-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Mathematics and Statistics

p-ISSN: 2162-948X e-ISSN: 2162-8475

2016; 6(2): 71-78

doi:10.5923/j.ajms.20160602.01

A Random Effect Logistic Regression Model of Major Depressive Disorder among Ageing Nigerians

O. P. Idowu1, O. B. Yusuf1, O. M. Akpa1, O. Gureje2

1Department Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

2Department of Psychiatry, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Correspondence to: O. B. Yusuf, Department Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a major public health problem in Nigeria and has severely devastating effects on the elderly. Previous studies on MDD among elderly Nigerians have utilized cross sectional designs which are descriptive in nature and have not investigated differences in setting and time-occurrence of MDD. Therefore this study employed a random effect logistic regression model to determine the relative effects/contributions of individual and environmental factors in the occurrence of MDD. A secondary analysis of a four-year longitudinal data from the Ibadan Study of Ageing was conducted. A total of 2,149 elderly Nigerians participated in the study between 2003 and 2009. The Geriatric Depression Scale was used to assess MDD and consequently classified as “present” for scores ranging from 10 to 30 and “absent” for scores ranging from 0 to 9. A random effect logistic regression model was fitted to determine factors predicting MDD. Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals, and Intra-class Correlation Coefficients (ICC) for each random effect was estimated. The overall prevalence of MDD was 27.28%. Significant predictors of MDD included “no-contact with family members” (OR=2.9, 95%CI: 1.26-6.70), “no-contact with friends” (OR=1.32, 95%CI: 1.05-1.67)), non-participation in family activities (OR=2.07, 95%CI: 1.63-2.43), non-participation in community activities (OR=1.93, 95%CI: 1.54-2.43), and good quality of health (OR=0.25, 95%CI: 0.15-0.27). Disparities in the occurrence of MDD among the elderly were attributable to enumeration areas (6%) and the individuals (22%). Social isolation factors and self-reported quality of health are significant predictors of MDD among elderly Nigerians.

Keywords: Random Effect, Logistic Regression, Major Depressive Disorder, Elderly Nigerians

Cite this paper: O. P. Idowu, O. B. Yusuf, O. M. Akpa, O. Gureje, A Random Effect Logistic Regression Model of Major Depressive Disorder among Ageing Nigerians, American Journal of Mathematics and Statistics, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 71-78. doi: 10.5923/j.ajms.20160602.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Depression, a common but serious mental disorder, occurs worldwide across all age groups. Globally, it affects approximately 350 million people as at 2012, making it one of the leading causes of disability among the elderly [1]. It is also one of the 10 major diseases projected to cause the most disability-adjusted life years in low-income countries by the year 2030 [2]. Even though, depression is preventable [3-5], elderly people are faced with this mental illness [2].Past studies have shown that Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a major public health problem in Nigeria [6, 7] and has severely devastating effects [8] on the elderly. It is characterized by a combination of symptoms such as worthlessness, and restlessness that undermines the patient’s ability to engage in normal daily living [9]. Consequently, living with untreated MDD is a serious public health problem as it is a major cause of death, family disconnection, emotional burden etc. In fact, it is not uncommon that MDD patients often commit suicide [10]. MDD is associated with considerable morbidity and co-morbidity and the cost of treatment of somatic illnesses, such as diabetes [11] are considerably higher for MDD patients.Prevalence of depression varies by setting and screening/diagnostic tools. Previous studies on MDD among the elderly in Nigeria have reported prevalence rates as high as 28% in eastern Nigeria [12] using the Geriatric Depression Scale; and as low as 7·1% observed from the baseline analysis of the Ibadan Study of Ageing (ISA), in which the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria was employed [7]. However, a prevalence as high as 63% was observed in Korea [13], using the Korean version of the short form of Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS-K). A study among individuals aged 50 years or above in South Africa reported a prevalence as low as 4.0% [14]. In Thailand, the prevalence of depression using the Thai validated Euro-D scale among elderly respondents living in Kanchanaburi was 28.5% [15].Predictors of MDD among the elderly as identified by many studies cut across factors such as social, demographic, economic, lifestyle and health factors; nonetheless, data on the African population remain scarce. Female sex and increasing levels of urbanisation are associated with MDD among the elderly [7, 12, 16]. Also, older age groups, poor family support, marital disharmony, widowhood, bereavement, poor/low educational background and low social status (poverty) were found to be risk factors for depressive illness in the elderly [12, 16, 17]. Whereas, in Thailand, it was identified that infirmity, disability and serious life events were the three major predictors of depression for older people [15]. However, unlike most studies above mentioned, excluding the fact that functional disability, lack of quality of life, and chronic conditions (angina, asthma, arthritis, and nocturnal sleep problems) were associated with depression, no significant socio-economic (gender, population group, socio-economic status, geo-locality), behaviour (dietary habits, physical activity), and cognitive impairment differences in relation to depression prevalence was found in South Africa [14]. Previous studies on MDD among elderly people in Nigeria and Africa at large have utilized cross sectional designs which are descriptive in nature and have not investigated differences in settings and time-occurrence of MDD. However, this is important owing to the fact that the problem of MDD among the elderly is often worsened by environmental factors [12] and its effects on them is severely devastating [8] as they increase with age. In this study, we employed a random effect logistic regression model to determine the relative effects/contributions of individual and environmental factors in the occurrence of MDD.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- The present study was an analysis of data from the Ibadan Study of Ageing (ISA), a community-based longitudinal survey, conducted in eight states in the south-western and north-central regions in Nigeria (Lagos, Ogun, Osun, Oyo, Ondo, Ekiti, Kogi and Kwara) over a four year period (2003/2004, 2007-2009). These states as at the time of baseline (2003/2004) accounted for about 22% of the Nigerian population (approximately, 25 million people). Participants were elderly people aged 65 years or above who resided in the aforementioned states. Among them, only those residing in households and fluent in Yoruba, the language of study were recruited.

2.2. Instruments

- The questionnaire contained socio-demographic, social engagement and health characteristics. It was translated into Yoruba with iterative back-translation methods.Major Depressive Disorder at baseline and follow-up was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), a scale first developed in 1982 [18]. The scale is a well validated instrument. It was found to have 92% sensitivity and 89% specificity when evaluated against other diagnostic criteria [18] such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRS-D) and the Zung Self Rated Depression Scale (SDS). The GDS is a commonly used instrument for the assessment of depression among the elderly owing to its simplicity. It comprises 30-itemized questions which are simply answered: yes/no. A cumulative score of depression, for each participant, was obtained by assigning 1 to each response indicating depression and 0 otherwise. Cumulative scores within the range of 0 - 9, 10 - 19 and 20 - 30 are considered ‘Normal’, ‘Moderate depression’ and ‘Severe depression’ respectively [18]. For the purpose of this study depression was classified as “present” for scores in the range of 10 – 30 and “absent” for scores in the range of 0 – 9 [12].Social networks/engagement variables were assessed using items from the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3 (CIDI.3), [19]. The CIDI.3 enquires about the frequency of respondents’ Regular Family Contacts, Regular Friends Contacts, Involvement in Family Activities, and Involvement in Community Activities. The adapted CIDI items are as follows:● Regular Family Contacts: How often are you in contact with any members of your family who do not live with you -- including visits, phone calls, letters, or electronic mail messages?● Regular Friends Contacts: How often are you in contact with any of your friends?● Involvement in Family Activities: During the last 30 days, how much did you join in family activities, such as: eating together, talking with family members, visiting family members, working together? ● Involvement in Community Activities: During the last 30 days, how much did you join in community activities, such as: festivities, religious activities, talking with community members, working together? Responses from these questions were however dichotomized in this report as ‘NO’-no contacts/ involvements at all versus ‘Yes’-contacts/involvements varying from less than one per month/a little to daily/a lot.At each visit, participants reported if they had any Chronic Medical Condition such as asthma, tuberculosis, chronic arthritis, stroke, diabetes, chronic lung disease, hypertension, or cancer. They also gave a Self-Reported Quality of Health by answering the question: “How would you describe your overall health today?” which was rated as ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

2.3. Procedures

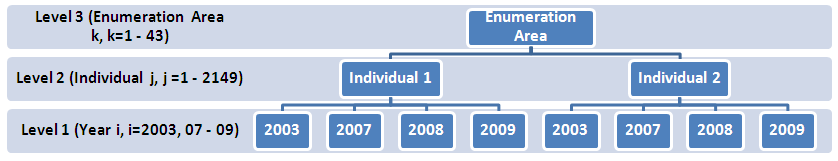

- A multistage cluster sampling of households within enumeration areas (geographical units demarcated by the National Population Commission) within each state was employed. Only one respondent, who had provided consent, mostly verbal due to illiteracy or by choice, was selected per household [6, 7]. But, whenever there was more than one person eligible for the study in a household, the Kish table selection method [20] was used for selection with no replacement for refusals. Thus, face-to-face interviews were successfully done at baseline with 2152 of 2908 respondents (of which 2149 were complete), giving a response rate of 74.2%. Respondents were subsequently followed up yearly from 2007 to 2009. The data was structured in a three-level hierarchical form (Figure 1). There were four years repeated measurement (units i / level 1) for each of the 2149 participants (clusters j / level 2) who were themselves clustered in 43 enumeration areas (super-clusters k / level 3).

| Figure 1. Hierarchical Structure of the data |

2.4. Data Analysis

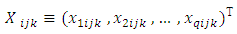

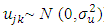

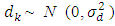

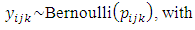

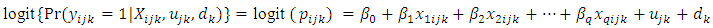

- The point prevalence and proportions of elderly with major depressive disorder by selected factors was presented in frequency tables. A three-level random effects logistic regression model was fitted using STATA version 12 [21].Let

represents MDD – the dependent variable and

represents MDD – the dependent variable and  is a vector containing Q fixed effect predictors such as place of residence, Age, Sex, etc. Identity Number (represented by

is a vector containing Q fixed effect predictors such as place of residence, Age, Sex, etc. Identity Number (represented by  ), and Enumeration Area (represented by

), and Enumeration Area (represented by  ) are random intercepts which were assumed to be independent of each other. In other words it is assumed that there is a random heterogeneity in the participants’ and enumeration areas’ underlying risk of MDD that persists throughout the entire duration of the study.Four models were estimated. The first model was a null (with no fixed effect variable) random-intercept model (model 0) serving as baseline model for comparing other models. The second model (model 1) included all fixed effects variables at level 1 i.e. age, marital group status, etc. In the third model (model 2), model 1 was adjusted for the fixed effect variable at level 2 i.e. sex and this helped to investigate the extent to which sex influenced the prediction of MDD over the years. Lastly, in the final (full) model (model 3), model 2 was adjusted for the fixed effect variable at level 3 i.e. site of residence and this allowed to assess the extent to which place of residence influenced the prediction of MDD.The final model is given by:

) are random intercepts which were assumed to be independent of each other. In other words it is assumed that there is a random heterogeneity in the participants’ and enumeration areas’ underlying risk of MDD that persists throughout the entire duration of the study.Four models were estimated. The first model was a null (with no fixed effect variable) random-intercept model (model 0) serving as baseline model for comparing other models. The second model (model 1) included all fixed effects variables at level 1 i.e. age, marital group status, etc. In the third model (model 2), model 1 was adjusted for the fixed effect variable at level 2 i.e. sex and this helped to investigate the extent to which sex influenced the prediction of MDD over the years. Lastly, in the final (full) model (model 3), model 2 was adjusted for the fixed effect variable at level 3 i.e. site of residence and this allowed to assess the extent to which place of residence influenced the prediction of MDD.The final model is given by:

| (1) |

is allowed to vary, throughout the entire duration of the study, over individuals

is allowed to vary, throughout the entire duration of the study, over individuals  and enumeration areas

and enumeration areas  with controlling fixed effect factors and covariates

with controlling fixed effect factors and covariates  The results of the fixed part of the estimated models were expressed as odds ratios (OR) together with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI); while the random part was expressed as Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for each random effect. ICC was obtained based on the linear threshold method which converts Level 1 variance into

The results of the fixed part of the estimated models were expressed as odds ratios (OR) together with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI); while the random part was expressed as Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for each random effect. ICC was obtained based on the linear threshold method which converts Level 1 variance into  (the logistic scale) on which Individual (level 2) variance

(the logistic scale) on which Individual (level 2) variance  and Enumeration Area (Level 3) variance

and Enumeration Area (Level 3) variance  are expressed [22]. The deviance statistic -2Log Likelihood (-2LL) test was used to determine which of the models best fit the data; on the assumption that the model with the least -2LL best fit the data. All analyses were performed at 5% level of significance.

are expressed [22]. The deviance statistic -2Log Likelihood (-2LL) test was used to determine which of the models best fit the data; on the assumption that the model with the least -2LL best fit the data. All analyses were performed at 5% level of significance. 3. Results

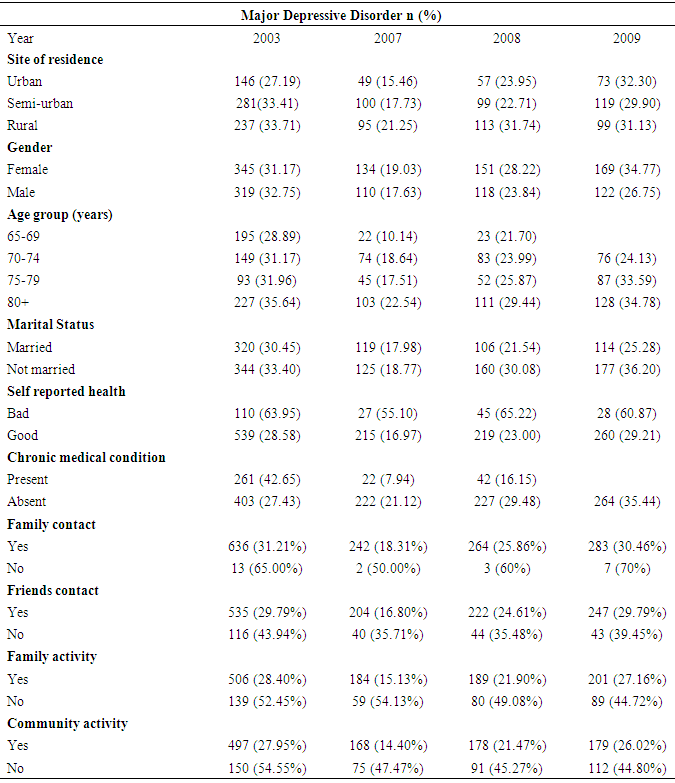

3.1. Prevalence

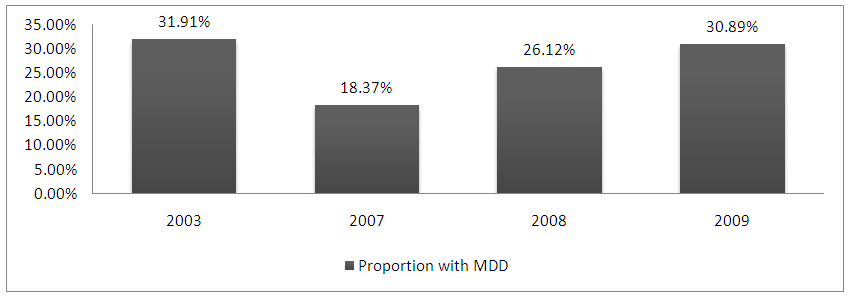

- At baseline, 555 (25.8%) of the 2,149 baseline study participants lived in urban areas and 53.8% were females. Seven hundred and twelve participants (31.1%) were in the 65-69 years age group while 648 (30.2%) participants were at least 80 years old.The number of participants with complete records decreased from 2,081 in 2003 to 942 in 2009. Figure 2 showed that the lowest prevalence of MDD was recorded in 2007 (18.4%) while the highest was in 2003 (31.91%), thus the overall MDD prevalence was 27.3%.

| Figure 2. Proportion of elderly Nigerians with MDD by year |

|

|

3.2. Random Effects Logistic Regression Analysis

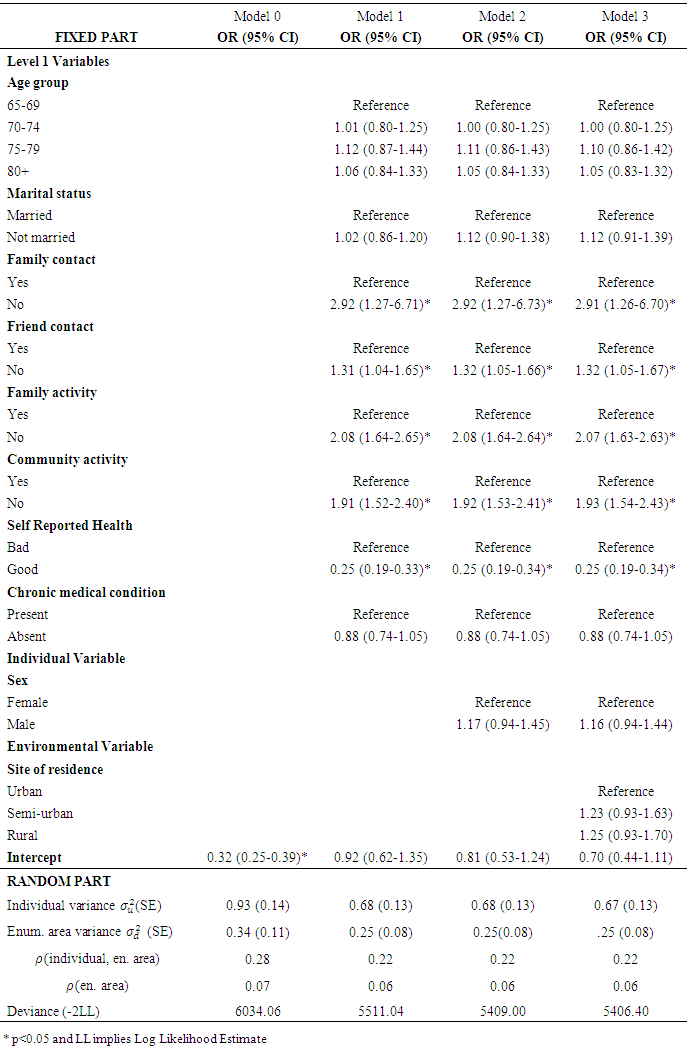

- Results for multivariate analyses revealed that there was no statistically significant association between MDD and factors such as: age, marital status and chronic medical condition. However, there was a statistically significant positive association between MDD and factors such as: regular family contact, regular friends contact, participation in family activity, participation in community activity and self-reported quality of health. Respondents who did not keep regular contact with family members were 3 times more likely to report MDD compared to respondents (belonging to the same enumeration area) who kept regular family contact (OR=2.92, 95% CI: 1.27-6.71). Respondents who did not keep regular contact with friends were more likely to report MDD compared to respondents (belonging to the same enumeration area) who kept regular contact with friends (OR=1.31, 95% CI: 1.04-1.65). Respondents who did not participate in family activity were 2 times more likely to report MDD compared to respondents (belonging to the same enumeration area) who participated in family activity (OR=2.08, 95%CI: 1.64-2.65).In the same manner, respondents with no participation in community activity were 2 times more likely to report MDD compared to respondents (belonging to the same enumeration area) who participated in community activity (OR=1.91, 95%CI: 1.52-2.40). Furthermore, respondents who perceived that their quality of health was good were 4 times less likely to be diagnosed of MDD compared to respondents (belonging to the same enumeration area) who reported poor quality of health (OR=0.25, 95%CI: 0.19-0.33). Compared to the empty model (model 0), the differences in the occurrence of MDD among the elderly were attributable to differences between enumeration areas (6%) and individuals (22%).Controlling for sex, the pattern of association remained the same in model 1. However, sex was not found to be significantly associated with MDD. Also, the variances at both individual and area levels in this model were similar to those observed in model 1. This suggested that sex did not improve the overall explained variance in the occurrence of MDD among the elderly compared to model 1.Moreover, after adjusting for place of residence in model 3 the pattern of association remained the same in model 2. However, place of residence was not found to be significantly associated with MDD. The variances at both individual and area levels in this model were similar to those observed in model 2. This also suggested that place of residence did not improve the overall explained variance in the occurrence of MDD among the elderly compared to model 2. Lastly, the smaller value 5406.40 of the deviance (-2LL) indicated that the full model (model 3) fitted the data better than models 1 and 2.

4. Discussion

- The overall prevalence of MDD among the elderly living in the Yoruba-speaking states of Nigeria was high. We observed that the prevalence of MDD was highest at baseline (2003), dropped to its lowest point in 2007, increased in 2008 and further increased in 2009. The steep drop in the prevalence of MDD between 2003 and 2007 might be as a result of a substantial attrition that occurred [23]. While the rise in the prevalence of MDD in the elderly after 2007 could be explained by its associated recurrence and chronic nature [23]. Compared to studies in which the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was also used, our overall estimate of the prevalence of MDD was analogous to the prevalence of MDD observed in an earlier study [12] in eastern Nigeria (28%) but lower than the 63% observed among elderly people in Korea [13]. Conversely, relatively low prevalence of MDD, among the elderly, was observed in South Africa (4%) [14] and the 7.1% from the baseline of the ISA in Nigeria [7]. This dissimilarity in prevalence may be as a result of the very high sensitivity of the GDS [18] as a screening instrument. It is important to note here that screening instruments, even though advocated to improve detection of depression, do not constitute diagnosis as they do not improve detection rates, treatment, or outcome [24, 25]. This high rate of MDD among elderly Nigerians could be explained by various factors especially those related to difficulties in receiving proper care. It is a known fact that elderly people and the society as well usually stigmatize against depression, and consider it as a weakness and personality defect [26]. Thus, depressed elderly are often hesitant to seek medical support from mental health specialists. Moreover, in settings like ours, there is no old age-targeted free (financial or structural) access measures to care coupled with dearth in effective health service provision for older persons [27]. For instance, in many developing countries [28], including Nigeria [27], in addition to limited treatment options, professional mental health services are unusual in rural areas with very few ones in semi-urban areas, and as a result diagnosis and management of depression is mostly the responsibility of primary health care clinicians [29]. Another reason for this high prevalence could be that of the harsh social and economic situation in Nigeria [7] which is especially harmful for elderly people as they have limited personal resources to help them survive in the society. This study also determined and accounted for both area and individual factors predicting MDD among ageing Nigerians. The results revealed that the differences in the high prevalence of MDD among the elderly were attributable to significantly high differences between enumeration areas. In other words enumeration areas played a significant role in the occurrence of MDD among the elderly throughout the study periods. Most studies on MDD among the elderly in this setting have not thoroughly investigated the effects of the environment/community of participants on their health outcome, thus interventions on its prevention and treatment are usually focused on the individual rather than using a community based approach. As a result, only a few individuals who have the capacity to access health facilities are provided with treatment. In fact, earlier studies in Nigeria have reported that only a minority of elderly persons living with MDD, in Nigeria, receive any treatment [6, 7]; hence MDD is becoming a major public health challenge.Previous studies [7, 12, 23] have reported that female sex was a risk factor for depression. However, in this study, we found out that female sex was not a risk factor for depression. This result is consistent with findings among patients in a Nigerian family practice population study [17]. A possible explanation for this non association could be due to the fact that there were more females than males throughout the study period, with the percentage of depressed subjects across gender being to a certain extent similar [17].Though, studies conducted elsewhere [23] have reported chronic medical condition as a predictor of MDD, our findings were contrary to this. Our finding is however similar to a previous report from this same setting [23]. Notwithstanding, it is not occasional that MDD often co-exists with somatic illnesses such as hypertension, chronic pain and diabetes as in the case of this sample of elderly Nigerians. Moreover, the severely devastating effects of depression [8] and other chronic medical conditions among this cohort of elderly likely had a huge effect on their self-reported perception of quality of health. Hence, it was not surprising that a higher rate of occurrence of MDD was observed among respondents who perceived that their quality of health was poor. An indirect reason for this observation may be owed to the fact that MDD remains under-recognized and under-treated in older patients with multiple medical problems [30]. Furthermore, a similar finding has been observed [13] among elderly Koreans. It was observed that perceived health status alone accounted for 17.3% of depression, and after adjusting for hand-grip strength and social activities, it increased to 22.6% and 25.2% respectively [13]. Consequently, it should be of benefit to elderly people to always hold a good perception of their own quality of health as it was found to be protective against MDD, in this study.Also, evidence-based programmes [31] such as: (1) IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment), (2) PEARLS (Program to Encourage Active Rewarding Lives for Seniors), (3) Healthy IDEAS (Identifying Depression, Empowering Activities for Seniors) could play a major role for the prompt diagnosis and treatment of MDD and co-occurring illnesses so as to quickly relieve patients from the unnecessary burdens of MDD in old age. A unique selling point about these programmes is that they use a collaborative (team-based) care management approach in identifying and treating depression among the elderly so as to improve low rates of treatment. These programmes are useful and could be easily adapted in our setting by following similar approach in the detection and management of elderly people living with MDD in Nigeria.We are however aware that our assessment of chronic health conditions may have been affected by false negatives owing the fact it is based on self-report. To that extent our report might be conservative rather than otherwise. For instance some participants with conditions such as diabetes and hypertension might not be conscious of being so afflicted.Furthermore, it was observed that elderly Nigerians who isolated themselves from their family members, friends and immediate community were more likely to report MDD. This could be as a result of declining traditional supportive network which is a direct consequence of rapid social changes experienced by the elderly in our setting [7, 23]. This finding confirms previous report that social factors were important risk factors for incident depression [29]. Another previous study, in California (USA) revealed that social isolation was a significant correlate of depression [16] among the elderly.

5. Conclusions

- Our findings suggest that depression among the elderly in Nigeria is high. Social isolation and self-reported health are significant predictors of MDD. Our finding points to the fact that incident MDD among older adults may be better addressed through community approaches such as community awareness and evidence-based community programmes in identifying and treating MDD. There is therefore a need for immediate public health approaches in identifying and treating elderly people living with depression in Nigeria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The Ibadan Study of Ageing was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust. We thank the study team. We also appreciate Mrs Oluwatoyin Bello, Mr Taiwo Abiona and Mr Nathaniel Afolabi for their assistance on the data management.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML