-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Stem Cell Research

p-ISSN: 2325-0097 e-ISSN: 2325-0089

2018; 2(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.ajscr.20180201.01

Reducing Lumbar Discogenic Back Pain and Disability with Intradiscal Injection of Bone Marrow Concentrate: 5-year Follow-up

Kenneth Pettine M. D.1, Maxwell Dordevic1, Michael Hasz M. D.2

1Research and Development, Celling Biosciences, Austin, USA

2Spine Institute, Virginia Spine Institute, Reston, USA

Correspondence to: Maxwell Dordevic, Research and Development, Celling Biosciences, Austin, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background Context: Surgical treatments of discogenic lumbar back pain are fusion or lumbar artificial disc replacement. Studies comparing lumbar fusion with nonsurgical treatment found no difference in clinical results. Studies comparing lumbar fusion with lumbar artificial disc replacement have had mixed results. In a study with 12-month follow-up, our colleagues reported that intradiscal injections of autologous bone marrow concentrated cells resulted in substantial reductions in pain and disability without treatment complications or other adverse events. Purpose: This article reports a 5-year follow-up of treating lumbar discogenic back pain and disability with bone marrow concentrate. Study Design/Setting: Prospective, open-label, single-center case series. Patient Sample: The initial 26 participants were all surgical candidates according to their history of low back pain, nonsurgical treatment, and measurements of pain, disability, and disc degeneration. Outcome Measures: Visual Analog Scale of pain, and Oswestry Disability Index. Methods: Study design and clinical protocol, bone marrow collection and processing, and intradiscal injection were as previously described in the initial report. The study did not receive any outside funding. The disposable aspiration kits for the BMC injections, which cost about $20 each, were provided without charge by Celling Biosciences, Austin, Texas. Results: Of the initial 26 participants, six proceeded to surgery within 3 years of follow up. Of the remaining 20, 19 were available for follow-up at 5 years. Absolute and percentage reductions in pain and disability scores were sustained through the 5-year follow-up. No adverse events were reported through the 5 years. Conclusions: It may be reasonable to consider injecting participants who have discogenic back pain at one or two levels with bone marrow concentrate before they proceed to surgery.

Keywords: Lumbar Discogenic Back Pain, Bone Marrow Concentrate, Fusion, Disc Replacement

Cite this paper: Kenneth Pettine M. D., Maxwell Dordevic, Michael Hasz M. D., Reducing Lumbar Discogenic Back Pain and Disability with Intradiscal Injection of Bone Marrow Concentrate: 5-year Follow-up, American Journal of Stem Cell Research, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.ajscr.20180201.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A fact sheet from the United States Bone and Joint Initiative summarizing the burden of musculoskeletal diseases states that one in four adults in the United States suffers from chronic low back pain, with a cost of more than $250 billion in treatment and lost wages [1]. Surgical treatments of lumbar discogenic back pain are fusion or lumbar artificial disc replacement (LADR) [2, 3, 4]. A 2-year follow-up study [5] and a 4-year follow-up study [6] compared lumbar fusion with nonsurgical care. They reported no differences in clinical results. One study with a 2- year follow-up [7] concluded that LADR is as least as good as fusion. Another two studies with a 2-year follow-up [2, 3] reported that LADR is superior to fusion. However, one of these studies continued to a 7-year follow-up [7, 8]. This study concluded that outcomes after LADR were similar to those after fusion. A 5 to 10-year follow-up study [9] of LADR clinical results showed substantial improvements in VAS and ODI from baseline at all follow-ups. However, this study also reported that these improvements deteriorated from 48 months after LADR. Furthermore, complications occurred in 26 (14.4%) of the 181 participants who were followed- up.In 2015, we [10] reported a 1-year follow-up about the use of intradiscal injections of autologous bone marrow concentrated cells (BMC) to treat moderate to severe discogenic back pain in one or two levels in 26 participants. In a single, 45-minute outpatient procedure done under conscious sedation, bone marrow cells were aspirated from the iliac crest, concentrated by centrifugation, and injected into the nucleus pulposus of one or two symptomatic, degenerated discs. The participants had had a history of least 6 months of low back pain and at least 3 months of nonsurgical treatment without resolution. The mean pretreatment pain score as measured by the 0 mm to 100 mm Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [11] was 79.3 mm, and the mean pretreatment disability score as measured by the 0% to 100% Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) [12, 13] was 56.5%. They also had a grade of 4 or greater on the 8-grade modified Pfirrmann MRI [14] classification, indicating moderate to severe disc dehydration and degeneration. All were surgical candidates.By 3 months, the mean VAS and ODI scores were 29.2 mm and 22.8%, statistically significant decreases sustained through 1 year. By the end of the year, 24 (92%) of the 26 participants had not proceed to surgery. Of these, 20 had an MRI to assess the change in Pfirrmann grade. Eight (40%) of these 20 had decreased degeneration in their treated discs as shown by a decrease of at least one Pfirrmann grade. The other 12 had no change.Although participant age and gender had little effect on reductions in pain and disability, the concentration of mesenchymal stem cells did. At 3 and 6 months after injection, participants receiving of at least 2,000 colony forming units of mesenchymal stem cells per milliliter experienced substantially faster and greater reductions in VAS and ODI scores than those receiving fewer cells. However, the differences between these two groups were not statistically significantly different at 1 year.We then reported on 2 and 3-year follow-ups [15, 16]. By the end of the second and third years, the decreases in VAS and ODI scores that had been observed at the end of the first year were sustained in the participants who had not undergone surgery. No adverse events were reported through 3 years.Between the first and second years, three participants underwent surgery. Between the second and third years, another participant underwent surgery. Thus, through 3 years of follow-up, 20 (77%) participants of the starting group of 26 avoided surgery. Here we report on the findings of a 5-year follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

- Study materials and methods were as described initially [10]. All participants provided written informed consent according to the form provided by Western Institutional Review Board, Puyallup, Washington (clinical study protocol approval number 20120085). The $5,000 per participant cost of the BMC treatment and costs of subsequent follow-ups were provided at no charge. The study did not receive any outside funding. The disposable aspiration kits for the BMC injections, which cost about $20 each, were provided without charge by Celling Biosciences, Austin, Texas.For the 5-year follow-up, the remaining participants underwent VAS and ODI scoring, and they were asked how they felt and about how often they took opioid pain relievers. The six participants who progressed to surgery after BMC injection were contacted about they felt and how often they took opioid pain relievers. The study did not receive any outside funding.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Retention

- Of the 20 participants who underwent BMC injection and had not proceeded to surgery, one could not be located and was lost to follow-up after the 3-year report, for 95% follow-up.

3.2. Participant-reported Outcome Measures

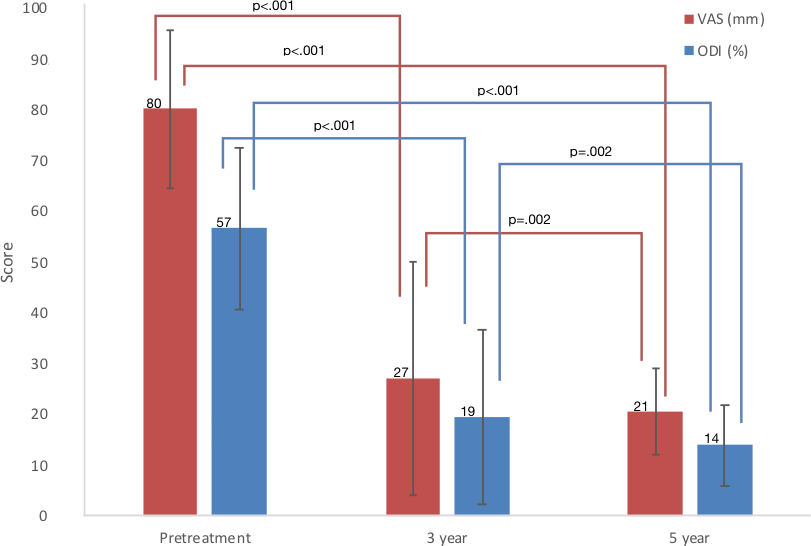

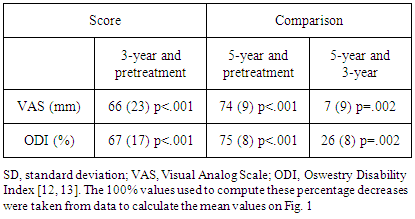

- Absolute and percentage reductions in VAS and ODI scores were sustained through the 5-year follow-up (Fig. 1 and Table 1, respectively). The 5-year mean VAS and ODI scores were both statistically significantly less than the 3-year scores. At the 5-year follow-up, eight (42%) of the 19 participants who had not proceeded to surgery reported that their back pain was either 90% reduced or to within pain and disability scores typically reported by adults ages 40 years and older unaffected by back pain, a VAS of 2 mm or less and an ODI of 10% or less [17]. From 3 years to 5 years, 5 of the 19 participants had increased disability as shown by increases in ODI scores from 3 to 5 years: 0% to 6%; 4% to 10%; 6% to 10%; 12% to 14%; and 14% to 22%.

|

3.3. Adverse Events

- As previously reported [16], there were no adverse events through 3-year follow-up. For the 19 participants who underwent BMC injection and were evaluated at the 5-year follow-up, no adverse events were reported between the 3-year and 5-year follow-ups.

3.4. Proceeding to Surgery

- As previously reported [16], six of the original 26 participants proceeded to surgery through 3 years of follow-up. With the possible exception of the one participant who was lost to 5-year follow-up, no additional participants proceeded to surgery after the 3-year follow-up. Through 5 years, two of the six participants who proceeded to surgery after BMC injection had good surgical outcomes in that they felt better than they did pretreatment.

4. Discussion

- Of the 20 participants who initially underwent BMC injection and did not proceed to surgery, 19 were followed up for 5 years. Overall, pain (VAS scores) and disability (ODI scores) continued to decrease from scores reported in the 3-year follow-up [16]. The increases in disability reported at 5 years in 5 of these 19 participants were only slight. In contrast, only two of the six participants who proceeded to surgery within 3 years after the BMC injection had good surgical outcomes. At 5 years, opioid use was substantially less in the BMC-only participants compared with those six who proceeded to surgery.Meanwhile, no participant proceeded to surgery after the 3-year follow-up. Compared with pretreatment pain and disability, no participant was made worse from the BMC injections. No adverse events were reported since the 3-year follow-up. Thus, through 5 years, no serious complications or adverse events were associated with the BMC injection.The results in this study of using bone marrow concentrate to treat discogenic back pain with 5- year follow-up were superior to the 2-year results of lumbar fusion or LADR [2, 3, 7]. Inasmuch as studies [5, 6] comparing lumbar fusion with nonsurgical care reported no difference in clinical results, BMC injection appears to be superior to lumbar fusion surgery in cases of chronic discogenic back pain. The continuing success for most of the 26 initial participants indicates that BMC injection is sustained for as long as 5 years with minimal safety concerns. And as noted, the cost of the BMC treatment was $5,000. This cost was considerably less than the cost of fusion, $50,000 to $75,000, or of lumbar artificial disk replacement, $35,000 to $45,000.

5. Conclusions

- To our knowledge, our previous reports [10, 15, 16] and this report are the only ones about use of BMC to treat discogenic lumbar back pain and disability. It remains to be determined if the favorable results of this small, preliminary study will continue to be sustained. The study lacked a randomized control group, and MRIs were not done long-term. Nevertheless, we conclude that intradiscal treatment with bone marrow concentrate offers a promising approach to treating lumbar back discogenic pain. It may be reasonable to consider treating patients with who have discogenic back pain at one or two levels with bone marrow concentrate before they proceed to fusion surgery or to artificial disc replacement.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML