-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Mathematics and Statistics

p-ISSN: 2162-948X e-ISSN: 2162-8475

2015; 5(3): 95-110

doi:10.5923/j.ajms.20150503.01

Determinants and Cross-Regional Variations of Contraceptive Prevalence Rate in Ethiopia: A Multilevel Modeling Approach

Tesfay Gidey Hailu

Department of Statistics, Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Tesfay Gidey Hailu , Department of Statistics, Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The Ethiopian population grew at an alarming rate hence the increasing growth of population has become an urgent problem in Ethiopia. Contraception use is the main contributor of fertility declining in all levels and groups of people. On the other hand, to reach the MDGs giving attention to the importance and benefits of lowering population growth is mandatory. Family planning workers hence should make an effort to meet the needs of existing contraceptive users, and also to address socio-economic, demographic and other barriers for contraceptive users in the society. Some studies in Ethiopia (very specific to particular areas) have been carried out using standard logistic regression analysis to assess the factors that could influence contraception use. However, these methods did not assume any higher level grouping (region) or clustering effect (households) in the population as a result the estimates obtained from such analysis that ignores population structure will often be biased. Moreover, these studies lacks generalizability to a country level of Ethiopia as being conducted in particular areas. Ethiopia is a home of multi-ethnic and multi-culture people hence current contraception use may vary between women of different clusters, individuals and regions of the country. This research hence used a three-level random effect logistic model to analyze a national survey data by taking hierarchical sources of variability into account that comes from different levels of the data, which is novel in the estimates of determinants of current contraception use. Multiple multilevel modeling found that there was significant variation of current contraceptive use across clusters and to a lesser extent across regions. About 3.11% of the total variation on current contraception use was attributable to region-level factors and 15.05% was attributable to cluster level factors. Moreover, age categories (mostly 20 to 44 years), being wealthier, being educated, urban dwellers, knowledge on family planning, being married and having access to mass medias (radio, television or reading newspapers) showed an increased pattern with respect to current contraception use. The Ethiopian National Family Planning Programme should intensify its information, education and communication programmes on family planning to cover specific population who poorly utilized contraception use and to identify key geographic areas for further investigation. The strengthening of the health programs on advocating the benefits of family planning through mass media, focusing on young women (being they are the most productive people) particularly those with no or little education, targeting on Somali region and nuwer ethnic group while designing services would greatly improve the proportion of contraception use. Moreover, efficient distribution of health care facilities offering family planning services among women of urban and rural residents are required. This multilevel approach hence provides critical evidence on current barriers to contraception use and suggests policies which could improve the proportion of contraception users. The findings of this research therefore might be helpful for health programs to notify national efforts targeting on specific population or sub-groups who mostly under-used the contraception services as well as to identify key geographic areas for further investigation. Similarly, it enhances the ability of individuals to reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancies and acquiring or transmitting of infectious disease such as HIV/AIDS. The findings could also be helpful for policy making, monitoring and evaluating the activities for the government and other concerned agencies.

Keywords: Determinants, Contextual and individual factors, Contraception use, Multilevel modeling, Ethiopia

Cite this paper: Tesfay Gidey Hailu , Determinants and Cross-Regional Variations of Contraceptive Prevalence Rate in Ethiopia: A Multilevel Modeling Approach, American Journal of Mathematics and Statistics, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 95-110. doi: 10.5923/j.ajms.20150503.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The insistently high levels of fertility in Ethiopia, together with declining mortality, have given rise to rapid growth in population. The population size has increased by more than 7 times in over a century, from 11.5 million in 1900 to 83 million in 2010. The country’s TFR increased over three decades, from about six lifetime births per woman to 7.7 in the 1990s, after which it gradually declined to 4.8 by 2011 [1]. Unwanted pregnancy and unmet need for family planning are still high in Ethiopia. As a result, women are characterized by high fertility of 4.8 children per woman and this would make Ethiopia the second most populous country in Africa next to Nigeria with a population of nearly 83 million in 2010 [1, 2]. The population grows at a rate of 2.6 percent per annum. The vast majority of the people (84 percent) reside in rural areas, agriculture being the major source of livelihood [3]. In Ethiopia, women of reproductive age make up one-fifth of the total population and about 45% of the female population.The women in Ethiopia play the principal roles in the rearing of children and the management of family affairs as in most African countries. On the other hand, the health status of these women remains poor. The maternal mortality ratio in Ethiopia is estimated at 676 per 100,000 live births, which is one of the highest in the world [3]. Therefore, promotion of family planning in countries with high birth rates has the potential to reduce poverty and hunger and avert 32% of all maternal deaths and nearly 10% of childhood deaths [4]. It would also contribute substantially to women’s empowerment, achievement of universal primary schooling, and long-term environmental sustainability. In the past few decades, family-planning programs have played a major part in raising the prevalence of contraceptive practice from less than 10% to 60% and reducing fertility in developing countries from six to about three births per woman [4]. Contraceptive use hence can improve maternal health and is one of the strategies of family planning to achieve improved maternal health worldwide [5]. Contraceptive use, in much of sub-Saharan African countries, is seen as vigorous to protecting women’s health and rights, impacting upon fertility and population growth, and promoting economic development. Worldwide, contraceptives help prevent an estimated 2.7 million infant deaths and the loss of 60 million years of healthy life [6]. Yet, today more than 200 million women and girls in developing countries who do not want to get pregnant lack access to contraceptives, information, and services in which, for many, will cost them their lives [7].It has been noted that contraception use is the main contributor of fertility declining [8, 9]. It is known that rapid population growth have different adverse consequences such as a high unemployment rate, poor economic performance, a high demand for social services, and a decrease in resources. The government of Ethiopia hence adopted an explicit population policy in 1993 with an overall objective of harmonizing the country’s population growth rate with that of the economy [10]. The policy mainly aims to achieve a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 4 children per women by 2015. One of the major strategies of the policy has been to expand family planning program so that contraceptive prevalence increases to 44% by 2015 [10]. To this end the Policy aims to expand the diversity and coverage of family planning service delivery through clinical and community based outreach services; encouraging and supporting the participation of non-governmental organizations in the delivery of population and family planning related services; creating conditions that will permit users the widest possible choice of contraceptives by diversifying the method mix available in the country.Current use of contraceptive methods is one of the indicators most frequently used to assess the success of family planning programmes. A descriptive analysis made by the 2011 EDHS has reported that the rates of contraception use are varying by different demographic factors, socio economic variations and therefore presents current use of contraceptive methods among all women, currently married women, and sexually active unmarried women, by age group, region, place of residence, wealth index, education status and other variables. The contraceptive prevalence rate for all Ethiopian women age 15-49 is 20 percent (EDHS 2011). The contraceptive prevalence rate is 29 percent for currently married women, and 57 percent for sexually active unmarried women [11]. These variations of contraception use observed among regions, place of residence, marital status, wealth index and other factors demands for continued efforts to improve understanding of determinants associated with contraception use in Ethiopiato identify target groups for specific interventions using some advanced statistical method.This study used data from the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) and the sample was selected using a stratified, two-stage cluster design and the enumeration areas (EAs) were the sampling units for the first stage. The structure of data in the population collected during the national survey is hierarchical as the surveys are based on multistage stratified cluster sampling. This clustering effect often introduces multilevel correlation among the observations that can have implications for the model parameter estimates [12, 13]. For instance, Ethiopiais a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural country and the society may have different view on accepting contraceptive methods. This situation indicates that the assumption of conditional independence of responses of individuals on probability of contraception use who are living in the same area (cluster) given the covariates may not be longer valid. This indicates that current contraception use may be affected by unobserved regional and clustering effects at different level of the factors. Unwanted pregnancy and unmet need for family planning are still high in Ethiopia. It has been noted that contraception use is the main contributor of fertility declining in all levels and groups of people. On the other hand, to reach the MDGs giving attention to the importance and benefits of lowering population growth is mandatory. Family planning workers hence should make an effort to meet the needs of existing contraceptive users, and also to address socio-economic, demographic and other barriers for contraceptive users in the society. Hence, identifying determinants associated with current contraception use among different individuals and community groups is important in promoting the service.Some studies have identified several individual and country level variables that could influence the rate of contraception use. Direct comparison, however, between individual studies is often unrealistic as these studies were conducted in different national contexts and may not include similar measures or adjust for the same variables. Some studies in Ethiopia (very specific to particular areas) have also been carried out using standard logistic regression analysis to assess the factors that could influence contraception use. However, these methods do not assume any higher level grouping (region) or clustering effect (households) in the population as a result the estimates obtained from such analysis that ignores population structure will often be biased [12, 13]. Moreover, these studies lacks generalizability to a country level of Ethiopia as being conducted in particular areas. Ethiopia is a home of multi-ethnic and multi-culture people hence current contraception use may vary between women of different clusters, individuals and regions of the country. Yet, very few studies in Ethiopia have been conducted to identify determinants associated with current contraception use among women aged 15-49 years old at a country level considering the random effects that could rise as result of both individual and contextual factors simultaneously. This study therefore used to analyze such large scale survey data by taking hierarchical sources of variability into account that comes from different levels of the data mainly clusters, regions and individuals simultaneously.The appropriate statistical method therefore to analyse current contraception use using data from this large scale survey is based on nested sources of variability. In this regard, the units at lower level are individuals (Individuals: level-1) who have been asked to currently contraception use women aged 15-49 years old and who are nested within units at higher level (clusters: level-2) and the clusters are again nested within units at the next higher level (regions: level-3). This may indicate that, due to hierarchical structure of the data, the probabilities of current contraception use are not independent for those of women who came from same community. This is because women from the same cluster may share common exposure to practice the contraception. Furthermore, the proportion for contraception use would improve if the majority of the population continues to learn about contraception use importance in all levels (cluster and region) of people in Ethiopia. This study therefore aims to understand determinants (both individual and contextual levels simultaneously) affecting the current contraception use among women in Ethiopia. The outcome variable in this study is “current contraception use” which is a binary and hence multilevel logistic regression model is logical for modeling.This study hence used a three-level random intercept logistic model to estimate the effect of unobserved characteristics of cluster and region of the respondents on the likelihood of contraception use, which is novel in the estimates of determinants of current contraception use. This multilevel approach hence provides critical evidence on current barriers to contraception use and suggests policies which could improve the proportion of contraception users. The findings of this research therefore might be helpful for health programs to notify national efforts targeting on specific population or sub-groups who mostly under-utilized the contraception services as well as to identify key geographic areas for further investigation. As a result, the population might be benefited if the contraception service is increased. Similarly, the benefits of contraception use can be seen at the individual, community and population levels. It enhances the ability of individuals to reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancies and acquiring or transmitting of infectious disease such as HIV/AIDS. The findings could also be helpful for policy making, monitoring and evaluating the activities for the government and other concerned agencies. It also helps individuals to have enough knowledge about use and practice of contraceptive methods among women in Ethiopia. In summary, the research questions that this study addressed are the following: What are the individual and contextual determinants that affect current contraception use? Which determinants (individual or community level) are influential for contraception use?

2. Methods

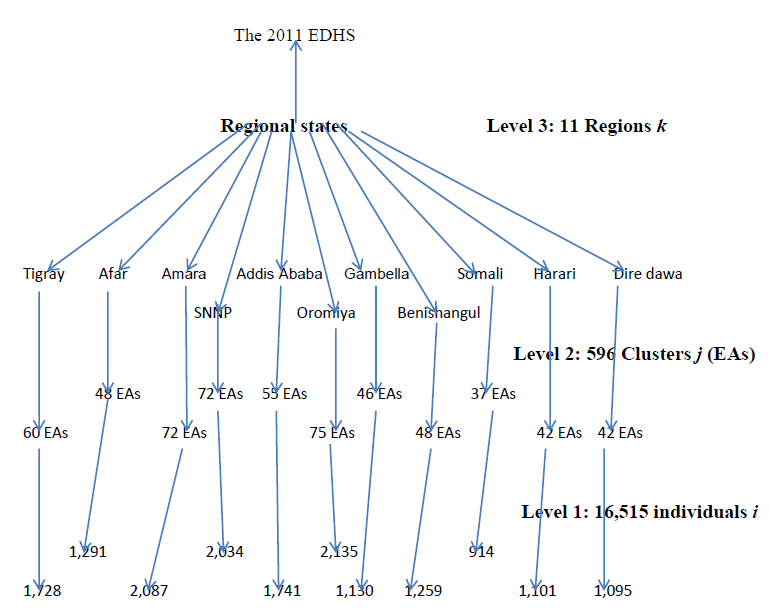

- This study used data from 2011 Ethiopian DHS women’s questionnaire; the most recent national dataset on current contraception use that is available as of January 2012. The analysis is specific to a nationally representative sample of women (aged 15 – 49 years) from all eleven administrative regions in the country. Details relevant to the complex sampling design are available in the EDHS Final Report (EDHS 2011).The structure of data in the population collected during the national survey is hierarchical and a sample from such a population can be viewed as a multistage sample (Figure 1). The appropriate methodology hence used to analyze such large scale survey data has to take into account the hierarchical sources of variability which come from different levels of the data. If we ignore the fact that, in general, clustering occurs in a population, the results will be misleading. For survey and longitudinal data, random effects are useful for modeling intra-cluster correlation; that is, observations in the same cluster are correlated because they share common cluster-level random effects. Hence, multilevel logistic modeling techniques allow us to assess the variations that could possibly occurat several levels of the outcome variable called ‘current contraception use’. For example, we can assess the probability of current contraception use that an individual ith who is nested in jth cluster of kth region simultaneously at a time.

| Figure 1. The three-level Hierarchical structure of the 2011 EDHS data among women, Ethiopia, 2014 |

2.1. The Multilevel Logistic Regression Analysis

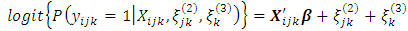

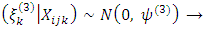

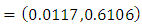

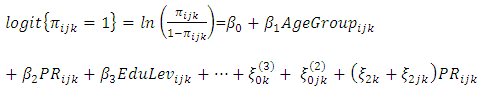

- In multilevel modeling research, the clustering effect of the sample’s data should be taken into consideration during data analysis. This clustering sampling system often introduces multilevel correlation among the observations that can have implications for the model parameter estimates. For multistage clustered samples, the dependence among observations often comes from several levels of the hierarchy. This indicates that contraception use may be affected by unobserved regional and clustering effects at different level of the factors. For instance, in a federal and democratic republic system such as Ethiopia’s, with high level of decentralization, one might think of variations in health policies and priorities at the regional state level. Hence, the health services, for example health equity, quality service and proximity /distance to health institutions may affect contraception use. Furthermore, social and behavioral factors such as religion and local cultures shared with in the community will have an impact on contraception use. Under such situations, the assumption of conditional independence of responses of individuals living in the same area (cluster) given the covariates may be violated. Therefore, the appropriate statistical method to analyse the current contraception use data from this survey is based on nested sources of variability. In this regard, the units at lower level are individuals (Individuals: level-1) who have been asked to current contraception use i.e. women 15-49 years old and who are nested within units at higher level (clusters: level-2) and the clusters are again nested within units at the next higher level (regions: level-3). This may indicate that, due to hierarchical structure of the data, the probabilities of contraception use are not independent for those of women who came from same community. This is because women from the same cluster may share common exposure to contraception use. The outcome variable in this study is “current contraception use” which is a binary and hence multilevel logistic regression model is logical for modeling. The functional form of the three-level random intercept logistic regression can be expressed as described in Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal (2008) (13):

| (1) |

is the probability of contraception use for an individual ith, in the jth cluster in the kth region of Ethiopia;

is the probability of contraception use for an individual ith, in the jth cluster in the kth region of Ethiopia;  is

is  row vector of characteristics which may be defined at the individual ith, who is living in cluster jth located at kth region of the country;

row vector of characteristics which may be defined at the individual ith, who is living in cluster jth located at kth region of the country;  is a

is a  column vector of regression parameter estimates; and the quantities

column vector of regression parameter estimates; and the quantities  and

and  are the random intercept terms for level 2 (the cluster) and level 3 (region) respectively. In this case, the random-intercept terms denoted that the combined effect of all unobserved heterogeneity which are excluded at cluster-level and regional-level that may affects current contraception use behaviour of individuals in some clusters and regions. Therefore, the random-intercepts represent unobserved heterogeneity in the overall response.These are assumed to have normal distribution with mean zero and variances

are the random intercept terms for level 2 (the cluster) and level 3 (region) respectively. In this case, the random-intercept terms denoted that the combined effect of all unobserved heterogeneity which are excluded at cluster-level and regional-level that may affects current contraception use behaviour of individuals in some clusters and regions. Therefore, the random-intercepts represent unobserved heterogeneity in the overall response.These are assumed to have normal distribution with mean zero and variances  and

and  (13, 14). That is,v

(13, 14). That is,v  the variance component at regionslevel given any covariate is independent across the regions.v

the variance component at regionslevel given any covariate is independent across the regions.v  the variance component at cluster level given any covariate is independent across the clusters and regions. It is clear that the variance component at regions

the variance component at cluster level given any covariate is independent across the clusters and regions. It is clear that the variance component at regions  is the residual between regions. Similarly, the variance component at clusters

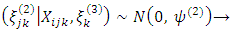

is the residual between regions. Similarly, the variance component at clusters  is the residual between clusters nested with in regions.The variance components estimate for both region and cluster levels have been used to calculate intra-unit correlation coefficients in order to examine the extent to which how contraception use behaviour of individuals was associated for those who live in clusters nested in regions of the country, before and after taking into account the effect of significant covariates. Since individuals within the same clusters are also within the same region, the intra-cluster correlation includes regional variances (15). Thus, the intra-cluster

is the residual between clusters nested with in regions.The variance components estimate for both region and cluster levels have been used to calculate intra-unit correlation coefficients in order to examine the extent to which how contraception use behaviour of individuals was associated for those who live in clusters nested in regions of the country, before and after taking into account the effect of significant covariates. Since individuals within the same clusters are also within the same region, the intra-cluster correlation includes regional variances (15). Thus, the intra-cluster  and intra-region

and intra-region  correlation coefficients are, respectively, given by

correlation coefficients are, respectively, given by | (2) |

denotes that the total variance at region level;

denotes that the total variance at region level;  is the total variance at cluster level; and

is the total variance at cluster level; and  is the total variance at individual level. In multilevel logistic regression model, the residuals at individuals level (level 1) are represented by

is the total variance at individual level. In multilevel logistic regression model, the residuals at individuals level (level 1) are represented by  and assumed to have a standard logistic distribution with mean zero and variance

and assumed to have a standard logistic distribution with mean zero and variance  , where π is the constant 3.1416 (16).

, where π is the constant 3.1416 (16).2.2. Ethical Considerations

- This study used data from 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey to examine determinants for current contraception use among women aged 15-49 years in Ethiopia (The data can be obtained through the researcher’s email address: tesfaygidey21@gmail.com). The data were collected over 6-months (November 2010 – April 2011) by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) under the auspices of the Ministry of Health. The researcher has been authorized by MEASURE DHS authority to work on 2011 EDHS of contraception dataset. I the investigator have treated the EDHS 2011 as confidential and no effort was made to identify any household or individual respondent interviewed in the survey. Respondents’records/information was anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis. The dataset obtained from 2011EDHS has not been passed on to other researchers without the written consent of DHS/EDHS. The principal investigator or user of the data is also intended to submit a copy of any reports/publications resulting from using the 2011 EDHS datasets. This report should also be sent to the attention of the EDHS data archive. Moreover, the study is meant for research purpose and it was not attempted to harm anybody in any way.

3. Results and Analysis

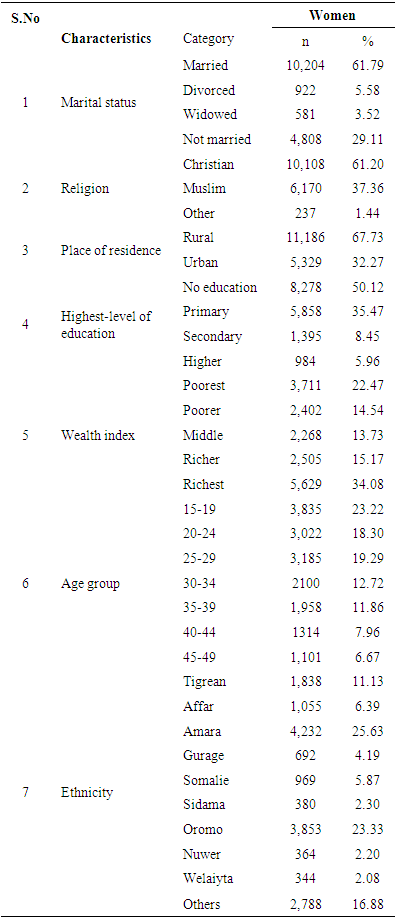

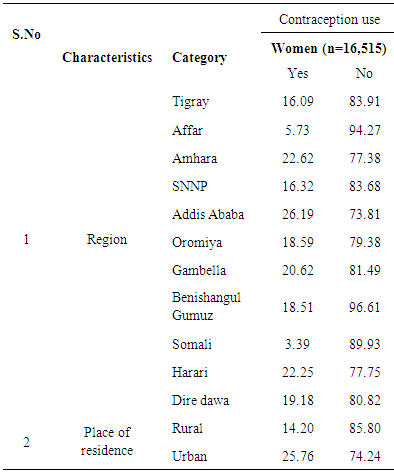

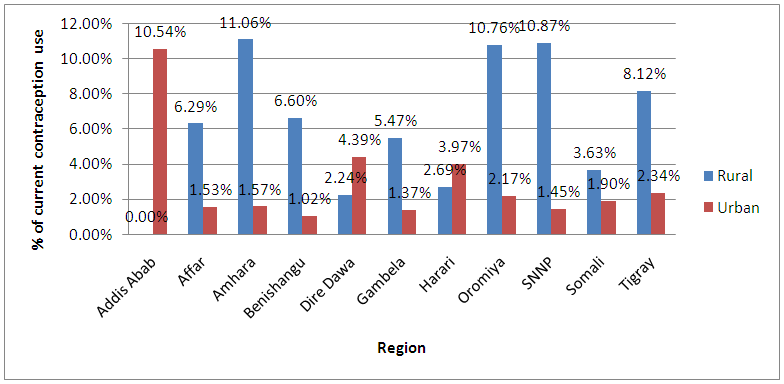

- Current use of contraceptive methods is one of the indicators most frequently used to assess the success of family planning programmes. This section therefore presents current use of contraceptive methods among all women, currently married women, and sexually active unmarried women, by age group, place of residence, wealth index, education status and other variables. The contraceptive prevalence rate for all Ethiopian women age 15-49 is 20 percent (EDHS 2011). The contraceptive prevalence rate is 29 percent for currently married women, and 57 percent for sexually active unmarried women. The current use of contraceptive dataset of Ethiopian DHS 2011 contained 16,515 women participants whose ages range from 15 to 49 years. More than two-thirds of women participants 10,204 (61.79%) were married. Of women participants 10,108 (61.20%) were Chirstians. In regard to their ethnicity composition, majority of the women participants were Amara, Oromo and Tigreans which accounts for 4,232 (25.63%), 3,853 (23.33%) and 1,838 (11.13%) respectively. More than two-thirds of the women participants were from ruralareas. In addition, majority of women participants 8,278 (50.12%) were not educated. Moreover, of women participants, 3,711 (22.47%) and 5,629 (34.08%) were poorest and richest respectively (Table 1).

|

|

| Figure 2. Distribution of current contraception use by region and place of residence among women, Ethiopia, 2014 |

3.1. The Multilevel Logistic Regression for Binary Outcome Analysis

- This study used STATA version 11.1 of statistical package to analyze current contraception use dataset of multilevel data in its nature which is obtained from 2011 EDHS. To reflect the data’s hierarchical structure in the analysis it is therefore useful to consolidate the data. The current contraception use data were first sorted in such a way that all records for the same highest level (level-3: Regions) unit are grouped together and within this group, all records for a particular higher level (level-2: Clusters) unit are adjacent and within this group, all records for the lowest level (level- 1: Individuals) unit are also adjacent.Univariate multilevel logistic model was first fitted on contraception use dataset for women in order to select covariates which then will be used as input/covariates at the time of multilevel analysis. All the variables used in this study were found to be significant in the univariate multilevel logistic analysis which was done before fitting the final multilevel analysis. The cut point for the level of significance used in univariate multilevel analysis was fixed to be less than 25% (P-value<0.25). This was done because of not to remove important predictors at an early stage (before fitting the final model) of the analysis. However, the level of significance was fixed to be less than 5% (P-value<0.05) for drawing any kind of conclusion about the predictors in which the model is different from univariate multilevel model. The multilevel modeling process therefore was built step by step. The first step examined the null model (empty model with no predictor) was first fitted to measure the overall probability of an individual women was being used for contraception without an adjustment for predictors. The second step included first the univariate multilevel logistic analysis and then random slope multilevel univariate analysis for each of the selected explanatory variables. The third step considered a model building for three levels multiple multilevel logistic regression analysis. The Wald χ2 test was used to determine the significance of each model as a whole as well as to determine significance of individual β coefficients.

3.2. The Random Intercept Only Model

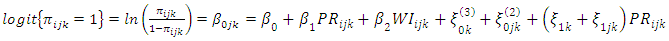

- Firstly, an empty multilevel model with no predictors was fitted to current contraception use data set and this means that a random intercept-only model could predicts the probability of an individual current contraception use. The functional form of the model is given by:

| (3) |

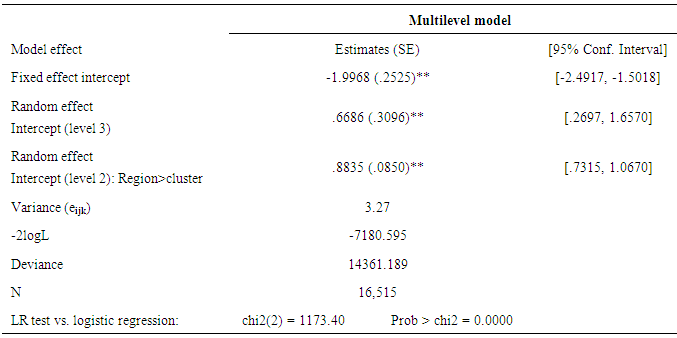

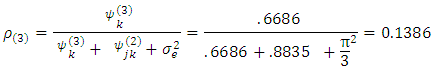

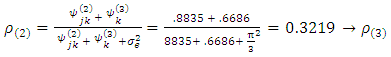

indicated that the average of all regions or all clusters for experiencing the outcome of interest that is being used contraception. Moreover, the estimates for the random effects of the three-level intercept-only model explained that the unique effect up on the use of contraception behaviour of an individual that came from each region (level 3) and cluster (level 2). The percentage of observed variation in the dependent variable (current use of contraception) attributable to regional level is found by dividing the variance for the random effect of the region by the total variance. This means that the intra-correlation coefficient (ICC) for women will be given as follows:

indicated that the average of all regions or all clusters for experiencing the outcome of interest that is being used contraception. Moreover, the estimates for the random effects of the three-level intercept-only model explained that the unique effect up on the use of contraception behaviour of an individual that came from each region (level 3) and cluster (level 2). The percentage of observed variation in the dependent variable (current use of contraception) attributable to regional level is found by dividing the variance for the random effect of the region by the total variance. This means that the intra-correlation coefficient (ICC) for women will be given as follows: and

and

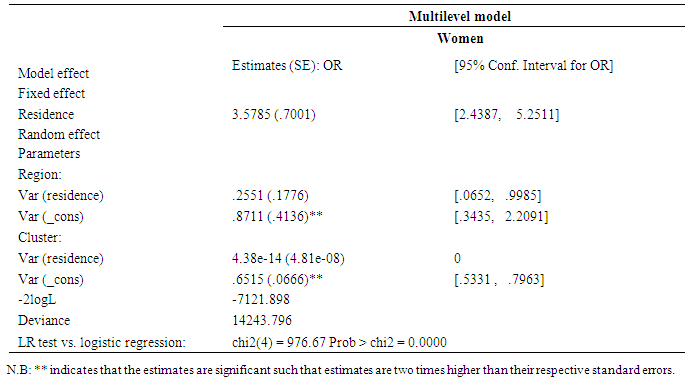

of current contraception use among women at regional and cluster levlel (Table 3). The intra correlations coefficient at the regional and cluster level for women were found to be 0.1386 and 0.3219 respectively. These measures indicate that the correlation of current contraception use between two individuals in the same region and between two measurements on the same individual (in the same region). One can also conclude that 13.86% of the variation in contraception use of women is attributed to the regions and 32.19% to the cluster (which includes the region). Therefore, the addition of the regional and cluster specific effects were found to be significant on modeling the contraception use for women. The random intercept model only(with random effects of region and cluster) is therefore better than the fixed intercept only model on modeling the heterogeneity of contraception use that could arise from different levels of the data simultaneously. The random effects model also, that is, the region and cluster specific effects are assumed to be distributed normally for the purpose of estimation.

of current contraception use among women at regional and cluster levlel (Table 3). The intra correlations coefficient at the regional and cluster level for women were found to be 0.1386 and 0.3219 respectively. These measures indicate that the correlation of current contraception use between two individuals in the same region and between two measurements on the same individual (in the same region). One can also conclude that 13.86% of the variation in contraception use of women is attributed to the regions and 32.19% to the cluster (which includes the region). Therefore, the addition of the regional and cluster specific effects were found to be significant on modeling the contraception use for women. The random intercept model only(with random effects of region and cluster) is therefore better than the fixed intercept only model on modeling the heterogeneity of contraception use that could arise from different levels of the data simultaneously. The random effects model also, that is, the region and cluster specific effects are assumed to be distributed normally for the purpose of estimation.

|

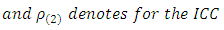

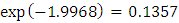

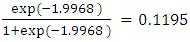

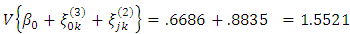

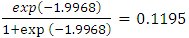

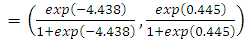

as seen in (Table 3). This corresponds to a predicted probability of

as seen in (Table 3). This corresponds to a predicted probability of  . Suppose that the region’s log-odds of current contraception use,

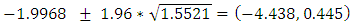

. Suppose that the region’s log-odds of current contraception use,  , is approximately normally distributed with mean -1.9968 and variance,

, is approximately normally distributed with mean -1.9968 and variance,  . Hence, the 95% confidence interval for

. Hence, the 95% confidence interval for  is

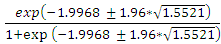

is  . Similarly, these log-odds can be converted to predicted probabilities such that

. Similarly, these log-odds can be converted to predicted probabilities such that  and the corresponding 95% CI for the predicted probability is given by

and the corresponding 95% CI for the predicted probability is given by

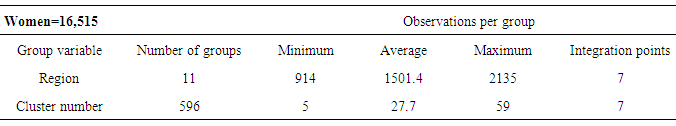

. This indicates that the multilevel effects (that is the random effects at different levels) would impact the rate/prevalence of current contraception use to vary from 1.17 percent to 61.06 percent within the regions (clusters nested with in regions) and no predictor has been included in this model. Moreover, the likelihood ratio test indicated that the random effect model is highly significant in explaining the variation of current contraception use observed among women (P-value=0.0000<0.05). Hence, the random intercept model is better in comparison to standard logistic regression on explaining the variation of contraception use observed among women.The output in Table 4 below shows that there are 11 regions with an average of 1501 participants for a total of 596 clusters, with between 5 and 59 observations each for a total of 16,515 women.

. This indicates that the multilevel effects (that is the random effects at different levels) would impact the rate/prevalence of current contraception use to vary from 1.17 percent to 61.06 percent within the regions (clusters nested with in regions) and no predictor has been included in this model. Moreover, the likelihood ratio test indicated that the random effect model is highly significant in explaining the variation of current contraception use observed among women (P-value=0.0000<0.05). Hence, the random intercept model is better in comparison to standard logistic regression on explaining the variation of contraception use observed among women.The output in Table 4 below shows that there are 11 regions with an average of 1501 participants for a total of 596 clusters, with between 5 and 59 observations each for a total of 16,515 women.

|

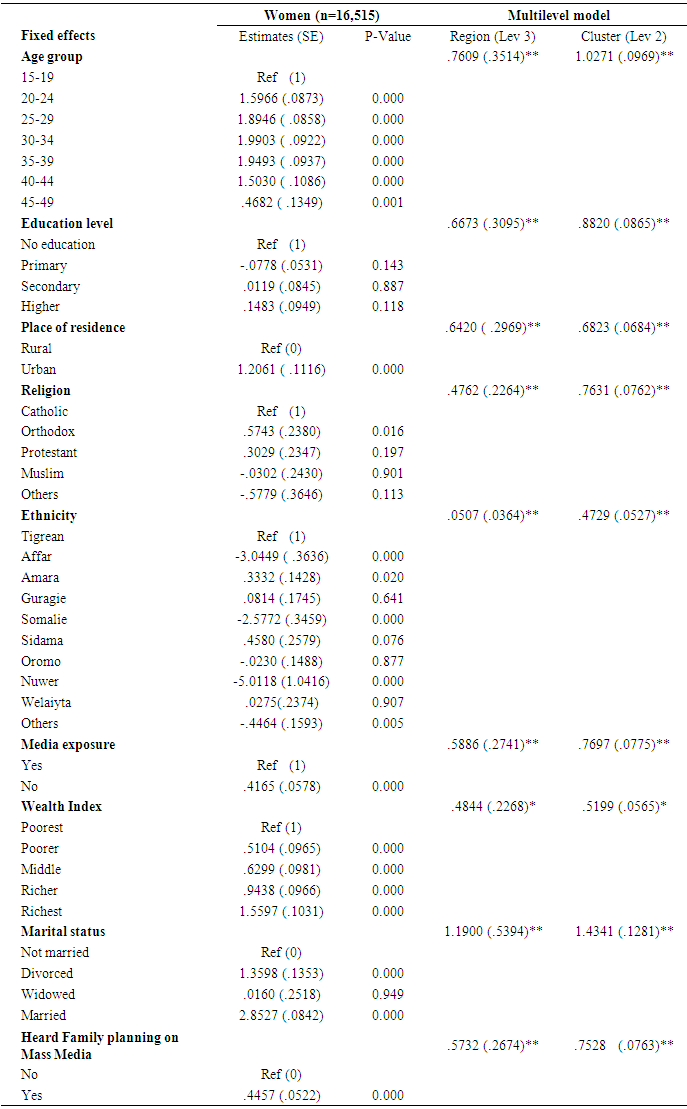

3.3. Multilevel Univariate Logistic Model

- A multilevel univariate logistic analysis for women is presented in Table 5 and each of the multilevel models presents a random intercept (specific effects due to region and cluster) and a fixed slope for the particular variable fitted with the binary outcome of current contraception use. The parameter estimates (β’s) obtained from multilevel logistic regression can be presented as odds ratios and predicted probabilities. The multilevel analysis models the log odds of the outcome; however, this study prefers to interpret the model in terms of odds ratios rather than predicted probabilities. In standard logistic regression, it is clear that the odds ratio can also be calculated from the log odds. Similarly, odds ratios can be calculated in the multilevel model as done in standard logistic regression. The parameter estimates related to a particular variable that are calculated from a multilevel logistic regression therefore can be interpreted as the individual estimates associated with a predictor as may increase or decrease the log-odds of the outcome (contraception use). Secondly, the log odds can be converted to predicted probabilities and odds ratios.

- The multilevel univariate analysis indicates that the contraception prevalence rate was significantly associated with the age group of the respondents and these random effects at region and cluster levels were found to be significant. Exceptionally, there was no association between education category of secondary and current contraception use (P-value=0.887> 0.25). It means that there was no significant difference in contraception use among women whose education status are secondary and no education at all. But, overall education was asignificant predictor and kept for next multilevel model. Moreover, ethnicity was found significantly associated with current contraception use among Affar, Somalie and Nuwer women compared to the reference category that of Tigrean women. In contrast to this, there was no significant difference in contraception use between the Amara, Guragie, Sidama, Welaiyta and Oromo women compared to the Tigrean women. But, overall ethnicity was a significant predictor and kept for next multilevel model. Similar scenario was observed for religion. Furthermore, place of residence, marital status, media exposure, wealth index and heard family planning on mass media were reported as significant predictors for explaining the observed variation on current contraception use of women at a stage of multilevel univariate analysis. It is also important to note that the random effects at region and cluster levels were found to be significant at all univariate analysis in which the outcome variable fitted with a predictor.

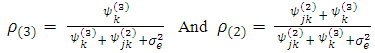

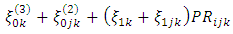

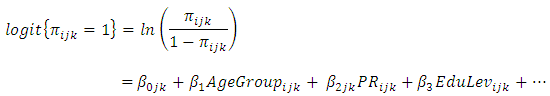

3.4. Multilevel Univariate Model for Random Slope

- Random effects/slope univariate model allows the effect that the coefficient of the predictor variable to vary from region to region and from cluster to cluster. The random effects model (with both random intercept and slope) was fitted for two predictors which are wealth index and place of residence. Place of residence was found to be insignificant random effect across both regions and clusters among women. This means that the estimates of the variance components of place of residence allowed varying within region and cluster levels was not greater than 2 times of their standard errors (Table 6). This indicates that the random effect model (i.e. a model with both random intercept and slope if it was significant) allows the variation of current contraception use between rural and urban areas within a region to vary across regions. The three-level random model for place of residence can be written as below:

| (4) |

|

is in fact the residual

is in fact the residual  of the model which is a function of place of residence. But, the random slope for place of residence was in significant at both region and cluster level. Hence, the random slope model for place of residence was being allowed to vary at region or cluster level was not considered any more while fitting the final multiple multilevel model with all significant predictors (Table 6). Moreover, the random slope model for wealth index didn’t converge even after several iterations and hence not fitted in the final multilevel model.

of the model which is a function of place of residence. But, the random slope for place of residence was in significant at both region and cluster level. Hence, the random slope model for place of residence was being allowed to vary at region or cluster level was not considered any more while fitting the final multiple multilevel model with all significant predictors (Table 6). Moreover, the random slope model for wealth index didn’t converge even after several iterations and hence not fitted in the final multilevel model.3.5. Multilevel Multiple Logistic Model

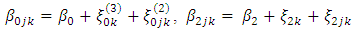

- The multiple logistic of multilevel model is fitted with all the significant predictors, found atmultilevel univariate analysis to assess their simultaneous effect on current contraception use. The proposed functional form of the multilevel model is:

| (5) |

| (6) |

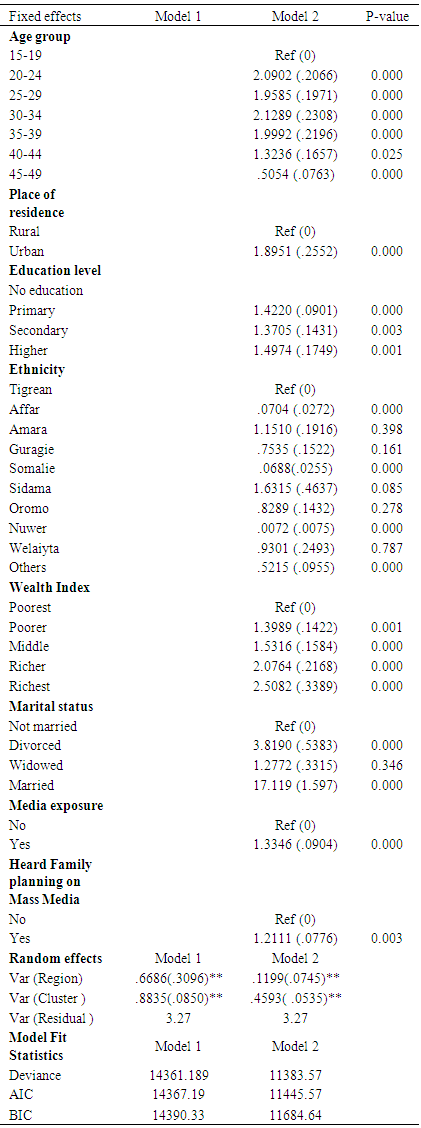

The multiple multilevel modelling showed that, age group, education, wealth index, marital status, heard family planning on mass media and media exposure have been found significantly associated with women’s current contraception use. Moreover, ethnicity was found significantly associated with current contraception use among Affar, Somalie and Nuwer women compared to the reference category that of Tigrean women. In contrast to this, there was no significant difference in contraception use between the Amara, Guragie, Sidama, Welaiyta and Oromo women compared to the Tigrean women. Religion was also found to be insignificant on explaining the variation of current contraception use observed among women. The variation of contraception use among women was significant (p <0.05) at all levels of the hierarchy (individual, cluster and region). It has been also found that the random effects at cluster and region levels were significant on explaining the variations of contraception use among women. In summary, the random effects multiple multilevel model results indicated that all the predictors are not equally and effectively defining the characteristics of women of all the clusters and all the regions on experiencing the probability of contraception use. This showed that those of women belonging to different wealth categories and place of residences of same cluster might differ on contraception use significantly across the region. One can conclude that, current contraception use is therefore correlated among women in the same cluster within each region but the correlation differs from region to region. However, fitting a multiple multilevel model with both random intercept and slope is really consuming time as the hierarchical structure of the data is more complex. Although the more complex model explains the variations of contraception use among women better than the other model but here in this study the variance components for place of residence was found to insignificant (Table 7). And, the random slope model for wealth index didn’t converge even after several iterations. Hence, the three level random intercept multilevel model is considered.N.B: Model 1: Represents random intercept model i.e. an empty modelModel 2: The final multiple multilevel logistic model with significant predictors associated with the probability of current contraception use among women aged 15-49 years old in Ethiopia

The multiple multilevel modelling showed that, age group, education, wealth index, marital status, heard family planning on mass media and media exposure have been found significantly associated with women’s current contraception use. Moreover, ethnicity was found significantly associated with current contraception use among Affar, Somalie and Nuwer women compared to the reference category that of Tigrean women. In contrast to this, there was no significant difference in contraception use between the Amara, Guragie, Sidama, Welaiyta and Oromo women compared to the Tigrean women. Religion was also found to be insignificant on explaining the variation of current contraception use observed among women. The variation of contraception use among women was significant (p <0.05) at all levels of the hierarchy (individual, cluster and region). It has been also found that the random effects at cluster and region levels were significant on explaining the variations of contraception use among women. In summary, the random effects multiple multilevel model results indicated that all the predictors are not equally and effectively defining the characteristics of women of all the clusters and all the regions on experiencing the probability of contraception use. This showed that those of women belonging to different wealth categories and place of residences of same cluster might differ on contraception use significantly across the region. One can conclude that, current contraception use is therefore correlated among women in the same cluster within each region but the correlation differs from region to region. However, fitting a multiple multilevel model with both random intercept and slope is really consuming time as the hierarchical structure of the data is more complex. Although the more complex model explains the variations of contraception use among women better than the other model but here in this study the variance components for place of residence was found to insignificant (Table 7). And, the random slope model for wealth index didn’t converge even after several iterations. Hence, the three level random intercept multilevel model is considered.N.B: Model 1: Represents random intercept model i.e. an empty modelModel 2: The final multiple multilevel logistic model with significant predictors associated with the probability of current contraception use among women aged 15-49 years old in Ethiopia4. Discussion

- This study used multilevel logistic regression analysis to the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data source of current contraception use dataset to examine the determinants and cross-regional variations of contraception use among women aged 15 to 49 years in Ethiopia. The models include both individual and contextual levels (i.e. region and cluster) of factors simultaneously. The main objective of this study was to provide an overall picture of the general patterns and determinants of current contraception use across regions in Ethiopia. This study therefore will help to notify national efforts targeting on specific population or sub-groups who mostly under-utilized contraception use as well as to identify key geographic areas for further investigation. In summary, this study showed that the probability of current contraception use was relatively higher among wealthier households, higher educated people, those of age categories of 20 to 39 years old, urban residents, married women, who have exposure to mass media and who have heard about family planning in Ethiopia.Generally, contraceptive use is often influenced by characteristics such as education, place of residence and wealth where the poor are the most disadvantaged and less likely to use contraceptives [18]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Ethiopia revealed that educated women and those in the highest wealth quintile are most likely to use contraception [19].This study revealed that (Table 7: model 2) women who were in the age categories of 20 to 39 years old were almost two times more likely to current contraception use than those who were belonging to a reference agecategory (15-19 years). That is, women who were belonging to age categories of 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34 and 35 to 39 years old were (OR=2.09), (OR=1.95), (OR=2.12) and (OR=1.99) more likely to current contraception use compared to these who were belonging to a reference age category respectively while other predictors are holding constant. This showed that those of women belonging to different age categories of same cluster nested with in a region might differ on contraception use significantly across the region. This may justify that the odds of women (of same cluster nested with in a region) who were in the age categories of 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34 and 35 to 39 were more likely to use contraception than those of women who were belonging to the age category of 15 to 19 years old due to the perceived higher risk of unwanted pregnancy and unmet need family planning they face. Moreover, the association between women’s age of 20–39 years old with current contraceptive use was significant and similar to other studies conducted elsewhere [20-22]. In Ethiopia, a woman aged 25–34 years has, at an average, 2–5 children [19] and from this result if a woman has a child then she is likely to use modern contraceptives. This observed association might be explained by the fact that those of women who were belonging to age group of 20 to 39 years old is usually the age of a woman is more likely to get married and have a child or more in a country such as Ethiopia where the median ages at first marriage and delivery are 16.1 and 19.0 years respectively [19]. Moreover, the fact that majority (97%) of the women had ever heard about contraceptives in this group of the population is of paramount importance. This result is in line with the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey report which reported that knowledge of contraception was nearly universal in Ethiopia [23]. However, it is higher among married urban dwellers [23] due to wide scale increase of information and access to contraceptives in Ethiopia [19, 20, 24, 25]. Contraceptive use is lowest among young women, reaches a peak among women in their thirties and declines among older women [26]. This may indicate a high desire for child bearing among young women and a high growing interest of spacing births among women in their thirties. Percentage of contraceptive users declines at older ages of reproduction due to the fact that older women are not at a high risk of pregnancy. Furthermore, this study indicates that current contraceptives use increases with age of the woman reaching a maximum in age 40-44 and declines slightly in age group 45-49 years. The low contraceptive prevalence observed among women aged 15-19 years may be due to the fact that most of these are newly married, and marriage is looked upon as an institution of producing children. Young women (15-19 years) are more likely to be less educated compared to women aged 20-39 years and this could create problems with accessing family planning services. On the other hand, those of women who were belonging to age categories of 45-49 years old were (OR=0.505) 50.5% less likely to current contraception use compared to these who were belonging to a reference age category respectively while other predictors are holding constant. The reduced contraceptive use among older women may be related to the fact that they have reduced their sexual intercourse frequency and most of them may perceived lower risk of unwanted pregnancy and unmet need family planning they could face. Of course, a good number of older women might be not sexually active.

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study used multilevel modeling analysis on current contraception use dataset and the results showed that there was significant variation of current contraception use across clusters and to a lesser extent across regions among women aged 15 to 49 years oldin Ethiopia. About 3.11% of the total variation on current contraception use was attributable to region-level factors and 15.05% was attributable to cluster level factors among women. This indicates that random effects are useful for modeling intra-cluster correlation; that is, observations in the same cluster were correlated because they share common cluster-level random effects and similarly individuals who were nested with in a region were more correlated since they share common region-level random effects. Moreover, the variations on current contraception use that has been observed across clusters and regions were partly explained by individual and contextual background of socio-economic characteristics such as education, wealth index, age-group, marital status, mass media and knowledge on family planning.Generally, this study has proven the general patterns on current contraception use across regions in Ethiopia as well as it identified specific areas which are underutilized for current contraception use services for further investigation. The areas identified for further research include region specific as well as community/cluster specific analyses. The patterns incurrent contraception use observed in clusters nested with in a region call for more in-depth region-level analysis to better understand the patterns of determinants in individual regions, especially those that displaytypical patterns when specific sets of factors are taken into account. The general variations or patterns of current contraception use being observed across clusters and regions to some extent in Ethiopia are important for national efforts in order to promote contraception use services among women in Ethiopia. In conclusion, the results obtained from this multilevel modelling approach on current contraception use among women aged 15 to 49 years old revealed that both individual and contextual level of determinants arecrucial in providing relevant information for the effective utilization of contraception services which has clinical, community and societal importance at all levels. In line with, the determinants of contraceptive use in Ethiopia, as presented in this study, have policy and programme implications for Ethiopia and for other African countries with similar social, cultural and economic conditions. Accordingly, the Ethiopian National Family Planning Programme should intensify its information, education and communication programmes on family planning to cover particularly the geographic areas which poorly utilized for current contraception and more importantly, adjust them to suit local conditions. Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are forwarded. l It is advisable to target young women (being they are the most productive people), particularly those with no or little education, with information on reproductive health and to provide them with basic life skills to enable them to avoid early sexual activity and ultimately early marriage.l It is crucial to continue improving girls and young women access to education in the country, as this is important avenue for increasing the women’s use of contraceptives and for empowering women so as to enhance their active participation in market economy. l Mass communication should be thought of and organized to increase knowledge of available options and access, while interpersonal communication should be considered at the community level to induce changes in contraceptive use.l Targeting on Somali region and nuwer ethnic group (Gambella) while designing for family planning services would greatly increase the rate of contraception use.l It is highly important that future ethnographic research should investigate the observation found on nuwer ethnic group in using contraception by comparing with other ethnic groups in Ethiopia.l Efficient distribution of health care facilities offering family planning services among women of urban and rural areas residents are required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- I am very grateful to MEASURE DHS authority that they have offered me all the necessary data and documents which I needed for this work. I would like also to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Wond wosson Terefe Lerebo for his constructive comments, critical readings, encouragements and suggestions which were really important for the accomplishment of this work. Extraordinary thanks go for my almighty God for being with me and granting me grace, guidance and strength throughout my work.

References

| [1] | Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro. 2006. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa and Calverton, MD, USA. |

| [2] | The World Bank group: Available at: http://www. worldbank.org/en/country/ethiopia. Accessed on August 9, 2014. |

| [3] | Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia], Populating and housing census of Ethiopia. 2007. |

| [4] | Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J (2006): Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet 2006, 368(9549):1810-1827. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text. |

| [5] | Starrs A: Preventing the Tragedy of Maternal Deaths: A Report on the International Safe Motherhood Conference: World Bank/World Health Organization/United Nations Fund for Population Activities. Nairobi: World Bank, WHO, UNFPA; February 1987. |

| [6] | Darroch, J.E., Singh, S., & Nadeau, J. (2008). Contraception: an investment in lives, health and development. In: In Brief (No.5). New York: Guttmacher Institute and UNFPA. |

| [7] | London summit on Family Planning. Available at: http:// www.londonfamilyplanningsummit.co.uk/], Accessed on August 9, 2014 |

| [8] | Cleland, J., Phillips, J. F., Amin, S. and Kamal, G. M. (1994). The determinants of reproductive change in Bangladesh: success in a challenging environment (Tech. Rep.). World Bank Regional and Sectoral Studies. |

| [9] | Rani, S. U. and Radheshyam, B. (2007). Inconsistencies in the relationship between contraceptive use and fertility in Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives 33, 31-37. |

| [10] | Transitional Government of Ethiopia [TGE], National population policy of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: TGE 1993. |

| [11] | CSA: Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2011. ICF international Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Authority, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; March 2012. |

| [12] | Mason WM, Wong GM, Entwistle B. 1983. Contextual analysis through multilevel linear model. Socil. Methodol. 13:72-103. |

| [13] | Goldstein H. 3rd edition. Arnold; London: 2003. Multilevel Statistical Models. |

| [14] | Godstein H, Rasbash J. 1996. Improved approximations for multilevel models with binary responses. J.Roy. Statist. Soc. A. 159: 505-13. |

| [15] | Rabe-Hesketh, S. and Skrondal, A. (2008). Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata (2nd Edition). College Station, TX: Stata Press. |

| [16] | Siddiqui O., Hedeker D., Flay B.R., Hu F.B. Intraclass correlation estimates in a school-based smoking prevention study: outcome and mediating variables, by sex and ethnicity. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;144(4):425–433. [PubMed] |

| [17] | Hedeker D., Gibbsons R.D. MIXOR: a computer programme for mixed effects ordinal regression analysis. Computer Methods and Programs in Biometrics. 1996;49:157–176. [PubMed] |

| [18] | Gribble J, Haffey J: Reproductive Health in Sub Saharan Africa; Washington. D.C.: Population Reference Bureau; 2008. PubMed Abstract . . |

| [19] | CSA, ORC Macro. Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey Report: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. CSA, ORC Macro 2005, 2006:54-60. |

| [20] | Kebede Y: Prevalence of contraceptives in Gondar town and the surrounding peasant associations. Ethiop J Health Dev 2000, 14(3):327-334.   |

| [21] | Sorsa S, Kidanemariam T, Erosie L: Health problems of street children and women in Awassa, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2002, 16(2):129-137.   |

| [22] | Arbab AA, Bener A, Abdulmalik M: Prevalence, awareness and determinants of contraceptive use in Qatari women. East Mediterr Health J 2011, 17(1):11-18. PubMed Abstract |

| [23] | King R, Khana K, Nakayiwa S, Katuntu D, Homsy J, Lindkvist P, Johansson E, Bunnell R: Pregnancy comes accidentally - like it did with me’: reproductive decisions among women on ART and their partners in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health 2011, 11(530):1-11. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | PubMed Central Full Text . . |

| [24] | Kebede Y: Contraceptive prevalence in Dembia District, northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2006, 20(1):32-38.  |

| [25] | Arbab AA, Bener A, Abdulmalik M: Prevalence, awareness and determinants of contraceptive use in Qatari women. East Mediterr Health J 2011, 17(1):11-18. PubMed Abstract. |

| [26] | Robey B, Rutstein SO and Morris L. The Reproductive Revolution: New Survey Findings. Population Reports, Series M, Number 11, 1992. |

| [27] | APPIAH, R. (1985) Marriage and use of contraception in Ghana. In: Demographic Patterns in Ghana: Evidence from the Ghana Fertility Survey. Edited by B. Singh, J. Y. Owusu& I. H. Shah.International Statistical Institute, Voorburg, Netherlands. |

| [28] | NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL (1993) Factors Affecting Contraceptive Use in Sub-Saharan Africa. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. |

| [29] | Ainsworth, M., Beegle, K., &Nyamete, A. (1996). The impact of women’s schooling on fertility and contraceptive use: A study of fourteen sub-Saharan African countries. World Bank Economic Review, 10, 85–122. |

| [30] | Rutenburg, N., Ayad, M., Ocho, L.H., & Wilkinson, M. (1991). Knowledge and use of contraception. demographic and health surveys comparative studies No.6, Columbia, MD: Institute for Resource Development. |

| [31] | Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N 2007. Contextual influences on modern contraceptive use in Sub-Saharan Africa. American Journal of Public Health, 97(7): 1233–1240. |

| [32] | Hialemariam A, Berhanu B, Hogan DP 1999. Household organization women’s autonomy and contraceptive behaviour in southern Ethiopia. Studies in Family Planning, 30(34): 302-314. |

| [33] | Tawiah, EO 1997. Factors affecting contraceptive use in Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science, 29: 141-149. |

| [34] | Feyisetan BJ 2000. Spousal communication and contraceptive use among the Yoruba of Nigeria. Population Research and Policy Review, 19(1): 29-45. |

| [35] | Saleem S, Martin B 2005. Women’s autonomy, education and contraception use in Pakistan: A national study. Reproductive Health, 1-8. |

| [36] | J. biosoc. Sci. (1997) 29, 141–149 © 1997 CambridgeUniversity Press: FACTORS AFFECTING CONTRACEPTIVE USE IN GHANA. |

| [37] | Beekle, A.T., & McCabe, C. (2006). Awareness and determinants of family planning practice in Jimma, Ethiopia. International Nursing Review, 53, 269–276. |

| [38] | Mai D, Nami K: Women’s empowerment and choice of contraceptive methods in selected African countries. IntPerspect Sex Reprod H 2012, 38(1):23-33. Publisher Full Text . . |

| [39] | Gillespie D: Contraceptive use and the poor: a matter of choice? PLoS Med 2007, 4(2):241-242. 2007. |

| [40] | Lethbridge DJ: Use of contraceptives by women of upper socioeconomic status. Health Care Women Int 1990, 11(3):305-318. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text. |

| [41] | Bongaarts J, Cleland J, Townsend JW, Bertrand JT, Gupta MD: Family Planning Programs for the 21st Century: Rationale and Design, Volume ix. New York: The Population Council, 2012; 2012:94.  |

| [42] | Tuoane M, Diamond I, Madise N: Use of family planning services in Lesotho: the importance of quality of care and access. AfrPopul Stud 2003, 18:105-132. 2003. |

| [43] | Adebowale AS, Fagbamigbe AF, Bamgboye EA: Contraceptive use: implication for completed fertility, parity progression and maternal nutritional status in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2011, 15(4):60. 2011 PubMed Abstract. |

| [44] | United States Agency for International Development: Urban–rural and Poverty-Related Inequalities in Health Status: Spotlight on Nigeria. 2011.  |

| [45] | Robey B, Rutstein SO and Morris L. The Reproductive Revolution: New Survey Findings. Population Reports, Series M, Number 11, 1992. |

| [46] | Martin E. Palamuleni. North West University, Mafikeng Campus, Private Bag X2046, Mmabatho 2735, Republic of South Africa. |

| [47] | Gage A. Women’s socioeconomic position and contraceptive behaviour in Togo. Studies in Family Planning 1995; 26():264–277. |

| [48] | Cleland J, et. Al. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. The Lancet Sexual and Reproductive Health Series, October 2006. |

| [49] | E. O. TAWIAH (1997): FACTORS AFFECTING CONTRACEPTIVE USE IN GHANA: J. biosoc. Sci. (1997) 29, 141–149 © 1997 Cambridge University Press |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML