-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2012; 2(6): 128-133

doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20120206.03

High Density High Rise Vertical Living for Low Income People in Colombo, Sri Lanka: Learning from Pruitt-Igoe

Thushara Samaratunga, Daniel O' Hare

Institute of Sustainable Development and Architecture Bond University, Australia

Correspondence to: Thushara Samaratunga, Institute of Sustainable Development and Architecture Bond University, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The Colombo Master Plan (2008) reveals that there are 66,000 households within the City of Colombo living in squalid slums and shanties unfit for human habitation. They represent 51 per cent of the total city population, and live in 1,506 pockets of human concentration identified as Under Served Settlements (USS) encumbering on state owned lands with no title. About 390 hectares of valuable prime lands in the City have succumbed to the encroachment process during the past five decades. Moreover they have engulfed all the environmentally sensitive low lying areas, canal banks and flood retention areas as well as roads, railway reservations and other open spaces. Since gaining independence in 1948, the Sri Lankan government has devoted much attention to finding a solution for this situation and has successively introduced policies, programs and projects to overcome poor housing in Colombo. However, most of these programs have proven to be only temporary fixes, and have not made any significant long-term impact to the housing sector overall. This research paper discusses the Sri Lankan government’s policy move towards high-rise high-density low income public housing as an appropriate solution for slums and shanties in Colombo City. It is noted that high-rise housing for low income people is not a universally accepted solution for housing for low income people and some countries have totally rejected high-rise for low income housing due to significant failures in the past. At the same time, some other countries claim success in high-rise housing for low income people including uplifting low income people to a middle income status through high rise housing. Therefore high-rise low income housing remains a controversial topic in many developed and developing countries. This paper revisits the literature on Pruitt-Igoe in order to identify lessons that may assist Sri Lankan authorities to avoid similar failures.

Keywords: High-Rise Housing, High-Density Housing, Low Income Housing, Low Income High-Rise Housing, Public Housing, Pruitt-Igoe, Urban Development Authority, Colombo

Cite this paper: Thushara Samaratunga, Daniel O' Hare, "High Density High Rise Vertical Living for Low Income People in Colombo, Sri Lanka: Learning from Pruitt-Igoe", Architecture Research, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 128-133. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20120206.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Colombo Master Plan (2008) reveals that there are 66,000 households within the City of Colombo living in squalid slums and shanties unfit for human habitation. They represent 51 per cent of the total city population, and live in 1,506 pockets of human concentration identified as Under Served Settlements (USS) encumbering on state owned lands with no title. About 390 hectares of valuable prime lands in the City have succumbed to the encroachment process during the past five decades. Moreover they have engulfed all the environmentally sensitive low lying areas, canal banks and flood retention areas as well as roads, railway reservations and other open spaces. Since gaining independence in 1948, the Sri Lankan government has devoted much attention to finding a solution for this situation and has successively introduced policies, programs and projects to overcome poor housing in Colombo. However, most of these programs have proven to be only temporary fixes, and have not made any significant long-term impact to the housing sector overallUntil the year 2001, high-rise low-income housing (structures above five storeys) was not on the Sri Lankan government’s urban planning agenda. Since then, the government has attempted to convince urban slum dwellers to relocate to nearby high-rise apartments and, thus, reclaim valuable land inhabited by informal low-income settlements in Colombo city. The “Sahaspura” high-rise low-income housing project was the first attempt in this direction and it consisted of 14 floors with 670 housing units in 2001. In practice, this concept has been limited to one project, Sahaspura, and no more developments were proposed until the end of the civil war in 2009. However, since the after end of the civil war in 2009, the Sri Lankan government has given priority to city development, especially in Colombo as it is the commercial capital of the country. The main constraint to Colombo urban and economic development was that 51 per cent of the city’s population live in under-served settlements. The alternative considered best by Colombo urban planners was to implement a high-rise high-density vertical housing strategy, which was begun in 2001 with the “Sahaspura” project. At the time of writing this paper, nearly 12,000 high rise housing units are commencing with a goal to construct 35,000 dwellings within the next three years[1].Sri Lankan housing professionals and policy-makers have mixed feelings about adopting high-rise low-income housing in Colombo. Lack of literature and research are the main impediment in the field and Colombo City needs more academic research to discover what the main factors are in the success or failures of low-income housing, especially high-rise low-income housing. Even though high-rise low-income housing is new for Sri Lanka, it is not new for many other countries in the world. Therefore, the knowledge gained from international experience and critical evaluation of past experiences, would be very beneficial for Sri Lankan high-rise housing.The Pruitt-Igoe public housing project in St Louis, US is one of the most discussed public housing projects as well as a symbolic icon and the most well-known case study, which ended in the demolition of 2,800 housing units[2]. There is a correlation between the Pruitt-Igoe case and the current Colombo high-rise low-income housing program entitled Relocation of Underserved Settlements, in that the main aim of both projects was slum clearance by providing high-rise housing for the urban poor. Therefore, understanding the Pruitt-Igoe experience is extremely important for Sri Lankan professionals and policy-makers to reduce the risk and not repeat the same mistake in developing high-rise low-income housing in Sri Lanka.

| Figure 1. Pruitt-Igoe high-rise public housing Project[15] |

| Figure 2. “Sahaspura” Low income housing Project[14] |

2. Main Issues Associated with High Rise Low Income Housing

- In critically evaluating the Pruitt-Igoe public housing project and other well-known high-rise public housing projects, it is clear that most issues fall into four main categories: 1) Social and cultural issues;2) Architectural, planning and technical issues; 3) Financial issues; and4) Management and operational issues. The success or failure of high-rise low-income housing depends on how these four sectors are managed and mitigated. After the high-profile failure of the Pruitt-Igoe public housing scheme, most housing professionals considered high-rise public housing no longer an option in the US. Therefore, to understand the issues surrounding high-rise low-income housing, it is worthwhile to conduct an in-depth evaluation of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project with comparison of how social and cultural issues, architectural planning and technical issues, financial issues and management and operational issues affected this project. Pruitt-Igoe was a large public housing project built in 1954 on a 57-acre site in St Louis, comprising of 33 eleven-floor buildings which would house over 2,800 apartments. The complex was designed by well-known architect Minoru Yamasaki, who also designed the World Trade Centre in New York. Pruitt–Igoe was a critically acclaimed design and in 1951 the Architectural Forum gave Pruitt–Igoe an award as the ‘the best high-rise apartment’ of the year[2]. Pruitt–Igoe was styled as a project that followed the principles of Le Corbusier’s concept in modern architecture. Although criticisms of inadequate parking and a lack of recreation facilities were levelled at this project, no one anticipated Pruitt–Igoe would become a symbolic failure in the public housing sector[3]. Shortly after its completion, this award-winning project began its decline. The project had failed on an architectural and social level. Maintenance and many other qualitative features proved to be expensive and difficult to upkeep. In 1972, state and federal authorities decided to demolish the $57 million investment project, making it the biggest disaster in high-rise public housing history[2]. What went wrong with Pruitt–Igoe? The explanation for the spectacular failure is complex. Many people believe it was purely architectural failure and the construction did not meet the needs of the city or its residents. Other critics bring in social factors, such as a lack of shared space to create community feeling and the lack of recreational areas. Some argue poor maintenance and management caused the building to fall into disrepair. However, no single reason could cause such a huge disaster, and the most common theory is that several mistakes were made throughout the project. According to Cohn (2005), Architectural social, management and policy issues equally led to the qualitative decline and kept people out of the project.

3. Architectural Planning and Technical Issues

- Pruitt-Igoe is famous among architects because its demolition was heralded as the death of modern architecture, and it came to symbolize a general loss of faith in architects’ abilities to design a solution to problems in general and high-rise public housing in particular[4 , 5]. Prominent urban planner Oscar Newman stated that “Architects love to build high-rise buildings because that’s what impresses other architects[and] most architects give priority to their personal goals rather than the real requirements of the project”[6]. The dialogue around iconic buildings and large-scale projects generates direct and indirect popularity for the architect. With Pruitt–Igoe, the initial proposal for a mix of high-rise, mid-rise and walk-up buildings, but the final result was 33 buildings, each with eleven floors – a considerably denser housing scheme[5]. Thomas P. Costello, the former director of the St Louis Housing Authority, said in an interview "The entire public housing program was always geared to production, not to providing decent housing for poor people"[6]. Costello believed that badly designed high-rise buildings, like those at Pruitt-Igoe, “virtually guaranteed failure”[6].Technical failures and the negative attitudes of the architects also had a very bad impact on public housing in this era. O’Neill[7] states “most of the architects who plan public housing for low-income people didn’t really care about the people who were going to live in it. The public’s image was they were just considered poor, illiterate people, so the attitude was, ‘Let’s put them all in one place, in these huge buildings, and just let the damned things go’[7]. That statement rings especially true in context of the Sri Lankan low-income housing, as governments tend to think only in terms of literal improvement of living space, believing is it enough to uplift the living condition and social life of the urban poor. For example, in “Sahaspura” the minimum unit size is 35 square metres, which is not much space for an entire family and their amenities. However as the family’s previous dwellings in the slums likely consisted of a space smaller than 35 square metres without any amenities, it is an improvement[8].According to Cohn[6], there are common features to high-rise public housing that mean it will not wear well over time. Some examples of these features are poor maintenance, the regular breakdown of elevators, a low-cost design, a lack of insulation to prevent excesses of heat and cold, a lack of open space and landscaping as well as isolation of individuals due to a lack of common space. Furthermore, if an area consists of only low-income people, then it will be labelled as ‘a place where the poor people are living’[6]. The Pruitt-Igoe development experienced all of the above-mentioned weaknesses, and they have been very common in most low-income housing projects in Sri Lanka. Location is another issue in many public housing projects. Planners tend to propose poor and isolated areas for public housing. Considering the land value and demand, locating public housing far from the city center is much cheaper and can reduce the cost of the project. Pruitt-Igoe, although located relatively close to downtown St Louis, was located in an area demarcated as a poor residential area. Fortunately, Sri Lankan urban planners have avoided locational mistakes by attempting to provide low-income housing near to the CBD and other workplaces. The best examples are Gunasinghe Pura Flat, just five minutes walking distance from the CBD; Central Sation Kotahena Flats, five minutes walking distance from the Colombo Harbour; and Maligawatha Flat, which is 10 minutes walking distance to the railway yards and industrial areas. In addtion Sahaspura, Sri Lanka’s first high-rise low-income housing project, is also located at the centre of the city. Prime location is one of the main strengths in Colombo low-income housing, and even though low-income housing tends to have minimal facilities and amenities, no project has resulted in demolition or mass vacancies like Pruitt-Igoe.Sometimes implementing innovative ideas and experiments also leads to a bad result for high-rise buildings. Pruitt-Igoe's recreational galleries and skip-stop elevators, once heralded as architectural innovations, became nuisances and danger zones[3]. From an environmental and sustainability point of view, the skip-stop elevator is a creative way to protect the environment and reduce electricity consumption. From a health point of view, reducing where elevators can stop encourages people to walk and climb stairs, thus receiving beneficial incidental exercise. However, a skip-stop elevator causes enormous difficulty to elderly people, sick people or those with a disability, pregnant woman and parents with small children – the very people who are often concentrated in low-income housing. Unfortunately, the same thing happened in Sahaspura when the Sri Lankan architects also incorrectly assumed that having galleries would help promote community interaction in what was bound to be a harsh social environment, and so the lift only operated above the fifth floor. Today, these huge corridors are the most difficult part to maintain and that unnecessary communal space could have been added to residential units for the same cost. Fortunately, the Sri Lankan architects did not structurally restrict the elevators, but simply manually restricted usage up to the fourth level. Therefore those people who need the elevator can obtain special permission to use it when they need[9], and elevator management processes can be reviewed in the future.

4. Social Issues

- The Pruitt-Igoe development made several mistakes in the social aspect of the project from the very beginning. Basic design negligence can cause massive damage to the entire social lives of the people who live in the project. Hoffman[5] said “The Pruitt-Igoe structures were very successful, but the designers ignored the very basic social requirements”.Regardless of income level, racial desegregation was another social issue in Pruitt-Igoe. Originally Pruitt-Igoe was conceived as two segregated sections, with Pruitt for blacks and Igoe for whites. However, attempts at integration failed and Pruitt-Igoe became an exclusively black project[2], with stigma arising from the negative social perception of the project as a poor black project. In Colombo, Sri Lanka, ethnic and religious diversification is not a big problem. Despite this, social recognition can be very negative and with a perception that low-income people who live low-income housing are ‘looked down upon’ and lack privilege in the city[9].Critics claim that another mistake made in Pruitt-Igoe was to house many people in too little space, without easy access to the world beyond the site[6]. Sociologists were warning of the dangers of isolating the poor in dehumanising structures, even as the US push for high-rise public housing got underway in the early 1950s[2]. A similar situation is currently occurring in Sri Lanka. Following the end of the 30 years civil war, planners and the Colombo City authority are attempting to build as many high-rise low-income housing units as possible in a limited area to clear the slums in the city. As with the US public housing push of the 1950s, Sri Lankan urban planners and policy-makers often pay more attention to housing production than to the social issues. If Sri Lankan policy-makers do not learn lessons from past unsuccessful examples of isolated high-density low-income housing, similar failures could happen in Colombo.Further social issues such as vandalism, illegal business, violence, drugs and organized crime also contributed to the failure of the Pruitt-Igoe development[2,6]. These types of social issues are not uncommon in slums and when slum dwellers relocate to the high-rises, they bring their existing social issues with them. Therefore, planners should be aware of this problem and avoid placing thousands of slum dwellers in one place, thus reducing their vulnerability to crime and creating a safe environment. In the 1980s the Max Plank Institute in Germany received funding from the European Union to establish the relationship between high-rise low-income housing and vulnerability to crime, focusing on whether this problem of crime has something to do with the design and construction of high-rise housing or whether it is to do with broader social and demographic factors[10]. The research found that crime and a decrease in the quality of life is not limited to high-rise buildings and that physical security and design improvements aimed at crime reduction alone will not in themselves guarantee a safer environment. Community safety is reliant more on socioeconomic conditions, community cohesion, demographic and estate management factors. Good design and appropriate levels of security can provide the setting for a better quality of life for residents of high-rise housing[10].

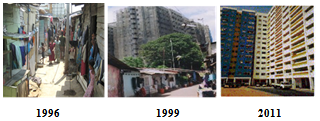

| Figure 3. “Sahaspura” Before, and After[14] |

5. Management and Maintenance Issues

- Experiences with the management and maintenance of high-rises in the past have shown that high-rise housing is difficult and complicated to manage, whether privately owned, government owned or belonging to a housing association. High-rise housing often shares too many facilities and amenities including public spaces, lifts, combined electricity and water networks, but lacks clear allocation of responsibility for the maintenance, management and cleanliness of the building. Therefore having a management corporation is essential for undertaking the management and maintenance of the building. It is vital that the management body has sufficient funds to keep the building in a good manner. Privately owned luxury high-rise apartment buildings have their own mechanism to maintain the building which includes adequate funding, but it more complicated when it comes to low-income high-rise housing. Poor maintenance is one of the biggest contributors to the deterioration of high-rise buildings and low-income housing associations often have little or no money to undertake regular maintenance. With the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, a decline of the occupancy rate and a difficulty in collecting rent from very low-income residents resulted in a reduction of the funds available for maintenance, which led to a decline in the quality of the building which in turn discouraged people from moving into the building. This situation is very common in Sri Lankan low-income housing where no one has taken responsibility for the maintenance of low-income housing. Low-income house-owners believe it is the responsibility of the government or city council and blame the government and city council for the deterioration of the building. The previous Sri Lankan government did not establish a requirement to have a management corporation for low-income housing projects and all maintenance was done by the Common Amenity Board in the Housing Ministry. However, this system has been changed since the Sahaspura project and now it is a legal requirement to establish a management corporation responsible for taking care of the building and supporting the residents of new high-rise low-income housing projects. However, even with a compulsory management corporation, raising funds is still critical. This problem is not exclusive to Pruitt-Igoe and Sri Lanka. It is a very common scenario for low-income high-rises around the world. Extensive research and critical dialogue has been done on this issue and a range of possible solutions exist. According to Daheragoda[11]:Renovation of high-rise low-income housing[in Sri Lanka] is often less expensive than building new housing. Most forms of low-income housing are difficult to manage. This, however, does not mean that there are no solutions at hand. The key is to be more creative, allow for more input from those who live in these developments and have experienced these problems first hand, and not seek to implement a single ‘successful’ model in all cases[11].

6. Financial Issues

- Mary K. Nenno, the Associate Director of the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials in the 1950s, stated that "The construction of high-rise public housing was to a large extent a response to cost pressures…. The federal government wanted to get as many units on a site as was humanly possible – not only because it would be cheaper to build per unit, but also because it would be cheaper to operate once it was built and would mean more rental income coming in”[6,12]. Accordingly, it was clear that under the urban renewal and slum clearance projects of the 1950s, the housing authority target was to provide as many units as possible for low-income families with a limited budget. Budget restrictions were one of the main reason changing the original proposal of Pruitt-Igoe, which was a mix of high and low density housing projects, to only high-density 11-storeyed housing. The Pruitt-Igoe project was also severely restricted by cost-cutting as an attempt to reduce costs from the original budget. The cost-cutting limited the architects and forced them to change the original designs. Several changes were made to the design of the Pruitt-Igoe public housing, for example elevators and corridors were constructed on the outside of most buildings and cheap material and poor-quality finishes were used. Additionally, to save money on doorways, elevators were designed to stop only on every third floor, and while the elevators and hallways constructed along the outside of buildings may have reduced initial costs, they also virtually ensured there would be maintenance problems. This post-concept reduction of construction costs also happened in Colombo while developing its high-rise low-income housing. The government wanted to minimise the cost of housing while building as many units as possible within a limited budget. In Sahaspura, the initial minimum unit size was 45 square metres. This area was reduced to 35 square metres due to the huge cost pressure and to increase the number of units. Currently the Sri Lankan government plans to construct 66,000 high-rise housing units in Colombo to relocate the residents of under-served settlements in the city. This is the biggest relocation programme in the country’s history and the estimated budget is LKR 2.5 million per unit (AU$24,000). Gotabaya Rajapaksha[13], the Secretary of the Ministry of Defence and Urban Development in Sri Lanka and the key person in the relocation of under-served settlement program, during a speech on World Town Planning Day (2010), highlighted that:At least Rs 2.5 million is required to resettle one of these families at a small housing unit. We have to find money to relocate these families. Town planning comes in here. Town planning should be realistic and town planners have a big challenge while doing this[13]His statement makes clear he believes that cost is the main challenge for low-income housing and he asks city planners to find the way to generate funds through city planning and to ask how innovative planning can reduce the cost of the project.

7. Conclusions

- Housing is the most difficult basic need to fulfil worldwide, with millions of people living without habitable housing. This situation is severe in Asia and it is getting worse in urban areas such as Colombo, Sri Lanka. Therefore, it is an urgent requirement to develop a practical mechanism to address this issue. Throughout history successive Sri Lankan governments have chosen different strategies to overcome the problem of a shortage of habitable housing for the poor. High rise is one option selected by the Sri Lankan government to address the housing issues for low income people in Colombo City. However, high-rise low-income housing is a controversial option, and even in this case study of Colombo, Sri Lanka, there are examples of successful and unsuccessful high-rise low-income housing as well as low-rise low-income housing. However, there is a lack of literature that focuses on Sri Lanka and little research has been done in this field. Without extensive and in-depth evaluation of local and international experiences of high-rise low-income housing, the Sri Lankan government has made a policy decision to build 66,000 housing units in high-rise within the next six years[1]. At the time of writing, 12,000 housing units are being built and millions of Rupees are being spending on this project by the Urban Development Authority for the wellbeing of the city. The primary aim of this paper is to critically evaluate some international and local experiences in high rise low income housing and thus increase the knowledge base for when building houses for the 51 per cent of the Colombo population who are low-income people and need new, high density housing. The discussion in this paper provides support for the argument that “the Pruitt-Igoe myth”[2] holds lessons that remain relevant half a century later.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML