-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2015; 5(2): 52-60

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20150502.02

Users’ Perceptions of Different Genders about Calligraphic Woodcarving Ornamentations in Malaysian Mosques

Ahmadreza Saberi 1, Esmawee Hj Endut 1, Sabarinah Sh. Ahmad 1, Shervin Motamedi 2, 3, Shahab Kariminia 1

1Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying, UiTM, Shah Alam, Malaysia

2Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

3Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences (IOES), University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Ahmadreza Saberi , Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying, UiTM, Shah Alam, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Mosques, as the house of God, have a boundless value among Muslims. They spend their time in mosques to pray to their God or listen to the religious speeches at least once a week. Although the mosques did not have any ornamentation in the early days of emerging Islam, the necessity of beautification has been a complicated subject among scholars. Woodcarving is a common type of decoration in Muslim countries, particularly in Malaysia and Indonesia, due to the availability of timber from the tropical forests. Woodcarving is known as a cultural heritage, which exists even before the arrival of Islam in these countries. The ornamentation was used in palaces, mosques and houses in varied patterns such as floral, geometry, animals, cosmos and calligraphy. Although several studies have been carried out on floral and geometric wood carving in Malaysia, far too little attention has been paid to calligraphy woodcarving decoration. The current study is conducted to reveal the perception of mosques users on the calligraphic woodcarving in Malaysian mosques. The data was collected through a questionnaire survey. For data analysis, the chi-square and cross-tabulation tests were employed to determine the relationship between groups of genders (Male and female) and the evaluated items such as ability to read and understand Arabic calligraphy, level of aesthetic, function of calligraphy in mosque ornamentations, combination of calligraphy with other motifs and the traits of scripts in the mosque users’ point of view. The data was analysed statistically to present the differences between male and female respondents. The chi-square test expresses that there is a significant relationship between male and female respondents on some variables such as skill of reading Arabic words, the opinion that this ornamentation is a requirement for mosques, the legibility and beauty of the calligraphic woodcarving and preferences of Nastaliq and Diwani scripts.

Keywords: Calligraphy, Woodcarving, Users’ Perception, Genders, Malaysian Mosques

Cite this paper: Ahmadreza Saberi , Esmawee Hj Endut , Sabarinah Sh. Ahmad , Shervin Motamedi , Shahab Kariminia , Users’ Perceptions of Different Genders about Calligraphic Woodcarving Ornamentations in Malaysian Mosques, Architecture Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 52-60. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to Nasir [1], evidences have shown that Islam came to Peninsular Malaysia in early 14th century. The development of Islam in the Peninsula Malaysia became more noticeable in the early 15th century during the time of the sultanate of Malacca [2]. Under the ruling of this kingdom, Islam spread to all regions in Malaysia. Malacca was then established as a prominent centre for the dissemination of religion in the territory. A large number of mosques in the vernacular architectural style were constructed to hold congregations and other activities linked to the teachings and spread of Islam. According to Ahmad [2], the construction style and materials of the buildings constructed during the mentioned period were similar to the vernacular Malay houses. Timber as the common material was used for the construction of such traditional buildings. Timber mosque as the national heritage for Malay rural societies can be found from the Northeast coastal states of Peninsular Malaysia to the Southern parts of Peninsular Malaysia [3]. Hence the need for beautification of religious buildings was considered by the designers.The current paper focuses mainly on ornamentations as an added value to the building. Muslims as the users of mosques have the right to contribute their opinion on the design of the building ornamentation. The floral and geometry patterns have been discussed qualitatively in numerous studies. However, there was a lack of attention paid to calligraphy woodcarving in Malaysian mosques despite the plenitude of this ornamentation.The building of the mosques is usually divided into two separated parts, as both genders need to pray in the same building. Since the praying space of men and women is different, the separate analysis was carried out to find out the perception of both genders about calligraphic woodcarving in Malaysian mosques. Moreover, it was claimed that the received perception of aesthetic is different between men and women [4]. Therefore, questions emerge when the subject of mosque ornamentations are discussed considering the fact that men and women prays in different spaces in a mosque. The quantitative approach in religious architectural ornamentations can be considered as an innovative methodological contribution. This study aims to identify the differences between male and female worshippers’ perception about this particular ornamentation used in mosques. The variables inquired included the ability of reading & understanding Arabic words, the aesthetic value of calligraphic woodcarvings, the function of this ornamentation, their opinion about combination of calligraphy with other motifs and finally the legibility and beauty of the woodcarvings and level of users’ preference to see this ornamentation in mosques. This exploratory paper is investigated the perception of mosque’s users quantitatively and provide opportunity for designers to understand the expectations of users about calligraphic ornamentations in Malaysian mosques.

2. Mosque as an Architectural Space

- The word “mosque” is generated from “Masjid”, an Arabic word literally derived from “Sujud”, which means prostration [5, 6]. The Quran defines mosque as equal to the place of Allah and a special place dedicated to the worship of Allah. However, in Islam, praying can be performed anywhere pure and clean. Thus, whatever the socio-cultural backgrounds and architectural styles, the provision of spaces and sitting should provide the Muslims’ religious needs. Nothing should diverge from the concept of the mosque and its relation to Islamic principles. Additionally, the mosque is also a place for Islamic teaching and in fact it represents a symbol of magnitude of Islam [7].

2.1. Concept of Mosques’ Ornamentation

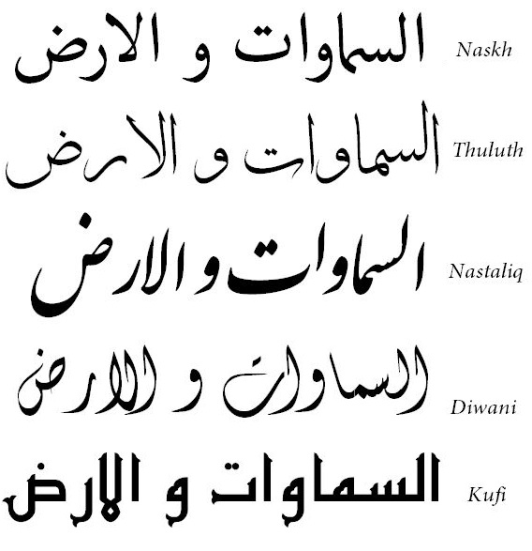

- The conception of ornamentation in Islamic art was and still is flexible in its characters, independent of its patterns, materials and scales, changing the whole space ambience. According to Hitam and Talib [6], prior to focusing deeper on particular ornamentation patterns in Islamic art, it seemed vital to categorise the variations in visual groups from the religious meanings and purposes. Mosques’ ornamentation may be different from one country to another or even from one region to another in one country. As an example, the way of ornamentation in Malaysian mosque is distinguished from the Saudi Arabian mosques, but it must be a little if not much effects from the past culture since they all originated from one religion, which is Islam. It is the key symbolic implication in Islamic art, which represents unity in diversity [8]. The Quranic calligraphy can be considered as the one of the similar ornamental patterns in mosques all over the world. Besides floral and geometric patterns, which have constantly been an ornamental element in Islamic art, Arabic calligraphy is regarded as an integral Islamic art feature. Researchers believed that calligraphic art is the ultimate Islamic art that converts the verses of the Quran into a visual artwork. Calligraphy in the general view is a simple joined letters and forms the simplest writing style (Naskh), or craftsmen softened it and make it angulated like the oldest Kufic inscription or in the most intricate shape, stretched, thickened, overlapped, prolonged and bent it like the Thuluth style (Figure 1). Furthermore, in the Middle Eastern countries, there are numerous calligraphy writing styles such as Diwani, Riqa’ and Nasta’liq in addition to Kufic, Naskh and Thuluth being applied in ornamenting Malaysian mosques’ interior and exterior.

| Figure 1. The common Arabic calligraphy scripts |

2.2. Types of Motifs Applied in Malaysian Mosques

- After the arrival of Islam in Malaysia, Islamic calligraphy was also introduced to the craftsmen, giving them an inspiration to produce a new motif in wood carving using Arabic inscriptions. In some cases, it is accompanied by other traditional motifs such as geometric, floral. The mentioned types of motif can be seen abundantly in the Malaysian religious buildings’ decoration. Therefore, it can be concluded that there are three types of motif still being implement in the Malaysian mosque; floral, geometric and calligraphic. Floral motifs as the dominant motif among other Malay wood carving motifs obtained its reputation due to the abundance of tropical plant species and also dense forests in Malaysia which inspired the wood carvers to manifest them in their crafts (Figure 2). However, the animal and cosmos patterns were not preferred as figurative patterns are prohibited in Islamic art.

| Figure 2. Wood carving in floral motif (the symbol of pomegranate fruit and local Malaysian plants is demonstrated in the panel) |

| Figure 3. Geometrical woodcarving displayed in Islamic Art Museum in Kuala Lumpur |

| Figure 4. Divider Panel in Masjid Kampung Hulu, Melaka |

3. Arabic Calligraphy Development

- Although calligraphy has been defined as handwriting, numerous statements existed from past literatures, which introduced it as “pleasant writing” [12]. In the Islamic world, the art of calligraphy has always been of high importance among Muslims scholars due to its relation to the religion. Besides the endless creativity and flexibility of calligraphy in the Islamic region, transmitting a text and exhibiting its meaning in an aesthetic form is a unique trait of calligraphers (Figure 5).

| Figure 5. Arabic calligraphy in the shape of a bird |

3.1. Arabic Inscription Implemented in Architecture

- Artistic Arabic inscriptions played a principal role in Islamic architectural ornamentation. The application of architectural inscriptions came back to the period of the classical antiquity where the scripts were used for decorative purposes as well as recording events. The Umayyad was the first Islamic dynasty started to implement inscriptions in architectural ornamentation and continued the epigraphic traditions in the Islamic territory by ordering inscriptions on stones and mosaics [5]. However, Hillenbrand [5] claimed that the peak time for this particular art was in the 11th and 12th centuries (Seljuk Empire) as incredible epigraphic creativity in the eastern Islamic lands emerged and imaginative designers developed novel methods of writing to convey Quranic messages in varieties of scripts.

3.2. Location of Inscriptions in Mosques

- In Islamic point of view, a mosque is defined as a place where the congregations can perform the worships and prayers [13]. The importance of ornamentation and its location has always been a controversial issue among architects and designers. From a variety of components in the mosque’s prayer hall, the entrances, mimbar windows, Mihrab wall and sidewalls are additional surfaces to display the wood carved calligraphy as decorations.

3.3. Calligraphy as a Decorative Element or Praise Allah

- Undoubtedly, human ingenuity played a vital part in the development of the sacred art. In art, which is connected to religion, a distinction must be made between sacred art in the strict sense and art, which is religious without being sacred, such as, floral or geometric [14]. Calligraphic decoration was an art form that Muslim invented and implemented for years. The sacred art can be defined as religious art through criteria of authenticity. The function of the sacred art is to make the viewer appreciate the existence, as well as the greatness the divine being or God [15].In Islamic calligraphy, the act of writing Quranic verses or any portion of this holy book is a religious experience rather than an aesthetic activity [15]. However, in the West, calligraphy has always been a subordinate art to figurative art. Therefore, the main function of Islamic calligraphy as an architectural ornamentation or a way to praise the God is also a debatable subject.

3.4. Meaning of Abstraction in Islamic Art

- In the early years of Islam, the concept of the arts was not under consideration in Islamic scope due to involving in the conquest of lands. Although after almost a century of stability, the lack of artistic values in architecture was sensed among Muslims. While the advent of Islam into the South Eastern part of Asia and particularly to Malaysia was in16th century. The Malay traditions started to adapt its lifestyle with the teachings of Islam. In Islam the concept of meaning was always manifested in the abstraction or symbolization which in woodcarving decorations this conception was unveiled in three different categories. Floral or arabesque, geometric and Calligraphy used in a variety of architectural components; such as, structural, elemental and ornamental components as a cultural heritage which must be conserved from being neglected.

4. Users’ Perception

- The term “users’ perception” has been prevalently used for around 100 years. In the early 20th century, scholars attempted to define the term. Peters [16] described user perception as “an answer which comes out from a social investigation, rather than governmental speculation”. Most social scientists judge user perception to be a product of democracy in the society through rationality. While the second aspect lead the society to collectively voice their opinion and to ensure that there is a sufficient level of general agreement on which decisions and actions may be based. The research about the interpretation of the ornamental aspect of architecture in places of worship shows two general trends. The first one argues that the ornamental value of architecture originates mostly from its connection with belief values representing a religion and the second value is rooted from the connection between the place and individual daily users [17-19]. The combination of these views can lead us to the most favourable result, which is to understand the users’ perception towards the aesthetic and function of ornamentation in a religious daily used architecture. Ahn [19] claimed that designers could also help to enhance the old fashion paradigms in architecture by referring to the broad social, religious and cultural contexts of an era through this view.The literature explained two ways of data collection for assessing user perception, mass mediated exchange and face to face including questionnaire and interview. Both ways contribute to the formation of user perception though in clearly different methods. The face-to-face method, which represents a very common type of communication, is referred to as direct contact method [20]. It consists of the most convincing form of communication between the researcher and individuals. The mass mediated method is another way of asking public opinion through broadcasts. Researchers also approve the second method. However, direct contact can be more precise based on the subject of the present study, which is an assessment of users’ perception on mosque interior ornamentations. Therefore, the researcher found the Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) theory as the most suitable method of data collection.

4.1. Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE)

- Based on the mentioned study, the researcher decided to apply the Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) method and develop the questionnaire according to the factors that must be assessed. Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) has been introduced and developed by Preiser [20] and later used as the assessment technique by several researchers. The most common definition of POE is the assessment of users’ perception of a building in service, from the perspective of the people who use it. It evaluates how well a building meets users' needs, and recognises ways to enhance building design and performance for a purpose.POE is considered as the Evidence-based design technique, where the outcomes usually help the designers to have an appropriate refurbishment project and address the past issues. Therefore, the evaluation of users’ perception towards the calligraphic woodcarving decorations in existing Malaysian mosques can be considered as POE evaluation since the assessment is performed within an existing building by the users.

4.2. The Knowledge and desire of Users on Aesthetic and Function of Ornamentation

- According to Rapoport and El Sayegh [22], people tend to assess their environment based on several aspects such as the aesthetic and functions of objects through their desire and knowledge. The assessments are according to their knowledge consciously or unconsciously. They claimed that the combination of two different concepts of architectural ornamentation as function and aesthetic could affect people’s assessment if they were asked separately. Therefore, researchers have proposed that the concepts of knowledge and desire as people’s assessment tools must be questioned with the function and aesthetical level as the two significant aspects of architectural ornamentations [23, 24].

5. Methodology

- Questionnaire can be recognised as one of the methods of survey for data collection. In this study, feedback from mosque users as respondents was gathered through using group administered questionnaire method. Bryman [24] confirmed that this method is a suitable technique for data collection from a wide population samples and therefore, it could be applied in a social science study, which applied POE technique based on topics connected to public assessments. The questionnaire for this study was based other research methods gathered from the literature review and, guided by the objectives of the study. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were assessed before running the survey. The questionnaire was translated to Bahasa Malaysia in order to be understood by all participants with every education level. The Likert 5-point scale was applied to obtain accurate answers from participants for each question. The questionnaires were distributed in four mosques which are located in different states. Kampung Keling and Al-Azim mosques in Melaka, Sultan Alauddin mosque in Jugra and Abu Bakar mosque in Kuala Lumpur were the selected mosques for the study. The survey was started in May 2013 and finished in July 2013. The mosques have calligraphic woodcarving ornamentations inside their main prayer hall, mainly used in mihrab and mimbar.

5.1. Sample Size for Questionnaire Survey

- As a part of data collection in the quantitative method, scientists generally tend to examine a hypothesis and interpret the results on a large population rather than a small group of respondents [26]. Creswell [26] claimed that a sample size of 350 to 400 is necessary to acquire a confidence level of 95%, along with a confidence interval of [p = 0.05], for a quantitative survey sample between 1000 to 1500 population. Therefore, the numbers of 400 questionnaires were distributed randomly among the worshippers. From the total of 420 questionnaires, 408 of them were completely answered and input to the software for analysing.

5.2. Statistical Methods

- In social science studies, statistical analysis works like the heart of the research. Since it is extremely difficult to acquire general and universally valid theories in the social areas, selecting appropriate sample size and performing statistical analysis may help researchers to propose scientific theories that are near to facts. Chi-Square and cross tabulation analysis have been used for the study. The type of analysis has been selected based on the research design, the objective of the study, characteristics of the variables and whether the assumptions needed for a particular statistical test are met. A crosstab shows the joint distribution of two or more variables.

6. Results

- This study focuses on the perception of mosque users about the calligraphy wood carving ornamentation in the selected mosque in terms of the role of calligraphy in the prayer hall of mosques, the aesthetical aspects, the preferred writing styles and the most appropriate potential location. The analyses revealed the knowledge and preference of calligraphic style with regards to their personal evaluation.

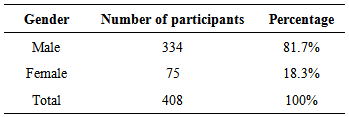

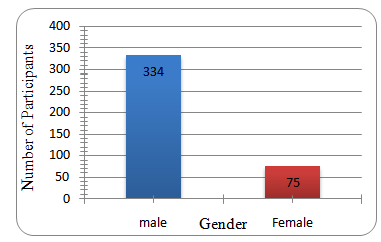

6.1. Description of Statistics on Gender

- In terms of gender, from the total of 408 participants of the study, 334 of them were male which is equal to 81.7% of respondents [Table 1]. However, the numbers of female participants were not as many as the male since the surveys were usually carried out after the Friday prayer. Hence, only 75 or 18.3% of respondents were female [Table 1]. It was one of the limitations of the study due to difficulties of conducting the survey in the women section of the mosques as fewer women come to the mosque for Friday prayers since Friday pray in an obligatory only for men. The Figure 6 demonstrates the number of men and women who participated and completed the survey.

|

| Figure 6. Gender distribution of respondents |

6.2. Correlation Tests of Research Questions

- The inferential statistics are used to infer what the population might believe from the data collected from samples of study. Therefore, inferential statistics have been used to make predictions from our data and to generalise conditions on the population. Since the variables of the study have been evaluated through the formative method and Likert scales, the answers are considered in the ordinal form. If the data was not distributed normally, or the skewness and kurtosis of data were not between -2 and +2; non-parametric tests must be applied in order to analyse the data. The crosstab statistical analysis is applied to test the variables of the study. There were 408 respondents who fully answered the survey while attending prayers at the mosques. The unequal sample sizes are not an issue since SPSS offers an adjustment in the cases of unequal sample sizes. Through the comparative mean, researchers are able to calculate sub-group means and connect univariate statistics for dependent variables within groups of one or more independent variables in order to obtain a one-way analysis of variance. A table cross-tabulating with categorical variables can describe the relationship between demographical variables as the independent variables and the measured items as dependent variables. Cross-tabulation and the chi-square statistic can answer research questions such as "Is there a relationship between the level of study and the characters of scripts?” Chi-Square allows the researcher to verify whether there is a statistically significant relationship between a nominal variable and an ordinal one. The analysis demonstrates the observed and expected frequencies in each evaluated group to test whether all the groups include the similar proportion of values.

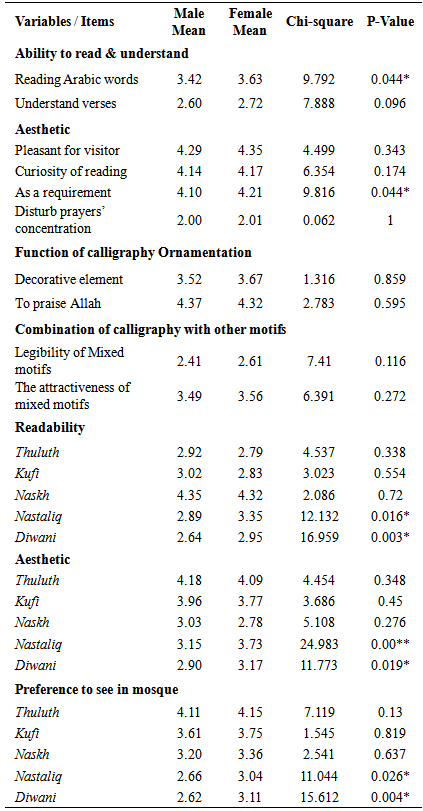

6.3. Test the Variables based on the Groups of Genders

- The cross-tabulation test was used to determine the relationship between groups of genders (Male and female) and the evaluated items namely ability of reading and understanding of Arabic calligraphy, level of aesthetic, function of calligraphy in mosque ornamentations, combination of calligraphy with other motifs and the traits of scripts in the mosque from users’ point of view. The table 2 shows the results of the test for each individual item. The chi-square test results in Table 2 expresses that there is a significant relationship between examined participants’ genders and skill of reading the wood carving calligraphy ornamentation in Malaysian mosques χ2 (2, 408) = 9.792, p< .044. It must be noted that, the mean of female respondents (M=3.63) who are able to read Arabic scripts was higher than male (M=3.42) participants. While, there is no significant relationship between persons’ genders as the independent variable and understanding the meaning of Quranic verses as dependent ones. Similar to the ability of reading Arabic scripts, the mean of female group (M=2.72) is higher than male respondents (M=2.60) in terms of understanding the meaning of Quranic scripts, which have been used in Malaysian mosques as wood carving ornamentations.

|

7. Discussion and Conclusions

- The current study is considered as an exploratory research since no past studies were found on mosque ornamentations and their association with users’ perception through quantitative method. The data, as presented in the current paper, shows the uniqueness of the topic and the findings are useful for designers and architects as well as the ordinary people who visit the building for worship. There are numerous literatures on wood carving ornamentation namely floral, geometrical or calligraphic, but they investigated this art through qualitative method. The opinion of people who used this place has always been neglected since the designers prefer to follow their own intuition or apply their own interests in the work. However, the current study determines the users’ feedbacks on the calligraphic wood carving ornamentation, which are used in the mosque in terms of their gender. In the study conducted by Shahedi, Keumala, and Yaacob [24], the assessment of respondents’ answers is discovered to be more detectable and meaningful by their knowledge of architectural elements and its ornamentation. Moreover, culture, religion and moral concerns are also connected with the respondents’ perception, even though; some of them gave different answers to the interview questions, which shows the variety of opinion among participants. However, the lack of knowledge and different opinions in architectural ornamentation was the main sources of diversity in answers. Meanwhile, in the current study, the respondents showed that their interest in architectural ornamentation is enhanced and they tended to express that the calligraphy wood carving ornamentation is mainly to praise the God than as the ornamental element in mosques. According to Ghomeshi and Jusan [23], humans’ sensations including visual ability can affect their environmental evaluation and perception. They believed that aesthetical value in architectural ornamentations is now an independent field of investigation and it must be segregated from other outlooks of architecture. Aesthetical value in architectural ornamentation concentrates on the appreciation of the environment and how it affects our feelings in a pleasurable way. Specifically, Ghomeshi and Jusan [23] proposed that architectural aesthetics is concerned with the intersectional point between physical attributes of the human environment as the objective target and the subjective matters such as culture and religion.There is an opinion that artistic productions are derived from the mutual relation between human and several factors such as their environment, culture and religion [27]. They also claimed that architectural ornamentations are notable examples of the reciprocity of the outcomes of this interaction. Therefore, it also can be viewed that the ornamental aspects of architecture as the fine arts are characterised by the manifestation of collective human desires through their knowledge about the interaction with human’s attributes.In a study conducted by Najafi and Kamal [28], the researchers evaluated users’ perception with regards to the attachments of mosques in Malaysia. They reported that the respondents described places as meaningful and beautiful simultaneously. In this regard, several years ago, Tuan [28] stated the role of aesthetic in the sacred and religious places. He stated that the aesthetic aspects of religious places, which are usually sensed by the users, could influence their perceptions and allow them to easily understand the glory of the creator. Tuan also [30] discussed that aesthetic manifestation in architecture may satisfy human emotions and desires. Therefore, physical features and visual appearance of architectural ornamentation not only can enhance the engagement of users’ perception of the context, but it may enable them to utilise physical senses to comprehend the function of them. In this regard, the respondents of the conducted surveys not only shared their knowledge but also they can express their desires and preferences concerning the matter [29].The point that there are no significant differences between male and female respondents in terms of the majority of inquired variable can be regarded as a positive attribute of both genders. The findings will help designers to select the most appropriate design for ornamentation. Since prayer place for men and women is in the same prayer hall and only a panel divides them, the decorations of the prayer hall are legible to both genders.The significant level of difference was found in the factor of readability skill which female showed that they can read calligraphic woodcarving ornamentations easier than men congregations. In terms of different scripts, the results show that the Thuluth, Kufi and Naskh are styles which the designers and calligraphers can use to create inscriptions as both genders had a similar point of view about them. While application of scripts such as Naskh, Thuluth and Kufi can be used in other locations of prayer hall for example windows, entrances, Mimbar, Mihrab and side walls. In must be noted that among all suggested scripts, Thuluth writing style was the most popular which help designers to select it as the common script as calligraphic woodcarving ornamentations in Malaysian mosques. However, In terms of Nastaliq and Diwani, Female participants showed significant differences from the men. The level of legibility, aesthetic and preferability of Nastaliq and Diwani were more appropriate for female participants than men. Therefore, designers can focus on using and applying these two types of writing styles for only women part of prayer hall. The only location which seems to be the most appropriate one for demonstrating calligraphic woodcarving ornamentation in women space is dividing panel. Designers are suggested to concentrate on dividing panel which is necessary for every prayer hall of mosques.

Notes

- 1. Mimbar is a lifted platform for the orator of mosque to stay on it and speak to the people.2. The Mihrab or prayer niche is the “physical manifestation” of the Qibla; and the wall which mihrab is installed on it is mihrab wall.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML