cairo at 30s |

| Figure 1(b). Architecture of Kedivial Cairo |

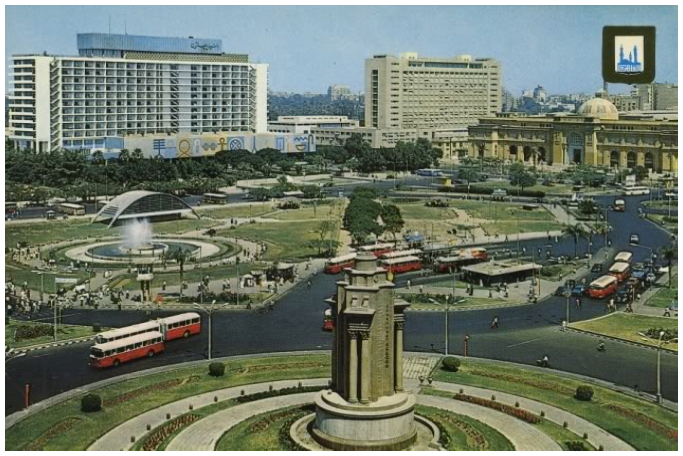

| Figure 2. Tahrir Square and Mogama building, an example of urban development that is based on state-owned buildings after the 1952 revolution |

| Figure 3(a). Tahrir Square in seventies |

| Figure 3(b). Tahrir Square before January Revolution, where it becomes a traffic corridor |

3. The Voice of People: 25th Jan. Revolution: From Virtual Space to Urban Space

- On January 25th, 2011, millions of Egyptians set to the streets demanding for ‘bread, liberty and social justice’. The 18-day sit-in in Tahrir Square or the "Midan" was crowned by the resignation of Mubarak, who had been in office for 30 years.The 2011 revolution in Egypt started in virtual public spaces, in a form of social networking sites, which played a vital role in the coordination and mobilization of activist groups. For those activists, the virtual space became to be the "last free space" to express their opinion, where everyone became a sender, receiver, and an active participant in decision making process. The January Revolution highlights again the physical relationship between man and place. Despite the power of social media in this revolution, nothing would be changed without the presence of an urban "real space" as the tool for pressure. Thus, the “virtual spaces” were not entirely separated from actual, physical ones, [5].The importance of Tahrir square comes from its proximity to the numerous governmental buildings and thus the occupation of Tahrir would provide a direct confrontation between protestors and symbols of the formal power of the state. Another important aspect in that space is the great visibility where congregation of the masses within a circular space would create an image of intensity and the advantages of remaining in the eye of international media, Figure (4).

| Figure 4. The circular shape of Tahrir Square gives an image of intensity |

| Figure 5. Occupation of London’s Trafalgar Square |

| Figure 6. Occupation of the Puerta del Sol in Madrid and the Plaça Catalunya in Barcelona |

4. The Republic of Al-Tahrir: A Redefinition of Urban Space

- During the revolution, Tahrir Square was gradually transformed into a city within the city. Within three days, camping areas, media rooms, medical facilities, gateways, stages, restrooms, food and beverages carts, newspaper booths, and art exhibits were established in the square, Figure (7).

| Figure 7. Post Revolution re-use of Tahrir Square-Street vendors selling National Flag and souvenirs |

5. From January 2011…to June 2013: Re-visiting Tahrir Square

- During the days of the Revolution, stencils and graffiti were the most common form of visual expression utilized by the protestors to express their identity, Figure (8).

| Figure 8. Graffiti in Tahrir Square |

| Figure 9. Upgrading Tahrir Square in 2015 |

6. Re: Politics, and Urban Spaces - A New Vision for Interface

- The role of the square during the events of the revolution verified that true public spaces within a city can be pivotal in securing social reforms and sharing information and perspectives that are essential to the formation of sound public social policy. The public square could foster civic participation in the democratic process by providing interactive platforms to encourage citizens to voice their views. The new vision for the relation between architecture, urban space, and politics is based on a shift from a political system that builds architecture to express its power, to architecture and urban spaces that produce and build the country's political system.Thus, a broader and more holistic concept of "Democratic" urban spaces is needed:- An urban space that is consider the relationships between various stakeholders and the impacts they have on the space.- An urban space that is achieve alliances between those stakeholders.- An urban space that answer a pivotal question of " Whose space is it?" not only to predict the future trends of different stakeholders in the urban space, but also to create a win-win situation between them.- An urban space that is designed to allow for a full experience of citizenship, and which is safe, clean, sustainable, and attractive. A key function of the urban development profession is to mediate between conflicting needs and between the competing claims placed on society’s natural, social, and economic resources. The questions are: How do urban design theory and practice articulate with the rights of democracy and citizenship in the urban spaces? How does urban design respond to the shifting conceptualization of political freedom and state-citizen relations? What can urban designers do to enhance the political role of urban spaces, especially in the shed of current situation where people need to voice their views.The answers of the above questions are three folds. First, on the policy level, there must be a comprehensive view to develop urban spaces that is consider and buy-in all stakeholders groups. Second, adopting the main criteria of the successful urban public space, which are defined by many researchers to be:1. Responsive: a public place should serve the needs of the community; provide the citizens with spaces that allow relaxation, discovery, and active and passive engagement.2. Democratic: Public spaces need to be accessible to all groups.3. Meaningful: People should be able to make connections between the place, their lives and the world.Third, on the urban design level, the paper argues the following factors are useful for both evaluating existing spaces and for designing new democratic ones:Size: The size would determine the number of people that can take part and participate in various political events and thus influence its success. It is therefore important to calculate the potential carrying capacity of urban spaces as in what is the maximum number of human beings that can occupy the space.Shape: The shape will determine how people perceive and experience the space. It also affects acoustics and visual contact, which people can establish within the space. Diversity: Democratic urban spaces demands a balanced and controlled mix of user groups and activities, where users from diverse backgrounds can coexist and practicing some similar activities without one group dominating another.Accessibility: The accessibility of a democratic urban space refers to all necessary elements (i.e. access ramps, sidewalks, audible and visual signs), which promote safe mobility. Participation& Modification: Refers to the engagement of the community (as possible) in the process of design and modification of urban spaces.Facilities for pedestrians: Refers to different aspects of comfort, urban ambience, and safety with respect to the physical characteristics such as the quality of pavement, slope, steps, street lighting, tree planting, barriers, and street architecture.Traffic Management: It is an important ingredient, which always used in all proposals for public space democracy. Considerable researches and literature have demonstrated that control of traffic speed contributes to one's attachment or detachment to public space. Traffic management also impacts the effectiveness of the use, access and participation in the space.Security: Is related to aspects of public safety and sense of protection, such as the existence of policing, and areas of "natural surveillance" that means areas with many people in movement and good visibility of the space.Comfort: An urban space needs to be comfortable in order to be democratic. This means adequate shading, seating space, sidewalks, and the presence of public transport with bus stops, routes and cycle lanes etc.Visual and Aesthetic Elements: Character of urban space influenced by certain elements including seating; hard and soft landscaping such as pavement, planting (natural factors); street furniture; shelter and protection (microclimate); subspaces; lighting, human scale and public art, [10].

7. The Case in Egypt

- There are some important points for discussion about public urban spaces for democratic discourse and political interaction in Egypt. Those points include:Hierarchical society: Egyptian society maintains a strong sense of the values of hierarchy and respect. This, however, created “communication barriers”, where open, free and frank discussion is an exception rather than a norm. Criticism tend to be taken personally, and people tend to consider having differing points of view as being disruptive to the sense of community. People generally shy away from open disagreement and are averse to giving feedback in a small society. Debate and in-depth discourse is yet to pick up. Constructive democratic discourse is limited under such circumstances, thus developing public urban space, wherein constructive and honest feedback can be shared is a complementary part to achieve democracy.Expectations of greater freedom and ensuing responsibilities: Democracy often comes with an expectation of greater freedom of speech and with expectations that citizens should become more active in taking on the responsibilities of holding the public sector and the government accountability. Technology gave people in Egypt more virtual space for sharing opinions, and media are providing more space for deliberation. People are becoming more aware of their roles and duties as citizens and their need to share views and opinions. Such reaction indicates the need to find channels and urban tools, where such voices could participate in constructive, responsive dialogue and participatory forums.Moreover, the Egyptian new democracy after the two revolutions has another challenge, where people rely on government to provide for and solve all problems including issues relating to governance. People have not yet realized that they are citizens with rights, duties and responsibilities. The capacity for claiming rights is often developed faster than for taking responsibility and performing duties. There is a need to encourage more sharing of responsibility to participate in the development of social and public policy through dialogue and deliberation.Therefore, in order to develop public urban spaces that are reflecting a healthy relation between urban design and politics (or in other words "Democratic Spaces"), the state, first, needs to develop a clear comprehensive vision for the development of this space. Then the successful implementation of a comprehensive urban development vision requires a democratic process that buy-in of all stakeholder groups when shaping the space character and form. Urban designers of public spaces needs to recognize that good urban spaces are not designed but rather evolve over time and they are a result from a variety of social, economic, and political forces.

8. Conclusions

- The 25th Jan revolution, which started in Tahrir square and continued in June 2013 highlighted the difference between how urban space is designed and how it is used. It was also obvious that the urban space has acquired a "new meaning" where the voice of people is an important element in the place design process.

Notes

- 1. The Egyptian Revolution of 1952 began on 23 July 1952, by the , and was initially aimed at establishing a republic.2. The Open Door Policy (Infitah) in Arabic language, was 's policy to open the door to private in Egypt in the years following the 1973 .

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML