-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Systems Science

p-ISSN: 2332-8452 e-ISSN: 2332-8460

2017; 5(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.ajss.20170501.01

Failures of Systems Thinking in U. S. Foreign Policy

Jamie P. Monat, Thomas F. Gannon

Systems Engineering Program, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA

Correspondence to: Jamie P. Monat, Systems Engineering Program, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Systems Thinking can be used to analyze and solve complex real-world problems that cannot be solved using short-sighted linear thinking. It can also help to understand complex international issues, such as the rise of terrorism and support for anti-American activities around the world; and to understand the illogical behaviors of organizations such as ISIS. In this paper, we apply the Systems Thinking methodology described by Monat and Gannon (2017) to analyze America’s foreign policy approach over the past 40 years. We conclude that the United States’ foreign policy has failed to use Systems Thinking in dealing with international issues. Instead of a cohesive strategy, the foreign policy has been one of short-sighted tactics, often with dire consequences. Examples include the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, the 2011 invasion of Libya, the arming of the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan, and even the rise of ISIS. Fundamental System Thinking principles that have been absent in addressing international issues include failure to recognize unintended consequences, failure to recognize and understand feedback loops, fixes that fail, poor root-cause analysis, and seeking the wrong goal. These failures are not exclusive to any one administration, but seem to be part of a pattern whose roots are embedded in the cultures of the U. S. State Department, the military, and the intelligence community.

Keywords: Systems Thinking, Foreign Policy, Unintended Consequences, ISIS, Terrorism

Cite this paper: Jamie P. Monat, Thomas F. Gannon, Failures of Systems Thinking in U. S. Foreign Policy, American Journal of Systems Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.ajss.20170501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- After WW II, U. S. foreign policy seemed to embody a coherent strategy for dealing with the rest of the world. Characterized by liberation of invaded countries, economic development, and an interest in world peace, the U. S. philosophy was not tainted by ulterior motives such as the need for oil or the desire to act as the world’s policeman. This changed gradually over the ensuing years to the point where U. S. actions have often done more harm than good. The 2003-2011 Iraq war, for example, has been cited as “a reason for the diffusion of jihad ideology” (Mazzetti, 2006; National Intelligence Council, 2006). This damage is typically the result of short-sighted linear thinking, in which feedback loops are either not identified or ignored, the systemic root cause of issues is not discovered, and unintended consequences predominate. Much of this damage could be avoided (and international relations set on an appropriate course) through the application of Systems Thinking to U. S. foreign policy.

2. What is Systems Thinking?

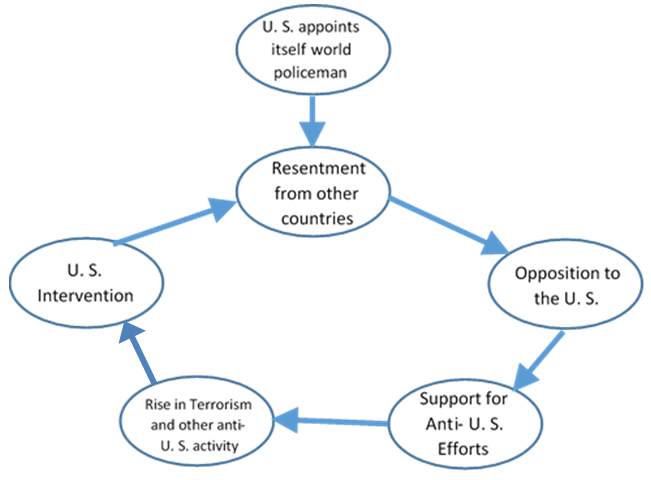

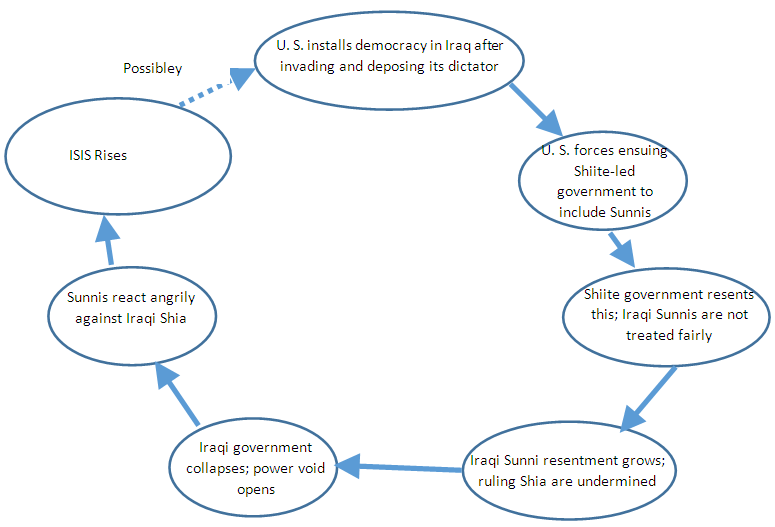

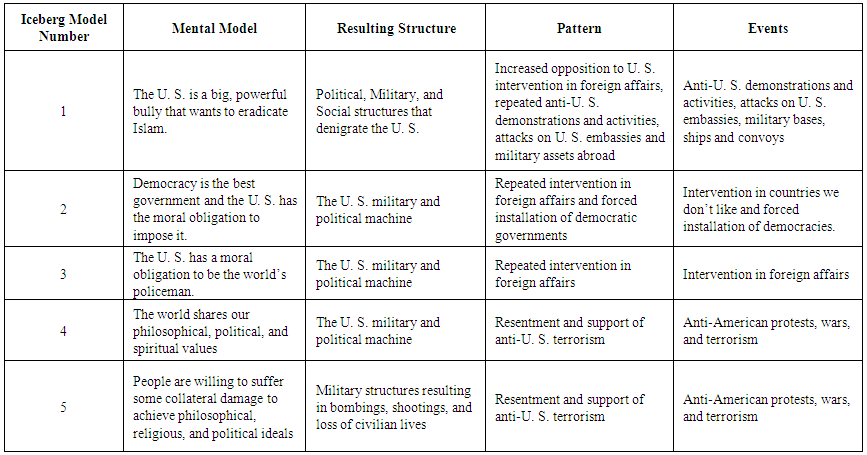

- Systems Thinking is a perspective, a language, and a set of tools that can be used to address complex political and socio-economic issues. Systems Thinking is the opposite of linear thinking. It is a holistic approach to analysis that focuses on the way a system's constituent parts interrelate, and how systems work over time and within the context of larger systems. Systems Thinking allows one to recognize that repeated events or patterns are derived from systemic structures which are derived from mental models. It also helps one recognize that behaviors are derived from structure. Systems Thinking focuses on relationships rather than components, considers the short and long term consequences of actions, recognizes the emergence of unintended consequences, and recognizes the principles of self-organization. Systems Thinking tools include system archetypes, causal loops with feedback and delays, and systemic root cause analysis. For a comprehensive summary of systems thinking terms, tools and techniques, see Monat and Gannon (2015).System archetypes are patterns of behavior that are repeated in a variety of situations and organizations. They include “accidental advisories”, “fixes that fail” and “seeking the wrong goal.” The “accidental adversaries” archetype can occur when two or more entities initially either collaborate or exist harmoniously. Eventually one entity does something that the other entity perceives to be damaging, so that entity reacts. In turn, the other entity reacts, and the pattern of behavior results in a death spiral. The U. S. and North Korea are an example. The U. S. has no real interest in North Korea (either positive or negative) but views its missile development and nuclear program as a threat. It reacts by conducting military exercises with South Korea in the Yellow Sea and Sea of Japan. North Korea views these (along with the U. S.’s anti-communist philosophy and friendship with South Korea) as threats, and so ramps up its military programs; hence the death spiral. In many cases, the problem is that the actions of a partner are viewed as adversarial, when the partner is only guilty of pursuing a self-interest without taking into account the effects of those actions on the other partner. Local thinking, mistrust, and poor communication contribute to this archetype.The “fixes that fail” archetype is another common behavioral pattern which identifies a problem and attempts to fix it, only to find out that the “fix” causes another problem. This archetype typically occurs when trying to “fix” problems in political, organizational or social systems that have very strong stabilizing or balancing feedback loops. Examples include the prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s and the overthrow of Sadam Hussein, which unleased ethnic resentment between Iraqi Sunnis and Shiites based on competition for power, and ultimately gave rise to ISIS as an unintended consequence. Another example is the decision by the State Department to arm Sunni rebels against Assad in Syria, only to provide ISIS with the opportunity to seize billions of dollars in U. S. military equipment after capturing Mozul as another unintended consequence. The “seeking the wrong goal” archetype arises when one establishes a goal which may be easier to accomplish or measure, but does not represent the desired end result. One example is the goal of U. S. foreign policy to act as the world’s policeman to achieve world peace, which has resulted in the rise of terrorism, resentment from other countries, and support for anti-American activities around the world. Another example is the military’s objective of incapacitating terrorists. This addresses a symptom, not the problem itself, which is poverty, oppression, corruption, and despair. We may eventually disarm or kill all ISIS, Al Qaeda, and Taliban terrorists currently active in the Middle East. But until we address the root causes that give rise to terrorism, new terrorist groups will rise under different names.Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) show how various system components inter-relate and interact with each other. They are useful in illustrating feedback processes, which are present in most systems and often ignored in linear thinking analyses. Examples include stabilizing feedback loops, such as a home thermostat, and reinforcing feedback loops, such as interest compounding in a bank account. Another example of a reinforcing feedback loop is the continued intervention by the U. S. in local conflicts, which reinforces the resentment of other countries toward the U. S., gives rise to increased anti-American activity, and results in more U. S. intervention as depicted in the Causal Loop Diagram of Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Causal Loop Diagram Showing the Impact of the U. S. Acting as the World’s Policeman |

3. Methodology and Approach

- Monat and Gannon (2017) present a good methodology for applying Systems Thinking to solving real-world problems. They argue that “Solving a problem using Systems Thinking begins with stating the problem or issue, defining the system, applying appropriate tools, and drawing conclusions. Those tools must be selected and the optimal sequence of application must be customized for each specific situation.” Their approach is summarized here:Step 1. Develop and articulate a problem statement.Step 2. Identify and delimit the system.Step 3. Identify the Events and Patterns.Step 4. Discover the Structures.Step 5. Discover the Mental Models.Step 6. Identify and Address Archetypes.Step 7. Model (if appropriate).Step 8. Determine the systemic root cause (s).Step 9. Make recommendations.Step 10. Assess Improvement.They note that for a specific problem not all steps need be followed (Step 7 -- Dynamic Modeling, for example, may not be useful in certain situations) and that the sequence of steps may be changed as appropriate.Step 1: Problem Statement: The U. S. foreign policy approach and actions over the past 40 years have often done more harm than good, resulting in an increase in terrorism, loss of lives, wasted resources, economic and humanitarian hardship, and loss of respect for America in the world.Step 2: System Definition and Boundaries: The system to be analyzed is the U. S. State Department, military, and intelligence community’s foreign policy culture, philosophy, approach, and actions with respect to terrorism originating in the Middle East and Northern Africa. The Middle Eastern/Northern Africa people, governments, cultures, and attitudes are a part of this system.In the following examples, we apply steps 3-6 and 8-9 of the methodology described above and demonstrate how the lack of or poor application of fundamental Systems Thinking principles can result in short-sighted tactics with dire consequences in addressing international issues. Step 7 was deemed inappropriate for this analysis and step 10 remains for future consideration.

4. Examples

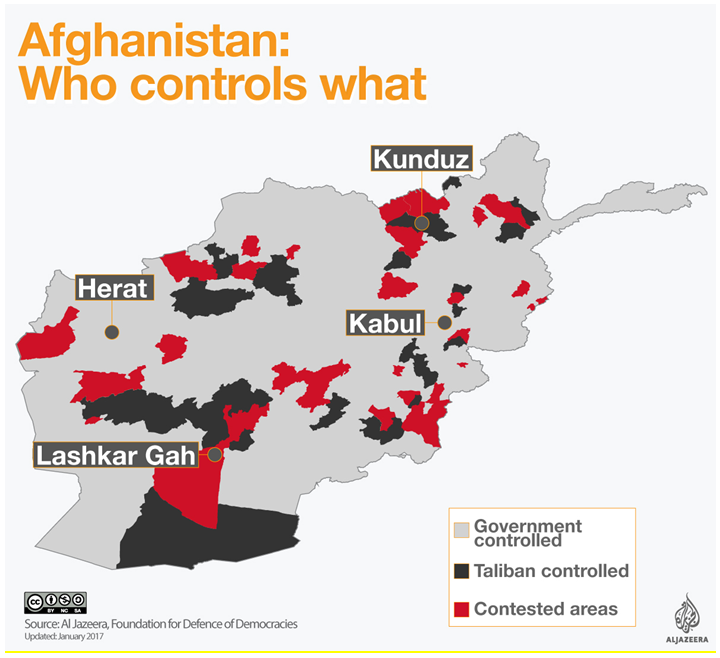

- Arming of Jihadi Rebels in Afghanistan (1979-89)The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to support the Communist regime of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan, which was losing popular support to anti-Soviet Islamic tribal factions outside of Kabul (U. S. Department of State, 2017). By the time of the invasion, the U. S. (under President Jimmy Carter) had already begun supplying the Mujahedeen, or Afghan Muslim freedom fighters, with non-lethal aid, to bolster their battle against communism and Soviet dominance. The Soviets were hoping for a quick, decisive victory; instead the war would drag on for 10 years and cost billions of dollars and millions of lives.The U. S. saw the war as an opportunity to defeat (or at least restrict) Communism and the Soviet Union (vestiges of the debunked Domino Theory); radical Islamic terrorism was not a concern. The Mujahadeen were viewed as freedom fighters, and during the Reagan administration (1980-1988) the U. S. supported the Mujahadeen with billions of dollars, weapons, and training (which included the use of car bombs, assassinations, and terrorism (Gane-McCalla, 2011)). (The movie Charlie Wilson’s War glorifies the efforts of Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson to secure weapons for the oppressed Afghan rebels.) The support of the rebels was easy to rationalize with a flawed mental model: they were a faithful religious faction fighting a godless Soviet invader and thus supported traditional American values. Zbigniew Brzezinski told the Mujahadeen, “We know of their deep belief in God, and we are confident their struggle will succeed. That land over there is yours, you’ll go back to it one day because your fight will prevail, and you’ll have your homes and your mosques back again. Because your cause is right and God is on your side.” Eventually, they did prevail, and the Soviets were driven out of Afghanistan having failed to unite the country under Soviet rule.Several unintended consequences developed as a result of U. S. actions. During the 10-year war, several Mujahadeen factions grew in both number and power: the Taliban, Al Qaeda, and the Muslim Brotherhood. Armed by the U. S., the forerunners of these factions were initially allied with America. But as the jihad strengthened in the late 1980s, so did anti-American sentiment. Several jihadist leaders such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar (who had received $600 million from the U.S) and Abdul Sayyaf became more openly hostile toward the U. S. and initiated a propaganda war against not only the USSR, but also the U. S. The rising anti-U. S. sentiment was largely ignored by the second Regan administration as well as by the first Bush administration, neither of which chose to study or understand the local culture and systemic root causes of the anti-American sentiment (Coll, 2004). One of the Mujahadeen was a young, wealthy Saudi named Osama Bin Laden. British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook said, “Bin Laden was, though, a product of a monumental miscalculation by western security agencies. Throughout the 80s he was armed by the CIA and funded by the Saudis to wage jihad against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan” (Gane-McCalla, 2011).Eventually Bin Laden, Al Qaeda, and the Taliban became among the most notorious terrorist organizations on earth. And the U. S. had funded, armed, and trained them.Systems Thinking Gaffs: the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan• Failure to understand Systemic Root Causes: ○ The U. S. had learned about the difficulties of waging an ideological war thousands of miles from home from Vietnam; however it still did not appreciate the need to understand local politics, values, and psychological needs. As Steve Coll says, “The idea that Afghanistan was a messy place filled with complexity and ethnicity and tribal structures and all of the rest of what we now understand about Afghanistan was it was generally not part of American public discourse.”○ The Mujahedeen didn’t hate the USSR because they were communists; they hated them for the same reason they would come to hate the U. S.: imperialism and a wide gap in values. Failure to understand basic Mujahadeen values.• Erroneous Mental Models: ○ The enemy of my enemy is not necessarily my friend; and in retrospect a U. S. alliance with the USSR against the Mujahedeen might have served the world better.○ Just because a group believes in God and doesn’t like Soviet influence doesn’t mean that the bases for those beliefs are consistent with ours.• Unintended consequences:○ Growth of the Taliban, Al Qaeda, and the Muslim Brotherhood○ Growth of Osama Bin Laden’s power and influenceAl Shabaab in Somalia (2000-present)After the overthrow of dictator Siad Barre in 1991, Somalia was a violent, chaotic place with severe food shortages. Local warlords and militias brutalized rival factions and killed and tortured ruthlessly (Adow, 2008, Hogg, 2008, Munger, 2015). These militias often aligned with local “courts” which maintained their versions of Islamic Sharia law. In 2000, several of the local courts united to form the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) in Mogadishu. The ICU provided health services, education, and security as well as law, and the areas they controlled became safer than warlord-controlled regions; their popularity grew steadily in the early 2000s (James, 1995; Stanford, 2016b).But the U. S. viewed the ICU as an extremist Islamic group and feared that Somalia was becoming a haven for terrorists. Acting as the world’s policeman, in 2006 the U.S. supported the development of the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism (ARPCT), an unlikely coalition of unpopular warlords who were not affiliated with the ICU (Bureau of Investigative Journalism, 2012). This generated substantial local resentment and instead of helping defeat the ICU, resulted in greater support for it; a major unintended consequence. Riding this wave of popular support, Al Shabaab, the ICUs military wing, defeated ARPCT in 2006 and as a result gained power and influence. Meanwhile, Somalia’s “official” government, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was attempting to consolidate power outside Mogadishu in opposition to the ICU. With U. S. and U. N. support, Ethiopia entered into the fray on the side of the TFG. In late 2006 the U. S.-supported Ethiopian army defeated the ICU and took control of Somalia. An unintended consequence of this action was the separation of Al Shabaab from the ICU as an independent military organization that became identified as the resistance against the occupying Ethiopian forces. Al Shabaab developed an alliance with Al Qaeda in a broad jihadist movement that embraced terrorist attacks on civilians (Associated Press/CBS, 2012).There have been various changes in Al Shabaab leadership and alliances since 2006, and the organization lost some local support when Ethiopian troops withdrew from Somalia in 2008. However, Al Shabaab continues as a radical Islamic terrorist group and has been responsible for several suicide bombings in Uganda and Kenya and for attacks on local relief workers in Somalia (Stanford, 2016a). Somalia is more stable now than in 2000-2012; however the war between the government and Al Shabaab continues in 2017 and Al Qaeda has been strengthened as a result of its association with Al Shabaab (another unintended consequence).Systems Thinking Gaffs: Al Shabaab in Somalia• Unintended consequences: ○ The rise of local support of the ICU was a result of U. S. support of ARPCT, and contributed to the resulting rise of Al Shabaab.○ The U. S. support of the Ethiopian invasion strengthened both Al Shabaab and Al Qaeda.• Feedback loops: ○ The invasion and defeat of the ICU caused Al Shabaab to separate.○ The “U. S. as the world’s policeman” mental model generated local anti-U. S. sentiment. The U. S. was viewed as an invader.Afghanistan (2001-present) Afghanistan is a complex country, characterized geographically by rugged mountains, caves, and a harsh climate. This makes it especially beneficial for the locals who used the terrain to hide and organize during conflicts. And there have been many conflicts among the various tribal factions and invaders, over hundreds of years. The country is approximately 42% Pashtun (a tribal people who strongly identify with clans and follow “Pashtunwali,” a self-governing tribal system) and 27% Tajik (a Persian-speaking group of Iranian descent who are not organized by tribes (Afghanistan Language and Culture Program (ALCP), 2017; Asian Wall Street Journal, 2011; Gouttierre and Baker, 2003.)) Administratively, there has never been a strong centralized government; instead rule is maintained by local Pashtun commanders in many areas, especially the northeast. Afghanistan is one of the poorest, most corrupt countries in the world (Chapman, 2016). The poppy-based drug trade has yielded profits ranging from 13-60% of the country’s GDP, 23% of which is consumed by bribery (McCoy, 2016; UNODC, 2010). Drug trafficking provides substantial funding for the Taliban.After the Vietnam War disaster and the similar Soviet debacle in Afghanistan, one would think that the U. S. would have learned its lesson: that ideological wars fought thousands of miles away without an understanding of local factions, cultures, values, and psychological needs lead to disaster; that the enemies of our enemies are not necessarily our friends; and that serving as the world’s policeman is not viewed favorably. Such was not the case, and those erroneous mental models persist.Following the September 11, 2001 attacks, the. U. S invaded Afghanistan with the objectives of driving out the Taliban, dismantling Al Qaeda, and capturing or killing Osama Bin Laden (BBC, 2017; Witte, 2017). By late 2001, the Taliban had been driven from power, American ally Hamid Karzai had been installed as the Afghan leader (later president), Bin Laden was on the run, and the U. S. led victory seemed clear. But in a series of unintended consequences, most Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters had escaped to neighboring Pakistan or to the rugged, mountainous regions of Afghanistan, and Taliban leader Mohammed Omar regrouped and subsequently led an insurgency against the official Afghan government and U. S. allies. With the Taliban driven out, the Pashtun regional warlords regained local control, resulting in a chaotic mix of small tribal fiefdoms. And what seemed like a quick, decisive victory turned into a drawn-out, 16 year war (the longest in U. S. history) with a concomitant loss of 2,300 American lives at a cost of more than $800 billion (Chapman, 2016). Our use of superior military strength and faith in the righteousness of our cause failed to consider the inevitable feedback loops and again paved the way for disaster.Today the Taliban are alive and well in Afghanistan (Almukhtar, 2017, Roggio, 2017, Qazi, 2017, Mitchell, 2017, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2017). Suicide bombings and terrorist attacks are common and the Taliban have regained control of ~30-40% of the country (see Figure 2). This is partly because of the flawed U. S. mental models that Afghans would appreciate both being “freed” from their Taliban oppressors and the installation of a democracy; that they would understand that a few civilian deaths are inevitable; and that destroying the drug-based source of Taliban funding would be wise. Acting on these assumptions, The U. S. destroyed poppy fields, which happened to be the source of many rural Afghan’s income. Extensive civilian deaths were caused (as collateral damage) during allied air strikes. It is no wonder that we have lost the “hearts and minds” of most Afghans.

| Figure 2. Taliban Influence in Afghanistan (from Qazi, 2017) |

| Figure 3. Causal Loop Diagram Depicting the Rise of ISIS |

5. Discussion

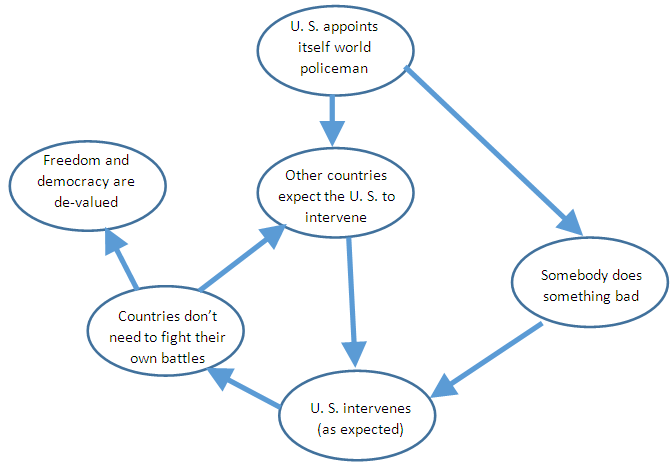

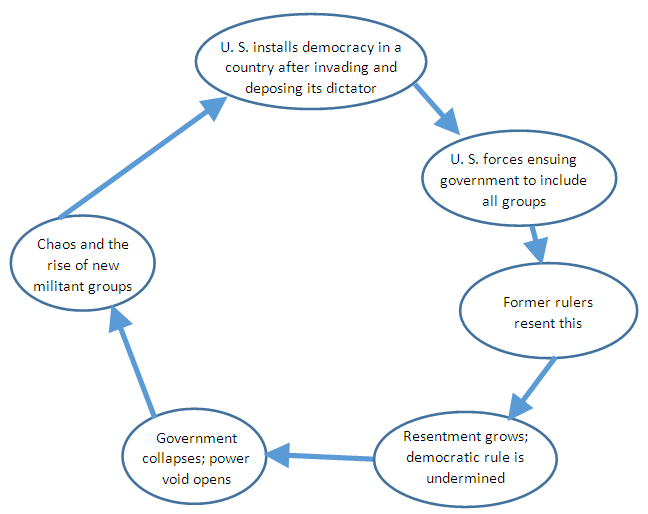

- The foreign policy of the United States can be characterized by major weaknesses in Systems Thinking: poor, unshared, inaccurate mental models; failure to appreciate feedback loops; inability to discover or understand systemic root causes; and misidentification of leverage points.Mental models such as the U. S. has the right and responsibility to serve as the world’s policeman; that democracy is the best form of government (and the U. S. has the right to impose democracy); and that the world shares our philosophical, spiritual, and political values are egocentric and inaccurate. Many of these derive from an inability or unwillingness to study and understand foreign cultures and ways of life. “The U. S. as the world’s Policeman” is a mental model held by some Americans, but widely resented by much of the world. Often, the same oppressed people who wanted the U. S. to intervene to repress a brutal regime end up hating the U.S. more than the oppressive regime. And freedom won by the U. S. military on behalf of an oppressed group is often devalued.Democracy may not always be the best form of government. In fact, majority rules in a pure democracy and the majority could deny rights to any and all minorities. The United States has a constitutional democracy based on the Constitution/Bill of Rights and supported by a legal system, which prevents the denial of rights to any citizen or minority. However, many Middle Easterners do not understand the concept that minorities should enjoy the same rights as the majority, and view a pure democracy as an opportunity gain control. For a democratic government to work, the people must agree that it is the highest law in the land. Democracy may not succeed in a land such as Iraq, in which religious doctrine (as opposed to secular law) is considered the highest law of the land. In Iraq, the ruling Bath party repressed the Shia majority for decades, and the imposed change to democracy provided an opportunity for the Shia to take revenge. Given the history of this region, the imposition of democracy resulted in an unintended consequence to the disadvantage of the Bath party. Systems Thinking analyzes the historical and political ramifications and potential unintended consequences of imposing democracy in Iraq, and concludes that democracy may not be the best form of government for that region. We would certainly resent it if an outside force attempted to impose Sharia law in the Unites States. Why would a non-democratic state view the imposition of democracy any differently? “People are willing to suffer some collateral damage to achieve philosophical, religious, and political ideals” is another poor mental model. When innocent civilians are killed during air strikes, their friends and families naturally resent it deeply. Some become militant or terrorist. It is therefore unclear if bombing actually reduces or increases the number of anti-American terrorists. Again, poor mental models often derive from egocentrism: an inability or unwillingness to understand another’s viewpoint. The U. S. repeatedly fails to study foreign cultures and values and assumes that all values reflect our own. We must do a better job of developing mental models, exposing them to scrutiny, and understanding the mental models of others.Linear thinking focuses on tactical, short-term reactions to situations without considering feedback loops. International actions inevitably result in reactions and unintended consequences: the toppling of Saddam Hussein yielding a power vacuum and the rise of ISIS; the arming of the Mujahedeen strengthening the Taliban and Al Qaeda; the support for the ARPCT in Somalia giving rise to Al Shabaab. Although we can’t always predict exactly what those reactions will be, failure to anticipate them is folly. And we have plenty of experience suggesting what reactions are likely to be: large scale invasions will likely yield a resistance; elimination of unappealing leaders will likely yield a power void; arming the enemies of our enemies will often empower a new enemy.We repeatedly attempt to deal with symptoms instead of underlying systemic root causes which often involve local culture and psychological needs. The appeal of radical, anti-American terrorist organizations is a symptom. Understanding the cultural basis for this appeal is essential. Many of the geographic areas in which we intervene are characterized by poverty, corruption, oppression, human rights abuses, or years of war and terror. Some local cultures are based on simony, a strong caste system, and nepotism, and youth born into poverty have little hope for a bright future. Appealing to these people with promises of democracy, equality for women, and a western penal code are folly when their basic needs are for food, shelter, healthcare, security, and an economic future. Groups like ISIS promise (and often deliver) these things and, whether totalitarian or not, will always be more appealing to people operating on the lower levels of Maslow’s hierarchy than will America’s ideological rhetoric.Alfred McCoy (2016) has a much better grasp of the systemic root cause of the Afghanistan conflict than do our own military and State Department. He writes, “We can continue to fertilize this deadly soil with yet more blood in a brutal war with an uncertain outcome… or we can help renew this ancient, arid land by re-planting the orchards, replenishing the flocks, and rebuilding the farming destroyed in decades of war… until food crops become a viable alternative to opium.” His statement applies equally well to many of our military interventions.Table 1 shows several iceberg models and the underlying mental models and structures that yield negative events.

| Table 1. U. S. Foreign Policy Iceberg Models |

| Figure 4. Causal Loop Diagram Showing the Devaluation of Freedom and Democracy due to the U. S. Self-Appointment as the World’s Policeman |

| Figure 5. Causal Loop Diagram Showing the Rise of New Militant Groups as a Result of U. S. Installations of Democracy |

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Over the past 40 years, America’s foreign policy has not been particularly successful. Our linear thinking, shoot-from-the hip approach has yielded negative consequences and could be viewed as having done more harm than good. A pertinent quote regarding Libya comes from NATO representative Ivo Daalder: “Could it have gone a different way with an outside military intervention? Possibly. But if we look at the last 25 years, the successes of those foreign interventions are few and far between……….. Clearly we’re learning a lesson, as we did in Iraq, as we did in Afghanistan, as we’re doing in Syria, as we did in the Balkans, as we did in Somalia and Mali et cetera. There’s a lot to be learned about how one intervenes with a result that is acceptable and a cost that is equally acceptable. We haven’t found that goldilocks solution yet and we probably never will, but it doesn’t mean we give up and never try or that we take ownership of these situations and put in troops to stay there for twenty or thirty years” (Robins-Early, 2015). Unfortunately, it is not clear that we are learning any lesson. The Goldilocks solution requires changing our way of thinking and re-assessing our ultimate objectives.1. With respect to foreign policy, the U. S. must develop and adopt better mental models, open them to scrutiny, and understand others’. “The U. S. has the responsibility to be the world’s policeman,” “Democracy is the best form of government,” “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” and “The world shares our political, social, economic, and spiritual values” are mental models that have not served us well.2. We must pay more attention to feedback and unintended consequences developing as a result of actions that we take. Initiatives such as the arming of the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan, the support of ARPCT in Somalia, bombings in Iraq (along with collateral damage), the destruction of poppy fields in Afghanistan, and the forced imposition of democracy in Iraq cause reactions from others. Indeed, almost every U. S. action results in pushback from someone. The growth of Al Qaeda, the strengthening of Al Shabaab, the resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan, and even the rise of ISIS are unintended consequences of our behavior.3. We must stop seeking the wrong goal, and work to understand the Systemic Root Causes of terrorism in the world. Our knee-jerk reaction typically is to respond militarily. But killing terrorists addresses the symptom, not the disease. Without understanding and addressing the root causes that give rise to terrorism, we will never eliminate it. This involves studying and understanding other peoples’ history, culture, values, and economic, political, social, and spiritual systems, and waging socio-economic wars instead of military wars. This is more difficult than sending in troops, but it is essential if we want to solve this problem.As Alfred McCoy (2016) says, “……. investing even a small portion of all that misspent military funding in rural Afghanistan could produce economic alternatives for the millions of farmers who depend upon the opium crop for employment. Such money could help rebuild that land’s ruined orchards, ravaged flocks, wasted seed stocks, and wrecked snowmelt irrigation systems that, before these decades of war, sustained a diverse agriculture. If the international community can continue to nudge the country’s dependence on illicit opium down from the current 13% of GDP through such sustained rural development, then perhaps Afghanistan will cease to be the planet’s leading narco-state and just maybe that annual cycle can at long last be broken.” Addressing the systemic root cause requires that we decide how the United States should exemplify leadership. Being the military tyrant of the planet has not proven successful. Investing in local systemic structures and mental models that will foster self-sufficiency with respect to food, clothing, shelter, security, and healthcare may prove more fruitful. To amplify Alfred McCoy’s suggestion, imagine that instead of spending $3 trillion dollars fighting wars in the Middle East (Kiley, 2016), those funds were spent on systemic improvements in housing, hospitals, economic development, and improved agricultural practices. Imagine that as a result of those activities, oppressed people saw a way out of poverty, corruption, and misery, and credited the United States for this. That would be leadership.We hope that our use of Systems Thinking principles to analyze some past foreign policy failures will stimulate the broader use of Systems Thinking by the State Department, military, and intelligence communities when dealing with international issues.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML