P. Mounjouenpou 1, J. Amang A. Mbang 1, E. J. Nossi 2, S. Bassanaga 3, S. A. Maboune Tetmoun 1, D. Achukwi 1, N. Woin 1

1Institut de Recherche Agricole pour le Développement (IRAD), BP 2067, Yaoundé, Cameroun

2Université de Yaoundé 1, Département de Sociologie, BP 337 Yaoundé, Cameroun

3Groupement d’Initiative CONACFAC, B.P. 34434 Yaoundé Cameroun

Correspondence to: P. Mounjouenpou , Institut de Recherche Agricole pour le Développement (IRAD), BP 2067, Yaoundé, Cameroun.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Women in the subdivisions of Mbalmayo and Mbangassina, Cameroon are important in the cocoa value chain. At the same time, Women and children are the most suffering of poverty, malnutrition, food insecurity in rural area. Normally, women should be able to benefit from these activities, but are unable to do so, due to inadequacies in capacity building to transform cocoa in a way that can sustain both resources and people. Strengthening capacities of women cocoa-farmers is underscored to be central in ensuring sustainable solutions to the problem of malnutrition, food insecurity and declining income of cocoa farmers, as well as empower female leadership skills. This study consists to build capacities of women cocoa farmers of Mbalmayo and Mbangassina regions for sustainable improvement of their livelihoods. Through field trips, meeting with village groupings and inquiries from individuals and groups, 185 women were interviewed and trained on the manufacture of cocoa butter, cocoa powder and soy-chocolate drink. Cocoa butter was among others, the most adopted innovative product, followed by cocoa powder and soy-chocolate drink. Due to that training, women have become more efficient in their household management. She have started generate more income due to the commercialization of the surplus of process product, and also contribute to the household charges. This study highlighted some of challenges affecting livelihoods of women cocoa farmers which are mainly the availability of cocoa beans because cocoa farm belongs to men, and the problem of inadequate material for local transformation.

Keywords:

Capacity Building, Women cocoa-farmers, Mbalmayo and Mbangassina communities, Cocoa derived product, Malnutrition, Food insecurity

Cite this paper: P. Mounjouenpou , J. Amang A. Mbang , E. J. Nossi , S. Bassanaga , S. A. Maboune Tetmoun , D. Achukwi , N. Woin , Cocoa Value Chain and Capacity Building of Women Cocoa-farmers for Sustainable Improvement of Their Livelihoods: The Case of Mbangassina and Mbalmayo, Cameroon, Advances in Life Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 185-195. doi: 10.5923/j.als.20140404.01.

1. Introduction

Within the developed communities, capacity strengthening is debated and developing countries in particular are encouraged to strengthen the capacities within their public and private institutions in order to address challenges of sustainable development [1, 2]. Capacity strengthening is the enhancement of existing human and institutional capabilities to implement policies and other activities for development. It is a process undertaken externally or internally with the aim of improving the performances of regional and national development activities. The process of capacity strengthening includes strengthening of skills and competencies, training of individuals, and infrastructural development of research and development institutions [3]. According to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Capacity strengthening is synonymously used with capacity building and is stated to be a continuous development process involving many stakeholders; who among others include governmental, non-governmental organizations, local communities and academics who steer development. Capacity building is also considered to be essential for sustainable development because it enables people to optimally allocate and effectively use factors of production (i.e., land, labour and capital) as well as making management and power relation decisions [4, 5]. Studies have shown that differences in education levels as an aspect of capacity building influences labour productivity with regard to investment decision making. In a study [6], four years’ of schooling was found to increase farmers’ output by 8.7% while in another study [7], they was found that farmers invested on high pay-off inputs such as hybrids based on their levels of educational. Fletcher [8] suggests that the benefits of capacity building are best observed at community level and he argues that at this level, capacity building enhances the communities’ moral sense of duty with respect to resource use. Agricultural productivity in sub-Saharan Africa has declined due to many reasons among which are limited training opportunities, aging of qualified staff and disproportionate recruitment of qualified staff in institutions charged with development [9]. The situation is even more acute in the agriculture sector, particularly with cocoa farmers.About 50% of the Cameroonian population lives in the rural areas with agriculture as their major activity: Cameroon produces more than 200 000 tons of cocoa per year. About 95% of this production is exported. More than 5 million persons live exclusively on cacao farming. Following the drop in the sale prices of cacao in the international market, cacao farmers experienced an unpleasant drastic drop in their incomes. This was later followed by an increase in poverty rate which brought about food insecurity and malnutrition in rural areas. Food insecurity affects almost 25% of the population. According to the FAO statistics, the energy consumption in rural areas is lower than the average consumption in developing countries (approximately 2300 against 2600 Kcal/person/day). If urgent and adapted responses are not put in place, more than 2 million children under the age of 5 will continuously suffer of stunting in the next 10 years and more than 218,000 will die of malnutrition [10]. Mbangassina and Mbalmayo are two important pools of Cameroonian cocoa production. Cocoa is a very important cash crop in these 2 regions. These two areas of production are considered as new orchards with increasing production, but poverty rate and food insecurity are high. Child malnutrition is recurrent and the energy consumption is very low. Of this fact, it becomes very important to encourage these producers to use cocoa at local level for their own consumption in order to ensure their food self-sufficiency. In these areas, the main problem of the majority of women is exclusion. Women are not involved in the sale of cocoa beans. They work in the plantations and also actively participate in the cocoa post-harvest handling (harvesting, pod-breaking, fermentation, cocoa drying and packaging). But the commercialization of cocoa is at the exclusive control of the husband who does not cheer benefit with their wives. Women thus feel excluded from the proceeds since they cannot and may not benefit much from incomes derived from cocoa farming. Consequently, there is increased need for strengthening of women capacity which includes identification of capacity gaps and existing knowledge in order to have women who can have their own business and then, become more independent and dynamic. This study is therefore aimed at building women capacities that are the main actors in household diet, in order to find sustainable solutions to the problem of malnutrition, food insecurity, declining revenues of cocoa farmers, and to increase women earnings and leadership role within their households. The training and enhancement of awareness in women on the production of cocoa butter, cocoa powder and soy chocolate drink can be regarded as an appropriate response for improve cocoa farmers’ wellbeing.

2. Methodology and Materials

The methodology used consisted of field visits, surveys with women cocoa farmers (individual interview) and women associations (focus group discussions), training and monitoring of women participants). The gender approach used was that of the model of AWARD (African Women in Agricultural and Research Development).

2.1. Study Areas

Two important pools of Cameroonian cocoa production have been selected for this study: Mbangassina and Mbalmayo. Whereas Mbangassina is a far off subdivision which is highly agricultural, Mbalmayo is a more developed sub division along the main road between Yaounde and Kye-ossi (border between Cameroon, Gabon and Central Africa).

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Several participatory methodologies were employed for data collection. These were Informative Meeting, individual interview, focused group discussions (FGDs) [11, 12, 13], SWOT analysis [14]. Other information was obtained through observations during the field visits

2.2.1. Informative Meeting

Informative Meeting was convened with the administrative authorities and assembly of villagers. During this preliminary visit, the village heads, development committee and other notables were contacted as well as some administrative authorities. During the meeting (Figure 1), people were informed on the expected results of the project as well as profit that can attract the villagers. It was also an opportunity to collect information on the localities such as administrative data (different villages, statistics of the villages: number of people, number of households), population data (different ethnic groups, influential families,...), cocoa production (statistic on cocoa production, data on cocoa post-harvest), the most important cacao-famers in each region, as well as the various women's associations and women cocoa farmers.  | Figure 1. Meeting with villagers: Nseng-Elong and Bialenguéna |

2.2.2. Interview on Individual Basis

Individual inquiry (Figure 2) was based on interviewing each cocoa-farmer with the aim of gathering the following information: composition of the family, feeding habits, cocoa production, post-harvest handling, cocoa processing, and sale of cocoa. | Figure 2. Individual Interview at Ekombitié |

2.2.3. Focus Group Discussions

The focus group is a technique of inquiry, which permits for the interviewing of several persons belonging to the same group at the same time. The focused group discussions (Figure 3) were facilitated through translations from French to local language when need. Focus group was aimed at collecting information from farmers in groups: function, dynamics, problems encountered … by women association. At least 5 most active women were invited to the Focus Group discussions.  | Figure 3. Focus Group discussions at Ngat-Bané |

2.3. Data Analysis

The responses obtained from the interviewees were analyzed using content analysis in relation to the study objectives [7, 5]. Numeric data from inquiry were analyzed through the use of software SphinxME11. SWOT analyses were accomplished to discuss what they understood to “Strengths, Weakness, threats and Opportunity in respect of sustainable improving of livelihoods”. After which, the outcomes were jointly discussed in a plenary and endorsed.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Exploratory Study of the Villages

Mbalmayo is located approximately 50 km south of Yaounde, this town is the administrative capital of the” Nyong and So'o” division. Mbalmayo is one of the 6 subdivisions which constitute the Nyong and so'o division, among Akoeman, Dzeng, Mengueme, Ngomedzap and Nkolmetet. The Mbalmayo Subdivision is composed of fifteen villages. This subdivision is highly populated by 2 large groupings namely: Bane North and Bane Center. There are intense cocoa – farming activities in this Subdivision with an annual tonnage estimated at 1000 tons/year. The Mbangassina Subdivision counts twenty villages and three major groupings made up of: Tsinga, Kombe, and Bonjo. The local ethnic groups are the Baveuk, Djanti, Mvoute and Sanaga which constitute the indigenous peoples and are the majority groups. There is also a strong colonisation of other ethnic groups to the conquest of fertile land: Etong, Bamiléké, Menguissa, Yambassa and Bafia. Mbangassina village is composed of 8 large families: the Bialenguéna, Biamasse, Bitengue, Sarah, Biondo, Badjoa, Biombete, and Biongah families. The annual tonnage is about 1500 tons.The cocoa production capacity varies depending on the village. According to the importance of cocoa production and the geographical location of the village within the subdivision, 6 villages were selected in Mbalmayo subdivision and 5 villages in Mbangassina Subdivision. These villages in the two Subdivisions are not heavily populated; they count about 200 persons per village (Table 1).| Table 1. Population Structure according to the selected villages |

| | Subdivision | Selected village | Population (habitants) | | Mbalmayo | Ngat-Bané | 100 | | Memiam | 150 | | Ekombitié | 350 | | Akomnyada | 300 | | Akoumbeg-ssi | 100 | | Nseng-Elong | 250 | | Mbangassina | Bialanguena | 300 | | Bilomo | 200 | | Enangana | 200 | | Boura | 250 | | Biapongo | 200 |

|

|

3.2. Characterisation of Households

At Mbalmayo, 110 questionnaires were administered, that is 106 individual interviews and 4 focus groups. At Mbangassina, there were 101 questionnaires: 93 individual interviews and 8 focus groups (Table 2). | Table 2. Information on administered questionnaires |

| | Cocoa Region | Questionnaires for households | Focus group questions | TOTAL | | Mbangassina | 93 | 8 | 101 | | Mbalmayo | 106 | 4 | 110 | | TOTAL | 199 | 12 | 211 |

|

|

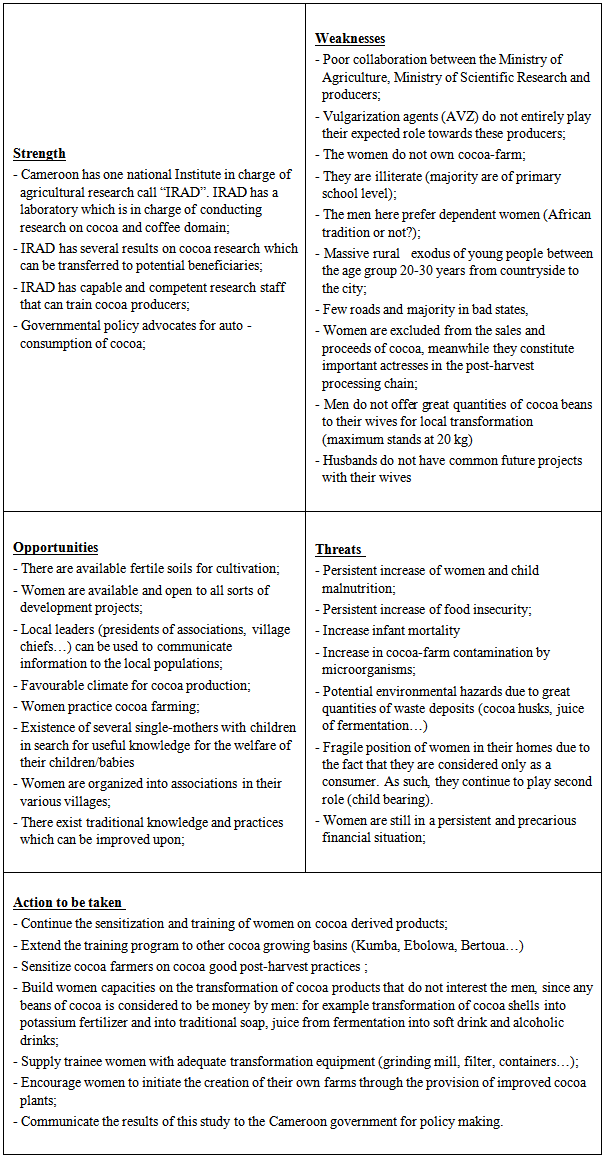

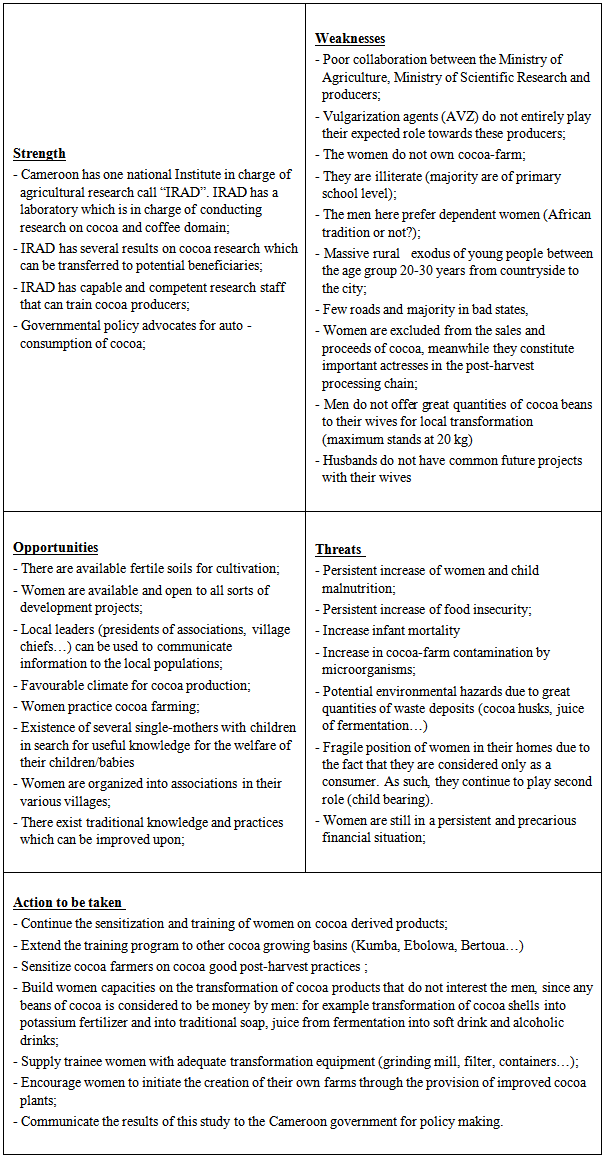

During the interview, some women did not wish to reveal their exact ages and others gave wrong ages. Nevertheless, nearly 70% of women appeared to have between 30 - 50 years. The women - targeted for this study were those of larger family sizes. The majority of households surveyed (nearly 70% of households) recorded between 5 to 10 persons at home. They were those with appropriate age that can or are able to use the knowledge that will be acquired in order to improve the livelihoods of their families. A majority of women (75%) leaf school at a primary.The food supplies of households differ with region. The diet of the Mbalmayo population is typically that of the forest area. The basic food supplied in this rural areas is made up of non-timber forest products (NTFPS) such as Djangsang, Andok (Bush-mango), Okok (eru), palm oil and wine, termites, fungi, honey, as well as banana, plantain, cassava, groundnuts etc. In the Mbangassina subdivision, food stuffs consumed are those of transitional zone, with bush-meat, cassava and maize much consumed in the form of fufu base on cassava and maize-flowers. Equally, there are also yams, groundnuts, melon-seeds and banana-plantain. Both in Mbalmayo or Mbangassina villages, soybeans are less consumed: less than 8% of women surveyed, actually consumed soybeans. The few households who consume do so either in the form of palp or as ingredient for vegetable cooking. Child feeding The women interviewed, reported that they were in-charge of feeding 354 children in the Mbalmayo subdivision and 311 children in the Mbangassina subdivision. In general, the children from these villages ate 2 meals per day: breakfast before going to school and lunch after returning from school. Figure 4 gives the composition of the breakfast taken by children in the 2 subdivisions. In the morning, these children take pap made from maize, donut, bread, left-over food of the previous day and at times milk. In these 2 study sites, more than 60% of the women held that they give left-over food as breakfast for the next day to their children: this represented approximately 248 children at Mbalmayo and 218 children at Mbangassina. Six percent of these women did not give anything for breakfast to their children in the morning. No child in the region of Mbangassina was given milk during breakfast. In the region of Mbalmayo, 3% of interviewed household gave milk to children before they leave for school. As such, only 11 children had the opportunity of taking milk in the morning.  | Figure 4. Composition of children’s breakfast |

After school, these children take their lunch made up of a typical dish of the transitional zones in Mbangassina or of a forest zone in Mbalmayo.For proper growth, a child need balanced diet which covers his basic nutritional needs (protein, carbohydrate, lipid and vitamin) as well as specific nutritional needs (iron, calcium and essential fatty acid). The milk and dairy products occupy an important place in the diet of children. The feeding and dietary habits of people in the villages which constitute this study did not allow them to have a good balanced diet, or to cover the specific nutritional needs of children. Thus, out of 665 children under the ages of 12 years concerned by this study, 466 can have problems of malnutrition.

3.3. Households Income and Sources of Their Income

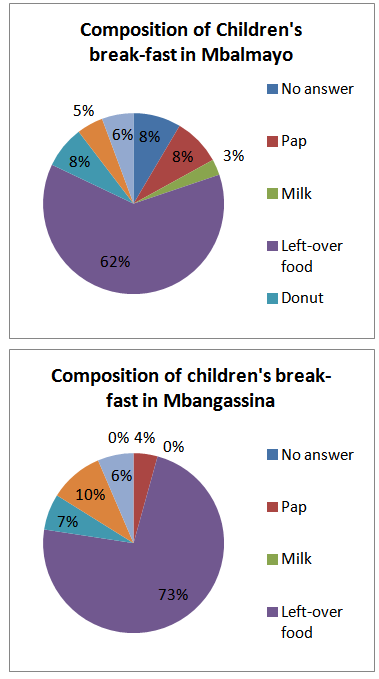

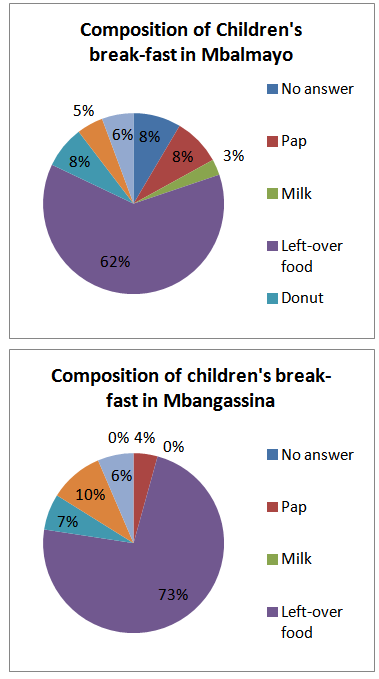

The main activity of women is agriculture, followed by the trading (Figure 5). In addition to these activities, women are also doing “pointage”, livestock breeders and civil services as secondary activity. The “pointage”, this is a new practice that is specific to the region of Mbangassina. It is a lucrative activity that entails working in the cocoa plantations and being paid in proportion to the quantity of cocoa-beans produced).  | Figure 5. Household revenue |

All the activities carried out by women (farming, trade, livestock etc.) enable them to annually generate some amount of money ranging from 200 Dollars to 2000 Dollars. The average annual income per women in the Mbalmayo subdivision stands at 600 Dollars as oppose to 1000 Dollars for those in Mbangassina.The importances of various lucrative activities that contribute to the household income are represented in the figure 5 below. The sale of other agricultural products contributed for about 46 %, closely followed by that of the cocoa 41 %, other earnings call “pointage” 11% and civil servants 1 %. Only the sale of cocoa and other agricultural products represents nearly 87% of the household annual income. The “pointage” income activities constitute an emerging and promising monetary source.

3.4. Dynamics of Women Associations

3.4.1. Mbangassina Subdivision Female Associations

Women in Mbangassina subdivision are more dynamic, open to development proposals, and are much involved in the associative life. The nature of the group varies: CIG, professional groups and tribal associations. Their group activities consist of working in the community farm: cocoa farming, cultivation of food crops (corn, cassava etc.). Community work is organized once a week. The main women associations that practice cocoa farming as group activity in the selected villages are: ASNEYACAM, QUI VIVRA VERRA, ESPOIR. Generally, each association has 05 cash accounts: savings account (for members’ savings), relief account (for mutual assistance in case of fortunate or unfortunate event). A scholarship account (to prepare children for each new school year), mutual interchangeable saving (done either by balloting or by official order), and a special counter for the income derived from group work. The revenues generated by the commercialization of cocoa and other crops are put into that special account of the association. The amount varies and may reach 1000 Dollars. At the end of each year, the women association may decide by mutual agreement on the usage of generated income. These funds are generally used for development investments: Construction of warehouses for the storage of dried cocoa-beans or other crops, purchase of equipment’s and collective investment in durable and real estate business (chairs for renting, cutlery, tents etc.). For example, in 2010, ASNEYACAM generated 2000 Dollars francs which enabled them to construct a warehouse. QUI VIVRA VERA generated 1000 Dollars which was used for the purchase of chairs for commercial letting.

3.4.2. Mbalmayo Subdivision Female Associations

The women of Mbalmayo subdivision are less associative. Unlike the women of Mbangassina, those of Mbalmayo do not perform farm work as a group activity; rather they practice agricultural activities on individual or family basis. Nevertheless, there exist a few associations of women who are only in-charge of managing money. These associations operate with 3 accounts: savings account, relief account and mutual interchangeable savings account.

4. Cocoa Post-harvest Practices

4.1. Harvesting

It is done by cutting the stalk with a cutlass. The traditional cutting-knife can also be used for the highly dented. This practice is common in all the cocoa production basins of Cameroon.

4.2. Extraction of Cocoa Beans

Cocoa pod is opening by a family, through mutual assistance between producers (rhythmical extraction), or in the form of services for benefit where payment are made on task work.Rhythmical Extraction is a mutually cultivated practice between the producers only, without the intervention of service payment. During the cocoa season, pod breaking is done by a group of farmers in the village gathered together, and this practice goes on in-turns. At the end of the working day, the recipient producer of the day, offers food and drinks to fellow farming colleagues. In order to work on significant quantities of cocoa pods, the harvesting can be spread over to several days, or even weeks. This leads to the degradation of the first harvested pods because they can stay-on for more than 07 days before being broken. During this time, the soil micro-organisms grow in the cocoa pods and can affect the quality of the final product. Table 3 below shows that nearly 64% of the interviewees acknowledged that they stuck pods for at least 07 days before breaking. Only 22% acknowledged breaking of cocoa pods within the regular period of 2 days at maximum after harvesting. These habits are relayed from father to son. Although this practice is valuable due to its social aspects, the rhythmical extraction poses a problem of the quality of cocoa due to the delay in the cocoa-breaking process. In order to obtain a quality product, rituals of this kind are to be improved upon.| Table 3. Duration of cocoa pod breaking |

| | Duration of cocoa-pod breaking (days) | Less than 3 days | 3-5 days | 7 days | More than 7 days | Total | | Mbangassina | 17 | 8 | 38 | 30 | 93 | | Mbalmayo | 26 | 21 | 38 | 21 | 106 | | TOTAL | 43 | 29 | 76 | 51 | 199 |

|

|

4.3. Fermentation

In these regions of study, the general tendency is that they do not ferment cocoa. About 62.3 per cent of women in the region of Mbalmayo testified that they do not ferment cocoa as opposed to 36.6 per cent in the region of Mbangassina. This phenomenon of non fermentation is much more observed in the village of Akomnyada, followed by Memiam. Only 5.6 per cent of women in Mbalmayo villages fermented cocoa beans during the required time scheduled which 4 to 6 days, against 12% of women in Mbangassina villages. Whatever the region, cocoa is not mixt during fermentation.

4.4. Cocoa Drying

Sun drying is the main method of drying in the different villages of Mbalmayo and Mbangassina. Cocoa is dried on tarpaulins, cemented surfaces, and traditional mats or on the tarred surfaces (asphalt) of the road. The drying on asphalt surfaces exclusively concerned the region of Mbalmayo, especially the villages of Ekombitie and Memiam regarding their proximity to tar road. The duration of drying varies with the area concern. Generally, the drying duration is much more important in the region of Mbalmayo and runs from 7 to 10 days. This duration reflects the fact that their cocoa is not fermented in advance. With the fermentation process, the mucilage drops and the drying becomes a little more rapid. Compared to Mbalmayo, post-harvest practices in Mbangassina region are allowed for improve cocoa quality.

5. Training of Women on Innovative Technologies

The training was realized in 2 phases: theoretical phase and practical phase.

5.1. Theoretical Training

The Theoretical phase was programmed to be interactive and was much enriching. It was during this phase that producers were enlightened on a part of the results collected during field survey, mainly on the post-harvest practices. The major concern was to explain the carelessness of farmers in their cocoa farming and processing practices: delayed in cocoa pod breaking, inadequate or no fermentation, handling mode, drying surfaces and duration, cocoa storage etc. This was an ideal occasion to empower women on cocoa post-harvesting and handling. The importance of grouped - sales of cocoa was equally emphasized.The theoretical training (figure 6) also permitted to explain to women innovative technologies used for the production of cocoa butter, cocoa powder and soy - chocolate drink. The technologies used were simple and practicable, using local materials that were available in rural areas.  | Figure 6. Theoretical training |

Theses technologies were defined par Mounjouenpou and al [15]. Cocoa Butter: Cocoa beans were placed in a locally made aluminum heating pot for roasting and were regularly being stirred for about 60 minutes under the temperature of about 100°C. Next, the roasted cocoa beans were introduced into a mortar and were lightly pounded in order to facilitate removal of the husk by winnowing. Thereafter, the beans were finely ground into paste with the aid of a mill. Water was added to the paste and then cooked for several hours. During boiling, cocoa butter emerged on the surface of the mixture, and was collected with the spoon. This liquid cocoa butter was washed using clean water and filtered using a clean tissue.Cocoa powder: After extracting the cocoa butter, cocoa paste was obtained by evaporating the water. Cocoa paste was dried to obtain cocoa cake. The dry cake was finely ground unto the desired grade. Cocoa powder obtained can be consumed as a hot drink with sugar or honey during breakfast or as cold chocolate drink.Soy-chocolate drink: To prepare 3 liters of this drink, soak 500 g of soya-beans in a saline solution for 24hrs. Whiten the soaked grains. In order to eliminate the taste of the beans, boil for 10 to 15 minutes at 80°C. Grind the soy-beans with little water. Measure 300g of soy-beans paste that will be poured into a large saucepan. Add 3 liters of water and 30% of cocoa paste (approximately 100g). Filter well with low mesh sieve. After grinding, the collected paste is boiled for 10 to 15 minutes. Flavor the drink by adding the lemongrass and later sweeten to give desired taste.

5.2. Practical Training

During the practical training (figure 7), women were grouped into experimentation unite of 10 persons each. The practical training was designed to teach women on how to produce: cocoa butter, cocoa powder and soy - chocolate drink.  | Figure 7. Practical training |

The table 4 gives the training statistics. Among the 199 cocoa women farmers interviewed, 185 effectively followed the training. Beside these women, 15 men equally benefited from the training. | Table 4. Training Statistics (Field interview & training statistics) |

| | Region | Participants interviewed | Participants trained | | Females | Males | Females | Men | | Mbangasina | 93 | 00 | 90 | 11 | | Mbalmayo | 106 | 00 | 95 | 4 | | Total | 199 | 00 | 185 | 15 |

|

|

The training was participatory and women showed a lot of enthusiasm and commitment. Women were gearing up to collaborate with the trainers (in fanning the fire, sifting the drink etc). The practical phase was a rich and interesting part. This was an occasion to demonstrate some comparisons to those that had already been trained (butter colour, bitterness of the butter and the cocoa powder etc.). Many women expressed surprises on things that could be derived from cocoa, and farmers adopted some resolutions to engage into taking better advantages of their cocoa. These cocoa producers tasted the different by-products of cocoa and gave positive impressions. The soy chocolate drink has been the flagship product of the women. Each of the women equally took home some sample products during the training with the aim of making their husbands have a taste of it. Each woman was also called upon to proceed to the rubbing or kneading of the muscles of the husband with cocoa butter.

5.3. CONACFAC NGO’s and Training

In order to better carry out this study, we collaborated with the National confederation of agro pastoral cooperatives and federation of Cameroon (CONACFAC). It’s is a cross-community group that covers all areas of cocoa production in Cameroon. CONACFAC is a field agent and serve as a facilitator between farmers and researchers. For any field activity (training and dissemination), this NGO’s is very important. Dissemination activities in any form have significant positive influences on both research and development [16]. It is through dissemination that new information from research can reach the target audience and to enhance their capacities to implement the ideas. The field days offer to communities the opportunities to observe and choose which technologies to adopt and for the University to engage with communities to identify capacity gaps and therefore, to respond by establishing research to address the communities’ needs [17].During training, the main concerns of women were:- The problem of accessibility to cocoaGenerally, men are the owners of the cocoa. The cocoa farm typically belongs to the husband (74 %), or it is a family asset (18 %), or even a simple rental (7 %). Only the widows can become owners of cocoa farms (< 1 %).Given that cocoa belongs to men, there is the problem of accessibility to cocoa beans. We must find ways and means for adhering men in the project. And thereby, they can give women large quantities of cocoa to transform. The proposed solution was to invite women to taste all processed products to their husbands. This is why processed product samples were distributed to women. Each woman was invited to make a cocoa butter massage treatment of her husband at home.- Market absorption of processed products One of the problems faced by rural women is to be able to sell the transformed products, since village markets are periodic and take place once every week. This market is thus insufficient to absorb the entire production of these women. Owing to this poor marketing program, these women were encouraged to resort to nearer cosmopolitan cities and sell portions of their products. - Low benefit from cocoa income The main problem of the majority of women, who are not owners of cocoa farms, is exclusion owing to the fact that they are not involved in the sale of cocoa beans. They work in the plantations and also actively participate in the process of cocoa beans extraction from pods, fermentation and cocoa drying. The sale of cocoa is at the exclusive control of the husband who does not render account of the sales to his wife. Women thus feel excluded from the proceeds since they cannot and may not benefit much from the income derived from the cocoa. When there is increased in the harvest, men take advantage to bring in another wife.Next is the inability in some women which limits them from discussing future projects with their husbands. The husband is a little discouraged due to the fact that the only concern of the woman is to look-after her family, and the husband is worried that the woman uses income from cocoa, not for the well being of the household, but to the benefit of her parental family.- The theft of harvested cocoaThe theft of harvested cocoa is a recurring phenomenon in these villages. This theft can cause serious crisis to the producer since almost all the cocoa producers live and depend on the income made from the farm. The stealing can occur in the farm, after the harvesting, or during the drying of the beans. Some producers find themselves loosing away of nearly half of their total production.

6. Areas of Investment for Future Strengthening Capacity for Sustainable Improvement of Women Livelihoods

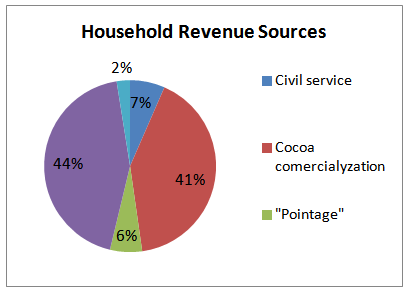

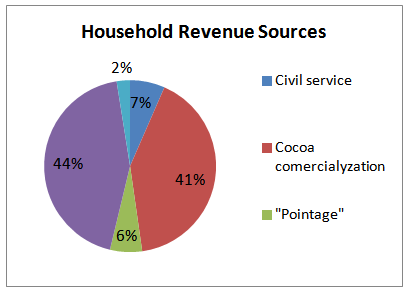

In order to better apprehend needs, expectations of Mbalmayo and Mbangassina women cocoa farmers for sustainable improvement of their livelihoods, SWOT analysis was done and the proposed recommendations were adopted in a plenary session. Responses from SWOT are shown in Table 5. Table 5. Results of SWOT Analyses for Future Strengthening Capacity for Sustainable improvement of women livelihoods

|

| |

|

We found that women cocoa farmers desire to be provided with training and extension services on agriculture. We also established the limited capacity of the field agent of the Minister in charge of Agriculture Department (AVZ) to assist and monitor producer. To address this gap, the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Agriculture Research should increase coverage and attain good depth of reach in the communities by using selected community members as resource persons. The community resource persons would be trained. In turn, the trained Community Resource Persons would train and work with communities to promote sustainable agriculture. In many development programs, the use of local communities as resource persons is a common phenomenon. Such persons are often selected by the communities. Therefore, they are trusted and have the potential to influence the community to willingly adopt innovations as has been the case in India [19] and Haiti [18]. When local persons are used to provide extension services, it reduces the risk of the information reaching only the local people with economic power who are often favored and perceived to readily adopt innovation and therefore provided with the extension services [20]. Therefore, local persons are community members who share similar socio-economic background and therefore, interact readily with many of the peers. The SWOT results and the responses showed that there is a need to provide capacity building of communities. This would create a critical mass of skilled trainers who would in turn train the rest of the community members.

7. Conclusions

This study is aimed at improving the capacities building of women cocoa producers in the Mbalmayo and Mbangassina subdivisions. Within these subdivisions, women were selected and were trained on the production of cocoa derived products: cocoa butter, cocoa powder and soy-chocolate drink. Cocoa butter was the most adopted product, followed by cocoa powder. The women chosen showed a lot of enthusiasm and interest. This study permitted to have 120 women cocoa farmers “trainers of trainers”, to learn about the sociology and the dynamics of women in the 2 regions. Similarly, it also allowed us to better understand cocoa post-harvest practices in these regions. After this training, cocoa farmers started consuming cocoa to ensure their food self-sufficiency, their feeding habit was improved. The food supply in these regions became more diversified and nutritional. The local consumption of cocoa and soya beans has substantially increased. Poverty among cocoa farming women has reduced since the surplus of the production can be sold. Furthermore, the leadership and economic capacities of the women within the households have been improved since they started contributing to the household charges and expenses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank the World Cocoa Foundation (WCF) for financing this study, CONACFAC NGO’s for their collaboration. My thanks also go to AWARD (African Women in Agricultural Research and Development), to my mentors Dr Woin Noé and Dr Achukwui Daniel and also to all colleagues who have contributed to the success of this study.

References

| [1] | Kreuger, R. A. 1994. A practical guide for applied research. Sage publications. California. |

| [2] | Massey, M. 2007. Sustainable development 20 years after Bruntland: Time for more patience and pragmatism, Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chartham House, UK. |

| [3] | ACP Science and Technology Programme (ACPSTP), 2012. Shifting from Outreach to Engagement: Transforming Universities' response to current development trends in agricultural research and training in Eastern, Central and Southern Africa.http://www.acp-st.eu/content/shifting-outreach-engagement-transforming-universities-response-current-development-trends-a (accessed July 3, 2012). |

| [4] | Direction des Eaux et Forets, Republic of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso). Secteur de Restauration de Sols de Ouahigouya. Department for International Development (DFID), 2011. A review on the effectiveness of capacity strengthening interventions and extent of the main capacity gaps in African Agricultural Research, UK. |

| [5] | Baker, A. 2005. Capacity building for sustainability: towards community development in coastal Scotland. Journal of Environmental Management 75: 11–19. |

| [6] | Lockheed, M. E. 1987. Farmers Education and Economic Performance. In: Economics of Education: Research Studies, Oxford: Perganonn, Psacharpolomes, G. (ed.). |

| [7] | Perrin, R. and D. Winklelmann, 1976. Impediments to Technical Progress on Small versus Large farms, American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 58(5):887-894. |

| [8] | Fletcher, S., 2003. Stakeholder representation and the democratic basis of coastal partnerships in the UK. Marine Policy 27, 229–240. |

| [9] | Beintema N., G. J. Stads, 2011. African agricultural R&D in the new millennium. Progress for some, challenges for many. Food Policy Report. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington. Agricultural Science and Technology Indicators, Rome. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.2499/9780896295438. |

| [10] | FAO, 2007. Programme national de sécurité alimentaire (PNSA) (2008 – 2015) |

| [11] | Curasi, C. F. 2001. A critical exploration of Face-to-Face interviewing vs. Computer-mediated interviewing. International Journal of Market Research 43: 361-75. |

| [12] | Fletcher, S., 2003. Stakeholder representation and the democratic basis of coastal partnerships in the UK. Marine Policy 27, 229–240. |

| [13] | Sanchez, P. A. 1995. Science in agroforestry. Agroforestry Systems 30: 5-55. |

| [14] | Glover, E. K. 2005. Tropical dryland rehabilitation: Case study on participatory forest management in Gedaref, Sudan. Doctor of Science Dissertation, Viikki Tropical Resources Institute (VITRI), Faculty of Agriculture & Forestry, University of Helsinki, Finland. |

| [15] | Pauline Mounjouenpou, Joseph Amang A Mbang, Bernard Guyot, Joseph-Pierre Guiraud, 2012. Traditional procedures of cocoa processing and occurrence of ochratoxin - A in the derived products. Journal of chemical and pharmaceutical research, 4(2):1332-1339. |

| [16] | Misra, D. and S. Kant, 2004. Production analysis of collaborative forest management using an example of joint forest management from Gujarat, India, Forest Policy and Economics, (6): 301-320. |

| [17] | African Conservation Tillage Network (ACT), 2009. A Training of Trainers (TOT) Curriculum on Conservation Agriculture/Animal Traction, Sudan Productive Capacity Recovery Programme (SPCRP)- South, Capacity Building Component OSRO/SUD/623/MUL. |

| [18] | Waddams, P. C. 2000. Better energy services, better energy sectors and links with the poor. In: Energy services for the world’s poor. Energy and Development Report, Washington, DC, USA, World Bank. p. 26-32. |

| [19] | Ghai, D. and J. M. Vivian (eds.), 1992. Grassroots Environmental Action: people participation in Sustainable development. Routledge, London and New York. |

| [20] | Fiszbein, A. 1997. Decentralization and Local Capacity: Some thoughts on a Controversial Relationship. Paper prepared for the Technical Consultation on Decentralization. Rome. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML