-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(9): 3038-3041

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251509.41

Received: Sep. 2, 2025; Accepted: Sep. 22, 2025; Published: Sep. 25, 2025

Treatment of Vulgar Pemphigus Localized on the Oral Mucosa

Rizaev Jasur Alimdjanovich1, Imamov Otabek Sunnatovich2, Toxtayev Gayratillo Shuxratillo ogli3, Safarov Kholikjon Khurshedovich4

1DSc, Professor, Rector, Samarkand State Medical University, Uzbekistan

2DSc, Project Office “Center for Healthcare Projects”, Uzbekistan

3Senior Lecturer, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cosmetology №1, Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan

4Senior Lecturer, Department of Internal Diseases in Family Medicine, Chirchik Branch Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Safarov Kholikjon Khurshedovich, Senior Lecturer, Department of Internal Diseases in Family Medicine, Chirchik Branch Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Pemphigus is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease that often presents with lesions on the oral mucosa and skin. This study aimed to investigate the clinical manifestations, laboratory parameters, and topographic distribution of lesions in patients with different clinical forms of pemphigus. A three-year retrospective analysis was conducted at the Tashkent Dermatovenerological Dispensary, including patients diagnosed with pemphigus based on clinical, cytological, and laboratory findings. Clinical presentations, hematological and biochemical parameters, and urinary abnormalities were systematically assessed, alongside lesion distribution across anatomical zones. The results demonstrated that pemphigus vulgaris was the most prevalent form, particularly among women, and was frequently associated with hematological and biochemical abnormalities, including elevated leukocyte counts, hyperglycemia, and increased C-reactive protein. Topographic analysis revealed involvement of both cutaneous and mucosal sites, with characteristic patterns depending on the clinical subtype. These findings emphasize the importance of early recognition and laboratory confirmation to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes. Further multicenter studies with larger cohorts are warranted to validate these results.

Keywords: Ulcer, Pemphigus, Mucous membrane of the mouth, Topographic zones, Bladder

Cite this paper: Rizaev Jasur Alimdjanovich, Imamov Otabek Sunnatovich, Toxtayev Gayratillo Shuxratillo ogli, Safarov Kholikjon Khurshedovich, Treatment of Vulgar Pemphigus Localized on the Oral Mucosa, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 9, 2025, pp. 3038-3041. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251509.41.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pemphigus encompasses a group of rare, chronic, and potentially life-threatening autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by the formation of intraepithelial blisters on the skin and mucous membranes [25,28]. The pathogenesis is fundamentally driven by autoantibodies directed against desmogleins, which are critical adhesion proteins in desmosomes, leading to the loss of keratinocyte adhesion—a process known as acantholysis. This results in the classic clinical presentation of flaccid blisters and painful erosions.Despite extensive research, the precise aetiology of pemphigus remains incompletely elucidated and is a subject of ongoing debate. It is widely accepted that the disease arises from a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, immunological dysregulation, and environmental triggers. The central pathological mechanism is acantholysis, which develops in response to these various factors [1,14,15,16,19]. Viral infections, particularly those caused by viruses of the herpes family, have been implicated as potential triggers in some cases of pemphigus, suggesting a role for molecular mimicry or non-specific immune activation [2,20,22]. Furthermore, the disease is frequently associated with other autoimmune disorders, such as myasthenia gravis and autoimmune thyroiditis, reinforcing its autoimmune basis and suggesting shared pathogenic pathways or a general state of immune dysregulation [3,8,9,23].The autoimmune nature of pemphigus is strongly supported by the detection of circulating IgG antibodies in patient serum, specifically targeting intercellular components of the epidermis, primarily desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3. The profile of these autoantibodies often correlates with the clinical phenotype; for instance, antibodies against desmoglein 3 are typically associated with mucosal-dominant pemphigus vulgaris, while antibodies against both desmoglein 1 and 3 are linked to mucocutaneous involvement. Crucially, antibody titres have been shown to correlate with disease severity and activity, making them valuable tools for both diagnosis and monitoring treatment response [1,3,4,5,17,24].Among the various forms of pemphigus, pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common subtype and frequently presents with initial lesions on the oral mucosa [26,27]. In fact, for a significant majority of patients (50-70%), the oral cavity is the first and sometimes only site of involvement for a considerable period. These early oral manifestations often appear as painful, persistent erosions and ulcers, rather than intact blisters, as the fragile blisters rupture rapidly in the moist oral environment. This atypical presentation frequently leads to diagnostic challenges and delays, as these lesions are often misdiagnosed as more common conditions such as recurrent aphthous stomatitis, erythema multiforme, or lichen planus by dental practitioners and general physicians [5,11,12,18].This diagnostic delay is a critical concern, as early intervention is paramount for improving prognosis, reducing morbidity, and preventing the progression to widespread, debilitating disease [6,7,9,10,13,21]. The management of PV typically requires systemic immunosuppression, and initiating treatment early can lead to better disease control and lower cumulative steroid doses, thereby minimizing the risk of severe adverse effects.Therefore, enhancing the understanding of the early clinical signs, particularly within the oral cavity, and correlating them with laboratory parameters and specific topographic distribution patterns is of utmost importance. This study aims to contribute to this understanding by investigating the clinical laboratory parameters and topographic zones of damage in patients with pemphigus, with a specific focus on its oral manifestations, to aid in earlier and more accurate diagnosis and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

2. Purpose of Our Research

- To study clinical laboratory parameters and topographic zones of damage in patients with pemphigus.

3. Research Methodology

- This study was conducted at the Tashkent Dermatovenerological Dispensary over a three-year period (2022–2025). The research included an analysis of outpatient records of patients diagnosed with various clinical forms of pemphigus.Study population and clinical manifestations. Patients presenting with blistering and erosive lesions of the skin and/or mucous membranes, clinically consistent with pemphigus, were included. Clinical manifestations such as flaccid blisters, erosions on the oral mucosa, Nikolsky’s sign, and involvement of seborrheic zones were documented.Inclusion criteria. Patients with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of pemphigus, supported by cytological findings (presence of acantholytic cells) and laboratory investigations, were included in the study.Exclusion criteria. Patients with other autoimmune bullous dermatoses (e.g., bullous pemphigoid, mucous membrane pemphigoid), severe systemic illness interfering with study participation, or incomplete medical rec.Ethical considerations. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Local Ethical Committee of the Tashkent Dermatovenerological Dispensary. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion.Data collection. Clinical interviews, physical examinations, dental status assessment, and evaluation of Nikolsky’s sign were performed. Laboratory investigations included:- Cytological examination (smear impressions from erosions for acantholytic cells),- Complete blood count,- Biochemical blood analysis (including C-reactive protein, glucose levels),- Clinical urinalysis.Topographic zones of involvement (chest, abdomen, back, anogenital region, extremities, face, scalp, lips, oral cavity, and neck) were systematically recorded.Sample type and duration. Blood, urine, and cytological smear samples were collected at initial presentation. The duration of sample collection covered the entire study period (three years).Statistical analysis. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS version XX. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, percentages) were calculated. Comparative analyses were performed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or ANOVA for continuous variables, as appropriate. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Analysis and Results

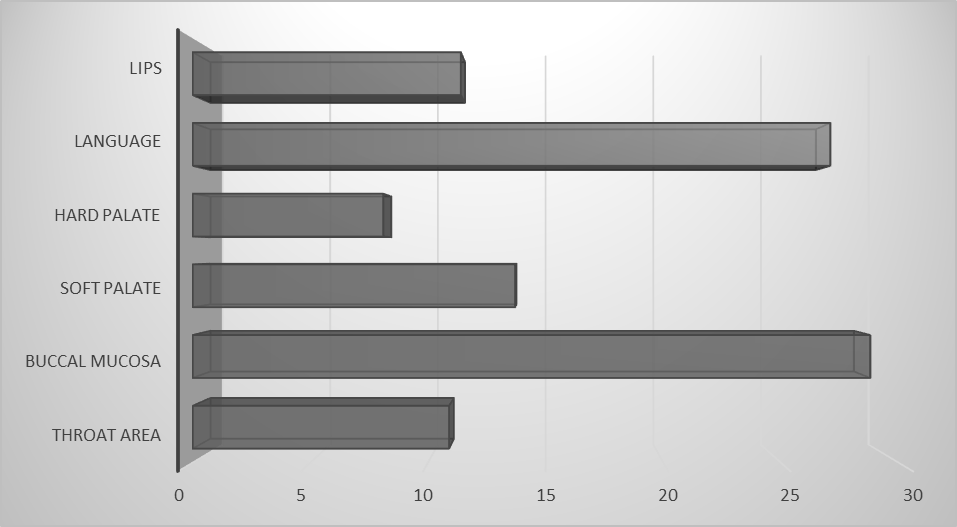

- All patients were stratified into three groups according to age and sex. In the 19–30 years’ group, pemphigus was diagnosed in 3 women; in the 30–39 years’ group, in 5 women; and in the 32–48 years’ group, in 7 patients (3 men and 4 women). The highest incidence was observed in the 46–55 years’ group, comprising 23 patients (9 men and 14 women). In the 56–69 years’ group, pemphigus was detected in 5 patients (2 men and 3 women).The most frequent clinical variant was pemphigus vulgaris, identified in 34.69% of patients, followed by the erythematous form in 31.82%. Less common manifestations included pemphigus foliaceus (9.01%) and other rare forms (4.55%).Analysis of haematological parameters showed that 91% of patients demonstrated abnormalities in leukocyte counts. Elevated leukocytes were found in 69.8% of cases, lymphocytosis in 75.9%, granulocytosis in 26.7%, and monocytosis in 64.3%. Biochemical blood analysis revealed the presence of C-reactive protein in 27.3% of patients (up to 15.9 units, whereas normally not detected) and hyperglycaemia in 31.8% (with glucose levels rising from 5.84 to 19.12 units).Urinalysis abnormalities were detected in 35.9% of patients, including increased relative density in 24.1%, glycosuria in 12.9%, and isolated cases of altered urinary medium. Tzanck cells were identified in the venous blood of 49% of patients.Topographic analysis of clinical manifestations allowed identification of 11 affected anatomical zones: chest, abdomen, back, anogenital region, upper limbs, lower limbs, face, scalp, lips, oral cavity, and neck. The distribution of lesions varied depending on the clinical form.Pemphigus vulgaris, the most common form, was characterized by thin-walled, flaccid blisters of varying size with serous contents, arising on clinically unaffected skin and on mucous membranes of the oral cavity, pharynx, and lips. Seborrheic (erythematous) pemphigus, unlike the vulgar form, typically began with lesions on seborrheic regions of the face, back, chest, and scalp (Figure 1). Pemphigus foliaceus presented with erythematous-squamous eruptions and recurrent thin-walled blisters, which upon rupture exposed erosions followed by the formation of lamellar crusts; mucosal involvement was uncharacteristic. Pemphigus vegetans was observed as a localized, relatively benign process persisting for years when the general condition of the patient remained satisfactory.

| Figure 1. Localization of pemphigus in the mucous membrane mouth |

5. Conclusions

- The present study demonstrated that pemphigus occurs more frequently among women than men, with the highest incidence observed in the 46–55 age group. Pemphigus vulgaris was the most common clinical form, followed by erythematous pemphigus. Labora-tory analyses revealed abnormalities in hematological, biochemical, and uri-nary parameters, supporting the sys-temic nature of the disease. The detec-tion of acantholytic (Tzanck) cells fur-ther confirmed the diagnosis in the majority of cases.The study highlights the importance of early clinical recognition and labora-tory confirmation for accurate diagno-sis and timely management. However, the limited sample size and single-center design may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Further multi-center studies with larger cohorts are recom-mended to validate and expand upon these results.

Study Limitations

- No significant limitations were identified in the present study. All procedures were conducted under standard conditions, and the study sample was representative of the target population. However, further research with larger and more diverse samples is recommended to validate and expand upon these findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors declare that there are no acknowledgments for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML