-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Advances in Philosophy

2021; 3(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ap.20210301.01

Received: Dec. 6, 2020; Accepted: Jan. 5, 2021; Published: Jan. 15, 2021

America’s Reaction to the Global Financial Crisis

Elsie H. Dunnam

IICSE University, Wilmington, USA

Correspondence to: Elsie H. Dunnam , IICSE University, Wilmington, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article brings a discussion about how the American police coped with the events involving the global financial crisis, which generated reduction of even 50% in their figures. The readership that would most benefit from the findings would be the own police, and the government. The discussion goes through insightful study of the sources, where at least three fronts of investment have been identified: working with the community, technology, and managerial change. Inside of working with the community, community policing of a certain type, and partnership policing clearly showed very positive, and quantifiable, plus quantified results in the consulted, and mentioned sources. Inside of technology, it was the Body-Worn Video, and the Domain Awareness System that played the same role, of reassuring us on the solidity of the results of the selected sources. The conclusion is that, despite the much that has changed in management, much more can change to produce an even greater amount of positivity, and certain strategies, such as foot patrols with Broken Windows Policy in hotspots, work better than others. The inferential work is based on Mathematical Logic, and the selected sources are studied through the lens of the top levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Keywords: Crisis, Management, Police, Community

Cite this paper: Elsie H. Dunnam , America’s Reaction to the Global Financial Crisis, International Journal of Advances in Philosophy, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ap.20210301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Some believe the crisis started in 2007 (Choi 2013, p. 65). Some pinned 2008 as the actual crisis (Zwiers, Bolt, & Kempen 2016, p. 664) time. The Global Financial Crisis seems to be a title that became a unique mark at a very determined point in time. Pautz (2017) says this time should be 2007, and 2008 (p. 191), but he says his article focuses on the time period 2007-2015; the start of the crisis, and the end of “Britain’s coalition government of Conservatives, and Liberal Democrats under David Cameron as Prime Minister which led Britain into an ‘age of austerity’ (p. 192).”According to Hurley (2020, Major Assignment), the United Kingdom, Europe, Canada, America, and the Russian Federation dismissed, “disengaged, or retrenched” their police officers to a rate of about two million from 2010 to 2015 for believing cutting down on their figures made their nations be on top of their debts, and therefore more able to fight the “global financial crisis”. This is the worst crisis since the 30s (Levy 2010, p. 234), and managers decided to invest in regulation, and auditing (Levy 2010, p. 238). Auditing focuses on councils, and their partners (Levy 2010, p. 238). As a result, the number of authorities was sometimes dramatically reduced: 44 to 9 local authorities in England in 2009 (Levy 2010, p. 238). In Scotland, one organisation, Police Scotland, was created in 2013 to substitute eight police constabularies, and their support agencies (Brown 2017, p. 7). With fewer authorities, and top managers acting as a group (chief executives) (Levy 2010, p. 238), solutions would take shorter to be put into practice, and would have to be more effective. More effective solutions, and shorter time between theory, and practice is good because those nations still had to fight crime, and we then wonder about how America managed to do the same tasks with half of the manpower (Hurley 2020, Major Assignment): what was put there to address this issue?

2. Methods

- The methods employed in this paper were critical literature review, and Bloom’s synthesis, and analysis (Pinheiro 2015, p. 136). Inferential work was based on mathematical logic (Pinheiro 2017, pp. 10-20). Some of the sources use data from surveys, and experimentation.

3. Development

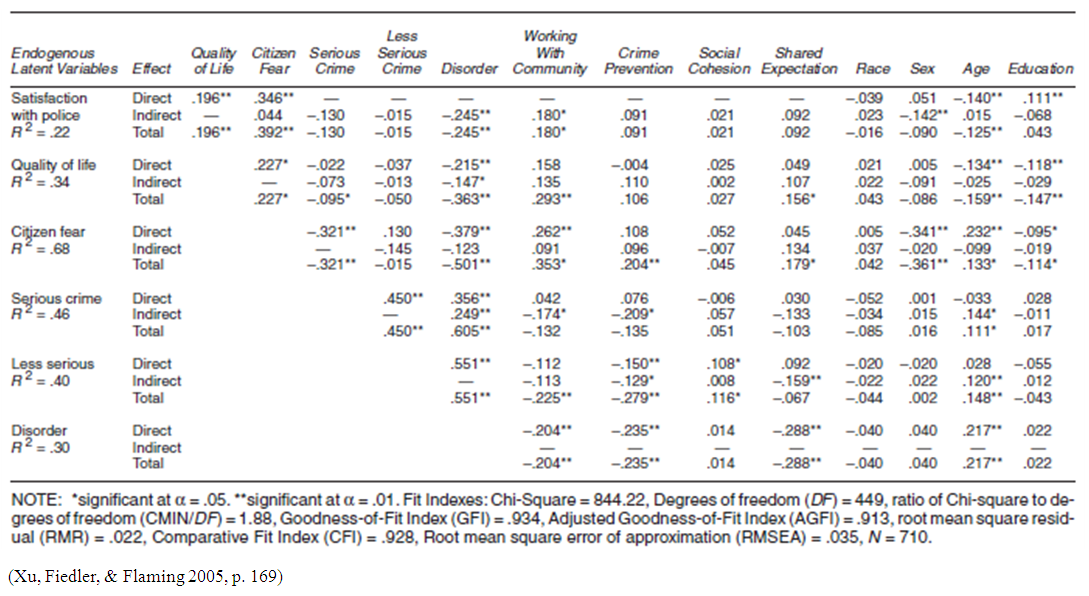

- Among remedies administered by America were investments in technology, working with the community (Willis 2005, p. 1315), and management-style changes (Sarre & Prenzler 2018, pp. 11-12).Inside of working with the community, community policing, or community-oriented policing (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2020, para. 2), was a solution [(Willis 2005, p. 1315), (Xu, Fiedler, & Flaming 2005, pp. 173-176)]: police then stress foot patrol, and services to the community (Sarre & Prenzler 2018). Community-oriented policing (COP – (Makin & Marenin 2017, p. 421) usually comes as a response when the relationship between police, and the people is not going well (Cordner 2014, p. 2), and COP, in the United States, appears together with dramatic reduction in crime rates (Cordner 2014, p. 2).

|

4. Conclusions & Recommendations

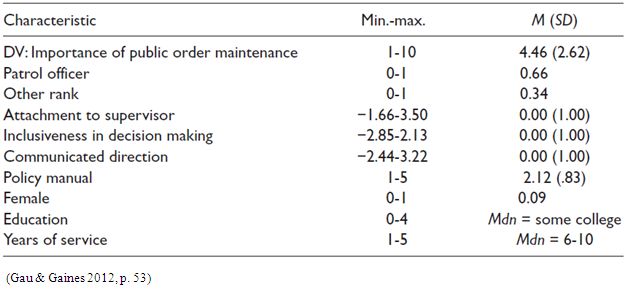

- The American police invested at least in changes in management, technology, partnership policing, and COP to compensate the reduction in budget, and officers during the period 2010-2015.Technology improves results to the side of victims, and police work: DAS, which is both partnership, and technology increase, saved the government tens of millions of dollars per year. In what regards BWV, “a UK Home Office Study reported a 22% reduction in the time devoted to paperwork, and case preparation due to evidence collected from BWV” (Bowling & Iyer 2019, p. 11). BWV brought a reduction of even 93% in complaints about officers (Bowling & Iyer 2019, p. 14). Even though the rate of complaints increased in some locations instead of decreasing, it seems that it has to do with size of the police, and nature of the complaint: small groups would have the rate reduced, and complaints about the use of force would definitely present a lower rate (Bowling & Iyer 2019, p. 14). This all points at advice on managerial directions. Management can be improved through simple decisions, and procedures, such as improving hiring, and supervision to improve influencing, then improving the work routine of supervisors. The style of the policing is also important: Hotspots that got more foot patrols got more reduction in crime. To maximise results, the best investment is concentrating on hotspots of hotspots, hotspots, and their respective neighbourhoods, adopting the Broken Windows Policy, increasing the number of foot patrols, and assigning groups of officers in a fixed manner to those neighbourhoods. Research should always separate well one style of policing from another, and COP, in particular, can only be properly studied if types are separated in an exact manner.

5. Main Research Findings

- The Global Financial Crisis started in August of 2007, and finished in 2008, but its causes, and implications go from at least 2007 to 2015. Police reactions to the crisis are worth studying because we can learn from them, and optimise efforts more logically during similar future events. Broken Windows can easily be treated as a strategy in top policing. That makes the population be more together with police if it is applied in hot spots, but the reduction of the crime rate is also non-negligible. Body-Worn Video should also be treated as a strategy in top policing. It produces relief to the domestic violence victim’s suffering, and also helps them have a better result at the courts, therefore increases justice levels. Police is more protected in their work routine. Partnerships with police also lead to impressive results, and if the state is functionally absent, the matching is better, and the partnership is truer.

6. Future Directions

- These research results could again be split, this time with the focus of this paper: modelling things properly, organising data better, and creating indices to measure the efficacy of each strategy, but also to treat them in a more similar way. Whether the focus is on human rights, and suffering, or chances of individual victims, or expenditure, it is necessary to set up the same paradigms for the main strategies for police. After the paradigms are sorted, it is still necessary to establish a scale of importance for the strategy within the realm of the government, then of the population, then of the own police, and so on.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank the editors of this journal for their remarks, and suggestions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML