-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Mathematics and Statistics

p-ISSN: 2162-948X e-ISSN: 2162-8475

2016; 6(3): 115-121

doi:10.5923/j.ajms.20160603.05

Convergence of Binomial, Poisson, Negative-Binomial, and Gamma to Normal Distribution: Moment Generating Functions Technique

Subhash C. Bagui1, K. L. Mehra2

1Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of West Florida, Pensacola, USA

2Department of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, USA

Correspondence to: Subhash C. Bagui, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of West Florida, Pensacola, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In this article, we employ moment generating functions (mgf’s) of Binomial, Poisson, Negative-binomial and gamma distributions to demonstrate their convergence to normality as one of their parameters increases indefinitely. The motivation behind this work is to emphasize a direct use of mgf’s in the convergence proofs. These specific mgf proofs may not be all found together in a book or a single paper. Readers would find this article very informative and especially useful from the pedagogical stand point.

Keywords: Binomial distribution, Central limit theorem, Gamma distribution, Moment generating function, Negative-Binomial distribution, Poisson distribution

Cite this paper: Subhash C. Bagui, K. L. Mehra, Convergence of Binomial, Poisson, Negative-Binomial, and Gamma to Normal Distribution: Moment Generating Functions Technique, American Journal of Mathematics and Statistics, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 115-121. doi: 10.5923/j.ajms.20160603.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The basic Central Limit Theorem (CLT) tells us that, when appropriately normalised, sums of independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables (r.v.’s) from any distribution, with finite mean and variance, would have their distributions converge to normality, as the sample size n tends to infinity. If we accept this CLT and are in knowledge of the fact that Binomial, Poisson, Negative-binomial and Gamma r.v.’s are themselves sums of i.i.d. r.v.’s, we can conclude the limiting normality of these distributions by applying this CLT. We must note, however, that the proof of this CLT is based on the use of Characteristic Functions theory involving Complex Analysis, the study of which primarily only advanced math majors in colleges and universities undertake. There are available, indeed, other methods of proof in specific cases, e.g., in case of Binomial and Poisson distributions through approximations of probability mass functions (pmf) by the corresponding normal probability density function (pdf) using Stirling’s formula (cf., Stigler, S.M. 1986, pp.70-88, [8]; Bagui et al. 2013b, p. 115, [2]) or by simply approximating the ratios of successive pmf terms of the distribution one is dealing with (cf., Proschan, M.A. 2013, pp. 62-63, [6]). However, by using the parallel (to characteristic functions) methodology of mgf’s, which does not involve Complex Analysis, we can also accomplish the same objective with relative ease. This is what we propose to explicitly demonstrate in this paper. The structure of the paper is as follows. We provide some useful preliminary results in Section 2. These results will be used in section 3. In Section 3 we give all the details of convergence for all the above mentioned distributions to normal distribution. Section 4 contains some concluding remarks.

2. Preliminaries

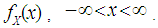

- In this section, we state some results that will be used in various proofs presented in section 3.Definition 2.1. Let

be a r.v. with probability mass function (pmf) or probability density function (pdf)

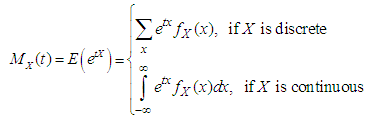

be a r.v. with probability mass function (pmf) or probability density function (pdf) Then the moment generating function (mgf) of the r.v.

Then the moment generating function (mgf) of the r.v.  is defined as

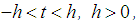

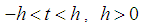

is defined as assume to exist and be finite for all

assume to exist and be finite for all  for an

for an  If

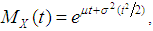

If  has a normal distribution with mean

has a normal distribution with mean  and variance

and variance  , then mgf of

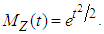

, then mgf of  is given by

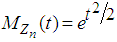

is given by  [3]. If

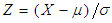

[3]. If  , then

, then  is said to have standard normal distribution (i.e., a normal distribution with mean zero and variance one). The mgf of

is said to have standard normal distribution (i.e., a normal distribution with mean zero and variance one). The mgf of  is given by

is given by  Let

Let  denote the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of the r.v.

denote the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of the r.v.  Theorem 2.1. Let

Theorem 2.1. Let  and

and  be two cumulative distribution functions (cdf’s) whose moments exist. If the mgf’s exist for the r.v.’s

be two cumulative distribution functions (cdf’s) whose moments exist. If the mgf’s exist for the r.v.’s  and

and  and

and  for all

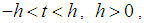

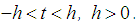

for all  in

in  then

then  for all

for all  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  for all

for all  A probability distribution is not always determined by its moments. Suppose

A probability distribution is not always determined by its moments. Suppose  has cdf

has cdf  and moments

and moments which exist for all

which exist for all  . If

. If  has a positive radius of convergence for all

has a positive radius of convergence for all  (Billingsley 1995, Section 30, [4]; Serfling 1980, p. 46, [7]), then mgf exists in the interval

(Billingsley 1995, Section 30, [4]; Serfling 1980, p. 46, [7]), then mgf exists in the interval  and hence uniquely determines the probability distribution.A weaker sufficient condition for the moment sequence to determine a probability distribution uniquely is

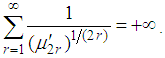

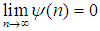

and hence uniquely determines the probability distribution.A weaker sufficient condition for the moment sequence to determine a probability distribution uniquely is  This sufficient condition is due to Carleman (Chung 1974, p. 82, [5]; Serfling 1980, p. 46, [7]). Theorem 2.2. Let

This sufficient condition is due to Carleman (Chung 1974, p. 82, [5]; Serfling 1980, p. 46, [7]). Theorem 2.2. Let  be a sequence of r.v’s with the corresponding mgf sequence as

be a sequence of r.v’s with the corresponding mgf sequence as

and

and  be a r.v. with mgf

be a r.v. with mgf  which are assumed exist for all

which are assumed exist for all  If

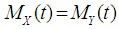

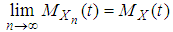

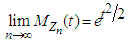

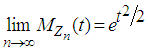

If  for

for  , then

, then  The notation

The notation  means that, as

means that, as  the distribution of the r.v.

the distribution of the r.v.  converges to the distribution of the r.v.

converges to the distribution of the r.v.  Lemma 2.1. Let

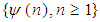

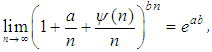

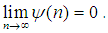

Lemma 2.1. Let  be a sequence of reals. Then,

be a sequence of reals. Then,  provided

provided  and

and  do not depend on

do not depend on  an

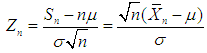

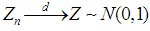

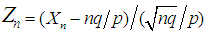

an  CLT (See Bagui et al. 2013a, [1]). Let

CLT (See Bagui et al. 2013a, [1]). Let  be a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with mean

be a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with mean  ,

,  , and variance

, and variance  ,

,  , and set

, and set

and

and  .Then

.Then  , as

, as  , where

, where  stands for a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1.For Definition 2.1, Theorem 2.1, Theorem 2.2, and Lemma 2.1, see Casella and Berger, 2002, pp. 62-66, [4] and Bain and Engelhardt, 1992, p. 234, [3].

stands for a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1.For Definition 2.1, Theorem 2.1, Theorem 2.2, and Lemma 2.1, see Casella and Berger, 2002, pp. 62-66, [4] and Bain and Engelhardt, 1992, p. 234, [3]. 3. Congergence of Mgf’s

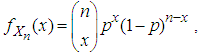

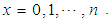

3.1. Binomial

- Binomial probabilities apply to situations involving a series of

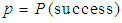

independent and identical trials with two possible outcomes –a success with probability

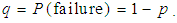

independent and identical trials with two possible outcomes –a success with probability  and a failure with probability

and a failure with probability  - on each trial. Let

- on each trial. Let  be the number of successes in

be the number of successes in  trials, then

trials, then  has binomial distribution with parameters

has binomial distribution with parameters  and

and  . The probability mass function of

. The probability mass function of  is given by

is given by

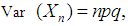

Thus the mean of

Thus the mean of  is

is  and the variance of

and the variance of  is

is

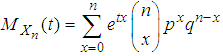

The mgf of

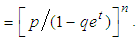

The mgf of  is given by

is given by

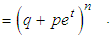

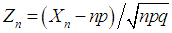

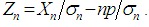

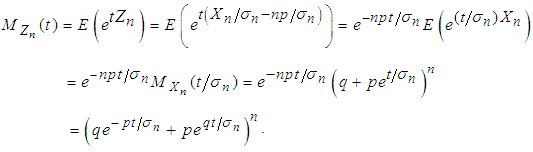

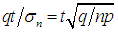

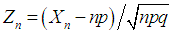

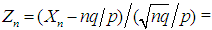

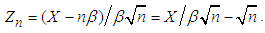

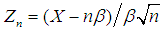

Let

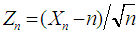

Let  . With simplified notation

. With simplified notation we have

we have  Below we derive the mgf of

Below we derive the mgf of  Now the mgf of

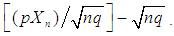

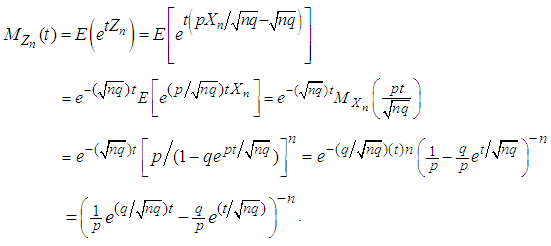

Now the mgf of  is given by

is given by | (3.1) |

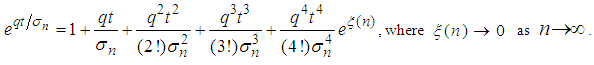

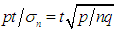

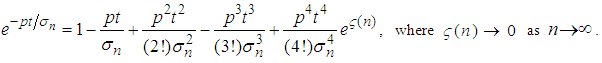

between 0 and

between 0 and  such that

such that | (3.2) |

between 0 and

between 0 and  such that

such that | (3.3) |

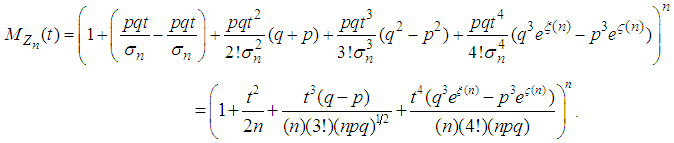

in (3.1), we have

in (3.1), we have | (3.4) |

Since

Since  as

as  then

then  for every fixed value of

for every fixed value of  Thus based on Lemma 2.1 we have

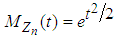

Thus based on Lemma 2.1 we have for all real values of

for all real values of  That is, in view of Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we conclude that the r.v.

That is, in view of Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we conclude that the r.v.  has the limiting standard normal distribution. Consequently, the binomial r.v.

has the limiting standard normal distribution. Consequently, the binomial r.v.  has, for large

has, for large  an approximate normal distribution with mean

an approximate normal distribution with mean  and variance

and variance

3.2. Poisson

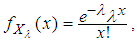

- The Poisson distribution is appropriate for predicting rare events within a certain period of time. Let

be a Poisson r.v. with parameter

be a Poisson r.v. with parameter  The probability mass function of

The probability mass function of  is given by

is given by

Both the mean and variance of

Both the mean and variance of  are

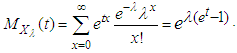

are  The mgf of

The mgf of  is given by

is given by  For notational convenience let

For notational convenience let  and

and

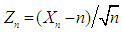

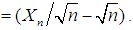

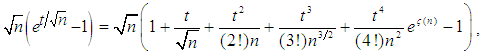

Below we derive the mgf of

Below we derive the mgf of  which is given by

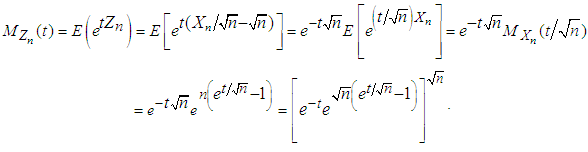

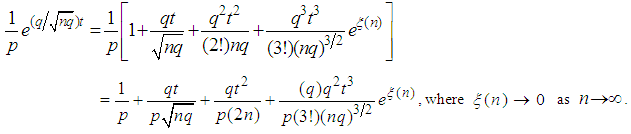

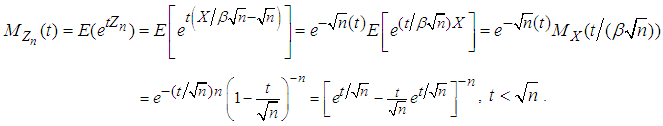

which is given by | (3.5) |

as

as  where

where  is number between

is number between  and

and  and converges to zero as

and converges to zero as  Further the above term

Further the above term  may be simplified as

may be simplified as

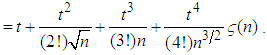

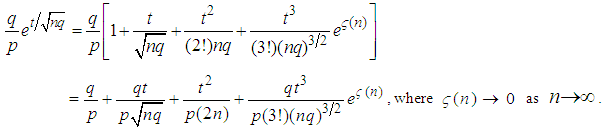

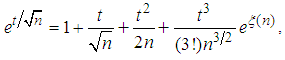

Now substituting this in the last expression (3.5) for

Now substituting this in the last expression (3.5) for we have

we have where

where  which tends to

which tends to  as

as  . Hence, we have

. Hence, we have  for all real values of

for all real values of  Using Theorems 2.1 and 2.2 we conclude that

Using Theorems 2.1 and 2.2 we conclude that  has the limiting standard normal distribution. Hence, the Poisson r.v.

has the limiting standard normal distribution. Hence, the Poisson r.v.  has also an approximate normal distribution with both mean and variance equal to

has also an approximate normal distribution with both mean and variance equal to  for large

for large

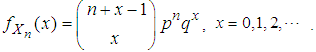

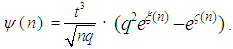

3.3. Negative Binomial

- Consider an infinite series of independent trials, each having two possible outcomes, success or failure. Let

and

and  Define the random variable

Define the random variable  to be the number of failures before the

to be the number of failures before the  success. Then

success. Then  has negative binomial distribution with parameters

has negative binomial distribution with parameters  and

and  . Thus, the probability mass function of

. Thus, the probability mass function of  is given by

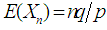

is given by  The mean of

The mean of  is given by

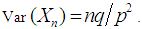

is given by  and the variance of

and the variance of  is given by

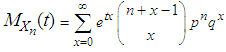

is given by  The mgf of

The mgf of  can be obtained as

can be obtained as

Let

Let

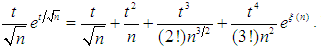

Now the mgf of

Now the mgf of  is given by

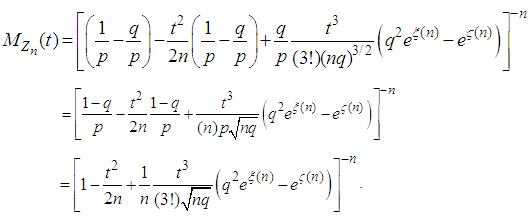

is given by | (3.6) |

between

between  and

and  such that

such that | (3.7) |

between

between  and

and  such that

such that | (3.8) |

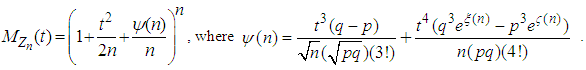

in (3.6), we have

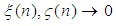

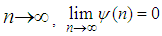

in (3.6), we have  | (3.9) |

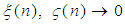

where

where  Since both

Since both  as

as  for every fixed value of

for every fixed value of  Hence by lemma 2.1 we have

Hence by lemma 2.1 we have for all real values of

for all real values of  Hence, by Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we conclude the r.v.

Hence, by Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we conclude the r.v.  has the limiting standard normal distribution. Accordingly, the negative-Binomial r.v.

has the limiting standard normal distribution. Accordingly, the negative-Binomial r.v.  has approximately a normal distribution with mean

has approximately a normal distribution with mean  and variance

and variance  for large

for large

3.4. Gamma

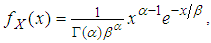

- The Gamma distribution is appropriate for modeling waiting times for events. Let

be a Gamma r.v. with pdf

be a Gamma r.v. with pdf

and

and  The

The  is called the shape parameter of the distribution and

is called the shape parameter of the distribution and  is called the scale parameter of the distribution. For convenience let us denote

is called the scale parameter of the distribution. For convenience let us denote  by

by  It is well known that the mean of

It is well known that the mean of  is

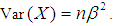

is  and the variance of

and the variance of  is

is  The mgf of

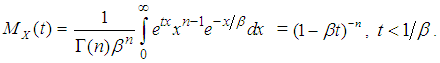

The mgf of  is given by

is given by  Let

Let  The mgf of

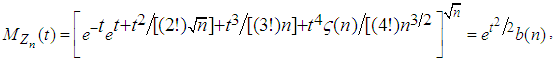

The mgf of  is given by

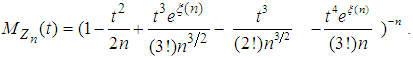

is given by | (3.10) |

where

where  is a number between

is a number between  and

and  and tends to zero as

and tends to zero as  and

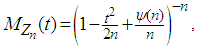

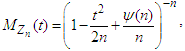

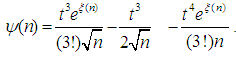

and  Now substituting these two in the last expression of

Now substituting these two in the last expression of  in (3.10), we have

in (3.10), we have  This can be written as

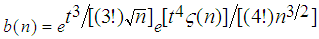

This can be written as  where

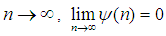

where  Since

Since  as

as  for every fixed value of

for every fixed value of  Hence by Lemma 2.1 we have

Hence by Lemma 2.1 we have for all real values of

for all real values of  Hence, by Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we conclude the r.v.

Hence, by Theorems 2.1 and 2.2, we conclude the r.v.  has the limiting standard normal distribution. Accordingly, the Gamma r.v. has approximately a normal distribution with mean

has the limiting standard normal distribution. Accordingly, the Gamma r.v. has approximately a normal distribution with mean  and varianc

and varianc  for large

for large

4. Concluding Remarks

- It is well-known that a Binomial r.v. is the sum of i.i.d. Bernouli r.v.’s, a Poisson

r.v., with

r.v., with  a positive integer, the sum of

a positive integer, the sum of  i.i.d.

i.i.d.  r. v.’s, a Negative-binomial r.v. the sum of i.i.d. geometric r.v.’s and a Gamma r.v. the sum of i.i.d. exponential r.v.’s. In view of these facts, one can easily conclude by applying the above stated general CLT that the above distributions, after proper normalizations, converge to a normal distribution as

r. v.’s, a Negative-binomial r.v. the sum of i.i.d. geometric r.v.’s and a Gamma r.v. the sum of i.i.d. exponential r.v.’s. In view of these facts, one can easily conclude by applying the above stated general CLT that the above distributions, after proper normalizations, converge to a normal distribution as  the number of terms in their respective sums, increases to infinity. But these facts may be beyond the knowledge of undergraduate students, especially those who are non-math majors. However, as demonstrated in the preceding Section 3 for the Binomial, Poisson, Negative-binomial and Gamma distributions, in dealing with distributional convergence problems where individual mgf’s exist and are available, we can use the mgf technique effectively to formally deduce their limiting distributions. In our view, this latter technique is natural, equally instructive and at a more manageable level. In any case, it provides an alternative approach.In the proof of general central limit theorem using mgf both Bain and Engelhardt (1992), [3] and Inlow (2010), [6a] use the mgf of sum of i.i.d r.v’s. But we are using the existing mgf of all the above mentioned distributions without treating them as sums of i.i.d. r.v.’s. Bain and Engelhardt (1992), [3] discusses a proof of convergence of binomial to normal using mgf. But this paper formalizes mgf proofs of collection of distributions. The paper framed in this way can serve as an excellent teaching reference. The proofs are straightforward and require only an additional knowledge of Taylor series expansion, beyond the skills to handle algebraic equations and basic probabilistic concepts. The material should be of pedagogical interest, and can be discussed in classes where only basic calculus and skills to deal with algebraic expressions are the only background requirements. The article should also be of reading interest for senior undergraduate students in probability and statistics.

the number of terms in their respective sums, increases to infinity. But these facts may be beyond the knowledge of undergraduate students, especially those who are non-math majors. However, as demonstrated in the preceding Section 3 for the Binomial, Poisson, Negative-binomial and Gamma distributions, in dealing with distributional convergence problems where individual mgf’s exist and are available, we can use the mgf technique effectively to formally deduce their limiting distributions. In our view, this latter technique is natural, equally instructive and at a more manageable level. In any case, it provides an alternative approach.In the proof of general central limit theorem using mgf both Bain and Engelhardt (1992), [3] and Inlow (2010), [6a] use the mgf of sum of i.i.d r.v’s. But we are using the existing mgf of all the above mentioned distributions without treating them as sums of i.i.d. r.v.’s. Bain and Engelhardt (1992), [3] discusses a proof of convergence of binomial to normal using mgf. But this paper formalizes mgf proofs of collection of distributions. The paper framed in this way can serve as an excellent teaching reference. The proofs are straightforward and require only an additional knowledge of Taylor series expansion, beyond the skills to handle algebraic equations and basic probabilistic concepts. The material should be of pedagogical interest, and can be discussed in classes where only basic calculus and skills to deal with algebraic expressions are the only background requirements. The article should also be of reading interest for senior undergraduate students in probability and statistics.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are thankful to the Editor-in-Chief and an anonymous referee for their careful reading of the paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML