-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Applied Mathematics

p-ISSN: 2163-1409 e-ISSN: 2163-1425

2012; 2(1): 1-7

doi: 10.5923/j.am.20120201.01

Self-Similar Cylindrical Ionizing Shock Waves in a Non-Ideal Gas with Radiation Heat-Flux

J. P. Vishwakarma , Mahendra Singh

Dept. of Mathematics and Statistics, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University Gorakhpur-273009, India

Correspondence to: J. P. Vishwakarma , Dept. of Mathematics and Statistics, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University Gorakhpur-273009, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Self-similar flows behind a gas-ionizing cylindrical shock wave, with radiation heat flux, in a non-ideal gas are studied. The ionizing shock is assumed to be propagating in a medium at rest with constant density permeated by an azimuthal magnetic field. The electrical conductivity of the gas is infinite behind shock and zero ahead of it. Effects of the non-idealness of the gas, the radiation flux and the rate of energy input from the inner contact surface (or piston) on the flow-field behind the shock and on the shock propagation are investigated.

Keywords: IonizingShock Wave, Non-Ideal Gas, Spatially Variable Magnetic Field, Similarity Solutions, Radiation Heat-Flux

Cite this paper: J. P. Vishwakarma , Mahendra Singh , "Self-Similar Cylindrical Ionizing Shock Waves in a Non-Ideal Gas with Radiation Heat-Flux", Applied Mathematics, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.am.20120201.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The influence of radiation on a shock wave and on the flow-field behind the shock front has always been of great interest, for instance, in the field of nuclear power and space research. Consequently, similarity models for classical blast wave problems have been extended by taking radiation into account (Elliott[1], Wang[2], Helliwell[3], Ni Castro[4], Ghoniem et al.[5]). Elliott[1] considered the explosion problem by introducing the radiation flux in its diffusion approximation. Wang[2] discussed the piston problem with radiative heat transfer in the thin and thick limits and also in the general case with idealized two direction approximation. Ghoniem et al.[5] obtained a self-similar solution for spherical explosion taking into account the effects of both conduction and radiation in the two limits of Rosselandradiative diffusion and Plank radiative emission.Since at high temperatures that prevail in the problems associated with shock waves a gas is partially ionized, electromagnetic effects may also be significant. A complete analysis of such a problem should therefore consist of the study of the gasdynamic flow and the electromagnetic and radiation fields simultaneously. A number of problem relating to shock wave propagation in a perfect gas with radiative and magnetohydrodynamic effects have been studied (see, for example, Singh and Mishra[6], Vishwakarma et al.[7], Singh et al.[8], Ganguly and Jana[9]). The assumption that the gas is ideal is no more valid when the flow takes place at extreme conditions. In recent years, several studies have been performed concerning the problem of strong shock waves in non-ideal gases, in particular, by Anisimov and Spiner[10], Rangarao and Purohit[11], Wu and Roberts[12], Madhumita and Sharma[13], Arora and Sharma[14] and Vishwakarma and Nath[15,16] among others. Anisimov and Spiner[10] have taken an equation of state for a low density non-ideal gas in a simplified form, and studied the effects of non-idealness of the gas on the problem of point explosion. Rangarao and Purohit[11] have studied the self-similar flows of a non-ideal gas driven by an expanding piston and obtained approximate analytic and numerical solutions by taking the equation of state suggested by Anisimov and Spiner[10]. Vishwakarma and Nath[15] have obtained similarity solutions for the flow behind an exponential shock by taking the same equation of state for the medium. Roberts and Wu[17, 18] have used an equivalent equation of state to study the shock wave theory of sonoluminescence. Vishwakarma et al.[19] too adopted this as their model of a non-ideal gas to obtain the self-similar solutions for the flow behind a magnetogasdynamic cylindrical shock wave propagating in a rotating gas in presence of an azimuthal magnetic field. They have taken the electrical conductivity of the initial medium and the medium behind the shock to be infinite. But, in many practical cases the medium may be of low conductivity which becomes highly conducting due to passage of a strong shock. Such a shock wave is called a gas-ionizing shock or, simply ionizing shock. The propagation of ionizing shock has been studied by Greenspan[20], Greifinger and Cole[21], Christer[22], Rangarao and Ramana[23] and Singh[24] in a perfect gas.We, in the present work, extended the problem treated by Singh[24] by taking the medium to be a non-ideal gas instead of an ideal gas. The problem of line explosion with time dependent energy release and radiation in the presence of an azimuthal magnetic field is considered due to its relevance to the experiments on pinch effect and exploding wires. A gas-ionizing cylindrical shock wave, generated by line explosion, is propagated in the non-ideal gas. The counter pressure (the pressure ahead of the shock) is taken into account. The radiation pressure and radiation energy are considered very small in comparison to material pressure and energy, respectively, and therefore only radiation flux is taken into account. A diffusion model for an optically thick grey gas is assumed. The ambient azimuthal magnetic field is assumed to be varying as some power of the distance from the axis of symmetry. In order to obtain similarity solutions of the problem it is necessary to take the density of the ambient non-ideal gas to be a constant. It is observed that the shock velocity decreases with the ambient magnetic field. Also, the rate of energy input to the flow behind the shock, the radiation flux and the non-idealness of the gas are found to have significant effects on the propagation of the shock and the flow-field behind it.

2. Basic Equations and Boundary Conditions

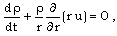

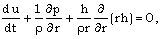

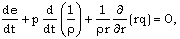

- The fundamental equations governing the unsteady and cylindrically symmetric motion of an inviscid, perfectly conducting and non-ideal gas in which the effects of radiation flux and azimuthal magnetic field may be significant, can be written as (Christer and Helliwell[25], Vishwakarma and Pandey[26], Gretler and Wehle[27]).

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

| (2.4) |

Here,

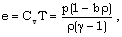

Here,  is the density, p the pressure, u the radial velocity, h the azimuthal magnetic field, q the radiation heat flux, t the time, r the distance from the axis of symmetry, and e the internal energy. The magnetic permeability of the medium is taken to be unity. In most of the cases the propagation of shock waves arise in extreme conditions under which the assumption that the gas is ideal is not a sufficiently accurate description. To discover how deviations from the ideal gas can affect the solutions, we adopt a simple model. We assume that the gas obeys a simplified van der Waals equation of state of the form (Roberts and Wu,[17,18])

is the density, p the pressure, u the radial velocity, h the azimuthal magnetic field, q the radiation heat flux, t the time, r the distance from the axis of symmetry, and e the internal energy. The magnetic permeability of the medium is taken to be unity. In most of the cases the propagation of shock waves arise in extreme conditions under which the assumption that the gas is ideal is not a sufficiently accurate description. To discover how deviations from the ideal gas can affect the solutions, we adopt a simple model. We assume that the gas obeys a simplified van der Waals equation of state of the form (Roberts and Wu,[17,18]) | (2.5) |

| (2.6) |

is the gas constant,

is the gas constant,  is the specific heat at constant volume and

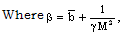

is the specific heat at constant volume and  is the ratio of specific heats. The constant b is the ‘van der Waals excluded volume’; it places a limit,

is the ratio of specific heats. The constant b is the ‘van der Waals excluded volume’; it places a limit,  , on the density of the gas.For an isentropic change of state of the non-ideal gas, we may calculate the so called speed of sound in non-ideal gas as followswhere the subscript ‘s’ refers to the process of constant entropy.Assuming local thermodynamic equilibrium and a diffusion model for an optically thick grey gas (Pomraning[28]), the differential approximation of the radiation transport equation can be written in the following form

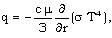

, on the density of the gas.For an isentropic change of state of the non-ideal gas, we may calculate the so called speed of sound in non-ideal gas as followswhere the subscript ‘s’ refers to the process of constant entropy.Assuming local thermodynamic equilibrium and a diffusion model for an optically thick grey gas (Pomraning[28]), the differential approximation of the radiation transport equation can be written in the following form | (2.8) |

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, c the velocity of light and

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, c the velocity of light and  the Rosseland mean free path for radiation. The assumption of an optically thick grey gas is physically consistent with the neglect of radiation pressure and radiation energy in the equation system (2.1)-(2.4) (Ni-Castro [4]).Following Wang[2], we take

the Rosseland mean free path for radiation. The assumption of an optically thick grey gas is physically consistent with the neglect of radiation pressure and radiation energy in the equation system (2.1)-(2.4) (Ni-Castro [4]).Following Wang[2], we take | (2.9) |

are constants. It will be seen later that the exponents

are constants. It will be seen later that the exponents  must satisfy the similarity requirements. The self-similarity condition puts no constraints on specification of the density dependence of

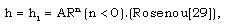

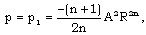

must satisfy the similarity requirements. The self-similarity condition puts no constraints on specification of the density dependence of  .We assume that a cylindrical shock is propagating in the medium and the flow variables immediately ahead of the shock front are

.We assume that a cylindrical shock is propagating in the medium and the flow variables immediately ahead of the shock front are  | (2.10a) |

| (2.10b) |

| (2.10c) |

| (2.10d) |

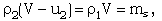

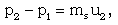

| (2.11a) |

| (2.11b) |

| (2.11c) |

| (2.11d) |

is the heat flux exchanged between the flow-field and the shock front. The jump conditions (2.11) are not sufficient to determine all the flow variables at the shock front. Hence, one variable stays undetermined there. This difficulty is removed by assuming the shock front to isothermal that is,

is the heat flux exchanged between the flow-field and the shock front. The jump conditions (2.11) are not sufficient to determine all the flow variables at the shock front. Hence, one variable stays undetermined there. This difficulty is removed by assuming the shock front to isothermal that is, | (2.11e) |

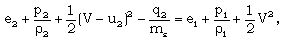

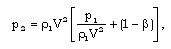

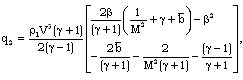

| (2.12a) |

| (2.12b) |

| (2.12c) |

| (2.12d) |

| (2.12e) |

| (2.12f) |

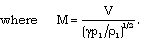

is the parameter of non-idealness of the gas. Here, M is the shock-Mach number referred to the frozen speed of sound

is the parameter of non-idealness of the gas. Here, M is the shock-Mach number referred to the frozen speed of sound  and

and  the Alfven-Mach number.The shock-Mach number Me referred to the speed of sound in non-ideal gas

the Alfven-Mach number.The shock-Mach number Me referred to the speed of sound in non-ideal gas  and the Alfven-Mach number

and the Alfven-Mach number  are given by

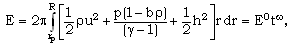

are given by The total energy of the flow-field behind the shock is not constant, but assumed to be time dependent and varying as (Rogers[34], Freeman[35])

The total energy of the flow-field behind the shock is not constant, but assumed to be time dependent and varying as (Rogers[34], Freeman[35]) | (2.14) |

correspond to the class in which the total energy increases with time. This increase can be achieved by the pressure exerted on the fluid by an expanding surface (a contact surface or a piston). This surface may be, physically, the surface of the stellar corona or the condensed explosives or the diaphragm containing a very high-pressure driver gas. By sudden expansion of the stellar corona or the detonation products or the driver gas into the ambient gas, a shock wave is produced in the ambient gas. The shocked gas is separated from this expanding surface which is a contact discontinuity. This contact surface acts as a ‘piston’ for the shock wave. Thus the flow is headed by a shock front and has an expanding surface as the inner boundary. A situation very much of the same kind may prevail during the formation of a cylindrical spark channel from exploding wires. In addition, in the usual cases of spark break down, time-dependent energy input is a more realistic assumption than instantaneous energy input (Freeman and Cragges [36], Director and Dabora [37]).The expression for the total energy of the non-ideal gas behind the shock is given by

correspond to the class in which the total energy increases with time. This increase can be achieved by the pressure exerted on the fluid by an expanding surface (a contact surface or a piston). This surface may be, physically, the surface of the stellar corona or the condensed explosives or the diaphragm containing a very high-pressure driver gas. By sudden expansion of the stellar corona or the detonation products or the driver gas into the ambient gas, a shock wave is produced in the ambient gas. The shocked gas is separated from this expanding surface which is a contact discontinuity. This contact surface acts as a ‘piston’ for the shock wave. Thus the flow is headed by a shock front and has an expanding surface as the inner boundary. A situation very much of the same kind may prevail during the formation of a cylindrical spark channel from exploding wires. In addition, in the usual cases of spark break down, time-dependent energy input is a more realistic assumption than instantaneous energy input (Freeman and Cragges [36], Director and Dabora [37]).The expression for the total energy of the non-ideal gas behind the shock is given by  | (2.15) |

3. Similarity Solutions

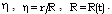

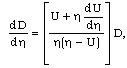

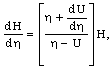

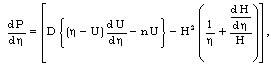

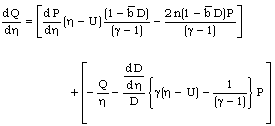

- For self-similar motions, the system of partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.4), (2.8) reduces to a system of ordinary differential equations in new unknown functions of the similarity variable

. Let us derive these equations. To do this we represent the solution of the partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.4), (2.8) in terms of the products of scale functions and the new unknown functions of the similarity variable

. Let us derive these equations. To do this we represent the solution of the partial differential equations (2.1)-(2.4), (2.8) in terms of the products of scale functions and the new unknown functions of the similarity variable  The pressure, density, velocity, magnetic field, radiation heat flux, and length scales are not all independent of each other. If we choose R and

The pressure, density, velocity, magnetic field, radiation heat flux, and length scales are not all independent of each other. If we choose R and  as the basic scales, then the quantity

as the basic scales, then the quantity  can serve as the velocity scale,

can serve as the velocity scale,  as the pressure scale,

as the pressure scale,  as the magnetic field scale, and

as the magnetic field scale, and  as the radiation flux scale. This does not limit the generality of the solution, as the scale is only defined to within a numerical coefficient which can always be included in the new unknown function. We seek a solution of the form (Abdel-Raouf and Gretler[38], Ghoniem et al.[5])

as the radiation flux scale. This does not limit the generality of the solution, as the scale is only defined to within a numerical coefficient which can always be included in the new unknown function. We seek a solution of the form (Abdel-Raouf and Gretler[38], Ghoniem et al.[5]) | (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

| (3.3) |

| (3.4) |

| (3.5) |

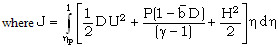

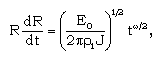

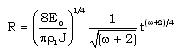

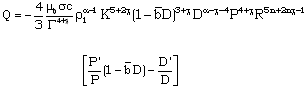

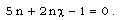

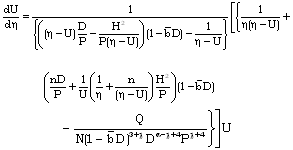

only.Applying the similarity transformations (3.1) to (3.5) to the relation (2.15), we find that the motion of the shock front is given by the equation

only.Applying the similarity transformations (3.1) to (3.5) to the relation (2.15), we find that the motion of the shock front is given by the equation | (3.6) |

(3.7)Equation (3.6) can be written as

(3.7)Equation (3.6) can be written as | (3.8) |

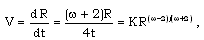

| (3.9) |

| (3.10) |

| (3.11) |

| (3.12) |

| (3.13) |

| (3.14) |

| (3.15) |

| (3.17) |

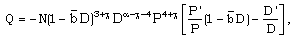

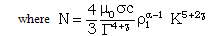

Therefore,

Therefore,  .Therefore, equation (3.17) becomes

.Therefore, equation (3.17) becomes | (3.18) |

| (3.19) |

| (3.20) |

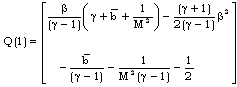

| (3.21a) |

| (3.21b) |

| (3.21c) |

| (3.21d) |

| (3.21e) |

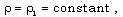

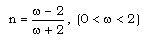

, similarity solution exists only when

, similarity solution exists only when  is a constant, that is only when the initial density

is a constant, that is only when the initial density  is constant. The problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas is different from that of the perfect gas problem. In the latter case, similarity solution exists for initial density varying as some power of distance (Vishwakarma et al[7], Elliott[1], Christer and Helliwell[25], and Purohit[39]). But, it is not true for the problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas. In addition to the shock conditions (3.21), the condition to be satisfied at the inner boundary surface is that the velocity of the fluid is equal to the velocity of inner boundary itself. This kinematic condition, from equations (3.1) and (3.12), can be written as

is constant. The problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas is different from that of the perfect gas problem. In the latter case, similarity solution exists for initial density varying as some power of distance (Vishwakarma et al[7], Elliott[1], Christer and Helliwell[25], and Purohit[39]). But, it is not true for the problem with the flow of a non-ideal gas. In addition to the shock conditions (3.21), the condition to be satisfied at the inner boundary surface is that the velocity of the fluid is equal to the velocity of inner boundary itself. This kinematic condition, from equations (3.1) and (3.12), can be written as | (3.22) |

to obtain D, H, P, Q, and U.For exhibiting the numerical solutions, it is convenient to write the flow-variables in the following non-dimensional form as

to obtain D, H, P, Q, and U.For exhibiting the numerical solutions, it is convenient to write the flow-variables in the following non-dimensional form as | (3.23) |

| (3.24) |

| (3.25) |

| (3.26) |

| (3.27) |

4. Results and Discussion

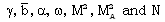

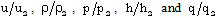

- The non-dimensional flow variables

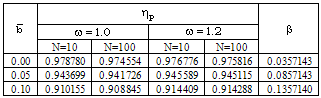

are obtained by numerical integration of the equations (3.12) to (3.15) and (3.20) with the boundary conditions (3.21). For the purpose of numerical calculations, the values of constant parameters are taken as (Roberts and Wu[17], Elliott[1], Singh and Mishra[6], Rosenau[29]):

are obtained by numerical integration of the equations (3.12) to (3.15) and (3.20) with the boundary conditions (3.21). For the purpose of numerical calculations, the values of constant parameters are taken as (Roberts and Wu[17], Elliott[1], Singh and Mishra[6], Rosenau[29]):

and N=10, 100. The Value

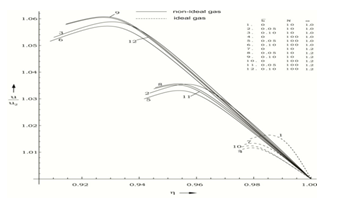

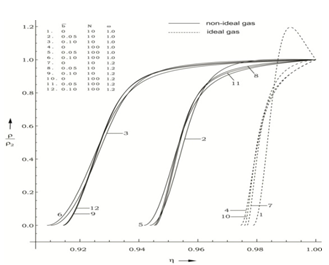

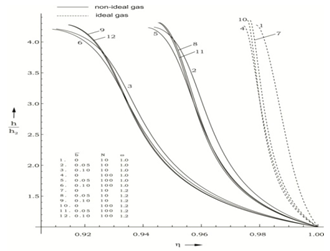

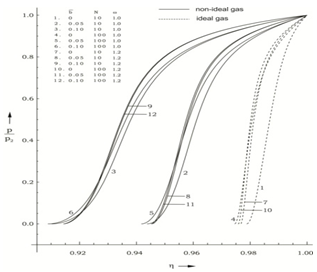

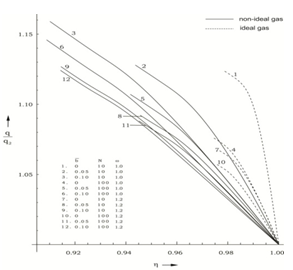

and N=10, 100. The Value  corresponds to the case of a perfect gas. Figures 1-5 show the variation of the flows variables

corresponds to the case of a perfect gas. Figures 1-5 show the variation of the flows variables  with

with  at various values of the parameters

at various values of the parameters  It is shown that, as we move inward from the shock front towards the inner contact surface, the reduced magnetic field

It is shown that, as we move inward from the shock front towards the inner contact surface, the reduced magnetic field  and the reduced radiation heat flux

and the reduced radiation heat flux  increase and the reduced pressure

increase and the reduced pressure  decreases. Also, as we move inwards from the shock surface, the reduced velocity

decreases. Also, as we move inwards from the shock surface, the reduced velocity  increases, and starts to decrease after attaining a maximum near the inner contact surface. The reduced density

increases, and starts to decrease after attaining a maximum near the inner contact surface. The reduced density  decreases from the shock front to the inner contact surface in all the cases except in the case

decreases from the shock front to the inner contact surface in all the cases except in the case  , N=10,

, N=10,  where it increases and starts to decrease after attaining a maximum.The effects of an increase in the value of the parameter of non-idealness of the gas

where it increases and starts to decrease after attaining a maximum.The effects of an increase in the value of the parameter of non-idealness of the gas  are (from table 1 and figures 1-5)

are (from table 1 and figures 1-5) | Figure 1. variation of non-dimensional velocity  with non-dimensional distance with non-dimensional distance  |

| Figure 2. variation of non-dimensional density with non-dimensional distance with non-dimensional distance  |

| Figure 3. variation of non-dimensional magnetic field  with non-dimensional distance with non-dimensional distance  |

| Figure 4. variation of non-dimensional pressure  with non-dimensional distance with non-dimensional distance |

| Figure 5. variation of non-dimensional radiation flux  with non-dimensional distance with non-dimensional distance  |

i.e. to decrease the shock strength. This is the same as concluded in (i) above. Therefore, the non-idealness of the gas has decaying effect on the shock wave.(iii). to increase the reduced pressure

i.e. to decrease the shock strength. This is the same as concluded in (i) above. Therefore, the non-idealness of the gas has decaying effect on the shock wave.(iii). to increase the reduced pressure  ;(iv). to increase the reduced velocity

;(iv). to increase the reduced velocity  and reduced density

and reduced density  , in general; and (v). to decrease the reduced magnetic field

, in general; and (v). to decrease the reduced magnetic field  and the reduced heat flux

and the reduced heat flux  .The effects of an increase in the value of radiation parameter N are(i). to decrease the reduced velocity

.The effects of an increase in the value of radiation parameter N are(i). to decrease the reduced velocity  and reduced radiation heat flux

and reduced radiation heat flux  (see figures 1 and 5);(ii). to increase the reduced pressure

(see figures 1 and 5);(ii). to increase the reduced pressure  (figure 4); and (iii). to decrease the value of

(figure 4); and (iii). to decrease the value of  (table 1), i.e. to decrease the shock strength. This decrease in the shock strength is due to the fact that the transport of energy through radiation is faster at higher values of N.The effects of an increase in the value of the exponent in the law for energy input

(table 1), i.e. to decrease the shock strength. This decrease in the shock strength is due to the fact that the transport of energy through radiation is faster at higher values of N.The effects of an increase in the value of the exponent in the law for energy input  (or the exponent in the law for initial magnetic field n) are (i). to decrease the reduced magnetic field

(or the exponent in the law for initial magnetic field n) are (i). to decrease the reduced magnetic field  and the reduced radiation heat-flux

and the reduced radiation heat-flux  , but the effect is small when N=100 (see the figure 3 and 5);(ii). to increase the reduced pressure

, but the effect is small when N=100 (see the figure 3 and 5);(ii). to increase the reduced pressure  , but the effect is small when N=100 (see figure 4);(iii). to decrease the reduced velocity

, but the effect is small when N=100 (see figure 4);(iii). to decrease the reduced velocity  when N=10, but to increase it when N=100 (see figure 1). The above results ((i), (ii), (iii)) show that the effects of an increase in

when N=10, but to increase it when N=100 (see figure 1). The above results ((i), (ii), (iii)) show that the effects of an increase in  are reduced or reversed by an increase in the radiation parameter N; and (iv). to increase the value of

are reduced or reversed by an increase in the radiation parameter N; and (iv). to increase the value of  (see table 1), in general, i.e. to decrease the distance between the inner contact surface and the shock front. This shows that an increase in the value of

(see table 1), in general, i.e. to decrease the distance between the inner contact surface and the shock front. This shows that an increase in the value of  increases the shock strength. This is due to the fact that an increase in the value of

increases the shock strength. This is due to the fact that an increase in the value of  increases the rate of energy input to the flow between the inner contact surface and the shock front.

increases the rate of energy input to the flow between the inner contact surface and the shock front.

|

5. Conclusions

- In the present work, similarity solutions are obtained for the flow field behind a gas-ionizing cylindrical shock wave propagating in a non-ideal gas in presence of an azimuthal magnetic field, with radiation heat-flux and time dependent energy input. It is observed that as the shock propagates, its velocity V decreases with the ambient magnetic field

. It is investigated that an increase in the parameter of non-idealness of the gas

. It is investigated that an increase in the parameter of non-idealness of the gas  , or in the exponent for energy input

, or in the exponent for energy input  , or in the radiation parameter N modifies the distribution of the flow variables behind the shock, and the non-idealness of the gas or the presence of the radiation heat-flux decays the shock wave. It is also investigated that the effects of an increase in the rate of energy input (i.e. an increase in

, or in the radiation parameter N modifies the distribution of the flow variables behind the shock, and the non-idealness of the gas or the presence of the radiation heat-flux decays the shock wave. It is also investigated that the effects of an increase in the rate of energy input (i.e. an increase in  ) are reduced or reversed by an increase in the radiation parameter N.

) are reduced or reversed by an increase in the radiation parameter N. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML , and the density ratio across the shock front

, and the density ratio across the shock front  for

for

, and different values of

, and different values of