-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2015; 5(2): 31-51

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20150502.01

The Spatial Form of Houses Built by Italian Migrantsin Post World War II Brisbane, Australia

Raffaello Furlan

Qatar University, Qatar; University of Queensland, Australia

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan, Qatar University, Qatar; University of Queensland, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The literature reveals that despite the study of the relationship between human behavior, activities and built form has focused on physical spatial environments at any scale, ranging from built environment to built form, the investigation of micro-scale housing has been neglected in the past. Namely, regardless of the interest to this relationship, direct assessment of the extent to which migrants’ human behavior and activities influence and are also influenced by the spatial form of their houses is still rare in the field. This paper focuses on the exploration of the relationship between human behavior, activities and the spatial form of houses built by Italian migrants in post WWII Brisbane. The paper argues that the spatial form of migrants’ houses was influenced by two factors: the need to perform working and social activities dictated by culture as a way of life; urbanization patterns present in migrants’ native and host built environment.

Keywords: Migrants, cross-cultural studies, Culture, Transnational houses, Spatial form, Working and social activities

Cite this paper: Raffaello Furlan, The Spatial Form of Houses Built by Italian Migrantsin Post World War II Brisbane, Australia, Architecture Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 31-51. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20150502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Dwellings stand as the concrete expressions of a complex interaction among cultural skills and norms, climatic conditions and the potentialities of natural materials (P.L. Wagner cited in Chandhoke, 2003, p. 70).The house, the place where people share their private and intimate life with family members on a daily basis, is interpreted as the physical expression of interacting cultural factors. In this paper I review the classical theory of the discipline of Architecture by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (born c. 80-70 BC, died after c. 15 BC), the first Roman writer, architect and engineer to have written in this field. In his very earliest surviving and much-celebrated treatise on the subject, ‘De Architectura’ (translated as ‘The Ten Books on Architecture’), dedicated to the emperor Augustus, he declared ‘Firmitas’ (stability), ‘Utilitas’(utility), and ‘Venustas’ (beauty) to be the three essential attributes of architecture (Morgan, 2005). However, aside from the structural, the functional and the aesthetic (Nöth, 1990, p. 436), Vitruvius stressed the importance of culture which is fundamental to the field of architecture. In fact, we can see the significance of this element in how he defined architecture, ‘[Architecture is] … the art and science of designing buildings and structures, addressing aesthetics, function and cultural purposes.’ (Morgan, 2005, p. 68).Vitruvius’s classical view of the discipline is also shared by contemporary scholars. For instance by Amos Rapoport (Rapoport, 1969, 1982a, 1982b, 1997, 2000) and Paul Oliver (1997), who stresses that the built form, namely in a vernacular or transnational housing context, is not only shaped in order to create shelter, but in response to specific needs which inevitably are expression of the users’ cultureor simply cultural needs, dictated by a way of life.He highlights that vernacular houses, defined as those artifacts built by their users within a bounded cultural and traditional context and in a more spontaneous way in comparison to high style buildings designed in a professional environment, are ‘the direct and unself-conscious translation into physical form of a culture….’ (Rapoport, 1969, p. 2). In addition, he states that transnational houses are, in fact, vernacular houses, in that they are built in a host built environment by a migrating group sharing a cultural frame. Therefore, he concludes that the form of transnational houses can also be considered a physical manifestation of culture, as a way of life (Rapoport, 2000, p. 129).Despite classical and contemporary scholars’ views emphasizing the determinant influence of cultureas a way of life on the built form, an investigation of the literature reveals that, in the contemporary development of the built environment, practitioners, builders and developers have either neglected or treated as secondary the relationship between human behavior and/or activities (as manifestation of the users’ cultural needs) and the spatial formof vernacular and transnational houses.In order to fill this gap, this paper constructs a conceptual framework based on cross-cultural studies to understand how migrants have influenced the spatial form of their transnational houses. More specifically, this framework provides a tool for the exploration of the ways in which first generation Italian migrants’ in Brisbane have influenced the spatial form, expressed though (a) its internal spatial distribution, as well as (b) the private immediate surroundings represented by the yards, of a specific typology of dwelling: the archetypal ‘house on a quarter-acre block’ built in post-World War II Brisbane.

2. Background

- The literature reviewed in this section is divided in three major sections.(1) In the first section I define key terms and terminology related to the physical field under investigation. (2) In the second section I review research studies undertaken on migrants’ housing experience in a host built environment revealing key-concepts and meanings which are embedded in the spatial form of their houses.(3) In the last section I present a conceptual framework for the exploration of the way Italian migrants influenced the spatial form of their houses in Brisbane. A review of the literature on the concepts listed above will facilitate an understanding of the factors influencing the spatial form of Italian migrants’ houses in Post WWII Brisbane.

2.1. Key Terms

- Key terms such as (1) built environment and built form, (2) vernacular and (3) transnational houses are recurrent throughout this paper. The meaning of these terms is defined in this section.Lawrence and Low define the built environment as an abstract and multidimensional concept which is employed to describe the products of human building activity and refers to any physical alteration of the natural environment through human construction (Lawrence & Low, 1990, p. 454).Built form applies to building types created to shelter, define and protect activity, included in the built environment (Rogers & Gumuchdjjan, 1996, p. 68). Built form includes houses and spaces that are defined and bounded but not necessarily enclosed, such as the uncovered areas in a compound, a plaza, or a street (Lawrence & Low, 1990, p. 454).The term ’vernacular architecture’ represents all buildings designed and built by their users within a bounded cultural and traditional context, in opposition to building exemplars created by formally trained architects (Tilley, Keane, Kuchler, Rowlands, & Spyder, 2006, p. 230). Furthermore, Rapoport (Rapoport, 1969, 1982a, 1982b, 1997, 2000) and Oliver (1997) point out that vernacular houses are built in a more spontaneous way in comparison to high style buildings designed in a professional environment. Notwithstanding, they stress that vernacular buildings are ignored in architectural theory, which is traditionally more concerned with investigating the purely context of monuments, temples and generally macro-scale buildings which emphasizes the skills and insights of visionary architects. In their view, while buildings belonging to the grand design tradition - such as macro-scale public buildings built in a professional context to impress the population - represents the culture of an elite, those of the folk tradition are ‘the direct and unself-conscious translation into physical form of a culture, its need and values-as well as desires, dreams and passion of a people’ (Rapoport, 1969, p. 2) and therefore are much more closely related to the culture as a way of life of the majority. Rapoport emphasizes the relationship between vernacular houses and culture as a way of life, in a context where those who create the built form have a common cultural framework with those who occupy and use the built form. This suggests that Rapoport’s theory, applicable to a vernacular architectural context, where the resultant built forms are designed and built by the users of the built form who share a particular cultural frame, can also be applied when a migrating cultural group is involved in the creation of its own living environment while cohabiting under a different dominant framework (Miller, 1994, p. 321). As a result, Rapoport defines vernacular houses built by migrants’ in a host country as transnational houses. He also highlights that trans-national houses, representing the location of most of the interaction of the members of migrant-families, adopt or change local vernacular built forms to accommodate migrants’ cultural needs and to respond to migrants’ cultural frame. Therefore, as Rapoport stresses, the form of trans-national houses can also be considered a physical manifestation of the cultural needs of the users (Rapoport, 2000, p. 129).

2.2. Meanings Embedded in the Spatial Form of Transnational Houses

- Rapport and Dawson (Rapport & Dawson, 1998) stress that the vernacular house is a mobile habitat which is subject to change and it cannot be perceived as a fixed physical structure. Also, argues that the users tend to distribute the domestic space to perform activities which are developed during the childhood.The use of space is an integral part of every human being’s daily life. Every day, we make subliminal and conscious decisions concerning the occasions at which a diverse range of activities will be performed. Such decisions are based on the spatial patterning that is developed in childhood through socialisation (Kent, 1984, p. 1).These insights suggest that this perception of the house as a habitat opened to changes may strengthen migrants’ desire to build and distribute their own new houses in the host country according to their past housing experience, to enhance the feeling of familiarity. Therefore, the construction process is seen as a way to create a tangible linkage between migrants’ present dwelling and their desired past house. Inevitably the new transnational house built in the host built environment can become aplace of memory. In addition to this interpretation, Depres (1991), in her studies of trans-national houses, emphasises that cultural groups interpreted the house as a place of refuge - reminding migrants of their origins - and a place allowing migrants to go back to the traditional activities they used to perform before emigrating. Following these insights, I investigated the extent to which Italian migrants’ housing past experience have influenced the shape of their new houses in their host environment with the ultimate purpose of fulfilling the need of creating a place of refuge reminding migrants of their origins and allowing migrants to go back to the activities traditionally performed in previous spatial environments.

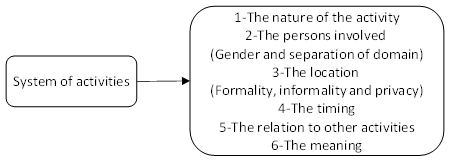

2.3. System and Setting of Activities

- Rapoport (Rapoport, 1969, 1982a, 1982b, 1997, 2000) and Kent (1997), who highlight the importance and the need to dismantle the concept of activities into its variables, identifies six components which, in their theories, represent the system of activities. They point out that the variability of the activity involves (1) the nature of the activity itself (what), (2) the persons involved or excluded (who), (3) the place where it is performed (where), (4) the order or sequence it occurs (when), (5) the association to other activities (how-including or excluding whom), and finally (6) the meaning of the activity (why). In order to understand the spatial form of the house, they stress the importance to study the systems of activities, because in his words ‘variability with lifestyle and ultimately culture goes up as one moves from the activity itself, through ways of carrying it out, the system of which it is part, and its meanings’ (Kent, 1990, p. 11).

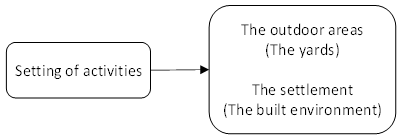

In addition to the definition of the system of activity, Rapoport and Kent highlight the importance to look at a wider spatial context to which the activity system of the occupants is linked: the settings of the activity. For example, they discuss how a common activity such as cooking, which is the transformation of raw food into cooked, can be related to the cultivation of vegetables or fruit which is an activity often performed in the outdoor area, the garden. Therefore, they point out that the settings of activities might include outdoor-garden areas. Rapoport stresses that by setting it is meant not only the one at a micro-scale level explained above but also the one at a macro scale-level: the settlement. Furthermore Kent highlights that “the setting frequently provides the appropriate props for these behaviours and activities’ (Kent, 1990, p. 12). Therefore, these insights highlight the importance to investigate the configuration of the surrounding built environment, since the settlement can influence the way people carry out activities in a public context and as a result the distribution of domestic space, planned to create space for performing activities in a more private context.

In addition to the definition of the system of activity, Rapoport and Kent highlight the importance to look at a wider spatial context to which the activity system of the occupants is linked: the settings of the activity. For example, they discuss how a common activity such as cooking, which is the transformation of raw food into cooked, can be related to the cultivation of vegetables or fruit which is an activity often performed in the outdoor area, the garden. Therefore, they point out that the settings of activities might include outdoor-garden areas. Rapoport stresses that by setting it is meant not only the one at a micro-scale level explained above but also the one at a macro scale-level: the settlement. Furthermore Kent highlights that “the setting frequently provides the appropriate props for these behaviours and activities’ (Kent, 1990, p. 12). Therefore, these insights highlight the importance to investigate the configuration of the surrounding built environment, since the settlement can influence the way people carry out activities in a public context and as a result the distribution of domestic space, planned to create space for performing activities in a more private context.  This aspect is also emphasized by Putnam, who highlights that the way we design and build a macro-scale urban setting where communities reside can have an impact on the degree to which people are involved in those communities (neighborhoods). He stresses that it is not just the micro-scale level single house’s spatial configuration, but also the surrounding built environment, enhancing a sense of community, which can promote social interaction among the population (Putnam, 2000). Those tangible substances [that] count for most in the daily lives of people: namely good will, fellowship, sympathy, and social intercourse among the individuals and families who make up a social unit … The individual is helpless socially if left to himself … If he comes into contact with the neighbour, and they with other neighbours, there will be an accumulation of social capital, which may immediately satisfy his social needs and which may bear a social potentially sufficient to the substantial improvement of living conditions in the whole community (Putnam, 2000).Also, Smith and Bugni stress that the planning of a city have an impact on the way people live in the city in a similar way as the internal layout of a house, distribution, location and size of each room within the house have an impact on the way tenants live their lives (Smith & Bugni, 2003). Emphatically, the way the city and its sectors is planned has a deep impact on the way people use the city, live their daily lives and carry on their social activities. In addition, scholars argue that the way in which people use the settlement also affect the spatial form of the house: for example in some urban context the meeting space can be the house while in other urban context the meeting space can be a street or a plaza which is part of the urban settlement. For example Rapoport shows how in the domestic space is mainly used to sleep and store things, while most social activities take place outside the house within the public open spaces of the city. In particular, Rapoport points out a relevant distinction between Latin, Mediterranean towns where people use the settlement or the public town square area within the settlement for social activities purposes and Anglo-American cities where inhabitants use their house and backyard to entertain social interactions (Rapoport, 1969, 1982a, 1982b, 1997, 2000).This suggests that for a better understanding of the way the configuration of the house enhances social activities, the house cannot be studied in isolation from the settlement. It has to be explored as part of the whole macro-scale spatial system which relates the single house, the settlement and the way of life, because the spatial form of the house is not just affected by the way the users live in it and the range of social activities taking place in it, but also by the way such activities are performed in the whole built environment. Further to this, scholars reveal that physical factors, such a climate, can also influence or determine the form of the house. As Rapoport highlights, in the climatic determinist perspective of a few architectural theorists, the form of the house is determined by the need for shelter and to protect the users from the natural environmental conditions. Therefore, in their view the form of the house is simply determined by climatic factors, because the house can shelter human beings against the extreme conditions of the climate. On the other hand, Rapoport points out that many forms of the house have been developed within the same climatic zones and, therefore, the form of the house is more closely related to cultural factors than to climate. In the same climatic zone there is indeed a great variety of house types. As Rapoport also highlights, elaborate dwellings are discovered in climatic areas where the basic need for shelter is minimal. He also points out that in some cases the way of life can lead to anticlimactic solutions, because the dwelling is more related to economic activities and the way of life than climate. For example, he highlights the fact that a group of Europeans in live in European style dwellings, not accepting that they should live in traditional courtyard houses which would be more comfortable. One of the reason Europeans were not able to live in those traditional houses was that they were comfortable with the European scale and arrangement of spaces, which were culturally unsuitable. These houses did not facilitate the performance of those activities which are influenced by cultural practices. This suggests that migrant groups tended to develop the form of their transnational houses in order to fulfill the need to perform specific activities which are influenced by an assimilated way of life or culture and not by climatic conditions. Therefore, it is also important to investigate the extent to which climatic conditions have influenced the spatial form of Italian houses in Brisbane.The literature shows that previous studies on the residential built form do not provide a deep understanding of the way and the extent to which the built environment influences the spatial form of transnational houses. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap. More specifically, this paper argues that the built environment in affected the way of life of first generation Italian migrants. In particular, it is argued that the form and structure of the typical Australian suburb in affected (1) the frequency and nature of social interactions among Italian migrants, (2) the spatial distribution of Italian migrants’ houses and, namely, the space allocations for rooms and areas utilized to enhance social activities.

This aspect is also emphasized by Putnam, who highlights that the way we design and build a macro-scale urban setting where communities reside can have an impact on the degree to which people are involved in those communities (neighborhoods). He stresses that it is not just the micro-scale level single house’s spatial configuration, but also the surrounding built environment, enhancing a sense of community, which can promote social interaction among the population (Putnam, 2000). Those tangible substances [that] count for most in the daily lives of people: namely good will, fellowship, sympathy, and social intercourse among the individuals and families who make up a social unit … The individual is helpless socially if left to himself … If he comes into contact with the neighbour, and they with other neighbours, there will be an accumulation of social capital, which may immediately satisfy his social needs and which may bear a social potentially sufficient to the substantial improvement of living conditions in the whole community (Putnam, 2000).Also, Smith and Bugni stress that the planning of a city have an impact on the way people live in the city in a similar way as the internal layout of a house, distribution, location and size of each room within the house have an impact on the way tenants live their lives (Smith & Bugni, 2003). Emphatically, the way the city and its sectors is planned has a deep impact on the way people use the city, live their daily lives and carry on their social activities. In addition, scholars argue that the way in which people use the settlement also affect the spatial form of the house: for example in some urban context the meeting space can be the house while in other urban context the meeting space can be a street or a plaza which is part of the urban settlement. For example Rapoport shows how in the domestic space is mainly used to sleep and store things, while most social activities take place outside the house within the public open spaces of the city. In particular, Rapoport points out a relevant distinction between Latin, Mediterranean towns where people use the settlement or the public town square area within the settlement for social activities purposes and Anglo-American cities where inhabitants use their house and backyard to entertain social interactions (Rapoport, 1969, 1982a, 1982b, 1997, 2000).This suggests that for a better understanding of the way the configuration of the house enhances social activities, the house cannot be studied in isolation from the settlement. It has to be explored as part of the whole macro-scale spatial system which relates the single house, the settlement and the way of life, because the spatial form of the house is not just affected by the way the users live in it and the range of social activities taking place in it, but also by the way such activities are performed in the whole built environment. Further to this, scholars reveal that physical factors, such a climate, can also influence or determine the form of the house. As Rapoport highlights, in the climatic determinist perspective of a few architectural theorists, the form of the house is determined by the need for shelter and to protect the users from the natural environmental conditions. Therefore, in their view the form of the house is simply determined by climatic factors, because the house can shelter human beings against the extreme conditions of the climate. On the other hand, Rapoport points out that many forms of the house have been developed within the same climatic zones and, therefore, the form of the house is more closely related to cultural factors than to climate. In the same climatic zone there is indeed a great variety of house types. As Rapoport also highlights, elaborate dwellings are discovered in climatic areas where the basic need for shelter is minimal. He also points out that in some cases the way of life can lead to anticlimactic solutions, because the dwelling is more related to economic activities and the way of life than climate. For example, he highlights the fact that a group of Europeans in live in European style dwellings, not accepting that they should live in traditional courtyard houses which would be more comfortable. One of the reason Europeans were not able to live in those traditional houses was that they were comfortable with the European scale and arrangement of spaces, which were culturally unsuitable. These houses did not facilitate the performance of those activities which are influenced by cultural practices. This suggests that migrant groups tended to develop the form of their transnational houses in order to fulfill the need to perform specific activities which are influenced by an assimilated way of life or culture and not by climatic conditions. Therefore, it is also important to investigate the extent to which climatic conditions have influenced the spatial form of Italian houses in Brisbane.The literature shows that previous studies on the residential built form do not provide a deep understanding of the way and the extent to which the built environment influences the spatial form of transnational houses. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap. More specifically, this paper argues that the built environment in affected the way of life of first generation Italian migrants. In particular, it is argued that the form and structure of the typical Australian suburb in affected (1) the frequency and nature of social interactions among Italian migrants, (2) the spatial distribution of Italian migrants’ houses and, namely, the space allocations for rooms and areas utilized to enhance social activities.3. Methodology and Methods

- This paper addresses the case of a specific typology of house: the dwelling built by Italian migrants on a quarter acre block in Brisbane in the post WWII period, where no research attempt has yet been made to investigate the way the users influenced the spatial form of their houses.In attempting to gain insights into the relationship between the spatial form of Italian migrants’ houses and the users’ cultural forces, the study employs a predominantly qualitative methodology. This is because insights into the cultural meaning that a material form has for individuals within a given social context can best be gleaned from the individuals themselves and by exploring the rich symbolic universe within which individuals exist. According to Clapman (2005), the cultural influences on dwellings need to be investigated through research based on qualitative methods, in order to capture and understand the way of life of occupants. Also, scholarsargue that the form of the house is difficult to understand outside the context of its cultural settings(Smith & Bugni, 2006).This study, then, is based on a symbolic interactionist perspective (Blumer, 1969). The case study design was selected to address the main question for this study. As de Vaus (2001, p. 223) highlighted, the use of a hypothesis building approach, starting with specific questions and expectations, explores actual cases in order to construct a hypothesis. As a result through this approach, the cases will be used to develop conceptual generalizations. Through an analysis of the case study it will be possible to explore and understand commonalities among cases. Therefore, a case study is considered a useful tool for generating hypothesis. In this study, the strategy of case study was selected because there is a need to produce context-based knowledge about the way Italian migrants influenced the spatial form of their houses in a host country.Further to this, as Merriam (1998, p. 38) emphasizes, case-studies can also be defined in terms of the overall intent of the study as ‘descriptive, interpretive and evaluative’. Because the ultimate purpose of this study is to explore the way Italian migrants influenced the spatial form of their houses in Brisbane, the most appropriate type of case-study for the current research is the ‘interpretive’. An interpretive case-study framework will provide an in-depth study of how Italian migrants influenced the built form and the nature of the forces behind. Johansson (2003, p. 5) states that the case study strategy enclosing cases has been developed not only within the social sciences but also in practice-oriented fields such as natural and built environment studies. Similarly, the investigation carried out in this current study is described as a single case-study, including multiple cases or subjects, because the use of a number of subjects allows for greater variation. This study uses a case-study strategy based on multiple cases to gather and analyze oral and visual data since individuals and physical artifacts form the cases to be investigated. Multiple cases were selected under the case study design because data from multiple cases can strengthen the findings (Yin, 2003, p. XV). In this case, the case-study allows the researcher to draw upon the lived experiences, thoughts and feelings of the potential participants in order to understand the meaning of living in a house built by Italian migrants in . It will also provide qualitative data to be gathered from the self-built artifacts and finally it gives Italians the opportunity to share their experiences and to speak about their contribution to the built environment of . In adopting a ‘qualitative’ methodology, this research study inevitably draws upon multiple qualitative research methods (Creswell, 2003, p. 181). One of the most significant aspects of case-study strategy is that varied methods are employed and combined, or triangulated, with the objective of exploring a case from different perspectives in order to ensure the validity of the case-study research (Denzin, 1978). This process, defined by Johansson as triangulation, or ‘the combination of different levels of techniques, methods, strategies, or theories, is the essence of case-study strategy’ (Johansson, 2003, p. 8). Therefore, to validate the findings within the current study, ‘triangulation’ from different sources (Yin, 2003, p. 159) is adopted. The methods employed in the study enable the researcher to collect (1) oral data, through digitally recorded focus groups and in-depth interviews, and (2) material or visual data through photo elicitation, site visits, field observations and visual materials including drawings and photographs (Creswell, 2003). An integration of methods collecting both oral and visual data is considered essential for the purpose of this study.

4. Data Collection

- The process of data collection started with the selection of Italian migrants, followed by the selection of the artifacts. The persons and the artifacts were selected according to specific criteria or limits. Interviewees were limited to migrants born in during the 1930s and 1940s, who are referred to in this study as ‘first-generation Italian migrants’. All selected first-generation migrants had migrated to in the 1950s and 1960s, that is, after WWII reconstruction in . As all interviewees were approximately 20–30 years old at the time of their arrival in Australia, It is assumed that people who lived in their homeland for several years and migrated as young adults were preferable because they had spent enough time in Italy to assimilate a way of life belonging to a cultural group. Additionally, social class is a ‘limit’ that must also be taken into account. Pierre Bourdieu (1992) argues that domestic behavior and cultural priorities differ according to the social class people belong to. Those selected for interview can be broadly classified as working class people: they constituted the majority of Italian immigrants migrating to Australia in the post–World War II period (Cresciani, 1985, p. 95). Accounting for the limits listed above, the case study included 20 Italian migrant couples and four self-built houses. The oral data and material evidence were concurrently collected at different stages.

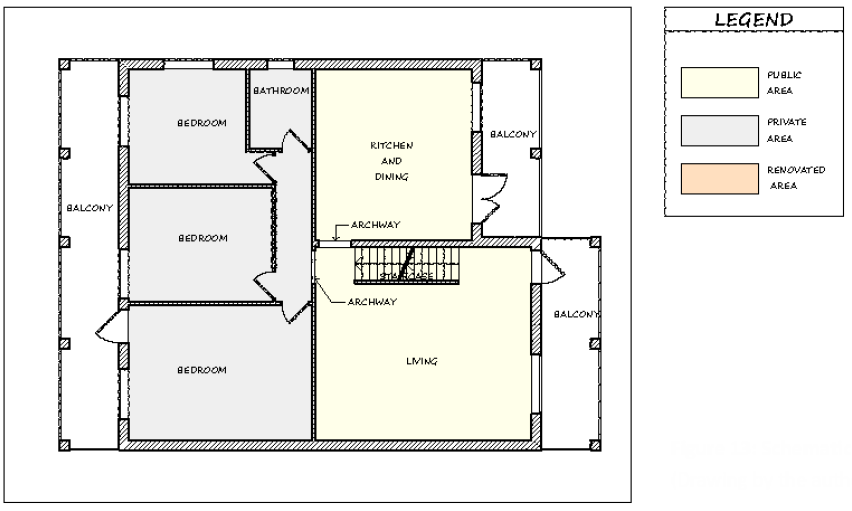

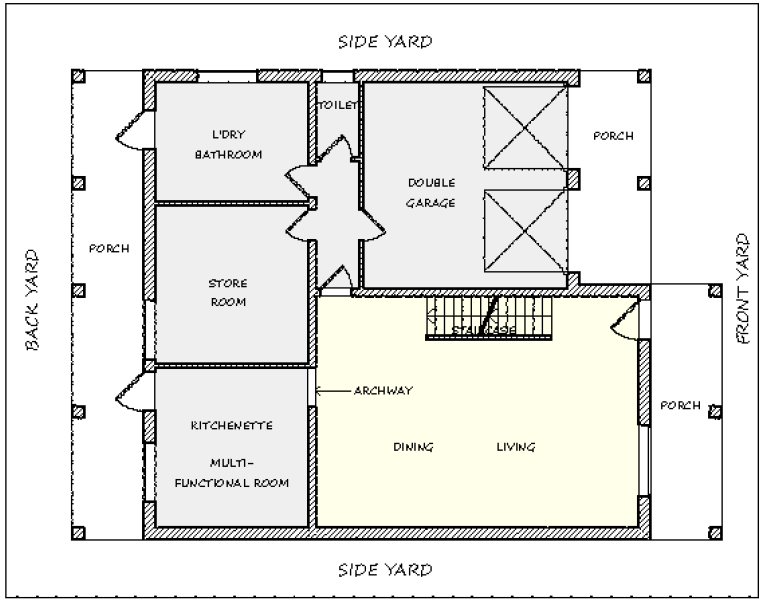

5. The Link between Migrants’ Cultural Needs, Urbanization Patterns and Italian Migrants’ Houses Spatial Form

- Italian migrants revealed that they built two-storey houses to allow having more space to be used by the family members’ to perform activities, in response to their specific needs. It was the influence of the internal mechanism and organization of the activities performed by family members the leading factor in decisions regarding the division and utilization of domestic space in Italian migrants’ houses built in post WWII Brisbane. The activities performed by family members could be subdivided into two main groups: (1) working and (2) social activities. In the following sections I will discuss how the need to perform these activities influenced the use of domestic space.

5.1. Working Activities

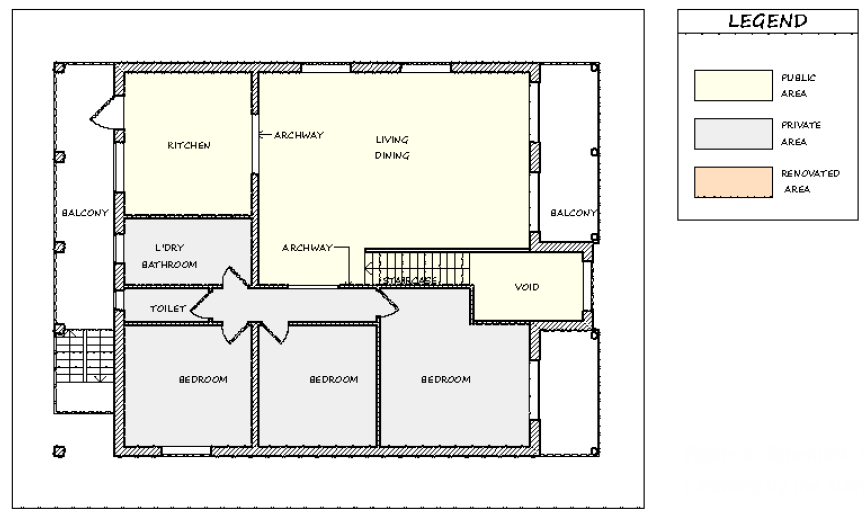

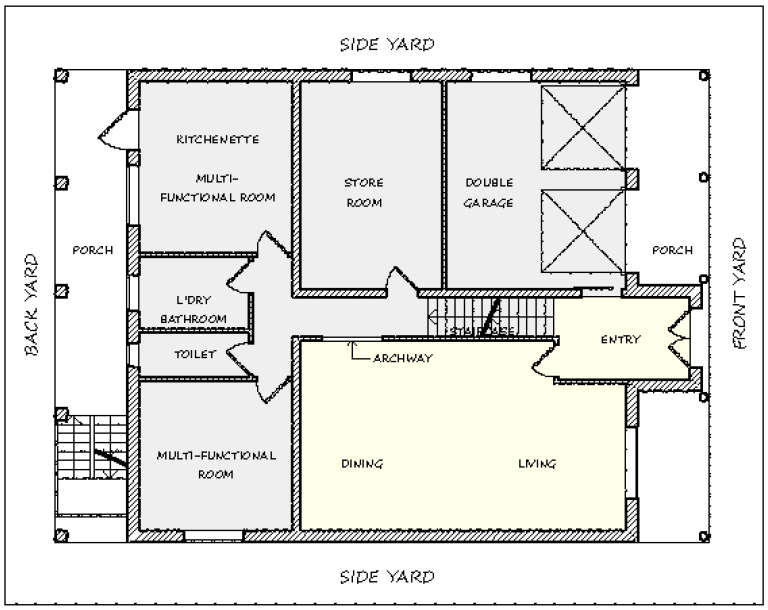

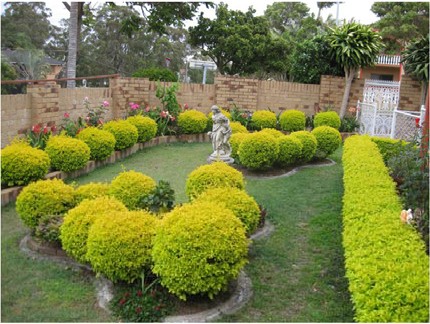

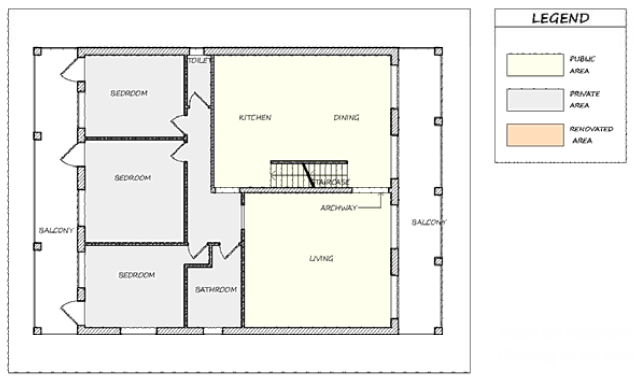

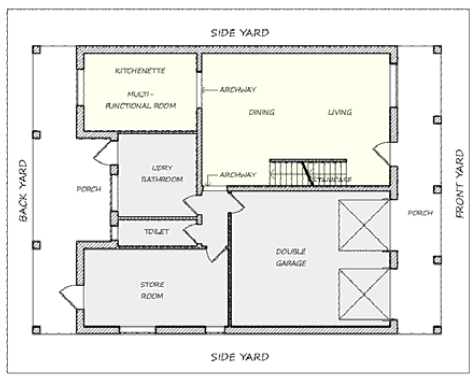

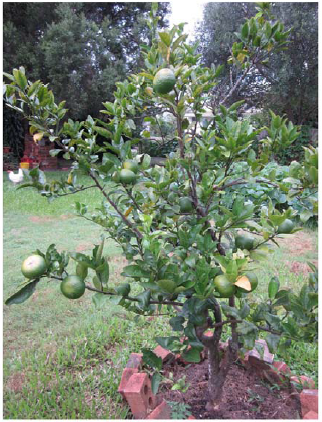

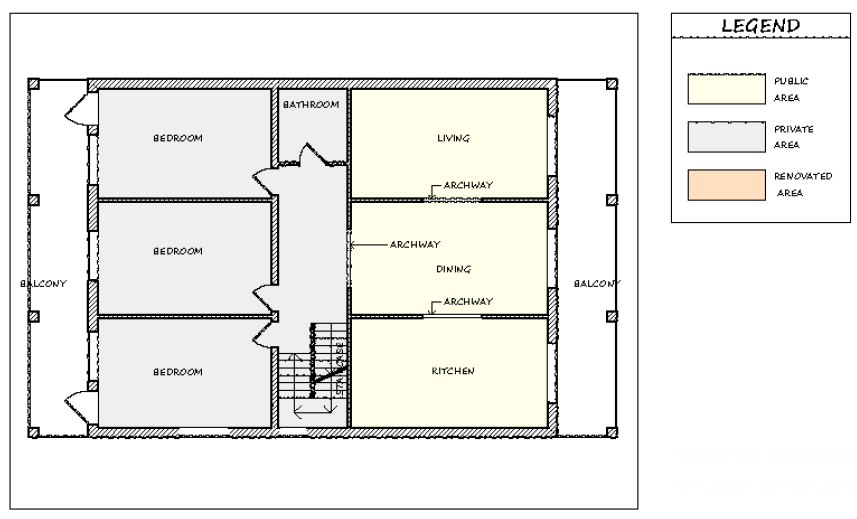

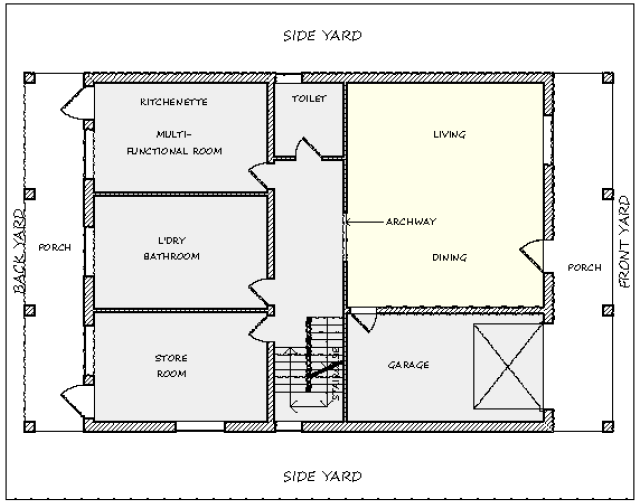

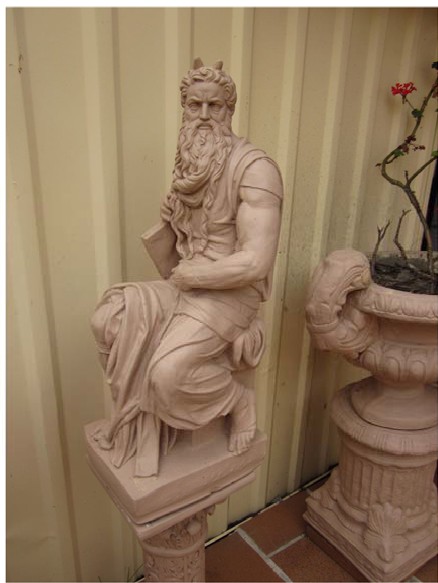

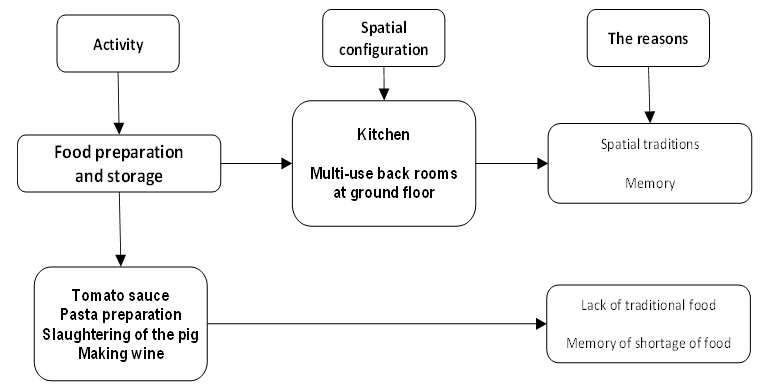

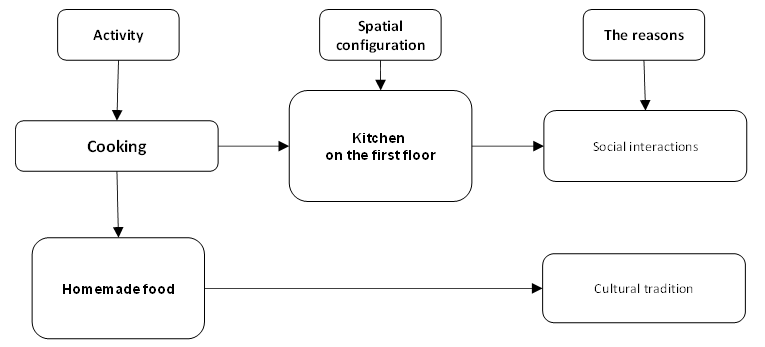

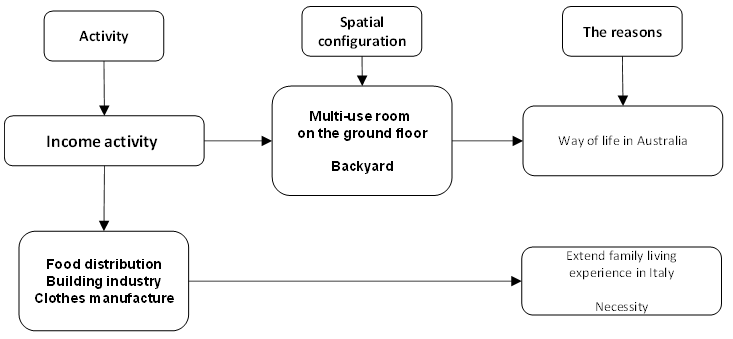

- The pattern showed that working activities performed within the domestic space could be further distinguished into two sub-groups: (a) domestic and (b) income activities. The findings revealed that most domestic activities within the house were in turn related to food preparation storage activities, such as making tomato sauce, pasta, gnocchi, lasagne, wine and other traditional food, but also the annual slaughtering of the pig and preparation of the smallgoods. This occurred since (a) after their arrival in Australia, Italian migrants could not find the types of food that they were accustomed to in Italy, (b) producing and storing food were domestic activities performed within the extended family back in Italy, (c) Italian migrants were influenced by the memory of scarcity of food back in Italy in the post WWII period.In all cases investigated it was shown that domestic activities related to food preparation and storage were carried out on a daily basis in the kitchenette and in the back multi-use rooms located at the ground floor, in proximity of the back yard (See Fig. 3-5-14-20-26). This was influenced by a spatial tradition assimilated through the extended family house experienced in . According to participants, the house of the extended family in Italy enclosed some multi-use rooms at the ground floor, in proximity of the kitchen, utilized for preparation and storage of food.In addition, the activity of food preparation was much related to the activity of the cultivation of vegetables (See Fig. 7-8-9-17-21-22-23-27-28-29). As a result, the outdoor back yard was used to plant agricultural species not for an aesthetic appeal but for cooking purposes. In turn, vegetables were exchanged with other Italians who shared the same habits of cultivating vegetables. Italian migrants wanted to create space within the outdoor area of the house to cultivate food in a more private context. This occurred because Italian migrants were influenced by their way of life in Italy: (a) even before leaving their native country, interviewees stated that besides producing and storing food within the extended family back in Italy, they also grew vegetables and fruit tree in the yards. All participants mentioned the difference in climate between Brisbane and Italy. Namely, it was highlighted that in response to the subtropical climate of Brisbane, which is hot and humid in summer and relatively warm in winter compared to Italy, Australians used to build verandas and pergolas in the back yard to facilitate outdoor social activities. On the other hand, it emerged how, in using the backyards for utilitarian purposes and not for social activities as facilitated by the climate in Brisbane, Italian migrants were influenced by the way of life learned within the extended family in Italy. In the extended family house in Italy, the garden or the domestic outdoor area was not used to entertain guests or for social interactions, but simply for growing vegetables and fruits. Italian migrants lived in Italy in rural areas where they were accustomed to using large areas of land for growing crops. Once in , the lot where the house was built was limited to approximately half an acre. Therefore, they tried to utilize as much land as possible to cultivate vegetables and fruits and not for social interaction, in spite of the fact that the subtropical climate facilitated outdoor social activities.If on one hand, the activity of food preparation and cooking was informally performed on a daily basis in the kitchenette located at the ground floor, on the other hand the activities of cooking was also performed in a second formal kitchen located at the first floor. This occurred especially on weekends and/or special events and it was related to social interactions. The kitchen, dining and living area at the first floor formed one open large space utilized mainly for formal events (See Fig. 2-4-13-19-25). The conformation of this space was partially influenced by the extended family house configuration where dining and kitchen area were also unified. In the case of Italian migrants in , they linked the living area to dining and kitchen area, creating one large open area. It was revealed that this was influenced by migrants’ way of life, namely by their need to enhance social interactions in a host environment.In comparison to the back yard, mainly cultivated for a more utilitarian purpose, namely to grow vegetables and fruits, the front garden was cultivated with plants and fruits trees for their aesthetic appeal. Also, while the back yard was used in a more private context, the front garden was easily visible and accessible by the public from the main street. The findings revealed that landscaping the front garden, namely cultivating it with distinctive plants and flowers, and also by showing some decorative objects, was a way to improve the overall look of the house and to express some individuality within the suburb. Also, it was interpreted as a way to show Italian migrants’ personal success (See Fig. 10-11-15-16-30- 31).The need to perform (b) income activities, which were mainly related to food distribution, building industry tools storage and clothes manufacture, also played a relevant role in the spatial distribution of the house. These activities were influenced by the activities migrants were acquainted with by living within the extended family in Italy and by the necessity to make a living in Australia. The findings reveal that these activities were mainly carried out on a daily basis in the multi-use rooms located at the back of the ground floor (See Fig. 3-14-20-26). Furthermore, participants revealed that working activities were subdivided by gender: the pattern shows that while wives spent much time in the kitchen for food preparation, storage and cooking, husbands were more involved in working-income activities.A site investigation of all houses investigated revealed that the living area in Italian houses is never a combination of covered space and open sky space, located at the back of the house, which allows for a public open area equipped with BBQ equipment and/or a pool to entertain guests. This occurs since the back yard of Italian houses is used for private working activities like gardening, cultivating vegetables and fruit trees, and the adjacent rooms at the ground floor are utilized for working activities. Therefore, the back yard is a private place for the family; it is not accessible without permission and it can be considered as a private extension of the back working rooms located at the ground floor.It was revealed that most of the activities listed above were influenced by a way of life assimilated in Italy through the past extended family living experience and also by necessity, or by a way of life learnt in Australia. This suggests that the domestic space was used for various working activities which were determined by the users’ way of life, which is an expression of culture; equally activities are expressions of culture, which in turn is translated into the houses spatial form through people way of life.

5.2. Social Activities and Urbanization Patterns

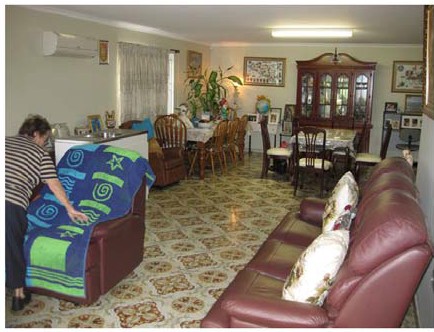

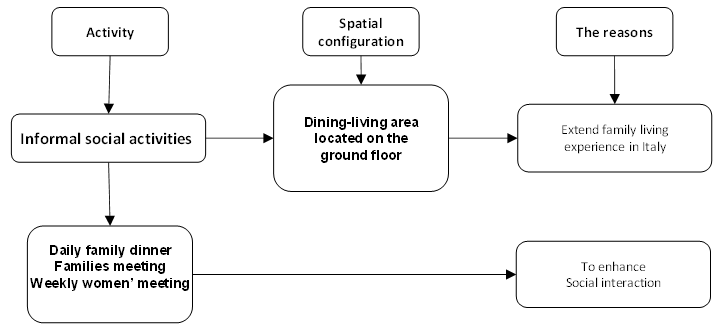

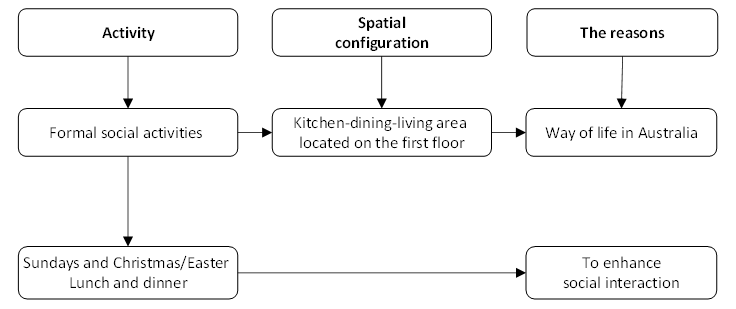

- Participants stated that after working in the sugar cane fields in North Queensland, many Italians moved to driven by the wish to live in a less isolated built environment where they would have more opportunities to socially interact among themselves and with locals. As a result, the house was distributed in order to allow social activities to be performed in a different context. More specifically, social activities were also subdivided into two categories: (a) informal and (b) formal social activities. The findings revealed that informal activities, such as the daily family dinner, the randomly family and women meeting, were performed in the living-dining area located at the ground floor and readily accessible through the front door of the house (See Fig. 6).On the other hand, formal activities, such as the Sundays and Christmas and Easter and general public holiday days lunch were carried out in the open area comprising living, dining and kitchen, located in the front area of the upper level (See Fig. 4)Participants highlighted that the internal layout in Italian migrants’ houses was purposively conceived to enhance their social interactions among family members, relatives, friends and neighbors. As shown, Italian migrants’ houses comprised two ‘daily areas’ utilized for social interactions: an area comprising living and dining rooms at the ground floor utilized for informal meetings, and an area comprising kitchen, living and dining rooms at the first floor utilized for formal meetings. The space to prepare food, cook and perform social activities is emphasized in Italian houses built in . This occurred because (1) traditionally Italian way of life has revolved around the preparation of food, a good glass of wine and the company of friends and family; (2) in Australia many migrants had no families with them and for those, new friends met in Australia became as intimate as family, taking the roles of aunts, uncles and grandparents. Coming together over the table in , was like creating a new family network and a sense of being Italian.The findings revealed another factor which contributed to allocate space for social activities: the host built environment. Interviewees stressed that (3) in the 1970s residential areas in Brisbane lacked of open public spaces, commonly used as meeting spaces, as town squares which were a urban element incorporated into the fabric of Italian cities. As a result, Italian migrants, perceiving that this lacking urban element contributed to deprive them of the possibility of socially interacting in the way they used to do back in Italy, allocated more space for social purposes within the house.

| Figure 2. Schematic first floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 3. Schematic ground floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 4. The formal living, dining kitchen area on the first floor. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 5. The kitchenette on the ground floor. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 6. The informal living, dining area on the ground floor. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 7. The backyard. Víttorío built a netted shed which combined a chicken coop and a vegetable garden. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 8. The backyard. The backyard, not commonly used for social activities, is used for the cultivation of vegetables and to store tools. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 9. The backyard. The backyard was also used as a garden nursery to cultivate decorative plants that would be moved to the front garden. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 10. The front garden. In the front garden Lina cultivated plants for decorative purposes. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 11. The front garden. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 13. Schematic first floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 14. Schematic ground floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 15. The front garden. The front garden was landscaped to show the family's success. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 17. The backyard. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 19. Schematic first floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 20. Schematic ground floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 21. The backyard. Zucchini, eggplants, fennel and tomatoes were cultivated in the backyard of the house. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 22. The backyard. A lemon tree cultivated in the backyard. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 23. The backyard. A coop located in the backyard which house ducks and turkeys as well as chickens. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 25. Schematic first floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 26. Schematic ground floor plan. (Drawing by the author) |

| Figure 27. The backyard. A tomato plant. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 28. The side garden. A lemon tree |

| Figure 29. The side garden. Olive trees |

| Figure 30. Decorative objects in the front garden. The statue ‘Moses’, a reproduction of Michelangelo Buonarrotti’s work adorning the front garden. (Photo by the author) |

| Figure 31. Decorative objects in the front garden. Fountains were located in the front garden of the house. (Photo by the author) |

| Diagram 1. Food preparation and storage activities |

| Diagram 2. The activity of cooking |

| Diagram 3. Income activities |

| Diagram 4. Informal social activities |

| Diagram 5. Formal social activities |

6. Conclusions

- Upon arrival in Australia, the author observed the form and size of those houses built by Italian migrants in Brisbane, but helacked the understanding of how the culture, as a way of life, of those for whom these buildings were constructed, influenced the spatial form of their houses. In this study, it was discovered that the spatial form of Italian migrants' houses is not just about large rooms and multi storey construction typology. The form shows more than a distinctive distributional space; it is the manifestation of a way of life of the people for whom it is built; it clearly expresses the history of these people and of their journey, from Italy to Australia.The findings, shown through the analysis of oral and visual data collected, revealed that the spatial form of Italian migrants’ transnational houses built in Brisbane was shaped in response to specific cultural needs influenced by a way of life which has adapted to the new host society. More specifically, it is shown that the spatial form of Italian houses was influenced by (1) socio-cultural factors, namely (a) working activities reminding family members of their origins and (b) social activities performed in the attempt to adjust to, to ‘tame’, and to make sense of, a radically different environment. These activities were influenced by culture, as a way of life, assimilated in the migrants’ native country and not as significantly by the physical factors, such as climatic conditions, encountered in the new environment. It was shown that climatic conditions in Brisbane actually had no influence over the spatial form of Italian migrants’ houses in Brisbane.In addition, the findings highlighted that (2) urbanization patterns in an alien built environment, namely the lack of public urban spaces like a town square traditionally utilized by Italian migrants in their native built environment for performing social activities, had an impact on the nature of social activities performed at a macro-scale level in Brisbane. The lack of public space in the host urban settlement combined with the need to establish a social network in a situation where integrative ties have been weakened by movement to a new location influenced the way Italian migrants conceived the internal spatial distribution of the house in : the house was configured in order to enhance social interactions. This insight means that migration to another land represents a fundamental dislocation of social activities and, in this regard, the spatial form of the house could be conceptualized as means of re-establishing and enhancing social interactions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML