-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Advances in Life Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1387 e-ISSN: 2163-1395

2011; 1(2): 54-58

doi: 10.5923/j.als.20110102.10

Population Dynamics of Aphis Spiraecola Patch (Homoptera: Aphididae) on Medicinal Plant Cosmos Bipinnatus in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India

Shweta Dubey , Vinay Kumar Singh

Department of Zoology, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, 273009, U.P., India

Correspondence to: Vinay Kumar Singh , Department of Zoology, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, 273009, U.P., India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Seasonal history of green citrus aphid Aphis spiraecola Patch was studied in terai belt of eastern Uttar Pradesh, India during three consecutive years, 2006, 2007 and 2008. The green citrus aphid appears during the first week of November on Cosmos bipinnatus and attains a peak during third week of December during 2006-2007. Cause of increase in the population during first half of the November in the field seems due to healthy plants, favourable temperature (around 25ºC) and humidity (above 40% RH) and less predatorism/parasitism. Decrease in population after the peak population may be attributed to low humidity (less than 50% RH) and predatorism/parasitism along with maturity of the crop. Since its population attains single high peak during the crop season, its population can easily be regulated by using any eco-friendly management practice by enhancing the activities of predators (particularly ladybird beetles) as they come along with the aphid.

Keywords: Cosmos Bipinnatus, Green Citrus Aphid, Aphis Spiraecola, Predatorism, Parasitism, Seasonal History

Cite this paper: Shweta Dubey , Vinay Kumar Singh , "Population Dynamics of Aphis Spiraecola Patch (Homoptera: Aphididae) on Medicinal Plant Cosmos Bipinnatus in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India", Advances in Life Sciences, Vol. 1 No. 2, 2011, pp. 54-58. doi: 10.5923/j.als.20110102.10.

1. Introduction

- Knowledge of the seasonal history of an insect is very important because its biology is a result of the interaction between individuals of the species and their habitat (Southwood, 1978). It allows better understanding of the relationship between an insect and its environment, and provides basic information for interpreting spatial dynamics, designing efficient sampling programmes for population estimation and pest management, and the development of population models (Croft and Hoyt, 1983).Cosmos bipinnatus, commonly called the garden cosmos or Mexican aster, exotic for India, is a medium sized flowering herbaceous medicinal plant grown in gardens. This species is considered a half-hardy annual, although plants may re-appear via self-sowing for several years. The plant height varies from two to four feet. It has showy solitary red, white, pink or purple flowers that are 5-8 cm in diameter and up to 10 cm in some selections. The cultivated varieties appear in shades of pink and purple as well as white. Flowering is best in full sun, although partial shade is tolerated. The flowers of Cosmos attract birds and butterflies. Essential oil that consists mainly cosmene (20-40%) is extracted from the flowers of Cosmos bipinnatus and is of highly economic importance as it addresses emotional and mental aspects of illness and as antimalerial (Botsaries, 2007). Jang et al., (2008) describe Cosmos bipinnatus has also been used in a traditional herbal remedy for various diseases such as jaundice, intermittent fever, and splenomegaly. It has also a significant antioxidant activity and protective effect against oxidative DNA damage (Jang et al., 2008). In eastern Uttar Pradesh, the major ornamental or medicinal flower is Cosmos bipinnatus. Aphis spiraecola Patch is one of the major pests of cosmos in this area. However, very little is known about the seasonal history of A. spiraecola in terai belt of Uttar Pradesh. As such, the objective of the present study was to observe the seasonal history of A. spiraecola and to correlate it with biotic and abiotic factors.

2. Materials and Methods

- The study was undertaken during October to March of 2006, 2007 and 2008 at the field laboratory of the Department of Zoology, D.D.U. Gorakhpur University. Observations on the weekly build up of aphids were recorded. The crop was raised in the field by following all the recommended package of practice. Nursery of recommended variety Daydream was raised and transplanting was completed in the second week of September with plant to plant and row to row distance of 30x30 cm.Aphid population was determined by adopting the method of Church and Strickland (1954) modified by Kotwal (1981) again with some modification, i.e., weekly samples from 10 randomly selected plants were taken using random row, plant and leaf co-ordinates to determine aphid density per leaf. From each selected plant, three leaves, one each from upper, middle and lower part of the plant were examined for aphid population. When the population of aphid was low, the count was made directly on leaves in situ. However, when the aphid density was high, samples leaves were put in polythene bags separately. The aphid were anaesthetized by using benzene and removed on to a white paper with the help of brush and mean aphid population per leaf was worked out.

3. Results

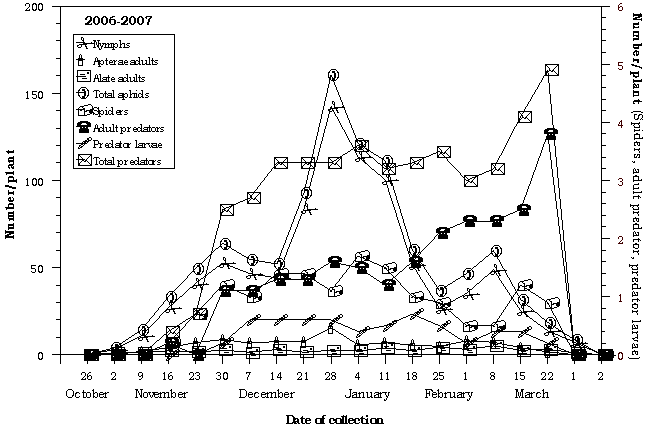

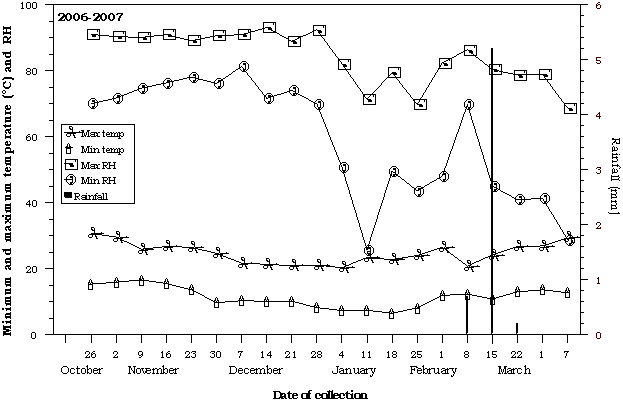

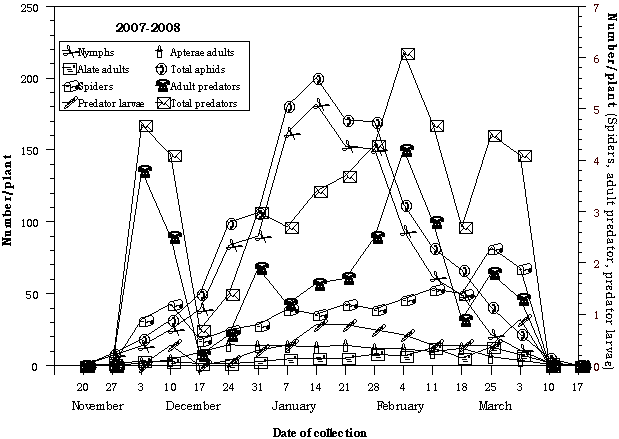

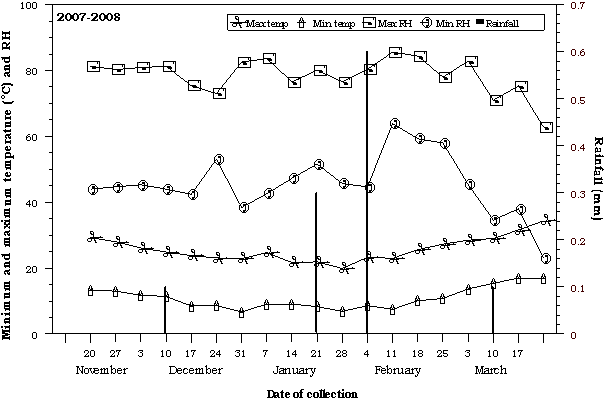

- Following natural enemies of Aphis spiraecola were recorded: spider (not identified), coccinellids (Cheilomenes sexmaculata, Coccinella septempunctata and Coccinella transversalis) both grubs and adults; and hover flies (Episyrphus balteatus, Ischiodon scutellaris) and green lacewing (Chrysoperla carnea carnea). The population of natural enemies was very poor up to 23 November, 2006, when less than 1.0 predator of any species was observed. They attain peaks only during first week of January (Figure 1). Because of their predatory activity and low humidity, the aphid population decreased thereafter. The degree of incidence of parasitoid (Binodoxys indicus) was very poor and only few mummies were discovered. During 2006-2007, the incidence of Aphis spiraecola was first recorded (4.0 aphids/plant: apterae– 0, alatae– 1, nymphs- 3) during first week of November (Figure-1) at a mean maximum temperature of 29.6°C, minimum temperature 15.9°C, maximum relative humidity 90.3 per cent and minimum relative humidity 71.7 per cent. Thereafter, the population of spiraea aphid builds up and reached a peak during last week of December, 2006 (160.6 aphids/plant: apterae– 15.5, alatae– 2.6, nymphs– 142.5) at corresponding mean maximum temperature of 21.1°C, minimum temperature 8.2°C, maximum relative humidity 92.4 per cent and minimum relative humidity 69.9 per cent. Thereafter, the minimum and maximum relative humidity decreased up to middle of the January, 2007 (Figure- 2) and the crop began to mature. These situations are unfavourable for aphid growth and hence its population decreased so that it remains only (36.8 aphids/plant: apterae – 4.8, alatae– 4.3, nymphs– 26.7) on January 25, 2007 at mean maximum temperature of 24.0°C, minimum temperature 8.1°C, maximum relative humidity 69.7 per cent and minimum relative humidity 43.6 per cent (Figure- 2).The rainfall was not observed up to first week of February. During the second and third week the rainfall was only 6.1 mm. Because of this humidity increased and the aphid attained one small peak during that period.During 2007-2008, the incidence of Aphis spiraecola was first recorded on 27 November, 2007, after three weeks of the incidence of the aphid on spiraea during 2006-2007 (7.2 aphids/plant: apterae – 0, alatae – 1.2, nymphs – 7.2) (Figure- 3) at a mean maximum temperature of 28.0°C, minimum temperature 13.0°C, maximum relative humidity 80.3 per cent and minimum relative humidity 44.7 per cent. The delay in appearance seems to be due to less humidity (about 10% in maximum RH and 30% in minimum RH; Table 13) than the previous year. Thereafter, the population of spiraea aphid builds up and reached a peak during first week of January, 2008 (200.3 aphids/plant: apterae– 13.2, alatae– 5.0, nymphs– 182.1) at corresponding mean maximum temperature of 21.7 °C, minimum temperature 9.1°C, maximum relative humidity 76.6 per cent and minimum relative humidity 47.3 per cent. During the following week about 0.3 mm rainfall was recorded. Simultaneously, the crop began to end and the population of predators (species as mentioned before) increased. These two factors seem to cause a decrease in the aphid population and it remains only (21.9 aphids/plant: apterae– 3.6, alatae– 7.6, nymphs– 10.7) on March 3, 2008 at mean maximum temperature of 28.5°C, minimum temperature 13.7°C, maximum relative humidity 71.0 per cent and minimum relative humidity 34.6 per cent (Figure- 3).The population of natural enemies was very poor up to 3 December, 2007, when less than 5.0 predators of any species were observed. They attain peaks only during first week of February (Figure- 3). Because of their predatory activity and low humidity, the aphid population decreased thereafter. During this year also, the extent of parasitism of the aphid was very poor and only few mummies having the parasitoid, Binodoxys indicus were observed. The rainfall was very poor during this year and less than 1.0 mm rainfall was observed during second week of December, third week of January, first week of February and second week of March, 2008. Because of this the maximum relative humidity remained around 70-80 % RH and minimum relative humidity remained around 40-50 % RH. The month of January, 2008 was observed for higher growth of the Aphis spiraecola when maximum and minimum temperature ranged between 22-25ºC and 7-9 ºC, respectively (Figure-4).

4. Discussion

- Aphids constitute a very significant group of pests of horticultural/medicinal crops. Cosmos bipinnatus is one of the most important ornamental/ medicinal crops and has been used as valuable ingredients of various medicines. It was found that population build up of Aphis spiraecola was negatively correlated to maximum (r=-0.775) and minimum temperature (r=-0.728, and positively correlated to maximum (0.122) and minimum (0.063) relative humidity. However, the significant (P< 0.05) positive correlation existed only between maximum and minimum temperature and population build up of the aphid, Aphis spiraecola. In association of relative humidity, the individual effect of minimum temperature was again significant; the two weather parameters influenced the aphid population to a great extent.

| Figure 1. Seasonal population build-up of Aphis spiraecola and its natural enemies on Cosmos bipinnatus during 2006-2007 |

| Figure 2. Seasonal variation in maximum and minimum temperature and humidity and rainfall during the occurrence of Aphis spiraecola on Cosmos bipinnatus during 2006-2007 |

| Figure 3. Seasonal population build-up of Aphis spiraecola and its natural enemies on Cosmos bipinnatus during 2007-2008 |

| Figure 4. Seasonal variation in maximum and minimum temperature and humidity and rainfall during the occurrence of Aphis spiraecola on Cosmos bipinnatus during 2007-2008 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML