-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Systems Science

2014; 3(1): 1-11

doi:10.5923/j.ajss.20140301.01

“Talking about Innovation in Health Care…”

Pieter Kievit, Jeanette Oomes, Marianne Schoorl, Piet Bartels

Alkmaar Medical Centre, Foreest Medical School, Nassauplein 10, 1815 GM Alkmaar, The Netherlands

Correspondence to: Pieter Kievit, Alkmaar Medical Centre, Foreest Medical School, Nassauplein 10, 1815 GM Alkmaar, The Netherlands.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Quality improvement in health care by means of process innovation is notoriously difficult to achieve no matter how strong the evidence for the improvement in clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. The traditional solution to this problem is sought in more sophisticated management models based on more complicated representations of the innovation cycle and in strategies to overcome a supposedly mental resistance to change in individual professionals. The health care system however has a number of characteristics that impairs the efficacy of this approach. In this article we present the preliminary outcome of an investigation into the potential of Luhmanns theory of social systems to analyse the conditions for organizational innovation. The system – and the structure of discourse in which it becomes manifest - promises to be an effective framework for describing and analyzing support for or resistance to change based on the characteristics of communication in context. By introducing the system as focus of the dynamics of organizational development and the concept of discourse as a means to characterize the system in operation, we open up a potential new domain for semiotic research into the opportunities and threats determining success or failure of innovation projects. We continue this line of research with a number of validation studies in everyday practice in health service delivery organizations.

Keywords: Healthcare innovation, Immunity to change, Quality management, Discourse analysis

Cite this paper: Pieter Kievit, Jeanette Oomes, Marianne Schoorl, Piet Bartels, “Talking about Innovation in Health Care…”, American Journal of Systems Science, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.5923/j.ajss.20140301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In this paper we explore the potential of systems theory, discourse analysis and semiotic research to help solve one of health cares most urgent problems – the immunity to change of the health services delivery system[1]. This problem could be labelled as “the mystery of missing outcome” – no matter how evidence based the proposed innovation and how scientific the management, there seems to be hardly any causal relation between the input and the sustained outcome of the innovation process. Adoption of even the most convincing quality improvement in the health care system seems almost accidental. Our approach adds a focus on the human factor and the way in which people co-operating in social settings create shared meanings based on values that make concerted efforts toward a common goal possible – or motivate resistance to change. This form of co-operation between people within and between organizations is a complex phenomenon that is dominated by more than just the desire to reach a mutually profitable end. It is crucial that partners in co-operation do not only speak the same language but that they speak it in a sufficiently similar way. The additional approach we propose reflects many years of practical experience with quality improvement and innovation in hospital settings by a team of professionals from general management, quality management and systematic auditing.

2. Starting Point

- Innovation in healthcare, more particularly the implementation of evidence based quality improvement in clinical practice, is complicated and time consuming[2] while there seems to be no universally valid approach to increase return on investment[3]. In general, innovation as one of the foundations of competitive advantage and a mayor driver of both national economic growth and corporate profitability is a well studied phenomenon, leaving little room for doubt as how to manage the process from invention to market. Practical experience teaches otherwise. There seems to be a stubborn disjunction between the understanding of the necessity for change and the capacity of organizations to realize this change. At this point it should be stressed that the majority of management literature on the topic deals with technological innovation or product innovation whereas in healthcare, process and structure innovation are by far more decisive for quality improvement but far more difficult to realize. One of the basic models for imagining and managing innovation is the added value chain model[4]. In its most simple form the model describes the range of activities which are required to bring a product or service from conception, through the different phases of production, delivery to consumers and final disposal after use. In more elaborate forms the model is used to describe relations between partners in a process, companies, economic sectors and even areas of the world economy. The basic assumption implies that each step in a primary process (or link in a chain) adds value to the outcome of the stage before. This value is usually defined in an economic currency (financial of otherwise). Innovation in this model (both product innovation and service innovation) is driven by the urge to “upgrade” or to improve: outperform the competition in adding value or to add greater value than before or without the innovation. Challenges concerning the model of chain innovation are twofold: the “unifying currency” and “ceteris paribus” fallacies. In the first place the currency in which added value over the chain is expressed, is an economic currency. The currency will always be considered as a rational value, being rated as a number or a score on a scale. As such it is a currency that could and should be shared as normative between the partners in the chain in order to unify them within the model and identify them as partners in the first place. This presupposes a degree of similarity in values between partners that is far from guaranteed within the health care sector. The second challenge to the concept is that it is a ceteris-paribus model. It operates under the condition that all elements in the model act and react in terms of the model only. Put differently: it acts on an assumed representation, abstaining from experienced reality, for the benefit of conceptual clarity and the illusion of control. Whenever reality breaks through the surface of the representation, thereby endangering the cost-efficiency and outcome of the innovation process, the answer is sought in stricter process control and more sophisticated management models: ”Transitions are represented as a set of factors or conditions that, if they all work together, will cause a desired change – as if they are the result of more or less mechanical, instrumental processes. However, according to transition experts it is a misconception to presume that the implementation of the theory will lead to a deterministic collection of directing rules and to a linear production of desired effects”[5].

3. Innovation in Health Care

- Compared to other sectors, the sector of life-sciences and health reveals a number of specific challenges when it comes to innovation and evidence based quality improvement (“valorisation”). One of these is the compound character of the organizational context. In the domain of health services and clinical intervention, participants with different characteristics have to interact to deliver the outcome – and hence to adopt the innovation improving this outcome. The most important are the medical professional, the healthcare institution, the payer organization, policy makers, private companies and the patient. They are managed on different concepts, driven by different incentives, are oriented on a different world view and carry different responsibilities. But most of all they have a specific perception of themselves and the partners in the field. One of the consequences of this diversion is that there exists no shared denominator to express value over the chain: the common currency[10]. Another consequence is that the strategies of scientific management and HRM will not apply to all elements in the model in the same way, thereby complicating managing innovation and change over the chain.In the sector of life science and health the linear (cyclical) model of innovation does not easily fit. In this standard model, innovation is seen as the outcome of a number of consecutive stages: knowledge creation (research), knowledge synthesis (combining information from research with information from policymakers and practitioners in order to promote the use of knowledge), knowledge application creating guidelines, products etc tailored for a specific area and finally implementation – the process whereby the outcome of research in the form of applications is introduced into practice and policy. The standard linear model assumes that each of these stages is carried by a (type of) organization, unified in a policy model consisting of agenda setting, program development, program realization and valorization of outcomes in the form of increased knowledge, policy development and/or market propositions[11][12]. The standard model for innovation emphasizes the coherence of activities within the cycle and the way in which partners co-operate under a shared (if not formalized) perspective on outcome – within this ”linear model” (also known as the Traditional Stage Gate Model) of the cycle they seem interconnected as links forming a chain. This model has been criticized as an idealized abstraction of reality fairly early[13] and in response to the criticism it has both been defended[14] and further developed[15]. The most recent offspring from this line of conceptualization is the so-called “Assisted linear model of innovation” on which many Technology Transit Organizations are based [16][17]. Whenever the validity of the standard cyclical model as a guideline for innovation appears to be refuted by practical experience, the primary reaction consists of either a call for more - or more sophisticated - management on the cycle itself or a total abandonment of all conceptualization, invoking contingency or the irrational concept of “serendipity” as decisive factor in innovation – as illustrated by James le Fanu[18].We propose not to abandon reason and rationality in designing and operating a model for managing innovation processes in the domain of healthcare, but we enrich actual models with an additional perspective on mechanisms by which organizations and professionals co-operate in a complex environment.

4. Alternative Approach – enter Systems Theory

- Our point of departure is the observation that the ability of an organization to foster change and its capacity for innovation based on co-operation cannot be derived from its formal properties or characteristics or be reduced to the mental state of individuals participating in that organization. A new explanatory model is called for. We derive a new model from the social systems theory formulated by N. Luhmann on the basis of earlier work by Umberto Maturana and Fransisco Valera[19][20][21][22]. Central to the theory is the concept of social systems: “…a system may be described as a complex of interacting components together with the relationships among them that permit the identification of a boundary-maintaining entity or process[23]. This means that a system is not an entity or a compound phenomenon like an organization – it is a dynamics of relations constructing, reflecting and transmitting shared values that enable the system to experience itself in terms of self and other, belonging and rejecting, coalition and opposition.The process by which a social system defines itself over time in terms of identity and difference is called “autopoesis”. This autopoesis is realized in communication: ”...the basal process of social systems which produces their elements, can only be communication” [24][25]. As a consequence, a system can be defined as the sum of communications taking place between the elements of the system that are in their turn defined by participating in that communication. Communication denotes the process whereby a sender transmits bits of information to a receiver referring to a state of affairs through a medium (channel), regularly checking the status of the transfer[26]. This is not sufficient to constitute a system which is always situated in time and place. Jakobsons traditional communication model abstains from local and temporal determination. In this, the model reflects its origin in De Saussure’s two faced sign model which focuses on “structural relations between linguistic forms” and insists that these forms “are severed from meanings, understood as preexisting entities in the mind or in the world”[27], thereby reducing communication to “…a process comparable to the exchange of telegraphic messages” and conjuring up “…the well known social monster: the ideal speaker-listener”[28]. In the course of time there has been no shortage of efforts to address this conceptual abstraction in the standard model of communication. Several extended models have been presented, embedding communication in societal environment and thereby adding the aspect of context-dependancy to the concept of sign. All these models aim at introducing the diverse aspects of context influencing the act of communication but leave the sign itself, the binary coupling of an utterance and an object unchanged, hereby leaving the element of stasis in the original concept untouched.Luhmann does address the issue of context-dependancy of communication by adding the principle of “action” - attributing the act of communication to an actual speaker in relation to an actual (and understanding) listener as a process of selection: “...thus we give a double answer to the question of what comprises a social system: communications and their attribution as actions”[29] or: “Communication is the elemental unit of self-constitution and action is the elemental unit of social systems' self-observation and self-description”[30]. Communication as a phenomenon however is not elaborated upon in the systems theory as developed by Luhmann thereby leaving unexplained the mechanism by which communication facilitates and dominates autopoesis [31].Communication as a process defining a system does not occur in a vacuum but always within the context of a social setting in time and place that realizes communication in the form of discourse. In this sense, discourse is communication embedded in a normative grid defining the permissible value for the elements in the actual communication. Whereas the communication model is based on the concept of a sender and a receiver, the embedding concept of discourse determines just who can act as sender and receiver in a given communicative situation and whereas the communication model states that communication is about a subject, the concept of discourse determines which subjects are permissible topics in any concrete conversation and what might be the value of any statement concerning that topic. Discourse is communication in action – or “communication” is to “discourse” as “langue” is to “parole” in the theory of De Saussure[32]. Replacing “communication” with “discourse” as the mechanism (based on communication combined with action) by which a system defines and replicates itself (autopoesis) does justice to the fact that a social system is not an abstract entity, a set of defining relationships, but rather a meaning- and thereby value generating process that develops in an actual societal context. The shift of attention from communication to the context in which it takes place opens up a wide field of additional questions – evolving around one issue: how does discourse actually frame communication? But first a different question should be addressed - what is the relevance of this approach for the problem of process innovation in health care? As stated before – and confirmed in evaluation studies – co-operation within and between the diverse parties which are involved in health care delivery and innovation is a multi factorial phenomenon that cannot be grasped by the formal concepts of traditional organization research and mental analysis. What is at stake is the very core of organization – the mechanism by which people forming an association produce the values that unite them in a common purpose and in so doing establish an identity as a group over time. This mechanism is communication according to Luhmann and others, but communication as a concept demands further analysis. If communication is to be the mechanism by which identities are constructed and maintained, then it is necessary to deconstruct the concept and see what actually happens when people communicate. Therefore we have to take closer look at the basis unit of a communication process, the nucleus of meaning – the sign.

5. Linguistic Twist

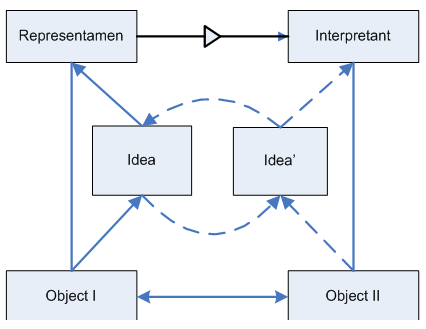

- Traditionally the linguistic sign, the fundamental particle of meaningful exchange between people, is conceived by De Saussure as a unit consisting of a “signifiant” and a “signifié”- or a “signifier” and the “signified”, represented by the image of a coin. In this model the signifier is the outward form of the sign – for instance the utterance – whereas the signified is the object or state of affairs, carried or evoked by the utterance. In De Saussures founding paper, the complicated, bi-conditional relation between an object as part of a state of affairs and the consciousness of the same in a knowing (and communicating) subject has been excluded from the concept of sign as this problem is considered to be an epistemological problem and as such not relevant for the emerging empirical science of linguistics[33]. With De Saussure, the reference to reality is unbroken by doubt concerning the nature of the relation between the world of objects and the knowing subject, between consciousness and being (or res cogitans and res extensa). Problem with this exclusion is that the act of communication is reduced to a binary en- and decoding operation between two neutral operators, eliminating intentionality as a determining element in establishing meaning (defined as reference). Thereby any opportunity for development and change of either the signifier or the signified is impossible – consequently freezing the concept of meaning into an eternal “semper idem”. The aspect of evolution, the dynamics of change, the creative potential established by communication calls for a model of the sign that includes a reference to the world beyond signifiant and signifié, to the experienced context in which communication between people takes place. This is exactly what is supplied by the pragmatic model of the sign in the semiotics of Charles Sanders Peirce[34]. Here the concept of “reference” as the dynamics between the perceived object (as part of a state of affairs) and the knowing subject and expressed as the “idea” of the sign in the act of communication between partners becomes the central issue. Basic to the concept of sign in Peirce’s semiotics is the act whereby something is perceived as something in an intentional act of recognition and subsequent transfer. This act is condensed in the “idea” unfolding its aspects in the act of communication with the other, the “alter ego”.The process of communication as described by Peirce hinges on the mechanism by which a sender and receiver try in common effort and following pre-established and continuously tested rules to reach agreement on issues relevant to both in the respective contexts. This agreement can be defined as reaching a minimal necessary degree of congruity between idea and idea’. This degree of congruity should be sufficient for the practical purpose that drives the need for communication in the first place: it should be able to support the practical action (s) that that are envisaged by the communication. This is especially important as all social systems are per-sé intentional – people gather together to reach a certain goal, they co-operate to realize an intent. Whether or not the degree of congruity is indeed sufficient to enable the system to reach this goal or not is established in and by the outcome of the practical interaction of which the act of communication is the representation: “Das Verstehen erwächst zunächst in den Interessen des praktischen Lebens. Hier sind die Personen auf einander angewiesen. Sie müssen sich gegenseitig verständlich machen. Einer muss wissen was der andere will”[35].

6. Concept of Discourse

- We propose that “discourse” be the organon of autopoesis in that it represents the operation of a set of rules which determine valid communication within a social system – thereby defining that system. We consider that communication always refers to states of affairs – that which is the case (Wittgenstein: “Die Welt is alles was der Fall ist” – the proposition which opens his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus) – and that discourse is defined by the set of operators which determine the way in which these states of affairs can be addressed thereby forming and defining a social system.Therefore: discourse represents the actual set of operators which determine valid communication in action defining a social system within a context relevant to the system.How to specify these operators? As stressed earlier, a social system is not an entity or a structure – it is a temporal focus of shared values and strategies maintained and dominated by forces of attraction and repulsion - not unlike gravity. As such, a system relates through identification and differentiation with all systems within the wider context of society as the arena where parties participating in innovation meet and deal with one-other in a common (political) agenda. As a consequence, on the one hand, values dominating a systemic discourse will always reflect broader societal values on penalty of exclusion of the system, labeled as a “solus ipse”. In addition, social systems operating in the context of a shared agenda aimed at providing and innovating healthcare will share a number of basic concepts that are sufficiently general to be considered universal for the sector – again on penalty of exclusion as a relevant partner-system. So the way in which a discourse is structured will reflect con-current discussions on social values as well as issues concerning the way the health care sector is structured and organizations are managed. This debate on societal values and organizational features occurs in three key areas: ● The dynamics of interaction ● The value of argument● The concept of change In these three areas, relevant socio-political debates are reflected as well as the main characteristics of organization: style of leadership, orientation on surroundings and sense of continuity, including concepts of the past in terms of future.

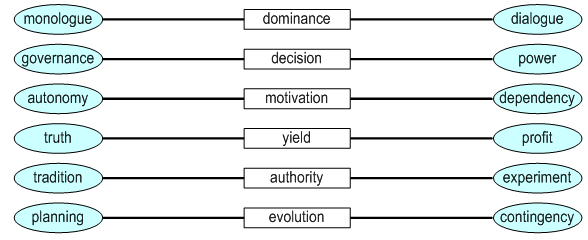

6.1. Dynamics of Interaction

- As Luhmann has stipulated, in communication the functions of sender and receiver are attributed as actions to a participant. In discourse this attribution is determined by rules reducing the scope of possible attribution to what is acceptable within the system reflected in discourse. What is at stake here is “…the control over discourse itself: who is speaking in what context”[40]. In this we follow Teun A. Van Dijk who concluded that both “…theoretical analysis and (our) review show that whether in its direct or indirect forms, power is enacted and reproduced in and by discourse”[41]. The same point is stressed by e.g. Norman Fairclough et al: “Since discourse is so socially influential, it gives rise to important issues of power”[42]. But how do the dynamics of power become manifest in the discourse that shape a social system? This aspect of power become apparent in two dimensions: “dominance” and “decision”.Dominance: communication is characterized by the alternation of the function of sender and receiver between the participants in the process. This distribution of function over time is by no means evenly. In every communication there will always be a distribution of dominance and thereby of influence on the direction and outcome of the communication. The defining endpoints for this dimension are “monologue” versus “dialogue”. The discourse element of “dominance” reflects the broader issue of in- and exclusion in society which is the focus point in any discussion on theory and practice of social justice. It is the question of whose arguments are considered in discourse – who is a participant in the socio-political arena and who is not. Decision: in most cases communication will lead to some kind of conclusion. This need not be a formal decision or a call to action – it might very well be a shared opinion on the state of affairs that was the reference of the messages transmitted or an agreement to disagree or even just a friendly but non-committing hand shake. The way in which a conclusion is reached, is characteristic of the dynamics of interaction. Conclusions can be reached either by the expression of will or trough a set of rules determining how to reach a conclusion. The defining endpoints for this dimension are “power” versus “governance”.The operator by which a “decision” is reached in discourse reflects the social issue of legitimacy or the question whether a decision is based on authority and power or grounded in (democratic) procedure as an expression of governance. Here lies the discussion about the base of organizational power structure, whether it should be founded in the qualities of a leader or in the continuity and security provided by procedure.

6.2. Value of Argument

- All communication consists of statements reflecting a state of affairs external to the message being transmitted and received (except in fiction which is self referential). These statements are selected and supported upon a motive that has a trading value in the argument. Two dimensions are dominant on this aspect: motivation and yield.Motivation: crucial to social systems theory is the dynamics whereby a system relates to other systems in its perceived environment. The value of a motive in communication can either be derived from the notion of self (identity) or from the relation to the perceived other (the relation). We call this aspect “motivation” because it denotes the explicit impulse for action – which is either driven by internal motives or in perspective to some other (on behalf of or against). The defining endpoints for this dimension are “autonomy” versus “dependency”.The element of “motivation” as a source for assigning additional value in discourse refers to the social debate on autonomy and coherence as determinants of social dynamics. It is the issue of the ultimate raison d’être of a system – is it motivated by outside orientation of by internal drive. Yield: a system has to maintain itself in a struggle against entropy that requires continuous investment in terms of time, finances, creativity and energy, investment which can only be realized under an anticipated gain as return on the investment. The value of a motive in communication is related to the nature of this projected return of investment. There is a choice here between principle or pragmatics – undertaking an action for its own sake (inherent value) or because of an expected return (added value). The defining endpoints for this dimension are “truth” versus “profit”.“Yield”, the perspective of added value in discourse, reflects the wider issue of political pragmatics or the consideration between the quest for ethics and truth or a search for benefits and profit. The point in question is which adds weight to an argument in discussion – doing that which is right for its own sake or going where profit (and continuity!) is to be found.

6.3. Concept of Change

- Communication defining a system is multi functional. One of the functions is to reflect the present in terms of a shared concept of past and the challenges of the future. This aspect determines the orientation of a system in time and the possible scope for action. Two dimensions are dominant on this aspect: authority and evolution.Authority: one of the aspects of assigning value to arguments in communication is reflecting the past or anticipating as yet unknown future possibilities. Arguments can be supported by recourse to a time honored position representing a superior standard and authority or by evoking the demands of the future requiring a breach with time honored - but obsolete – values and practices by way of trial and error, using the outcome a support for argument. Referring to the classics, untainted by time or leaving the restraints of origin, to be prepared for the unexpected. The defining endpoints for this dimension are tradition and experiment. “Authority” as an element of value in discourse relates to the very foundations of society – is it grounded by referral to founding fathers from the past or by experiment open to the challenge of the future? It is the question of what adds legitimacy to an argument – support form tradition and immovable truths or support from as-yet unproven assumptions to be tested in experiments. Is a system open to the future or a standard bearer of established values?Evolution: a social system not only relates to its environment (synchronicity) but also locates itself in the diachronic sequence of events that define history – interpreting the past and anticipating the future. In discourse a shared view on development comes to expression where there are two possible positions. Development as a predictable sequence of cause and effect, dominated by serial bi-conditional equivalence or development as a series of contingencies in the form of single implications. The defining endpoints for this dimension are planning and contingency. The operator “evolution” is based on the general concept of progress as either the outcome of planned action within a framework of valid predictions based on a rational reconstruction of past and present or the result of incremental social engineering in a universe of contingency. This determines the scope of meaningful intervention. In a closed universe where the reaction to each and every action is foreseeable, management is a science based on applying “…golden rules associated with linearity: reductionism, predictability and determinism”[43]. In a universe dominated by co-incidence and random effect of accidental occurrences management is far less likely to take a meaningful decision.So the dynamics of discourse by which is established in which way communication can be realized in action, determining the identity and difference of a system in relation to others is dominated by six dimensions on three aspects.

7. On Method

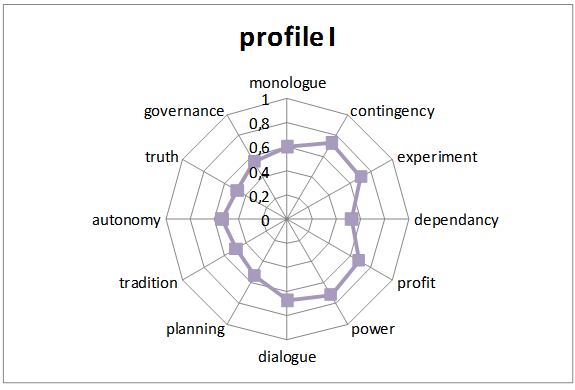

- Next question is how to analyze a manifest system in order to establish the distinctive properties of the discourse by which this system expresses itself in values constructing identity and difference – thereby enabling the system to enter into meaningful co-operation with others within the framework of policy.The way in which a discourse based profile defining a social system is constructed, proceeds in two steps.First the grid is laid out. In this grid the six dimensions with their defining endpoints are graphically reproduced as an image of six lines. Among many this could be in the shape of a stave or a radar chart.

| Figure 3. The six dimensions of discourse |

| Figure 4. The plotted profile of a system, indicating that the structure of discourse favours easy adoption of innovation and propensity for change |

7.1. Definition of Endpoints

- The defining endpoints of a dimension are not context-independent in that they could be observed as such in form of a universal attached to a system. Whether decisions are reached through regulated vote or by word of power, whether arguments are valued as echoes from a glorious past or as windows on a possible future, whether a system sees itself as link in a rational cause-and-effect sequence or suffering “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” (of course: Shakespeare, Hamlet, act three, scene one, line 56/57) is not fixed as an invariant label to the system. Instead we will have to make do with intermediate endpoints or surrogate markers: features or properties of the actual communication or semiological domain embodying the system under investigation that reflect the formal or primary endpoints defining the dimensions.In this domain those elements are selected which best reflect the endpoints in the model, thereby applying the dimensions themselves to the actual domain and actualizing the model in terms of the discourse that produced the domain. This is the act of interpretation: establishing the relation between the model (the paradigm) and its loco-temporal realization or the actual representation of the model, thereby assigning dimensional functions (“universals”) to the elements of the domain (“instances”). Once the surrogate endpoints within the domain have been identified, the act of attribution ensues, bringing the elements of the domain in ranking relation to the endpoints of the dimension thereby establishing the profile of the discourse defining the system that is under investigation.The acts of interpretation and attribution are not mechanical operations, performed by an unwitting agent. They are not mathematical procedures but a real life interaction between a knowing subject and the living substance of other knowing subjects forming a loco-temporal association of values defined as a system – in this sense analyzing a domain in terns of discourse is nothing but a process of hermeneutics[45][46].

7.2. Producing a Score

- The next question will be how to reach a score on the six dimensions establishing the structure or pattern of discourse under investigation. For this tools are needed that will be suited to the nature of the domain in which discourse manifests itself and the particular question that drives the research. The nature of the domain and of the question determine the range of tools available. That implies that a vast variety of instruments, provided by the social and cultural sciences, will be appropriate to any given research project, related to the domain, the research question and the problem to be solved – as long as they are suited to transform an observation into a score on a scale. A basic distinction must be made between tools for “immediate” and “intermediate” analysis of discourse. Immediate (or observational) analysis operates on communication in process by observation either in vivo or based on a registration of life action for instance in the form of minutes or video, while intermediate analysis operates on the sediment of communication, the domain consisting of text, imagery and symbols embodying founding and maintaining rituals and decisions taken. The third aspect of discourse analysis is the questioning of individuals deriving part of their identity from co- constituting the system. Questioning subjects – individually or in groups – is a very well established research practice in the social sciences, including psychology – providing an abundance of tools.

7.3. Profiling a System

- Systems will show a considerable consistency in the way they structure and maintain their identity. This implies that the distribution of values on the dimensions of discourse needs to be similar for each method applied either in observation or domain analysis. The strength of any one analysis will be enhanced if the findings are corroborated by multiple concurrent analyses.Next to this internal consistency there will be a temporal continuity – a system will be stable for any duration of time in order to be able to function in a societal context in relation to other systems within the same agenda. This means that the discourse profile will need to show stability in a number of consecutive analyses. A minimal required degree of congruity between systems is the precondition for successful co-operation within an common agenda – for a single intentionality to combine to shared intentionality as a social (political) effort. This is why profiling a single system does not add to our understanding of any specific innovation process or change effort. In order to determine the feasibility of any intended process innovation it will be advisable to determine the susceptibility to change of the combination of systems that are involved in the effort – in order to be able to address the possible discrepancies in the discourse profiles that characterize the systems.

8. Next Step: Application in Practice

- The concept of discourse as a means to determine the mechanisms by which a social system defines and prolongs itself (“autopoesis”) and is able to interact with systems within the same agenda is as yet a mere theoretical exercise, albeit supported by literature and practical (reflected) experience.Our next step will be to apply the concept to a number of actual organizations (as representatives of social systems) to determine whether it’s possible to construct an “innovation profile” by means of scoring the six dimensions. The ensuing research program will consist of two phases:

8.1. Testing the Instrument

- We propose a series of case studies in order to test the validity and reliability (stability and internal consistency) of our approach: discourse analysis of a number of systems that are generally considered to be more or less open to change and carriers of innovation in the field of health care delivery - aiming at differentiating between systems at the higher and lower end of the “innovation-conservation” spectrum. Leading in the selection of systems is a peer estimation. A number of validated tools from the research domain of social sciences and linguistics will be applied to the domain of the selected systems under the assumption that the ensuing profiles will show sufficiently stable and internal consistent pattern similarity for each analysis.

8.2. Applying the Instrument

- Once the case studies have proven that discourse analysis on the model of six dimensions does indeed differentiate between systems according to their capability to support innovation and endure change – and hence their capability to cooperate with other systems within the same agenda, the method will be applied to any number of real life cases of process innovation, either successful or less so. The results will serve to improve the method itself and to provide feed-back to the participants in the project in order to provide a stimulus for improvement.

9. Discussion

- From many years of experience with quality improvement and process innovation in hospital settings it can be conjectured that ineffective management and mental resistance to change in individual professionals cannot by themselves account for the lagging implementation of new best practises - even though supported by the strongest empirical evidence - in health care organizations. There is a hidden dimension of immunity to change that eludes the managerial concepts of transition in health care. This hidden dimension of organizational dynamics, determining the degree of changeability, is that of the “system” - in its manifestation as discourse it is a set of rules defining the way in which meaning is created based on shared values but it also provides the identity of groups of people adhering to these values and through adherence both sustaining and developing them. This “system” is not something that can be observed immediately in operation – its existence and development can only be inferred by the traces it leaves as its domain: the sediment of discourse, the experience of people and the observable implicit and explicit rules of communication in action. It is not so much the cooperation between individuals or organisations that advance or obstruct the adoption of quality improvement through process innovation – it is the susceptibility to change of a system and the degree of compatibility between the systems involved in the necessary changes. Systems theory, discourse analysis and semiotic research in this context is a novel and as yet untested approach to one of the most stubborn problems in health care innovation – the apparent immunity to change of the organizations – and professionals - concerned.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML