-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2015; 5(1): 16-30

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20150501.03

Managing the Design Process in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review

Felix Atsrim1, Joseph Ignatius Teye Buertey1, Kwasi Boateng2

1Department of Built Environment, Pentecost University College, Accra, Ghana

2Ghana Airport Company Limited/ Lecturer, Pentecost University College, Accra, Ghana

Correspondence to: Joseph Ignatius Teye Buertey, Department of Built Environment, Pentecost University College, Accra, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Construction has existed since human existence. From the building of huts for shelter in the old ages to the construction of mega structures in recent times, the industry has developed over the years and has grown to become an enviable industry. It has transformed from a single person being the designer, builder and manager to a project environment where multiple organisations and professionals play a part. However this has not solved all the problems in the industry. One of the major concerns of the industry is the management of the design process. It is evident that unlike the olden days where buildings were built with the “trial and error” style of design as the construction went on, today’s industry engages designs before construction. The findings in this review have been based solely secondary data, with extensive review of literature that was available on the subject. The review is to generate more interest in this field since there is still more to be unfolded. This research reviewed some models of the design process, industry practice on design management and the role of project management in today’s industry. It however does not conclude on which of the models best suits the industry but suggests that the design process should not be managed with the same rigid tools and techniques of project management. It was concluded that the definition for design was contextual but shared certain key characteristics. The definitive part of the construction process needs a coherent management and coordination process for all stakeholders to enable the achievement if the key performance indicators of the project.

Keywords: Construction Industry, Creativity Design, Design management, Project management

Cite this paper: Felix Atsrim, Joseph Ignatius Teye Buertey, Kwasi Boateng, Managing the Design Process in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review, Architecture Research, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 16-30. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20150501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is generally held that “Between thought and object is design” [1]. The design process therefore is a vital stage in the realisation of any product and especially in the construction industry. The questions are; what is design? What are the processes involved? Can it be managed? If it can be managed, how different is it from project management? There are many more questions that have still not been fully answered when it comes to design because it is a difficult area to discuss. “Design is an inherently more complex process than construction: you do not know what the outcome is going to look like when you start; it’s creative; it’s iterative; yet on many projects we let those involved in the process, the designers, plan and manage the work themselves. The construction industry has changed markedly over the last twenty years and this has put an increasing pressure on design teams and design professionals to deliver” [2].The early days of construction involved the use of hands and simple tools to make huts and shelters for humans to live in [3]. This saw the involvement of all the inhabitants of an area in the construction process. By the 1800, the old ways of construction could barely meet the demands of the markets. This led to the formation of organisations in the construction industry. The industrial revolution had brought about the use of new materials such as concrete, steel and plastics and most of the building components were now being prefabricated [4]. The revolution as well brought about a structural means for eliminating or reducing immensely onsite activities in construction [5]. In the current construction industry, projects have become very complex and the standards for the measurement of the success of projects are ever being raised. The construction industry has had a lot of projects going over budget and with a lot of delays. Many of these problems are linked with the design management of the design process, which although is very important has still not had the maximum attention it requires. Until the design process is well understood, there will be very little emphasis on the management of the process. It is important to mention that there has however been a rise in understanding the relevance of design management to help achieve design within budget so as to ensure a successful delivery of project. The traditional methods, techniques and tools used to programme the construction process have not been successful in the management of the design process. Those rigid techniques do not work in the rather iterative process such as design. What is the way forward now? Thus the aim of this research was to create an understanding of the management of the design process in the construction industry, unravel the importance of the management of the design process, investigate the various stages of the design process, and to compare the project management with the management of design process. According to the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC), the construction industry has five major categories. They are: general construction and demolition, construction and repair of buildings, civil engineering, installation of fixtures and fittings and building completion. Previous research by [4] suggested at the time that this description does not conform to the current construction industry. Recently the industry has been redefined due to the changes that are occurring in this growing industry [5]. The UK National Statistics citing the SIC states that the industry includes general construction and demolition work, civil engineering, new construction work, and repair and maintenance [6]. The modern day construction industry uses the services of many specialist and organizations to produce a wide range of skills in creating products. This is as a result of the various disciplines involved in the industry. For this reason defining the boundaries of the construction industry does not appear an easy task.To be able to carry out these activities, new techniques such as construction management arose to help in organizing properly these constructions from beginning until they are delivered to the client. With time many more parties got involved in the industry requiring not only the management of the onsite activities but all aspects that had to do with the construction. This led to Project management. The current industry carries out construction as projects within defined procurement routes. The tradition of the master mason designing and leading the construction team has now changed to organizations designing and leading the team or just designing and the construction being carried out by a different organization.

2. Methodology

- Research methodology is postulated as the overall approach to the design process from the theoretical underpinning to the collection of data and analysis of data. The approach used in doing this work is broken down into desktop study through literature, compilation of ethnographic experience and field observations. A social science philosophy was adopted in this research, using qualitative methods due to the exploratory nature of the research and the subjective impact of the opinion of people during data gathering. The process involved information modeling, review of various research philosophies and methods that suggest that an interpretive social science methodology is the only one that could adequately address both the human influence and the technical aspect of design. Qualitative research can be described as a term used as overarching category, covering a wide range of approaches and methods found within different research disciplines. It is described variously as producing findings through research without statistical procedures. Qualitative research as subjective, exploratory and attitudinal in nature [7]. Comprehensively, it is a situated activity that locates the observer in the world; it consists of a set of interpretive, material practices that makes the world visible. These principles were explained to turn words into a series of representations including field notes, interviews, conversations, photographs, recordings, and memos to the self, which is naturalistic and an interpretive approach of the world. The above research relied deeply on qualitative research methodologies. As such information for this research was obtained solely from secondary sources with no field surveys.

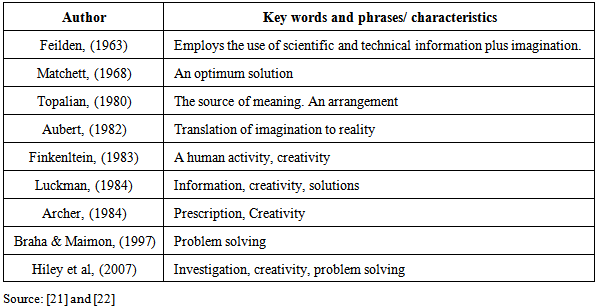

3. Project and Design Management

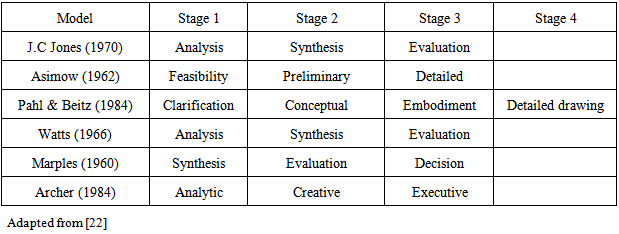

- A project is defined as:“A project is a complex, no routine, one-time effort limited by time budget recourses, and performance specifications designed to meet customer needs” [8]A definition by the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK) states that;“A project is a temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product or service” [9].It is important to indicate that the construction industry is complex. For the value of projects that are undertaken, it is important that the management techniques and tools applied help to achieve the best results. The application of the right project management techniques however does not guarantee project success. Based on ethnographic experience, many construction projects that have followed the necessary project management techniques and have been completed within time, cost and the qualities spelt out these techniques at the start of the projects. However, these projects turned out not to be successful since the overall benefits expected by cooperate organisations that funded them were not met during their operational stages. Many of these have been as a result of the users of the facilities not happy with the services these projects provided. This problem is mostly associated with design. When designs are done without considering the end user, the financial benefits expected by the clients can be reduced highly. The design process therefore is an important part of the construction of project [10]. On the other hand, if the design is taken seriously and managed properly taking into consideration all the stakeholders inputs, then there is an increase in possibility of all parties being happy with the end product hence the result is a successful project. The design process is a set of activities carried out to achieve the design objectives, thus meeting the product description in a specific context [11]. The design process is a focal point in any construction process. It is the design process that defines forms and specifies the product attributes and deliverables to be built. The design stage of a project was described by [12] as a stage where the primary project concept is translated into an expression of functional and technical requirements satisfying the client in an optimum and economic way. Despite its role on construction projects, little attention has been paid to the management of the design process [13].From observation and experience, many writers have expressed their views on the definition of design or what they judge design to be. Below are listed some of the views:“Engineering Design is the use of scientific principles, technical information and imagination in the definition of a mechanical structure, machine or system to perform pre-specified functions with the maximum economy and efficiency” [14]. “Design is a principal source from which structure and meanings are derived. Any arrangement of parts, forms, materials, colours, and so on, constitutes a design.” [15]“Design is the creative process which starts from a requirement and defines a contrivance or system and the methods of its realisation or implementation, so as to satisfy the requirement. It is a primary human activity and is central to engineering and the applied arts.” [16]“Design is a man’s first step towards the mastering of his environment . . . The process of design is the translation of information in the form of requirements, constraints, and experience into potential solutions which are considered by the designer to meet required performance characteristics . . . some creativity or originality must enter into the process for it to be called design”. [17]“Design involves a prescription or model, the intention of embodiment as hardware, and the presence of a creative step” [18]“Design as problem solving is a natural and the most ubiquitous of human activities. Design begins with the acknowledgement of needs and dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs…it is of central concern to all disciplines within the artificial sciences (engineering in the broadest sense).” [19]“The creative aspects of problem solving activities, in combination with investigative and other procedures, can be collectively described as being a design process” [20].A historical review by [21] as depicted in Table 1 shows the key words used by the various authors and their key findings with respect to their respective industrial affiliation. These factors could have affected their choice of keywords in the definitions. Taking account of these key words, design can be described in the manufacturing industry as: “The process of establishing requirements based on human needs, transforming them into performance specification and functions, which are then mapped and converted (subject to constraints) into design solutions (using creativity, scientific principles and technical knowledge) that can be economically manufactured and produced” [22].

|

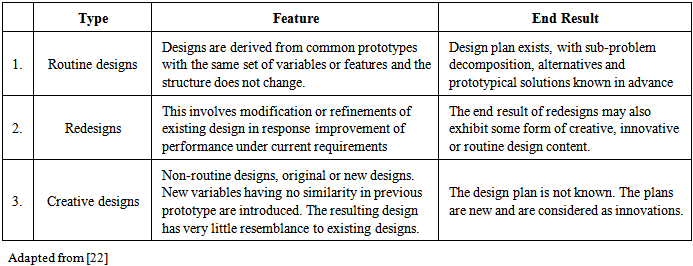

3.1. Types, Nature and Features of Design

- Design can be grouped into Product, Environmental, Information and Corporate identity designs. The product design includes; styling, ergonomics and manufacture of products. The environmental design includes architecture, interiors and landscape [23]. They further claim that the corporate identity mixes environmental and information design to portray the hallmark of an organisation. For the purpose of this research Product and Environmental designs are considered.Writers such as [23] and [24] have been cited in [22] have tried to define and group design into categories. Most of the classifications based on the literature of the above researchers have four categories. This may however be reduced to three by making the non- routine category as subset of creative designs. The table 2 shows the design problems that confront engineers and designers as described by the research of the above mentioned researchers.

|

|

4. The Design Process Described

- Various schools of thought have expressed how design is, might be or should be done. This undoubtedly has resulted in controversy [22]. This controversy may be as a result of the varying fields of practice of designers. The British design community expresses three schools of thought on how the design process should be [27].

4.1. Design: a Chaotic and Creative Process

- The first group believe that the design process should be chaotic and creative. This viewpoint is argued based on the claim that the design function is an art, and hence cannot be taught, which seems to imply that designers are born and not made. This claim of designers being born conflicts with many recent findings such as [22] who claim that designers need to apply their experience in the design process. It is true that design is creative but the process requires technical experience as well as training on decision making [28].

4.2. An Organised and Disciplined Process

- The second group believe that design should be organized and disciplined. [18] supports this claim, stating that: ‘Systematic methods come into their own, under one or more of three conditions: when the consequences of being wrong are grave; when the probability of being wrong is high (e.g. due to lack of prior experience); and/or when the number of interacting variables is so great that the breakeven point of man-hour cost versus machine-hour cost is passed [18]Archer’s statement suggests that the many activities involved in the design process as well as the level of uncertainty are reasons why the design process should be organised in a systematic manner. In this sense, the process is described as logical which involves checking and testing of anticipated solutions from rational and mathematical analysis with field experiments etc [22]. The design process could only be described as rational if the end goals of the process were fixed. Many designs start with no clear goals and the requirements by the stakeholders keep on changing throughout the process [29].

4.3. No Imposition of Design on Designer

- This third group argue that no design process should be imposed on a designer. This is to say that designers should be allowed to carry out the design process in a manner that is conducive to them. Designers can be described as creative, visionary, spatial and abstract thinking people with a high level of technical knowledge and experience [30]. This view conflicts with the first school of thought which claims that designers cannot be made but are born. Other researchers postulate that the design process is carried out for the personal satisfaction of the designer [28]. This statement supports the third group’s argument that no design process should be imposed on a designer. It is clear that the designer concerns himself with the requirements of his client but the personal satisfaction of the designer in terms of the process and the design is important. Some architects argue that planning a design process reduces the authentic creativity because the design activity depends on inspiration and perspiration [31].

4.4. Design: A complex Process

- The complexity of the design process features it as an open ended endeavour always with many solution options, and single “correct” answer. Many writers suggest that the nature of both the problem and the solution in the design process is what differentiates it from other types of problem solving. Design problems are usually more vaguely defined than analytical problems. Many clients usually cannot properly explain what they want and even in some cases they do not know what they want. Due to the varying interests that have to be satisfied, clients may not always be able to make clear their requirements [32]. Thus solving the design problems is often an iterative process: thus as the solution to a design problem evolves, there is a continual refinement of the design. Designers may discover at a stage that the solution being arrived at may be too expensive, unsafe or may not be feasible. Solutions are then modified until it meets your requirements. Interactive design brings the designer directly into the process by forcing him to be an integral part of it. This is necessitated in situations where: (a) the design problem is ill-defined, (b) there are insufficient analytical tools developed to enable quantitative analysis and (c) there is little or no experience available or associated with the design problem.

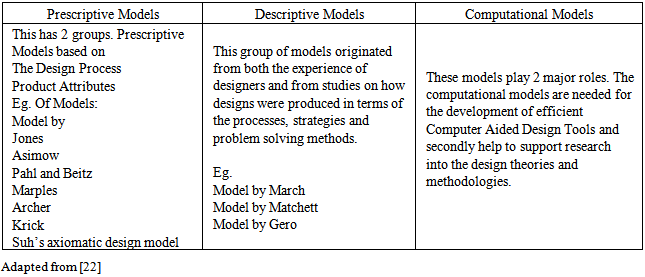

4.5. Models of the Design Process

- At the generic level, modelling is used in describing the processes by which design is undertaken. The design process is similar to problem solving and this goes through various stages which include: defining the problem and identifying the need, information collection, introduction of alternative solutions, choosing an optimal solution. Designing and constructing the prototype and evaluation [33].Since designers function in different parts of design space it is not surprising that there are many models which describe how design should be carried out as a result of varying definitions, methodologies, and personal preferences for design [34].“There is no single model that can furnish a perfect definition of the design process, design models provide us with powerful tools to explain and understand the design process” [19]. A critical study of the above prescriptive models in the table 4 and 5 suggests that some models are based completely on the design activities such as analysis, synthesis, evaluation and decision. Thus the review of models developed by [37] and [38] fall in this category. The Watts Model however describes the design process as consisting of the three processes of analysis, synthesis and evaluation, as proposed by Jones. These processes are performed cyclically from a more abstract level to a more concrete level (representing design phases). The model also shows the decision part as suggested by [39]. “The designer or design team during the design process frequently reiterates at one or more levels, and decisions are made along the way” [40].

|

|

4.6. Creativity and Innovation in the Design Process

- The design process has earlier in this literature been described as a creative problem solving activity. This means that only problem solving cannot be categorised as design or only creativity considered as design. It has been mentioned earlier that between idea and reality is design. If this is the case then what brings about that imagination of possible solutions to problems? Design can be seen as a complex activity that involves many decisions from the conception of an idea to the time a solution is selected out of the many other possible options. This will require some creativity since it will allow for multiple options.“There are many design decisions and design fields but there is a line of commonality in all of them; Creativity. The ability to visualise the non-existent and to reduce it from its abstract form into sketches and plans that can communicate a meaning for product development is the nature of design” [7].The involvement of many decision making processes and the open- ended nature of design requires creativity. This is because creative thinking process involves the critical study of reality with exploration of alternatives in creating innovative ideas [44]. Creativity is an important aspect of the design process but the question remains; what is creativity? Amabile, a famous writer in the field of creativity defines it as follows; “Creativity is the production of a novel and useful ideas in any domain.” [45]Is the use of novel and useful ideas suggesting that creativity is a thinking process? [46] suggests that creativity applies original thinking. One may agree with this statement that creativity involves thinking however there is no creativity seen if the thoughts are not expressed. Creativity is a captivating and stimulating aspect of human thinking. It has been defined as the ability to restructure old ideas to produce singular inventions [47]. Unlike a solution to a mathematical problem, the design problem solving requires creativity as a key element. The ill- structured and complex nature of design as stated already is the reason for the need for creativity because the design problems cannot only be solved with the application or algorithms or operators [48]. According to [49], cited from Dr. Noller [50], the mathematician’s work define creativity as; Creativity equals the function of attitude multiplied by knowledge, imagination and evaluation. Thus, Creativity = attitude x knowledge x imagination x evaluation If this is creativity, how then can all these components be managed in the design process? There are many people who believe that creativity cannot be taught but it is an intrinsic ability that can only be developed. However, according to the above mathematical expression by [50] the aspects that make creativity include at least two things that can be acquired by the process of learning; knowledge and evaluation. Although [28] agrees that there is the need for creativity in design, he argues that the complex nature of the design process demands also the experience of the professional designers who are not just technically inclined but have also been trained to make design decisions. The design process can be described as a decision-making process where the designer or the team is expected to make value judgement in choosing from many alternative design solutions. Although the criteria for choosing the best solution are based on the client’s requirements, the experience of the designer contributes greatly to the way this decision [22].This claims by [38] and [22] affirm the need for the technical knowledge, experience in the design activity and decision making as well as professionalism. The above mentioned points contradict the claim by the school of taught mentioned above which claims that designers are born and not made. That claim dwelt on the point that design was a creative and chaotic process. Considering the various definitions of design above, it can be said that creativity can be realised through experience and training and therefore design in this context cannot be considered as art. For the purpose of this review, the statement by [30] about designers is accepted as the best description of a designer.“Designers can be described as creative, visionary, spatial and abstract thinking people with a high level of technical knowledge and experience”.The above definition of the designer suggests that [30] see design as an act that involves a high level of technical knowledge and experience with spatial and abstract thinking, creativity and vision. There still appears some confusion here. Where? [30] see creativity as a separate attribute from vision and technical knowledge. This view is also supported by the findings of [51], who state that;“Apart from knowledge and expertise, design problems require creativity. Creative thinking enables one to perceive a problem from unorthodox and innovative perspectives”.However, knowledge can be held as an attribute of creativity. There have been searches into the design process, design solutions and designers’ personalities but there is limited knowledge on how designers assess design creativity. There is therefore the need for more research into the evaluation of creativity in the design problem solving [50]. Creative acts involve many characteristics of which results in originality utilising rational and intuitive processes [52]. It is not ideal to still think of creativity as an attribute that only a few have but it is necessary to realise that all humans creative capabilities and that this quality can be stirred up with proper guidance [53].

5. Managing the Design Process

- “Design Management is becoming increasingly recognised as critical to the success of complex construction projects. However, the role of the Design Manager is poorly defined and Design Management is a discipline without robust terms of reference” [54]In spite of the above stated claim, there does not appear to be one widely accepted view of what design management is. There is somewhat a staggered implementation of design management in the UK [55]. This therefore makes it difficult to discuss the management of the design process holistically but leaves room for some discussions on the management of some aspects of the design process. Some of aspects of the design process are therefore discussed below.

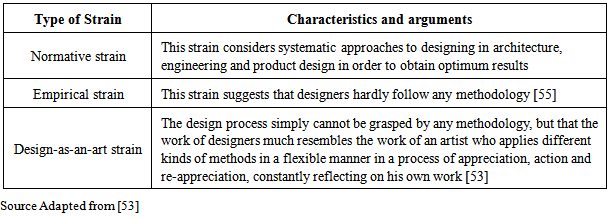

5.1. The Thinking Processes

- Before the management of the design process can be discussed and well understood, it is important to be aware of the thinking processes that have been found to be inherent in the design process. From tale 6, three thinking processes during the design process have been identified with reference to the findings of [53]. The normative strain, empirical strain and design-as-an-art strain are the thinking processes. Coupled with the many models of design, the difficulty in trying to define a standard model for the management of design process starts here. There are many models, different thinking processes, different stakeholders and an open ended problem to be solved. Systematic approaches to product design have been proposed by researchers in line with the normative strain. This supports the use of predetermined collaboration while empirical strain has emphasised the rare use of prescribed methodology according to the normative theories by designers. The design-as-an-art strain of research suggests that designers apply different kinds of methods in a flexible manner constantly reflecting on their own work and therefore there is no need for a predetermined collaboration. See table 6 below for the various attributes of the above strains created from [53], [54] and [55].

|

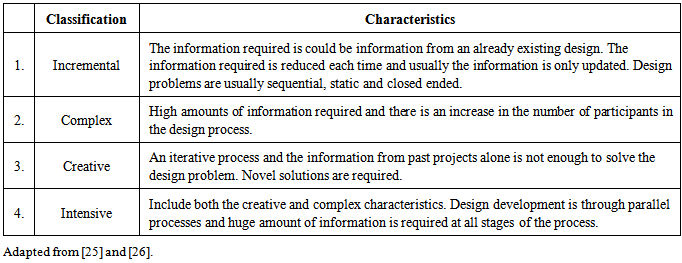

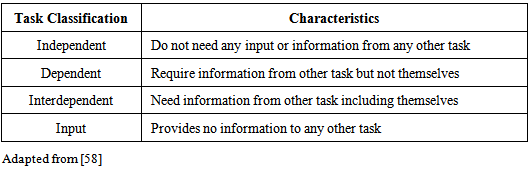

5.2. Managing Information (Design: A Process of Information Management)

- Engineering design processes involve highly creative and knowledge-intensive tasks that entail the exchange of wide information and excellent communication among distributed teams. The writers further state that,“In such dynamic settings, traditional information management systems fail to provide adequate support due to their inflexible data structures and hard-wired usage procedures, as well as their restricted ability to integrate process and product information” [56]This therefore suggests that there is the need to manage the information in the design process differently. A major problem in design process management is the existence of information cycles in the design plan. These cycles have to be managed well to enhance effective communication. There is the need to lay more emphasis on design as a conversation with the situation than just a technical rational process [57]. This conversation can only be relayed to the next person involved in the form of information that is easy to understand. There is therefore the need for the effective flow of information.The technical complexity of engineering designs is not the only reason that accounts for the difficulty in designing complex products. Management of iterative information flow during the design process is a key characteristics of engineering designs. Thus the complexity of managing the interaction of the different engineering disciplines and professionals gives additional challenge to the design process [58].There exists in engineering design information flow conflicts and this is dependent on the relationships among the design activities. It is difficult to manage this information due to the lack of formal management methods hence the unpredictability of the development cycle time. It is impossible to state that the transfer of information in the design processes follows a specific order but the interdependencies of some of the activities cannot be overlooked. The table 7 below shows the nature of the tasks that can be found in the design process.

|

5.3. Managing the Design Team

- “Design is an activity involving a wide spectrum of professionals in which products, services, graphics, interiors, and architecture all take part” [61].This statement shows that there are many players in the design process in this current industry. Design in modern days is done in a team as compared to the design that was mostly done by an individual. It is therefore important to place emphasis on managing the design team that may comprise of several people with different backgrounds, philosophies, style of work or approach to design. Team members may come from diverse cultures which may also have an impact on the process. It is important therefore that a team in this context is defined.“A team is a collection of individuals who are interdependent in their task, who share responsibilities for outcomes, who see themselves and who are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more social systems (eg. Business unit of a corporation) and who manage their relationship across boundaries” [62].Descriptive studies of design teams have shown that design cannot only be described as a complex technical process but also a complex social process [63]. The management of the collaboration and coordination among the members of the design team is of great importance. The essence of team work is recognised as important in achieving end goals. Teamwork is critically important in managing the projects because of the large amount of information of required in the design process.

5.4. Design Coordination

- [64] argue that the deficiency of coordination among designers on construction projects has contributed to lack of integration of design information hence the unnecessary time variations and design changes in their 2009 article “Methods of Coordination in Managing the Design Process of Refurbishment Projects.” They establish the importance of the management of the design process by placing emphasis on the relationship management of the design team in terms of the coordination of the participating individuals or groups in the design process. In terms of coordination among team members, two techniques namely, direct contact and meetings are considered to be appropriate coordination methods to be used in the design process [13]. It may be held that the use of the direct contact is required because of the iterative nature of the design process. Other reasons for the use of the direct contact are with regards to the various actors and the fragmentation of the construction system. [59] Describes the direct contact as the simplest one with minimal cost among the coordination methods. The direct contact is categorised into two forms; formal and informal direct contacts. Informal contact increases with the large number of participants and a high level of interdependency in the design process [65]. It can be explained that the formal contact is used to protect participants involved in the design process due to the complex and risky nature of today’s projects.The second method of coordination is also classified into two types; scheduled and unscheduled meetings supported by [66]. Meetings are identified as the medium used to increase interaction among the design team members. Scheduled meetings may thus be classified as meetings that are held at regular intervals to convey information about current work progress and recent designs [67] whereas unscheduled meetings are the meetings held urgently to resolve design problems. However due to the complex nature of the design process, some flexibility of the participants of the design team is required for effective unscheduled meetings. However, formal interaction that is scheduled meetings and direct formal contacts is considered predominant in the coordination during the design process of projects [13]. This finding however is a result of a research that was conducted on the design process for refurbishment projects. Could it be the same situation on an all new design projects?

5.5. The Designer

- The designer here is used to represent both a design team and an individual. The role of the client has been described above and it can be said that the solution to the problem posed by the client’s requirement is why the designer is employed. The designer in the construction industry always works with the brief. As stated earlier, the brief defines the problem, however many designers have mentioned that the briefs they get usually only suggests part of the problem and that the clients don not seem to understand what the designer needs in the brief to carry out his work [68]. The process therefore becomes a research which engages an investigation by the designer into the needs of the client, his expectations, on hand design practice, previous similar design solutions, past failures and successes [22]. This is the major challenge of designers. From the above premise, [68] states that “we never, ever get a brief from a client which we can start working on”. If this statement is true, then how do the designers get round the work? The designer in this situation has to find the problem and then solve it as well and this is why the designer’s work is not a “straight forward” problem solving process. It is about finding the problem and then solving it.“The designer may feel constrained by the manager’s insistence on commercial criteria; and there is a fine line between the designer educating the client or the final customer .... ignoring what the customer or client wants” [69]. This statement by [69] indicates that the designer must be able to make clear to the other stakeholders the best way forward in addressing the design problem. Limiting the design decision by the knowledge of the customer and client may prevent innovations. The design problems faced by designers are always interpreted quite differently by each designer and many designers always manipulate the problems to come out with multiple solutions. This is a reason for conflicts in the design team due the differences in opinions through perceptions and experiences of the team members.

5.6. Managing Conflicts in the Design Team

- The importance of the management of collaboration and coordination issues in the design team cannot be overemphasised though this does not necessarily remove conflicts. The many designers and different models of designs are major contributors to the existence of conflicts in the design teams during the design process. There also exists conflicts between the designer, the client and the end user and would be discussed in the stakeholder analysis. It is important to realise that conflicts do not always result in a negative outcome.Conflict was marked in the early days as a bad thing that should be avoided. It must be upheld that effective conflict management is not supposed to be regarded as a wasteful outbreak of incompatibilities, but a normal process whereby socially valuable differences register themselves for the enrichment of all concerned. Conflicts are therefore necessary and inevitable but can be managed [70]. The struggle of classes is defined as conflicts by Karl Marx, however for this review; conflict will be defined as “any disagreement due to the differences in opinions.” The management of conflicts during the design process is a very important aspect in design. If conflicts are not properly managed, they could result in disputes which take a longer time to solve and can that can affect the morale of the members of the design team thereby having a negative effect on the final design output.

5.7. Relevance of Conflicts to the Design Process

- It would be very difficult to put a design team together and expect a homogeneous group at once. Members of the design team may have different levels of understanding and this can result in the solution suggested by some members to be not well understood by the other members. Such a group may be classified as heterogeneous due to the conflicts but this could incite questions thus causing the group to revisit decisions to help in further analysis of the proposed solutions [53]. Careful analysis of solutions can lead to the evolution of new and important insights as a result of the challenging of opinions and conflicts. On complex problem solving tasks it has been found that heterogeneous teams have repeatedly been found to outperform homogenous teams. These conflicts are some of the reasons for the iterative nature of the design process. These conflicts can occur amongst the design team members, between the designers and the clients, and even on individual basis where the designer disagrees with his own initial solution. It is important that during the design process, the presence of conflicts is not seen as a bad action but considered as differences in opinions and then should be managed so as to arrive at the best possible solution. But the question still remains; is there one solution to a design question?

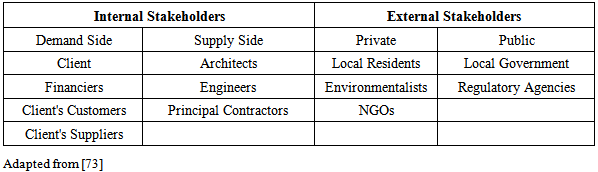

5.8. Stakeholders Analysis

- “The design stage of a project is the stage where the primary project concept is translated into an expression of functional and technical requirements satisfying the client in an optimum and economic way [71].”The above statement by Chan and seem to address the problem of only the client hence emphasising on the satisfaction of the client. This however does not truly refer to the current trends the industries. It can be said that design is a strategic tool and that a design is classified as a good one when what it produces recognises and adds the necessary knowledge of the wants of the customers, what can be produced efficiently and that which is in line with the products of the organisation [72].Products must meet standards that are acceptable to all stakeholders. This therefore makes the management of the design process more complex since the expectations of the various stakeholders in the final design should be met. For a project to be successful and well accepted by the stakeholders, that the management of the stakeholders should be taken into consideration during the design process since it is the design process that defines and shapes the final product. Project stakeholders are those actors which will incur a direct benefit or loss as a result of the project. [73] has described project stakeholders as being those who can influence the activities/final results of the project, whose lives or environment is positively or negatively affected by the project, and who receive direct and indirect benefit from it”. They are limited to five groups namely: client, consultant, contractor, end-users and the community. The table 8 above shows some stakeholders as described by [73].

|

5.9. The Client

- In the context of this literature, the client is defined as an individual, a group of people or organisations that contract the construction of facilities for their own use or for the use of a third party. Clients should have the key role as initiators of any project. “A client is a person or organization using the services of a lawyer or other professional person or company” [75].They are expected to be the “brain” behind the project and the steering force of processes for achieving results. The effectiveness of briefing by the client and the subsequent management of the relationship between the client and the design team have been spotted as one of the major factors that help to achieve a good design. It is important for the client to have a continuous participation and interaction with the design team as the design develops and there is the need for a level of trust of the designer by the client [28]. [4], in his book, “Construction UK, Introduction to the Industry” makes an analogy comparing two characteristics of the construction industry, the “bespoke” and “off the peg”. He explains that construction industry is very much a “bespoke” industry where clients define their requirements and then the designs are made and built to their specifications. There remain some instances where the customer chooses from already finished buildings which he may not have specified and this is “off the peg” [4]. Whichever way we look at this, there is always a client when it comes to the aspect of the design. In both cases someone would have asked for a design to be made and that person in this case is considered the client to the designer or design team with reference to the definition of [76] mentioned above. The role of the client in the design process is of much importance since the initial briefing is what informs the design. For this reason The Latham Report 2008 expressed the need for government to be influential in improving clients’ knowledge and practice of how to brief designers. There is always a difference between the requirements of the client and the possible solutions taking into account the technical and regulatory limitations. This becomes more complex when the client is not well informed on the range of options coupled with designers not actually understanding what the clients want. In most cases the client has very little idea of what he actually wants [68].

6. The RIBA Plan of Work

- Developed in 1963, the Plan of Work by the Royal Institute of British Architects is a well-recognized in the United Kingdom as a structure of building design and management of construction projects. It is a guide that covers management of activities from the appraisal of a project through to the post-construction. It has dwelt mainly on the professional responsibility of the architect (the designer) in the construction industry [35].

6.1. Stages of the RIBA Plan of Work

- Figure 5 describes the work stages involved in managing and designing building projects as well as the administration of the building contracts in the construction industry. This sequential work stages however vary depending on the procurement method chosen for the project delivery. The work stages are divided into 5 main components with 11 sub divisions. This review however is interested in the work stages A to F which fall under 3 of the 5 main stages; Preparation, Design and Pre-Construction. Although the RIBA describes the design process in sub activities C, D and E, it is important to analyse the design process from the Design brief (activity B) to the product information production (activity F). The design brief is included because the work of the design team is dependent on the design brief which states the instructions for the buildings. Let us now take a journey through the RIBA Plan of Work.

| Figure 5. The RIBA Plan of Work Adapted from [35] |

6.2. Why Manage the Design Process?

- Some interesting findings were made during review of the research by the Design innovation Group (DIG) that had been investigating the economic role of design for a period of more than a decade [21]. It was realised that the proper management of the design process was a major player in the success of organisations. This however was not limited to only the construction industry. It is clear that the quality of the design process has effects on developments. It does affect both the current and future environment [20]. For this reason it is important to manage the design process since the built environment is very much dependent on the design process. The design stage has been earlier described as the moment between thought and object. From this definition it is important that this phase of any project is managed so as to communicate the thought correctly into realisation. “There is a great deal of evidence to support the idea that while it is important for designers to be managers of the construction process, the management of the design process is inherently different from the act of design” [32]. It would be difficult to manage a design process if the design manager does not understand design. Although [32] make the above claim, the management of design is different from the process of design, it is important to state that the act of design must be understood before the process can be properly managed. This research has reviewed literature on the management of some aspects of the design process and has given reasons for why it is important. Its management is complex because unlike the construction stage of project the design stage faces an open-ended problem which has to be solved by selecting the best option. At the construction stage, there is no abstract problem to be solved. This problem would have been solved and the detailed design used as a guide in the construction stage of a project. Design is therefore complex and this complexity requires that the process is managed. The design process calls for mechanisms to monitor and control it. This view is stated by [23] as follows: “This complexity requires that the design process is effectively managed. Like any corporate activity design requires monitoring and control mechanisms. Standards and policies are necessary to ensure that design is consistent and maintains a recognised degree of quality. Effective management structures are needed to ensure that design meets company objectives and integrates appropriately with other corporate activities. Overall, a strategic approach to design at board level elevates design to an innovative process with a long-term horizon.”Twenty (20) years after Cooper and Press’ [23] statement, there has not been any single accepted structure for the management of the design process. It has been difficult to discuss the management of the methods used to design but much easier to tackle the issues of information management, stakeholders and the design team. Though the RIBA plan of Work does provide a framework for the process as it clearly divides it into stages at the end of each which there is a decision point or transfer to another stage, there has not been a conclusion on an appropriate management strategy for the design process however it can be said that the management structure will usually depend on the design environment [11].

6.3. Are Designs Projects?

- The literature reviewed in this work has shown that the design process plays a significant role in the construction industry. It has shown the changing trends in the construction industry and the rise of project management. The stages of projects have been mentioned in earlier in this research while the proposed stages of the design process have also been mentioned. The question that comes up here is how closely are the stages in the design process related to those proposed for projects. The design process has been described as iterative and this means that although these stages exist, they do not guarantee a sequential way of execution as can be seen in the project environment. This is why the critical path system can be used to estimate the project duration but cannot be relied upon in determining the design process duration. Is the design process a project? This is a difficult question to answer. Based on the literature that has been reviewed in this work, the answer to question may depend on the type of design. It has been mentioned earlier that some designs such as the routine designs need no originality. These designs use existing templates hence the cost, duration, quality as well as the results can be known ahead of the process. Such a design can be called a project since the characteristics established in that projects must have the following qualities.1. A well-known objective2. A defined life span with a start and an end3. Involves several professionals4. Typically brings about change or something unique and5. Has specific time, cost, and performance requirementsA project must have a well-defined objective but in the case of creative designs that require innovations, the problem may sometimes not be well defined hence the understanding of the problem can be the first step of the solution process. There is not a single solution to a design problem as stated by the findings of this research. Design problems require creative problem solving. Although some researchers have considered the design process as a project, it is believes that there is the need for further research into this area.

7. Economic and Social Benefits of Effective Design Management Process

- The benefits of properly managed designed process cannot be overemphasized. Some of the benefits are:1. It reduces the total duration for the design process 2. It enhances coordination and reduces conflicts and disagreement between the stakeholders and the design team3. It enhances proper scope planning, scope definition and scope control 4. It results in a reduction in change orders during project execution 5. Reduces the risk of schedule overruns during project execution6. It enhances a clear prediction of the project cost ahead of time and reduces the challenges of cost overrun7. It produces higher stakeholder satisfaction during the project execution and after completion 8. Enhance effective project risk management and risk control 9. Enables the development of a complete work break down structure and hence deliverables10. It enables a comprehensive quality management plan to be put in place for the construction process 11. It enhances effective project procurement process and integration management

8. Conclusions

- Management of design process in the construction process has exhaustively been discussed, reviewing the type, nature and features of design and discussing stakeholder involvement in the success of the design process. The following are the findings of this research:

8.1. Design Definition

- The literature has shown that the definition of design depends on the context. There are many definitions and some of them have been mentioned in this research. To arrive at an appropriate definition for the design process, contextual definition may be recommended. It can however be concluded from the review that there are certain characteristics which most of the definitions share. These are requirements, creativity, information and problem solving.

8.2. Summary on Models and Stages of Design

- There is not a single model that is accepted as the standard for the description and management of the design process. An objective of this research was to investigate some of the models of design and compare them. The review has shown that the creation of the models that exist were greatly influenced by the understanding, philosophies and area of specialty of the proponents. The RIBA Plan of Work although plays an important role, cannot be described as a model of the design process but rather a framework for managing construction processes. Although there are descriptions of stages of the design process, it can be said that these stages are not a linear process. The process is iterative and creative hence it is difficult to say that designers must follow specific and rigid processes. This can limit creativity. The design environment is what must be considered first before choosing the appropriate processes to follow.

8.3. The Importance of the Management of the Design Process

- The design process is the only process that defines what the outcome of a construction project will look like. It is the set of activities that are carried out at a stage on any project that can result in communicating the abstracts of construction into workable ideas. The importance of the management of design has in recent times received lots of attention signifying its relevance in the construction industry. Managing the design process effectively for the best outcome means that the project is halfway successful. Laxity and carelessness in the design result in porous and challenging designs. Nothing can be done without design in the construction industry and in this modern day industry, there is no chance for a trial and error construction style. The design process, the definitive part of the construction process is very important hence its management must be treated with equal importance. Rather than following strict methods to manage the design activities, the findings suggest that aspects such as information, conflicts and coordination among team members must be managed.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML