-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2014; 4(1): 20-34

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20140401.03

From Home Owners Perspective, “Ikun Concept” of Design in Benin, Nigeria: Some Like It Some Don’t

Ekhaese Eghosa Noel, Ediae Osahon James

Department of Architecture, School of Environmental Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ekhaese Eghosa Noel, Department of Architecture, School of Environmental Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Benin domestic courtyard design is as old as Benin kingdom (40 BC). The Edos built huge mud houses and the Oba (king) lived in large extended palace that could be to compare to Amsterdam, Netherlands. The Ikun concept of design (Oto-eghodo Design) is based on cultural considerations. The Edo socio-political structure determines categories of home owners, house size, organization and location across the City. The houses includes: house for commoners / poor, nobles, chiefs, diviners, chief priest, Enigies's palace, Oba's palace and shrines. The paper highlights the internal spaces quality and traditional courtyard house design in order to document the value and relevance from home owners’ perspective. The research employed qualitative and quantitative approaches (questionnaire, interviews guide, architectural plan documentation and observation). The result of findings has helped in shaping the orientation and understanding of all actors’ involved in house provision.

Keywords: Home Owners, Home Owners Perspective, Courtyard Design, User Preference and “Ikun Concept”

Cite this paper: Ekhaese Eghosa Noel, Ediae Osahon James, From Home Owners Perspective, “Ikun Concept” of Design in Benin, Nigeria: Some Like It Some Don’t, Architecture Research, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 20-34. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20140401.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Edo tropicalised architectural pattern was represented by the basic building unit which the Romans called "Atrium" and Edos calls it "Ikun” (Aisien, 2001). The Ikun concept design is a rectangular structure with several open spaces (i.e. Ikuns) surrounded by rooms. Often, family member sit on the corridors under the open space within the Oto-eghodo (Impluvium). The design consisted of several Ikuns strung together in series and each linked to the next by an internal corridor. However, the largest traditional compound in Benin (i.e. oba's palace) has two hundred and one (201) Atria and remains the best existing example of Ikun System of architecture in Benin today (Ekhaese, 2011). The family compounds houses consist of between two to seven Atria (Ikun) this includes the Forecourt Ikun which provides living spaces for male gender, Rear Ikun contained harem for women and children and the side Ikun which provided living spaces for household head. The study has identified different class of residential houses across Benin City from owners’ perspective based on Benin social - cultural - economic- political structure. It has engaged several approaches to examine Edo courtyard house design in order to determine its relevance and preference amongst home owners across the residential zones (Core, Intermediate, Sub-Urban and Planned Estate) in Benin, through physical observation and architectural plans documentation, social-political structure of Edo social system, interviews guide and attitudinal questions were raise and used from the questionnaires. All the results extracted from the various research instruments were used to determine the classes, relevance and preference of the design.

2. Impact of Socio-Cultural and Demographic Characteristics of Households on the Form and Organization Traditional Houses

- Socio-cultural characteristics are a systematic study of variation in social and cultural systems. Since society and culture are interdependent, therefore socio-cultural characteristics would be a more accepted term. According to Preston (2000) the term social characteristics is used within sociology and cultural characteristics applies to the anthropology. Rapoport and Hardie (2005) agreed that social and cultural variables are critical in defining the nature of relevant groups. To describe their lifestyle, values, preferences and nature of good/better settings for them, there must be a supportive environment to reduce/eliminate stress by modulating the social and cultural characteristics. They also found that certain cultural variables are useful in identifying a people and it is called ‘culture cores’. It is important to understand the interaction of such “core” with the components of a traditional house. In analysing socio-cultural characteristics, Rapoport et al (1990) outlined four basic ideals that need to be identified in a group: 1) the relevant critical core social units of the group and their role in the socio-cultural system, (Kin, age, ethnic religion, initiation), 2) the corresponding physical units at different scale, 3) the units of social integration/interaction for the group and other groups and 4) the institutions of the group (i.e. economic, recreational, rituals, governing and other activities). The vital step to take in designing, according to Rapoport and Hardies, is to identify the relationship between the culture core and social elements of the house. From the analysis so far, there is clear relationship between socio-culture and house types. For instance, in traditional houses, dwellings vary, and are required to vary along social hierarchy and where the house retains its domestic form it is due to the core cultural elements. Housing characteristics can be used as a measure of the socio-cultural status of household head, and its impacts on the social class of the homeowner.Demographic data has traditionally and broadly been exploited by researchers. Factors such as age, income, gender, and social class are regarded as reasonably good predictors of behavior and related activities (Pol 1991; Hansman and Schutjens 1993). Practitioners use demographic information very extensively and a large number of geo-demographic data bases are available. In academic research, the focus of inquiry has been on a specific behavior/specific demographic group. Gupta and Chintagunta (1994) examined the impact of demographic variables on segment membership whereas Kalyanam and Putler (1997) examined the effect of demographic variables on choice. And transportation mode choice models have also utilized the demographic finding. Concerning demographic groups, researchers have examined the family life cycle and its impact of house patterns. There has been extensive use of demographic data in research and researchers understand the impact of demographic characteristics on house (Mendes 1989; Pampel, Fost and O'Malley 1994). Demographic examination becomes more important as we approach the 21st century as change is taking place at a faster rate than is perceived (Pol and Thomas 1995). The key reason is that there are four demographic shifts happening at the same time. These four trends are: an aging but affluent population, the rise in working women households, increasing ethnic diversity, and decline of the middle class. The reason for identifying these four trends is their impact on traditional house. The trends might create discontinuity in practice (Bower and Christensen 1994; Christensen 1997).

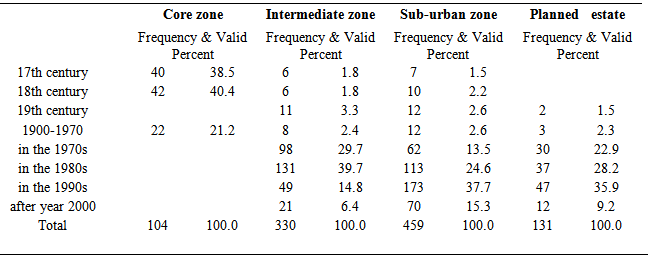

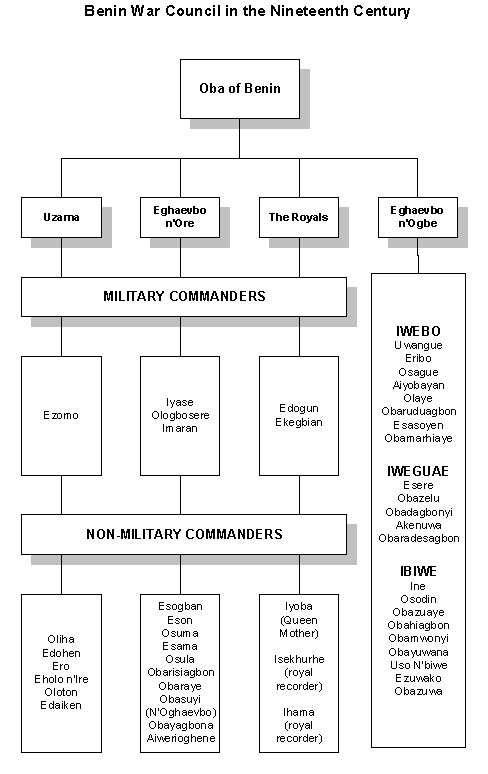

| Figure 1. Map of Benin city (Insert Edo State) Source: Atedhor, et al, (2011) |

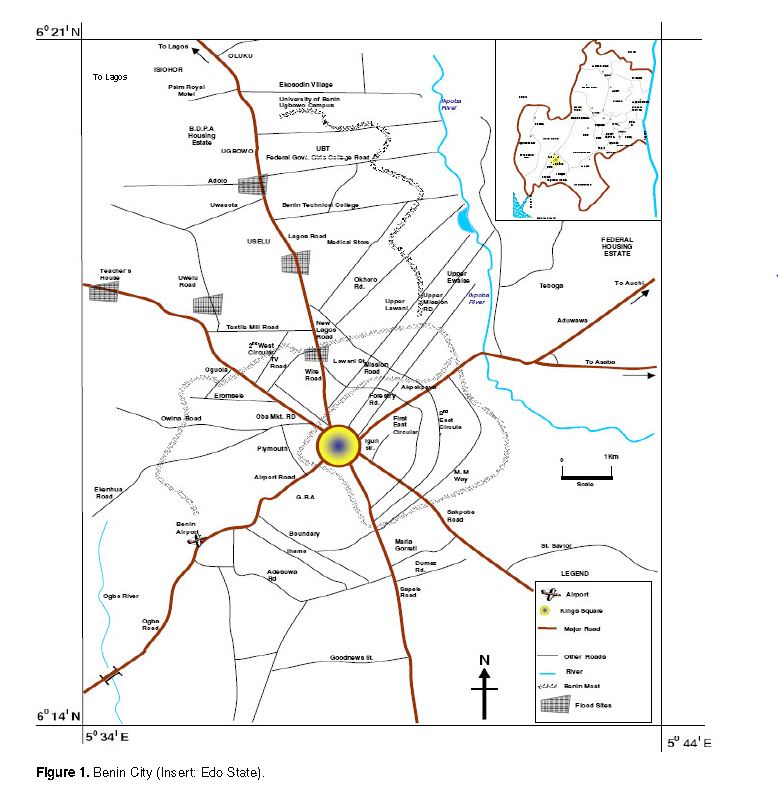

3. Study Area

- Benin City is located at latitude 06°19IE to 6°21IE and longitude 5°34IE to 5°44IE with an average elevation of 77.8 m above sea-level. Benin City is a pre-colonial city and is underlain by sedimentary formation of Miocene-Pleistocene -age often referred to as Benin formation The city is located in humid tropical rainforest belt of Nigeria with a population of 762,717 from 1991 national population census, but with a projected population of 1.3 million by 2010 at 2.9% growth rate. Benin City belongs to AF category of Koppen’s climatic classification and has witnessed rapid territorial expansion mainly due to rapid rural-urban migration because of its position as the capital of Edo State, mid-western part of Nigeria (Omoigui, 2005). According to USAID reports in 2002, Edo State was estimated to have a population of 2.86 million; and 64.47% live in Benin City (i.e. about 1,035,995 inhabitants), making it similar in size to Jamaica with a population of (2.74million) and bigger than Botswana, (1.6million) and Trinidad and Tobago, (1.1million). Edo State has eighteen (18) Local Government Areas. The Edos as people are cultural in their perspective and approach to life, with strong belief in traditions and various forms of worship which has set a spiritual and temporal authority for royal leadership in the State but it is fast being diluted by modern religious faiths. This occurrence has influenced Benin domestic architecture, so that contemporary architectural style is emerging along peripheries and new expansions of the City. The city was laid-out in regularly maintained massive-wide-straight streets/roads that begins and ends at the city core.

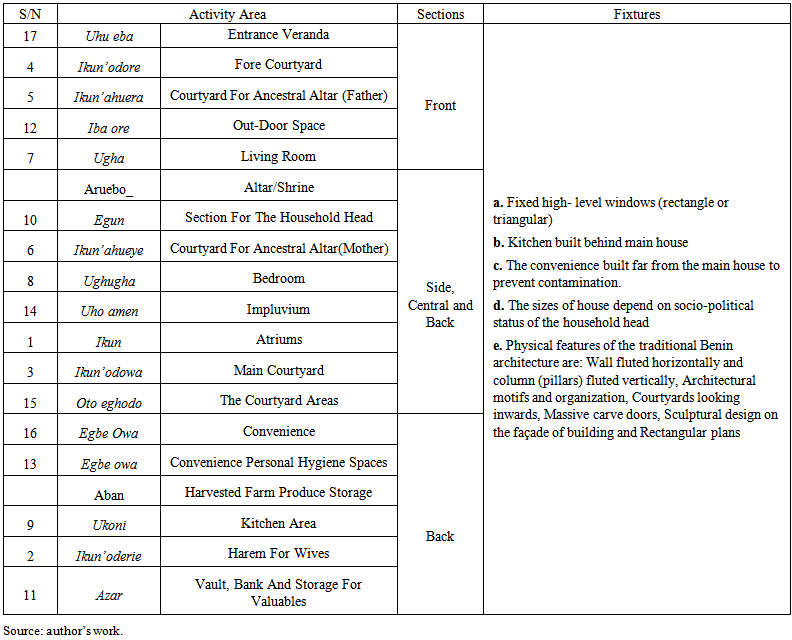

4. Identity and Social Structure of Edo Social Sysytem

- The Edos had an existing well-defined social structure, based on government of elders before the emergence of monarchical system. But developments which resulted in transformation of traditional values and customs may have endeared the Edos to a sense of history and tradition as a ways of life. The social system which developed in Benin City as shown is figure 2, has its origin in the historical consciousness that is sustainable (Osadolor, 2001). Before the seat of monarchy evolved, the settlement was a cluster of thirty-one villages with a sense of common identity based on history, tradition and beliefs of the society.

| Figure 2. Benin Council in Nineteen Century (2000) Source: Osadolor, (2001) |

5. Characteristics of an Edo Traditional Courtyard House

5.1. Pattern

- The traditional Benin courtyard house is an Ikun concept designed rectangular Rampart Earth structure. The sections includes Outer and Inner courts with water collection and drainage system impluvium which drains water underground through the central drain to River.

5.2. Heights

- The height of Benin courtyard house is measured in layers of mud-wattle-wall (a layer is equivalent to 2 regular sandcrete blocks arranged on top of each other). The house height is determined by home owner socio-political status. For instance, Poor/Commoner is 5 layers, Noble is 6 layers, Chiefs/chief priest/diviners is 7 layers, Oba is 7 and above.

5.3. Ornamentation and Material for Construction

- The materials for construction are locally sourced and method is through family/community effort. The materials includes; Olila – wood beam, Ere – wood column, Eken n’obar - Rammed-pact earth, Ebeeba - raffia/leaves, Iri – Twine.

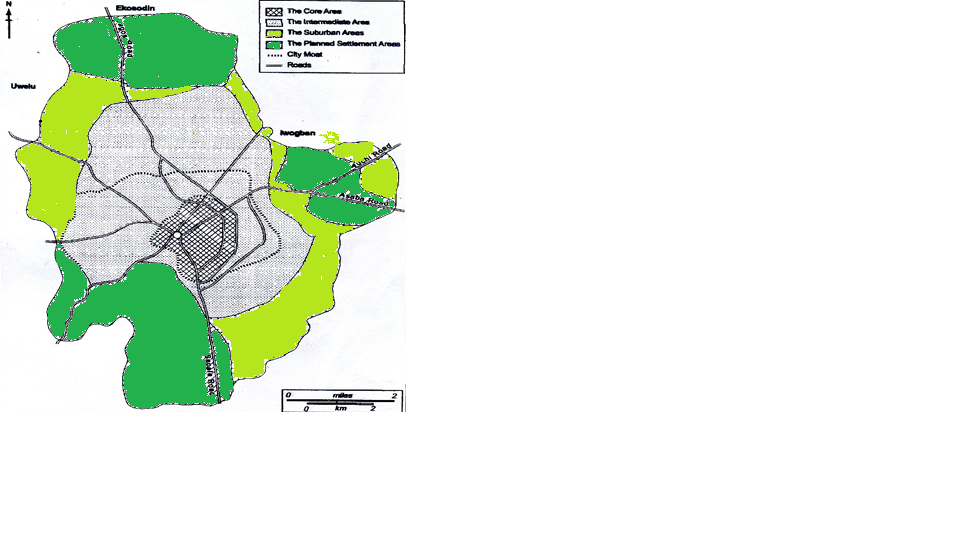

5.4. Sections/Activities Areas

- The Benin courtyard house is Family compound design for security, large family, festival, meeting and community activities, such that at the demise of home owner, wives, children and extended family lives in the house until they decide otherwise. Therefore the family compound house is built for generations. The Benin courtyard house is divided into sections like; Sleeping, receiving of visitors, storage, chambers, worship, kitchen, courtyard, birth delivery, Harem, playground, orchard, conveniences and owner’s apartment (with convenience, utility, rooms, visitors sitting and shrine). Each section is defined by a courtyard and categorized into activity areas like; Front, Back and Side Activity Area as shown in table 1.

| Table 1. The Activity Area in Benin Traditional Courtyard House |

6. Study Methodology

- This study is based on analysis of a relatively large sample of Ikun concept house-types in the core in other to determine its continuous relevance. To analyse home-owners choices and preferences of Ikun concept house over time in Benin, a field survey was conducted in Benin City and samples of architectural floor plans were collected, physical characteristics observed spaces organization analysed across the four residential zones as shown in figure 3. The Ikun concept houses were classified into categories base on the socio-cultural and socio-political structure in Benin, Nigeria. Therefore, the total residential houses across the four residential zones projected from 1991-2009 at growth rate of 2.9% was 52,850. 2% of 52,850 houses amounted to 1051houses, 100.4 houses in core zone, 353.6 houses in intermediate zone, 459 houses in suburban zone and 138 houses in planned estate. 1054 questionnaire were self-administered and duly completed by residents. But only the 21 attitudinal questions in section B of the questionnaire were used for this study. Furthermore 14 home owners drawn from cross section of chiefs, elders, landlord, dukes, university dons and professionals were interviewed.

| Figure 3. Map showing residential zone in Benin-city Source: Ekhaese, 2011 |

7. Findings, Discussions and Result

- Observation, documentation, sketches, photographs as well as deductions from interview guide indicated that there are different sizes of courtyard houses across the cross section of Benin, especially the city core and some of the city’s oldest part. The variable used for classification includes: Age of construction, Difference in space organisation and design, Ways of difference, Number of household, homeowner, Material for Construction and Home Owner Status (i.e. socio-political, socio-economic and socio-cultural). The analysis resulted in identifying several "Ikun concept" house-types.

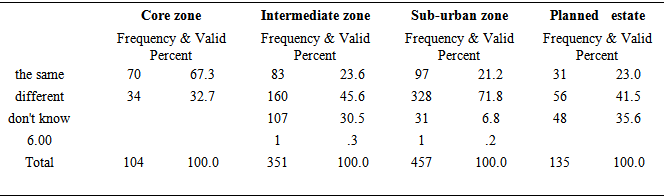

7.1. Age of Construction

- Ages of construction of Oto Eghodo house were analysed showing that houses built in core zone are mostly 17th and18th century and accounted for 79% while those intermediate and sub-urban area were built in 20th century accounting for about 87% and 78% respectively. However, houses in planned estates were built between 1970-2000 accounting for about 96%. This implies that most of the Ikun concept houses were found in core zone and preference of courtyard is mainly amongst the aged home-owners in core and old residential area of the city.

|

|

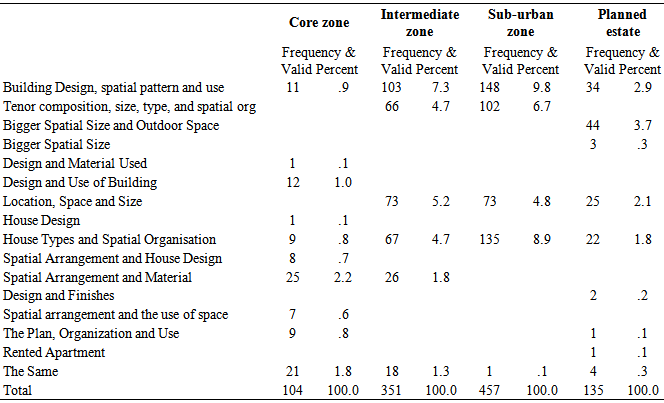

7.2. Difference in Space Organisation and Design between Former and Present Resident

- The difference in space, organization and design between former owner and present owner (inheritor) reveal that there are varied preferences amongst home-owners. In the core zone 70 houses out of 104 houses did not concoct any difference or change of space/design in their house and in intermediate zone, about 190 houses out of 351 houses that is 54.1%, above half of the home owners never engineers change in either space organization or house design showing that the preference of Ikun concept houses are amongst the aged also depends on the zone in the city.

7.3. Ways of Difference between Former and Present Residence

- From table 4: it shows that 11 houses in core, 163 in intermediate and 250 houses in suburban zone showed that building design, spatial pattern and use, tenure composition, house size, house type and space organization been repeated across the entire city revealing that similar house designs and pattern dots the city landscape. This reveals that the Oto Eghodo house design is the same but sizes vary depending on the home-owner status.

|

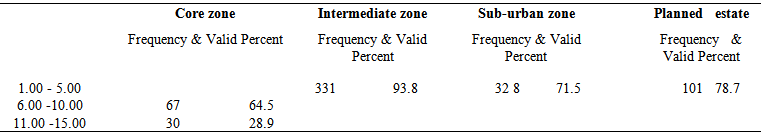

7.4. Number of Household in Respondent’s House

- The numbers of households occupying each house across the residential zones were presented. 78.7% of house-type in planned estates were occupied by between 1-2 persons, while 93.8% and 71.5% were occupied between 2-5 persons in intermediate and sub-urban zones respectively. 64.5% of houses in core zones were occupied by 6-10 persons and 28.9% were occupied by 11-15 persons. The greater percentages of large households were found in core area showing that Ikun concept houses are found in the core. It means that communal living is prevalent in core residential zone which is what Ikun concept house promotes. Therefore those home-owners who prefers the Ikun concept houses, encourages Africa family system.

7.5. The Builder/Owner of Respondent’s House

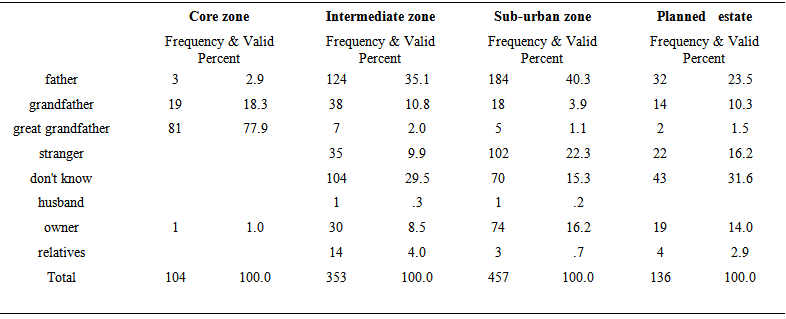

- The home builder/owner presented in table 6 revealed that 97% of houses in core residential zone were owned by grandfathers and great-grand father, 299 out of 353 houses in intermediate zone were owned by fathers/owners/ landlords amounting to 85%. While in sub-urban zone 430 out of 459 houses amounting to 94% were owned by fathers/owners/landlords, majority of houses in planned estate were owned by owners/strangers that amounted to 116 houses and 85%. This shows that home-owners in the city core, intermediate and sub-urban zones all inherited the houses, because the houses were originally built by their great-grand and grandfathers.

| Table 5. Number of household in respondents’ house |

| Table 6. The Builder/Owner of Respondent’s House |

- The summary of discussion so far has revealed that there are different house-types across the residential zones of the city. The ages, owners and number of household shows that the core has the oldest and largest houses in the city, houses in intermediate and sub-urban shows resemblance with each other but are slight different from core zone house-types. In planned estate, the houses are the newest, smallest and singled family. This reflects the preferences and choices of home-owners across the entire city.

8. Classification of Houses in Benin Bases on Owners Perspective (Oto Eghodo” Ikun Concept” of Design)

- The Edo traditional residential courtyard houses are of two categories: Palace Compound House and Family Compound House. Comparatively palace compound house which includes Oba’s palace, hereditary chief’s palace and non-hereditary chiefs’ palace are larger and have more courtyards than family compound house of nobles and commoners. The Oto Eghodo houses could be differentiated in their aspects of quality and complexity, but they have one thing in common which is a public and private area. However all the courtyard house-type described below fall under the two categories of residential houses except the shrine (Ogua) which is designed for celebration/ worship of deity.

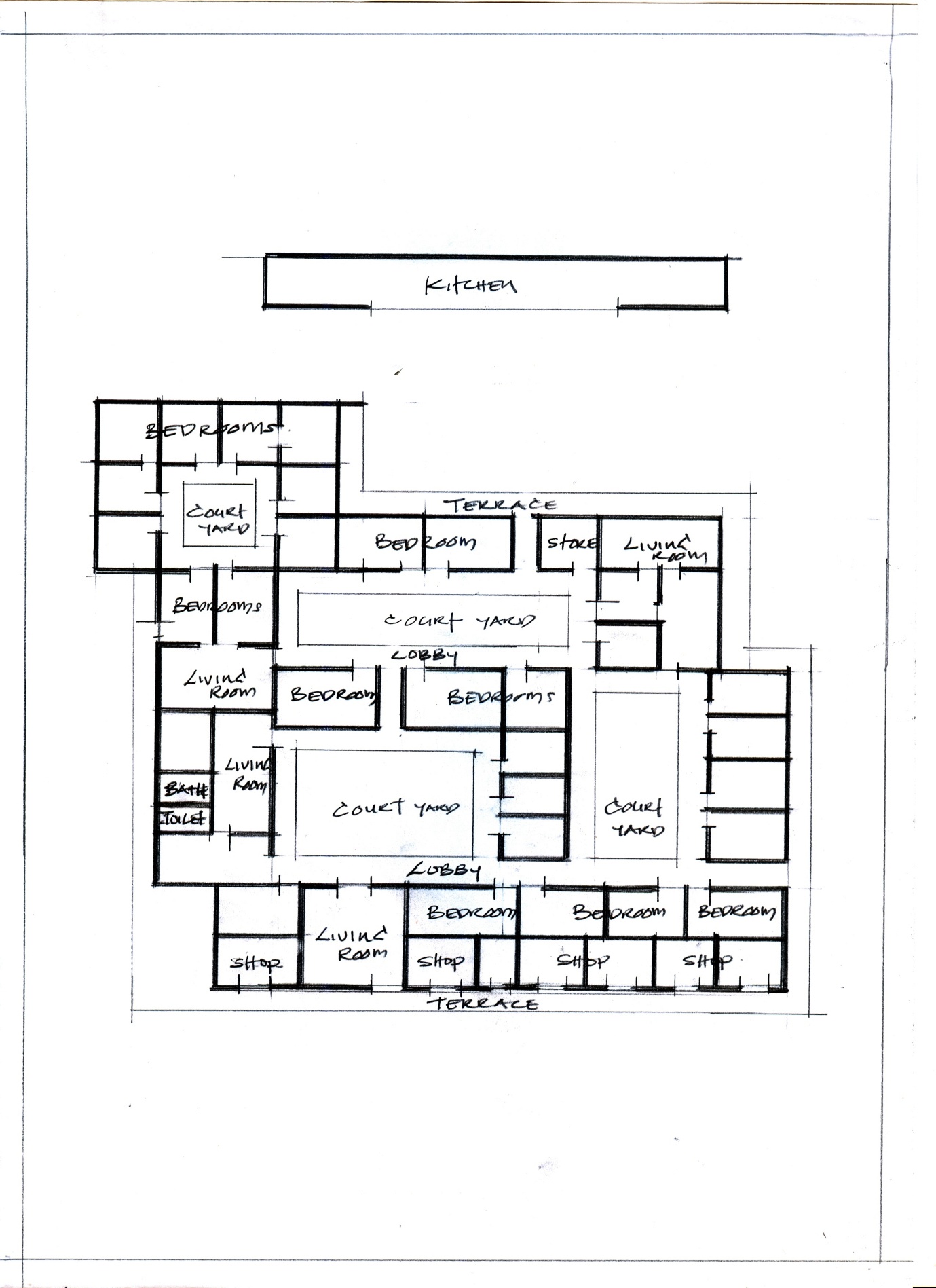

8.1. Owa’evien (House of Slaves)

- Owa’eveien has an outer veranda about 12-16ft long, leading to a corridor. The corridor connects the central courtyard where the family altar and all the other rooms are located. From the central courtyard there is an access leading to the backdoor section where the kitchen and convenient are located. The Owa’eviens is built of mud (laterite), rectangular in shape, and it is the smallest of all Ikun concept residential houses in Benin City. The design naturally is divided into; Front, side and back section.

| Figure 4. Floor Plan of House of the Slaves in Benin City |

| Figure 5. Floor Plan of the house of the commoners and poor In Benin City |

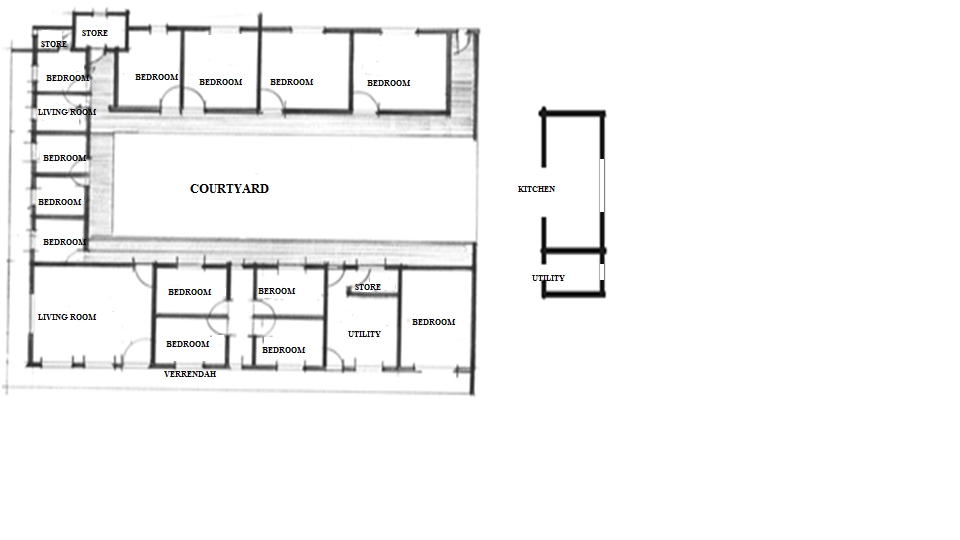

8.2. Owa’ogue, (House of Commoners/ Poor)

- The Owa’ogue a is box-shaped Ikun concept design with walls constructed of mud (laterite), like Owa’evien the design is divided into; Front, side and back section. It has an outer veranda leading to corridor that connects all other sections of the house. The corridor which has access to the main courtyard has two rooms on both sides. The courtyard is engaged for multiple activities like; worship, celebration, eating, receiving visitors, relaxation and moonlight tales. From the courtyard, a door leads to back section for backdoor activities like; cooking, using the conveniences, farm produce storage etc. The kitchen and convenience are always detached from the main house and parlour in front for entertaining visitor.

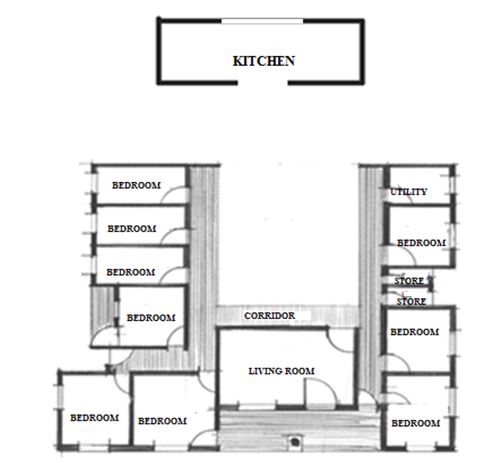

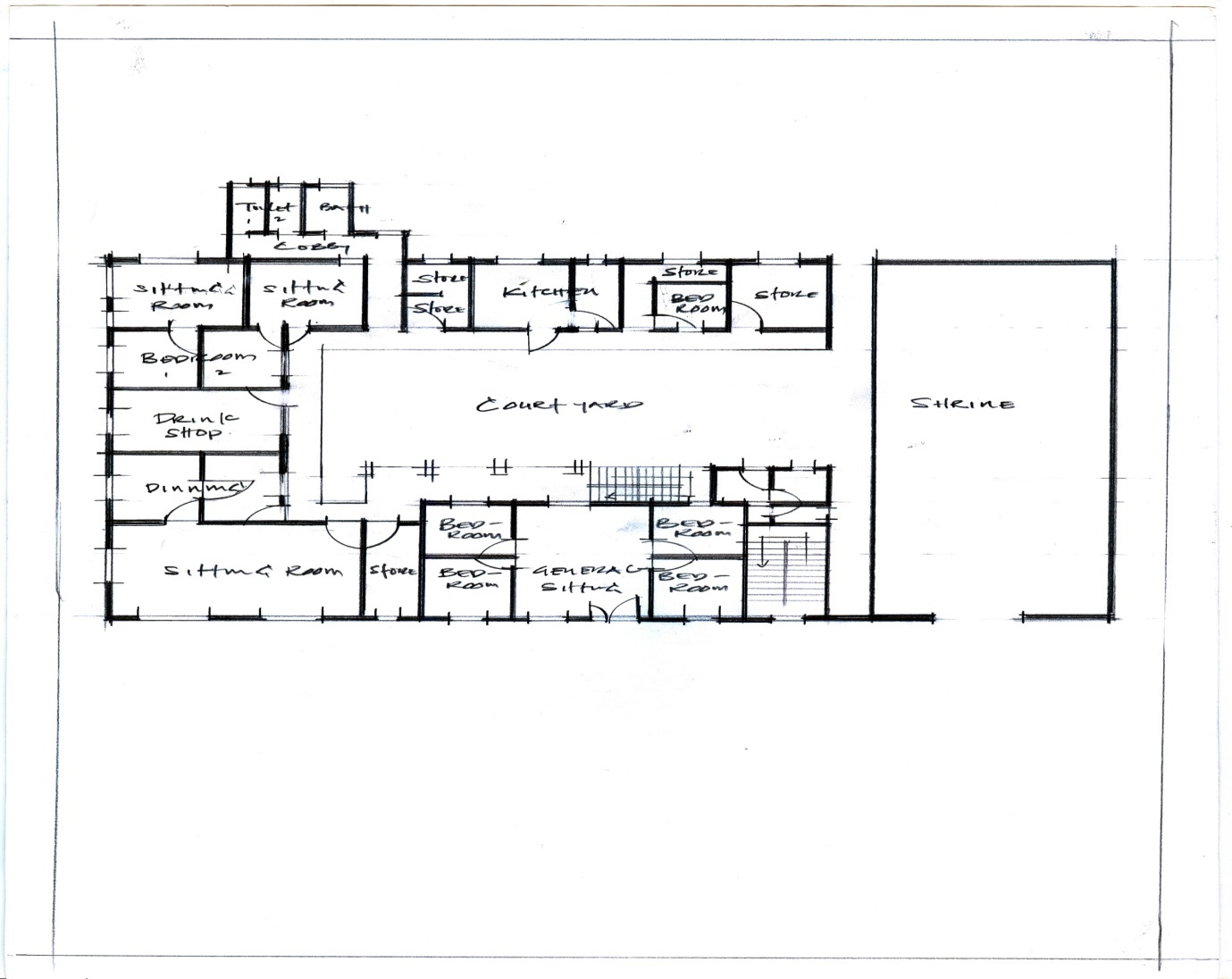

8.3. Owa’dafen (House of Nobles and Wealthy)

- The house of the noble/wealthy is construction through communal effort which is a reciprocal gesture. The Owa’dafen otherwise known as (Igieowa) has a length veranda in front connected to a corridor of about 14-21ft long, which has rooms and a living room on both sides. The rooms are for servants and male relatives. This corridor connects the fore courtyard known as Ikun n’aruerha where the ancestral altar is located. The courtyard leads to Ikun n’derie, i.e. Harem for wives towards the back section of the house. The harem is a longitudinal/parallel arrangement containing 5-7 rooms depending on the numbers of wives. Closely linked to wives harem is children harem with series of rooms around a corridor that leads to back section that is detached from the main house where kitchen and convenient are located. The Igieowa is an Ikun concept design with height of six (6) layers. It is a hollow structure with several opening (courtyard), typical of an Ikun concept and it is spread on a large expanse of land with three main sections; Front section (Ikun n’odore) for servants and male family member, encloses living room (Ugha), fore courtyard, shops etc. The side section (Egun) house owner apartment and back section consist of harem for wives, menstruation room, storage, kitchen, convenience. The flow in typical traditional Edo courtyard houses shows a movement from front corridor to fore courtyard and then to house owner section from there to harem for wives and straight to children harem and to kitchen, from there to the convenience at the back section far away from main house. The Ikun concept design is an organic design that allow proper ventilations, proper light.

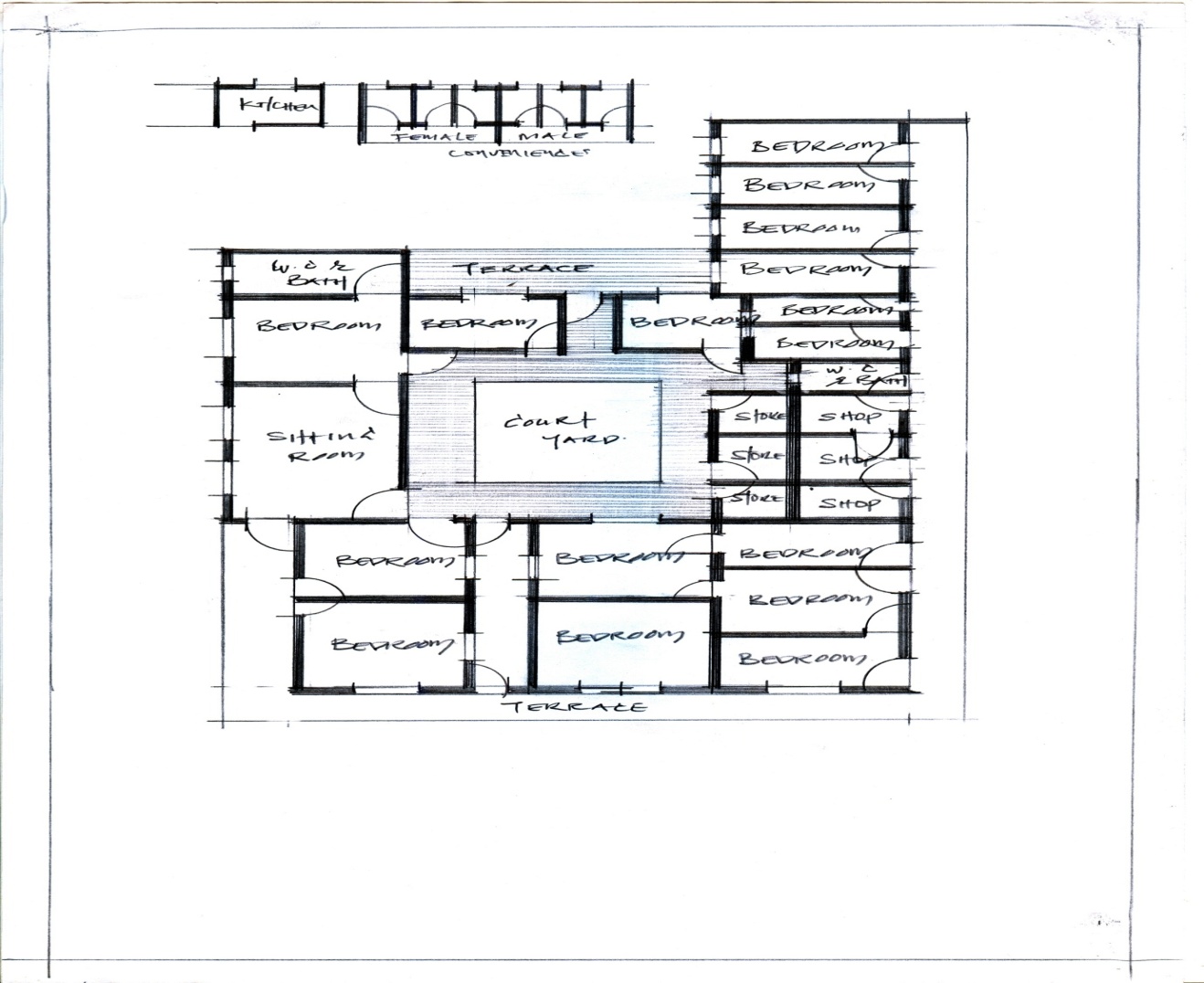

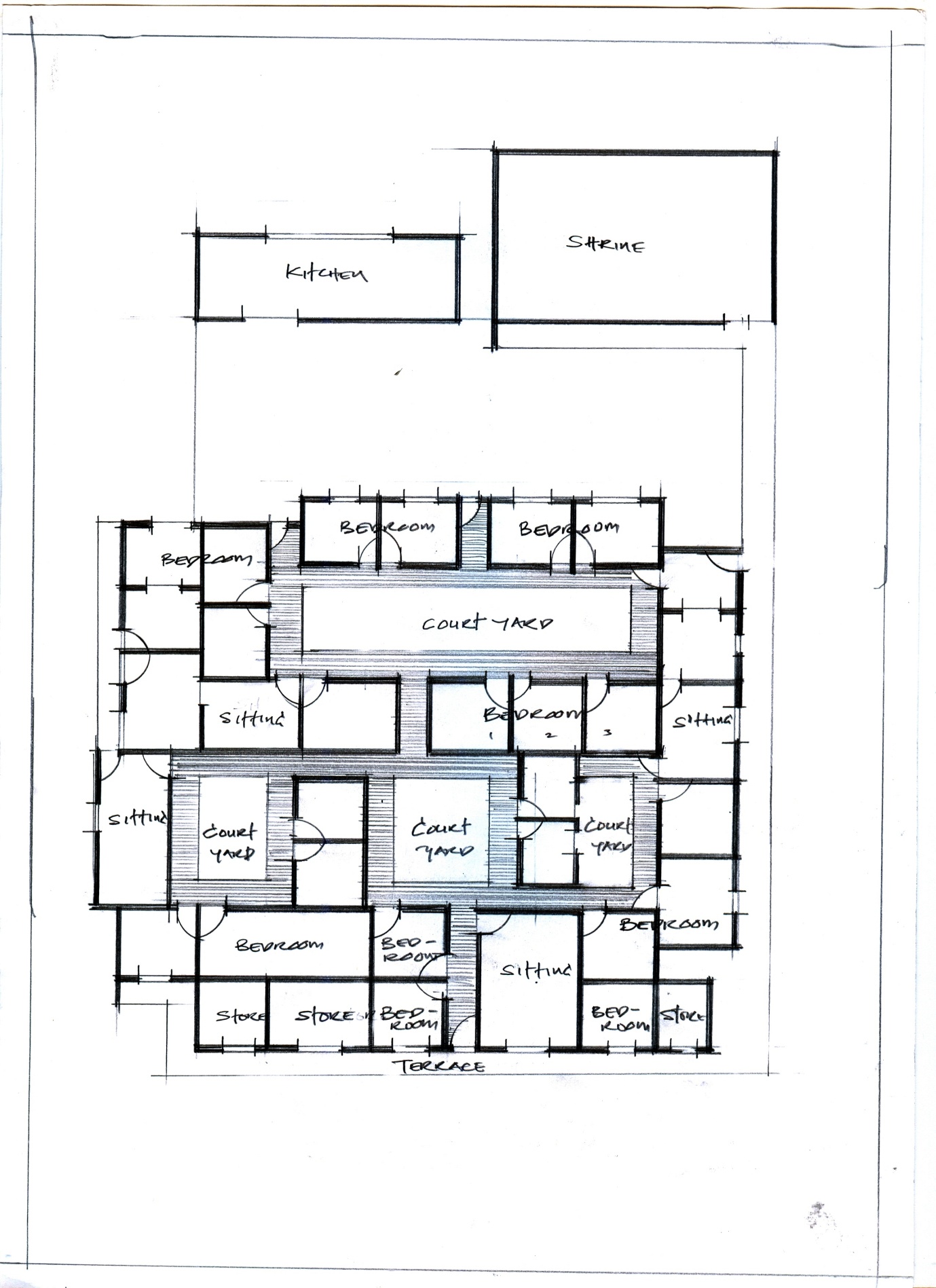

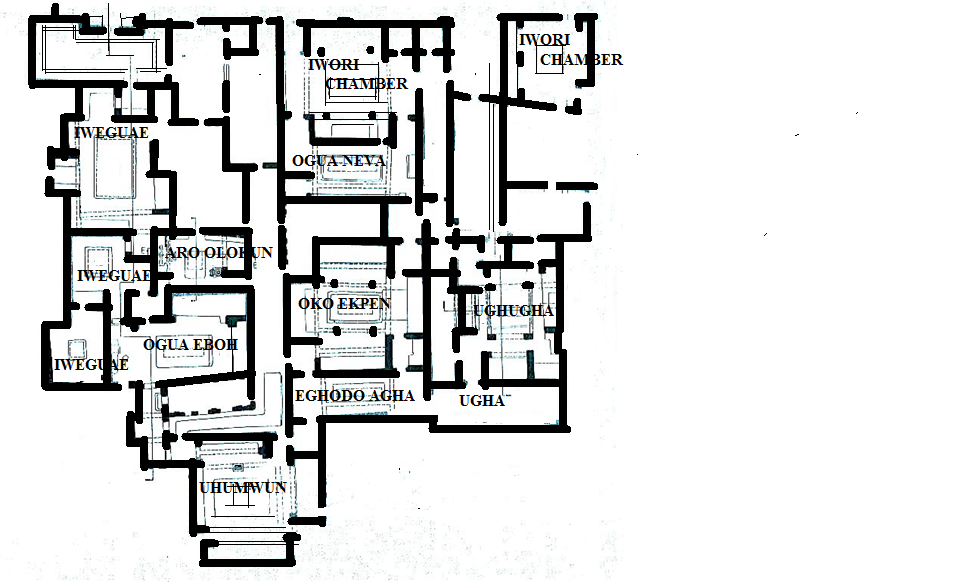

8.4. Owa’Eghaevbos (House/Palace of Chiefs)

- The houses of Benin chiefs are planned such that rooms are arranged around series of internal courtyards as shown in fig 6, leading one into the other like the Classical Roman house with its sequence of atria (Ekhaese, 2011). The roof over the courtyards admit light and air, while immediately below it, is a sunken impluvium floor with an outlet to drain storm water. The internal courtyard has a typical Mediterranean feature, with or without a peril-style of columns, depending on their size, but has couches and shrines constructed entirely of mud with surfaces polished to high glaze of remarkable quality of endurance so that even the oldest examples appear to have been recently built (Ekhaese, 2011). The sequence of courtyards ends in the chief’s apartments, while on each side are arranged the wives' and children’s harem. Externally the mud walls are finished in horizontal ribs pattern, a fashion of building that has continued. The roof which was originally of thatch has been replaced with corrugated iron, although the old method of construction continued, where heavy timbers sometimes ornamented with carving are carefully framed together around the roof opening. Doors, their jambs and wooden posts supporting the peril-style around larger courtyards are ornamented in the same way. Behind the rather average exterior is the main sequence of courtyards and apartments, surrounded on each side by rooms of lesser importance for womenfolk and boys, while the odd corners are taken up by numerous small rooms without windows which are used for storage. In Owa’eghaevbos the atria are very large; the first contains the Aruerha, the Paternal/Ancestral Altar as shown in fig 7.

| Figure 6. Floor Plan of the House of the Nobles and Wealthy In Benin City |

| Figure 7. Outer courtyard for shrines and 1dols (Ikun n’arhuera) |

| Figure 8. Floor Plan of the House/Palace of Chiefs in Benin City |

- On it stands a row of brass-plated wooden heads, shown wearing coral-bead collars, in front of a line of clatter sticks (Arthur, 1953).

8.5. Owa’ebo (House of Diviners)

- The residential house of divines like every Oto eghodo house has similar design and pattern with the house of nobles / chief's house. The owa'ebo is in the social class of the nobles with similar designs but different facades ornamentation. For instance the façade of divine's house is scary, unique and with specific ornamentation like: crocodile, bird, fish and sometimes mammy-spirits on the walls, doors and windows. Another difference is the back section where there is large shrine hall used for spiritual consultations.

8.6. Owa’hen (House/Palace of Chief Priest)

- The chief priest is a powerful and highly placed personality in the socio-political and socio-cultural hierarchy of Benin-kingdom. The houses though similar to hereditary chief’s palace in plan, design and pattern, yet the ornamentations on wall, fence, doors, windows, pillars and cornices are different. The chief priest compound is usually large than the hereditary chiefs’ compound and position of chief priest is hereditary. They are the custodian of culture, tradition, custom and believe of the people, this making them the mouth-piece of the gods of the land. The chief priest compound has between 4-15 courtyards and atria. Like the compound of the divine house, there is a large hall at the back section where the worship artefacts are kept. The walls of the house of chief priest have horizontal flutings and a height of seven layers.

| Figure 9. Floor Plan of the House of Diviners in Benin City |

| Figure 10. Floor Plan of the House/Palace of Chief Priests in Benin City |

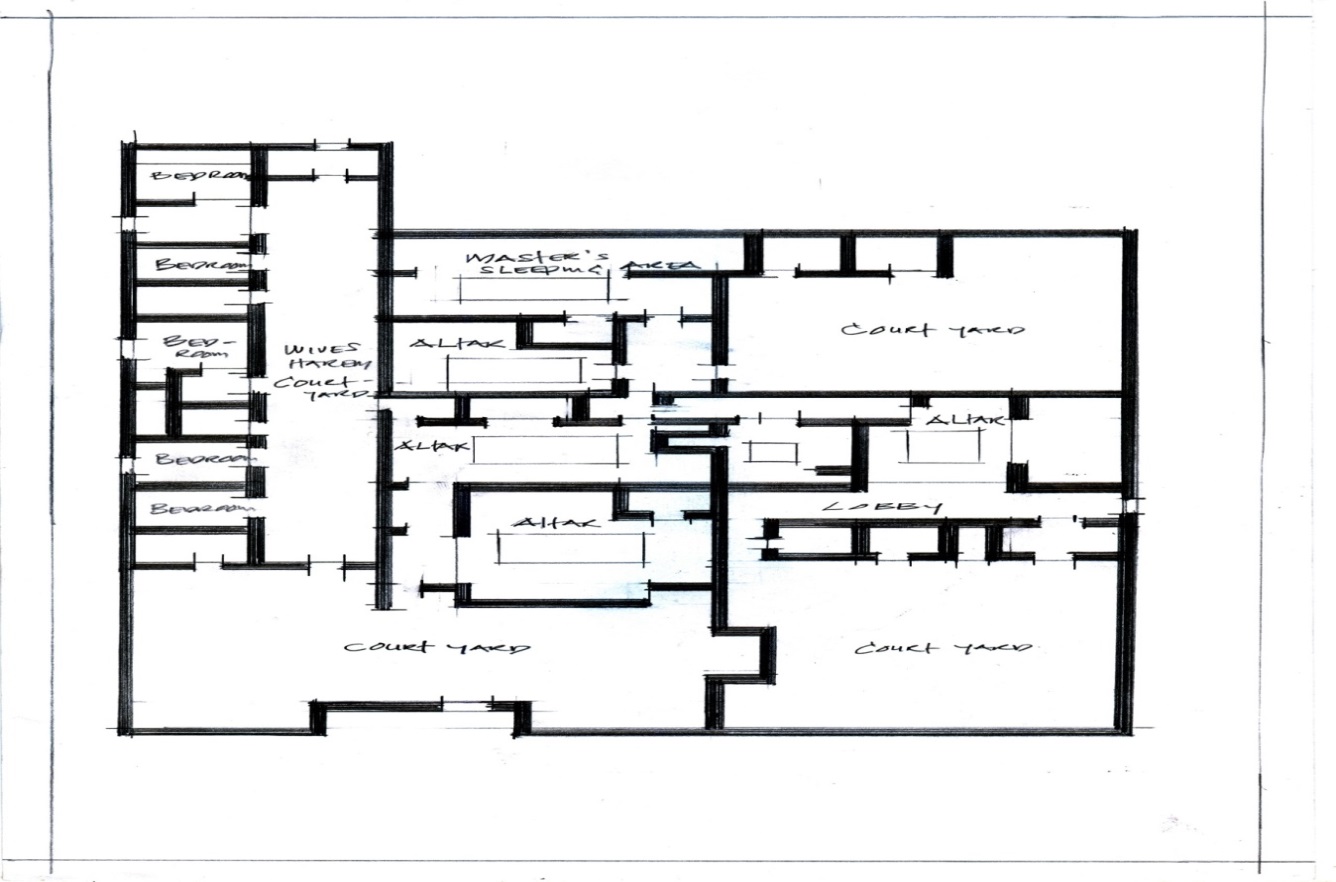

8.7. Eguei’ Enigies (Palace of Enigies)

- The houses/palace of Enogie in Benin kingdom is next to Oba’s palace because Enogie is the equivalent of a duke. As siblings of the Oba, Enogies are princes and deserve the same privileges. Therefore palace is planned such that rooms are arranged around a series of internal courtyards (Fig 11), leading one into the other with its sequence of atria.

| Figure 11. Series internal courtyard |

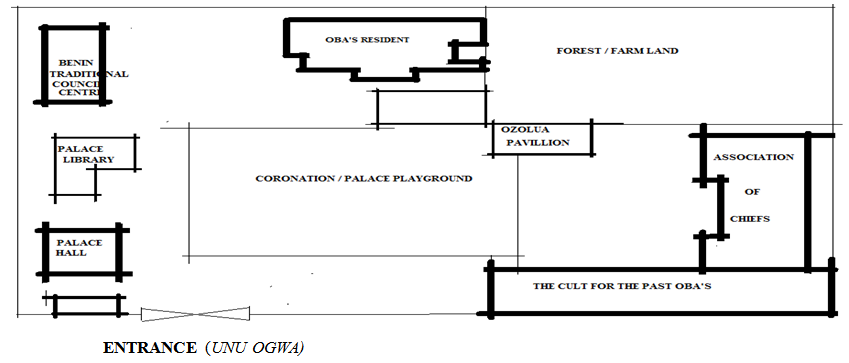

8.8. Eguei’ Oba (Palace of Oba)

- The palace of the Oba of Benin, Nigeria is very extensive. It is equally as large as a European town, with many courts surrounded by galleried buildings, their pillars encased in bronze plaques. Roofs are shingled with several high towers pinnacle with bronze birds. Everything traditionally takes its root from the Oba’s palace at the city core, from where all broad roads and streets radiate. The Oba palace has a large complex of homes in coursed mud, with hipped roofs of shingles or palm leaves utilizes indigenous traditions Architecture (Ekhaese, 2011).

| Figure 12. Floor Plan of the Palace of the Enigies in Benin City |

| Figure 13. Plan Show the Sketch of Oba’s Palace Layout |

| Figure 14. Floor Plan of the Palace of the Oba of Benin City (built up area) |

| Figure 15. Floor Plan of the Shrines of the Deities in Benin City |

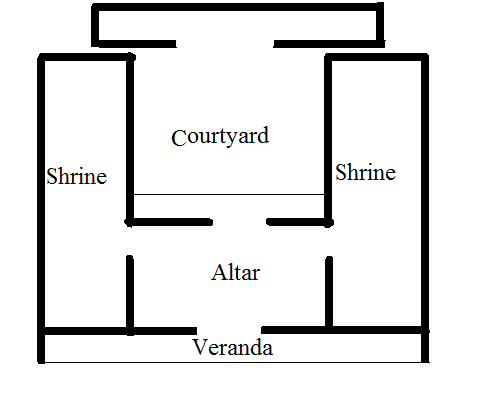

8.9. Ogua (Shrines of Deities)

- The Ogua is the shrine design for different deities in Benin that follows the Ikun concept design system. About sixteen special shrines dot the present day Benin- Metropolis that are still worshiped and revered till today. This showed the importance of Ogua to Edos. The shrine design is typical of Edos traditional courtyard design and it is the smallest courtyard house in Benin. Like the traditional courtyard house, the front section has a long veranda in front leading to the Ugha (i.e. altar hall), the hall opens to a large courtyard which accommodates large crowd during festivals and celebrations. The back section has convenience and hall used as storage for worship artefacts.

9. Concluding Remarks

- The Benin Oto eghodo house which is from Ikun concept of design has been discussed and described from owners’ perspective to have a rectangular pattern that can be easily divided into sections. It was develop to have different sections to accommodate large family (i.e. communal living). It was design to put the wives at the back section while house owner is located towards the front to protect the family. The Edos adopt the traditional form of worship (idol worship) hence there was need to accommodate altar in the house. The style and pattern of Edo courtyard house was intended to protect occupants from adverse climate and provide security. The structure of Benin social system determines the order for building houses. Consequently, Powerful people like dukes, chiefs and nobles build compounds, and lower social class persons stay in these houses temporarily, until they can build their own houses around these powerful men. And that is why cluster / pockets of small communities were named after the leaders, who formed these communities, e.g. Idumwu-Oliha, Ihimwenhin, Ugbeku Quarter, Isiwvero, Ikpema, Uzebu, Ekae, etc. In other words these are independent settlement built around the leaders of the communities. The Architecture of buildings in Benin relied on its functions that had both social and spiritual dimensions. The houses were laid-out to achieve courtyards that offered opportunities for open air living (Izomoh, 1994). The courtyards had multiple functions; either for domestic activities or as impluvium and are surrounded by verandas and small and dark bedrooms which only served as sleeping place at night. The characteristics of “Ikun concept of design”, (Edo “Oto eghedo” house) were discussed with reference to the layout pattern of Benin-city, spaces organization and activities space. Therefore, the architectural style, design and pattern is the same for all class of persons but the ornamentation and building size & height varies according to position in hierarchy. The traditional courtyard house were categorized based on the social, cultural and political status of the owners e.g. slave’s house (owa evies), Commoners’ houses (owa ogue), Nobles’ houses (Igie owa), Chiefs’ houses (Igi owa), Priests’ houses (Owa ebo), Dukes house (Eguai Enogie), Oba’s palace (Eguai) and shrine (Ogua). The difference in all the categories of houses is not the design but the sizes of compound. For instance, Ogieamien’s palace has 13 courtyards/atria while that of the Oba is 201 courtyards. It is clear that government, private partners and all actors in housing provision have working knowledge of the variable to consider in process of providing houses for all.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This paper has benefitted immensely from the assistance of director, Institutes of Benin Studies (IBS). The authors acknowledge the important contribution of Dr. Ekhaguosa Aisien, Prof. Bayo Amole and Prof. E.A. Adeyemi. The authors are solely responsible for any errors and omissions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML