-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2015; 5(2): 67-87

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20150502.04

Italo-Australian Transnational Houses: Culture and Built Heritage as a Tool for Cultural Continuity

Raffaello Furlan 1, Laura Faggion 2

1College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, State of Qatar

2School of Urban and Environmental Planning, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan , College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, State of Qatar.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

(The Problem) The classical theorist Vitruvius celebrates architecture as an expression of societies’ cultural factors where culture has a determinant role in shaping built forms. Despite this notion of architecture has also been acknowledged by modern theorists, scholars stress that contemporary societies often ignore to consider buildings of cultural significance as an heritage asset of societies and therefore lack to protect them. (Objective) The purpose of this paper is to understand how the fulfillment of users’ needs, based on their cultural framework, had priority in the architectural design process of their houses. More specifically, the main objectives are (1) to understand the nature of the cultural factors influencing the form of Italian migrants’ transnational houses in Australia and (2) to recognize why these houses can be categorized as an heritage asset of the Australian built environment. (Methods) In order to provide an answer to the two research questions, firstly the authors review the literature supporting the significance of built and culture heritage within the development of the built environment; secondly a detailed case study in Brisbane is selected for the collection of data. (Contribution) As a result of this investigation, (1) the extent to which Italian transnational houses were conceived in response to specific cultural needs and (2) why these buildings, which are part of the multi-cultural built environment of Australia, should be preserved and restored, is revealed.

Keywords: Culture, Cultural heritage, Built heritage, Cultural traditions, Social capital, Vernacular and transnational houses

Cite this paper: Raffaello Furlan , Laura Faggion , Italo-Australian Transnational Houses: Culture and Built Heritage as a Tool for Cultural Continuity, Architecture Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 67-87. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20150502.04.

Article Outline

1. Background: History, Built Heritage and Culture

- The specific aim of the research study is to use the insights of cultural studies to investigate how cultural factors are embedded in the form of a specific typology of dwelling, the archetypal ‘self-built house (not renovated, refurbished or extended) on a quarter-acre block’, constructed in the post-WWII Brisbane by first generation Italian migrants. While the primary focus is upon the cultural factors influencing the physical form of dwellings, attention will also be given to understanding why this typology can be categorized as cultural heritage of the Australian built environment.This paper aims at revealing or finding convincing arguments for safeguarding cultural heritage in Australia with the purpose to stimulate actions of public actors towards the preservation and conservation of Italian migrants houses. The following paper focuses on an important aspect of cultural heritage that is, its role in the preservation of built forms within the built environment.The central research questions, then, are: (1) In what ways did post WWII first generation Italian migrants influence the form of their houses built on a quarter-acre block’ or ‘single front block’ in Brisbane, and what were the forces behind, and outcomes of, this influence; and (2) why these houses should be considered a cultural built heritage asset of the Australian built environment.The key objectives of this study are: to provide insight into the ways in which migrants influence the material environments of the Australian society; to explore a historically significant process of Australian domestic architectural development and therefore contribute to knowledge of contemporary Australian built heritage; to preserve and protect the various cultural factors preserved/embedded in the built environment which represent the national cultural heritage of Australia.

1.1. Culture and Cultural Material

- Culture is a broad and abstract concept defined by Emily Dickinson (Cited in Johnson, 1960) as the sharing by a group, or more broadly a society, of a common system of standards, meanings, language, manners of relating and interacting, behavior or way of life based on common history and tradition. Hall, Howard and McKim also stress that the knowledge of a culture is acquired by a sharing process of a cultural frame which a social group has in common (Hall, 1966, p. 172; Howard & McKim, 1983, p. 6). Besides, as stressed by Marcus (1995, p. 94), ‘a cultural frame refers to an interpretive grid, meaning system or schema. It consists of language and a set of tacit social understandings, as well as of the social practices that reflect and enact these understandings in daily life’. The concept of ‘culture’ and ‘cultural frame’ explained above provide a useful basis for understanding how people make sense of the world by sharing commonalities, such as language, behavior and more generally a way of life. The knowledge of a culture is acquired via a complex process. The sharing of culture comes through interaction, and conventional interaction is made possible when people have values and attitudes in common (Hall, 1966, p. 172; Howard & McKim, 1983, p. 6). The literature revealed that scholars and researchers point out that culture is conceptualized as existing in both cognitive and physical dimensions. (1) Rapoport suggests that environmental influences affect the way people think, behave and act, and that this can be detected in the spatial and constructed arrangements of their milieu: physical and cognitive behavior have a cultural framework. In his words: ‘Culture is ultimately translated into form through what people do as a result of what is in their heads and within the constraints of their situation’ (2000, p. 162). (2) Harris (1984, p. 32) stresses that ‘Culture encapsulates a person’s way of life and everything one thinks and feels, and how one behaves or represents thoughts/feelings in a social and spatial environment’. The view of culture extends to the way in which a social group represents itself through a spatial environment or its physical artifacts. This material aspect of culture is reproduced through mechanisms that are also part of culture; the design and construction of buildings, its characteristics, mirror the commonalities of a culture as a whole, or it distinguishes one built environment from another, as per the nature of rules embedded in them. Built forms differ from one culture to another (2005, pp. 18-57) (Gamble, 2001, p. 101).

1.2. Human Behavior and/or Activities as Expression of Culture

- Rapoport highlights that the relationship between culture and physical environments can also be expressed in response to human behavior. He points out the importance of exploring and ‘understanding patterns of behavior which is essential to the understanding of built form, since built form is the physical embodiment of these patterns. Forms, once built, affect behavior and way of life’ (Rapoport, 1969, p. 16). Also, Howard and McKim conceptualize culture as ‘the customary manner in which human groups learn to organize their behavior and thoughts in relation to their environment’ (1983, p. 5). This perspective suggests that cultural patterns or commonalities are manifested in spatial behavior through the creation of spatial environment, and finally that spatial environments are designed to encompass human behavior. Additionally, Rapoport (2000, p. 162) states that human activities are direct expressions of culture as a way of life. This is also supported by Inglis, who states that ‘Culture is the result primarily of human activities, rather than wholly the product of ‘nature’ (2005, p. 10). What this suggests is that human behavior, activities and spatial environment are joined by a cultural frame.Hence, the point of this current study is to explore the extent to which Italian migrants have modified the form of their houses, expressed through their architectural and spatial form as well the configuration and uses of the yards, in the light of the cultural frame that formed them. Therefore, the insights from Rapoport, Howard and McKim, highlighting the relationship between built form and human behavior and/or activities, as expression of culture and way of life, help (1) to understand the role of human behavior and/or activities as a determinant factor in the shape of a spatial environment (2) and to construct a conceptual framework for the exploration of the way Italian migrants influenced the form of their houses.Furthermore, Rapoport (Rapoport, 1969, 1982a, 1982b, 1997, 2000) highlights the importance and the need to dismantle the concept of activities into its variables. Rapoport identifies six components, which, in his theories, represent the system of activities. He highlights the variability of the activity which involves (1) the nature of the activity itself (what), (2) the persons involved or excluded (who), (3) the place where it is performed (where), (4) the order or sequence it occurs (when), (5) the association to other activities (how - including or excluding whom), and finally (6) the meaning of the activity (why). He stresses the importance of studying the systems of activities, because in his words ‘variability with lifestyle and ultimately culture goes up as one moves from the activity itself, through ways of carrying it out, the system of which it is part, and its meanings’ (Kent, 1990, p. 11).The insights discussed above suggest that an analysis of behavioral patterns and/or the system of activities, which are expression of culture, can help to understand the way Italian migrants distributed and utilized the domestic space of their houses.

1.3. Cultural Traditions

- Rapoport and Oliver argue that history has shown how building forms cannot be understood merely by reference to climatic conditions, availability of materials, technology and biological needs. Critically, in their view materials and construction techniques can facilitate and make possible certain decisions about the form but they cannot determine or provide fully an explanation of the nature and diversity of the form to be built; it is the subtle influence of cultural forces that may affect the way people behave, and consequently the houses and settlements in which users live and the way users use them (Oliver, 2006, p. 143; 1969, p. 85; 1982a). They conclude that physical factors are treated as modifying factors rather than determinants of the form, because they do not decide what has to be built, the ways and the reasons. In their view it is the cultural concept of the house, shaped by an accepted way of doing things, or traditions, which act as a factor determining the form. Once the identity and character of a culture has been grasped, and some insight gained into its values, its choices among possible dwelling responses to both physical and cultural variables become clearer. The specific characteristic of a culture-the accepted way of doing things, the socially unacceptable ways and the implicit ideals-need to be considered since they affect housing and settlement form (Rapoport, 1969, pp. 46-47). The relation between the form of vernacular houses and tradition is also emphasized by Oliver who stresses that vernacular architecture is usually developed where there is a strong tradition and a supportive environment (Oliver, 1997). Tradition and transmission consider the means by which traditions in vernacular architecture are passed on, or ‘handed down’ from one generation to another. Some of these are verbal, others require the training of bodily memory, but all are subject to the values and norms of the culture (Oliver, 1997, p. 70). Traditionally, the sensitivity and the know-how, the skills and the competence to build affectively in response the land, the climate and the resources to land, have been passed on between generations (Oliver, 2007, p. 16). In relation to this study’s it is essential to explore the extent to which the form of houses built by Italian migrants were influenced by (1) traditions, as an expression culture, as an accepted way of doing things.

1.4. Cultural and Built Heritage: The Connection between Past and Future

- Researchers state that cultural heritage, which surrounds us and enriches our spiritual wellbeing, is an expression of the culture as ways of life developed in the past by a community and transmitted on from generation to generation: it is a memory of our past and a vision for our future (Lusiani & Zan, 2013). Cultural heritage can be expressed as either Intangible or Tangible. Cultural heritage includes intangible heritage, such as beliefs, traditions, practices, values, stories, memories, oral histories, artistic expression, language and other aspects of human activity (Murzyn-Kupisz, 2013). Tangible (or material) heritage is made up of monumental remains of cultures, individual and groups of buildings at a different scale, objects and/or collections of objects. Specifically, it is defined as the qualities and attributes possessed by places and objects that have socio-cultural values and meanings or an expressly historical, archaeological, artistic, scientific, social or technical importance for past, present or future generations. Commonly, the significance for both tangible and intangible cultural heritage can augment because of its originality or unique connection between a group of people and of the extent to which it serves as surviving evidence of a society, within a certain period of time (Amit-Cohen, 2005).

1.5. Urban Development and Cultural Heritage Protection: Cultural Meanings and Built Form

- Researchers reveal that world heritage properties are mainly being threatened by two factors: aggressive development based on speculation, absence and/or inefficiency of management strategies and policies. The biggest challenge for the management of built heritage is to provide continuity and compatibility, as the urban setting keeps changing in form and function (Khalaf, 2015). Commonly the discussion on policy making about culture and heritage focuses on monuments protection and grand-scale buildings, neglecting other spheres such as housing. This context should be taken into consideration by practitioners in order to formulate more effective strategies within the field of heritage management.Scholars highlight that heritage plays a decisive role to locate a social group in its historical, social and cultural environment and that heritage protection contributes to social cohesion at the local community. Its uniformity fosters a sense of own identity, while its diversity encourages tolerance and respect for others (Nour, 2015). In addition, cultural heritage advocates sustainable development and cultural tourism in modern societies. Cultural heritage is interpreted as going beyond the preservation of singular buildings and/or artifacts: it acts at an interdisciplinary level by embracing multi-faceted disciplines such as archaeology, architecture, ethnology, landscape architecture, urban design and planning, art history and general history. The purpose is to wide the view, investigate and protect larger spatial units where wider values and/or diversity of cultural meanings are embedded in the built environment (Khan, 2015).Cultural heritage comprises the sources and evidence of human history and culture regardless of origin, development and level of preservation (tangible/material heritage), and the cultural assets associated with this (intangible/nonmaterial heritage). Because of their cultural, scientific and general human values, it is in the state’s interest to protect and preserve cultural heritage. The basic cultural function of cultural heritage is its direct incorporation into space and active life within it, chiefly in the area of education, the transfer of knowledge and experience from past periods of history, and the strengthening of national originality and cultural authenticity.

2. Research Methodology

- The relationship between built form and culture, expressed through (1) cultural traditions and (2) socio/cultural behavior and/or activities, has been reviewed, in order to establish the transmission of culture through built form. This section highlights the crucial role of selecting a methodology for this study. The choice of research methodology, strategies and methods that characterize the empirical part of this investigation is based on a number of theoretical and philosophical principles. The design strategy and the qualitative research methods utilized to gather the data are here presented.

2.1. Qualitative Research

- This study draws upon the work of Clapman (2005), who argues that quantitative research is not the most appropriate criteria with which to understand the cultural influences on the form of the house by its occupants. According to Clapman the cultural influences on dwellings need to be investigated through research based on qualitative methods, in order to capture and understand culture as a way of life of occupants. This view is also shared by Smith and Bugni, who argue that the form of the house is difficult to understand outside the context of its cultural settings (Smith & Bugni, 2006). Therefore, in attempting to gain insights into the relationship between the form of Italian migrants’ houses and the users’ cultural forces, this study employs a predominantly qualitative methodology. This is because insights into the cultural meaning that a material form has for individuals within a given social context can best be gleaned from the individuals themselves, and by exploring the rich symbolic universe within which individuals exist (Blumer, 1969).

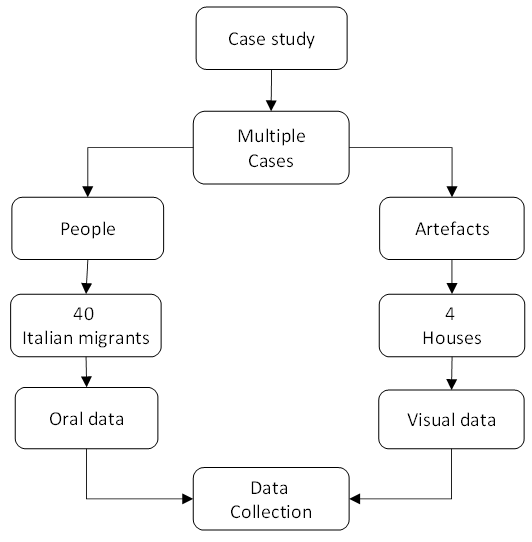

2.2. The Case Study

- Researchers stress that a case study is a research strategy based on an in depth investigation of a ‘case’, which can be an individual, a group, an object or event (Gillham, 2000; Merriam, 1998; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Stake, 1994). Ragin and Becker define the ‘case’ as an object bounded by a period of time and space or a process that may be theoretical and/or empirical (Ragin & Becker, 1992; Stake, 1995). As Yin (2003) argues, the purpose of a case study is ‘to portray, analyze and interpret the uniqueness of individuals and situations through accessible accounts; to catch the complexity of behavior and to represent reality’ For Yin a case study is defined as ‘an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, namely when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident’ (Yin, 2003, pp. 13-14).The investigation carried out in this current research is described as a single case study, including multiple cases or subjects, because the use of a number of subjects allows for greater variation. This study uses a case study strategy based on multiple cases to gather and analyze oral and visual data since individuals and physical artifacts, in this current research, form the cases to be investigated (2001, p. 223). Multiple cases were selected under the case study design because data from multiple cases can strengthen the findings (Yin, 2003, p. XV). In this case, the case study allows the researcher to draw upon the lived experiences, thoughts and feelings of the potential participants in order to understand the meanings of living in a house built by Italians in Brisbane. It will also provide qualitative data to be gathered from the self-built artifacts. The Diagram below shows the case study format based on an investigation of cases.

| Diagram 1. The case study format |

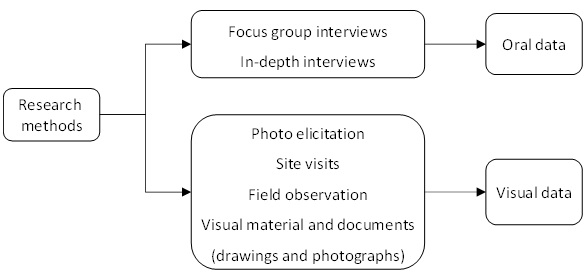

2.3. Qualitative Research Methods

- In adopting a ‘qualitative’ methodology, this research study inevitably draws upon multiple qualitative research methods (Creswell, 2003, p. 181). One of the most significant aspects of case study strategy is that varied methods are employed and combined, or triangulated, with the objective of exploring a case from different perspectives in order to ensure the validity of the case study research (Denzin, 1978). This process, defined by Johansson as triangulation, or ‘the combination of different levels of techniques, methods, strategies, or theories, is the essence of case study strategy’ (Johansson, 2003, p. 8). Therefore, to validate the findings within the current study, ‘triangulation’ from different sources (Yin, 2003, p. 159) is adopted. The methods employed in the research study enable the researcher to collect (1) oral data, through digitally recorded focus groups and in-depth interviews, and (2) material or visual data through photo elicitation, site visits, field observations and visual materials including drawings and photographs (Creswell, 2003). An integration of methods collecting both oral and visual data is considered essential for the purpose of this research study.

| Diagram 2. The research method format |

3. Findings

- The summary of findings is structured into two themes: (1) the intangible cultural heritage from the experience of Italian migrants through their 30 years long Italo-Australian journey and (2) the built heritage shown through the architectural and spatial form of the houses built in post WWII Brisbane.

3.1. The Intangible Cultural Heritage: Italian Migrants’ Experience

3.1.1. The Italo-Australian Migrants Journey

- In the early 1950s Italians migrated to Australia with the wish (1) to find economic security, (2) to financially support their families in Italy, and finally (3) to build a house for their own new family and/or open a business on their return to Italy. The idea of helping their extended families in Italy and creating economic security for their future family were the dominant factors, which gave them the courage to leave Italy. Italians migrating to Australia in the 1950s did not intend to settle in Australia permanently, and/or to build a house where to live with their family. They planned to migrate to Australia for a short period varying from two to five years. They assumed that during this period Italy would have recovered from the ruin of the war and therefore there would then be favorable conditions to return and settle back in Italy.By the 1970s interviewees had already spent approximately twenty years in Australia. This time had been a period of hard work and saving money, and most had not forgotten their initial plans to return to their homeland. It did not take from two to five years to achieve the economic security they had been seeking. It took them up to twenty years, and it also took the Italian economy twenty years to recover from the ruin of the war. It was only in the early 1970s that the Italian economy finally boomed in the form of the well-documented ‘Italian economic miracle’. Therefore, due to the favorable economic circumstances in the homeland, in the 1970s many of those migrants who had come to Australia in the post war period attempted to take advantage of the favorable economic conditions in Italy and returned. They wanted to settle in Italy, to build a house for their family and start up a small business, a dream they had been pursuing for twenty years.While many of them successfully settled in their native land, others could not cope with the Italian way of life, which had inevitably changed after their departure twenty years previously. In particular, Italy was revealed to be a country with a different culture, especially for the children of first generation migrants. This second generation were young adults and as result faced hardship in attempting to settle into a new cultural environment. After a year or so, this persuaded first generation Italian migrants to return to Australia, intending to live permanently in Australia.

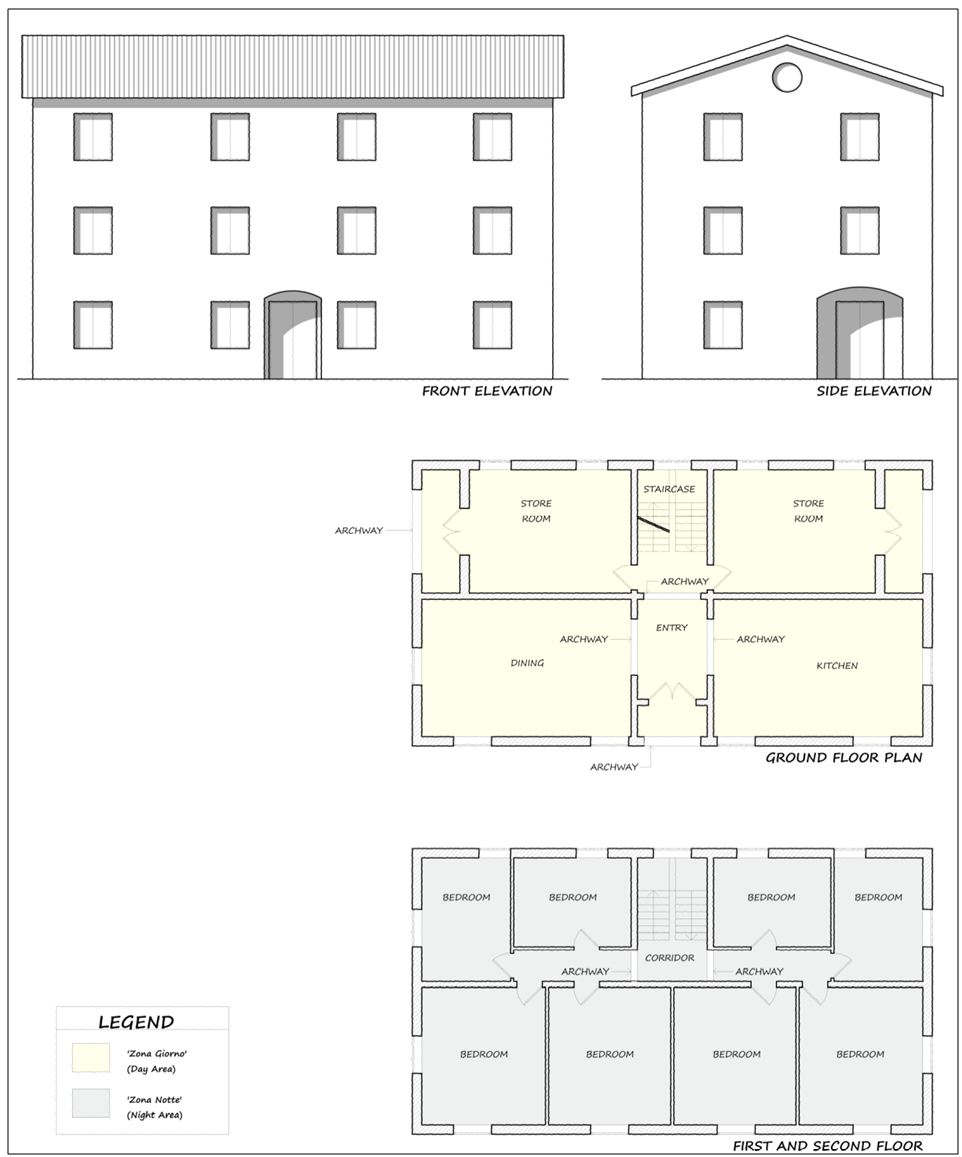

3.1.2. Migrants’ Housing Experience

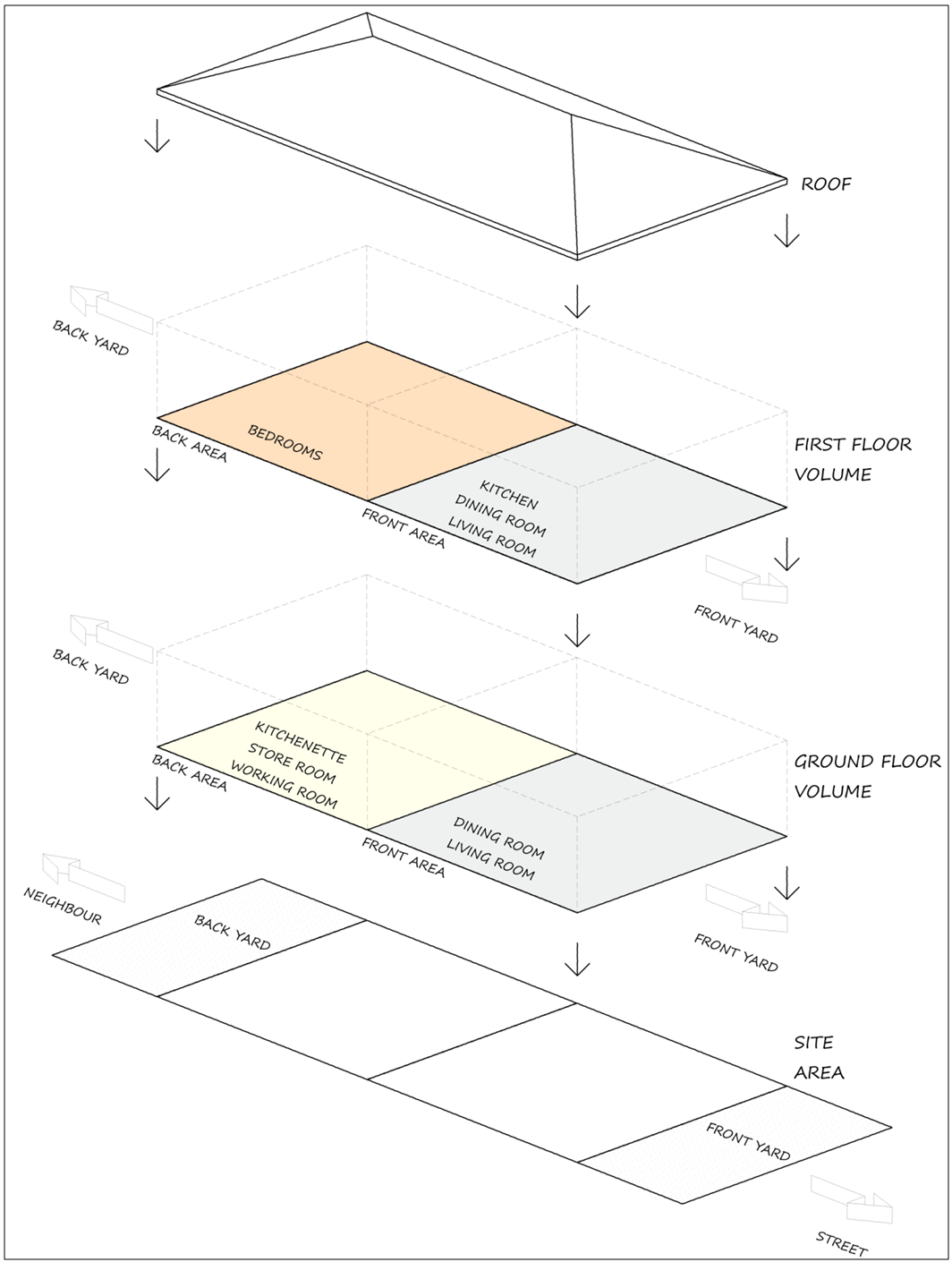

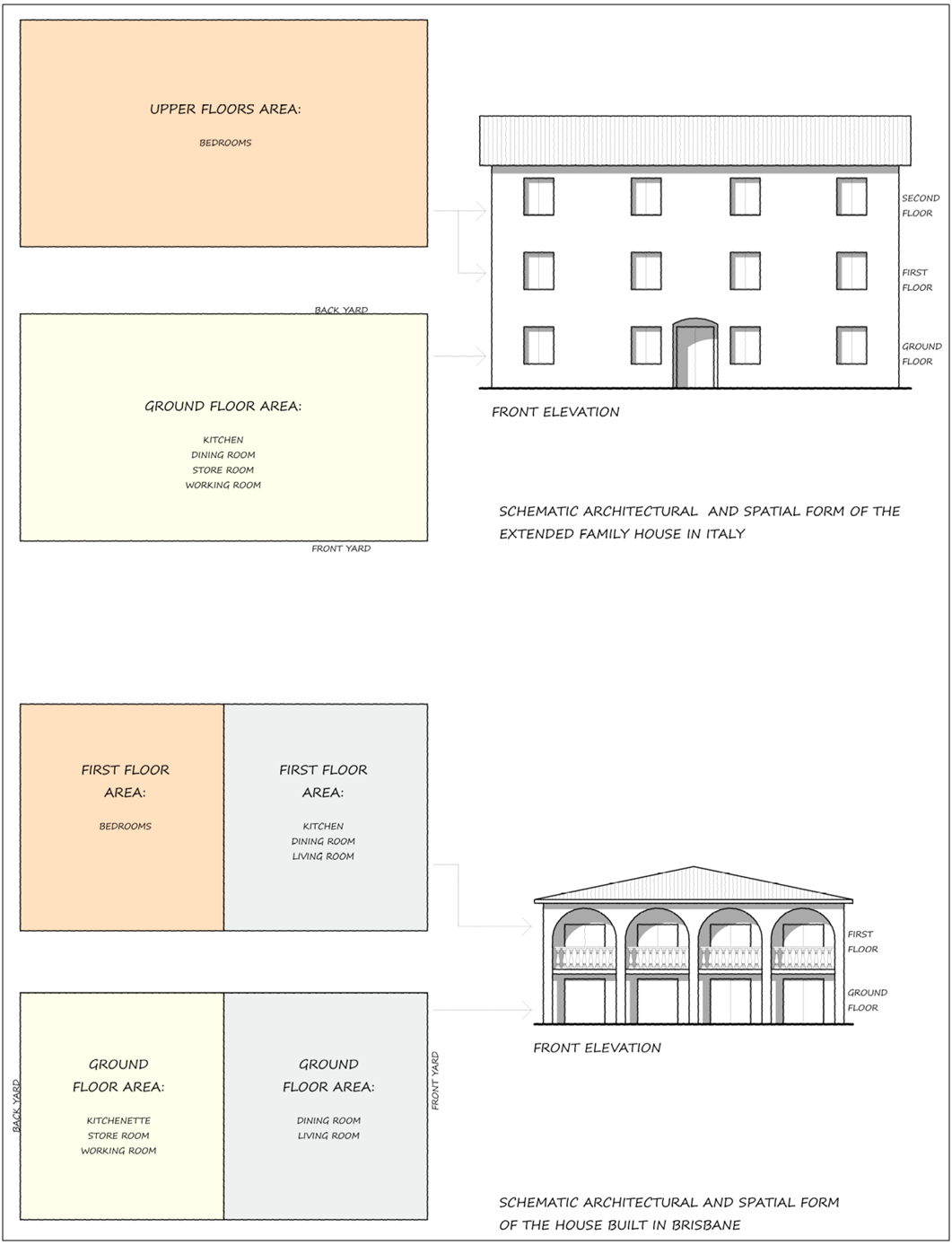

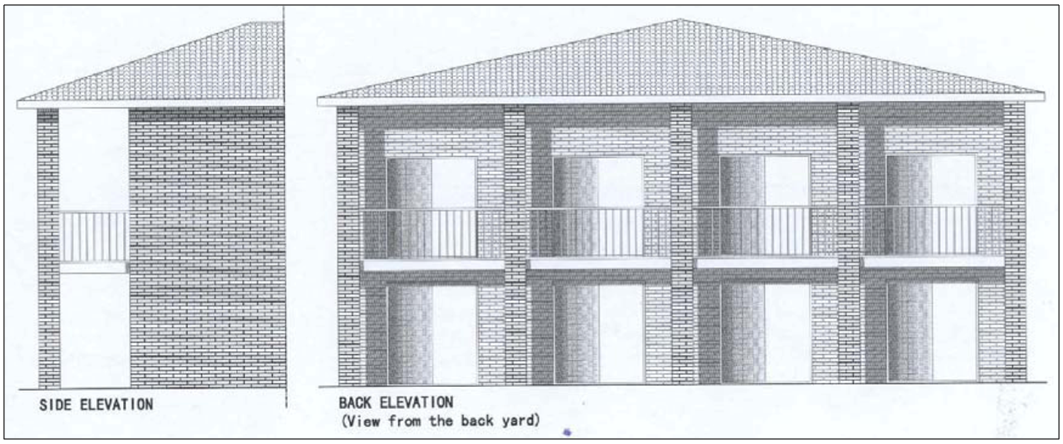

- The form of the houses in which Italian migrants resided in Italy and in Australia before building their own houses was investigated. The insights from this investigation could provide a better understanding of the extent to which previous housing experiences influenced Italian migrants’ way of life, and as a result the form of their self-built transnational houses. Before migrating to Australia most Italian migrants lived in large multi-story buildings (Fig.1-2-3), which hosted more than one family, because not many families had the opportunity of purchasing their own dwellings. Most of their houses were located in rural areas surrounded by land where the extended family were involved in a series of agricultural activities, such as growing crops, in order to provide income to support the family. The extended family multi-story houses presented a neat parallelepiped volume. The façades, built of bricks, were characterized by decorative architectural elements such as arches. The spatial form was also distinctive. While a day area (‘zona giorno’) used for daily activities was located on the ground floor, a night area (‘zona notte’) enclosing bedrooms was located on the upper levels (Fig. 4).

| Figure 1. Extended Family House in Italy |

| Figure 2. Extended Family House in Italy |

| Figure 3. Extended Family House in Italy (renovated) |

| Figure 4. Schematic architectural and spatial form of migrants’ extended family house in Italy |

3.2. Built Heritage: The Form of Italo-Australian Transnational Houses

3.2.1. Cultural Traditions Embedded in the Architectural Form

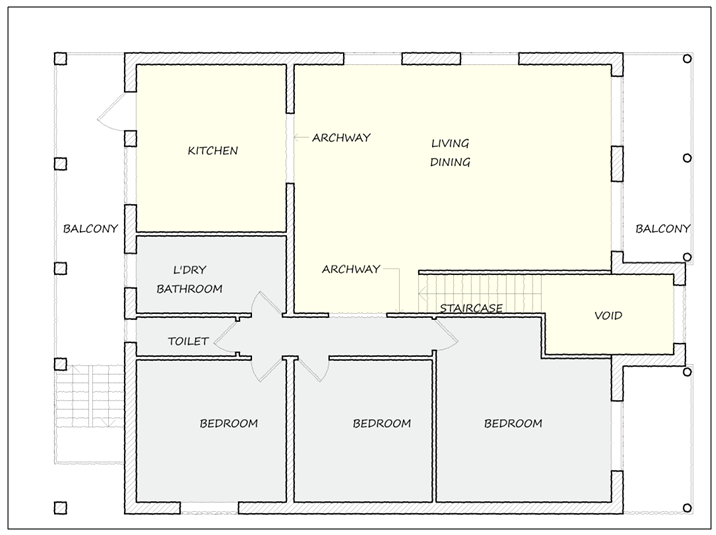

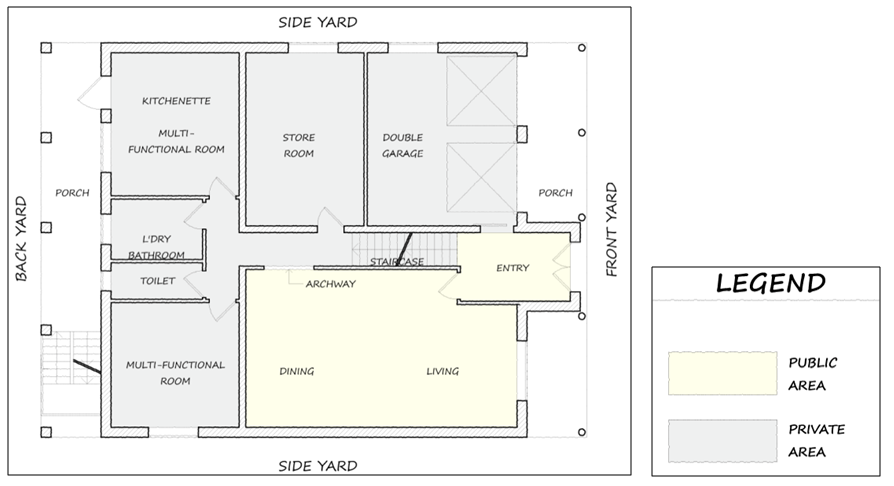

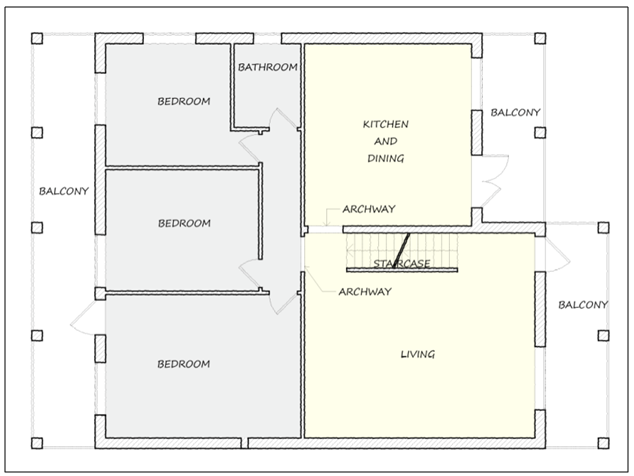

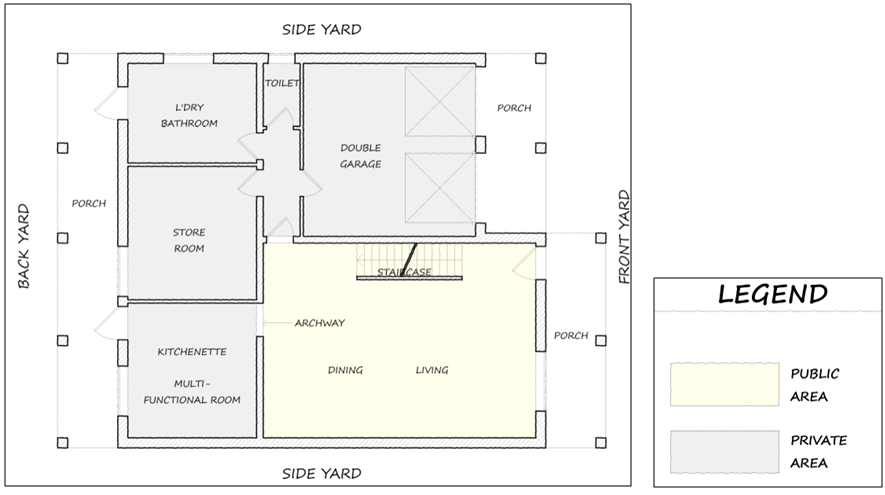

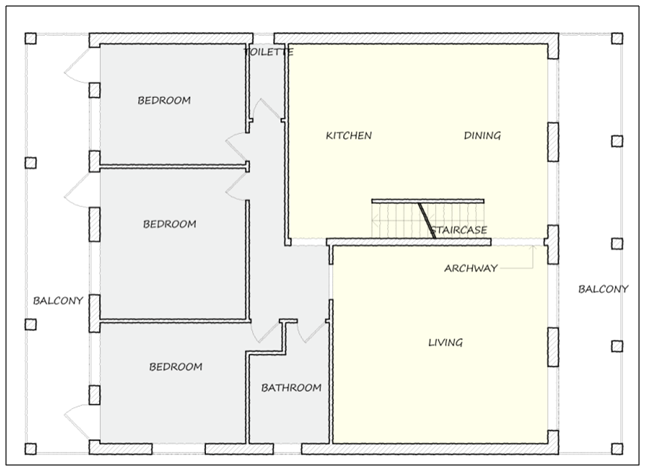

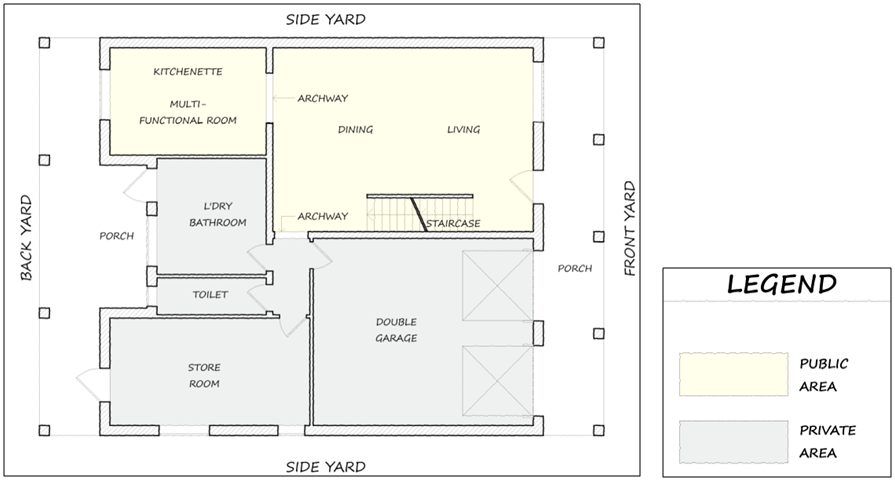

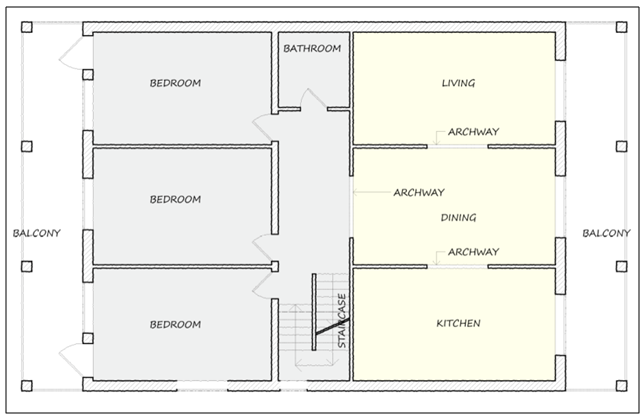

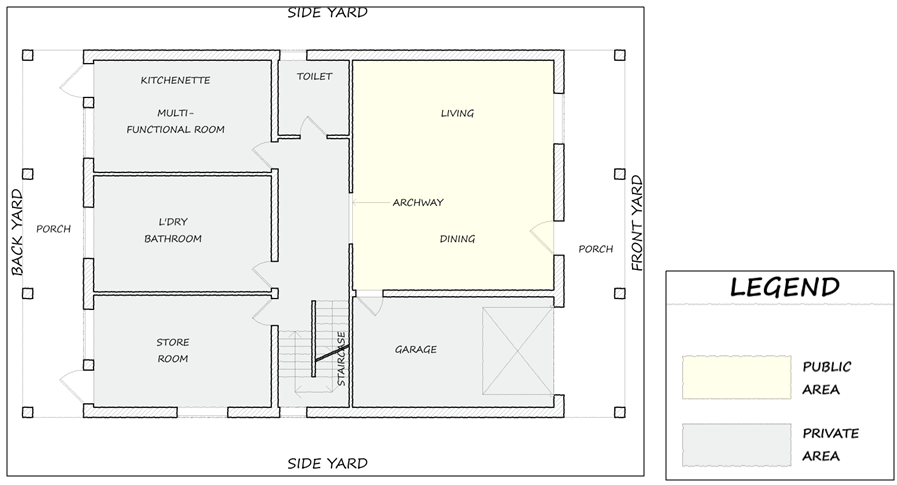

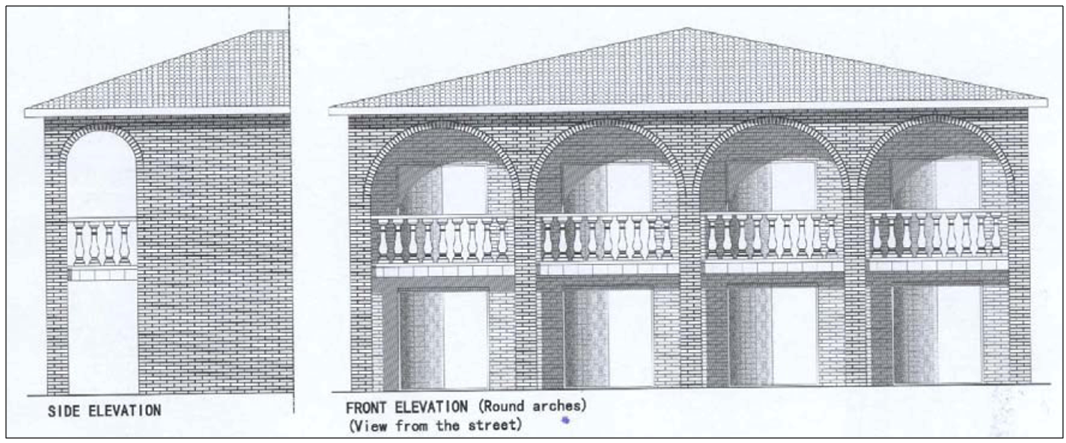

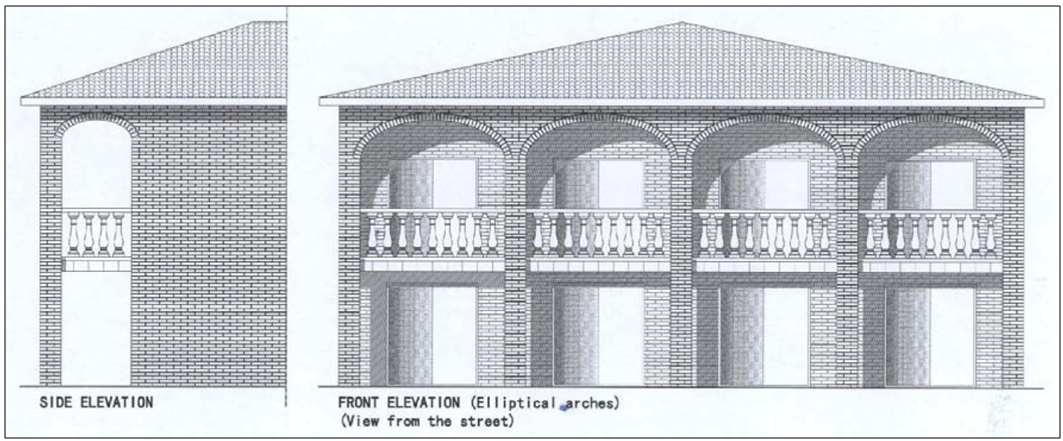

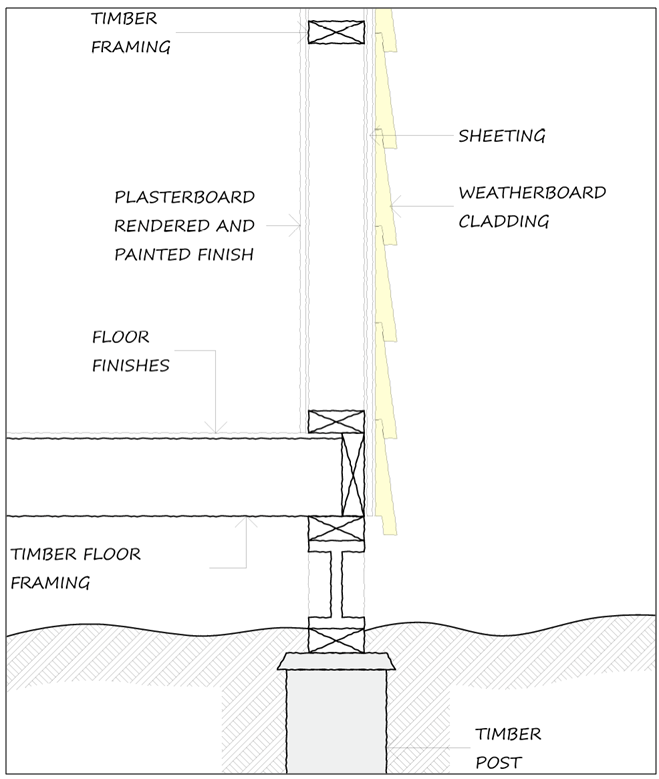

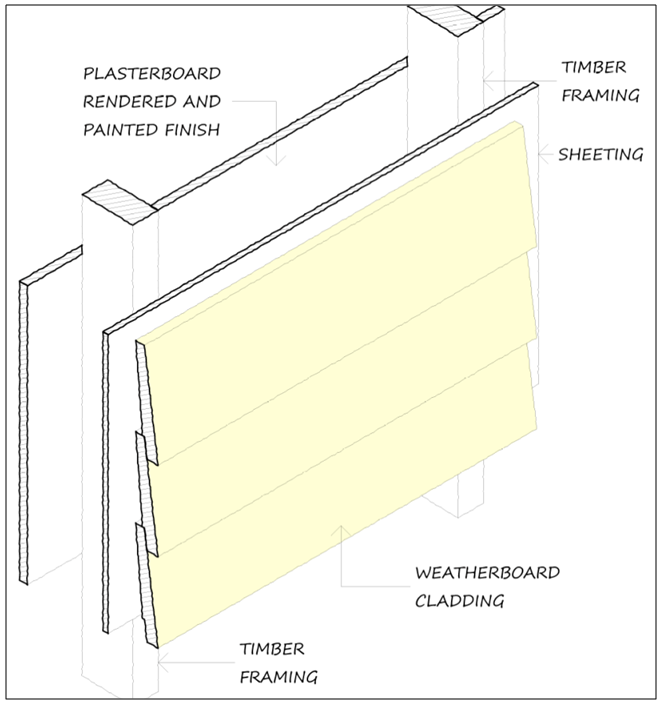

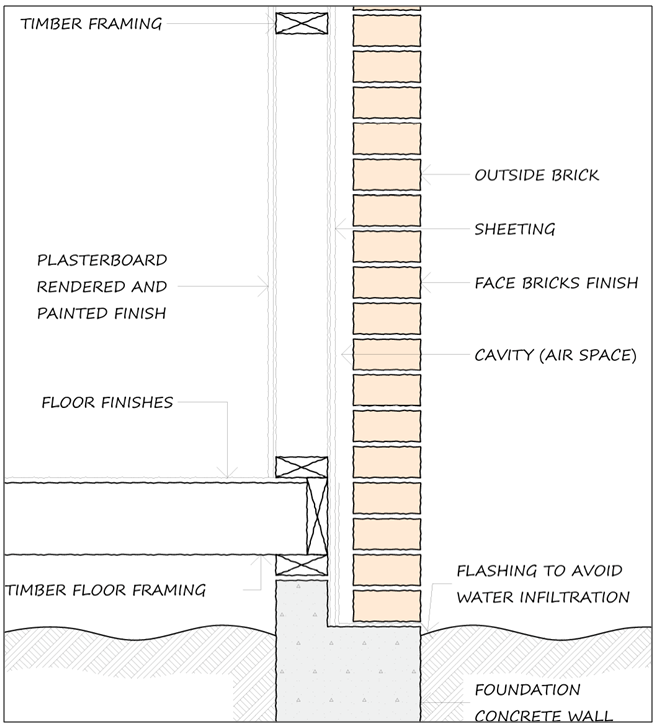

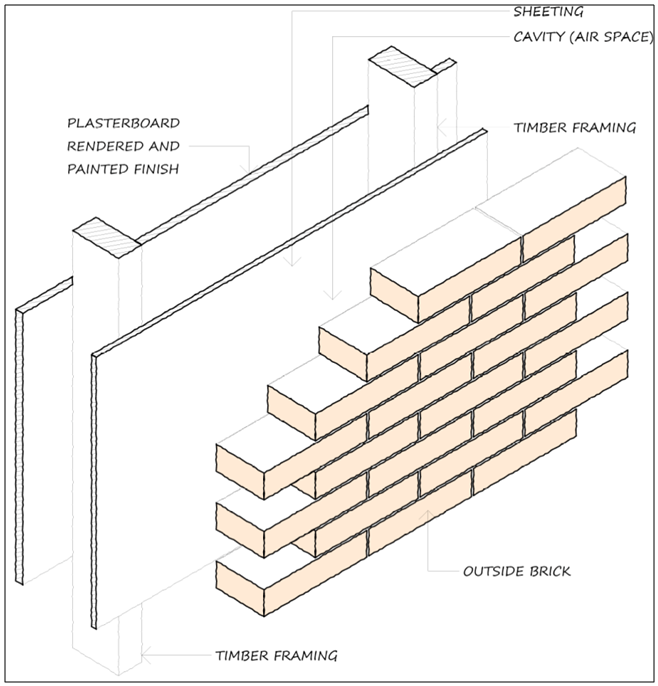

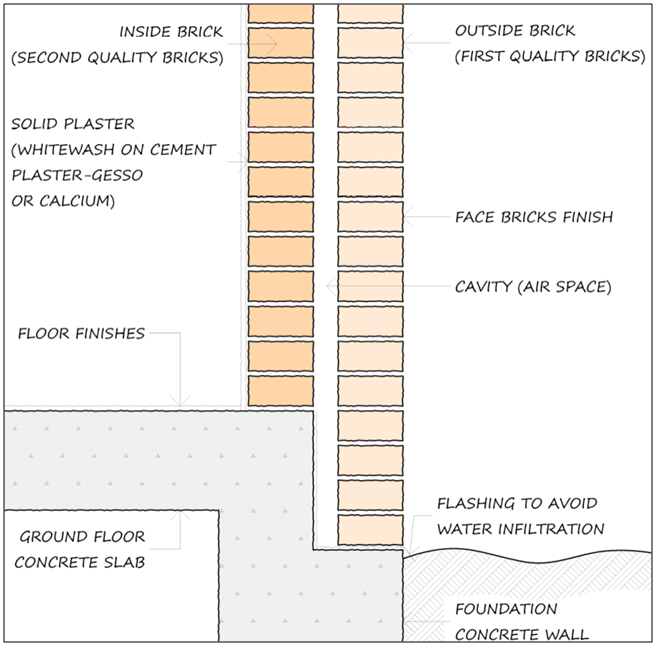

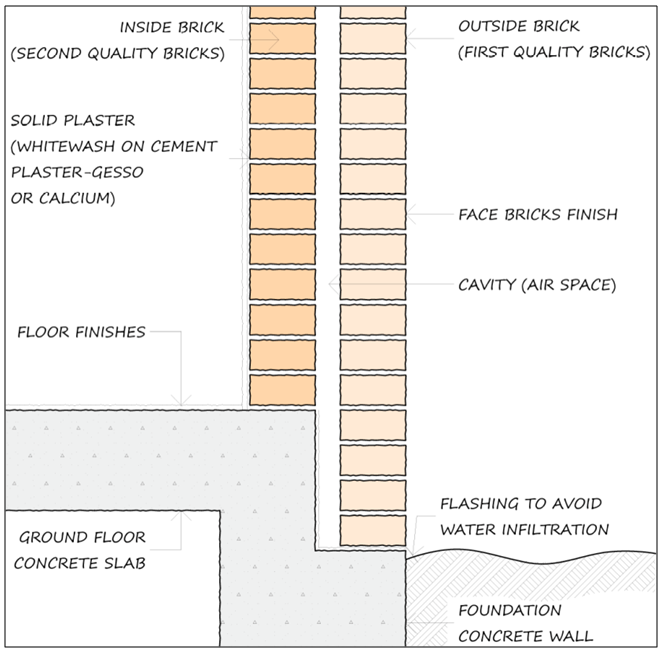

- The architectural form of Italian houses, which refers to (1) its levels, (2) materials and construction techniques, and (3) the decorative features visible on the main façades, were analyzed. Despite the commonality of single level houses in Brisbane, Italians opted to build a spacious two-levels house. This choice was influenced by two main factors: this type of building (1) allowed the users to have more space to be used to carry out specific daily activities and (2) recalled the tradition of the extended grand family house in Italy (Fig. 18). The large two levels house was the manifestation of their wish to continue the old tradition of the grand family house.Most detached houses in Brisbane up to the 1970s were built by the use of two different construction systems: the weatherboard and brick veneer techniques (Fig. 22-23-24-25). Italian migrants wanted a house constructed using a system called cavity brick (Fig. 26-27), which, as reported by the interviewees, was a technique not commonly used in the construction of dwellings in Brisbane. All interviewees stressed that the distinctive cavity brick construction technique was chosen because Italian migrants in Brisbane were acquainted with this construction technique as it was commonly used in Italy, therefore for traditional reasons. Interviewees pointed out that the multi-stories houses in which they lived in Italy before their departure were traditionally constructed using the cavity brick construction system. While in Australia some of them resided in weatherboard and others in brick veneer houses, all interviewed migrants chose to build a cavity brick house as a manifestation of physical stability, solidity, and durability. Therefore, cultural traditions, memory and migrants’ housing experiences, both in the homeland and in the host land prior to construction of their present houses, influenced the way Italian migrants built their own houses in Brisbane. The material utilized to build the external walls of the house, that is, the bricks, dictated the most common external decorative features visible on all the façades, the face brick finish (Fig. 5-8-11-14-19-20-21). Italian migrants revealed that this was not a feature visible in the houses in which they lived in Italy before migrating to Australia, since houses in Italy built using the cavity brick technique were usually rendered and painted. Therefore, in this case, the Australian brick veneer houses, where the external wall always had a face brick finish, influenced them. These external finishes did not require plastering and/or painting as happened in Italy, and consequently was maintenance free. Other features evident on all the façades of Italian migrants’ houses investigated are the porch and the balcony, the brick arches, the balustrade situated on the balcony on the first floor, differentiated by stainless steel patterned or solid white concrete columns, and the Roman pillars supporting the overhanging slab on which the balustrade sits (Fig. 5-8-11-14-19-20-21). The first architectural element, the porch and the balcony were not recognized as elements visible in previous Italian houses. The extended grand family house presented a parallelepiped shape with no projecting volumes. On the other hand forms visible in Australian houses influenced these architectural elements. The remaining features listed above were all influenced by architectural traditions learned in Italy. Interviewees explicitly pointed out the reasons for having these features on the main façade. Although they had decided to build their houses within the Australian host built environment, they still wanted to maintain an ‘Italian flavor’ on the main façade through the use of architectural elements, which, in their view, are recurrent on the façades of many residential buildings in Italy. By utilizing traditional architectural elements visible in the built form in their native country, they wanted to create a façade reminding them of their origins. This was also proved by the fact that Italian builders, craftsmen and the owners of the house in Brisbane did not have access to any formal architectural drawings of houses built in Italy – plans, section and/or elevations – and in the end the designs of the façades of their houses arose from traditions in their efforts to simulate, through memory, an Italian architectural design in Australia.

| Figure 5. Front façade of Italo-Australian house (case 1) |

| Figure 6. Ground Floor Plan (case 1) |

| Figure 7. First Floor Plan (case 1) |

| Figure 8. Front façade of Italo-Australian house (case 2) |

| Figure 9. Ground Floor Plan (case 2) |

| Figure 10. First Floor Plan (case 2) |

| Figure 11. Front façade of Italo-Australian house (case 3) |

| Figure 12. Ground Floor Plan (case 3) |

| Figure 13. First Floor Plan (case 3) |

| Figure 14. Front façade of Italo-Australian house (case 4) |

| Figure 15. Ground Floor Plan (case 4) |

| Figure 16. First Floor Plan (case 4) |

| Figure 17. Schematic spatial form (internal distribution) of the Italo transnational house in Australia |

| Figure 18. Comparison between the form of the extended family house in Italy and the Italo transnational house in Australia |

| Figure 19. Schematic front elevation – type 1 |

| Figure 20. Schematic front elevation – type 2 |

| Figure 21. Schematic front elevation – type 3 |

| Figure 22. Schematic section of a ‘Weatherboard Wall’ |

| Figure 23. Schematic axonometric view of a ‘Weatherboard Wall’ |

| Figure 24. Schematic section of a ‘Brick Veneer Wall’ |

| Figure 25. Schematic axonometric view of a ‘Brick Veneer Wall’ |

| Figure 26. Schematic section of a ‘Cavity Brick Wall’ |

| Figure 27. Schematic axonometric view of a ‘Cavity Brick Wall’ |

3.2.2. The Spatial Form: Human Behavior and/or Activities

- Italian migrants conceived the spatial form of their houses in order to (1) have a large space where the family could perform specific activities; (2) safely invest funds on a fixed budget; (3) achieve a prestigious plan; (4) show the family success; (5) have a new family house as grand as the one they had left in Italy; (6) build a brick and concrete house similar to the one in which they had lived in Italy, and in place of the house they could not find in Australia. The typical two levels Italian house (Fig. 6-7-9-10-12-13-15-16) allowed for more space to be used by the family to perform activities in response to their specific cultural needs. Therefore, the influence of the internal mechanism and organization of the activities performed by family members was the leading factor in decisions regarding the division and utilization of domestic space in these houses. More specifically, the activities performed by family members could be subdivided into two main groups: working and social activities. The pattern showed that working activities could be further divided into two sub-groups comprising domestic and income generating activities. The findings revealed that most domestic activities within the house were in turn related to food preparation and storage. These included making tomato sauce, pasta, ‘gnocchi’, ‘lasagna’, wine and other traditional foods and also the annual slaughtering of the pig and preparation of small goods. This occurred since (a) after their arrival in Australia, Italians could not find the types of food that they were accustomed to in Italy, (b) producing and storing food were activities performed within the extended family in Italy, and (c) Italian migrants were influenced by the memory of scarcity of food in Italy in the post war period.The domestic activities related to food preparation and storage were carried out on a daily basis in the kitchenette and in the back multi-use rooms located on the ground floor, near the backyard. This was influenced by a spatial tradition assimilated through the extended family house experience in Italy. The house of the extended family in Italy enclosed multi-use rooms on the ground floor, close to the kitchen used for the preparation and storage of food (Fig. 17).If on one hand, the activity of food preparation and cooking was informally performed on a daily basis in the kitchenette located on the ground floor, on the other hand cooking was also performed in a second formal kitchen located on the first floor. This occurred especially on weekends and in preparation for special events, and was related to social interaction. The kitchen, dining and living area on the first floor formed one large open space used mainly for formal events. The conformation of this space was partially influenced by the extended family house configuration where the dining and kitchen areas were unified. In the case of Italian migrants in Brisbane, they linked the living area to the dining and kitchen area, creating one large open space. In turn, this was influenced by migrants’ way of life in Italy, that is, by their need to enhance social interaction in a host environment.The need to perform income-generating activities, which were mainly related to food distribution, the building industry and the manufacture of clothes, also played a relevant role in the spatial distribution of the house. In turn these activities were influenced by the way migrants lived within the extended family in Italy, and by the need to make a living in Australia. The findings reveal that these activities were carried out on a daily basis in the multi-use rooms located on the ground floor at the back of the house.Migrants revealed that working activities were also subdivided by gender. The pattern shows that while wives spent much time in the kitchen preparing, storing and cooking food, husbands were more involved in income producing activities. As stated earlier, after working in the cane fields in North Queensland, many Italians moved to Brisbane driven by the wish to live in a less isolated built environment where they would have more opportunity to socially interact. As a result, the house was configured in order to allow social activities to be performed in a different context. More specifically, social activities were also subdivided into two categories: informal and formal social activities. The findings revealed that informal activities, such as the daily family dinner, the random meetings of the family and female friends and relatives, occurred in the living-dining area located on the ground floor, readily accessible through the front door of the house. Formal activities, such as the Sunday, Christmas, Easter and general holiday lunches were carried out in the open space comprising the living, dining and kitchen area, located in the front of the upper level.In the Italian migrants’ view, social activities were not facilitated by the host built environment: the host environment lacked an urban element typically used in the Italian built environment to interact with other people, specifically the town square. This means that the built environment had an impact on inhabitants’ social interaction. It was the need to carry out these activities, dictated by a culture or way of life, which influenced the way Italian migrants configured the spatial distribution of their houses. Thus, the study of the spatial form of the house cannot be isolated from the analysis of the built environment, since the social activities performed within the house are influenced by the range of activities performed in the built environment.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Findings: House Form and Culture

- The analysis of collected oral and visual data revealed that (1) the architectural form of the house (that is, the structure, the materials and construction technique, and the architectural elements visible on the façade), was influenced by cultural traditions, while (2) the spatial distribution and utilization of space, was influenced by human behavior and/or activities, filtered through 40 years of migration and past housing experiences. It was also revealed that the spatial form of the dwellings gradually evolved in response to the (b) configuration of the alien built environment. The findings showed that the form of the transnational house mirrors the cultures derived from the ways of life belonging to two societies, based on history and tradition. The form of houses built by Italian migrants in post WWII Brisbane is the manifestation of two developing cultures: the Italian and the Australian cultures.

4.2. Contribution to Knowledge: Built Cultural Heritage of Australia

- History is who we are and why we are the way we are. (McCullough, 2005)The assumption behind any historical approach is that one can learn from the past; studying the past is of value philosophically and it makes us aware of the complexity of overlapping of things, as it occurred in the case of post WWII Italian migrants in Brisbane (Rapoport, 1969, p. 32). In relation to Australia, history reveals that different cultural groups had an influence on the society and built environment. Indeed, if vernacular houses can be regarded as the direct reflection of cultural values, a multi-cultural nation such as Australia and more specifically its own built form provide an ideal site for exploring the ways in which a cultural group has expressed its own cultural identity through the construction of their self-built houses. Namely, the findings for this study contributed to a better understanding of how Italian migrants influenced the built form of the host Australian built environment and how cultural factors are embedded and preserved in houses’ built form, which nowadays represents the national cultural heritage of Australia. This exploration of a historically significant process of Australian domestic architectural development contributed to knowledge of contemporary Australian society.

4.3. Cultural Heritage Conservation

- The findings revealed that Italian migrants brought with them not just a luggage from their own country, but values, traditions, which belong to a culture. Their culture, in turn, was manifested in the form of their self-built houses. These houses, which belong to the built environment of Australia and have become heritage assets of Australia, should be preserved, to protect a culture, which now is Australian. As a participant stated: “Myself and my wife built this house in 1984. Nevertheless, this house does not belong to us. This house was built in Australia. Therefore, it belongs to Australia!” Historic places are living forms that carry many layers of significance. Preserving these buildings is a means of representing the national cultural identity of Australia, and of helping the society to a better understanding of who we are, where we come from and who we aspire to become. Built forms may be of significance because their remind people of their lives, history and culture. They are a clear manifestation of traditions, way of living, beliefs, memories, stories and culture of people that contribute to the past, contemporary and future cultural heritage of a nation.Conservation should be interpreted as a way enabling the continuity of intangible and tangible aspects of culture. By preserving these buildings, the built environment refers to the past and at the same time creates a link with its present and future. Besides, cultural and built heritage should be safeguarded and placed at the heart of development concerns. Cultural heritage should be considered an asset, which can support a sustainable urban development, encouraging investments and growth. The conservation of the built heritage cannot and should not be achieved by traditional, uncoordinated mono sectorial policies. A set of enforceable guidelines to govern actions for conservation and best practices for protection and preservation should be drafted and put in place to ensure that buildings are preserved as long as their form possesses meaning for the society.Namely, while the term ‘conservation’ of the cultural heritage in the widest sense indicates the policies, strategies, legal and technical measures, the term ‘protection’ refers to legal, managerial and professional actions, the word ‘preservation’ discusses those particular operations whose purpose is to prevent the deterioration of the state of the heritage. Heritage conservation refers to those actions that lead to the protection and preservation of the cultural heritage. Therefore, national, local authorities and institutes founded by municipalities or the state should enable (1) the determination of protection requirements in order to develop awareness of heritage, its significance and the protection tasks involved, (2) the development of policies and strategies for (A) spatial-urban planning, (B) the permanent management of monument buildings and areas (or conservation projects), (C) the allocation of budget funds for the protection and preservation of the cultural heritage, (D) the ensuring of high quality conservation activities and supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors thanks the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which contributed to an improvement of this paper, which is derived from the authors’ PhD thesis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML