-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Algorithms Research

p-ISSN: 2324-9978 e-ISSN: 2324-996X

2013; 2(2): 50-57

doi:10.5923/j.algorithms.20130202.03

Solving Ill Conditioned Linear Systems Using the Extended Iterative Refinement Algorithm: The Forward Error Bound

Abdramane Sermé

Department of Mathematics, The City University of New York, New York, NY, 10007, USA

Correspondence to: Abdramane Sermé, Department of Mathematics, The City University of New York, New York, NY, 10007, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper aims to provide a bound of the forward error of the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm used to find the solution to an ill conditioned linear system. We use the additive preconditioning for preconditioner of a smaller rank r and the Schur aggregation to reduce the computation of the solution to an ill conditioned linear system to the computation of the Schur aggregate S. We find S by computing W the solution of a matrix system using an extension of Wikinson iterative refinement algorithm. Some steps of the algorithm are computed error free and other steps are computed with errors that need to be evaluated to determine the accuracy of the algorithm. In this paper we will find the upper bound of the forward error of the algorithm and determine if its solution W can be considered accurate enough.

Keywords: Forward Error Analysis, Ill Conditioned Linear System, Sherman-Morrison-Woodbury (SMW) Formula, Preconditioning, Schur Aggregation, Iterative Refinement or Improvement, Algorithm, Singular Value Decomposition

Cite this paper: Abdramane Sermé, Solving Ill Conditioned Linear Systems Using the Extended Iterative Refinement Algorithm: The Forward Error Bound, Algorithms Research , Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 50-57. doi: 10.5923/j.algorithms.20130202.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

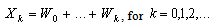

- We find the solution

of an ill conditioned linear system

of an ill conditioned linear system  by transforming it using the additive preconditioning and the Schur aggregation. We use the Sherman-Morrison-Woodbury (SMW) formula

by transforming it using the additive preconditioning and the Schur aggregation. We use the Sherman-Morrison-Woodbury (SMW) formula  where

where  is an invertible square matrix and

is an invertible square matrix and to get new linear systems. The challenge in solving these new linear systems of smaller sizes with well conditioned coefficients matrices

to get new linear systems. The challenge in solving these new linear systems of smaller sizes with well conditioned coefficients matrices  ,

,  and

and  is the computation of the Schur aggregate S. The technique of (extended) iterative refinement or improvement for computing the Schur aggregate[14] and its application for solving linear systems of equations has been studied in a number of papers[3, 15, 18]. Its variant that we used allows us to compute

is the computation of the Schur aggregate S. The technique of (extended) iterative refinement or improvement for computing the Schur aggregate[14] and its application for solving linear systems of equations has been studied in a number of papers[3, 15, 18]. Its variant that we used allows us to compute  with high precision. The high precision is achieved by minimizing the errors in the computation. The bound of the forward error will allow us to determine if the computed solution is an accurate one. This paper is divided into three sections. The first section covers the concept of rounding errors, floating-point summation, matrix norms and convergence. The second section is devoted to the additive preconditioning, the Schur aggregation and how the iterative refinement or improvement technique is used with the SMW formula to transform the original linear system

with high precision. The high precision is achieved by minimizing the errors in the computation. The bound of the forward error will allow us to determine if the computed solution is an accurate one. This paper is divided into three sections. The first section covers the concept of rounding errors, floating-point summation, matrix norms and convergence. The second section is devoted to the additive preconditioning, the Schur aggregation and how the iterative refinement or improvement technique is used with the SMW formula to transform the original linear system into better conditioned linear systems. The third section analyzes the forward error of the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm and provides a forward error bound.

into better conditioned linear systems. The third section analyzes the forward error of the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm and provides a forward error bound.2. Rounding Errors, Floating-point Summation, Matrix Norms and Convergence

2.1. Rounding Errors

- Definition 2.1.1 Let

be an approximation of the scalar x. The absolute error in

be an approximation of the scalar x. The absolute error in  approximating

approximating is the number

is the number  .Definition 2.1.2 Let

.Definition 2.1.2 Let  be an approximation of a scalar

be an approximation of a scalar  . The absolute and relative errors of this approximation are the numbers

. The absolute and relative errors of this approximation are the numbers and

and  , respectively. If

, respectively. If  is an approximation to

is an approximation to  with relative error

with relative error , then there is a number

, then there is a number  such that 1)

such that 1)  and 2)

and 2)  .Remark 2.1.1 The relative error

.Remark 2.1.1 The relative error is independent of scaling, that is the scaling

is independent of scaling, that is the scaling and

and leave

leave  unchanged.Theorem 2.1[6] Assume that

unchanged.Theorem 2.1[6] Assume that  approximates

approximates  with relative error

with relative error  < 1. Then

< 1. Then  is nonzero and

is nonzero and .Remark 2.1.2 If the relative error of

.Remark 2.1.2 If the relative error of  with respect to

with respect to is

is  , then

, then  and

and  agree to roughly

agree to roughly  correct significant digits. For binary system, if

correct significant digits. For binary system, if  and

and  have relative error of approximately

have relative error of approximately  , then

, then  and

and  agree to about

agree to about  bits.Definition 2.1.3 The componentwise relative error is defined as:

bits.Definition 2.1.3 The componentwise relative error is defined as:  for

for  and is widely used in the error analysis and perturbation theory.Remark 2.1.3 In numerical computation, one has three main sources of errors.1. Rounding errors, which are unavoidable consequences of working in finite precision arithmetic.2. Uncertainty in the input data, which is always a possibility when we are solving practical problems.3. Truncation errors, which are constituted and introduced by omitted terms.Rounding errors and Truncation errors are closely related to forward errors.Definition 2.1.4 Precision is the number of digits in the representation of a real number. It defines the accuracy with which the computations and in particular the basic arithmetic operations

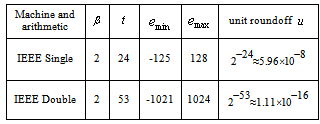

and is widely used in the error analysis and perturbation theory.Remark 2.1.3 In numerical computation, one has three main sources of errors.1. Rounding errors, which are unavoidable consequences of working in finite precision arithmetic.2. Uncertainty in the input data, which is always a possibility when we are solving practical problems.3. Truncation errors, which are constituted and introduced by omitted terms.Rounding errors and Truncation errors are closely related to forward errors.Definition 2.1.4 Precision is the number of digits in the representation of a real number. It defines the accuracy with which the computations and in particular the basic arithmetic operations  are performed. For floating point arithmetic, precision is measured by the unit roundoff or machine precision, which we denote u in single precision and ū in double precision. The values of the unit roundoff are given in Table 1.1 in Section 2.3.Remark 2.1.4 Accuracy refers to the absolute or relative error of an approximation.Definition 2.1.5 Let

are performed. For floating point arithmetic, precision is measured by the unit roundoff or machine precision, which we denote u in single precision and ū in double precision. The values of the unit roundoff are given in Table 1.1 in Section 2.3.Remark 2.1.4 Accuracy refers to the absolute or relative error of an approximation.Definition 2.1.5 Let  be an approximation of

be an approximation of  computed with a precision

computed with a precision  where

where is a real function of a real scalar variable.

is a real function of a real scalar variable.  is called the (absolute) backward error, whereas the absolute or relative errors of

is called the (absolute) backward error, whereas the absolute or relative errors of  are called forward errors.Definition 2.1.6 For an approximation

are called forward errors.Definition 2.1.6 For an approximation  to a solution of a linear system

to a solution of a linear system  with

with  and

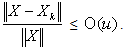

and  , the forward error is the ratio

, the forward error is the ratio  .The process of bounding the forward error of a computed solution in terms of

.The process of bounding the forward error of a computed solution in terms of  is called forward error analysis.

is called forward error analysis.  is the perturbation of

is the perturbation of  .Definition 2.1.7 An algorithm is called forward stable if it produces answers with forward errors of similar magnitude to those produced by backward stable method.Definition 2.1.8 A mixed forward-backward error is defined by the equation

.Definition 2.1.7 An algorithm is called forward stable if it produces answers with forward errors of similar magnitude to those produced by backward stable method.Definition 2.1.8 A mixed forward-backward error is defined by the equation  where

where  ,

,  with

with and

and  are small constants.Remark 2.1.5 This definition implies that the computed value ŷ differs little from the value

are small constants.Remark 2.1.5 This definition implies that the computed value ŷ differs little from the value  that would have been produced by an input

that would have been produced by an input  little different from the actual input

little different from the actual input  . Simpler,

. Simpler,  is almost the right answer for almost the right data.Definition 2.1.9 An algorithm is called numerically stable if it is stable in the mixed forward and backward error sense.Remark 2.1.6 A backward stability implies a forward stability but the converse is not true.Remark 2.1.7 One may use the following rule of thumb;Forward error

is almost the right answer for almost the right data.Definition 2.1.9 An algorithm is called numerically stable if it is stable in the mixed forward and backward error sense.Remark 2.1.6 A backward stability implies a forward stability but the converse is not true.Remark 2.1.7 One may use the following rule of thumb;Forward error  condition number

condition number backward error, with approximate equality possible. Therefore the computed solution to an ill conditioned problem can have a large forward error even if the computed solution has a small backward error. This error can be amplified by the condition number in the transition to forward error. This is one of our motivations for reducing the condition number of the matrix A using the additive preconditioning method.Definition 2.1.10 For a system of linear equations

backward error, with approximate equality possible. Therefore the computed solution to an ill conditioned problem can have a large forward error even if the computed solution has a small backward error. This error can be amplified by the condition number in the transition to forward error. This is one of our motivations for reducing the condition number of the matrix A using the additive preconditioning method.Definition 2.1.10 For a system of linear equations  ,

,  is called the relative residual. The relative residual gives us an indication on how closely

is called the relative residual. The relative residual gives us an indication on how closely  represents

represents  and is scale independent.

and is scale independent.2.2. Floating-point Number System

- Definition 2.2.1[6] A floating-point number system

is a subset of the real numbers whose elements have the form

is a subset of the real numbers whose elements have the form . The range of the nonzero floating-point numbers in

. The range of the nonzero floating-point numbers in is given by

is given by  . Any floating-point number

. Any floating-point number  can be written in the form

can be written in the form  where each digit

where each digit  satisfies

satisfies  and

and  for normalized numbers.

for normalized numbers.  is called the most significant digit and

is called the most significant digit and  the least significant digit.

the least significant digit.2.3. Error-free Floating-point Summation

- Here is a summation algorithm due to D.E. Knuth[7]. Algorithm 1. Error-free transformation of the sum of two floating point numbers

The algorithm transforms two input-floating point numbers

The algorithm transforms two input-floating point numbers  and

and  into two output floating-point numbers

into two output floating-point numbers  and

and  such that

such that  and

and  . The same solution is achieved using the Kahan-Babušhka’s[11] and Dekker’s[12] classical algorithm provided that

. The same solution is achieved using the Kahan-Babušhka’s[11] and Dekker’s[12] classical algorithm provided that  . It uses fewer ops but includes branches, which slows down the code optimization outputs.Definition 2.3.1[8] The unit roundoff error

. It uses fewer ops but includes branches, which slows down the code optimization outputs.Definition 2.3.1[8] The unit roundoff error  is the quantity

is the quantity  . We write

. We write  and

and  to denote the operations performed in single precision and in double precision, respectively.

to denote the operations performed in single precision and in double precision, respectively.

|

lying in

lying in  can be approximated by an element of

can be approximated by an element of  with a relative error no larger than

with a relative error no larger than  .Theorem 2.2 If

.Theorem 2.2 If lies in

lies in  then

then  with

with  <

<  Theorem 2.2 says that

Theorem 2.2 says that  is equal to

is equal to  multiplied by a factor very close to 1.Definition 2.3.2 From now on

multiplied by a factor very close to 1.Definition 2.3.2 From now on  , for an argument that is an arithmetic expression, denotes the computed value of that expression. op represents floating-point operation in

, for an argument that is an arithmetic expression, denotes the computed value of that expression. op represents floating-point operation in  .

.2.4. Matrix Norms

2.4.1. The Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)[3, 15]

- Definition 2.4.1 The compact singular value decomposition or SVD of an

matrix

matrix  of a rank

of a rank  is the decomposition:

is the decomposition:  where

where and

and  are unitary matrices, that is,

are unitary matrices, that is,  ,

, ,

, is a diagonal matrix,

is a diagonal matrix,  and

and  are m- and n-dimensional vectors, respectively, and

are m- and n-dimensional vectors, respectively, and  > 0.

> 0.  or

or  for

for  is the

is the  largest singular value of the matrix

largest singular value of the matrix  .Definition 2.4.2 The condition number,

.Definition 2.4.2 The condition number,  of a matrix

of a matrix of a rank

of a rank  is

is  . A matrix is said to be ill conditioned if its condition number is large, that is if

. A matrix is said to be ill conditioned if its condition number is large, that is if  , and is called well conditioned otherwise.Definition 2.4.3[6] The matrix 2-norm

, and is called well conditioned otherwise.Definition 2.4.3[6] The matrix 2-norm  =

=  =

=  , is also called the spectral norm.

, is also called the spectral norm.  denotes the largest singular value of the matrix

denotes the largest singular value of the matrix  .Remark 2.4.1 The matrix 2-norm satisfies the relation1.

.Remark 2.4.1 The matrix 2-norm satisfies the relation1.  where

where  ,

,  for

for  and

and .2.

.2.  .Lemma 2.3 For a vector norm

.Lemma 2.3 For a vector norm  , suppose that

, suppose that < 1 . Then

< 1 . Then  .

.2.5. Numerical Nullity

- Definition 2.5.1 The nullity of

,

,  , is the smallest integer

, is the smallest integer  for which a rank

for which a rank  APC

APC  can define a nonsingular A-modification

can define a nonsingular A-modification  . The nullity of

. The nullity of  , which is defined as the dimension of the null space can also be defined as the large integer r for which we have

, which is defined as the dimension of the null space can also be defined as the large integer r for which we have  or

or  , provided

, provided is a nonsingular matrix. In this case,

is a nonsingular matrix. In this case,  and

and  are the right and left null matrix bases for the matrix A.Definition 2.5.2 The numerical nullity of

are the right and left null matrix bases for the matrix A.Definition 2.5.2 The numerical nullity of is the number of its small singular values.

is the number of its small singular values.2.6. Convergence

- There is a natural way to extend the notion of limit from

to

to  .Definition 2.6.1 Let

.Definition 2.6.1 Let  be a sequence of vectors in

be a sequence of vectors in  and let

and let

. The sequence

. The sequence  converges componentwise to

converges componentwise to  and we write

and we write if

if  for

for  .Here is another way to define convergence in

.Here is another way to define convergence in  .Definition 2.6.2 Let

.Definition 2.6.2 Let  be a sequence of vectors in

be a sequence of vectors in  and let

and let

. The sequence

. The sequence  converges normwise to

converges normwise to  , that is

, that is if and only if

if and only if  There is no compelling reason to expect the two notions of convergence to be equivalent. In fact for infinite dimensional vector space, they are not.Theorem 2.4[6] Let

There is no compelling reason to expect the two notions of convergence to be equivalent. In fact for infinite dimensional vector space, they are not.Theorem 2.4[6] Let

and suppose that

and suppose that  .Then

.Then  is nonsingular and

is nonsingular and  (this sum is called Neumann sum). A sufficient condition for

(this sum is called Neumann sum). A sufficient condition for  is that

is that  < 1 in some consistent norm, in which case

< 1 in some consistent norm, in which case  .Corollary 2.5 If

.Corollary 2.5 If  , then

, then is nonnegative and

is nonnegative and  .Theorem 2.6[6] Let

.Theorem 2.6[6] Let be a matrix norm on

be a matrix norm on consistent with a vector norm (also denoted

consistent with a vector norm (also denoted

) and let a matrix

) and let a matrix

. Let

. Let  be a square matrix such that

be a square matrix such that  < 1. Then(i) the matrix

< 1. Then(i) the matrix  is nonsingular,(ii)

is nonsingular,(ii)  , and(iii)

, and(iii)  .The following corollary extends Theorem 2.6.Corollary 2.7[6] If

.The following corollary extends Theorem 2.6.Corollary 2.7[6] If  , then

, then  .Moreover,

.Moreover,  ,so that

,so that  .The corollary remains valid if all occurrences of

.The corollary remains valid if all occurrences of  are replaced by

are replaced by  .Theorem 2.8 [8, 17] Let

.Theorem 2.8 [8, 17] Let  denote a matrix norm and a consistent vector norm. If the matrix

denote a matrix norm and a consistent vector norm. If the matrix  is nonsingular and

is nonsingular and  and (i)

and (i)  , where

, where  is an approximated value of x, then(ii)

is an approximated value of x, then(ii)  .In addition if

.In addition if  < 1, then

< 1, then  is nonsingular and(iii)

is nonsingular and(iii)  .

.3. The Additive Preconditioning Method, the Schur Aggregation and the Extended Iterative Refinement or Improvement Algorithm

3.1. The Additive Preconditioning Method

- Definition 3.1.1 For a pair of matrices

of size

of size  and

and  of size

of size  , both having full rank r > 0, the matrix

, both having full rank r > 0, the matrix  of rank r is an additive preprocessor (APP) of rank r for any

of rank r is an additive preprocessor (APP) of rank r for any  matrix

matrix . The matrix

. The matrix is the A-modification. The matrices

is the A-modification. The matrices  and

and  are the generators of the APP, and the transition

are the generators of the APP, and the transition is an A-preprocessing of rank r for the matrix

is an A-preprocessing of rank r for the matrix  . An APP

. An APP  for a matrix A is an additive preconditioning (APC) and an A-preprocessing is an A-preconditioning if

for a matrix A is an additive preconditioning (APC) and an A-preprocessing is an A-preconditioning if  . An APP is an additive compressor (AC) and an A-preprocessing is an A-complementation if the matrix A is rank deficient, whereas the A-modification C has full rank. An APP

. An APP is an additive compressor (AC) and an A-preprocessing is an A-complementation if the matrix A is rank deficient, whereas the A-modification C has full rank. An APP  is unitary if the matrices

is unitary if the matrices  and

and  are unitary.Remark 3.1.1 Suppose

are unitary.Remark 3.1.1 Suppose  has rank r. Then[3, 18], we expect

has rank r. Then[3, 18], we expect  to be to the order of

to be to the order of  , therefore small if the additive preconditioner

, therefore small if the additive preconditioner  isi) randomii) well conditioned, andiii) properly scaled, that is

isi) randomii) well conditioned, andiii) properly scaled, that is  is not large and not small.Additive preconditioning consists in adding a matrix

is not large and not small.Additive preconditioning consists in adding a matrix  of a small rank to the input matrix

of a small rank to the input matrix  , to decrease its condition number. The A-modification is supposed to generate a well conditioned matrix

, to decrease its condition number. The A-modification is supposed to generate a well conditioned matrix . In practice, to compute the A-modification

. In practice, to compute the A-modification  error-free, we fill the generators

error-free, we fill the generators  and

and  with short binary numbers.

with short binary numbers.3.2. The Schur Aggregation

- The aggregation method consists of transforming an original linear system

into linear systems of smaller sizes with well conditioned coefficients matrices

into linear systems of smaller sizes with well conditioned coefficients matrices  ,

,  , and

, and  . The aggregation method is a well known technique[3, 14, 15, 18], but aggregation used here both decreases the size of the input matrix and improves its conditioning. One may remark that aggregation can be applied recursively until no ill conditioned matrix appears in the computation.Definition 3.2.1 The Schur aggregation is the process of reducing the linear system

. The aggregation method is a well known technique[3, 14, 15, 18], but aggregation used here both decreases the size of the input matrix and improves its conditioning. One may remark that aggregation can be applied recursively until no ill conditioned matrix appears in the computation.Definition 3.2.1 The Schur aggregation is the process of reducing the linear system  by using the SMW (Sherman-Morrison-Woodbury) formula

by using the SMW (Sherman-Morrison-Woodbury) formula . The matrix

. The matrix , which is the Schur complement (Gauss transform) of the block

, which is the Schur complement (Gauss transform) of the block in the block matrix

in the block matrix  , is called the Schur aggregate. The A-modification

, is called the Schur aggregate. The A-modification  and the Schur aggregate

and the Schur aggregate  are well conditioned, therefore the numerical problems in the inversion of the matrix A are confined to the computation of the Schur aggregate

are well conditioned, therefore the numerical problems in the inversion of the matrix A are confined to the computation of the Schur aggregate  .

.3.3. The Iterative Refinement or Improvement Algorithm

- Let

. Then, we apply the Sherman-Morrison -Woodbury (SMW) formula to the original linear system

. Then, we apply the Sherman-Morrison -Woodbury (SMW) formula to the original linear system  and transform it into better conditioned linear systems of small sizes, with well conditioned matrices

and transform it into better conditioned linear systems of small sizes, with well conditioned matrices  ,

, and

and  . We solve the original linear system

. We solve the original linear system  by post-multiplying

by post-multiplying  by the vector b. We consider the case where the matrices C and S are well conditioned, whereas the matrices

by the vector b. We consider the case where the matrices C and S are well conditioned, whereas the matrices  and

and  have small rank r, so that we can solve the above linear systems with the matrices

have small rank r, so that we can solve the above linear systems with the matrices  and

and  faster and more accurately than the system with the matrix

faster and more accurately than the system with the matrix  . In this case the original conditioning problems for a linear system

. In this case the original conditioning problems for a linear system  are restricted to the computation of the Schur aggregate

are restricted to the computation of the Schur aggregate  .To compute the Schur aggregate

.To compute the Schur aggregate with precision, we begin with computing

with precision, we begin with computing  using the iterative refinement or improvement algorithm. We prove that we can get very close to the solution W of the linear system

using the iterative refinement or improvement algorithm. We prove that we can get very close to the solution W of the linear system  . We closely approximate it by working with numbers rounded to the IEEE standard double precision and using error-free summation. All norms used in this section are the 2-norm. The iterative refinement or improvement algorithm is a technique for improving the computed approximate solution

. We closely approximate it by working with numbers rounded to the IEEE standard double precision and using error-free summation. All norms used in this section are the 2-norm. The iterative refinement or improvement algorithm is a technique for improving the computed approximate solution  of a linear system

of a linear system  . Iterative refinement or improvement for the Gaussian Elimination (GE) was used in the 1940s on desk calculators, but the first thorough analysis of the method was given by Wilkinson in 1963. The process consists of three steps ([6],[7],[15]).Algorithm 2. Basic iterative refinement or improvement algorithmInput: An

. Iterative refinement or improvement for the Gaussian Elimination (GE) was used in the 1940s on desk calculators, but the first thorough analysis of the method was given by Wilkinson in 1963. The process consists of three steps ([6],[7],[15]).Algorithm 2. Basic iterative refinement or improvement algorithmInput: An  matrix

matrix , a computed solution

, a computed solution  to

to  and a vector b.Output: A solution vector

and a vector b.Output: A solution vector  approximating

approximating  in

in  and an error bound

and an error bound  .Initialize:

.Initialize:  Computations: 1) Compute the residual

Computations: 1) Compute the residual  in double precision (

in double precision ( ) 2) Solve

) 2) Solve  in single precision (u) using the GEPP 3) Update

in single precision (u) using the GEPP 3) Update  in double precision (

in double precision ( )

) Repeat stages 1-3 until

Repeat stages 1-3 until  is accurate enough.Output

is accurate enough.Output  and an error bound.The iterative refinement or improvement algorithm can be rewritten as follows[6].

and an error bound.The iterative refinement or improvement algorithm can be rewritten as follows[6].  is the error in the computation of

is the error in the computation of  ,

,  is the error in the computation of

is the error in the computation of  and

and  , where

, where  is the perturbation to the matrix A.

is the perturbation to the matrix A.  is a computed solution of the linear system

is a computed solution of the linear system  .1)

.1)  2)

2)  3)

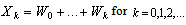

3)  Repeat stages 1-3.The algorithm yields a sequence of approximate solutions

Repeat stages 1-3.The algorithm yields a sequence of approximate solutions  which converges to

which converges to  .We use the extension of Wilkinson’s iterative refinement or improvement to compute the matrix

.We use the extension of Wilkinson’s iterative refinement or improvement to compute the matrix  with extended precision. In its classical form, above the algorithm is applied to a single system

with extended precision. In its classical form, above the algorithm is applied to a single system  , where

, where  and

and  are

are  vectors. We applied it to the matrix equation

vectors. We applied it to the matrix equation  , where the solution we are seeking is the matrix . In its classical version, also the refinement stops when the matrix

, where the solution we are seeking is the matrix . In its classical version, also the refinement stops when the matrix  is computed with at most double precision. In order to achieve the high precision in computing W, we apply a variant of the extended iterative refinement or improvement where the residuals dynamically decrease, which is a must for us. We represent the output value as the sum of matrices with fixed-precision numbers.

is computed with at most double precision. In order to achieve the high precision in computing W, we apply a variant of the extended iterative refinement or improvement where the residuals dynamically decrease, which is a must for us. We represent the output value as the sum of matrices with fixed-precision numbers.3.4. The Extended Iterative Refinement or Improvement

- Suppose

is an ill conditioned non-singular

is an ill conditioned non-singular  matrix with

matrix with  where

where  is the numerical nullity of the matrix

is the numerical nullity of the matrix  ,

,  is a random, well conditioned and properly scaled APC of rank r < n, and the well conditioned A-modification

is a random, well conditioned and properly scaled APC of rank r < n, and the well conditioned A-modification  . We use the matrices

. We use the matrices  and

and  whose entries can be rounded to a fixed (small) number of bits to control or avoid rounding errors in computing the matrix

whose entries can be rounded to a fixed (small) number of bits to control or avoid rounding errors in computing the matrix  .Surely, small norm perturbations of the generators

.Surely, small norm perturbations of the generators  and

and  , caused by truncation of their entrees, keep the matrix C well conditioned. We rewrite the iterative refinement or improvement algorithm to solve the linear system

, caused by truncation of their entrees, keep the matrix C well conditioned. We rewrite the iterative refinement or improvement algorithm to solve the linear system  with

with  and

and  as follows.Algorithm 3.

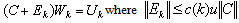

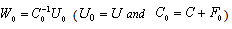

as follows.Algorithm 3. | (0.1) |

| (0.2) |

| (0.3) |

is computed by means of Gaussian Elimination with Partial Pivoting (hereafter GEPP), which is a backward stable process. It is corrupted by rounding errors of the computation of

is computed by means of Gaussian Elimination with Partial Pivoting (hereafter GEPP), which is a backward stable process. It is corrupted by rounding errors of the computation of  in (0.1), so that the computed matrix

in (0.1), so that the computed matrix  (computed in single precision arithmetic u) turns into

(computed in single precision arithmetic u) turns into  .

.  is the perturbation to the matrix C. We can also say equivalently that there exists an error matrix

is the perturbation to the matrix C. We can also say equivalently that there exists an error matrix  such that

such that  | (0.4) |

is an exact solution for the approximated problem.

is an exact solution for the approximated problem.  is a constant function of order

is a constant function of order  . Another source of error is the computation in (0.2) which, done using double precision arithmetic

. Another source of error is the computation in (0.2) which, done using double precision arithmetic  , turns numerically into

, turns numerically into  | (0.5) |

| (0.6) |

| (0.7) |

, derived from the ill conditioned linear system

, derived from the ill conditioned linear system  , by applying the following extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm.

, by applying the following extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm.

| (0.8) |

| (0.9) |

Let

Let  .Theorem 3.1[1]

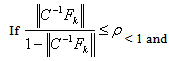

.Theorem 3.1[1] | (0.10) |

| (0.11) |

In other words,

In other words,  is bounded by

is bounded by  for a certain integer k. Proposition 3.2 Let

for a certain integer k. Proposition 3.2 Let  be nonsingular and let consider the linear system

be nonsingular and let consider the linear system . If

. If  <ρ < 1, then the matrix

<ρ < 1, then the matrix  is nonsingular and

is nonsingular and where

where | (0.12) |

.

.4. Forward Error Analysis

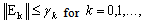

- Our forward error analysis of the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm results with the following proposition.Proposition 4.1 (Forward error bound) Let

be a linear system derived from an ill conditioned linear system

be a linear system derived from an ill conditioned linear system  where

where  is

is  ,

, is

is  both with full rank r> 0, and

both with full rank r> 0, and  is a well conditioned A-modification. If

is a well conditioned A-modification. If  is solved using the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm, Algorithm (4.) then for sufficiently large

is solved using the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm, Algorithm (4.) then for sufficiently large  the forward error

the forward error  is bounded by

is bounded by  . That is

. That is  where

where  and

and are constant functions of order k. Furthermore we have

are constant functions of order k. Furthermore we have The forward error is bounded by a constant in the order of u which is an important result.Proof: We obtain from equation (0.4),

The forward error is bounded by a constant in the order of u which is an important result.Proof: We obtain from equation (0.4), . Since

. Since  , we get

, we get  by using (0.4).

by using (0.4).  by using (0.5),

by using (0.5), by using (0.12) in Proposition (3.2),

by using (0.12) in Proposition (3.2), ,

, by using (0.2). We have,

by using (0.2). We have,  ,

, ,

, , so that

, so that ,

, Consequently

Consequently

, so

, so .Without loss of generality we can assume that

.Without loss of generality we can assume that  .Recall that

.Recall that  < 1, and take the norm on both sides, to get

< 1, and take the norm on both sides, to get  .Recalling (0.6) and (0.7), we deduce that

.Recalling (0.6) and (0.7), we deduce that  We recall the following inequalities (0.12),

We recall the following inequalities (0.12),  < 1. From (0.7)

< 1. From (0.7)  , Therefore

, Therefore  ,

,

. So

. So  .We recall (0.6)

.We recall (0.6)  . We also have

. We also have

where

where and

and .

.  and

and  are constant functions of order

are constant functions of order  .

. < 1 and

< 1 and  < 1 since C is well conditioned, we deduce that

< 1 since C is well conditioned, we deduce that  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  .We also recall that

.We also recall that  ,so that

,so that  and

and  …

…

. Therefore,

. Therefore,

.Therefore for sufficiently largek, we have

.Therefore for sufficiently largek, we have . Moreover,

. Moreover, . So,

. So,  where

where  and

and  are constant functions of order

are constant functions of order  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  .

.5. Conclusions

- We use the concepts of additive preconditioning and Schur aggregation along with the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm to reduce the computation of

to the computation of the Schur aggregate

to the computation of the Schur aggregate  . We solve the linear system

. We solve the linear system  with high precision using the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm. We proved in our forward error analysis that the forward error

with high precision using the extended iterative refinement or improvement algorithm. We proved in our forward error analysis that the forward error  is bounded by

is bounded by  . The forward error can further be bounded by

. The forward error can further be bounded by  , a constant of order u. These results are in line with Higham’s results ([6], page 234, Theorem 11.1) and constitute another way to prove the convergence of the extended iterative refinement or improvement to a more accurate solution

, a constant of order u. These results are in line with Higham’s results ([6], page 234, Theorem 11.1) and constitute another way to prove the convergence of the extended iterative refinement or improvement to a more accurate solution  .

.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank Professor Victor Pan, Distinguished professor of The City University of New York for his support and advice. The author would also like to thank his wife Lisa C. Serme for her support.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML