-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2014; 4(1): 10-19

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20140401.02

Recomposition of Architecture in the Historical City. Case Study of Battaglia Terme, Italy

Enrico Pietrogrande, Alessandro Dalla Caneva

Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, University of Padua, Padua, 35131, Italy

Correspondence to: Enrico Pietrogrande, Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, University of Padua, Padua, 35131, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The work we propose concerns the theme of the recomposition of public spaces in the ancient town. The working method is based on the belief that, in the study of urban morphology, is basic to analyse the history of the city. The history becomes an indispensable tool to know the deep reasons of the urban structure which is the memory and the image of the community. The methodology contemplates the urban form as a result of its spatial structure. The life of the urban form is investigated in its physical specificity, the only one able of giving reason of its special nature over every social, economic and political aspect, certainly important but not sufficient. Our teaching at the University of Padova (Italy) is based on fundamental 1960s studies about typological analysis. The spatial aspects and formal image of the transformations in the city are studied as a premise for the design of the new architecture. The old town centre of Battaglia Terme, not far from Padova, is one of the subjects investigated by our students, thought as an opportunity to reconfigure the lost unity of a very symbolic and representative place.

Keywords: Urban analysis, Memory, Identity of the community

Cite this paper: Enrico Pietrogrande, Alessandro Dalla Caneva, Recomposition of Architecture in the Historical City. Case Study of Battaglia Terme, Italy, Architecture Research, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 10-19. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20140401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

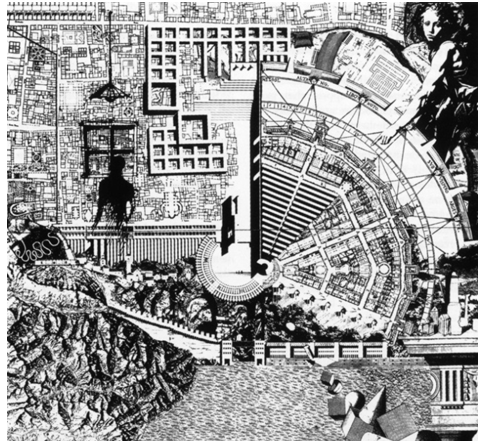

- The teaching experience presented in this article is based on the principle according to which studying the history of the city is an indispensable tool in discovering the underlying reasons for the development of the urban structure, which forms an indelible reminder made in the thought of the community. The protection of the urban landscape and its recomposition have to occur according to a coherent process based on a very close relationship between architecture and the city. The assumption is in line with the main contribution of the most advanced community of scholars in Italy on this subject during the second half of the twentieth century, the so-called School of Venice. According to lecturers who taught at the University Institute of Architecture in Venice, the relationship between a city and architecture, referring to the city’s scale in the study of architecture, is the fundamental fact that is at the origin of an effective theory on the project in the years following the war, which defines a synthesis between analysis and design, architecture and urban planning. Between the acquisition of information and work on artefacts.Explanation of planning outcomes in particular by Giuseppe Samonà, Egle Renata Trincanato, Saverio Muratori, and Aldo Rossi – to mention but a few of the most important members of staff at the University of Venice Institute of Architecture – in searching with the students to find ways of planning the future in the pre-existing urban fabric by using the concreteness of history as an instrument in combining individual architecture projects to give the public space shape and form [1]. Through the years the Venetian School has deepened research into the precise relationships between urban structure and architectural organism, theorizing a complete continuum between analysis of the urban environment and analysis of its buildings. Since the 1960s, studies in architectural typology and urban morphology have enjoyed a certain fortune in Italian design theory in regard to the construction of a rational architectural theory aimed at design practicality. This approach to architectural design is still considered by many to be of great relevance today, both from a theoretical perspective and in terms of methodology and teaching. The value of architectural typology derives from its study of historical forms, i.e. the reference to specific facts that can be compared to identify the basic motivations and essential aspects of real data.Aldo Rossi has the particular merit of having suggested a logical-aesthetic method capable of taking real situations into account in all their complexity, including accidents and random elements, without preconceived interpretive notions. In this sense, Aldo Rossi’s approach brought about a true revolution in the perspective of his time, proposing an architecture starting from real people as opposed to the modernist claim to create the present through preconceived interpretive schemes. Rossi therefore suggested a sense of proportion and renewal through the past (figures 1 and 2).

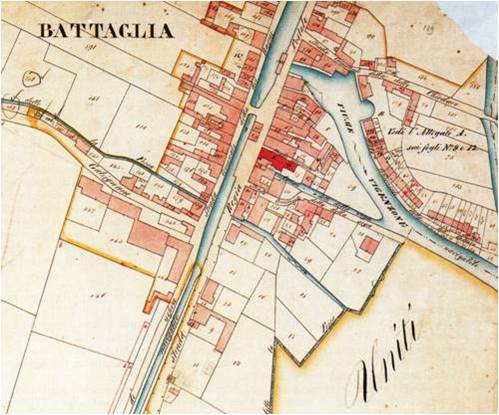

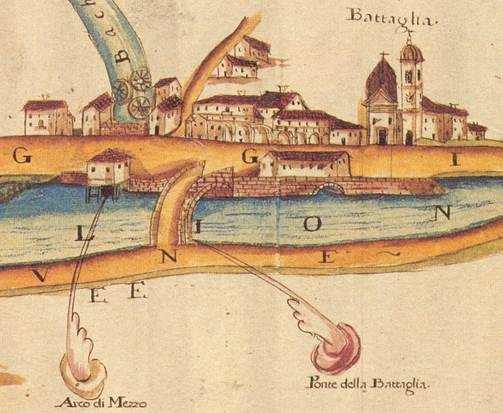

| Figure 3. The old centre of Battaglia Terme richly described in a detailed map of the year 1740, with the Arco di Mezzo and the water that underpass the road (on the left) |

2. Context

- Battaglia Terme is situated on the slopes of the Euganean Hills. It became known as an important commercial crossroads for river traffic following the construction of the first artificial canal in Europe, built between 1189 and 1201. The canal runs right through the town, where the waters from Padua meet the ones from Monselice and Longare, near Vicenza (figures 5 and 6). After negotiating the hydraulic regulation system at the Arco di Mezzo in the centre of Battaglia Terme (figure 7), the water then falls for about seven metres into the bed of the Vigenzone Canal and so makes its way to the sea (figure 8). The urban development of this area therefore depends heavily on the use of waterways and river commerce. This is one reason for the absence of a circle of walls around Battaglia Terme: a characteristic of other neighbouring towns such as Este, Monselice, and Montagnana.

2.1. General information about Battaglia Terme

- This important position on navigable waterways was therefore fundamental to the establishment of the town and its subsequent growth. From 1208 onwards, Battaglia Terme developed along the banks of the canal, initially as a centre of milling activity. It was designed to be an area wholly given over to the milling industry and to the exploitation of hydraulic power. The absence of defensive systems, such as walls and a castle, the continuing existence of marshland in the area at the end of the sixteenth century, and the constant interference by the Municipality of Padua, all point to a territorial entity heavily controlled from outside and developed as a sort of outlying industrial centre. The village became a supply base and a crossroads for the transport of goods (figure 9), especially of trachite stone. This was taken from the quarries in the Euganean Hills to both Padua and Venice, where it was used for paving open spaces and for various public works.

| Figure 9. Old view of the centre of Battaglia Terme, showing a burcio, a typical river craft, moving through the water (photo by Riccardo Cappellozza) |

2.2. Morphological and Typological Elements

- Battaglia Terme is more similar to a lagoon town than to other centres in the Paduan area. In the old town centre, the houses are all attached, and wind along the banks creating streets much like those in Venice or Chioggia. The two sides of the straight hanging canal are reserved for the noble residences, and behind the east bank, nestled in the Vigenzone Canal, is the old working-class district, once mainly inhabited by workers and boatmen. Here, the buildings are arranged in such a way as to create, within a labyrinth of alleyways, groups of dwellings clustered around shared courtyards. Access to the main street is by means of open passageways through the first row of houses, echoing in this system of “sottoporticos” the structure of Venetian squares. This urban layout, typically water-centred, took shape due to the presence of important navigable channels, which form a sort of water crossroads right here in Battaglia Terme. So, although surrounded by agricultural land, the town does not have the character of a farming centre.

3. Critical Aspects

- As a result of various erroneous planning decisions, the canal connecting Padova to Monselice, with national road no. 16 running alongside it, has gradually become more a divisive factor for the town’s community rather than an opportunity for collective growth as in the past. Since the 1930s, Battaglia Terme has developed exclusively on the western side of the canal, leaving the eastern side where the town centre grew up over many centuries, to fall progressively into decay. Nowadays, what remains of the old town is in a very dilapidated state (figure 10), and on the way to being abandoned by its inhabitants. While to the west the modern town is extending outwards beyond the railway station, in the area on the opposite side the process of deterioration has greatly increased in recent decades.

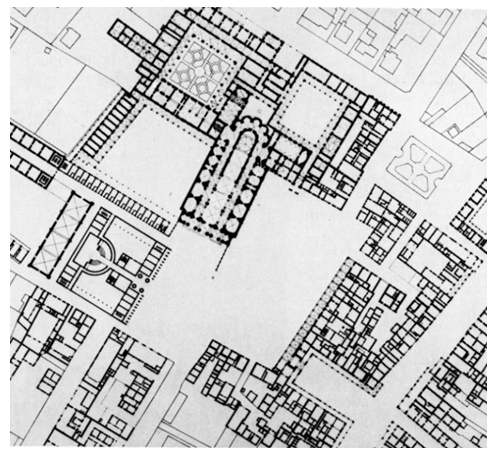

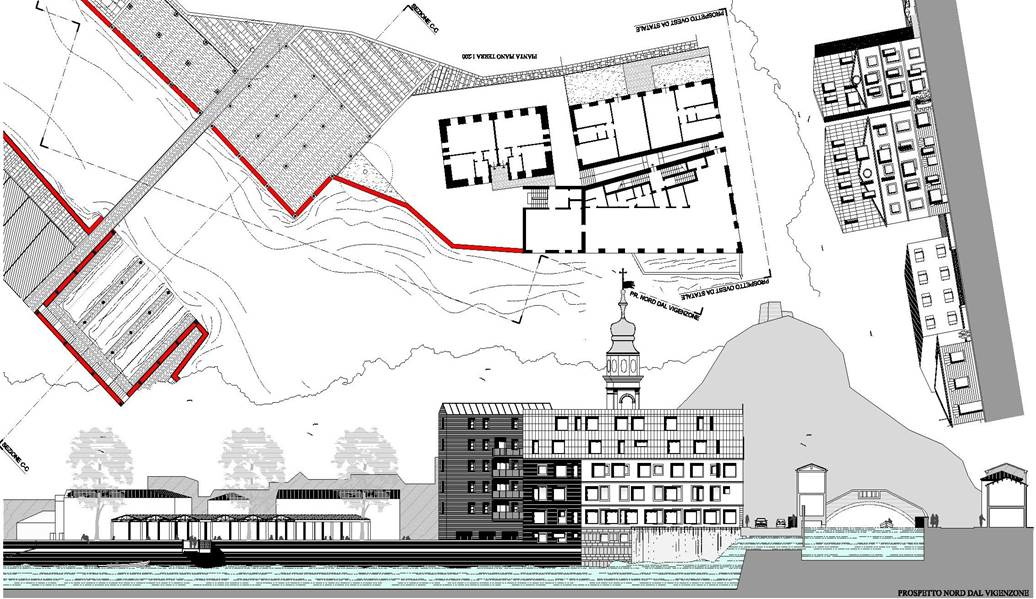

| Figure 10. Old centre of Battaglia Terme, current state. Planivolumetric plan. From the work of the students Marco Fortuna and Alessio Lorenzetto |

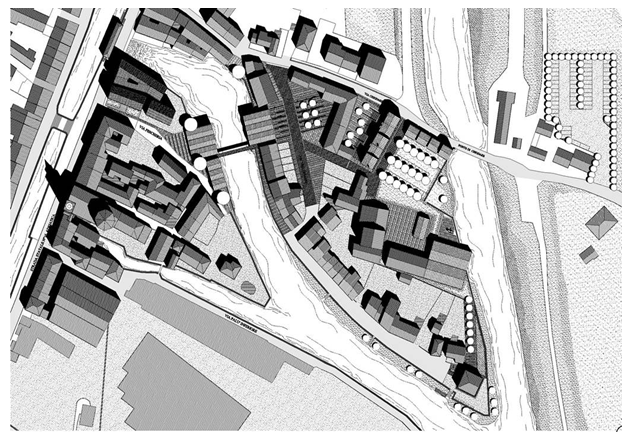

4. Project Hypothesis as Didactic Experience

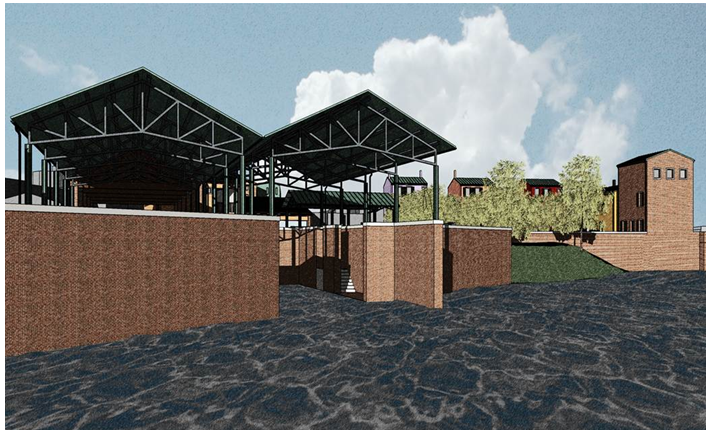

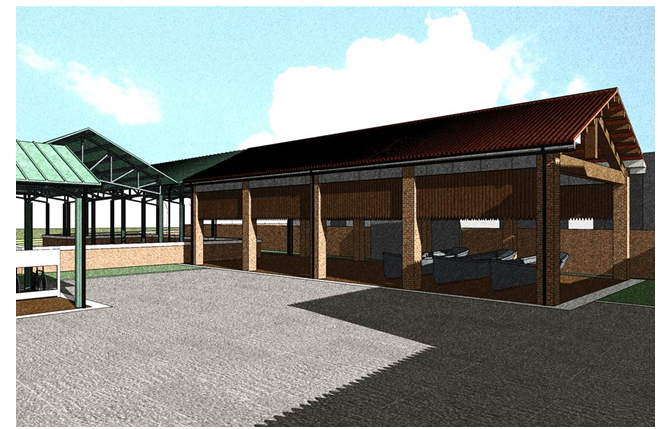

- Research into this particular issue was one of the main subjects proposed to students as part of the master’s degree in Architectural Engineering at the University of Padua. This was within the context of finding ways to upgrade our neglected architectural heritage and natural resources, and to promote and encourage ecological tourism. Two undergraduates, Marco Fortuna and Alessio Lorenzetto, chose a study of Battaglia Terme as the subject for their final thesis. The aim was to draw up new proposals for revitalising the historic centre, now disused waterway junction in the lower Padova region, and to develop ways to convert it from an abandoned industrial hub into a popular tourist destination. Fortuna and Lorenzetto were asked to formulate planning hypotheses starting by considering architectural analysis as part of the project.The general guidelines put forward can be summarised as follows: 1. making the area into a traffic-free zone, with access restricted to pedestrians, cyclists and residents’ cars; 2. partial enlargement and reclamation of the Cobelli shipyard, and demolition of some of the tower blocks erected around the 1970s (and which are particularly incongruous) in favour of a series of new buildings aimed at tourism; 3. upgrading of the waterways, and their integration into new harbour facilities, providing the opportunity to travel as far as Venice, via Bovolenta and Chioggia, or Padua and Vicenza, either by your own boat or by that of the municipality; 4. development and improvement of the existing Museum of River Navigation; 5. establishment of new routes for cycle-tourism and upgrading of the existing ones, in response to the growing demand for sports tourism in the context of the Euganean Hills and in the Veneto region in general. Cycle-tourism is becoming increasingly popular here, practised both by Italian tourists and those from northern Europe, who are attracted by the presence of the thermal springs too. The proposal put forward by Alessio Lorenzetto and Marco Fortuna (figure 11) is in keeping with the general approach, directed at enhancing the urban landscape while preserving its existing historical and environmental features, and so ensuring that the necessary improvements demanded by modernisation are in tune with the traditional context. In fact, the urban design is here understood as the result of a dialectic between the values of tradition and modernity.

5. Discussion

- The research and results produced by the Venetian school in typological and morphological studies were further advanced by a generation of young architects who believed in the possibility of rethinking architecture based on the premises of rational thought. This position, in the opinion of Antonio Monesteroli, “understands architecture as knowledge of reality, built on the underlying reasons that produced it, with the intention of making these discernible in the building. This position is linked to classic architecture, with its declared objectives, displayed construction methods and works that conform to these objectives and methods. There are examples of this approach that merit further research. We can affirm that this position has produced a theory of rational architecture.” [5]. In this sense, architecture becomes a representation of a manifest thought, an opportunity for learning: “Architecture is knowledge and projects are its main tool of verification and research aimed at understanding the city and its territory” [6].A generation of architects and academics have been trained on the basis of this rational thought, and despite belonging to different schools, with their own autonomy, they are able to recognise themselves in a cultural reference environment in which the sharing of themes and issues, and adherence to common principles and foundations, has in effect led to the development of a school. Following the footsteps of Aldo Rossi and the great masters of rationalist culture, they understand the role of architecture in collective rather than individual terms. From this perspective, rational culture offers the only possibility to recover the most essential and constitutive aspects of reality, where the particular and the individual are recognised in the collective. “The artist’s life and the history of society” Gianni Fabbri wrote “share this common point given by the monument, by the architecture produced by individual inventiveness, which is recognised as a part of collective history. This is where subjectivity dissolves into a collective dimension and acquires its objective character” [7]. Therefore, as part of a logical process that allows compliance with the intrinsic rules of the profession, personal experience is never denied but always channelled within a broader collective experience that never departs from the civil nature of architecture and the architect’s responsibility. The composition is still a response to the need to rediscover the sense of a productive tension between individual expressive sensibilities and commitment to the community, between being an artist and the usefulness of the artist.Architecture is therefore understood as social art. The composition is the work of an individual but designed for the entire community or city. The city is always the common object of study for the members of the school and architecture is the element that defines the city itself. In this sense, a project is understood as an “analogous city”, composed of fragments, rediscovered architecture, known forms assembled in a new way, able to evoke meanings, create infinite relationships with the city and, in fact, propose an alternative reality through the use of imagination. Thus the invented design consists of forms that are already known, and is therefore the result of a dialectical relationship with history, which is studied to rediscover new aspects and features. As Gianugo Polesello says, “architecture is like a large archive that includes what is already given and available, and in what is available there is also architecture to be realised, invented and proposed” [8]. However, these known forms that belong to tradition are simple, communal forms that refer to a civil dimension of architecture: they represent the shared values in which a community recognises its presence in the world.“I therefore support a civil dimension of architecture”, Malacarne wrote, “in which urban and architectural forms are the reflection of a collective experience that can minimise the individual aspect of the works by subjecting the form to an idea intended to be intelligible and even shared. I agree with those ideas of cities referred to known places that are transcribed, reinvented and found in the project, recalling with Cesare Pavese the true wonder is in the memory and not in the new” [6]. The students of Aldo Rossi refer to this formal tradition because, for them, “the problem was not so much how the world functions, as how to represent its values” [9]. This was a new point of view, which, by placing people and their lives at the centre, allowed light to be shed on a regulated system: “It is a logical process that allows people to follow the rules, the traditions of the profession and perhaps even a certain naturalism, but in which the uniqueness of personal experience, through the choice of objects and the proposal of novel solutions, is what makes the system extraordinarily alive” [10]. This research, in the impermanence and lack of values of the time in which we live, has now become more relevant than ever.

6. Conclusions

- The study of the relationship between architecture and culture of the city lies at the heart of the above displayed planning hypotheses. In-depth study of the history of Battaglia Terme is an instrument that clarifies the main aspects and opportunities.In particular, the research into the transformations of the spaces and shapes developing through time represented an indispensable premise for checking the planning proposal that aimed at reconstituting a coherent urban fabric in which residential and touristic uses play a role in connecting the distinct monumental phenomena present.The investigation of the history of the city formed the basis of the project solution illustrated above, in harmony with the belief that in teaching it is essential to promote a synthesis between knowing and doing. The study of what is already present in the area and the broader historical-building framework is an essential tool in the promotion of a new cultural layout based on the needs of the area. The future image of Battaglia Terme also depends on the choices that will be made about the old city. The search for a formal reordering is motivated by the conviction that architecture is a fundamental means for promoting a new cultural and social asset in the areas investigated, where the new architecture draws inspiration from the needs of the territory. The on-going teaching experience at the University of Padova has also proved to be effective in making the relationship between lecturers and students a cohesive one.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank the Planning Department of the Municipality of Battaglia Terme for their help to the students in this learning experience. Thanks are due also to the interviewed inhabitants who have expressed useful suggestions for the project.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML