Kawshik Saha1, Rezwan Sobhan1, Afsana Alam2

1Department of Architecture, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet, 3114, Bangladesh

2Department of Architecture, Leading University, Sylhet, 3100, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Kawshik Saha, Department of Architecture, Shahjalal University of Science & Technology, Sylhet, 3114, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

With growing interest in sustainable practices in architecture, different approaches to sustainability have emerged. Now we are witness of the early revolutionary stages that will shape the future of human habitat .The cultural component of sustainability may be not a new concept and is part of the triple bottom line theory which is now a days quiet established. This study aims to find out the sustainable issues which have shaped the architecture of Sylhet city and to find out the cultural determinants of this sustainable building design practice. The outcome of the research will definitely help future designers and researcher to have a preliminary conception on sustainable issues of architectural design practiced in Sylhet and that will influence them to translate the traditional technologies in contemporary society. This research can serve as an important projection for future designers of a contemporary society as well.

Keywords:

Sustainability, Architecture, Critical Regionalism, Sylhet City, Culture

Cite this paper: Kawshik Saha, Rezwan Sobhan, Afsana Alam, Assesing Sustainibility as a Cultural Practice in Architecture: An overview of Sylhet City, Bangladesh, Architecture Research, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 36-41. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20130303.03.

1. Introduction

Throughout history architecture has played a crucial role in helping to define humanity’s relation to its larger surroundings. Architecture has not merely been a means for providing shelter, but has operated as a constructed model of a larger order; a vehicle embodying the temporal and cosmological understanding of the world in which we live. As such, architecture has the potential to bridge between the practical and the transcendent, playing both a practical and a symbolic role. In this sense architecture can play a pivotal role in the larger paradigmatic movement of sustainability. Each community produces its own architectural forms and techniques, evolved to meet the challenges of a unique set of conditions[1]. Thus Sylhet has its own traditional urban fabric with specific types of vernacular architecture. Sylhet, as a historic city that is more than thousand years old as a commercial hub, which explains its original namesake as ‘Sree Hotto’[2] means beautiful market place[3] As the history of Sylhet is more than thousand years of old there are many historical sites in and around the city. According to Sheltech-EPC Survey Report 2010, the proposed structure plan shows an area of 85 sqkm and present area of the town is 57 sq-kms[4] which was 8.42 sq-km[4] from 1878 to 1991. So, the core and rapid growing part is still limited within 10 sq-km. This part was the old town which experienced pre Mughal, Mughal and Colonial rule[5] The Sylhet can be considered as a museum of different architectural style including vernacular, colonial, modern, tribal and contemporary house forms. However, there are many rural features interwoven into the urban fabric of sylhet[6]. The objective of this research is to reveal the significant sustainable features which have been adopted through architect in the rural built form located in the Sylhet region.The out come of the research aims to give a preliminary study to gain an understanding of the building practised in Sylhet in deferent timelines. This investigation aims to redefine sustainability in context of culture rather than climate or technology. This study gives an overview of some some sustainable issues which are also now became cultural components. This research can help future designers and researcher to have a primary conception on sustainable issues of architectural design that will influence them in future to translate traditional technology to contemporary society.

2. Methodology

This study is comparative ‘case study research’ based architectural projects with cultural significances selected from different timeline. Based on Yin’s definition,’ Case study is an empirical inquiry that investigates a phenomenon and settings’[7], the projects were investigated to reveal their response towards the existing condition.These selected projects include vernacular to neo modern, colonial to contemporary, rural to urban. Each of the structured was assessed on some common features including climatic consideration, environmental responsive ness, spatial planning, energy issues, water management etc. At the end projects finins were compared to get some common issues practised in most of the structures. These issues can define social and cultural sustainability which shaped the form. Preliminary data were collected from site survey. Theoretical data were collected from previous research documents on Sylhet city.

3. Architectural Sustainability: Some Issues

3.1. The Role of Culture Defining Sustainibility

Without cultural awareness, any attempt to create a more sustainable environment is likely to falter as it encounters but fails to recognize very deeply structured personal responses to particular places. Guy and Farmer[8] conclude that “Contemporary architecture should therefore seek a greater understanding of local culture if it is to be sustainable.” This view is further supported by the notion that to be truly sustainable, buildings need to remain relevant and functional to the community they serve over the long term. Energy efficient buildings that fail to address cultural needs and values may suffer premature obsolescence and invite major modification or outright demolition and replacement. Vale and Vale[9] have argued that “One way to achieve longevity and avoid demolition is to design buildings that are capable of adapting to the users’ changing needs.” McDonough and Braungart[10] address the notion of being “native” to a place, implying the more holistic relationship to local context, and by extension to the larger ecosphere.

3.2. Vernacular Sources of Sustainability

Even from the narrow perspective of energy consumption, fundamental design strategies such as building orientation, location and nature of fenestration and viability of alternative energy sources (solar collection, wind generation, ground source heating) must all be closely attuned to local climatic, microclimatic and geological conditions if they are to perform effectively. At a more strategic level, procurement of locally available materials and regional construction practices taking advantage of local labor skills also constitute effective strategies for reducing the ecological footprint of construction projects (Fig 1). It is in Sylhet, where a tropic climate, geographic isolation of settlements and limited access to technology demanded the development of vernacular responses—in both indigenous and early settler architecture—very carefully attuned to local conditions.

3.3. Critical Regionalism and Sustainable Architecture

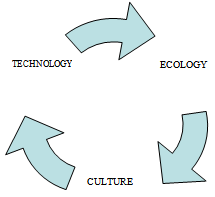

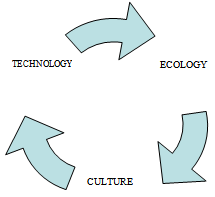

A critical re-reading of Frampton’s essay - “Culture Versus Nature: Topography, Context, Climate, Light and Tectonic Form”—Mcminn and Polo[11] suggested the possibility of a discourse on sustainable design that reaches beyond its traditional energy-efficient confines. Many of the elements described by Frampton lend themselves to the pursuit of an architecture whose responsiveness to local conditions leads not only to greater energy and material efficiencies, but that also address local cultural mores and tectonic traditions, leading to not only greener but also more meaningful architecture. | Figure 1. Dynamic Model for sustainability |

With this construct in mind, it is possible to begin to articulate a theoretical basis for sustainable architecture that brings the discourse outside of the simulation lab and into the mainstream of critical practice. This serves as a potentially important model for a contemporary architecture that adopts strategies of sustainability related to local climatic and geographic conditions, cultural practices and mores, but that also participates in a broader critical discourse by engaging sustainability not only as technique or method, but also as a cultural paradigm.

4. Interpreting Sustainability in Architectural Built form

In their article “interpreting Green Design: beyond performance and ideology”, Simon Guy and Graham Farmer[12] argue that there are two general models of analyzing sustainable architecture: Most common method is to view the diversity of design strategies as “distracting” to the necessity of comparing measurable data on issues such as climate change. And the second approach, believes that the diversity of green architecture is due to the different ideologies and philosophical beliefs held by the actors involved. Here Guy and Farmer[12] suggest a third model which “recognizes the interpretative flexibility of the sustainability concept” (p. 11). There are three main points in their discussions:1. There is gap between the definition of green buildings and the actual practice of sustainable architecture as a “complex and contextual social phenomena”. This approach is the pragmatic one that Moore[7] suggested in non modern regionalism.2. They argue that these diverse strategies do not simply materialize from a pre given definition of “greenness”. Instead, they are shaped through a combination of different philosophies of green design in a particular context. 3. They also emphasize the need to understand contexts of sustainable architecture and link the various technological pathways to the local context, which is one of the main features of Non modern regionalism

5. Six Logics of Sustainable Architecture

Guy and Graham Farmer[14] developed the three models of Performance based, Ideological based and Hybrid models further and proposed six “logics” of sustainable architecture used as a typology for analysis of environmental logics. Guy and Farmer point out in their proposal is that these logics may overlap and interact, and they are by no means “frozen in time or space”. Therefore the categories may merge, collide or even be absent in practice. Each of the logics present the ways in which the debate is shaped differently upon various interpretations of environmental problems.| Table 1. six logics of vernacular architecture by Guy and Graham Farmer (2001) |

| | Logics | Image of Space | Idealized concept of space | | Eco technique | global contestmicrophysical | integration of the global environmental concerns into conventional building design Urban vision of compact and dense city | | Eco centric | fragilemacrobiotic | Harmony with nature through decentralized autonomousBuildings with limited ecological foot prints.Ensuring the stability, integrity, and flourishing of local and global biodiversity | | Eco aesthetics | Alienatinganthropocentric | Universally reconstructed in the light of newEcological knowledge and transforming our consciousness of nature. | | eco cultural | Cultural contextand regional | learning to "shell" through building adapted to local and bioregional, physical and cultural characteristics | | Eco medical | Pollutedhazardous | A natural and tactile CM environment Which ensures the heath, wellbeing .end quality of life or individuals. | | Eco social | social contexthierarchical | Reconciliation of individual and community in socially cohesive manner trough decentralized organic nonhierarchical and participatory communities |

|

|

6. Project Examples: A Case Study based Analysis

6.1. House at Ambarkhana, Sylhet City

Type: Traditional residential structure of Urban Sylhet. This is a 120 year old residential house(Fig 2 & 3) located near the Amberkhana point in Sylhet city heart. Now the house is used as an official function as a rent basis. The house is an excellent example of local vernacular house form located in Sylhet city. This house contains a compact configuration of forms with pitch roof. Different modules and spaces are connected and had a compact looking form. The form is elongated east west and facing south. The entry approach is defined by a shaded semi outdoor space. The house includes a inner courtyard for using it for household needs. An internal semi outdoor shaded circulation is connecting the different rooms of the house. The most dominating part of this house form is connected pitched roof of different heights. Roofs manly oriented east west side are not dispersed but connected with each other to define various functions inside. The roofs are made of tin which indicate the ratio of heavy rain fall in this area. The external and internal walls of this house are made light weight. Each wall contains three feet high brick wall and bamboo maid cement plastered wall attached to it. These walls help to reduce building weight and climatically work as good insulator. The contraction technique was based on free fabricated assembling on site. The building needs regular maintenance and life cycle not too high. But all the building materials are rescale and environment friendly.  | Figure 2. Vernacular House located in Ambarkhana Sylhet city |

| Figure 3. Vernacular House located in Ambarkhana Sylhet city |

6.2. The Sylhet Central Hospital, Sylhet City

Type: Public Colonial Structure Built in Brtish Raj in Sylhet city.This is a 100 year old hospital building house(Fig 4 & 5) located near the chauhatta point in Sylhet city heart. Now the building is used as a dormitory of the medical college students. The house is an excellent example of British colonial architecture with local archetypes. The colonial style has been blended with native building features. This building complex is a rectangular shaped form with a large open space in heart. Four linear symmetrical built forms are connected in their corners to form the rectangular shape. The main entry in the complex faces the west side with typical symmetrical colonial approach. The building is single storied with pitched roof over it. The roofs are made of tin which indicate the ratio of heavy rainfall in this area. The external and internal walls of this building are made of heavy thick brick wall. These walls carry the major structural load as well as act as a good thermal insulator. The major circulation way is a semi outdoor space which connects all the spaces, perhaps this semi shaded circulation way integrate all the four individual buildings. The contraction technique was based on typical masonry construction technique. Another major climatic feature introduced in this building is rain water harvesting. Rain water is collected and reused for cleaning purpose. | Figure 4. Old hospital located in Sylhet city, Colonial style blended with rationality |

| Figure 5. Old hospital located in Sylhet city, Colonial style blended with rationality |

6.3. A house of Indigenous Khasi Community, Duncan Tea Estate, Sylhet

Type: A residence of Ethnic Tribe members. Sylhet is a land of regional cultural variety of different ethnicity not only for main stream Bengalis but also for various indigenous or tribal communities. So architecture of these tribal communities is a great example of regional ethnicity as they are directly responsive with local microclimate and topography. This house(Fig 6 & 7) is located in a 100 years old Khasi Settlement. The settlement is spread on a hill top. The house on a stilt platform is rested on bamboo poles. This is a key regional feature of hilly topography. The pitch roofed built form covers most of the wall surface for shading from sun and protection from rain. A major part of this form is the wide veranda or semi outdoor .This act as an entry approach and connect the home with the common circulation of village people. The walls are made of burned brick and the wood made bamboo stick frame. Walls are plastered with mud or cement. These houses have very similar technique like the vernacular house form located in Sylhet city. All the house form has a backyard for household works. The space under the floor platform is often used as storage. This indigenous form is not only environmental responsive but also support the socio economic livelihood of this ethnic society. For them this is more than a house; this is a symbol for cultural ethnicity | Figure 6. A house of Indigenous Khasi Settlement in Double Chora,Sylhet |

| Figure 7. A house of Indigenous Khasi Settlement in Double Chora,Sylhet |

6.4. The house of P S Chowdhury, Halderpara, Sylhet

Type: A modern Residential house.This is a residence (Fig 8 & 9) designed by Architect Rajon Das. He is one of those architects who are trying to reestablish vernacular features and integrate these regional archetypes with contemporary architecture practice. This residence is a duplex including all the residential facilities distributed in both floors. The structure is built in beam and column structure and both internal and external column are made of open face bricks without plaster. The low cost attitude and local microclimate inspired architect to use pitch roof as a major structural element. Exposed brick act as a good thermal insulator. Large openings are for proper ventilation. Rainwater spout for rain water drainage. Large semi outdoor space is directly inspired from traditional local vernacular architecture. Low cost technology and microclimatic features are adopted by contemporary architect to create this architecture with regional identity. | Figure 8. A contemporary house located in Syhet city designed by Ar.Rajon Das |

| Figure 9. A contemporary house located in Syhet city designed by Ar.Rajon Das |

7. A Model for Sustainable Practice

The examples cited above are chosen from four distinct cultural and geographic area of Sylhet city, the teagarden area, the hilly indigenous settlement, the city center and suburban area. The climate, geography and cultural heritage of these locations differ widely, resulting in highly particularized architectures which, in varying ways, marry contemporary technological building practice with unique local conditions. The review of the case studies indicates some key features which leads to a possible sustainable practise in building construction in Sylhet city.T hese design considerations also responds to the research question of this research that hoe buildings response to the settings. These examples of different architecture speak with a polyphonic voice which is nuanced, layered and complex, reflecting Kohler’s statement[15] that “There is no conflict between regionally appropriate and environmentally appropriate building practice” as well as Frampton’s call[16] for “a high level of critical self consciousness in his proposal for Critical Regionalism. This study clearly shows that some typical sustainable features are carried out by all the buildings from different conditions and types. The main stream of dwelling architecture in Sylhet region is clearly rooted in vernacular forms. Nowadays these vernacular forms are often found in the midst of other buildings ranging from simple wooden structures to modern brick dwellings. Where they are found, they often still have a function in the maintenance of the traditional culture.1. Water management system 2. Harmony between nature and environment 3. Building construction systems and building materialsSocially this spatial specification results in distinctions and gradations of space from:1. Private to public;2. Male to female;3. Sacred to profane;4. Low status to high status;5. Consanguinal to cognatic relationships; and6. Group to elementary family.| Table 2. Sustainable Features applied in building technology in Sylhet Region |

| | Issues of sustainability | Responsive application in built forms | | Energy Efficiency | Passive solar design strategies are applied in construction ,Extensive use of shading devices, double roof attics, use of low energy materials are key thermal design policies. | | Material Culture | Used construction technique of tropical area, modular method, prefabricated construction, true expression of local craftsmanship. | | Water Management | Compact house planning, pitched roof for rain water protection, Rain water harvesting methods applied in roofs.Wide semi outdoor used as shaded courtyard for agricultural household need. | | Spatial relation | Open space between houses, vegetation, Community and cultural activities focused on outdoor. Frequent sequences between indoor and out door. Larger semi outdoor present., | | Seismic Stability | Light weight structure, Base isolation technique, Post lintel frame structural skeleton are used. | | Economy | Exposing economic status of owner of both higher and lower income group. Scope for household up gradation with needs. | | Society and culture | Strong regional expression.Sense of privacy, gender Issues are present. Built forms are responsive to community neighborhood. |

|

|

The data collected from case study survey was analyzed . Some issues of sustainability were found which is commonly practiced in most of the structures. Responsive design applications by the builders to the specific parameters were analyzed too. Based on the data collected data from case study the following table was made to understand the common practice in construction culture in Sylhet city responding a specific parameter like energy efficiency, material culture, water management and others.The case study shows the key regional issues which architecture must follow for its sustainability. This issues are more climatic or environmental but much more cultural. Practice of sustainability is a cultural practice here. The projects included in this study suggest an approach that may prove to be among the most effective strategies for advancing the cause of architecture that is sustainable at a number of levels, fulfilling its role not only as environmental mediator but also as a cultural project.

8. Conclusions

The objective of this research was to gain an understanding on issues of sustainable practice carried out through out the years by indigenous builders in Sylhet city. This is a preliminary effort only and further research needed to find out more sustainable features in building practise in Sylhet city. The researchers hope this study will inspire future architect and researchers, innovators to find some sustainable design solution which is compatible for modern day construction. Though this study this can be summarized that sustainability practice in locally built environment is a common phenomenon in sylhet city and this practice is more cultural than others aspects while these features common features are making bridge between tradition and modern practice. Researchers also believe that translating these vernacular technologies in contemporary construction can help for future sustainable design process.

References

| [1] | Cooper, I and Dawson, B Traditional Building of India, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London. (1998). |

| [2] | Choudhury, A.C Sree hottor Itibrito, Culcutta. (1910). |

| [3] | Bangla Pedia The Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society, Dhaka. (2007), |

| [4] | BBS,. Bangladesh Population Census. Urban Area Report, Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Government of Bangladesh. 2001. |

| [5] | Ahmed, S. U. Urban Growth and Development of Sylhet Town: Colonial Period, Sylhet: History and Heritage.Dhaka: Bangladesh Itihas Samiti; 1999. |

| [6] | Islam, N. Sylhet City: Urban structure and Urban Development Planning, Sylhet: History and Heritage. dHAKA: Bangladesh Itihas Samiti; 1999. |

| [7] | Groat, L. and Wang, D., Architectural Research Methods, john Willy & sons Inc,2002,ISBN 0-471-33365-4 . |

| [8] | Guy, S., and Farmer, G., Reinterpreting sustainable architecture: The place of technology,Journal of Architectural Education 54(3) 140-148,2001. |

| [9] | Vale, B., and Vale, R., Design for a Sustainable Future, London: Thames and Hudson, 1991. |

| [10] | McDonough, William and M .Braungart, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the way we Make Things, New York: North Point Press, 2002. |

| [11] | Mcminn, J and Polo,M. ,Sustainable Architecture as a Cultural Project, The 2005 World Sustainable Building Conference,Tokyo, 27-29 September 2005. |

| [12] | Farmer G. & Guy S., Interpreting Green Design: Beyond performance and Ideology. Built Environment, Vol 28, No.1, 11-22, 2002. |

| [13] | Moore, S.,Alternative routes to the sustainable city: Austin, Curitiba, and Frankfurt. Lanham: Lexington Books,2007. |

| [14] | Guy, S., and Farmer, G., “Reinterpreting sustainable archi tecture: The place of technology”. Journal of Architectural Education 54(3) 140-148, 2001. |

| [15] | Kohler, Niklaus “Cultural Issues for a Sustainable Built Environment” in R. Cole and R. Loach , Buildings, Culture & Environment: Informing Local & Global Practices, Ox ford: Blackwell, p. 85,2003. |

| [16] | Frampton, Kenneth “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance” in H. Foster (ed.) The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, pp. 16-30, 1983. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML