-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Polymer Science

p-ISSN: 2163-1344 e-ISSN: 2163-1352

2013; 3(5): 83-89

doi:10.5923/j.ajps.20130305.01

Preparation of Epoxy Functionalized Hybrid Nickel Oxide Composite Polymer Particles

Mohammmad S. Hossan, Mohammad A. Rahman, Mohammad R. Karim, Mohammad A. J. Miah, Hasan Ahmad

Department of Chemistry, Rajshahi University, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Mohammad A. J. Miah, Hasan Ahmad, Department of Chemistry, Rajshahi University, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Preparation of inorganic–organic hybrid materials is attracting much interest as such elaboration produces remarkable improvement in properties and versatility in application potential. In this investigation, nanosized nickel oxide (NiO) particles were first prepared by calcination of nickel hydroxide precursor obtained by a simple liquid-phase process. The produced NiO particles were functionalized with oleic acid followed by silane coupling agent. Finally attempt was made to prepare epoxy functional hybrid NiO/poly(methyl methacrylate-glycidyl methacrylate) abbreviated as NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles by seeded copolymerization in ethanol media. The composite particles were colloidally stable, and the obtained particles were characterized by Fourier transform infrared, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and thermogravimetric analyses. Electron microscopy showed that the composite particles are doped with nanosized NiO.

Keywords: Inorganic-organic Composite, Epoxy Functionality, Seeded Copolymerization, NiO, Doping

Cite this paper: Mohammmad S. Hossan, Mohammad A. Rahman, Mohammad R. Karim, Mohammad A. J. Miah, Hasan Ahmad, Preparation of Epoxy Functionalized Hybrid Nickel Oxide Composite Polymer Particles, American Journal of Polymer Science, Vol. 3 No. 5, 2013, pp. 83-89. doi: 10.5923/j.ajps.20130305.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

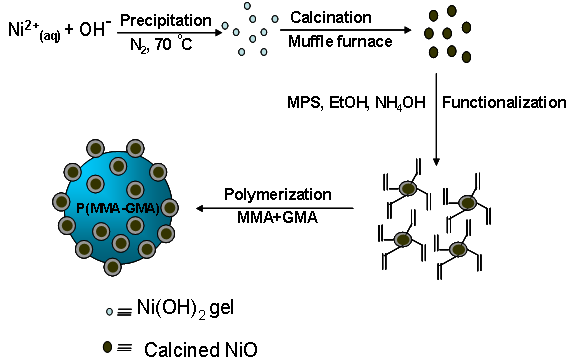

- Hybrid polymer composites are a class of materials that combine the properties of inorganic materials with the easy processability, flexibility, elasticity, lighter weight and improved colloidal stability of organic polymer particles. The fabrication of hybrid inorganic/organic polymer composites offers advantages especially when those applications depend on mechanical and surface properties. Now a day researchers are showing much interest on the preparation of hybrid polymer particles because one can enhance or even incorporate novel properties (e.g. mechanical, electrical, catalytic, rheological, magnetic and optical) by independently altering the composition, dimension and structure. These inorganic-organic hybrid polymer particles find wide application potentials in catalysis, electrical, optical and electronic or photonic devices, biomaterials, flame-retardant and coatings[1-9]. There is an increasing interest in the synthesis of nanosized metal oxides because of their large surface area unusual adsorptive properties, surface defects, fast diffusivities and quantum size effects which are different from those of bulk materials[10-15]. Metal (oxide) nano particles smaller than about 20 nm have received widespread interest recently because of their envisioned applications in electronics, optics, and magnetic storage devices. Among the various oxide materials, nickel oxide (NiO) is a very important semiconducting oxide material extensively used in catalysis, battery cathodes, gas sensors, electrochromic films, and magnetic materials[16–25]. NiO catalyst exhibits good low temperature catalytic performance for oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane to ethylene reaction[26]. In addition NiO has received considerable interest for its catalytic properties in decomposition of ammonium perchlorate,[27] hydrocracking reactions, reforming of hydrocarbons, and methane for production of synthesis gas, the removal of tar followed by the adjustment of the gas composition in biomass pyrolysis/gasification, in cellulose pyrolysis, and so forth[28]. These mechanical and physical properties as well as application potentials can be further improved by reducing the size and size distribution in the nano-range[29].Despite the wide application potential of hybrid NiO composite polymer particles in different industries only few reports are available on the designing of such polymer particles. López et al. reported the preparation of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)/NiO nanocomposites by in situ bulk polymerization[30]. Prior to this, they treated the NiO particles with silane coupling agent. In another research, polyaniline/NiO/sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate composite microspheres were synthesized in micelles by using ammonium peroxydisulfate initiator[31]. In an early work the author studied the feasibility of seeded emulsion polymerization to encapsulate NiO nano particles within PMMA shell layer using different NiO/MMA ratio (w/w)[32]. However, this results in some free NiO particles though the encapsulation efficiency was pretty good.In the present investigation attempt was made to prepare hybrid epoxy functional NiO/poly(MMA-glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)) composite polymer particles via seeded polymerization in presence of silane coupled functionalized NiO particles. The introduction of easily transformable epoxy group would give reactive starting material for the design of whole range of compounds with various functional groups. These groups can be employed directly or via modification using cationic, anionic, chelate-forming, or fluorescent routes for immobilization of biopolymers, dyes and other sensitive compounds[33-36]. Additionally PMMA has some interesting properties like exceptional optical transparency, good mechanical properties, good weatherability, acceptable thermal stability, moldability and easy shaping[30,37]. The preparation scheme of NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles are depicted in figure 1.

| Figure 1. Schematic representation for the preparation of NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles |

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

- MMA and GMA of monomer grade purchased from Fluka, Chemika, Switzerland were distilled under reduced pressure to remove inhibitors. Oil soluble initiator2,2'-azobis(isoobutyronirile) (AIBN) from LOBA Chem., India was recrystalized from methanol, vacuum dried at 5°C and preserved in the refrigerator before use. Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) of molecular weight 3.6 x 105 gmol-1 from Fluka, Chemika, Switzerland were used as a steric stabilizer. 3-(Methacryloyloxy)propyltriethoxysilane (MPS) from Alfa Aesar, UK, was used as a coupling agent. Ethanol was dehydrated and distilled before use. Other chemicals such as oleic acid, Ni(NO3)2.6H2O, NH4OH were of analytical grade. Deionized water was distilled using a glass (Pyrex) distillation apparatus.

2.2. Instruments

- Scanning electron microscope or SEM (LEO Electron Microscopy Ltd, Cambridge, UK) was used to see the morphology and particle size distribution. IR spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, FTIR-100, UK), proton NMR (JEOL spectrometer, 400 MHz, JNM-LA400, Japan) and table top high speed centrifuge machine (TG 16-WS, China) were used in this study. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the powder samples were taken on Scanning X-ray Diffractometer (D8 Bruker AXS) using Cu K-α- radiation (0.1542 nm) in parallel geometry (not focused). The intensities were measured at 2-theta values from 4.5° to 100° at a continuous scan rate of 10°/min with a position sensitive detector aperture at 3° (equivalent to 0.5°/min with a scintillator counter). Thermal analysis was carried out using a thermogravimetry analyser (TGA) from TGA Iris, TG 209 F1, Netzsch (Selb, Germany).

2.3. Preparation of Nanosized NiO Particles

- Aqueous solution (0.6 M) of Ni(NO3)2.6H2O was heated at 80°C, and the temperature was gradually increased to 100°C over 2 h under magnetic stirring. NH4OH was added slowly into the solution until pH 7 was reached. A green colloid solution was obtained, which was filtered and washed several times with deionized distilled water. The residual part was then dried at 100°C for 10 h to obtain the asprepared precursor, Ni(OH)2 powder. The powder was calcined in platinum crucible at 400°C for 3 h to obtain the nanosized NiO particles.

2.4. Functionalization of NiO Particles

- In order to improve the dispersibility, oleic acid stabilized NiO particles were prepared. First calculated amounts of NiO nano particles were dispersed in deionized distilled water by sonication for 1 h. Then 13 mL of oleic acid per unit mass of nano particles were added dropwise into the NiO nano particles dispersion at 80°C over the course of 2 h under vigorous magnetic stirring. The oleic acid stabilized NiO particles were washed repeatedly by serum replacement using water followed by ethanol to remove the excess oleic acid. 1.5 g of MPS per unit mass of oleic acid stabilized NiO particles was finally added and the dispersion was magnetically stirred at ambient temperature for 48 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. The MPS functionalized NiO particles were washed repeatedly by serum replacement using ethanol through repeated centrifugation.

2.5. Preparation of NiO/P(MMA-GMA) Composite Particles by Seeded Copolymerization

- 0.5 g of functionalized NiO particles dispersed in 50 g ethanol was taken in three necked round bottomed flask dipped in a thermostat water bath maintained at 70°C. 1.75 g of MMA and 0.75 g of GMA were added into the flask and 0.1 g of PVP was used as steric stabilizer. Polymerization was started by adding oil soluble AIBN (0.05 g) as initiator under a nitrogen atmosphere while the reaction was continued for 12 h. The produced composite particles were washed three times by serum replacement to remove any unreacted monomer and initiator fragments.

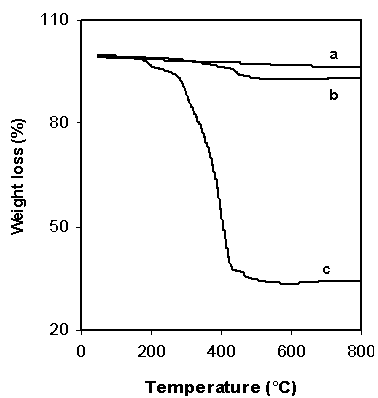

2.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

- Thermal properties of the dried powder were measured by heating samples under flowing nitrogen atmosphere from 20°C to 800°C at a heating rate of 5°C/min and the weight loss was recorded.

3. Results and Discussion

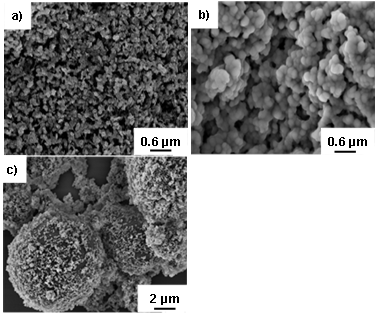

- SEM images of NiO, functionalized NiO and NiO/P (MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles are illustrated in figure 2. The average diameters of bare NiO particles are in the range of 30-70 nm and the average size of MPS modified NiO particles visibly increased to almost 200-300 nm. The increase in size is attributed to the functionalization of NiO particles by oleic acid and MPS. SEM image of NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles clearly shows deposition of smaller NiO particles on the surface of several micron-sized P(MMA-GMA) copolymer particles. From the image it is not clear whether some NiO particles are encapsulated within the polymer shell layer during seeded copolymerization though it was expected that presence of vinyl group in the silane coupling agent would favour copolymerization of MMA and GMA on the surface of functionalized NiO particles. The mechanism of formation of NiO doped composite particles is not yet clear. However, during seeded copolymerization in ethanol medium the prior formation of P(MMA-GMA) primary particles from secondary nucleation can’t be ruled out due to comparatively faster copolymerization reaction between MMA and GMA. As the concentration of MMA and GMA decreased towards the end of the copolymerization functionalized NiO particles participated in reaction through vinyl groups, resulted in NiO doped composite particles. It is also evident that NiO/ P(MMA-GMA) composite particles are bit polydispersed ranging from four to several microns. Some small clusters of free NiO particles not participated in seeded copolymerization are also visible.

| Figure 2. SEM photographs of NiO particles a), functionalized NiO particles b), and NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles c) |

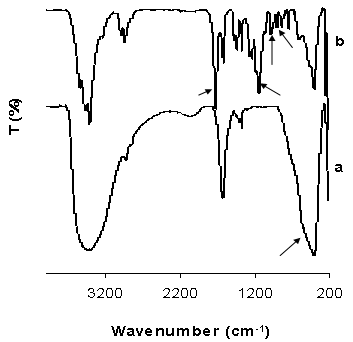

| Figure 3. FTIR spectra of functionalized NiO particles a) and NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles b) recorded in KBr pellets |

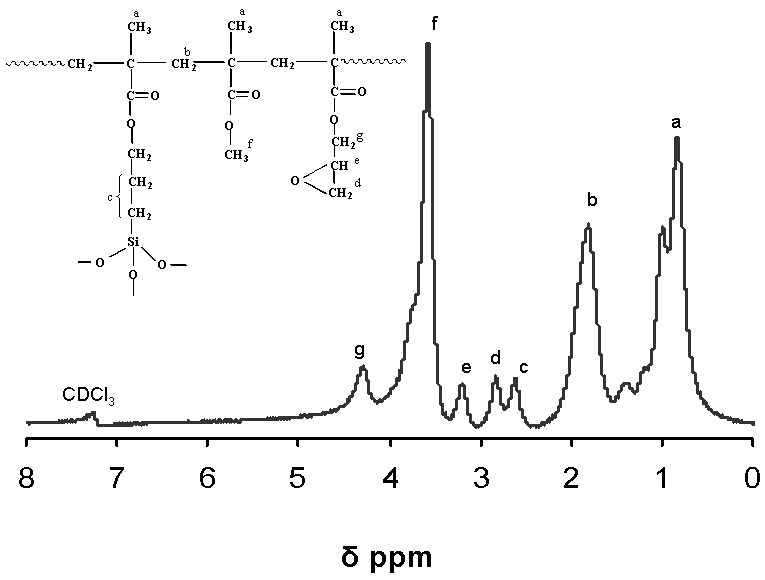

| Figure 4. 1H NMR spectra of NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles taken in CDCl3 |

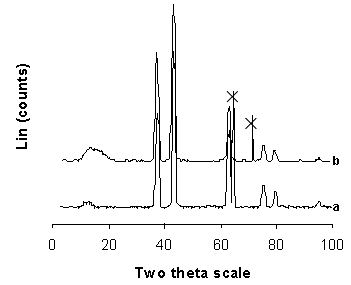

| Figure 5. X ray diffraction patterns (XRD) of functionalized NiO particles a) and NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles |

| Figure 6. TGA thermograms of unmodified NiO particles (reference material) a), functionalized NiO particles b), and NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite polymer particles |

4. Conclusions

- A simple three step process was attempted to prepare epoxy functional NiO hybrid composite polymer particles. The particles were named as NiO/P(MMA-GMA) composite particles. Nanosized NiO particles were first prepared by liquid-phase process. NiO particles were then functionalized with silane coupling agent and finally seeded copolymerization of MMA and GMA was carried out in ethanol media. NiO doped epoxy functional composite particles were obtained as confirmed by electron micrographs, FTIR, NMR, XRD and TGA analyses.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML