-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2013; 3(4): 51-61

doi:10.5923/j.arch.20130304.01

Encouraging Visitors: A New Set of Guidelines for Designing Prison Visitors’ Centres

Emmanuel Conias, Mirko Guaralda

Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, 4000, Australia

Correspondence to: Mirko Guaralda, Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, 4000, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Visitors to prison are generally innocent of committing crime, but their interaction with inmates has been studied as a possible incentive to reduce recidivism. The way visitors’ centres are currently designed takes in consideration mainly security principles and the needs of guards or prison management. The human experience of the relatives or friends aiming to provide emotional support to inmates is usually not considered; facilities have been designed with an approach that often discourages people from visiting. This paper discusses possible principles to design prison visitors’ centres taking in consideration practical needs, but also human factors. A comparative case study analysis of different secure typologies, like libraries, airports or children hospitals, provides suggestions about how to approach the design of prison in order to ensure the visitor is not punished for the crimes of those they are visiting.

Keywords: Design, Secure Environment, Case Studies

Cite this paper: Emmanuel Conias, Mirko Guaralda, Encouraging Visitors: A New Set of Guidelines for Designing Prison Visitors’ Centres, Architecture Research, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 51-61. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20130304.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is accepted amongst prison researchers that visitors have an undeniably positive influence on prisoners, levels of recidivism or repeat offence[1-4]. This is because visitors provide the incarcerated with an outlet from the secluded prison system and re-link them with their lives outside prison[5]. Researchers and prison operators alike have generally accepted the value of visitors[4], more radical positions suggests all institutions should encourage visits from family and friends[1]. Sufficient research exists about the benefit of visitors for prisoners, the same cannot be said for the effects of prisons on visitors; existing research warrants concern as it demonstrates that impacts on visitors are not always favourable[5, 6].Few sources deal directly with this matter; Comfort[7] for example claim that visitors ‘do time’ with their loved ones undergoing a ‘secondary prisonization’. This implies that the sentence of the offender is also passed down to their family that has to deal not only with practical issues, but also emotional ones connected to the access to secure facilities.Whilst there is little that architectural design can do to assist in the many issues associated with incarceration, intimidation and the physical atmosphere of a prison’s visitor centre can be addressed.Pilot projects about more visitor friendly facilities have been developed by PACT in the United Kingdom, for example HM Prison Holloway[8], but a general theoretical discussion about the design of this places has not been fully addressed by literature.This study begins by reviewing the current state of visitor centres and the factors that are presently incorporated in them. It focuses primarily on contact visits, visit in which visitors can make physical contact with the incarcerated whereas a non-contact visit typically takes place with a glass wall between the two groups[9]. The specific type of prison (i.e. maximum or minimum security) is not relevant for the investigation that focuses exclusively on the human experience of visitors and the specific environments to interface inmates with family and friends. The type of visit and how this is translated in architectural terms is discussed in regard to their impacts on people; therefore the study aims to provide an alternative approach to the design of visitors’ centres.Secure environments are not unique to detention facilities; other function and activities deal with the problem to protect, isolate and, at the same time, provide an interface between internal and external users or guest. This research evaluates how secure environment and human experience are negotiated in three different typologies in order to draft possible principles applicable also to prison design. Three case studies, an airport, a library, and a children’s hospital, have been selected as they provide a sufficient variety of building types, design approaches and scale. Security is the paramount concern in the design of prisons[10]; this research discusses how level of security have been maintained in the chosen typologies but, at the same time, a user friendly environment has been promoted. The airport has been selected as a case of how screenings of users and controlled access have been mediated through systematic use of technology and streamlined processes. Libraries and hospitals are traditionally typologies that have been designed with an institutional approach, often with intimidating or sterile architecture in order to convey an idea of respect or efficiency. More recently these typologies have been reinvented to provide a more user centred and relaxing environment[11-13].These facilities are assessed on how they are designed to both remain secure and accommodate visitors. In essence, several of their security protocols are not dissimilar from prisons in their initial function, even if they differ in apparent intensity and human experience. The case studies are analysed according to three types of security paradigms: architectural, security consultants and operational.This paper, through induction, investigates which design principles have been applied in the selected typologies and how these could be translated to prison visitors’ centres. Whilst jails are inherently complex typologies, this study focuses exclusively on the design of the interface between inmates and their family or friends. It is recognised that other factors influence recidivism, but this paper investigates only the role of visitors and their needs.

2. Literature Review: Impacts of Prisons on Visitors

- To understand the complexity of issues associated with prison visitors’ centres, one must understand the various groups involved. There are three groups of people who have needs: the prisoners, the visitors and the guards.

2.1. Prisoners

- For the prisoner, the visitor means the outside world. This has been accepted for many years. Governor Darling, for example, when establishing Norfolk Island prison in the 1800s, had women banned from visiting the island. According to Hirst[4], Darling’s logic was that ‘he did not want the discipline of the prison disturbed by the comforting regularities of family life.’ Visits provide the prisoners with something to look forward to that breaks the monotony of prison life and allows them to invest in meaningful relationships whilst incarcerated in a place where these relationships are not in abundance[1, 7]. They also provide an easier reintegration into society, which may be one of the factors in lowering recidivism[1]. To summarise, visitors make prisoners feel as if they were still part of the world. It should not be assumed, however, that because a prisoner has visitors they will instantly stop committing crimes but rather that their chances of successful reintegration will increase. Dixey and Woodall[2] discovered that several prisoners were simply in the habit of committing crimes even though they had supportive families and homes.

2.2. Visitors

- Whilst visitors are still part of this outside world, as stated earlier, they can undergo a secondary prisonization. When defining visitors for this report, it can be assumed that it is in regards to partners, family members and children. Whilst others also visit, according to Dixey and Woodall[2], these groups are the most heavily impacted. Because many of family members wish to remain in constant contact with the incarcerated individual, their outside activities can also be hindered[5]. By removing a partner from a typical daily equation, the lives of the ‘free’ members can be severely impacted. Most prisons are developed in fairly isolated contexts often requiring a great length of travel. This, coupled with inflexible visiting hours, can generate difficulties in accessing facilities, long waiting times and can cause the loss of money[6]. Partners are also often forced to provide financial support for the incarcerated, leading to further complications[5]. The above demonstrates only a few of the issues involved that can cause problems for visitors.As mentioned, children are also impacted, as Murray[3] observes that limited research to date suggests that ‘imprisonment can have devastating consequences for partners and offspring.’ He claims that 92% of prisoners in the U.S. had fathers in prison and he raised concerns about the encouragement of crime in the next generation[3]. Aside from parental influence, in the setting of the visit, young children are distracted easily and families are often threatened with visit termination if they fail to control their kids. This, in turn, affects the parents’ ability to enjoy themselves. Irrespective of these points however, Murray[3] claims that children generally liked having contact with their parent regardless of the prison and adolescents felt that this contact was extremely important to them. Similarly, whilst most sources focus on the negatives of prison’s impact on families, Dixey and Woodall[2] discuss the sense of achievement that is often felt by maintaining and strengthening relationships through hardship for the sake of the partner in prison. This final point could describe the ultimate goal of the prison visit process and should be encouraged by design as much as possible.

2.3. Guards

- The final group of importance are the guards; those who are charged with maintaining the security of the facility. When discussing families in visits, it is easy to forget that one group are in fact offenders convicted of committing crimes and that visitors do not always have the best intentions regarding laws and protocols. Literature acknowledges visitors as being the primary pipeline for drugs into prisons[1]. The role of guards is to stop illicit traffics as best as possible and ensure that the law is upheld. Unfortunately, the security processes and the strictness with which they are implemented often create an uncomfortable situation for many visitors, which is where the issue of the visitors’ centre design begins. It is this precise dilemma of prioritising security over the encouragement of visitors that has made this research necessary.

3. Design Research and Results

3.1. Visitors’ Centre Analysis

- When observing the typical visitors’ centre, one may notice that the comfort or accommodation of the users is not a particularly urgent priority[8]. This is not to say the centres are not functional; there are sturdy and well structured. Security protocols are incorporated to minimize illegal activities and there are clear expectations of where one can and cannot go; fixed seating arrangements allow each group their own small space[10, 14]. These centres are indeed functional in term of safety and control. The real complication however relates to whether or not the strategy developed to create a secure environment also provides an accommodating and encouraging setting[3]. In order to discuss alternate methods of designing visitors’ centres, there must first be an analysis of their current issues. Whilst the intent is to meet everyone’s needs (prisoners, visitors and guards), the impression currently given is that functional processes are prioritised over the needs of the users.Security features and precautions are necessary throughout prisons and, if not more so, in visitors’ centres to assist in dealing with threats to the law[9]. There are numerous reasons for security features and precautions including the safety of visitors, prisoners and guards, keeping prisoners from escaping and deterring the smuggling of drugs. Whilst the desired security outcomes cannot be guaranteed, strict security measures and policies are implemented in an attempt to limit breaches[10]. These security measures appear to be broken up into various types and levels of intensity. The first of these is primarily architectural; solid, bolted furniture items leaving little leeway for flexibility, solid and unforgiving building construction and high, unsightly external walls housing strategically located buildings. These and other forms of design are used to deter escape, property damage, encourage safety and provide a sense of control[14]. The next level of security is technological; it comes in the form of closed circuit television equipment (hereafter CCTV), X-ray machines, metal detectors, restricted door access, and computer searches for background checks. These pieces of equipment can have a number of different emotional impacts on visitors, though they alone do not create a sense of intimidation for the majority of people. If similar instruments can be justified in airports as standard protocol, then it seems feasible that they would appear in prisons[14].The final level of security comes in the form of operational philosophies. These include the roles, attitudes and number of guards, restriction of possessions allowed into the visitors’ centre, sniffer dogs and full body or strip searches. Also included here is limiting visitors’ hours to a very specific time once a week[5, 9]. Essentially, these security measures aim to nullify potential threats, however, they also have undesirable impacts on visitors[6]. Our previously discussed visitor groups are often impacted in different ways. Partners of incarcerated prisoners do not always feel comfortable with the various searches required before entering and then the often-strict demeanour required when inside[5]. Uneasiness has been expressed in regard to the levels of acceptable intimacy, not necessarily physically, but also emotionally as guards watch them. Partners also tend to find that the restricted time of the visiting hours impacts their lives[5].Visitors with young children seem to encounter the most difficulty with the prisons’ system. Dixey and Woodall[2], in an interview with an offender, found that the guards often had impossible expectations in regards to the control of children. The prisoner stated that expecting his two year old child to remain silent for two hours and being threatened with the termination of the visit for failure to do so was unfair and unrealistic. Murray[3] reiterates these feelings when he states that ‘prisons are clearly not family-friendly places to access. Poor facilities and hostile attitudes of staff can put families off visiting, especially those with children.’ It has been established and accepted almost universally that visitors are beneficial to the wellbeing of prisoners and in lowering levels of recidivism and re-offence. If visitors assist in rehabilitation, then perhaps visitors’ centres should be seeking to encourage visitors rather than making them defensive and uneasy. This sentiment can be best seen in Codd’s[5] work when quoting Brookes, who proposes that if a visitors’ centre receives $40,000 of the prison budget, it should be doubled to $80,000. If a prisoner reoffends, it costs $111,300 to house them for a year. Brookes suggests that the monetary saving of encouraging reform through a better visitors’ centre is justified should only one prisoner reform per year as a result. Brookes’ proposition poses the interesting thought that by allocating extra money from the budget to better-designed visitors’ centres, not only can improve users’ comfort and experience, but levels of recidivism may decrease also.As stated secure environments are not unique to prisons; other typologies deal with similar issues, but adopting a different approach in term of users’ experience and overall environment.

3.2. The Airport

- The airport, as a building typology, involves a grand scale of building and a complex level of security risk[12]. Documents for airport security considerations such as Recommended Security Guidelines for Airport Planning, Design and Construction by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security[15] (hereafter USDHS) show just how in depth considerations need to be in order to maintain a secure airport.Many people are impacted by airport security because of the multi-directional functions of this environment. There are passengers travelling domestically and internationally, airport staff, airport security, people picking up and sending off passengers, store operators, and so on[16]. One of the most challenging issues faced by the planning team, according to the USDHS[15], is: ‘not only to make the best possible operational, economic and business use of space within the terminal, but in doing so, to provide the passenger and public an acceptable level of comfort for their experience.’Because the intention of this report is to focus on visitors’ centres, not all these groups will be discussed. However, it is important to know that there are multi-levels and people groups that impact airport security in much the same way they do in prisons[17]. As with the other case studies, the needs of three primary groups are discussed: passengers, visitors and security staff. The needs of the passengers are to reach their destinations via the planes housed at the airport. They need to feel safe and to be able to progress through checkpoints at a reasonable speed. Visitors or ‘meeters and greeters’ as described by the USDHS[15] need to spend time with those who are leaving in a comfortable, safe environment. Like the passengers, they also need to progress fairly quickly through checkpoints without unnecessary delays[12]. Security staff is required to ensure that the airport is safe from potential terrorist attacks and that all passengers are screened properly in order to minimise risk.Because of high profile terrorist attacks in recent years, nearly all parties involved in airports are treated not only as potential victims but also as potential threats. This also includes guards and airport staff. The USDHS[15] makes recommendations for limiting the screening entrances of staff in order to ensure the security risks they pose are limited. In respect to prisons, this philosophy can and should also be applied. Statistically, aside from visitors, corrupt guards have also been responsible for drug and contraband trafficking in prisons. In this respect, all groups can be suspects[16].Meeters and greeters, according to the USDHS[15], are those ‘who tend to populate the non-secure public side of the terminal building[and are] highly important security concerns.’ The USDHS’s last comment shows these visitors to be a sort of double-edged sword, demonstrating that whilst most are there to be protected, some are there with ill intentions and need to be protected against. A similar definition can and is applied to prison visitors and explains the intense security precautions taken upon entry.As has been established, airport security is particularly complex. Unfortunately, airport design is a task that Rafi Ron, president of the security consultancy firm New Age Security Solutions, believes is currently being run ‘by engineering departments working with external engineering firms with no security expertise.’ In his interview with Jones[18], he argues that in the complexities involved in airport design, the role of a security consultant is of great importance. The layout of the airport is separated into two sections: landside and airside. Landside could also be described as the public side; the side before passengers are required to screen both their luggage and themselves. According to the USDHS[15], ‘as long as there is a “public side” within the terminal, where congregations are expected, there are limited means by which a security system can prevent an attack.’ Because of this, it is recommended that architects develop a form of screening that can take place prior to entering the building, which in turn allows for a ‘sterile’ environment and increased safety within. This notion could be applied to the prison visitors’ centre. Typically, visitors’ wait in another building whilst the incarcerated are being moved to the visitors’ centre. Whilst screening typically takes place immediately prior to entering the visitors’ hall with the incarcerated individuals, the possibility of implementing screening upon entry to the initial waiting zone may sufficiently reduce the impact screenings could have. Most visitors arrive early for their visit, this ensures that they do not miss out as once the visit time begins, no-one is permitted in or out of the centre. If screenings began prior to admittance to the centre, visitors, especially parents with children, could have more time to recover from the screening’s impact whilst they are transported to a waiting lobby within the centre.Transition is an extremely important aspect of airport design. According to Rafi[18]:‘It often happens that a poorly designed secure environment is translated into passenger and tenant frustration and rage. The public respects, in most cases, the need for security and is willing to pay a logical price in inconvenience. What the public is not willing to accept is unprofessional and illogically enforced solutions.’This statement can be verified through various testimonies produced by Dixey and Woodall[2]. According to the USDHS[15], ‘one of the fundamental concepts for airport security is the establishment of a boundary between the public areas and the areas controlled for security purposes.’ As was the situation with libraries, the designers must cater for the various activities that take place between ‘public’ space and ‘secure’ space ‘whilst permitting efficient and secure methods for a transition between the two’[16].The general public are well aware of the security requirements of an airport and why they are in place[12]. Large scale pieces of equipment such as X-ray machines and metal detectors are of little impact because people are aware of their existence and their function. As with most secure facilities, these pieces of equipment are used in conjunction with security staff and it seems that two critical factors arise from this. The first issue is the ‘emphasis on efficient queue management, passenger education and divestiture in this area will greatly improve the efficiency of operations for all’[15, 16]. Whist the public know about the machines, guidance and efficiency through them will help to relieve frustration. This can be encouraged through architectural techniques such as use of colour or materials on floors that immediately guide people to where they should queue up and stop and what areas are not permitted for crossing[12, 16]. The second issue is that these security zones are always accompanied by security staff. The attitudes of security staff can have a severe impact upon people’s experiences. Combining effective, fluid transitions and cooperative staff can assist to create a more pleasant experience from what could otherwise become stressful and intimidating.

3.3. The Library

- The second case study to be discussed is the library. McComb[11] in his work on library security suggests that before one can design a secure facility, they must first establish for whom they are designing; what their design is seeking to accomplish. From here, one can determine the level of security required, the means to accomplish it and how it will impact the potential different users it[19]. When comparing the library with the prison, it may not seem that there are any similarities; however, if a closer look is taken, one can observe that they are both in fact secure facilities. A prison houses convicted offenders whereas a library houses books. In both situations, those being housed are not allowed to leave the premises without permission and both, quite relevantly to this research, respond well when people come to visit. Clearly a library and a prison are two complete different typologies, but the design solution to secure a public book collection can inform the development of a friendlier environment in visitors’ centres.McComb[11] efficiently summarises the intentions of a secure library. He states: ‘The goal of the security system should be to provide a safe and secure facility for library employees, library resources and equipment, and library patrons. At the same time, the security system must perform these functions as seamlessly as possible, without interfering with the library’s objective of easily and simply providing patron services.’There are three groups with different needs in regards to the security of the library: the librarians, the books and the visitors[19]. The librarians’ needs are to know that the books are protected and that they can supervise all areas from a distance. The visitors need to be able to access books as necessary without hindrance or delay. The books, unlike prisoners, are not active and require protection. The key areas of exploration in this case study are two-fold, focusing on accommodation of visitors and security of books[20].To re-emphasise McComb’s analysis, the key is to provide a system that will protect the books, visitors and staff but not interfere with the library’s ability to encourage people to come and visit the books. The WBDG[21] also reiterate McComb’s comment suggesting that a ‘truly functional building will require a thorough analysis of the parts of the design problem and the application of creative synthesis in a solution that integrates the parts in a coherent and optimal operating manner.’As with prisons, various zones of the library require various levels of security; the primary points of concern are the entry and exits. McComb[11] claims that when designing a new library, in order to reduce threat of theft, ‘the ideal arrangement is a single point of entry to the secure area of the facility.’ Anti-theft detection devices can be placed around these points in order to deter and detect visitors attempting to steal. Their intimidation levels are low; if a person were to go to a local supermarket they would see a similar piece of equipment. People are accustomed to seeing them, know their function and understand their implications and therefore accept them. However, as far as physical equipment is concerned this is the extent of what could be labelled an intimidating device as most other implemented methods are either architecture based, subtly implemented or operator-run security[20]. Whilst prison equipment is on a vastly higher level of intensity, X-ray scanners, large metal detectors and other pieces of equipment may be able to take a more subtle approach. Architecturally, the placement of the librarians’ desk plays a key role in passive surveillance[19]. These are typically located near the entries and exits and overlook rare collections. Similarly, they overlook areas with work desks where people use the books. The ability to survey the environment from the librarians’ desks not only allows peace of mind for the librarians, but also creates a sort of passive surveillance, which causes potential thieves or vandal to occasionally second guess themselves; those who are using books responsibly, on the other hand, have no reason to feel uncomfortable[19]. Libraries also demonstrate non-secure techniques that can make a visitors’ centre more comfortable. By utilising softer materials, natural light and colour as opposed to cold, hard block work, a visitors’ centre can become more accommodating. It could, in fact, be easily argued that the hard architecture of the prison itself is more intimidating than the individual pieces of equipment that make up the security. This is especially true for children; the impact of bright colours and different textures can communicate how an area is made for children to feel comfortable. Similar philosophies could be utilised in visitors’ centres where families are present[20]. As stated earlier, the expectation that children be still and silent for the duration of the visit is slightly unrealistic. However, if a space were created with the intention of encouraging children, the overall impact may be to the benefit of the visitor and the family also. The quality of this experience for younger families cannot however be enhanced solely by use of architecture. Operator philosophies must work in unison with the architecture to encourage the joy of the children, which in turn will create a pleasant experience for their families.

3.4. The Children’s Hospital

- The final of the three case studies is the children’s hospital. When discussing a building type that needs to be secure and yet feel positive and encouraging, it seems that the children’s hospital is the perfect candidate[22]. Not only does a children’s hospital have visitors across all cultures and social groups, but it also requires that children are essentially restrained from leaving[23]. Whilst obviously different from a prison, comparisons can be made and similarities drawn when discussing how to cater for visitors and encourage a positive response from youth. The children’s hospital has a unique ability to mask its actual function through architecture and that is what makes it such an appealing case study[24]. Whilst the same could be argued for an adult’s hospital, the children’s hospital allows for a direct correlation to research on children's experiences in prisons. This in turn allows for direct comparisons and applications to be applied more accurately than would otherwise be possible with an adult hospital.There are three main groups that a hospital caters for: patients, visitors and staff[23]. The basic needs of the child patient are to receive health care and recover comfortably without boredom. The needs of the visitors are to know that their child is safe and comfortable and that they too can be comfortable visiting them[22]. The needs of the staff are to ensure that patients can be treated as effectively as possible and to have sufficient space to ensure this is possible. They require that the patients are comfortable but also secure in their designated locations. Ultimately, however, the main needs of all groups within the hospital system are the same: to ensure the recovery of the patients. This recovery could be compared to the rehabilitation some prisoners experience through the love shown by their visitors. It has also been argued by some that prisons should be used solely as a form of rehabilitation[25].In regards to security, hospitals function almost exclusively using a combination of two systems: CCTV and natural surveillance by staff. CCTV is in no way an exclusive concept. If a person were to visit a location that required even minimal security, they would probably notice a security camera of some description. The use of cameras allows people to be surveyed and can be used to locate an offender once they have committed a crime. CCTV can also act as a deterrent for those who may be considering committing a crime[26].Natural surveillance in a hospital is very important. Medical zones are typically ‘guarded’ by nurses at their stations. Nurses’ stations are typically centrally located on each wing and overlook the majority of the floor, including most rooms and the central medical facilities. Medical supplies are typically accessed by staff using restricted access doors[23]. Whist prisons and hospitals may be similar in their secure functions, the area of interest in this case study is the way in which children’s hospitals have been approached in their design in recent years. Below are images from different children’s hospitals. Figure 1 is from the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, Michigan and Figure 2 is the Mercy Children's Hospital Cardinals Cancer Center in St. Louis and Figure 3 is Evelina’s Children’s Hospital in London. In these images one can almost instantly see the architectural intent. In an article responding to hospital architecture, Gibbs[27] stated that ‘there is a growing belief in health architecture that if the patients have a positive environment, there is a faster recovery time.’

4. Discussion

4.1. Guidelines for a New Visitors’ Centre

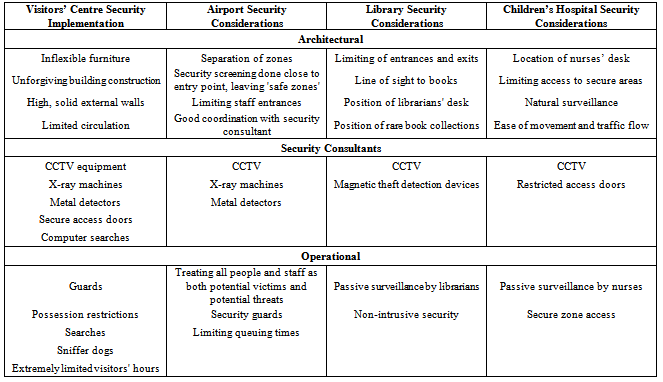

- In the table 1 a summary of discussed typologies is provided, identifying the main design approaches in terms of architectural expression, security and operational principles. Initially, comparisons shall begin on a larger, primarily architectural scale and then progress to smaller details and operator philosophies.

|

4.2. Architectural Expression

- Architecturally, a prison is not what one would describe as pleasant. Its design is ultimately to house prisoners and stop unauthorised persons getting in or out. In order to achieve this, prison fence systems are large and intimidating without apology; these often are cost effective and not too elaborated solution. They typically feature chain mesh and barbed wire and allow views inside the prison to buildings that are harsh and strong in construction.

| Figure 4. JThomas, “Perimeter fence, Linholme Prison” uploaded on geograph.org.uk on the 22/05/2011, Creative Common License, http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2422162 |

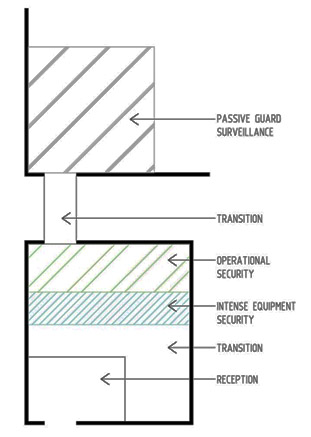

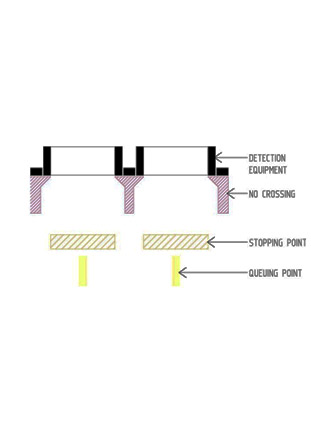

4.3. Security Screening

- From the airport case study, it was suggested that all security searches and protocols were conducted prior to entering the building in order to create a sterile or safe zone[12]. Typically, in the prison system, security checks are conducted immediately prior to entering contact with the prisoners. Visitors wait patiently in one building until such a time as they are escorted in groups to where the prisoners await them. These groups are then scanned via metal detectors, sniffer dogs and by guards before being allowed entry. This can cause delays for some groups whilst other visitors are being screened. It seems feasible then that as people begin arriving at the centre, the bulk of screening can take place at the point of arrival. From here, they can be transported to a waiting lobby with a view into the visitors’ hall. Between them and the hall can be minor security systems for peace of mind. A proposed scheme for the security screening zones can be seen in Figure 5. According to Dixey and Woodall[2], a regular issue involves delays into the visitors’ hall. Because visiting hours follow a strict schedule, if there are delays in security measures, then time is deducted from the visit itself. Floor guidance systems can be used to minimise queuing as they are utilised in the hospital and the airport and seen in Figure 6. Combined with gentle guidance from the guards, this system allows visitors swift entry to maximise their time with the prisoners.From the airport case study, we establish that the important feature of security is not so much the size of the machine but rather how it functions, what delays it causes and the impacts involved in waiting for it. Prison equipment tends to vary from prison to prison. Custom details are created for each prison, which means that there is some flexibility in what an architect can do to design them. Whilst they will obviously need to comply with prison operators’ regulations and security requirements, it may be possible to continue to maintain the same level of security without such massive pieces of equipment.

| Figure 5. Guidelines for security screening zones |

| Figure 6. Guidelines for floor symbols to assist with transition |

4.4. Colour

- Colour shall also be utilised as an important factor, particularly where children are involved. As seen in the case study of both the hospitals and the library, colour is featured primarily to encourage children and can in turn be justified for similar use in visitors’ centres. Family interaction should be encouraged if the testimonies by Dixey and Woodall[2] are to be believed, and by making the visitors’ centre a more family-friendly place, this goal can be achieved. Whist it is accepted that colour is beneficial in regards to children, it is by no means limited to areas with children as adults also benefit from colour. Variations in use however, would be evident. In Figure 1 and 2 for example, we see the use of colour is deliberately intended for children. In an adult hospital, the room layout and colour could still be applied, though their use would be more subtle in terms of stuffed toys and furnishings.

4.5. Views and Natural Light

- The emphasis on natural light and views is also something that can be utilised from Figure 1 and 3 and applied for general usage. If we observe the image, the influence of natural light is quite evident, providing the room with a calm and relaxing feel. Contrastingly however, in many visitors’ centres, high walls have been erected around the external seating areas in the name of security. Obviously, security is an important feature, however, there are other ways it can be achieved that allows for external views. For example, whilst still using solid columns for support, panels between could be made from toughened glass or polycarbonate to allow people to see out into the surrounding areas. Surrounding vegetation and greenery is ideal, as can be seen in Figure 1, however this may be situational due to the location of the prison. The impacts of various structural elements on natural lighting can also be seen in Figure 3. Whilst this type of space can be justified in the hospital, it would seem that the money spent on structural work and compensating for glass integrity may be socially unacceptable in a visitors’ centre. The concept of light, however, still remains important in softening the atmosphere.

4.6. Softening the Architecture

- Architecturally, furnishings and materials can be very important in determining the type of atmosphere a building will have[24]. The majority of prisons have steel toilets that are almost indestructible in an attempt to prevent prisoners damaging them. In recent times however, there are theories circulating to suggest that hardening architectural features intentionally may have an adverse effect and be seen as a challenge. Many newly refurbished prisons are now contemplating providing prisoners with the same toilets seen in an average house. This notion can also be applied to the visitors’ centre not so much on the theme of toilets but rather furnishings and materials[8]. At present, most visitors’ centres have fixed furniture spaced evenly to maximise space. Whilst very functional, there is no allowance for flexibility and customisation. It remains very regimented and similar to the system in which the prison is run. Whilst the importance of security is understood, flexibility may assist in ensuring comfort for visitors and removing the strict feeling of the prison. The concept is similar to those discussed earlier in the children’s hospital whereby the design should make people feel as if the visit were taking place under better circumstances.

4.7. Separation of Zones

- The idea of the children’s hospital could be taken a step further in its application to the visitors’ centre. The idea of separating children’s hospitals from adults’ hospital in itself has some merit. It seems that the main reason guards are strict regarding the control of children was as to not distract other prisoners and their visitors[2]. This is understandable of course as most adults can decipher when they are being loud and distracting whereas a child, particularly a young child, cannot. It seems feasible in this case that two zones within the centre be provided: one for those with children and one for those without. The two zones can be designed accordingly and separated by acoustic barriers to allow for more freedom of childish expression. Whilst the designer would need to consider how this could function securely in terms of access and circulation, the idea itself warrants consideration.

4.8. Existing Considerations

- There are certain aspects of the current visitors’ centre system that should not be changed. In the library case study, it was established that natural surveillance by the librarians was a significant security feature; the same applies for prisons. Prisons are designed to deliberately ensure that all areas are visible to guards and the areas that cannot be are surveillance by CCTV. This is an aspect of the current system that should not be changed. Whilst it is not likely a prisoner would commit a criminal act during a visit, when it comes to the safety of the visitors, surveillance by guards should be maintained at all times.The current models of security equipment could also be maintained without a great deal of negative consequences. As was explained earlier, the equipment itself is not the main cause of intimidation and its effects can be counteracted by altering the design of the centre and adjusting the time when the screenings are conducted. These alterations, coupled with positive attitudes from guards can significantly decrease the impact of heavy screening.

5. Conclusions

- Through initial research into the prison visitors’ centre, a number of factors were concluded. Firstly, it has been almost unanimously accepted that visitors have a positive impact in regards to helping prisoners rehabilitate[1, 3, 4]. This, in turn, not only benefits the prisoner and their family, but also society in general. Whilst this may be accepted, there is little research into how visitors are impacted by prisons and how they can be encouraged to come and visit. Because of this, three case studies have been analysed in an attempt to identify how some institutional typologies have been recently rethought to provide a more user-centred approach[13].Concerns about security seems to be the only principle adopted in the design of prison visitors’ centre; Sterile architecture as well as intimidating use of technology and inflexible procedures characterise this space affecting what should otherwise be the pleasant experience of meeting a relative or a friend. The discussion of the cases selected has provided indication about how a pleasant environment can be designed without compromising its security or level of control. More than drafting a new typology, this paper has provided a discussion of how a different design approach can achieve better secure environments in terms of users’ experience; subtlety and design can be unified to create a pleasant, appealing and non-intimidating space.Literature provides extensive resources about the design of libraries, children’s hospitals as well as airports; the design approach implemented in these typologies, as discussed in the paper, could be adapted to prison visitors’ centre. The solutions presented are quite general and common, but these have generally been seen as not appropriate for secure environments. The cases selected argue the opposite; a secure environment does not need to be hash and unwelcoming unless this is explicitly intended.Visitors are usually innocent victims of unfortunate circumstances and do not need to be treated with intimidation tactics and contempt. Their circumstances mean that daily life is difficult enough without needing to worry about visiting their incarcerated partners and being greeted with a ‘secondary prisonization’ experience. The benefit to society that these visitors provide has been demonstrated and it is the duty of architects, guards and prison operators to ensure that these visitors are not treated as if they were criminals themselves. The prison should remain secure; this is not debatable. However, as seen from the case studies above, there are other methods that can be implemented in an attempt to create a better visitors’ centre and a more humane atmosphere for its users.

References

| [1] | Wilkinson, R.A. and T. Unwin, Visiting in Prison, in Prison and jail administration: practice and theory, P.M. Carlson and J.S. Garrett, Editors. 1999, Gaithersburg: Aspen. p. 281-286. |

| [2] | Dixey, R. and J. Woodal, Moving on: An Evaluation on the Jigsaw Visitors’ Facility. 2009, Leeds Metropolitan University: Leeds. |

| [3] | Murray, J., The effects of imprisonment on families and children of prisoners, in The effects of imprisonment, A. Liebling and S. Maruna, Editors. 2005, Willan: Cullompton, UK Portland, Or. p. 442-492. |

| [4] | Hirst, J., The Australian Experience: The Convict Colony, in The Oxford history of the prison: the practice of punishment in western society,, N. Morris and D.J. Rothman, Editors. 1995, Oxford University Press: New York. p. 235-265. |

| [5] | Codd, H., In the shadow of prison; families, imprisonment and criminal justice. Reference and Research Book News, 2008. 23(3). |

| [6] | Aungles, A. and C. University of Sydney. Institute of, The prison and the home: a study of the relationship between domesticity and penality. Vol. no. 5. 1994, Sydney: Institute of Criminology, University of Sydney Law School. |

| [7] | Comfort, M., Doing Time Together : Love and Family in the Shadow of the Prison: Love and Family in the Shadow of the Prison. 2009, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. |

| [8] | PACT. Prisoners - families - Communities - A fresh start together. 8 July 2013]; Available from:http://www.prisonadvice.org.uk/about-us/our-goals-and-values. |

| [9] | Ferro, J., Prisons. 2011, New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc. |

| [10] | Pollock, J.M., Prisons: today and tomorrow. 2006, Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett. |

| [11] | McComb, M., Library security. 2004,[Cerritos, Calif.?]: Libris Design Project. |

| [12] | Kraal, B., V. Popovic, and P. Kirk. Passengers in the airport: artefacts and activities: ACM. |

| [13] | Suresh, M., D.J. Smith, and J.M. Franz, Person environment relationships to health and wellbeing: An integrated approach. IDEA Journal, 2006(2006): p. 87-102. |

| [14] | Woodall, J., et al., Healthier prisons: the role of a prison visitors' centre. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 2009. 47(1): p. 12. |

| [15] | Transport Security Authority, Recommended Security Guidelines for Airport Planning, Design and Construction. 2011, U.S.D.o.H. Security. |

| [16] | Horonjeff, R., Planning and design of airports. 2010, New York: McGraw-Hill. |

| [17] | Kirschenbaum, A., et al., Airport security: an ethnographic study. Journal of air transport management, 2012. 18(1): p. 68-73. |

| [18] | Jones, P. The Threat Within. 2010 6 August 2010 ]; Available from:www.airport-technology.com/features/feature62043. |

| [19] | Carey, J., Library Security by Design. Library & Archival Security, 2008. 21(2): p. 129-140. |

| [20] | Smith, K. and J.A. Flannery, Library design. 2007, Kempen, Germany: teNeues. |

| [21] | W.F.O. Committee. Account for Functional Needs. 2009 6 August 2010 ]; Available from:http://www.wbdg.org/design/account_spatial.php. |

| [22] | Bestak, D. and K. Seso, Safety of Children in Hospital. PEDIATRIC RESEARCH, 2010. 68(Journal Article): p. 620-620. |

| [23] | Grunden, N., C. Hagood, and I. Books24x, Lean-led hospital design: creating the efficient hospital of the future. 2012, Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis/CRC. |

| [24] | Biddiss, E., et al., The design and testing of interactive hospital spaces to meet the needs of waiting children. HERD, 2013. 6(3): p. 49. |

| [25] | Ruggiero, V., The country of Cesare Beccaria: the myth of rehabilitation in Italy, in Comparing prison systems : toward a comparative and international penology, N. South and R.P. Weiss, Editors. 1998, Gordon and Breach Publishers: Australia. p. XX, 488. |

| [26] | Smile, you could be on hospital security camera: Late Edition, in Illawarra Mercury U6 -. 2001: Wollongong, N.S.W. p. 14. |

| [27] | Gibbs, K. Architects to fix Hospital Ailments. 2010 31 August 2010 ]; Available from:http://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/Article/Architects-to-fix-hospital-ailments/431793.aspx. |

| [28] | Aiken, K. and D.C.f.D.R. University of California, Healing Environments: A Collection of Case Studies. 1995: Center for Design Research, Landscape Architecture Program, Department of Environmental Design, University of California. |

| [29] | Tufo, C.d. Helping Children Express Emotions.[cited 2013; Available from:http://lendinghandresources.com/helping-children-express-feelings-emotions/?goback=.gde_3739207_member_203676841. |

| [30] | Blakely, E.J. and N. Ellin, Architecture of fear. 1st ed. ed. 1997, New York :: Princeton Architectural Press. 320 p. :. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML