-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2016; 6(1): 13-20

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20160601.02

Missing Costs and Benefits in Private Architectural Housing Projects

Saqer Mustafa Mahmood Sqour 1, 2

1Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, University of Al al-Bayt, Mafraq, Jordan

2Departments of Architecture and Interior Architecture, College of Engineering and Architecture, Al Yamamah University, Riyadh, KSA

Correspondence to: Saqer Mustafa Mahmood Sqour , Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, University of Al al-Bayt, Mafraq, Jordan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study deals with the missing costs and benefits in private housing projects. Clearly private projects concentrate on monetary costs and benefits; while social ones beyond that. Significance of the study comes from that private projects contribute enormously for the building industry; and these projects ignore social cost-benefit analysis. Thus, aim of this study is to identify these missing costs and benefits, and to propose suggestions for betterment. Methods used for conducting this study are: Reviewing literature about the (cooperative housing projects) of Jordanian Engineers Association (JEA), studying different opinions of different writers on the topic, choosing case studies from Jordanian Engineers Association projects, and identifying the missed costs and benefits in those case studies. The paper finds that cooperative housing projects aim to give out plots to members of their societies; they neglect other side effects. However, sacrifices are the social benefits or the values. The paper ends mentioning the importance of the social cost-benefit analysis, and the importance of government’s roles in private housing projects.

Keywords: Cooperative housing, Housing in Jordan, Private housing, Costs and Benefits in housing

Cite this paper: Saqer Mustafa Mahmood Sqour , Missing Costs and Benefits in Private Architectural Housing Projects, Architecture Research, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 13-20. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20160601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Occasionally, there are missing or hidden costs and benefits in housing projects. This remains supposed in all types of these projects; indeed private and cooperative housing projects are among them.The objectives of this paper are to discuss several these costs and benefits, taking in consideration their existence in cooperative and private projects.The main structure of the paper includes literature review. Further, the paper demonstrates the social costs and benefits through a detailed analysis of the cooperative housing schemes of the Jordanian Engineers Association.Besides, the paper highlighted appraisal, profitability, different types of costs, cost-benefit analysis, and feasibility report. It discussed sensitivity analysis, checking and evaluating projects throughout the paper and case study.

2. Literature Review

- There have been many studies and conferences on housing in Jordan. Further, there are fewer studies about housing projects in Jordan in the literature. But, researcher could not find studies on the missing social costs in cooperative housing projects in Jordan. Besides, there have been different studies on the topic in the eastern and western countries. Although the idea is different between cooperative housing projects and the housing projects introduced by the Jordanian Engineers Association, several of them could back this study. Some of these studies were used to enrich the text of this paper, while others form a basis to contribute extra understanding for the issue:

2.1. Studies in Jordan and Arab Countries

- Ÿ Ahmad Abu Al Haija, A study on strategies to solve housing problems; he suggested different methods to solve problems created because of slum areas. Further, he considered unplanned small housing schemes can form a starting point for slum areas [1]. However, this can be true in congested neighborhoods or crowded cities.Ÿ Atef Nusier, A Study on Housing policies between reality and expectations of the future. (2004) [2]. In his study, he proposed further motivation and all kinds of supports to the private and cooperative sectors for improved housing in the country. Which is significant for improving housing industry.Ÿ Different studies of Hala Jounat, Director of Housing Policies Department, Jordan. Among them A Study on Housing schemes as a supporter for sustainable cities, she discussed policies for setting up neighborhood; she urged cooperation between public and private and, and government interfere in all housing projects. Similar to what this study proposes further government authority on private housing projects. [3]Ÿ Studies of UN and World Bank, a Workshop on Analyzing Housing Sector in Iraq, (2006), the study highlighted the importance of partnership between private and public. [4]Ÿ Nasir Abu Anza, and Nusair A. (2007), a study on Jordanian experience in financing housing projects [5]. In their study they low income housing. They found it worthier to provide low income people with small plots. However, this is creating different problems as discussed by the author of this paper; because in this case, authorities are forced to go distantly from urban areas, due to high prices of lands.Ÿ Yousuf, M. M; from Egypt conducted a study on Role of private sector in achieving housing policies [6]. He discussed different periods and presented the Egyptian experience in financing housing projects. According to his study, Egyptian governments benefit from experiences of other counties like France, England and India. The policies of those countries are based on public plans and finance for substructure and basic services; next to leave the rest to individuals to do. Ÿ Proceedings of different conference, like:1. The Sixth Workshop on Evaluating Housing [7]. Housing and Urban Development Corporation, (2003), Jordan.2. The First conference on Housing, (2010), Kuwait [8].3. The Third Arabian Conference on Housing (2014) [9]. Different papers proposed applicable solutions for housing, Amman, Jordan.4. The region is expecting the Fourth Arabian Conference on Hosing; an influential conference to be held in November, 2016 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Studies in Other Countries

- Ÿ Cooperative Housing Federation of Canada & Rooftops Canada Foundation. A Study on Cooperative Housing in Canada: A Model for Empowered Communities [10]. The study mentioned that Canadian housing cooperatives gained a successful cost-effective management, self-governance, and carried public-private partnerships. This success can be traced directly to ordinary Canadians to own and manage their housing. Although economic circumstances and the roles of government may vary among the groups. Further, the study shows that of the cooperative experience can be used in other countries, to enable citizens to build and manage their own housing. Thus, this is a prominent start for Jordanians to start with.Ÿ The study declared that Housing cooperatives have proven that they have cheapest form of social housing, thus have proved that they are financially more sustainable than other forms. Besides, the study offers successful elements of Canadian cooperative housing experience that lends to broader application.Ÿ Institute for Research on Poverty University of Wisconsin–Madison, May (2010). Studies on Benefits and Costs in Housing Subsidy Program: A Framework and First-Year Estimates [11].Ÿ Michael P. J, Helen F. (2010). A Study on the Benefits and Costs of Residential Mobility Programs for the Poor [12]. The study aimed to present social improvements achieved by enabling low-income families to move from high to low-poverty neighborhoods. Such moves may improve schooling. The benefits to society from these changes remain notable when measured in money terms.Ÿ Chihiro Shimizu and com. (2005). A study on Search and Vacancy Costs in the Tokyo Housing Market: An attempt to measure social costs of imperfect information [13]. The study stresses housing social cost of imperfect information. The results suggest extensive social cost, if housing information were available.Ÿ Proceedings of the conference on World Habitat Day, UN Habitat (2011).

3. Case Study

- The case study of this paper is the housing projects of Jordanian Engineers Association (JEA). A national level projects spread all over the country. Further, main goal of this case study stood to achieve (a piece of land for each engineer). Process began in 1992 with four projects. The JEA started these projects in shape of plots with major services. Afterwards, when prices of land come to be higher, the committees were forced to propose housing schemes in the outskirts cities. The total number of the housing schemes achieved by this cooperative association is 158 projects, showing a remarkable contribution to housing in Jordan [14].In 2011 JEA started different types of housing [15]; they started constructing blocks that contain several flats in shape of apartment residences. This remained a result of high prices of properties.The JEA recognized Importance of providing engineers with houses or plots for houses. Therefore, they found out an independent department to handle hosing and property issues: The real estate department. It has three sections:1. Project s Department.2. Property and Information Department.3. Records and Regulation Department.Tasks and responsibilities carried out by the department:1. To buy plots.2. To sell and divide plots. 3. To prepare land use plans according to master plans.4. To implement infrastructure (roads, water, electricity) through tenders.5. To follow up, maintain and synchronize with various concerned departments and ministries.The housing project settled by the JEA can be considered a cooperative project. They are totally financed by the members of the society.Cooperative housing projects are private projects as they fulfill all basic needs of private projects, they can be reasonably analyzed and evaluated as an independent unit the basic needs for these projects are [16]. Electricity, water supply, earthwork, pavements of roads within each project and Sewerage lines. (If possible)Finance of these housing projects depends on customers who are members of the (JEA) cooperative society. They are from middle-income class, with countless limits in finance. In these projects, there exist two costs, namely: internal and external; The internal costs are the responsibility of users, who ought to suffer all of them [17]; these costs include building construction, footways, fees for building allows and pavement costs. The external costs of the project spell over users of other neighboring projects or over the society as an entity. Private housing projects are different from public projects; in public ones, economists and evaluators ignore finance because governments finance public projects, they increase money needed, earn loans, gain aid from different organizations or shift from the capital of one project to another. The methods of payment in (JEA) projects are:Ÿ Cash paymentŸ First advance payment.Ÿ Installment payment.Although these projects are for engineers, the decision cannot be considered a discrimination decision [18], since that these neighborhoods usually merge with the city, despite that they may influence neighboring areas.

3.1. Appraisal in Cooperative Housing

- Appraisal is a notable step in evaluating projects since that money is concerned. Here, the price of the land increases because of government taxes, inflation or changes in the value of money. If administrators do not consider these increases from the beginning, including the value of money with time, the project will face several problems in the future; one of these problems is the failure of the project (Figures: One and two). The responsibility of failure used to be thrown for the users who should pay more. Time value of money is essential in appraising projects; it depends on money has a time value [19]. Clearly one thousand Jordanian Dinar received now is worth more than one thousand Jordanian Dinar received in the coming years.

| Figure 1. Baidhat Alsalalim housing scheme [20], handed over to owners before 8 years [21], without any house constructed up till today |

| Figure 2. Unaibah, Jerash housing scheme [22], handed over to owners before 10 years [23] without any house constructed up till today |

3.2. Profitability

- Economists apply DCF for measuring profitability. Analysis here needs two types of consideration:Ÿ Payment made for plots and services, including capital and instalments.Ÿ Payments received for each year of the life of the project.All these values must be split into prices and quantities. And, here comes the importance of shadow prices and social cost-benefit analysis, which is missing in most private housing projects. Therefore, profitability itself is a private cost-benefit analysis.

4. Missing Costs and Benefits in JEA Projects

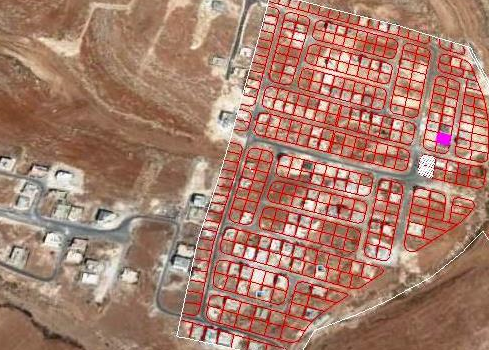

- The purpose of the private projects is to serve certain groups. It is, therefore, profitable in first-class. It focuses first on the concrete and direct profit for individuals. Therefore, the entire plot size exploitation largely noted (Figures: Three, four and five). This is done neglecting importance of public spaces, public services, parks, community centers, schools and commercial areas.

| Figure 3. Husban Housing Scheme, an entire plot size exploitation, without leaving space for public use [24] |

| Figure 4. Ain Ulbaida 2 housing scheme, an entire plot size exploitation, without leaving space for public use [25] |

| Figure 5. Um Hlelefah Housing Scheme, not even one plot for public services or uses [26] |

| Figure 6. Um Al Aqarib, a small-scale housing scheme within the urban context [27] |

4.1. Land Cost

- Cost of land remains the major cost considered by the people; the cost forced them to buy land that is little faraway from the city. Administrative committees used to buy the land based on prices, which means there stood no chance for any social cost-benefit analysis. (Figure: Seven)

| Figure 7. Nuqb Alsaegh housing scheme [30], Gave out in 2009 [31]. How long it will take to live in this housing scheme |

4.2. Construction and Services Costs

- The construction cost is the future responsibility of members; but, they are obliged to bear other costs before the end of construction; like road pavement, sewerage costs, electricity, water pipes and water tanks.

4.3. Maintenance Cost

- Maintenance cost does not exist at this stage since most of the buildings do not exist yet. Whereas, in the long run maintenance cost will include preservation of finishes and fittings of the houses, subsequently the buildings will continue to provide the same as they did when they first erected [32]. The maintenance costs are large as they contain many little items, such as servicing, cleaning, and replacement of parts. However, when pavement of roads takes place while construction starts after ten or twenty years, it means that roads are to be paved again. (Figure: Eight).

| Figure 8. Road pavements and some other services happen while no single house is constructed [34] |

4.4. Disturbance Costs

- Disturbance costs are the costs caused by changes while the maintenance is taking place. According to Stone, who wrote: The extra expenses incurred for covering plants would be charged as disturbance costs [33].

4.5. Operation Cost

- Private projects may need added costs; owners have to consider several principal costs, among them:Ÿ Plans and the way people impose them.Ÿ Management committees.Ÿ Distance, which affects the transport costs.

4.6. Social and Indirect Costs

- The most critical cost to consider in private projects is the social cost. It is essential to think of the comfort of users since they should walk a long-distance to find a public transport; after that to travel again to reach their place of work. (Figure: Nine)

| Figure 9. Al Hashmeiah Housing Scheme, faraway with no construction except road pavement [35] |

5. Social Cost-Benefit Analysis (Feasibility Report)

- There was no proper Feasibility Report in the case study of this paper; however, it remains the case of most of the private housing projects; these projects misses various characteristics of the social cost-benefit analysis. Some of these characters are:Ÿ It should detail the assumptions of the project.Ÿ It must point out accepted and rejected alternatives.Ÿ It must draw attention to special risks.Ÿ It must draw attention to the expected development of economy.Ÿ It should discuss management marketing.Ÿ It must show the financial needs overtime.The easiest and simplest form of analysis is to "put a social price on everything" [37]. Thus, estimators have to exploit shadow prices instead of market prices. Although some writers assume that only a short-run partial benefit cost analysis of housing mobility programs is possible [38].Social Benefit analysis is significant to encourage people to settle down in developed areas without planning to move to higher neighbourhoods. Otherwise, further programs needed to enable these people to improve the quality of their housing and to move to better neighbourhoods [39].On the contrary, new areas planned and established by the Government are designed properly and erected in time. (Figures: Ten, Eleven and Twelve)

| Figure 10. Design of king Abdullh Bin AbduAziz Housing scheme. [40] |

| Figure 11. Implementation of king Abdullh Bin Abdul Aziz Housing scheme [41] |

| Figure 12. Construction took place soon after approval of king Abdullh Bin AbduAziz Housing scheme |

5.1. Complications of Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Despite the fact there are several complications in this analysis, it is necessary for private projects. Although it has the following complications:Ÿ It has unquantified items.Ÿ It has to deal with an assumption on the Government policies.Ÿ Uncertainty is another chief complication; it considers whether the target of the project will live there or not, it may also deal with economy, inflation and currency rate.

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis in Private Projects

- The Second essential analysis for projects is the Sensitivity Analysis. It is an advanced stage that comes after the social analysis, however it must be done even if the latter does not exist.The sensitivity analysis shows how marginal the project is. It points out risks; therefore, it is a good way to deal with the unquantified values. Sensitivity analysis shows the margin of the project because the present social value of Jordanian Dinar 5000 does not show how small the project is; it might be a large balance between small costs and benefits; or a small balance between large costs and benefits.Sensitivity Analysis can be implemented by governments in shape of laws [42]. It is urgent since it is a proper method for dealing with unquantified items.

5.3. Shortcoming of Sensitivity Analysis in Private Projects

- Since this Analysis is the last stage of project appraisal, it may have specific shortages; these deficiencies may come from two sources:Ÿ If the evaluator uses it as an excuse for not quantifying different items.Ÿ If the project presents a set of switching values.Therefore, it is essential to quantify as much as possible from those unquantified items, even by the rules.

6. Monitoring JEA Housing Projects

- First criticism is about the absence of appraisal; no plans and decisions are taken at the spot. Therefore, checking remains difficult since that existing performance of the project does not mark strong facts. Therefore, it is difficult to measure the performance projects because it contains a collecting variables [43]. So, evaluators must divide the project in such a way that similar items are joined and checked separately.

6.1. Social Profits

- Social income stands as the value of the increase in supply less the value of increase in demand [44]. Social profits can be more or less common for both public and private projects; therefore, it is well to impose rules to evaluate uncommitted social income. The proper appraisal remains absent in the case study undertaken by this research; therefore, social benefit is negative; it may shift towards zero, or slowly towards the positive. However, some authors suggested that estimators must consider the use as a social income [45]. Since, the social income produced by the project is not the real measure of its yearly value to society.

6.2. Present Social Value (PSV)

- After knowing the yearly social profits, they can be put together to form a single measure for judging the project, which is done by counting social profits for every year. Thus, it is important to apply the rates of interest that is commonly applied elsewhere in the economy.If estimators could have a unique cost-benefit analysis for a private project, they could have easily known how to decide the proper interest rates. Means, they could know how the investment funds needed by the project that might have been used elsewhere. However, to explain this principle, two points are considered:Ÿ Future social profits must be counted in the same way in all similar projects. Ÿ A Thousand Jordanian Dinar in three years’ worth, now, less than that.If these two principles are applied in the cooperative housing projects, these projects will not face unavoidable problems in the future.In JEA projects the estimation for the development cost reached its total value before finishing 50% of the project. This happened in most of the projects as development happen after several years of starting and of paying the capital; which means that this project remained ill-conceived because of the absence of the feasibility report.

6.3. Labour Treatment

- Private housing projects are meant to provide members with a parcel of land as well as major services of the area: Water supply, electricity, sewerage and roads. These services need labour, which is to be treated well. Therefore, the following facts must be considered, some of them are:Ÿ To treat and pay labours according to their different jobs, occupations or posts.Ÿ To think about that high wage, occasionally, brings extra productivity.Ÿ To consider the increase in migration of rural labour to urban too.Several private projects have several social benefits, nevertheless they did not have social cost-benefit analysis to show that. In our case study the social profits are negative. Therefore, this paper recommends that many of these projects should have been shut down before starting.

7. Evaluating JEA Housing Projects

- Evaluating projects is part of monitoring. Further, evaluator must take in consideration the interests of neighbours, and the conflicts between the interests of individual developers and the community. However, it is essential to consider contribution of projects for development, and to realize that "development will only take place if it is for the individuals, firms and organizations wishing to develop [46]".

7.1. Methods for Evaluating the Project

- Evaluators must perform different calculations to be able to evaluate the private housing projects. Despite, it is not part of this study to move for such calculations, although architects can draw a procedure for them, this procedure follows the following steps:Ÿ Estimating the private profits.Ÿ Estimating public projects, in a way that how much benefit could public made by this housing project.Ÿ Estimating profits made for neighbours by the projects.Ÿ Estimating benefits made for the country.Ÿ Estimating the real rate if interests.Ÿ Estimating income, expenses, consumptions and savings.Ÿ Using accounting prices instead of market pricesŸ Estimating the social profits.Ÿ Computing the present social value.Ÿ Finally, authorities must perform projects if they are socially profitable; however if projects are not so, they have got to close them down from the beginning.

7.2. Differences between Evaluating Private and Public Projects

- The methods for cost-benefit analysis for cooperative schemes are similar to those of the public. They have two main differences related to the capital and profit.First: The Capital Opportunity: Opportunity cost of the capital in private projects is different from that of public; in public, governments invest money for public, if not for one project, they carry out for another one. But, in private or cooperative projects there are other possibilities in the capital:Ÿ Capital may be used for improper projects.Ÿ Capital may be invested in places which have the last priority in national or regional planning.Ÿ Capital may be kept without investment.Second: The Profits: The difference in profits can be summarized as follows:The profit in public results in extra consumption by increasing wages and salaries. But, profits in private projects encourage consumption among wealth, with profits fewer than extra consumption. Therefore, it is significant to conduct the social cost-benefit analysis for the private projects.

8. Conclusions

- In private housing projects, the project is owned by the members of the society. Members took responsibility of allotment of plots and development of site and services. In these housing projects, the market profits are guaranteed. It was sure that people will buy those pieces of land; thus, sacrifices remain the social benefits or the values.Usually, governments do not directly select the private projects, although they play a commanding role in doing so; they can favour these projects, including:Ÿ Limiting the area of land for cooperative societies in specific areas.Ÿ Tariffing materials and equipment.Ÿ Approvals, including decisions of the society to buy,Ÿ Approving the land use plans for the area.Therefore, governments must play its role to ensure the social profits for national advantages. They can perform that through licensing or financing authorities.Projects in developing countries, in general, and private housing projects in particular are different from those in the developed world; difference takes different shapes, such as:Ÿ Efficiency of time.Ÿ Importance given to the social benefit analysis.Ÿ Impact of the political reasons on projects.This paper highlights the importance of the social cost-benefit analysis in evaluating private housing projects since that such cooperative projects must have further social benefits than all other projects.There is a need that governments should have authority on private projects, to ensure getting the social benefits for every private project.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML