Adedeji Joseph Adeniran , Fadamiro Joseph Akinlabi

Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedeji Joseph Adeniran , Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Post occupancy evaluations (POE) have been discovered to be of high importance in building design decisions. The study explored POE to assess the users’ satisfaction with the office spaces of Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH) Senate Building, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. The aim was to measure the influence of workplace design quality on workers’ productivity to inform future design decisions. A questionnaire survey of 150 randomly sampled office workers in the building was carried out. The variables investigated on a 5-point scale were grouped into satisfaction and productivity parameters. Result of the data analysis shows correlation between self-reported workplace satisfaction and productivity. Recommendations were made on workplace design based on the result.

Keywords:

Office Workplace, Productivity, POE, Users’ Satisfaction, Workstation

1. Introduction

Post occupancy evaluation (POE) has been accepted as a research tool in assessing the efficiency of built forms. It has its root in the environment and behaviour studies from which workplace and productivity are direct derivatives. In particular, the main body of literature that attempts to link office environment and productivity largely addresses the physical environment[1]. The physical environment includes both internal and external qualities of the working area that dictates the worker’s comfort. This comfort is evaluated by office workers in terms of sense of security, building appearance, workstation comfort and overall visual comfort[2]. While the goal of every design - both building and its landscape - is to achieve maximum user’s comfort, the measure of its impact is in the realm environmental psychology[3]. However, built environment disciplines accept user’s assessment as a true measure of productivity[4-6].This study seeks to investigate the performance in use of the senate building of Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. The aim is to assess the design of the building and its landscape planning vis-à-vis the self-measured productivity of the users with the goal of identifying areas of possible improvement. The study becomes necessary in view of the complaints, both formal and informal, registered by users of the building consequent upon its form. The study will assist in determining the extent of the design flaws and appraise its qualities through a scientific approach. Importantly, product evaluation and quality control, in terms of product performance and customer satisfaction, is an accepted procedure in most industries. It would seem both natural and economical in the long run to carry out a thorough investigation of user-oriented “product” evaluation in the complex industry of design and construction[7]. It also promises to be of immense relevance in guiding future design decisions of such an important building in university campuses.

2. Conceptual Issues and Literature Review

2.1 Post Occupancy Evaluation

Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) has been defined as a platform for the systematic study of buildings once occupied so that lessons may be learned that will improve their current conditions and guide the design of future buildings[8]. The benefits from POE can be categorized into[7]:a. short-term benefits; obtaining users’ feedback on problems in buildings and the identification of solutions,b. medium-term benefits; feed-forward of the positive and negative lessons learned into the next building cycle,c. long-term benefits; aim at the creation of databases and the update, upgrade and generation of planning and design protocols and paradigms.POEs are classified as[6]:a. Indicative POEs which gives an indication of major strengths and weaknesses of a particular building’s performance;b. Investigative POEs which goes into more depth of the causes and effects of issues in building performance;c. Diagnostic POEs which correlates physical environmental measures with subjective occupant response measures.The scope of the present study falls within the Diagnostic POEs in which the occupants’ subjective views about the physical milieu of the building are measured.

2.2 The Values and Vices of Form

Students in a CAD/CAM class were presented with conflicting stories: on the one hand, they were told “machines are slaves – they’re dumb, they’re stupid. Yet, just a few days later – after considerable frustration with a lab project- students were told “you are also a slave to the computer”. Caught between these contradictory statements, these students began to question how much control they really had over the machine” [9, cited in 10].The excerpt above is much related to the interaction between man and his buildings once in place according to Le Corbusier’s metaphor, a building is a dwelling machine[11]. Our pleasures or pains in buildings that are direct confrontational experiences between the two are contingent upon the values and vices of the form of the building. While the values are the expressions of the ingenuity of the designer, the vices are the affliction brought upon the users called “designer fallacy”[12]. This fallacy could be “intentional” being inevitable consequent upon the designer’s “predetermined” choice of form which may not have been properly managed to serve such specific functions.In view of the above, the architect commissioned to design a project is often at a cross-road to decide the best form to be used especially when the building been designed is to serve as an overwhelming symbolic image. Louis Sullivan’s[13] popular motto of ‘form follows function’ if embraced by the designer, may salvage the situation. Elsewhere[11] it has been argued that utility value suffers if function is too much subordinate to form because “architecture is a regulated art” and “form is never totally free”. The implication is that form has some measure of autonomy and if this measure is properly engaged, a search for symbolic form of would be guided by principles such as “form follows aesthetics”, “form follows meaning”, “form follows profit”[14] since symbolism is a combination of perception and cognition[11]. The peculiar form of the Senate Building of Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), Ogbomoso, under study could be deduced to be “form follows aesthetics”.

3. The Senate Building, LAUTECH: A Brief Description

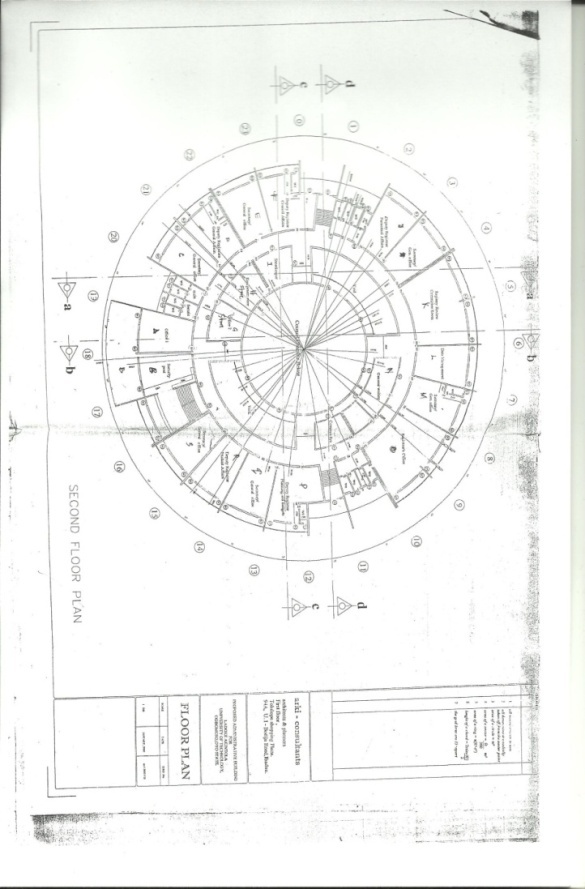

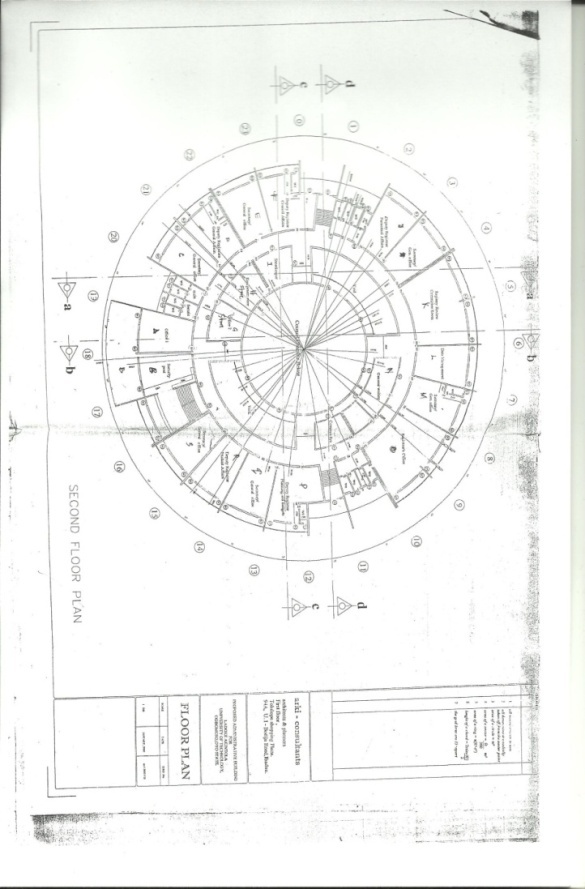

The building was designed and built in the year 2004 to accommodate the different central administrative functions of the university, established in 1990, earlier accommodated in different adapted structures within the campus. The building was designed as a circular form with an inner ring on 3 floors. The Ground Floor of the inner ring is an open exhibition hall, its 11/2 volume First Floor as Senate Chambers and its 11/2 volume Second Floor as Governing Council Chambers. The outer circular ring of 4 floors contain the offices. There is courtyard between the inner and outer rings (Plate 1-3). | Plate 1. Typical Floor Plan of Senate Building, LAUTECH, Ogbomoso, Nigeria (Source: Physical Planning Unit, LAUTECH, Nigeria, 2011) |

| Plate 2. Approach façade of LAUTECH Senate Building, Ogbomoso, Nigeria (Source: Authors, 2011) |

| Plate 3. Landscape features of LAUTECH Senate Building, Ogbomoso, Nigeria (Source: Authors, 2011) |

4. Methodology

The study was carried out through random survey sampling of 150 users of the building. The users were narrowed down to those staffs that have offices in the building being judged to spend considerable time in the building daily. A designed questionnaire for the study was administered upon them. The content of the questionnaire was based on the following measuring instruments for building performance evaluation:a. Searching for Data: A Method to Evaluate the Effects of Working in an Innovative Office[15]; andb. Post Occupancy Evaluation. University of Sao Paulo, Brazil[16].

5. Results and Discursion

5.1. Profile of Respondents

82 (54.7%) of the respondents were males while 68 (45.3%) were females. Their age distribution is as follow: less than 20years, 1 (0.7%); 21-30years, 38 (25.3%); 31-40years, 83 (55.3%); 41-50years, 25 (16.7%); above 50years, 2 (1.3%), not indicated, 1 (0.7%). Their educational qualifications are: primary school, 4 (2.7%); secondary school incomplete, 5 (3.3%); secondary school complete, 53 (35.3%); undergraduate, 30 (20.0%); graduate, 57 (38.0%). Furthermore, the respondents have the following work experiences: 1-5years, 90 (60.0%); >5-10years, 41 (27.3%); >10years, 17 (11.3%); not indicated, 2 (1.3%). The pattern and distribution of these profiles indicates the reliability on the evaluations of the sampled users as representative of the entire study population constituted by all users of the building who owns office accommodations within the building.

5.2. Respondents’ Work Programme

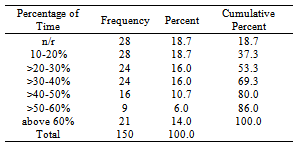

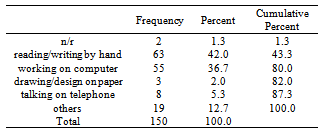

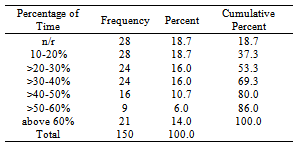

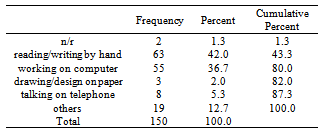

The periods of time spent at workstations as reported by the respondents are as shown in Table 1. From the table, various time-frames are reported between 10% and above 60% with the highest of 28 (18.7%) who reported that they were normally at their workstations for 10-20 % of the total daily working hours and the lowest of 9 (6.0%) who reported that they were normally at their workstations for >50-60% of the total daily working hours. The spread on the whole suggests the representativeness of the subjective opinions of the respondents on the evaluation of the building. Furthermore, the usual office tasks that the respondents normally carry out in their workstations are reported in Table 2. The table shows various activities ranging from reading/ writing by hand, 63 (42.0%); working on computer, 55 (36.7%); drawing/ design on paper, 3 (2.0%); others, 19 (12.7%); to talking on telephone, 8 (5.3%). The pattern implies that a wide range of office tasks are performed in the workstations that are sufficient to evaluate the efficiency of the building for office functions.Table 1. Percentage of Time Normally Spent at Work Station

|

| |

|

Table 2. Tasks Normally Carried out at Workstations

|

| |

|

5.3. POE of the Building as Reported by Respondents

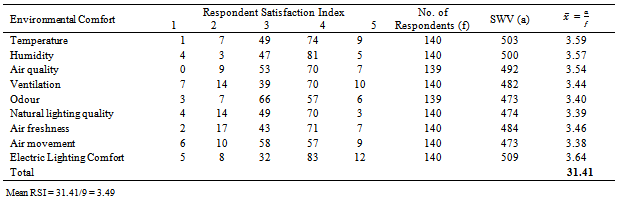

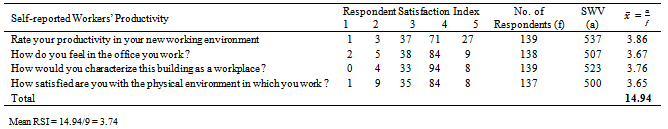

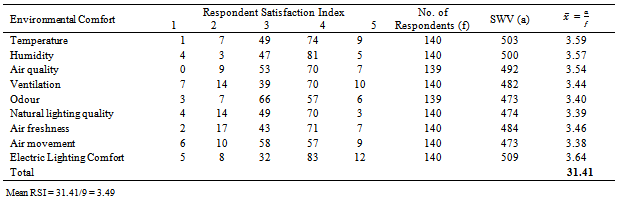

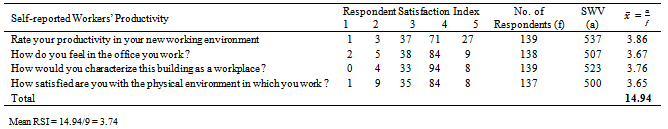

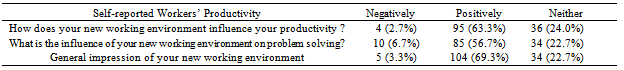

Tables 3 to 5 show the POE of the building with the following computation:f = No. of respondents SVW (a) = Sum of Weight ValueMean =  Average mean=

Average mean=  RSI = Respondent Satisfaction IndexThe RSI was prepared on a Likert Scale and represented as: Very unsatisfied = 1; Unsatisfied = 2; Neutral = 3; Satisfied = 4; Very satisfied = 5.The results of the POE are discoursed below in three sections of:a. Aspects of the Buildingb. Work Environment – Layout/Furniturec. Environmental Comfort

RSI = Respondent Satisfaction IndexThe RSI was prepared on a Likert Scale and represented as: Very unsatisfied = 1; Unsatisfied = 2; Neutral = 3; Satisfied = 4; Very satisfied = 5.The results of the POE are discoursed below in three sections of:a. Aspects of the Buildingb. Work Environment – Layout/Furniturec. Environmental Comfort

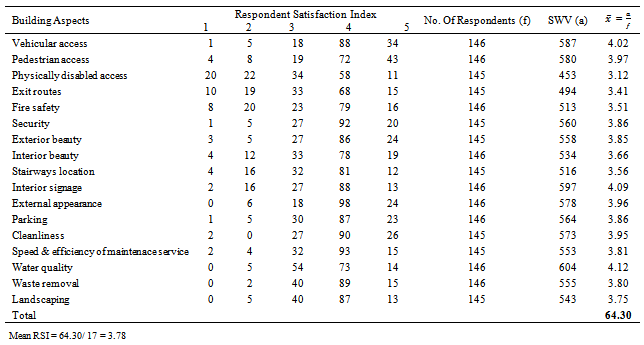

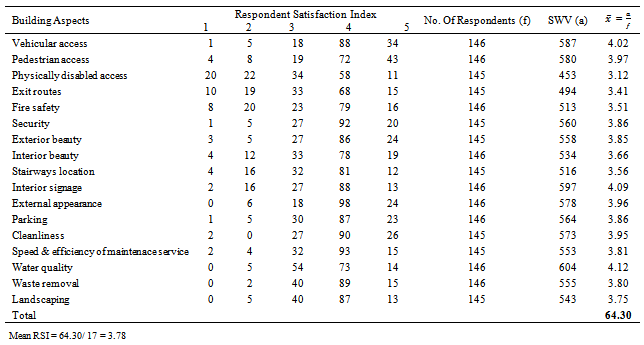

5.3.1 Aspects of the Building

Table 3 shows the Respondents Satisfaction Index (RSI) for various aspects of the building both indoor and landscaping. All the parameters evaluated were rated high enough to indicate their satisfactory performance. This excludes Access for physically disabled (3.12) and Exit routes (3.41) which tended towards the unsatisfactory side. On the interior parameters, Stairways location was evaluated as 3.56, Fire safety as 3.51, Security as 3.86, Interior signate as 4.09, Cleanliness as 3.95, Water quality as 4.12, Waste removal as 3.80, Speed and efficiency of maintenance service as 3.81 and Interior beauty as 3.66. On the exterior and landscaping parameters, Vehicular access was evaluated to be 4.02, Pedestrian access as 3.97, Exterior beauty, 3.85; Exterior beauty, 3.85; Parking, 3.86 and Landscaping, 3.75. The Mean RSI was 3.78 implying that the overall success of all aspects of the building, the value being very close to satisfied (4) but away from very satisfied (5). However, Physically disabled access and Exit routes needs to be improved. The means of improvement can be active since passive means are mostly explored at the design stage.Table 3. POE of Aspects of the Building

|

| |

|

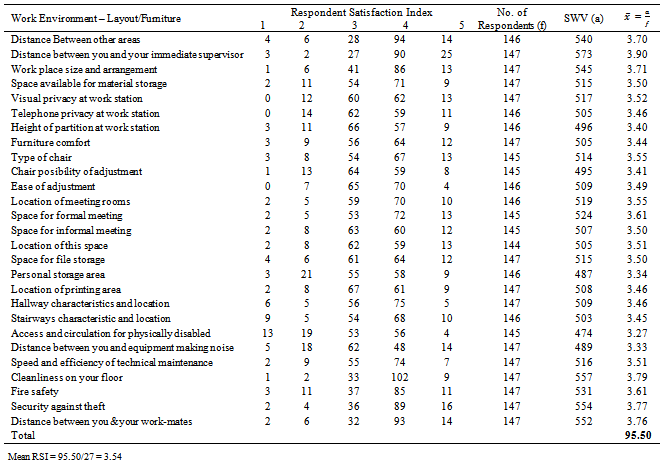

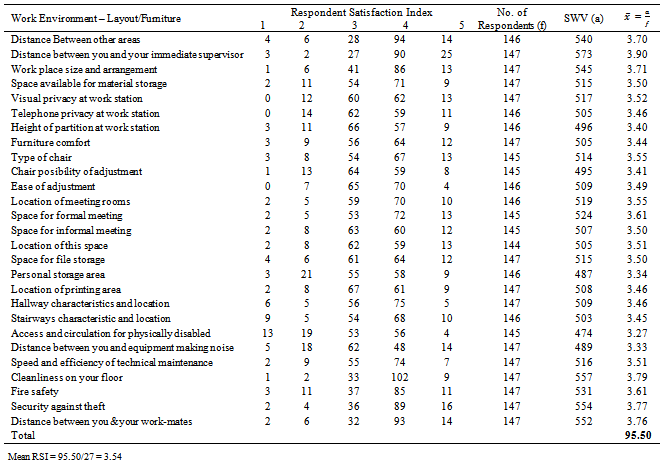

Table 4. Work Environment – Layout/Furniture

|

| |

|

5.3.2 Work Environment – Layout/Furniture

Table 4 below shows the result of the evaluation of work environment layout of the building. Because of the open plan concept of the office spaces and particularly the low attention that was given to individual work station, many of the factors were evaluated low. For instance, unsatisfactory height of partition was responsible for low privacy at workstations (3.46) while distance between workstations and equipments making noise was also evaluated low. Furthermore, there was less comfort in workstations furniture (3.44), attention was not paid to personal storage area (3.34), and there is no ease of furniture re-adjustment (3.41). On the whole, even though high values were obtained for Distance between areas (3.70) and to immediate supervisors (3.90), and distance between work mates (3.76), the overall Mean RSI (3.54) is low showing less desirability of open plan offices.

5.3.3 Environmental Comfort

The evaluation result for environmental comfort factors are shown in Table 5. The Mean RSI of 3.49 is low and reflects the low performance of the building in Air movement (3.38), Natural lighting quality (3.39), Ventilation (3.44) and Odour (3.40) while Electric lighting comfort (3.64) was relied upon. Consequently, there are dark areas within the building even in full sun-shining days, while Temperature (3.59), Humidity (3.57) and Air quality (3.54) possibly because of the plan form of the building’s design. Some offices, especially in the inner ring, are not supplied with natural climatic elements and therefore rely on the erratic power supply from the electricity mains.

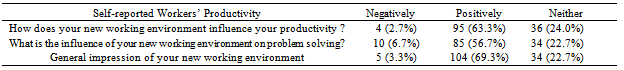

5.4. Self-reported Productivity of Workers

All the self-reported productivity factors of workers appears relatively high as shown in Table 6 just as this new work environment in the building was evaluated to have positive impact on the workers’ productivity in Table 7 compared to their former work stations scattered in various buildings within the campus. The overall relative success of the building is reflected in the Mean RSI (3.74) being close to satisfaction level (4). Productivity was evaluated as 3.86, Workplace satisfaction as 3.65, Emotional attachment to place as 3.67 and Place character as 3.76. This indicates that the physical environment only play a major role in productivity, it is not the only indicator of productive work environment. Despite some evaluated shortcomings of the building and its landscape, its successful aspects reflect in the higher productivity of workers who also evaluated the building as having positive impact on their productivity. Problems are solved more efficiently (56.7%), there was positive influence on productivity (63.3%) and there is higher place attachment (69.3%). Table 5. Environmental Comfort

|

| |

|

Table 6. Self-reported Workers’ Productivity

|

| |

|

Table 7. Building’s Impact on Self-reported Workers’ Productivity

|

| |

|

6. Conclusions

Architectural forms have both values and vices. The values are expressed as aesthetic and functional concepts while the vices are the aspects of buildings that do not satisfactorily perform in use. In the case of office buildings as workplaces, the office functions should be supported and enhanced by the architectural form used. The present study has shown that all aspects of a workplace have significant effect on the workers’ self-reported productivity. While an overall success may be achieved in workplace design on the surface, some aspects that are germane to crucial performance may fail. Because of the form adopted in the architectural design of the Senate Building under study, satisfactory levels of indoor environmental comfort was not achieved and appeared to have been sacrificed for the high aesthetic value achieved. While a satisfactory landscaping was achieved, it is not matched with the expected indoor air quality consequent upon the form. It therefore becomes necessary to achieve a suitable balance among form, functions and aesthetic performance during the design process of workplaces. The study confirmed the relationship between workplace and productivity and suggests the solution to achieving intelligent balance among design concerns.

References

| [1] | Haynes, B.P. (2007) An Evaluation of the Impact of Workplace Connectivity on Office Productivity. Proceedings of the Construction and Building Research Conference of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. Georgia Tech, Atlanta USA, 6-7 Sept. |

| [2] | Vischer, J.C. et al (2003) Mission Impossible on mission accomplie? Evaluation du Mobilier universel chez Desjardins Securite Financiere 2 vols. Technical report: Groupe de recherché sur les espaces de travail, Universite de Montreal. |

| [3] | Vischer, J.C and Fischer, G.N. (2005) User Evaluation of the Environment: A Diagnostic Approach P.U.F/le travail humain 2005/1 vol 68 pp 73-96. |

| [4] | Van der Voordt, T.J.M. (2004) Productivity and Employee Satisfaction in Flexible Workplaces. Journal of Cooperate Real Estate 6 (2); 133-148 Henry Stewart Publications. |

| [5] | Hassanain, M.A. (2010) Analysis of Factors Influencing Office Workplace Planning and Design in Corporate Facilities. Journal of Building Appraisal (2010) 6: 183-197. |

| [6] | Preiser, W.F.E and Schramm, U. (2002) Intelligent Office Building Performance Evaluation. Facilities, Vol. 20,7/8, 299-287. |

| [7] | Preiser, W.F.E. and Vischer, J.C. (2005) The Evolution of Building Performance Evaluation: An introduction. In Assessing Building Performance. Preiser, W. F.E. and Vischer, J.C. (eds.). Burlington: Elsevier Butterworth – Heinemann |

| [8] | Meir, I. A., Garb Y., Jiao D. and Cicelsky A. (2009) Post-Occupancy Evaluation: An Inevitable Step Toward Sustainability. Advances in Building Energy Research Vol. 3 pp: 189-220. |

| [9] | Downey, G. (1998) The Machine in Me: An Anthropologist Sits Among Computer Engineers. Routledge, NJ. |

| [10] | Feng, P. and Feenberg, A. (2008) Thinking About Design, Critical Theory of Technology and the Design Process. In Vermaas, P.E., Kroes, P., Light, A., and Moore, S.A. (eds.) Philosophy and Design: From Engineering to Architecture. Springer Science + Business Media B.V. pp. 105-108. |

| [11] | Voordt, T.J.M. and Wegen, H.B.R. (2005) Architecture in Use: An Introduction to the Programming, Design and Evaluation of Buildings. Amsterdam: Architectural Press pp. 1-70 |

| [12] | Ihde, D. (2008) The Designer Fallacy and Technological Imagination. In Vermaas, P.E., Kroes, P., Light, A., and Moore, S.A. (eds.) Philosophy and Design: From Engineering to Architecture. Springer Science + Business Media B.V. pp. 50 |

| [13] | Sullivan, L. (1924) The Autobiography of an Idea. New York. |

| [14] | Rogers, R. (1991) Architecture: A Modern View. London: Thames and Hudson |

| [15] | Vos, P.G.J.C. and Dewulf, G.P.R.M. (1999) Searching for Data: A Method to Evaluate the Effects of Working in an Innovative Office. Delft University Press |

| [16] | Ornstein, S.W., de Andrade, C.M. and Leite, B.C.C. (1998) Post Occupancy Evaluation. Research Center for Architecture and Urban Design Technology, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

Average mean=

Average mean=  RSI = Respondent Satisfaction IndexThe RSI was prepared on a Likert Scale and represented as: Very unsatisfied = 1; Unsatisfied = 2; Neutral = 3; Satisfied = 4; Very satisfied = 5.The results of the POE are discoursed below in three sections of:a. Aspects of the Buildingb. Work Environment – Layout/Furniturec. Environmental Comfort

RSI = Respondent Satisfaction IndexThe RSI was prepared on a Likert Scale and represented as: Very unsatisfied = 1; Unsatisfied = 2; Neutral = 3; Satisfied = 4; Very satisfied = 5.The results of the POE are discoursed below in three sections of:a. Aspects of the Buildingb. Work Environment – Layout/Furniturec. Environmental Comfort Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML