-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Applied Mathematics

p-ISSN: 2163-1409 e-ISSN: 2163-1425

2025; 14(1): 1-11

doi:10.5923/j.am.20251401.01

Received: Oct. 9, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 2, 2025; Published: Dec. 3, 2025

An Investigation of a Sharp-Interface Lattice Boltzmann Method for High Density Ratio Multicomponent Flows

Paris Smith1, Yong Yang2, Caixia Chen1

1Department of Mathematics and Statistical Sciences, Jackson State University, Jackson, USA

2Department of Mathematics, Western Texas A&M University, Canyon, USA

Correspondence to: Caixia Chen, Department of Mathematics and Statistical Sciences, Jackson State University, Jackson, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Accurate simulation of multiphase flows with large density ratios, such as air-water interactions, is a longstanding challenge in computational fluid dynamics. In this work, we investigate a sharp-interface lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) enhanced by a modified surface tension algorithm inspired by the Shan-Chen model. This method enables the simulation of droplet dynamics with improved stability and fidelity, even at density ratios exceeding 1000:1. We validate the method by benchmarking against traditional high-resolution techniques, demonstrating strong agreement in key dynamic behaviors. To further enhance the analysis, we incorporate machine learning algorithms to classify droplet collision outcomes—coalescence, separation, and secondary droplets—based on LBM simulation data. The resulting model aligns well with physical intuition and exhibits robust predictive performance, bridging data-driven insights with physics-based modeling.

Keywords: LBM, High Density Ratio, Droplets

Cite this paper: Paris Smith, Yong Yang, Caixia Chen, An Investigation of a Sharp-Interface Lattice Boltzmann Method for High Density Ratio Multicomponent Flows, Applied Mathematics, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.5923/j.am.20251401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Multiphase fluid dynamics governs a wide range of natural and industrial processes, including inkjet printing, emulsification, spray cooling, and biological systems such as raindrop interactions and magma fragmentation. Accurate modeling of these complex flows requires numerical schemes capable of capturing interfacial Deformation, topological transitions, and phase interactions across multiple scales. The foundation for modern high-fidelity numerical methods was established by Patera [1], who introduced the spectral element method combining the flexibility of finite elements with the spectral accuracy of global polynomial expansions. This framework was expanded by Cockburn, Lin, and Shu [2], who developed the Runge–Kutta discontinuous Galerkin (DG) formulation for conservation laws, later refined for convection–diffusion systems by Cockburn and Shu [8]. High-order ENO and WENO shock-capturing schemes proposed by Shu and Osher [3,4] further improved the treatment of discontinuities while maintaining numerical stability and accuracy. Bassi and Rebay [7] extended these methods for compressible Navier–Stokes equations, enabling large-scale, high-order simulations.The evolution of high-order numerical formulations continued with compact and Padé-type ENO schemes by Ma and Fu [10] and Wang and Huang [12], improving dispersion control and accuracy in wave-dominated flows. Subsequently, Liu, Vinokur, and Wang [17,18] formulated the spectral volume (SV) and spectral difference (SD) methods for unstructured grids, extended to multidomain three-dimensional Navier–Stokes solvers by Sun, Wang, and Liu [19]. These methods have collectively advanced the resolution and stability of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) solvers for multiphase flow problems.Parallel to these developments, the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) emerged as a mesoscopic alternative capable of simulating multiphase and multicomponent systems. The seminal work of Shan and Chen [5] introduced interparticle interaction forces to model phase separation and surface tension effects, while He and Luo [6] provided a rigorous theoretical framework linking the Boltzmann and lattice Boltzmann equations. However, subsequent models—such as Xing et al. [16], who proposed a perturbation-based single-phase surface tension model—imposed viscosity constraints that limited numerical stability. These challenges were later mitigated by Lee and Lin [15], who developed a stable discretization for incompressible two-phase flows at high density ratios.Experimental studies by Gueyffier and Zaleski [13] and Cossali et al. [14] provided key insights into droplet splashing and coalescence phenomena, emphasizing the importance of Weber and Reynolds number interactions in determining collision outcomes. Complementary theoretical and numerical studies by Wang and Chen [9] and Succi [11] further reinforced the role of mesoscopic modeling in predicting complex fluid behaviors. By integrating these foundational advances, the present study leverages a sharp-interface LBM framework capable of resolving droplet deformation, Coalescence, and secondary breakup across a broad range of Reynolds and Weber numbers.Finally, the incorporation of machine learning frameworks has transformed post-simulation analysis by enabling automated classification and prediction of droplet behaviors. Recent studies by Brunton and Kutz [20] and Yu and Chang [22] demonstrated the efficacy of physics-informed and data-driven models for understanding nonlinear flow regimes, while Bureš and Sato [21] applied sharp-interface phase-change models for evaporation and condensation. Building upon these advances, the present work integrates high-order numerical techniques with machine learning models—such as Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost—to predict and classify droplet collision outcomes, bridging physical modeling with data-driven insight.

2. Numerical Methods

- In this section, we describe the lattice Boltzmann formulation used to simulate sharp- interface multiphase flows. Our approach is based on the standard LBGK (Lattice Bhatnagar–Gross–Krook) model and incorporates a modified surface tension algorithm inspired by the Shan–Chen multiphase interaction model. This numerical framework enables simulations of high-density ratio systems, such as air–water flows, by improving interface stability and eliminating constraints on the relaxation parameter.

2.1. Lattice BGK Formulation

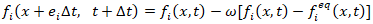

- The evolution of the particle distribution function

in the LBGK scheme is governed by the equation:

in the LBGK scheme is governed by the equation: where:•

where:•  is the particle distribution function in the i-th direction,•

is the particle distribution function in the i-th direction,•  are discrete lattice velocities,•

are discrete lattice velocities,•  is the relaxation rate,•

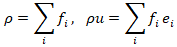

is the relaxation rate,•  is the equilibrium distribution function.The macroscopic density and velocity are recovered through the moments:

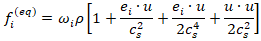

is the equilibrium distribution function.The macroscopic density and velocity are recovered through the moments: The equilibrium distribution function used is:

The equilibrium distribution function used is: where

where  are direction weights and

are direction weights and  is the lattice sound speed.

is the lattice sound speed.2.2. Sharp-Interface Free Surface Assumption

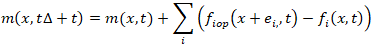

- Our model assumes that liquid and gas phases do not overlap; the interface is sharp and physically distinct. The gas density is treated as negligible, and its dynamic contribution is excluded from the simulation. The simulation tracks cell status—liquid, gas, or interface—by evolving the cell mass:

Interface dynamics are managed by reclassifying cells based on mass thresholds. These updates enable dynamic interface reconstruction.

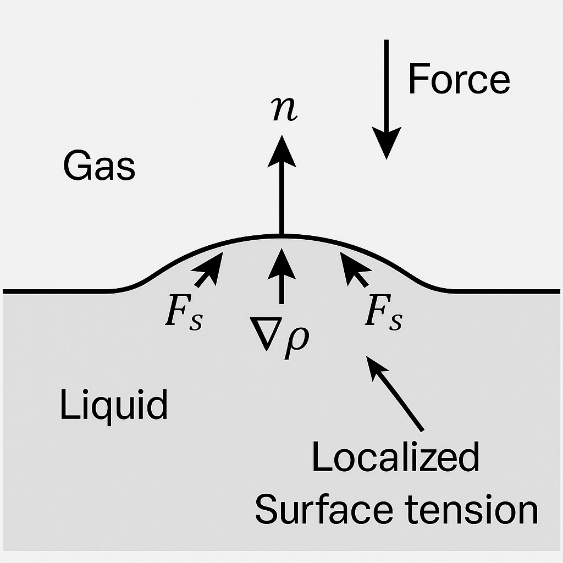

Interface dynamics are managed by reclassifying cells based on mass thresholds. These updates enable dynamic interface reconstruction.2.3. Modified Surface Tension Force

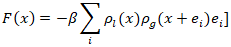

- To enhance accuracy and stability, we incorporate a surface tension model as an external interfacial force based on Shan and Chen’s interaction framework. The original method by Xing et al. [16] introduced a perturbation function to the distribution functions but imposed a strict limit on viscosity and increased numerical complexity [16]. In contrast, our method applies a repulsive force between fluid and gas cells:

where:•

where:•  is the liquid density,•

is the liquid density,•  is a constant (representative) gas density,•

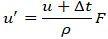

is a constant (representative) gas density,•  is a tunable parameter proportional to surface tension.This force is applied only at interface cells where fluid and gas are adjacent. The post-collision velocity is modified as:

is a tunable parameter proportional to surface tension.This force is applied only at interface cells where fluid and gas are adjacent. The post-collision velocity is modified as: This formulation allows for greater numerical flexibility by eliminating the viscosity limitation and enhancing stability at high Reynolds and Weber numbers.

This formulation allows for greater numerical flexibility by eliminating the viscosity limitation and enhancing stability at high Reynolds and Weber numbers.2.4. Model Advantages

- Compared to traditional methods, the proposed approach offers several advantages. In particular, the relaxation time τ is not restricted to values close to unity; it can be set to values greater than one, enabling stable simulations of high-viscosity fluids that are often challenging for conventional LBM formulations. Second, interface tracking is significantly more stable, owing to the implementation of a repulsive force formulation that enhances phase separation and reduces numerical diffusion. Lastly, the model robustly handles density ratios as high as 1000:1, making it well-suited for realistic air–water interactions commonly observed in multiphase flow scenarios. This improved numerical scheme provides a robust foundation for simulating droplet dynamics and collision phenomena, which are further explored in the validation and results sections.

2.5. Governing Equations and Dimensionless Parameters

- Accurate simulation of multiphase systems depends on non-dimensional quantities that reflect the interplay between key forces. Three main parameters are used throughout this work:• The Reynolds number quantifies the ratio of inertial to viscous forces:

where

where  is the fluid density,

is the fluid density,  is the relative velocity,

is the relative velocity,  is the droplet diameter, and

is the droplet diameter, and  is the dynamic viscosity.• The Weber number represents the ratio of inertial forces to surface tension forces:

is the dynamic viscosity.• The Weber number represents the ratio of inertial forces to surface tension forces: where

where  is the surface tension.• The Ohnesorge number represents the ratio of internal viscosity dissipation to the surface tension energy:

is the surface tension.• The Ohnesorge number represents the ratio of internal viscosity dissipation to the surface tension energy: where

where  is the surface tension.• The impact parameter indicates the offset of colliding droplet centers:

is the surface tension.• The impact parameter indicates the offset of colliding droplet centers: where

where  is the lateral distance between droplet centers.

is the lateral distance between droplet centers.3. Numerical Procedure and Results

- This chapter presents the results of numerical simulations performed using the sharp-interface Lattice Boltzmann Method, followed by validation against VOF results. To complement these findings, a machine learning-based classification of droplet collision outcomes is also introduced, leveraging data generated from the simulations.In particular, we investigate and classify the dynamic behaviors that emerge during binary droplet collisions. These behaviors—stretching, Coalescence, Separation, and secondary droplet formation—represent the fundamental modes of interaction observed under varying flow conditions. Each regime is defined by the relative contributions of inertial, viscous, and surface tension forces, encapsulated in dimensionless parameters such as the Reynolds (Re) and Weber (We) numbers.Stretching occurs when droplets deform into elongated shapes upon collision but remain connected, often forming slender liquid threads with larger bulbous ends. This regime is particularly sensitive to surface tension, which resists the breakup of the droplets and maintains their overall integrity. By contrast, Coalescence is characterized by the seamless merging of two droplets into a single, larger droplet, driven by surface tension’s tendency to minimize surface energy. In this regime, the fluid bridge between the droplets expands rapidly, creating a smooth, unified interface.Separation arises when inertial forces dominate over surface tension, causing the droplets to rebound or split into three separate entities after impact. Finally, secondary droplet formation occurs when the collision energy is sufficiently high to fragment the droplets into four or more smaller droplets. This complex regime often involves both stretching and rupture dynamics, and it plays a critical role in understanding atomization processes, spray dynamics, and aerosol generation.The results presented in this chapter provide a detailed examination of these four behaviors, revealing how variations in Re and We dictate the transition between regimes. The following sections guide the reader through high-fidelity simulations and visualizations of these outcomes, setting the stage for a deeper exploration of the underlying physics and the machine learning-based classification framework introduced in Section 3.3.

3.1. Numerical Results

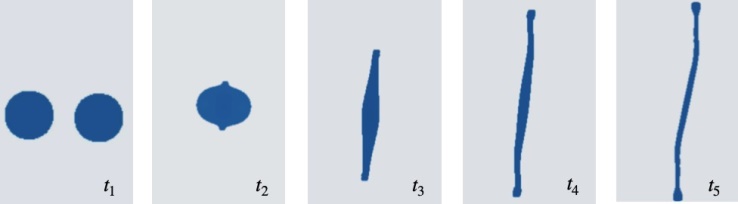

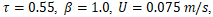

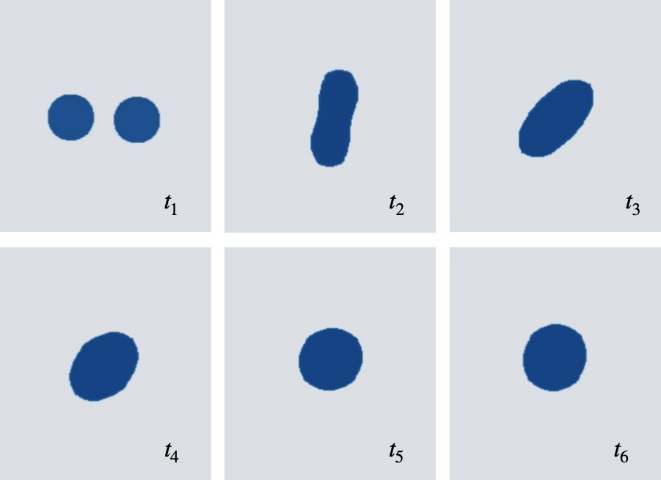

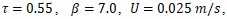

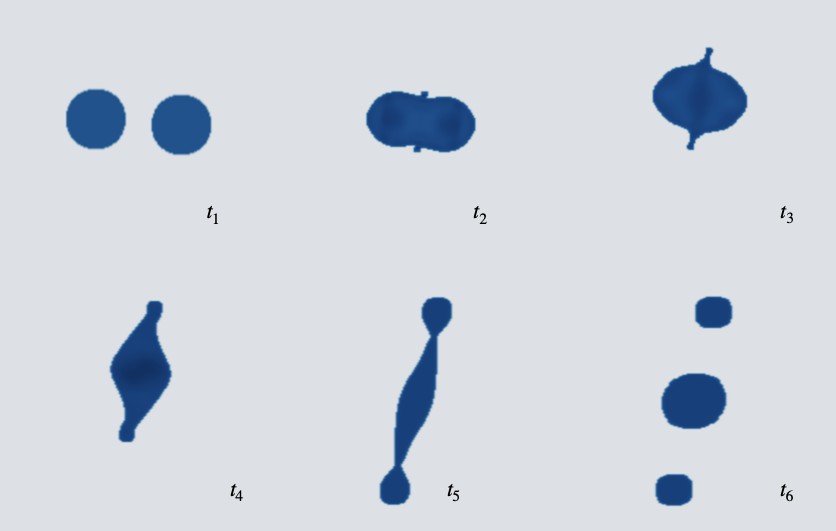

- As illustrated in Figure 2, the fluid droplets exhibit significant viscosity and undergo noticeable stretching without fragmentation. The LBM simulation demonstrates a high degree of accuracy and numerical stability, with no visible discrepancies. These results highlight the robustness of the proposed algorithm in handling highly viscous flows, even with a relaxation time of

.

. and

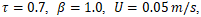

and  At this configuration, the flow exhibits a Reynolds number of approximately

At this configuration, the flow exhibits a Reynolds number of approximately  and a Weber number of

and a Weber number of  placing the system near the threshold where inertial forces begin to overcome surface tension. As a result, the primary droplets deform upon impact and eject smaller satellite droplets, while the main fluid bodies remain partially intact. This regime demonstrates the onset of droplet fragmentation, driven by a balance between viscous resistance and capillary instability.

placing the system near the threshold where inertial forces begin to overcome surface tension. As a result, the primary droplets deform upon impact and eject smaller satellite droplets, while the main fluid bodies remain partially intact. This regime demonstrates the onset of droplet fragmentation, driven by a balance between viscous resistance and capillary instability. and a reduced Reynolds number

and a reduced Reynolds number  . This behavior is attributed to the combination of high surface tension

. This behavior is attributed to the combination of high surface tension  and a low impact velocity

and a low impact velocity  which together suppress inertial effects and promote interfacial merging. Under these conditions, the capillary forces dominate, facilitating the Coalescence of the droplets without significant Deformation or breakup.

which together suppress inertial effects and promote interfacial merging. Under these conditions, the capillary forces dominate, facilitating the Coalescence of the droplets without significant Deformation or breakup.3.2. Validation of the Numerical Model

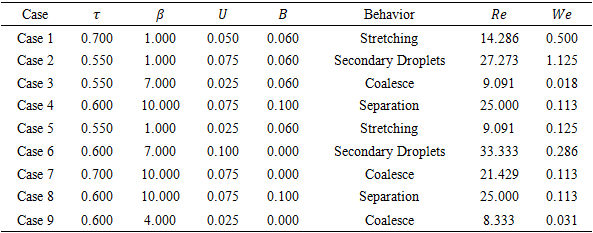

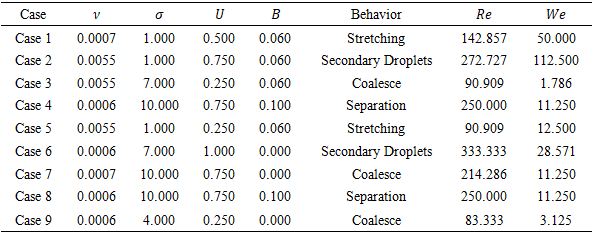

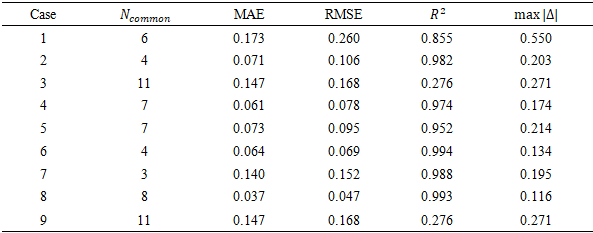

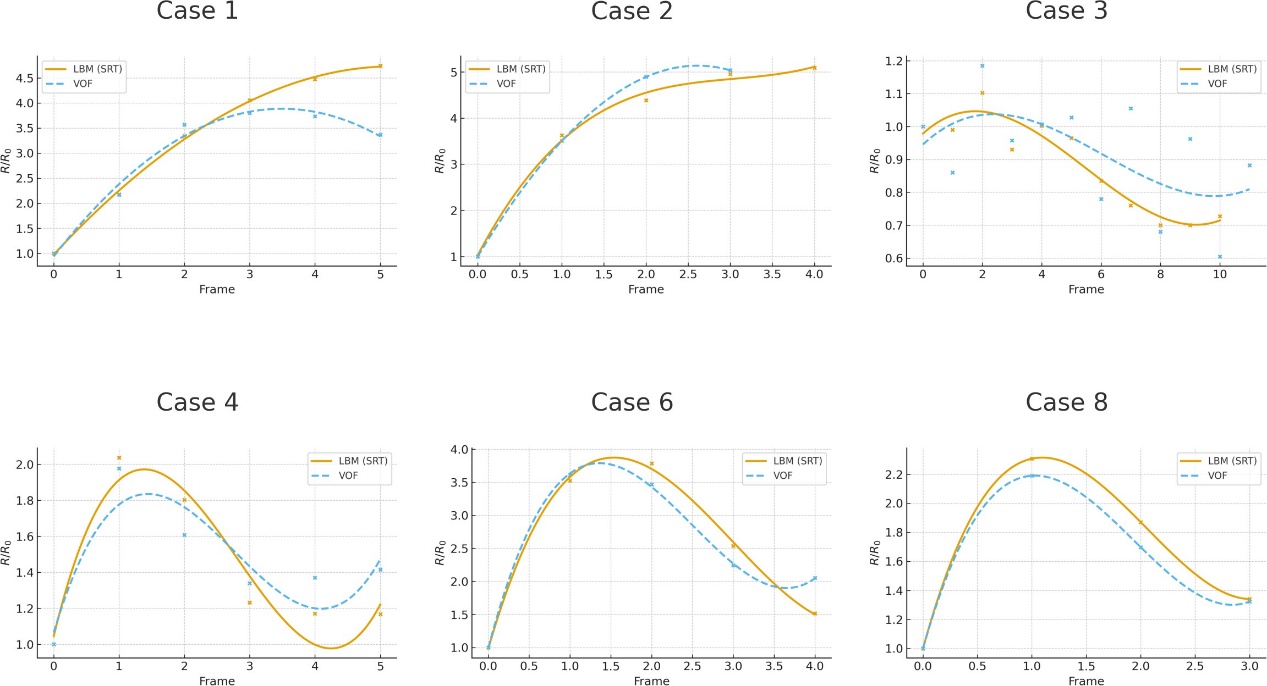

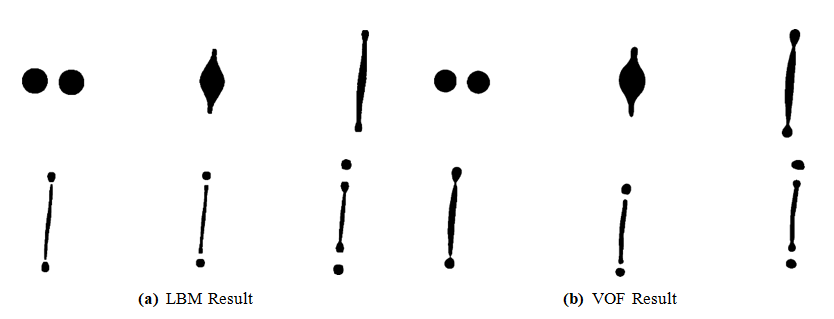

- To validate the numerical approach, we first examine the mesh configuration and the ability of the model to capture the droplet interface. A refined mesh of 201 x 401 cells is used to ensure accurate resolution of the interface dynamics. We compare each of the frames of the images and record its behavior.To verify physical realism, we compare LBM result frames with VOF results, as shown in Figure 6. Visual similarity is seen across behaviors in Table 1 such as Stretching and Separation.

|

using frames common to both solvers (Table 4).

using frames common to both solvers (Table 4).

|

|

|

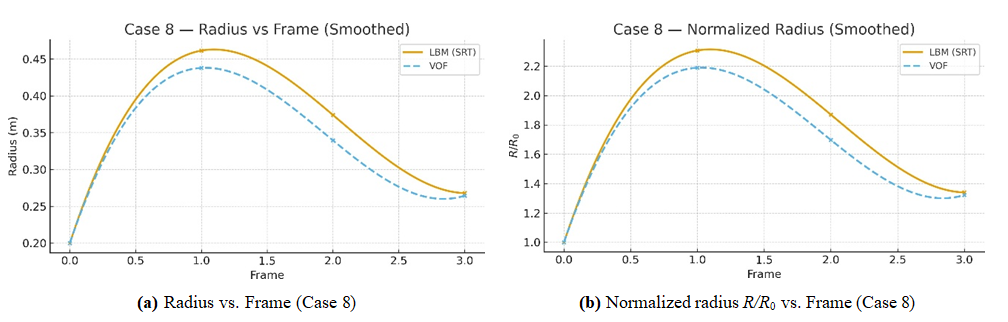

of 0.993. Figure 7 illustrates this agreement through side-by-side plots of the dimensional radius (left) and normalized radius

of 0.993. Figure 7 illustrates this agreement through side-by-side plots of the dimensional radius (left) and normalized radius  Both solvers capture the same time history, including the timing of the peak and subsequent relaxation, with only a modest amplitude difference at maximum Deformation. Normalization by

Both solvers capture the same time history, including the timing of the peak and subsequent relaxation, with only a modest amplitude difference at maximum Deformation. Normalization by  further highlights the near-identical shape of the droplet evolution.

further highlights the near-identical shape of the droplet evolution. overlays for all nine cases. Most cases exhibit close alignment in the timing of extrema and relaxation rates, with occasional deviations (up to 10%) at frames of maximum Deformation. Cases with fewer overlapping frames (Table 4) appear sparser but adhere to the same trends. These findings indicate that LBM (SRT) and VOF consistently resolve the dominant droplet dynamics across all configurations, with residual differences likely attributable to model-form choices rather than significant numerical errors.

overlays for all nine cases. Most cases exhibit close alignment in the timing of extrema and relaxation rates, with occasional deviations (up to 10%) at frames of maximum Deformation. Cases with fewer overlapping frames (Table 4) appear sparser but adhere to the same trends. These findings indicate that LBM (SRT) and VOF consistently resolve the dominant droplet dynamics across all configurations, with residual differences likely attributable to model-form choices rather than significant numerical errors. | Figure 8. Normalized radius R/R0 vs. Frame for best cases |

3.3. Machine Learning Classification of Droplet Outcomes

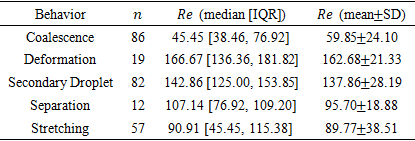

- The purpose of applying machine learning in this context is to augment traditional fluid dynamics analysis by enabling fast, automated classification of droplet collision outcomes. While conventional simulation methods such as LBM provide detailed physical insight, interpreting the resulting behaviors across large datasets is time-consuming and subjective. By training classifiers on 254 simulations, we aim to identify key patterns and nonlinear relationships between physical parameters, as shown in Tables 5 and 6

and observed droplet behaviors. This data-driven approach not only accelerates post-processing but also enhances predictive capabilities, offering a scalable solution for analyzing vast parameter spaces and improving the interpretability of multiphase flow phenomena.

and observed droplet behaviors. This data-driven approach not only accelerates post-processing but also enhances predictive capabilities, offering a scalable solution for analyzing vast parameter spaces and improving the interpretability of multiphase flow phenomena.

|

|

across all observed droplet behaviors, providing a clear physical interpretation of how inertial effects influence collision outcomes. The results reveal that Coalescence occurs primarily within the lowest

across all observed droplet behaviors, providing a clear physical interpretation of how inertial effects influence collision outcomes. The results reveal that Coalescence occurs primarily within the lowest  range (median = 45.45 [IQR 38.46–76.92]), indicating that viscous and surface tension forces dominate under these conditions, promoting the smooth merging of droplets. In contrast, Deformation exhibits the highest Reynolds numbers (mean = 162.68 ± 21.33), where inertial forces are sufficiently strong to overcome interfacial tension, resulting in significant droplet elongation or breakup. The secondary droplet regime also occurs at high Re values (mean = 137.86 ± 28.19), suggesting that instability at impact leads to satellite formation when inertia approaches or exceeds surface tension resistance.Intermediate behaviors such as Separation (mean = 95.70 ± 18.88) and stretching (mean = 89.77 ± 38.51) occupy transitional Reynolds number ranges, where neither viscous nor inertial forces are entirely dominant. These regions mark the thresholds between stable Coalescence and unstable fragmentation, emphasizing the sensitive dependence of collision outcomes on inertia. The broad interquartile range observed in stretching behavior further indicates variability in droplet deformation patterns, often linked to minor variations in impact velocity or alignment. Overall, the Reynolds number statistics in Table 5 provide quantitative evidence that increasing inertia systematically drives the progression from Coalescence to deformation and secondary droplet formation, aligning with both experimental findings and the trends captured by the LBM simulations.Table 6 presents the Weber number

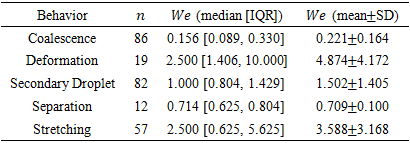

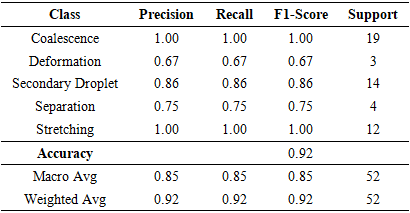

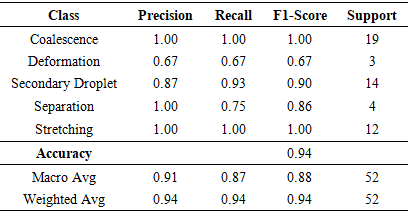

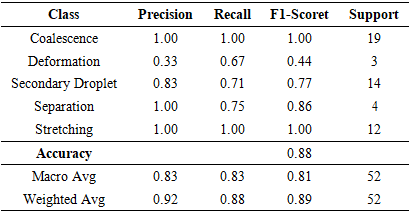

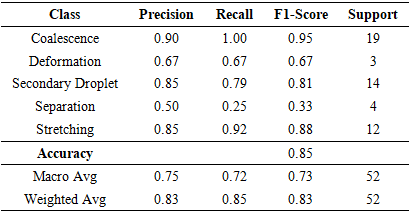

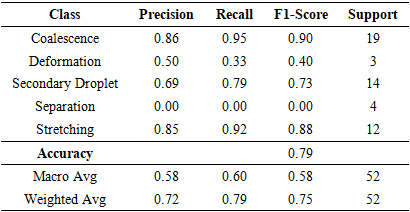

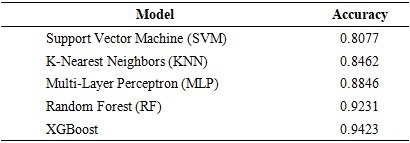

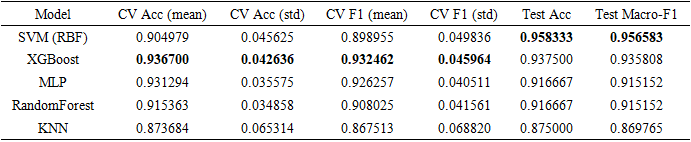

range (median = 45.45 [IQR 38.46–76.92]), indicating that viscous and surface tension forces dominate under these conditions, promoting the smooth merging of droplets. In contrast, Deformation exhibits the highest Reynolds numbers (mean = 162.68 ± 21.33), where inertial forces are sufficiently strong to overcome interfacial tension, resulting in significant droplet elongation or breakup. The secondary droplet regime also occurs at high Re values (mean = 137.86 ± 28.19), suggesting that instability at impact leads to satellite formation when inertia approaches or exceeds surface tension resistance.Intermediate behaviors such as Separation (mean = 95.70 ± 18.88) and stretching (mean = 89.77 ± 38.51) occupy transitional Reynolds number ranges, where neither viscous nor inertial forces are entirely dominant. These regions mark the thresholds between stable Coalescence and unstable fragmentation, emphasizing the sensitive dependence of collision outcomes on inertia. The broad interquartile range observed in stretching behavior further indicates variability in droplet deformation patterns, often linked to minor variations in impact velocity or alignment. Overall, the Reynolds number statistics in Table 5 provide quantitative evidence that increasing inertia systematically drives the progression from Coalescence to deformation and secondary droplet formation, aligning with both experimental findings and the trends captured by the LBM simulations.Table 6 presents the Weber number  distribution for each droplet behavior, highlighting the role of surface tension relative to inertial forces during collision. Lower Weber numbers correspond to Coalescence (mean = 0.221 ± 0.164), where surface tension dominates and droplets merge smoothly without breakup. In contrast, deformation and stretching display higher Weber numbers (mean = 4.874 ± 4.172 and 3.588 ± 3.168, respectively), indicating that increased inertia overcomes surface tension, causing significant droplet elongation and transient instability.The secondary droplet behavior appears in an intermediate Weber range (mean = 1.502 ± 1.405), suggesting a balance between inertial and capillary effects where breakup begins to occur. Meanwhile, Separation occurs at relatively low Weber numbers (mean = 0.709 ± 0.100), implying that droplets rebound rather than merge due to insufficient kinetic energy for Coalescence. Overall, these results demonstrate that as Weber number increases, the droplet behavior transitions systematically from stable Coalescence to Deformation and secondary droplet formation—consistent with the physical understanding of inertia-driven interface instability.We used five models: Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), K- Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Support Vector Machine (SVM), as shown in Tables 7-11. Input features included Reynolds number, Weber number, impact parameter, and surface tension. Each model was trained on 80% of the data and evaluated on the remaining 20%. XGBoost and Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy among all models, as summarized in Table 12. Detailed class-wise metrics are shown in subsequent tables.

distribution for each droplet behavior, highlighting the role of surface tension relative to inertial forces during collision. Lower Weber numbers correspond to Coalescence (mean = 0.221 ± 0.164), where surface tension dominates and droplets merge smoothly without breakup. In contrast, deformation and stretching display higher Weber numbers (mean = 4.874 ± 4.172 and 3.588 ± 3.168, respectively), indicating that increased inertia overcomes surface tension, causing significant droplet elongation and transient instability.The secondary droplet behavior appears in an intermediate Weber range (mean = 1.502 ± 1.405), suggesting a balance between inertial and capillary effects where breakup begins to occur. Meanwhile, Separation occurs at relatively low Weber numbers (mean = 0.709 ± 0.100), implying that droplets rebound rather than merge due to insufficient kinetic energy for Coalescence. Overall, these results demonstrate that as Weber number increases, the droplet behavior transitions systematically from stable Coalescence to Deformation and secondary droplet formation—consistent with the physical understanding of inertia-driven interface instability.We used five models: Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), K- Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Support Vector Machine (SVM), as shown in Tables 7-11. Input features included Reynolds number, Weber number, impact parameter, and surface tension. Each model was trained on 80% of the data and evaluated on the remaining 20%. XGBoost and Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy among all models, as summarized in Table 12. Detailed class-wise metrics are shown in subsequent tables.

|

|

|

|

|

|

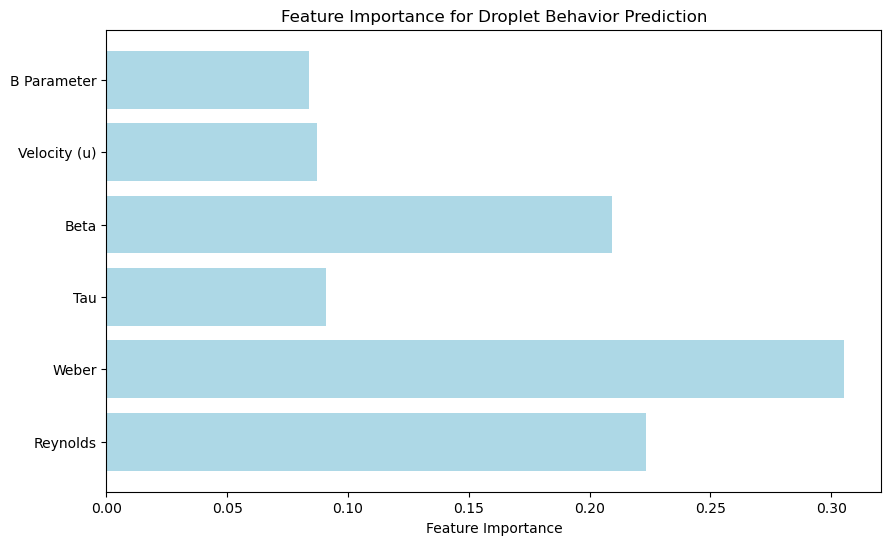

3.4. Improving Machine Learning Model

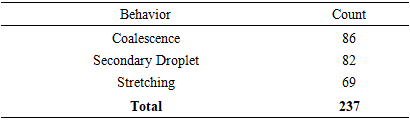

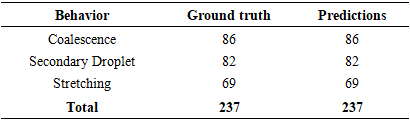

- We evaluated supervised models to predict droplet collision outcomes from primitive and dimensionless parameters. The evaluation set contained

videos after the following preprocessing: (i) Separation was merged into Stretching; (ii) Deformation rows were removed as shown in Table 13; (iii) all numeric features were coerced, and rows with missing features were dropped. Features included Viscosity, Surface Tension, Velocity

videos after the following preprocessing: (i) Separation was merged into Stretching; (ii) Deformation rows were removed as shown in Table 13; (iii) all numeric features were coerced, and rows with missing features were dropped. Features included Viscosity, Surface Tension, Velocity  Impact parameter (B), Density, Droplet Diameter, Reynolds, Weber, and Ohnesorge numbers. After preprocessing, the class counts were: Coalescence = 86, Secondary Droplet = 82, and Stretching = 69.

Impact parameter (B), Density, Droplet Diameter, Reynolds, Weber, and Ohnesorge numbers. After preprocessing, the class counts were: Coalescence = 86, Secondary Droplet = 82, and Stretching = 69.

|

|

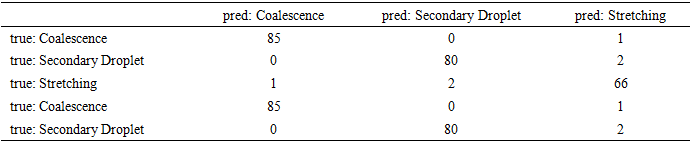

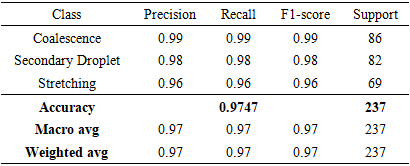

3.5. Trained Model Classification Performance

- The confusion matrix shows only 6 misclassifications out of 237 as shown in Table 15. 4 boundary errors between Secondary Droplet and Stretching. 2 boundary errors between Coalescence and Stretching. These cases cluster in intermediate Weber numbers and moderate B (impact parameter), consistent with visually ambiguous outcomes near regime boundaries.

|

|

|

Secondary Droplet achieving 0.98 for each metric

Secondary Droplet achieving 0.98 for each metric  and Stretching reaching 0.96 across all three measures

and Stretching reaching 0.96 across all three measures  as summarized in Table 17.

as summarized in Table 17.4. Analysis of the Relationship Between Flow Inertia and Surface Tension

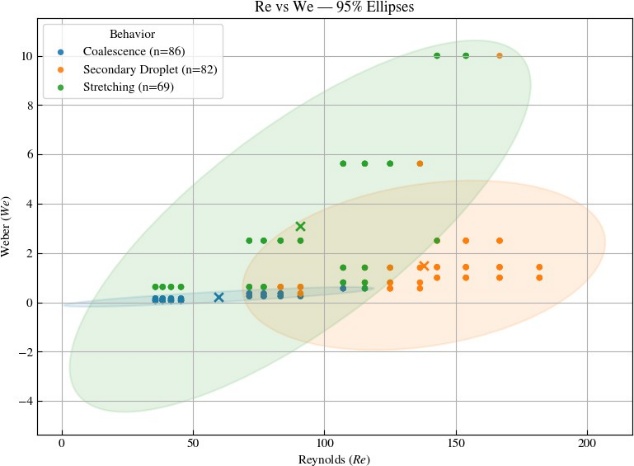

- In this section, we utilize the trained machine learning model to investigate the intricate relationship between flow inertia, characterized by the Reynolds number (Re), and surface tension, quantified by the Weber number (We), in determining the evolution and outcomes of droplet collisions. Figure 9 presents the elliptical boundaries derived from statistical analysis, which clearly demarcate the transitions between distinct droplet behaviors, including Coalescence, Stretching, and Secondary Droplet formation. These boundaries serve as a visual representation of how the interplay between inertial forces, driven by fluid flow, and interfacial forces, governed by surface tension, dictates the regimes of droplet dynamics. The elliptical shapes in Figure 9 effectively map the Re-We parameter space, highlighting regions where specific droplet behaviors dominate, thus providing a comprehensive overview of the physical mechanisms that control droplet interactions under varying flow conditions.

| Figure 9. Regime maps with decision boundaries classified by collision outcomes |

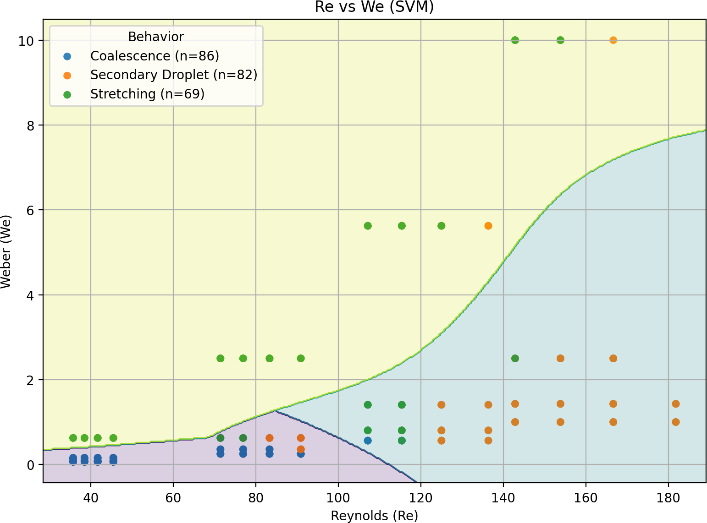

| Figure 10. Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification boundaries for droplet collision outcomes in the Reynolds number (Re) versus Weber number (We) parameter space |

and Reynolds number

and Reynolds number  are identified as the dominant predictors of droplet collision behavior, confirming that the balance between inertial and surface tension forces governs regime transitions. Surface tension

are identified as the dominant predictors of droplet collision behavior, confirming that the balance between inertial and surface tension forces governs regime transitions. Surface tension  viscosity

viscosity  and impact parameter

and impact parameter  also contribute, though to a lesser extent, indicating their secondary roles in refining boundary distinctions between stretching, coalescence, and secondary droplet formation. These results align with the physical understanding of droplet impact processes and provide transparency to the machine learning model’s internal decision structure.

also contribute, though to a lesser extent, indicating their secondary roles in refining boundary distinctions between stretching, coalescence, and secondary droplet formation. These results align with the physical understanding of droplet impact processes and provide transparency to the machine learning model’s internal decision structure.5. Conclusions

- This study presents a comprehensive investigation of the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) and its governing parameters, with direct comparisons to the Volume of Fluid (VOF) method under equivalent physical conditions. By incorporating a modified surface tension model and transferable velocity formulation, we developed an enhanced LBM framework capable of accurately reproducing five key droplet collision behaviors: stretching, Separation, secondary droplet formation, Coalescence, and Deformation. The simulations demonstrated that the proposed model successfully captures the dynamic transitions among these behaviors, revealing distinct Reynolds

and Weber

and Weber  number ranges associated with each regime.To validate the LBM framework, nine cases with matched parameters were simulated and compared against corresponding VOF results. The radius evolution curves exhibited strong agreement between both methods, confirming the physical consistency of the LBM predictions. These findings were further supported through analysis of dimensionless parameters, where both the

number ranges associated with each regime.To validate the LBM framework, nine cases with matched parameters were simulated and compared against corresponding VOF results. The radius evolution curves exhibited strong agreement between both methods, confirming the physical consistency of the LBM predictions. These findings were further supported through analysis of dimensionless parameters, where both the  and

and  values followed comparable trends across the two approaches.Statistical analysis of the simulation dataset indicated that merging the separation and stretching behaviors improved the robustness of classification outcomes. Using these refined categories, we trained multiple machine learning models and achieved high predictive accuracy, with the SVM (RBF kernel) model attaining 97% accuracy and balanced class performance across behaviors. Finally, the trained model was applied to explore the relationship between flow inertia

values followed comparable trends across the two approaches.Statistical analysis of the simulation dataset indicated that merging the separation and stretching behaviors improved the robustness of classification outcomes. Using these refined categories, we trained multiple machine learning models and achieved high predictive accuracy, with the SVM (RBF kernel) model attaining 97% accuracy and balanced class performance across behaviors. Finally, the trained model was applied to explore the relationship between flow inertia  and surface tension

and surface tension  in determining droplet collision outcomes. The resulting elliptical regime maps clearly delineate behavioral boundaries, offering deeper insight into the transitional physics governing multiphase droplet interactions.Overall, this research demonstrates that the sharp-interface LBM approach, combined with machine learning-based classification, provides a robust and data-informed framework for studying droplet dynamics and validating multiphase flow behaviors with high fidelity.

in determining droplet collision outcomes. The resulting elliptical regime maps clearly delineate behavioral boundaries, offering deeper insight into the transitional physics governing multiphase droplet interactions.Overall, this research demonstrates that the sharp-interface LBM approach, combined with machine learning-based classification, provides a robust and data-informed framework for studying droplet dynamics and validating multiphase flow behaviors with high fidelity.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Bridge to Academia Fellow Program through Virginia Tech for funding this research. Their investment in fostering academic scholarships and advancing computational science provided the resources and guidance necessary to complete this work.

Data Availability

- The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to project and storage limitations, but they are available from the author upon reasonable request. Interested readers and researchers may contact the corresponding author to obtain access to the data supporting the findings of this work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML

are indicated. Concept follows the single-phase LBM force treatment where surface tension is applied as an external force in the collision step

are indicated. Concept follows the single-phase LBM force treatment where surface tension is applied as an external force in the collision step

and

and  The interaction occurs in a low-inertia regime, characterized by

The interaction occurs in a low-inertia regime, characterized by  and

and  , where surface tension dominates over inertial forces. The figure illustrates the maximum elongation of the droplets prior to the transition stage leading to Coalescence or rebound

, where surface tension dominates over inertial forces. The figure illustrates the maximum elongation of the droplets prior to the transition stage leading to Coalescence or rebound

and

and  The interaction occurs in a moderate-inertia regime, characterized by

The interaction occurs in a moderate-inertia regime, characterized by  and

and  where inertial forces begin to overcome surface tension, resulting in droplet breakup. The figure captures the moment of satellite droplet formation following the maximum elongation phase

where inertial forces begin to overcome surface tension, resulting in droplet breakup. The figure captures the moment of satellite droplet formation following the maximum elongation phase

and

and  . The flow conditions, characterized by

. The flow conditions, characterized by  and

and  , indicate a surface-tension-dominated regime where the droplets merge into a single continuous interface without the formation of secondary structures

, indicate a surface-tension-dominated regime where the droplets merge into a single continuous interface without the formation of secondary structures

and droplet diameter

and droplet diameter  The conditions, defined by

The conditions, defined by  and

and  correspond to a strongly surface-tension-dominated regime, where the droplets fail to coalesce and instead rebound after partial Deformation

correspond to a strongly surface-tension-dominated regime, where the droplets fail to coalesce and instead rebound after partial Deformation

with

with  and

and  The VOF result, using

The VOF result, using  yields

yields  and

and  The comparison demonstrates consistent droplet stretching behavior across both numerical frameworks

The comparison demonstrates consistent droplet stretching behavior across both numerical frameworks