Abdelmajeed Rjoub

Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, al-Albayt University, al-Mafraq, Jordan

Correspondence to: Abdelmajeed Rjoub , Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, al-Albayt University, al-Mafraq, Jordan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

This Research concerned in studying the conditions of the emergence and development of Jordanian architecture and the extent of its communication with the architectural heritage resources of civilizations that have passed on Jordan. The main aim of research is to identify the heritage resources that Jordanian architects contacted with, and to classify the architectural styles and design relations which he used to achieve that communication. The author adopted descriptive and analytical methods to analyse the selected projects as models of contemporary architecture. The research found out that Jordanian architects preferred to communicate with Roman, Nabataea, Islamic and local heritage resources by expressing them at planning and architectural levels, and variations of design relationships. Research recommends increasing more attention to communicate with heritage because of its role in creating the original identity of Jordanian architecture.

Keywords:

Jordan architecture, Architectural heritage, Architectural identity, Architectural type

Cite this paper: Abdelmajeed Rjoub , The Relationship between Heritage Resources and Contemporary Architecture of Jordan, Architecture Research, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20160601.01.

Article Outline

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Research Objectives

- 3. Research Methodology

- 4. Literature Review

- 5. Historical Background of Jordanian Architecture

- 6. Case Studies and Analysis

- 6.1. Jordan's Parliament Building (Rasim Badran/ 1980)

- 6.2. Housing Complex for Cement Factory Workers (Rasim Badran / 1982)

- 6.3. Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Deeb Sha'sha'a, 1982)

- 6.4. Clock Tower (Unknown /1986, Removed)

- 6.5. King Abdullah I Gardens (Unknown, 1988)

- 6.6. King Abdullah the I Islamic Centre (Jan Cejka, 1989)

- 6.7. City Hall of the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) (Badran, and Toukan, 1997)

- 6.8. Jordan Islamic Bank Complex in Amman (al-Bitar, 1997)

- 6.9. Urban Planning and Landscaping of Ras al-Ain (Bilal Hamad, 1997)

- 6.10. Royal Hotel (Richard Martine, 2002)

- 6.11. al-Own Residence, (unknown, 2004)

- 6.12. King Hussein bin Talal Masjid (Khaled Azzam, 2004)

- 6.13. Islamic Gardens in King Hussein Public Park (Aiman Zoaiter, 2005)

- 6.14. Feynan Eco lodge (Ammar Khammash, 2005)

- 6.15. King Abdullah II Performing Arts Center (ZahaHAdid, 2007, not Implemented)

- 6.16. Jordan Museum building (Ja’farToukan, 2010)

- 6.17. al-Hamshari Masjid ( Atelier White, 2012)

- 7. Results

- 8. Conclusions

- 9. Recommendations

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Note

1. Introduction

Jordan in the last years of twentieth century has witnessed a comprehensive development which accompanied by expansion of urbanization in most of Jordanian cities and wide openness to global architectural trends, which made shifts in the Jordanian architect thought and contributed in re-formation of the Jordanian urban environment and the emergence of strange architectural styles and new types of buildings and neutralize the traditional architectural styles stemming from the rich and multi-cultural heritage of the region. This has led to the emergence of opposite reaction by some Jordanians architects who followed the application of ideas calling for return to cultural heritage and express it's elements in modern architectural projects, in order to preserve it and to be in touch with the past. They have a variety of attempts in the search for new architectural ideas and methods to find a genuine local features stemming from the cultural heritage of Jordan in order to create an identical styles for Jordanian architecture fit with the social and economic characteristics of the Jordanian community and Jordan's environmental conditions, without the application of strange theories and ideas, or configure not belonging forms and types to their heritage and their environment in spite of the intellectual and cultural challenges they face as a result of the effects of globalization and the policies of openness toward the West and as a result of the rapid developments in technology and multimedia. The idea of this research deals with the conditions of emergence of modern architecture in Jordan and its relation with the heritage resources of the civilizations that have passed in Jordan, and determine the extent of communication with heritage in contemporary architecture of Jordan, in order to identify the adopted by Jordanian architects levels and relations of this communication by studying and analysis of distinctive case studies of modern architectural projects for architects who they adopted that trend in Jordan.

2. Research Objectives

Research aims to the following:- Study the conditions of establishing and development of Jordanian architecture and identify its characteristics in general.- Study and analysis of selected models of contemporary architectural projects in Jordan during the period from 1980 until now in order to determine the extent of communication with heritage resources in the region and identify civilizations that belong to those resources.- Identify the levels of communication and design relations used by the Jordanian architects to achieve communication with the heritage resources deployed in the region.

3. Research Methodology

The researcher adopted the descriptive and analytical (inductive) methods to get the results of study by taking a sample of projects (case studies) which reflected the contemporary architecture in Jordan, and which their designers followed the trends of communication with local heritage resources, and applied the design concepts stemming from the use of planning and architectural elements of these resources within modern architectural styles and innovative design relationships. The selection of case studies took into consideration the clear formal and contextual influence of buildings by heritage resources and variety of their functions. In addition to the variation in the date of its implementation and their designers, the types selected projects also varied between the administrative, commercial, cultural, residential buildings, public squares, parks and others. The necessary data and information of selected projects has been collected by the following methods:- Going back to books, journals, websites and any references that containing any information about the selected projects to get to know their specific characteristics and design features. - Personal interviews with some of the designers of selected projects.- Architectural analysis and personal observation of researcher for drawings and images of projects and comparison with the original images of heritage resources that architects tried to express a communication with.

4. Literature Review

Researcher relied on previous studies that addressed the issues of heritage and local architectural identity in the Arab architecture in general and in the Jordanian architecture in particular, such as al-Faqih study about the reasons of going to the past and the role of heritage in the process of cultural and urban revival of Amman [1], and al-Bitar study were he discussed the concept of identity in architecture as a multi-aspect concept focusing into the role of human and social aspects on the formation of identity in Jordanian architecture in general [2]. Also researcher took into consideration the study of Rababe'h where he focused on the Nabataea architectural style and its impact as a cultural heritage resource on the built environment in Jordan [3], while the al-Arnaout study talking about the role of regional architectural trends in highlighting the concept of identity in the modern Arabic architecture through studying national experiments in Jordan during the period (1970-1995) [4], but al-Amery study concerned about the subject of heritage and the methods and techniques of its employment in modern Iraq's architecture. [5]

5. Historical Background of Jordanian Architecture

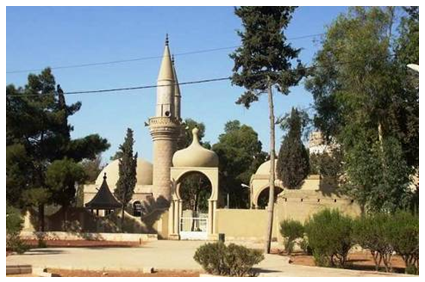

Jordan is an Arab kingdom in Western Asia, on the East Bank of the Jordan River. Jordan is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the south and east, Iraq to the North-East, Syria to the north, and Palestine to the west. Since the dawn of civilization, the country's location at the crossroads of the Middle East has served as a strategic nexus connecting Asia, Africa and Europe [6]. Archaeologists found evidence on inhabitancy dating as far back as the Palaeolithic period, later three kingdoms in Jordan emerged; Edom, Moab and Amon. The lands were later part of several empires; most notably Roman Empire, Nabataea Kingdom, all periods of Islamic including the Ottoman Empire which ended in the early 20th century [7]. These empires have left great heritage resources which consist of many important cities and architectural landmarks such as: temples, castles, Masjids, public squares and so (Figures 1, 2, 3). After the post–World War I division of West Asia by Britain and France, the Emirate of Transjordan was officially recognized by the Council of the League of Nations in 1922. In 1946, Jordan became an independent sovereign state officially known as The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. | Figure 1. The Oval Forum and ruins of Roman city Jarash. (Photo taken by author) |

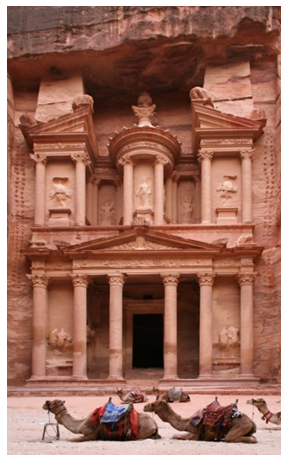

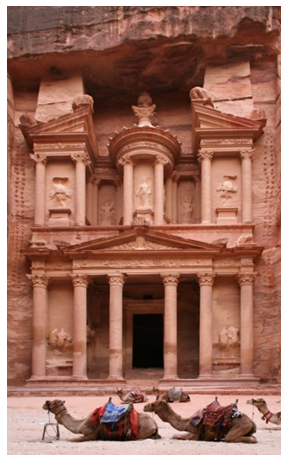

| Figure 2. al-Khazna in Petra of Nabataea. (source: ) |

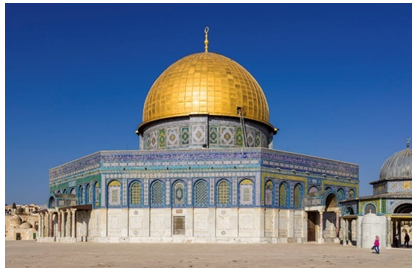

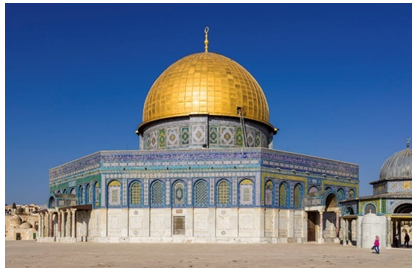

| Figure 3. The Dome of the Rock in the Old City of Jerusalem, the famous building of Islamic architecture in Jordan and Palestine. (Resource: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dome_of_the_Rock) |

After establishment of Jordan, Jordanian architecture passed through various stages. At twentieth of last century there were few buildings concentrated in the cities and villages, with vernacular styles taken from the Eastern Mediterranean countries. Buildings are rational in their plans and simple in forms and details, and small rooms overlooking to the open to the sky court (al-Housh) as a basic element in most of buildings [8]. Buildings were constructed by local builders (craftsmen) or Arabs who came from near countries (Syria and Palestine) or foreigners for there were no qualified Jordanian architects since this time [9]. They used available on the site building materials like mud, wood, rough stone and adopted traditional systems in construction [10]. Due to demographic migrations that have passed on Jordan since the beginning of its establishment until now, architecture has been affected by the mixing of the experiences of many new residents each according to the region from which they came. Also the Ottoman and English architectural styles had clear affect especially in public buildings and houses. The most famous buildings in that period was the Hijaz railway station buildings in Amman (1901), al-Husseiny Grand Masjid (1923), Raghadan palace (1927), al-Fateh Masjid (1933), in spite of a lot of individual houses in Amman, Irbid and Salt city [11]. (Figures. 4, 5, 6) | Figure 4. Hijazi Railway station's buildings in Amman (1901), as a Western architectural style. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

| Figure 5. Masjid al-Fath as a model of Ottoman architectural style in Jordan. (Resource: http://www.4r4b.com/vb/showthread.php?t=18854) |

| Figure 6. al-Murtadha residence in Amman (1923), reflects the architectural style of Eastern Mediterranean region.(Resource: [9]) |

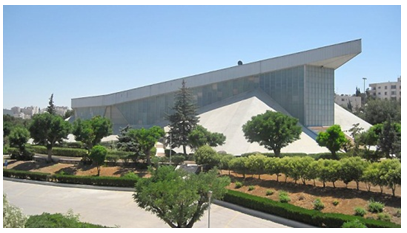

After independence modern architecture phase has begun as a result of changing in the social and economic conditions in Jordanian society, who took the Western model as a goal aspires to imitate and access it, this is came under the influence of elites, who have the power and received their education in Western countries, and have been affected by their culture as a result (al-Bitar, 1996). At this period the profession of architecture started to be more established and organized and it was entrusted to a group of qualified surveyors and draftsmen who were supervised and registered by the Department of Land and Surveying, and given a permit them to work practice as contractors or designer and they called later as (licensed practitioners)1, after that a group of Arab and Jordanian architects who finished their education in Arab or foreign countries entered the job market, so they were influenced by the international and modern architectural styles, and didn’t show clear architectural concepts in their new designs, but most of their production was affected by famous international architects and imitation of their buildings [10]. Buildings in that period characterized by the multiplicity of their functions and differing of types, and designed by several design concepts which mostly based on the principles of modern design principles and using wide range of new building materials such as concrete, marble, metal, glass and roof tiles with the use of original stone as a main material in wall facing. It could be argued that this period was an important transition period in which architecture in Jordan turned from being as a craft into organized and established profession. (Figures 7, 8, 9)  | Figure 7. The main elevation of Court of Justice building. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

| Figure 8. The Insurance company Building, the first tall building in Jordan. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

| Figure 9. The Cultural palace in Amman. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

Seventies of the last century witnessed vast changes in Jordanian architecture, and it can be considered a period of Renaissance of Jordanian architecture because of increasing the influence of international trends of architecture and ignoring the vernacular architectural styles as a result of the prevailing political conditions in that time and what was known as "Economic Boom" in the Gulf countries and being opening up to the Western world, and the increasing number of qualified architects who have completed their education in foreign countries. This has led to redirect the ABCs of architectural Jordanian discourse and made Jordanian architects to design new buildings using international styles but carried within them the attempts to find a distinctive features of architectural identity of Jordan, and the drafting of a local architectural language through communication with the architectural heritage resources of the civilizations that have passed in Jordan, mainly Arab-Islamic civilization. One of these architects was: Ja'far Toukan, Rasim Badran, Wadah Abidy and others. (Figures (10, 11) | Figure 10. Housing Bank complex building, as a model of modern architecture in Jordan in 80th of past century. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

| Figure 11. Samples of modern architectural style of individual houses (Villa) in Amman. (Resource: Photos taken by author) |

At the endings of the last century, a major development in architecture of Jordan was started because of the impact of intellectual and technological progress on the World and increasing the number of new graduated architects from Jordanian universities. Therefore, new building materials and advanced construction techniques have emerged, as well as the diversity of visions, cultures and intellectual concepts and methods of their application in architecture, which contributed in developing the formal and meaning sides of architecture. In this period, buildings which characterized as modern were varied by new types and forms, but they related to the heritage using various manners and method. That was the reason of sparking a considerable debate on the professional, educational and cultural levels of Jordan society about new concepts that have close relationship with the profession of architecture such as Identity, Privacy, Heritage, Authenticity, Modernity and so. This situation has led to formation two major trends of contemporary Jordanian architecture as follow:1. The first trend which called for openness to the World and keep pace with progress in the global contemporary architecture. The supporters of this trend tried to present their projects ideas as not linked to the local culture or/ and local environmental and social influences. In many cases of their projects they are turning towards their own understanding of the culture, expression their individuality or to show their affiliation toward a specific trend in international architecture.2. The second trend which called for a return to the past and discover the richness of the cultural and architectural values of local and regional architectural heritage resources., and take on consideration the heritage as a starting point towards renovation and modernity and as a mean in the search for the features of Jordan architectural identity and its distinctive types. Of Architects who supported this trend was Aiman Zoaiter, Nimr Bitar, Majid Tabba', Ammar Khammash recall and others who produced various projects in which they tried to apply such ideas.We can say that the general situation of Jordanian contemporary architecture is a combination of heterogeneous mixtures of cultural and social factors, political interferences and economic and demographic changes which reflects the mixtures of perceptions and visions of contemporary architects who lives in contradictory intellectual environment and influenced by distorted social and cultural values.

6. Case Studies and Analysis

In this part of study author present main information and analysis on selected (16) projects covering the period from 1980 to recent time. The author showed against each project the following data: project title, name of designer- if it's known, the date of implementation, explanation about the concept of design and how it was communicated with heritage resources.

6.1. Jordan's Parliament Building (Rasim Badran/ 1980)

It is a government building consists of a main hall where the meetings of the National Assembly held in addition to offices and administrative spaces belong to it. It is one of the first attempts to communicate directly with the Islamic architectural heritage in Jordan, Designer took Dome of the Rock building in Jerusalem as a reference as a concept of design due to its great importance to Muslims. This was reflected by the use of the octagonal shape in plan and repeated arches in elevations and the use of the dome in for roofing Council Chamber. Despite the fact that use of the dome element was monopolized only for the roofing in mosques, however, the buildings took the modern style for that time, especially its monumental facade and the use of new materials like hollow bricks and glass. (Figure 12) | Figure 12. Jordanian Parliament Building / the Council Chamber. (resource: Photo taken by author) |

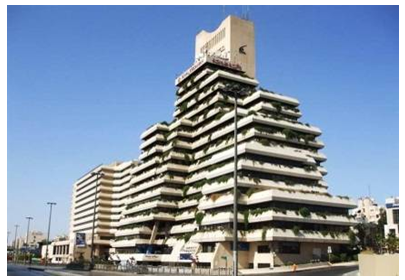

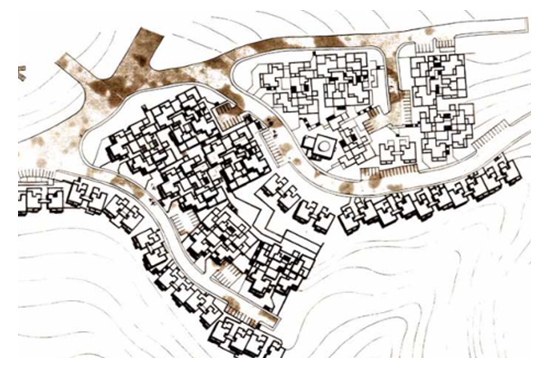

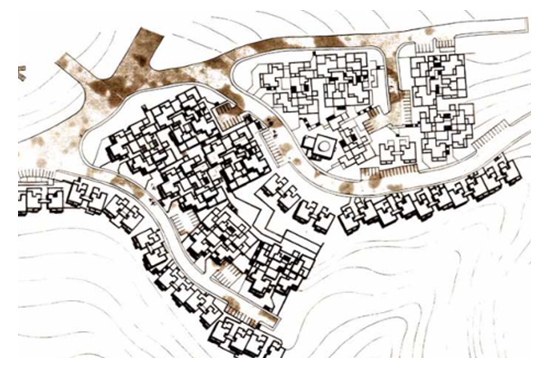

6.2. Housing Complex for Cement Factory Workers (Rasim Badran / 1982)

Housing complex includes (120) apartments with different types and areas, its considered one of the first experiments carried out in accordance with the modern ideas for massive housing in Jordan and supported on the concept of using the planning elements and formation of the traditional Arab city (James, 2005). Badran took the open court as a main planning element suggesting the theme of residential neighbourhood in the Arab city, where houses are distributed as integrated urban groups (neighbourhoods) but in modern vision at that time and taking into consideration the privacy for each house [12], and dealing with all site resources - physical and environmental- which contributed in formation traditional courts and balconies and providing all necessary services like markets, schools, and Masjid. (Figures 13, 14, 15) | Figure 13. Site plan of al-Fuheis housing complex for Cement Factory Workers (Resource: http://www.daralomran.com/arch/portfolio-items/cement-factory-housing/) |

| Figure 14. A part of houses of al-Fuheis housing complex for Cement Factory Workers (Resource: http://www.daralomran.com/arch/portfolio-items/cement-factory-housing/ |

| Figure 15. Panoramic view of al-Fuheis housing complex for Cement Factory Workers. (Resource: http://www.daralomran.com/arch/portfolio-items/cement-factory-housing/) |

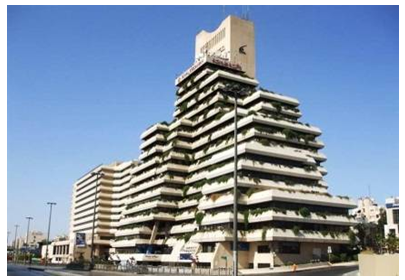

6.3. Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Deeb Sha'sha'a, 1982)

Administrative building consist of ten typical floors were architect attempt to show the Nabataea architecture by imitating elevation of "Khazna" in Petra with enlarging the scale and proportions of its architectural elements and giving it modern features and materials like natural shaped stone and glass surfaces on the main elevation (Figure 16). | Figure 16. Building of Ministry of Communication and Information Technology of Jordan in Amman |

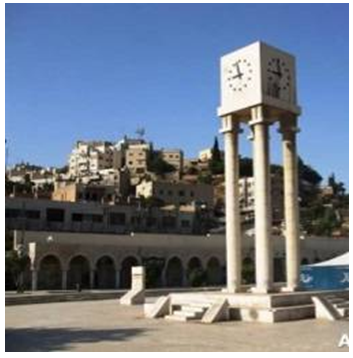

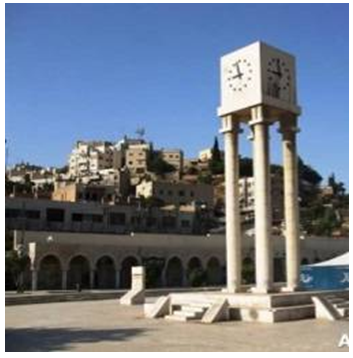

6.4. Clock Tower (Unknown /1986, Removed)

It's a monumental Clock tower located in the Hashemite square in Amman downtown. It consists of concrete cubic which sits on four pillars 15 m height, and a clock was installed on its four sides. The main concept behind the design of this project was to decorate the column abstractly in order to make inspiration with Roman style which seems in the remains of Hercules Temple in Amman Citadel facing the site of tower. The tower was removed after reorganisation works on the square. (Figure 17)  | Figure 17. The clock tower on the Hashemite Square, Amman (removed) |

6.5. King Abdullah I Gardens (Unknown, 1988)

Entertainment and commercial complex consists of amphitheatre, exhibition halls, markets and entertaining activities. What distinguish the site plan of this project are two intersecting axes, north- south (kardo) and east - west (Decumano) lead to amphitheatre and to the main Street. This reflected the approaches of planning in the Romanian city as well as the quotation of roman architectural elements like amphitheatre, squares and stone arches. (Figure 18). | Figure 18. Aerial view of King Abdullah I Gardens in Amman. (Resource: Google Earth) |

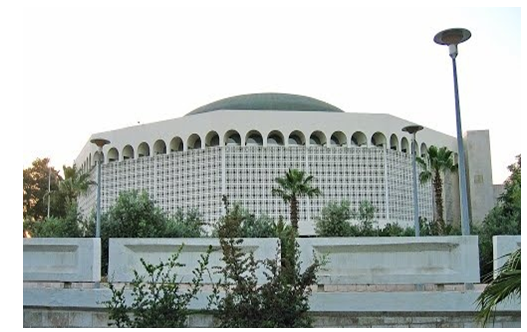

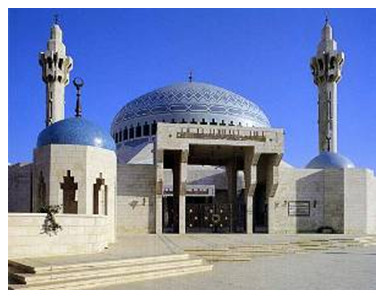

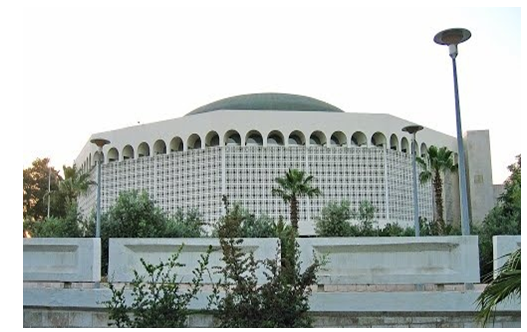

6.6. King Abdullah the I Islamic Centre (Jan Cejka, 1989)

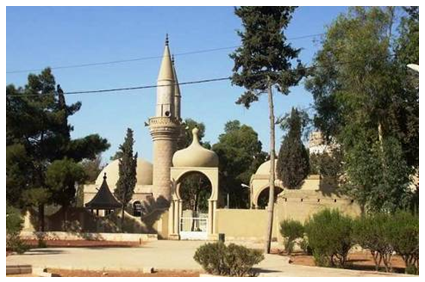

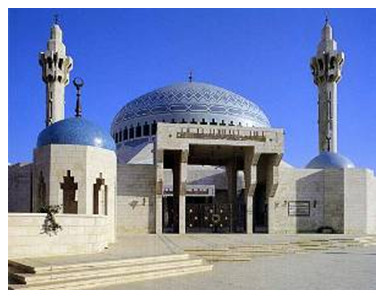

Located on the heart of Amman city in al-Abdali district, it has great importance for being the Grand Masjid and built in memory of king Abdullah the first. The complex contains a lot of spaces most important of them prayer hall which can accommodate up to 3000 prayers and the galleries surrounded it (Riwaq), women praying hall, Islamic museum and Imam Residence. Architect use regular octagonal layout in all parts of complex in order to continue with the Dome of the Rock, but in prayer hall the octagon transformed to hexadecimal dome which cover the whole hall to give another dimension in designing affected by monumental style of Ottoman masjid where one central dome roofed one space. In this project the designer has tried to find a contemporary Islamic architectural style by making an approach and combination between the different Islamic styles, so the design became mixed but in Jordanian pure flavour by using of traditional Jordanian stone in facades, mosaic instead of ceramic tiles and faience (Ali, 2013), and the use of Islamic motifs engraved on marble and Arabic calligraphy on the interior and exterior walls as a sign of Islamic Art and its aesthetic features. (Figure 19). | Figure 19. The main elevation of King Abdullah the I Islamic Centre. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

6.7. City Hall of the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) (Badran, and Toukan, 1997)

The city hall building houses the Mayor’s offices, municipal council chambers, meeting rooms, staff offices and an auditorium, while the ground level holds public spaces including a café, exhibition area and reception and surrounded by parks and public space. Designed in a pure square form, the centre circular court is transcended with a sundial; collaborating the roots of the past with the modern era. The mixing of more than one architectural styles- Roman, Islamic and traditional - although the effecting in architectural styles of Umayyad palaces was more noticeable (Hallabat and Mushatta). The architectural design is characterized with the elegance and tradition through the use of local natural stone and thick stone walls with neat graphics and forms that are eye catching. Also the massive pillars rundown in the external arenas was indirect reference to the last vestiges of civilizations on the land of Jordan. (Figure 20) | Figure 20. City Hall of the Greater Amman Municipality. (Resource: http://www.ccjo.com/en/jafar-toukan-projects) |

6.8. Jordan Islamic Bank Complex in Amman (al-Bitar, 1997)

Multi story commercial building located in Amman. The design of the building recalls the old traditions of ‘Wakala’ (agency) - the traditional prototype of a commercial mixed-use building in the Arab Islamic city. The central atrium in the middle of the building with full height and insulated glazed ceiling, with galleries all around and panoramic elevators and escalators revives the old notion of a communal commercial ‘Souq’. The exterior facades of the building exhibits many traditional details which were developed in a contemporary spirit using the white local stone and the pinkish stones with much efforts in carving and 3-dimentional treatments such as ‘Muqarnas’ and ‘Mashrabia’. The work included interior decoration with Islamic spirit for the public spaces of the building. (Figure 21) | Figure 21. The main elevation of Jordan Islamic Bank commercial Complex in Amman. (Resource: http://www.bitarconsultants.com/) |

6.9. Urban Planning and Landscaping of Ras al-Ain (Bilal Hamad, 1997)

A major site in the heart of the city of Amman was revealed, as a result of covering an abandoned stretch of the down town water stream (Al-Sail) with a box culvert. The site measures 1400m long *120m wide running along one of the main thoroughfare of Amman. It consist of administrative building of GAM, historical museum of Jordan, the cultural centre, parks and public squares. The most significant monument here is the fountain square which located at the end of the complex, it’s a circular shape plaza surrounded by colonnaded building which designed in modern style, and it’s an attempt to imitate the unique oval colonnaded Forum in Roman Jerash city. (Figure 22) | Figure 22. Aerial view of Ras al-Ain complex in Amman. (Resource: Google Earth) |

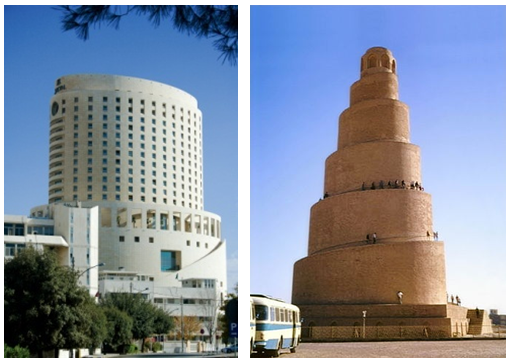

6.10. Royal Hotel (Richard Martine, 2002)

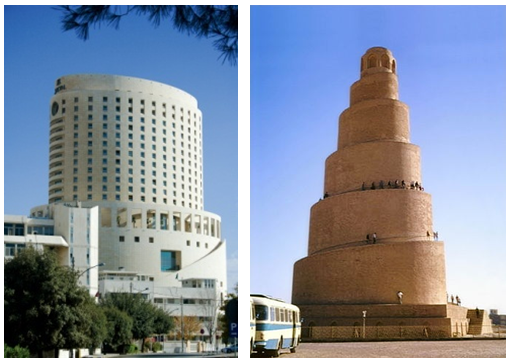

It’s one of distinguished monumental buildings in Amman as a tower of 108 m height. The project grew out of the idea of the Arab and Islamic architecture in particular the Tower of Babel and Helicobacter (Malwiya) in the city of Samarra in Iraq. This was clear because of Iraqi nationality of the owner who wanted building to be related to Iraqi heritage with mixing and creativity in design with modern construction methods. (Figure 23) | Figure 23. The Royal hotel building in Amman (right) and the Tower of Samarra (Malwiya) in Iraq (right) |

6.11. al-Own Residence, (unknown, 2004)

Country house located in the village of "Sabha" in Mafraq governorate consists of two floors, first floor consists of main entrance and guest hall, second: bed rooms, kitchen and toilets. Architect refers to front elevation of "Khazna" in Petra city to use it as monumental element of residences entrance but in miniature scales. He also used minimal architectural elements of Nabataea architecture to decorate windows and doors like Cornices and Friezes, as well as a combination of colored concrete and natural pinkie stone to express the distinctive original stones colour of Petra. (Figure 24) | Figure 24. The main elevation of al-Own residence. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

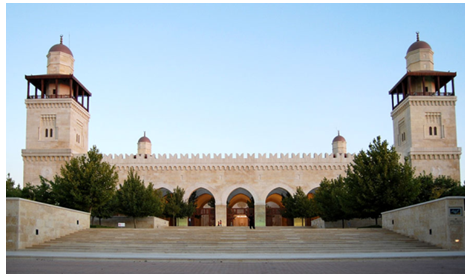

6.12. King Hussein bin Talal Masjid (Khaled Azzam, 2004)

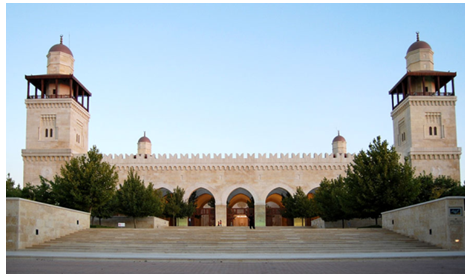

It's located in West Amman, where the new King Hussein public park is, it was inaugurated in 2004 to become an architectural landmark in Jordan. It is the largest (Grand) Masjid in Jordan and built to reflect the Islamic architecture prevalent in many historic sites in Jordan and around it (Bilad al-Sham). The four-minaret and one large dome masjid has a primary praying area which can accommodate 3,000worshippers and characterized by vaulted ceilings and Umayyad-style ornamentation carved in Jordanian stone. Meanwhile, a covered 2,000sq.m outdoor praying area with a similar 10 m high vaulted ceiling can accommodate 2,500 worshippers. All materials used for the building of the mosque are local, so Inside, is very serene with soothing colours with beautifully, finely constructed: floors, ceilings and arches. There is a women's prayer area above part of the indoor and outdoor halls, which can accommodate at least 350 worshipers. All the walls outside are covered with the classic white and brown stone that makes the mosque blend very well with the city. The Mihrab made of rare types of wood. The many chandeliers inside, carefully chosen and well placed - blend very well with the aesthetic beauty of the Masjid. Within, there is the Hashemite History Museum, which displays Islamic artefacts; and belongings related to Prophet Mohammed. [13] (Figure 25)  | Figure 25. The main elevation of King Hussein bin Talal Grand Masjid (Resource: http://www.khaledazzam.net/projects/king-hussein-mosque/) |

6.13. Islamic Gardens in King Hussein Public Park (Aiman Zoaiter, 2005)

This project is located in the centre of King Hussein Park, covering an area of 10000 m 2. It's a part of area of the Park known as Theme Gardens, where the main idea was to represent the various heritage and topographic areas of Jordan. The Islamic Garden designed by the Islamic Spanish theme utilizing the formal design of gardens and the usage of water elements (fountains and pools) decorated with elegant stone works, marble mosaics and soft landscape elements. (Figure 26) | Figure 26. View of Islamic gardens in King Hussein Park. (Resource: Photo taken by author) |

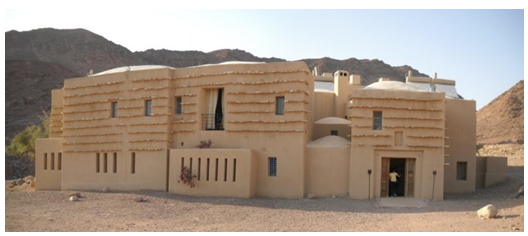

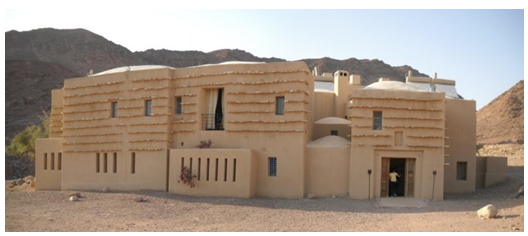

6.14. Feynan Eco lodge (Ammar Khammash, 2005)

Situated in the pristine Dana Biosphere Reserve is a first for ecotourism in Jordan. It's Owned by the Royal Society for Conservation of Nature (RSCN). Feynan Eco lodge integrates conservation and socio-economic development while promoting the importance of the natural environment. The lodge, 30 rooms, is designed according to studies of desert architecture in arid landscapes. It uses ecologically shaped architectural elements from traditional buildings in villages of Jordan. Deploying hybrid solutions based on the fusion of traditional materials and structural systems with contemporary building requirement and environmental design techniques, a balcony that surrounds and overlooks the lodge’s central courtyard leads to the individually designed guest rooms; each presenting a different view of rocky Wadi Feynan from a large window or private balcony. The usage of domes, vaults and mud skin all related to the local and traditional architectural style of buildings in the region. (Figure 27) | Figure 27. Front view of Feynan Eco lodge. (Resource: http://www.panoramio.com/photo_explorer#user =315243&with_photo_id=53099891&order=date_desc.) |

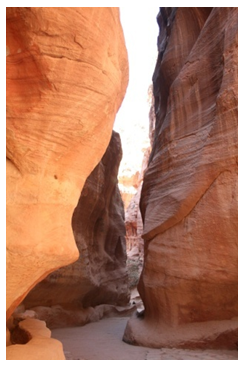

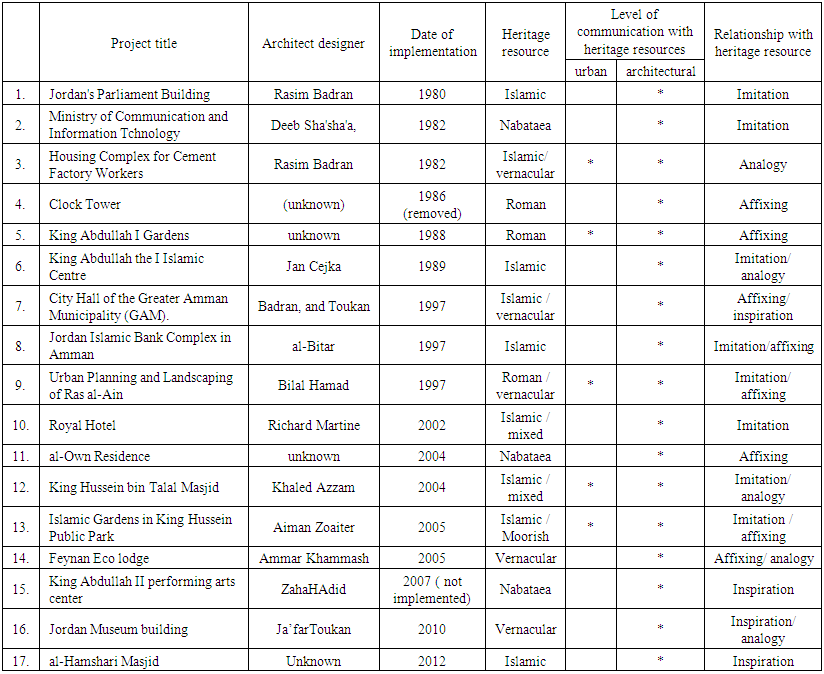

6.15. King Abdullah II Performing Arts Center (ZahaHAdid, 2007, not Implemented)

King Abdullah II for art and culture (used to be marketed as Darat King Abdullah II) is one example of the phenomenon of hiring internationally recognized architects, "starchitects" in Jordan. The project presented by Zaha Hadid won proposal the first prize in the international competition promoted by GAM, which includes a 1,600-seat concert theatre, 400-seat theatre, educational centre and galleries. The architectural expression for this project has been inspired by the uniquely beautiful feature of "al-Siq" in Petra where the rose-colored mountain walls have been eroded, carved and polished to reveal the astonishing strata of sedimentation. The designer have applied these principles to articulate the public spaces within the centre, with eroded interior surfaces that extend into the public plaza in front of the building. Hadid had brilliantly articulated the relationship and spatial flow between indoor and outdoor spaces. Moreover, she was very sensitive in providing outdoor space, probably inspired by the already existing Ras al-Ain strip across the street, which she invited to extend elegantly within the site. [14] (Figures 28, 29) | Figure 28. King Abdullah II performing arts center (not implemented) (left) http://www.zaha-hadid.com/architecture/king-abdullah-ii-house-of-culture-art/ |

| Figure 29. al-Siq- the canyon of Petra of Jordan. (Resource: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Al-Siq_(Petra)) |

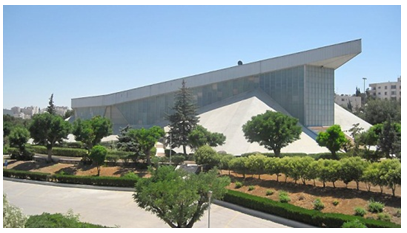

6.16. Jordan Museum building (Ja’farToukan, 2010)

The Jordan Museum is located in the dynamic new downtown area of Ras al-Ain. Presenting the history and cultural heritage of Jordan in a series of beautifully designed three galleries. The Jordan Museum serves as a comprehensive national centre for learning and knowledge that reflects Jordan’s history and culture, and presents in an engaging yet educational way the Kingdom’s historic, antique and heritage property as part of the ongoing story of Jordan’s past, present, and future. The chief architect of the museum building took the traditional style of construction in Jordan to express the concept of design. He has skilfully woven the concept of the building into its very fabric, with exterior materials suggesting the past and present (rough and smooth stones) and the future (glass). (Figure 30) | Figure 30. A part of front elevation of Jordan Museum building. (Resource: http://www.ccjo.com/en/jafar-toukan-projects) |

6.17. al-Hamshari Masjid ( Atelier White, 2012)

Implemented and sponsored by the architectural firm of al-Hamshari in 2012. It's located in Khalda District of Amman with total area of 21000 m2. The architectural style here embodied the new architectural approach of Islamic modern architecture which deals abstractly with the key elements of the mosque (Dome, Minaret, and Mihrab) to give them new forms and distinctive Architectural style, and gives a special concern to the local environmental conditions and modern construction systems. The Masjid's design is compatible with the environment, by relying on natural lighting and the use of modern insulation, which limits the use of energy to the ratios of up to 40%. Internal and external walls of the Masjid are decorated with Quranic verses and Islamic motifs. (Figure 31) | Figure 31. The Qibla wall al-Hamshari Masjid from the side street. (Resource: http://emadhani.blogspot.com/2012/08/2.html) |

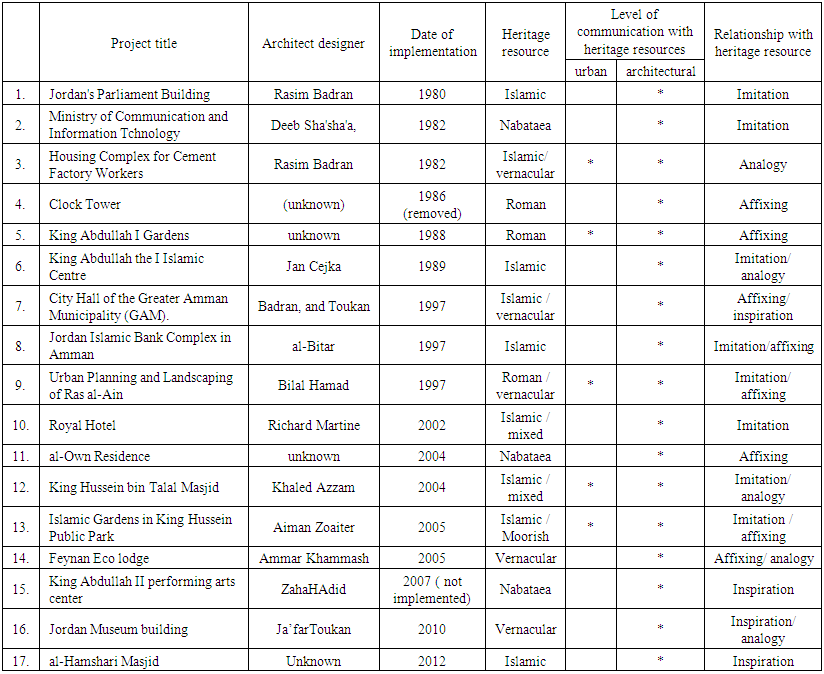

7. Results

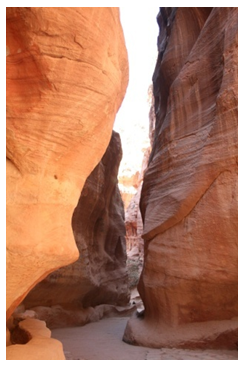

Reviewing the history of establishing the modern Jordanian architecture, phases of its intellectual formation and analysis of selected projects the author can conclude the following results:- There are a lot of Jordanian architects who interested in looking for roots and references of architecture in Jordan through going back to the past and inspiring with heritage resources of past civilizations. Jordanian architect could find different heritage resources in order to generate features of identity for modern Jordanian architecture as a reaction to ideas calling for Westernization in culture, effects of Globalization and international trend in architecture. They could find also more than one model to compose a different relationships to express communication with these heritage resources in new architectural projects.- The study showed that the main heritage resources which used by Jordanian architects to be as references for contemporary design ideas were as follows:Heritage of ancient civilizationsJordanian Architects paying attention to communicate with the architectural heritage resources of ancient civilizations, most notably Roman, Greek and Nabataea, which remains still exist until now in most cities and areas in Jordan and contain in there formations the concepts and approaches of their planning and a variety of architectural styles, in addition of the range of distinctive elements and architectural features like amphitheatres, temples, Forums, squares and so.Islamic civilizationThe heritage of Islamic architecture in all its periods and ages and with all its styles and shapes gained a lot of concerns from Jordanian architects. It was so out of being a source of pride to him and tangible evidence of the achievements of this great civilization, and in order to revive the Islamic architectural thought once again and strengthen the communication of Jordanian community with His history and authentic civilization. Those concerns emerged in the Jordanian contemporary architecture by highlighting the technical aspects of Islamic architecture, focusing on the aesthetic and educational values related to the social lives of people that formed original multi-functional Islamic urban tissue.Traditional (vernacular) architectural heritageJordanian architects directed towards the traditional architectural heritage resource to revive it in sophisticated modern ways in contemporary architecture. That is because of carrying different meanings, values and presenting appropriate architectural solutions to the contemporary issues of architecture n Jordan, either by using of local building materials or traditional structural systems which appropriate socially, economically and environmentally and the role that can be played in creating the features of the modern Jordanian architectural character being closer to human and in harmony with nature.- The study revealed that there is a clear disparity in methods of strengthening the relationships between the Jordanian heritage resources and the Jordanian contemporary architecture. This can be explained because of the divergence of visions and differences in point of views in general about the importance and depth of vision in the understanding of heritage from one side and what are the mechanisms and methods possible to communicate and how to deal with its resource from the other side.Communication levels- The study showed the presence of two types of levels pursued by the architects in communication with heritage resource in the contemporary architecture of Jordan:Planning level: Which mean that communication with heritage resources affected by the approaches and methods of planning of ancient cities using some heritage features and patterns in planning of new urban areas like parks, neighborhoods and trying to give it a renewal style or new functions for example.Architectural level: which mean that communication with the architectural heritage resource was through influence through being influenced in an architectural style of specific building or the use one of its architectural elements, as well as using the main building materials and construction systems, such as columns, arches, vaults and decoration elements and so on. There a lot of examples for this type of levels appear in context of research.Communication relationshipsThe results of analysis the selected projects verified four different types of relations that Jordanian architects used to confirm his communication with heritage resources as the following:- imitation: where architect copies one or more than one element from the heritage resource of certain civilisation period and paste it on the front of the new building, which gives the viewer a feeling that the building is old and trying to present it in a modernist style focusing on aesthetics and formal aspects using several building materials. We can see this technique obviously and mainly on the elevations of buildings with some modifications using principles of addition and repetition, or shifting in the scale and proportions of original heritage elements without consideration to the other architectural design aspects, functional for example, therefore this is a kind of architectural falsification and seems to act naive and devoid of any architectural creativity. - Affixing: This relation is used when the architect – to enhance the communication with Heritage – selects one or more than one traditional architectural element or style and trying to distribute it on the facades of modern buildings spontaneously with the hope of giving the heritage character to the modern building without paying attention to the final form of the building or its function.- Analogy: Architect here refers to the heritage using certain heritage elements on modern and sophisticated method of design to fit it with the new requirements or to solve specific design problems, whether its structural, environmental or any other problem. - Inspiration: which means taking the causes of heritage resource, its philosophy of design and its content into account and trying to reformulate it and use by new and innovative thoughts of design. Architect can reflect various design methods whether in spatial relationships or forms with some signs abstractly or indirectly to the architectural styles of heritage resources depending on his personal vision.The overall results of selected projects analysis are shown in the following table: | Table 1. The overall results of selected projects analysis |

8. Conclusions

Research confirms that Jordan is a country deep in history, diverse in civilizations and rich in architectural heritage resources. This heritage considered as a cultural wealth and we must preserve it and be in touch with it. It has to be examined to clarify its characteristics and benefits and complete the process of its development to become more convenient with the modern circumstances and variables of this age. This is because communication with the heritage connects successive generations with different cultural entities of society, and obtaining an authentic present full of values and noble meanings based on the solid roots and stable foundations derived from its past. The attempts of Jordanian architectural in communicating with Jordan's heritage are an important step to counter the dominance of the international architectural styles in various types of buildings in the Arab world and Jordan as well. The attempts of Jordanian architects to link the past with the present in their design through the employment of heritage resources in modern architecture also can help in the process of development and modernization of Jordanian architectural character and in discovering new architectural features to shape the local architectural identity fit with the social, economic and environmental conditions of Jordan.

9. Recommendations

At the end of research the author recommends the following:- Emphasizing the need for continuation the attempts of Jordanians architects to communication with the heritage of all civilization that passed in Jordan and all its components in the process of designing and production modern architecture, as this heritage is rich and diverse and it has an important role in linking the past with the present.- Emphasizing the Jordanians architects to create various design methods and modern architectural styles to express the communication with heritage and harnessing new technologies to meet the changing in needs and requirements of Jordan society.- Studying the cultural and architectural heritage resources of Jordan based on scientific and technological methods to know how they would deal with local environment and natural conditions as well as their architectural and formal characteristics in order to find distinctive and new styles of architecture that appropriate for the region.- Encouraging the specialized studies and researches in the fields of communication with the Jordanian heritage resources and adopting the methods of embedding their values and meanings in the educational and professional process of architecture.- Organizing conferences and specialized seminars which deal with the issues of communication with various types of architectural heritage resources.- Organizing architectural competitions which aimed to communicate with the heritage and encouraging the local and foreign architects to participate in and honouring the winners and participants.- Encouraging Jordanians architects on search and benefit from international and regional successful expertise and projects in the field of communication with the architectural heritage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was carried out BY dr. rjoub while on sabbatical leave from al-albayt for academic year (2014-2015).

Note

1. Jordan Engineers Association records indicate that 43 licensed practitioners was registered in architecture branch, were the most of them contractors and surveyors who educated out of Jordan.

References

| [1] | S. al-Faqih, 'Cultural and urban revival: Amman on transforming period'. Architectural Faculty Journal. Beirut Arab University, Vol. 8 pp 21-32, 1995. |

| [2] | B. al-Bitar, 'identity I architecture between reality and ideal: the case of contemporary architecture in Jordan'. M. Arch. Thesis, Jordan University. Amman, Jordan, 1996. |

| [3] | Sh. Rababe’h, 'Nabataean Architectural Identity and its Impact on Contemporary Architecture in Jordan'. Dirasat journal. Engineering Sciences, Jordan University, Vol. 37, pp. 27-53, 2010. |

| [4] | R. al-Arnaout, 'The role of regional trend in creating the concept of identity of contemporary Arab architecture: local experiences of Jordan 1970-1995'. M. Arch. Thesis, Jordan University. Amman, Jordan, 1996. |

| [5] | S. al-Ameri, 'The role of architectural heritage in reforming modern architecture of Iraq 1960-1990'. M. Arch. Thesis, Jordan University. Amman, Jordan, 1998. |

| [6] | http://www."History". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 2015-11-02. |

| [7] | http://www."Old Testament Kingdoms of Jordan". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 2015-11-02. |

| [8] | T. al-Refa'y, R. Kana'n, 'Iraq al-Amir and al-Bardon', Jordan University press, Amman, p. 5, 1990. |

| [9] | A. 'abu-Ghanimeh, Amman: Pioneers architects', Abhath al-Yarmouk Journal, Yarmouk University, Vol. 11, issue 1B, p 125, 2002. |

| [10] | A. 'abu-Ghanimeh, Amman memories of 50th', Article in the book: Studies in social history of Amman, Amman municipality press, Amman, p. 479, 2005. |

| [11] | T. al-Refa'y, R. Kana'n, 'The first houses of Amman', Jordan University press, Amman, 1987. |

| [12] | M. Matrouk, 'Unilaterism in Architectural Thinking and its Impact on Contemporary Trends: Experiences and Visions of Jordanian Architects', journal of King Abdulaziz University, environment design sciences, Vol 2, pp 87 -114 m, Riyadh, 2003. |

| [13] | http://www.khaledazzam.net/projects/king-hussein-mosque. Retrieved 2015-11-02. |

| [14] | O. Jarrar, 'Cultural Influences in Jordanian Architectural Practices: Post 1990'. PhD Thesis. Faculty of Environmental Design. University of Calgary, Alberta, 2013. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML