-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2015; 5(4): 107-112

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20150504.01

Regenerating Public Space: Urban Adaptive Reuse

Andreas Savvides

Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

Correspondence to: Andreas Savvides, Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper looks into frameworks which aim at furthering the discussion of the role of regenerative design practices in a city’s historic core utilizing the tool of urban design to jumpstart urban revitalization in the context of historic preservation and adaptive reuse in historic city centers. The main prong of investigation will consider the effect of proposed changes in the physical infrastructure and fabric of the city and the management of public space, as well as the catalytic effect of sustainable urban design practices. Through this process, the work hopes to integrate the contained potential within the existing historic city center, which includes both buildings and the space between buildings. It also looks at the notion of a community’s right to the public space and the public life of the target areas as well as the potential contribution and participation of its population in the local economy. It also examines ways in which this coupling of factors can bring to the front the positive effects of this combined effort on an otherwise sluggish local redevelopment effort, and uses a local case study to illustrate the potential application of preservation and reuse strategies in the historic core of the Nicosia suburb of Strovolos on the island of Cyprus. The data for this study is being collected and organized as part of an ongoing urban design and development workshop at the University of Cyprus. The presentation is organized around a historical background and theoretical framework for development, followed by concluding thoughts that address sets of actions that may have a positive impact on future projects conceived along similar lines by educators and practitioners in comparable regional initiatives.

Keywords: Urban Design, Public Space, Adaptive Reuse

Cite this paper: Andreas Savvides, Regenerating Public Space: Urban Adaptive Reuse, Architecture Research, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 107-112. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20150504.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

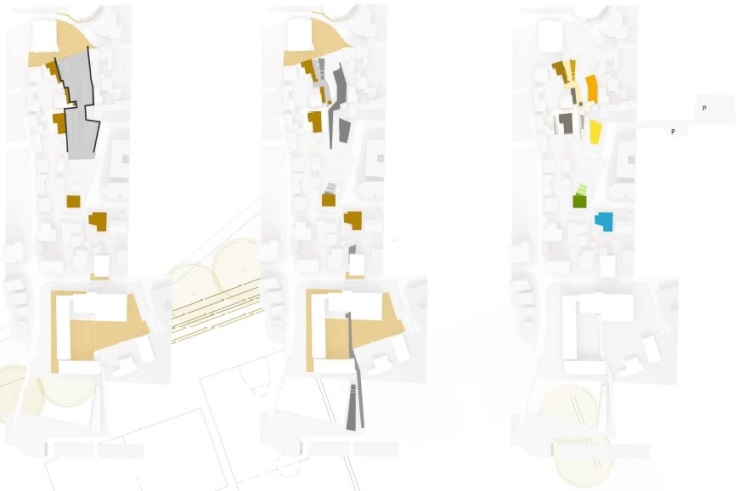

- European Union programs and international directives try to raise awareness of the need for an integrated approach towards the need for preservation of the historic parts of cities and the need for urban redevelopment and regeneration. These two aspects tie together the principles of sustainability with the principles of planning and urban design, which stretch from purist approaches that stress that the preservation of both natural and human resources is secondary to continued economic growth [1].There is a long history of interest in the conservation of the built environment [2]. It is a history shaped by both private concerns over the physical fabric of the city and public interventions to preserve the historic components of places [3, 4]. In relation to the public interest in the preservation of the built environment, early movements in the late 19th century sought to protect architecturally significant buildings and monuments while later efforts concentrated on the adoption of area-based measures concerned with the preservation of specific historically important places.This latter aspect became part of planning and housing legislation in many post war constituencies [4] and it is significant because it does not only deal with particular structures, but rather it takes into consideration the public space, which constitutes the surrounding context to these structures. It is a fact that in their own memories of times past and while growing up, many urban dwellers can draw pictures in their minds of familiar surroundings, often not of the buildings themselves, but of spaces adjacent to, beside, behind, in front of and even on top of buildings, in short, the spaces between buildings [5]. In most cases, the coupling of these two components that constitute the historic milieu seemed to be integrated and connected and not just space divorced from buildings. Instead, building components, such as stoops, porches, stairs, gates, patios and decks, were seen as items occupying the zone of public-private interaction between individual buildings and the public spaces related to them.According to Richard Sennett, though the importance of considering historic precedents has been established in the study and theory of urban form, much less attention has been paid to the historic precedents of urban functions or to the interplay between form and function. An example is the medieval town square. This was often the heart of the city, its outdoor living and meeting place, a site for markets and celebrations and the place where one went to hear the news, buy food, collect water, talk politics or watch the world go by [6].Such is the potential for the area around the location of the Panagia Chryseleousa Church in located in the historic core of the Nicosia suburb of Strovolos. Figure 1 constitutes an area plan of the site in question, while Figure 2 exhibits photographs from west to east and presents the site as it exists today, with marginal uses such as parking and unofficial storage serving nearby businesses and residences.

| Figure 2. The site as it exists with marginal uses, such as unofficial parking and storage |

2. The Right to Public Life at Strovolos’ Historic Core

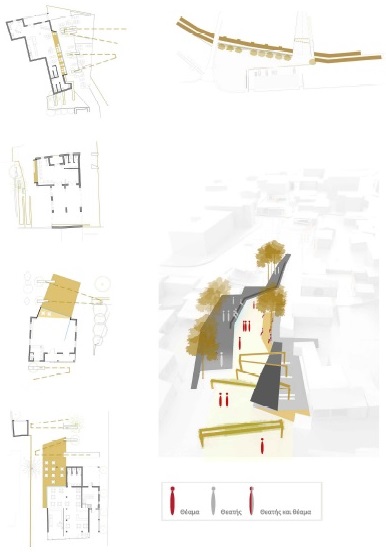

- The figures presented above outline the challenges and opportunities facing the municipal authorities and the local stakeholders who are involved in the preservation and adaptive reuse of the historic centre of Strovolos, a suburb located directly to the south of the capital city of Nicosia, in the Republic of Cyprus.Consequently the proposed analysis of the site in question focuses on the incorporation of cultural production related to an experience economy, as an injection of public life. It uses the tool of adaptive reuse to animate inactive edges and boundaries that characterize the site today. For this to occur, the surrounding area adjacent to the site has been analysed in order to tie the proposed corridor to existing routes that may be fed into the site, as indicated in Figure 3. Moreover, compatible architectural program is planned for the site so that it complements and enhances public life in the area, based on this new experience economy. Cultural venues and performance arts locales are proposed for the site in question, in the manner of an “open air theatre” affording stages for official and unofficial settings that serve planned and unplanned performances along the new thoroughfare.

| Figure 3. Existing thematic routes as they occur in the neighbourhood surrounding the site in question are noted and mapped and are then funnelled in the new proposed cultural corridor |

3. Approaches to Urban Adaptive Reuse

- In the case of the historic core of Strovolos, changes in the form of preservation, redevelopment and adaptive reuse are subject to patterns of restructuring that make their adoption, acceptance and impact – on the local discourse of development – contingent on a variety of factors, such as, firm closures, the relocation of capital, the need to attract new capital and the proliferation of the tourist economy, which may compromise the ability of historic cities to produce strategies that will regulate economic and physical growth within specified limits [12]. Moreover, any regulatory measures developed locally by the Strovolos municipality, aiming at creating a capacity framework, are likely to be effective only when complemented by measures formulated and implemented at multiple spatial scales.According to planning scholars such as Urry, it is possible to identify specific measures in which societies have approached the issue of historic preservation and adaptive reuse for urban regeneration. For the case of the proposed project at Strovolos this is expected to happen in four main ways: one is through stewardship of the designated historyic and listed building stock, another is based on the investigation of the propagated space, a third relies on visual consumption emanating from the theatrical nature of the proposal, while a fourth deals with issues of economic exploitation [13], especially as the proposal relates to the services and amenities provided by the more contemporary civic complex and municipal theatre. These conceptualizations of the relationship between community and the environment relate well to the often-hidden rationales for urban conservation [14].In the case of stewardship, the principle relies on the management of resources for the future of the historic core and it provides a strong justification for conservation.In the case of investigation of the propagated space, the spatial condition is portrayed as an object of investigation and in need of new programming, regulation and intervention, as in the case of land-use planning and its concerns over the need to develop sustainable development strategies both for the historic buildings and their related space.In the case of visual consumption the landscape or townscape is preserved and / or redeveloped not just for production, but also for its theatricality and its aesthetic appropriation [23]. Again, area conservation is important here because one of its rationales is the maintenance or recreation of a place's visual attributes. Areas are designated according to "the contribution of the townscape of buildings, streets and spaces” perceived holistically [6] as shown in Figure 4.

4. Cultural Forces Shaping Public Life

- Based on observations by Carr, one may identify the tree main cultural forces that will shape public life in the Strovolos proposal: The first is predominantly a social one, served by multipurpose spaces with various activities, but mainly focused on the social life of the community. The second is a functional form of public life serving the basic needs of a society – flows of people on the paths and streets, obtaining food for the household, providing shelter against the elements for themselves and for the collective. The third is symbolic public life, which develops out of the shared meaning people have for physical settings and rituals that occur in public. They are the spiritual and mystical experiences that occur in a society, the celebrations of past and memorable events that forge connections amongst people [17, 18]. By observing other people and their activities and participating with them in shared tasks in Strovolos’ historic core, the existence of a community can be perceived and made use of in the design proposal so that people feel that they may participate as part of a larger group in an active manner, as shown in Figure 5.

5. The Importance of Public Life

- The existence of some form of public life is a prerequisite to the development of public spaces. Although every society has some mixture of public and private settings, the emphasis given to each one and the values they express help to explain the differences across settings, across cultures and across times [17]. According to Carr, “The public spaces created by societies serve as a mirror of their public and private values as can be seen in the Greek agora, the Roman forum, the New England common and the contemporary plaza, such as the one proposed for Strovolos. When public life and public spaces are missing from a community, residents can become isolated from each other and less likely to offer mutual help and support.Commissioned studies in similar cases have been recommended to establish how near a particular city has come to reaching its limit of expansion and to discover the extent to which any potential growth (capacity for growth and the future pace, scale and pattern of development) may be made consonant with the maintenance of that city's historic fabric [20, 21], not unlike Strovolos’ historic core. In this case there exists a considerable scope for change and controlled growth in the target area without damaging those things that make it. More often than not, one has to balance the pressure for development, which can be harmful to the historic fabric if it is not carefully managed [14], against the withdrawal of investment, which could be equally damaging.

6. Conclusions

- For contemporary society, opportunities for public space and public life may be found in the old “urban villages” the historic nodes, such as the one in Strovolos, with their social support systems – as necessary a relief from crowded living and working environments as it is an essential setting for social exchange [22, 17]. In the process of choosing the spaces for their public lives, people in the community will be able to choose to experience other social groups in settings that are conducive to relaxed exchanges. Additional motives for making or remaking public spaces may also include issues of health, safety and welfare of the community, spatial restoration, environmental restoration and economic development.Public space can help define public “health, safety and welfare” by being a setting for physically and mentally rewarding activity, such as exercise, gardening or conversation. In public space people can learn to live together. The spatial and environmental restoration motives come into play in satisfying people’s needs for passive engagement, discovery and meaning. User participation helps the stakeholders understand fully the social context of a space, to strike the right balance among various claims on its use and meaning, to manage conflict and to adjust to changing public life over time [17].Despite local planning boards being entrepreneurial about effecting change, expressions of frustration over a lack of local control, increasingly lead to mobilization at the local and neighborhood level. As such initiatives occur, it can be expected that much of the interest will focus on improving the livability of local streets and neighborhoods and the shared public realm [8].In some cities, community activism helped convert abandoned or vacant lots into vest-pocket parks or neighborhood playgrounds. In some of the historic city cores in all major cities (including the ones in Cyprus), immigrant communities have brought street life back into the neighborhood [23, 24]. Members of these communities can respond to the changing demands of increasing diversity of the urban population [8], while recent immigrants (to Cyprus as well) have brought with them new shopping habits, leisure behavior, uses of informal economy and a new dependency on the public realm and they constitute now the major users of city parks. A new revival of street life is noted as well as an increasing popularity of flea markets, farmer’s markets and street markets. Lastly, there is also a general growth in the neighborhood-based grass-roots initiatives and nonprofit groups that are taking charge of community improvements – from affordable housing to small business development and open space design.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML