-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(9): 2958-2963

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251509.24

Received: Aug. 20, 2025; Accepted: Sep. 8, 2025; Published: Sep. 20, 2025

Tension-Type Headache: Diagnosis and the Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Turakulova Diyora1, Mirdzhuraev Elbek1, Adambaev Zufar2, Ravshan Olmosov3

1Center for the Development of Professional Qualification of Medical Workers, Department of Neurorehabilitation, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Urgench Branch of Tashkent Medical Academy, Urgench, Uzbekistan

3Kimyo International University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Ravshan Olmosov, Kimyo International University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The article analyzes diagnostic approaches and treatment effectiveness in tension-type headache (TTH). A total of 101 patients aged 22-43 years were divided into three groups: drug therapy only, drug therapy with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and drug therapy with biofeedback (BFB). Pain intensity, anxiety, depression, and quality of life were assessed. All groups showed improvement, but the best results were achieved with BFB, which significantly reduced pain and emotional disturbances and improved quality of life compared to CBT and drug therapy alone.

Keywords: Tension-type headache, Diagnosis, Treatment principles, Prevention, Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Biofeedback therapy

Cite this paper: Turakulova Diyora, Mirdzhuraev Elbek, Adambaev Zufar, Ravshan Olmosov, Tension-Type Headache: Diagnosis and the Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 9, 2025, pp. 2958-2963. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251509.24.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Tension-type headache (TTH) is one of the most common disorders, affecting a significant proportion of the world’s population. Over 1.5 billion people experience periodic headaches [20,23]. In 24-37% of people, TTH occurs several times a month, approximately 10% suffer from weekly attacks, and 2-3% of the population experience the chronic form (CTTH) [20,23].According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (3rd edition, 2013), depending on the frequency of headache (HA) occurrence, there are three main types of TTH [24]:Infrequent episodic TTH: less than 1 day per monthFrequent episodic TTH: from 1 to 14 days per monthChronic TTH: more than 15 days per monthThis classification is based not only on episode frequency but also on significant differences in pathogenesis, impact on daily life, and treatment approaches [1-6].Each form of TTH is further divided into two subtypes:with involvement of pericranial muscles;without involvement of pericranial muscles [1-6].Typical symptoms of TTH include bilateral, mild to moderate pain in the frontal-temporal region, described as pressing, non-pulsating, and accompanied by other sensations. Patients often describe it as “dull”, “aching”, “heaviness in the head”, “a tight cap”, “a band squeezing the head” or “pressure on the head, neck, and shoulders”. In rare cases, TTH may be unilateral or pulsating.Additional studies - such as laboratory tests, functional diagnostics, and neuroimaging - usually show no abnormalities in TTH and are not required with a typical clinical presentation [1-9]. On examination, palpation often reveals increased muscle tension around the head and neck, tenderness of pericranial muscles, and myofascial trigger points. There is a correlation between muscle tension/tenderness and the frequency/intensity of TTH attacks, which worsens during exacerbations [12-16,18,21,22,25].Main clinical signs requiring detailed diagnostic evaluation in non-acute headaches:1. Unexplained abnormalities in neurological status.2. Atypical headache course, especially with progressive patterns of cephalalgia.International Standards and Recommendations for Treating TTHThe “gold standard” for TTH treatment is an individualized, comprehensive approach, including three main directions [1,2]: non-drug therapy; pharmacotherapy for headache episodes; preventive treatment for frequent and chronic forms of TTH.In the initial treatment of patients with frequent and chronic TTH, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) plays a key role. From the first consultation, it is important to explain the benign nature of the condition, identify causes and triggers, highlight the impact of psychoemotional state, muscle tension, daily routine, and stress, and set treatment goals, including lifestyle normalization (sleep, nutrition, hydration, physical activity) [1,2,8,9].Non-drug approaches. Most TTH patients improve with non-drug measures such as sleep hygiene, regular exercise, proper nutrition, trigger avoidance, relaxation techniques, biofeedback (BFB), and CBT. Clinical observations and controlled trials show the effectiveness of EMG biofeedback.Unfortunately, in many countries, both doctors and patients tend to prefer medications, underestimating behavioral therapy. CBT, BFB, and relaxation are effective preventive methods for TTH, widely used in specialized clinics. Behavioral therapy is important not only for preventing attacks but also for managing them when they occur. Active patient participation increases treatment effectiveness.Passive methods such as massage, physiotherapy, and acupuncture lack strong evidence for TTH and do not teach patients pain self-control; therefore, they are not considered modern therapy of choice [1,2,8,9].CBT’s effectiveness is comparable to pharmacotherapy, as shown in meta-analyses. Combining behavioral therapy with drug therapy increases treatment efficacy, and adding behavioral methods to preventive pharmacotherapy helps maintain the effect after drug withdrawal.Relaxation skills acquired through behavioral therapy reduce TTH frequency and analgesic use. Studies confirm the benefit of combining CBT with biofeedback.Persistent pain leads to pain-related behavioral patterns, reduced work capacity, psychological discomfort, and possible psychiatric disorders - problems that CBT addresses [1,2,8,9].CBT is effective because it teaches patients pain management techniques, emotional regulation, and conscious lifestyle changes. It also significantly increases adherence to non-drug recommendations (sleep, diet, exercise, relaxation techniques) and reduces stress levels associated with TTH.Frequent TTH episodes increase the risk of analgesic overuse and medication-overuse headache (MOH). Therefore, psychotherapeutic methods - especially CBT are recommended as an alternative or adjunct to drug therapy in patients with three or more attacks per month [1,2,8,9].Main recommendations for symptomatic TTH therapy [11,17,19]:1. Use analgesics early in the TTH episode. Increasing pain intensity reduces analgesic effectiveness and may require higher doses.2. Individually select the dose. In most cases, maximum initial doses are recommended to prevent headache recurrence and repeated medication use. If low doses are effective for a patient, the dose should only be increased if efficacy decreases.3. Fast-acting forms (e.g., rapid-release ibuprofen 400 mg) provide high efficacy with lower total doses.4. When headache frequency increases - especially in CTTH with comorbid psychoemotional disorders-analgesic effectiveness declines. Preventive therapy is then recommended.To prevent MOH, the use of analgesics should be strictly limited:Barbiturate-containing medications - no more than 3-4 times per monthTriptans - no more than 9 times per monthSimple analgesics and NSAIDs - no more than 15 doses per monthAs first-line agents for stopping a TTH attack, common analgesics such as acetaminophen and acetylsalicylic acid are used, as well as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and naproxen.Currently, there is no convincing evidence supporting the effectiveness of muscle relaxants in the treatment of TTH; therefore, their use for acute attack management is not recommended.Main causes of ineffective therapy [1,2,8,9]:1. Incorrect TTH diagnosis. At least two scenarios are possible:Most often, a TTH diagnosis is mistakenly given to patients with migraine without aura. Misdiagnosis is generally related to a superficial patient interview.Much less frequently, secondary headache may present under the guise of TTH, which requires thorough examination to clarify the true cause of cephalalgia.2. Incorrect pharmacotherapy selection: low doses, late administration of the drug at the peak of headache intensity, or individual drug intolerance.3. Low analgesic effectiveness in TTH may be associated with the chronic nature of TTH and the development of medication-overuse headache (MOH). In such cases, the first step is to discontinue the overused drug and start preventive treatment.4. Unrealistic patient expectations (e.g., complete headache relief within 5 minutes of taking the medication), pronounced comorbid psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety disorders).The main goals of preventive treatment are [4,10]:reducing headache frequency, duration, and intensity;improving the effectiveness of symptomatic analgesic therapy;restoring daily activity and quality of life.Before starting preventive pharmacotherapy, it is important to ensure that non-pharmacological methods have proven insufficient. This is critically important, as studies show that behavioral approaches, relaxation techniques, psychological counseling, and especially EMG biofeedback (BFB) often demonstrate effectiveness comparable to a course of antidepressants.Given the frequent coexistence of TTH with anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and depression, the choice of preventive therapy should take comorbidities into account. Antidepressants (such as amitriptyline, mirtazapine, and venlafaxine) are first-line agents, while the evidence base for anticonvulsants (topiramate, gabapentin), muscle relaxants (tizanidine), and botulinum toxin type A is less convincing [1,2,6,8,9,11].Topiramate (100 mg/day in two divided doses), gabapentin (1600-2400 mg/day), and tizanidine (4-12 mg/day) can be considered as alternative preventive agents when antidepressants are ineffective or poorly tolerated. However, botulinum toxin type A is currently not approved for TTH prevention. Amitriptyline shows the greatest efficacy in chronic TTH. It is recommended to use the minimal effective dose (30-75 mg/day), selected individually for each patient [1,2,6,8,9,11].According to the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS), mirtazapine (30 mg) and venlafaxine (150 mg) are considered second-line drugs [26].Clinical experience and current evidence indicate the ineffectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in chronic TTH. However, they may be used for treating comorbid anxiety-depressive disorders in patients with TTH.Ineffectiveness of CTTH treatment is often associated with incorrect pharmacotherapy, use of subtherapeutic doses, short treatment courses, and rapid dose escalation. These errors lead to a lack of therapeutic effect, adverse drug reactions, and treatment discontinuation. Therefore, effective and safe antidepressant use requires strict adherence to the following principles [1,2,6,8,9,11]:1. Start with the lowest dose, gradually increasing until clinical improvement, and individually select the minimal effective dose (e.g., amitriptyline - starting dose 10-12.5 mg in the evening before sleep, increasing by 10-12.5 mg every 2-3 weeks until significant clinical improvement is achieved).2. Adhere to treatment duration (generally at least 6 months). It is important to note that improvement may occur only after 4-6 weeks of treatment and continue to increase over 3 months.3. If MOH is present, complete withdrawal of the overused drug and overall limitation of analgesic intake are essential; otherwise, preventive therapy will be ineffective.4. Use headache diaries for treatment evaluation and follow-up.5. Gradually discontinue therapy.Treatment and prevention of TTH is a complex task requiring the involvement of specialists from various fields and an approach aimed at correcting not only physical but also psychological aspects. Non-pharmacological treatment methods play a particularly important role in this process. Only a comprehensive approach that takes into account all aspects of a patient’s life can effectively reduce the frequency and severity of TTH episodes and normalize daily functioning.Treatment should be individualized, taking into account such factors as age, sex, metabolic characteristics, comorbidities, endocrine disorders, comorbid psychiatric conditions, history of medication overuse, and interpersonal relationship patterns.Based on the literature reviewed, our aim was to conduct a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of various types of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with TTH.

2. Material and Research Methodology

- Study design and participants. A total of 101 patients with Tension-Type Headache (TTH), aged 22 to 43 years, who provided informed consent, were examined. The control group included 17 healthy individuals without headaches. Among them, there were 8 men and 9 women. The mean age of the patients was 31.6±5.4. All patients underwent a clinical-neurological examination.The duration of TTH in patients was 3.2±2.1 years. Pericranial and/or neck muscle involvement was observed in 76% of cases. Headache severity was assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the McGill Pain Questionnaire. Quality of life (QoL) was evaluated using an appropriate questionnaire (score range 1-100), anxiety level by the Spielberger test (score>45 - high anxiety), and depression severity by the Beck test (score>16 - high depression) [9].Three groups of TTH patients were studied, differing in therapy methods:Group 1: 35 patients receiving drug therapy only.Group 2: 35 patients receiving drug therapy + CBT.Group 3: 31 patients receiving drug therapy + BFB training.The core of cognitive-behavioral therapy is identifying and eliminating situations of chronic stress. A key part of treatment is explaining to the patient the nature of TTH, including the role of emotional factors and overstrain of pericranial muscles. Therefore, essential therapy components include: eliminating TTH triggers, adhering to dietary regimen and sleep hygiene, rational distribution of physical, mental, and emotional loads, regular recreational sports activities, and training in psychological and muscular relaxation techniques [3,8,10].For each patient in the EEG-BFB group, 10 sessions of biofeedback training using the EEG-α protocol were conducted with the “BOS Reakor” device. The effectiveness of BFB was monitored by assessing the bioelectrical activity of the brain during the first and final sessions. EEG was recorded during a state of relaxed wakefulness with eyes closed using the EEG A-21/26 “Encephalan-131-03” device in a monopolar montage (with auricular reference electrodes) from 16 standard leads positioned according to the international 10-20 system, within the frequency range of 1-35 Hz. The effectiveness of EEG-BFB therapy was evaluated based on the increase in α-activity.General criteria for the effectiveness of CBT and EEG-BFB training included the reduction in TTH intensity and improvement of the overall mental state (according to psychometric scales) and neurological status of the patients. The statistical significance of differences between groups for each treatment efficacy parameter was determined using statistical methods.

3. Research Results

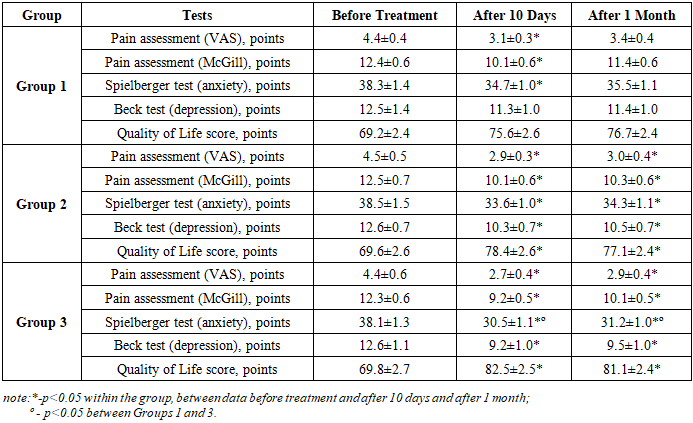

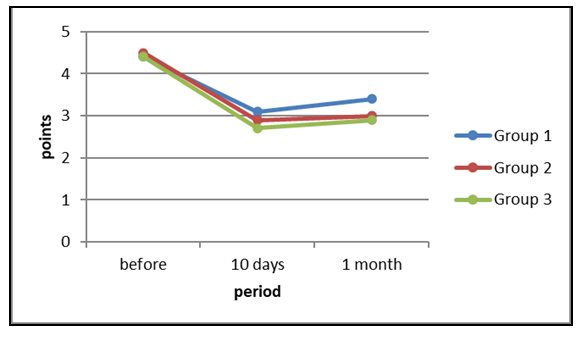

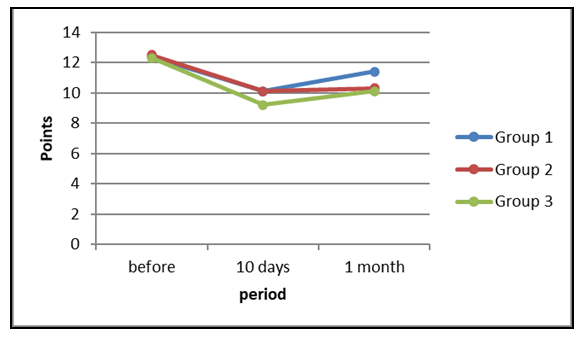

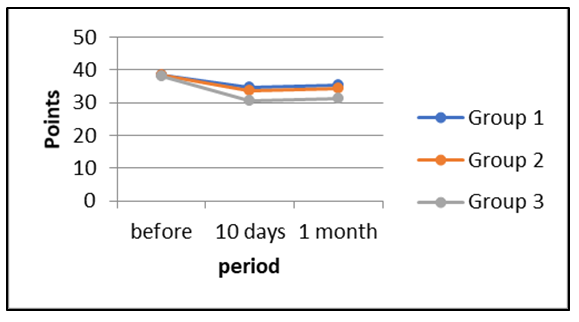

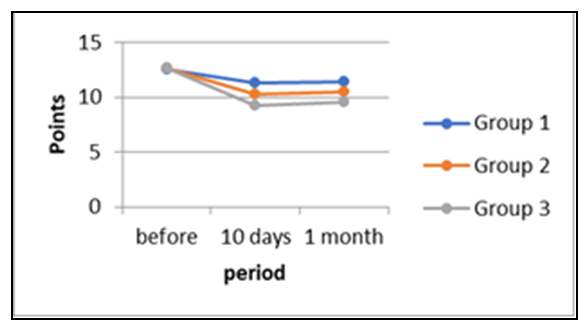

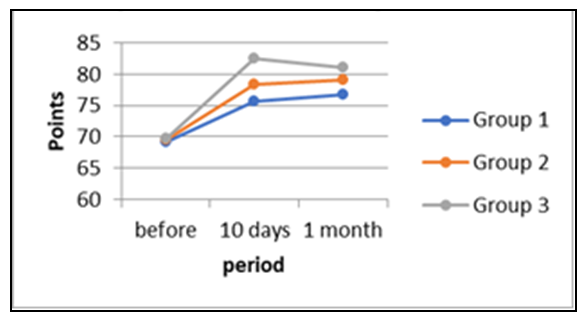

- The duration of TTH in patients was 3.2±2.1 years. Involvement of pericranial and/or cervical muscles was observed in 88% of cases. Headache severity, as measured by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), was 4.4±0.4 points. Pain intensity on the McGill Pain Questionnaire was 12.4±0.6 points. Quality of life (QoL) score averaged 69.2±2.4 points. Anxiety severity according to the Spielberger test was 38.3±1.4 points, while depression severity according to the Beck test was 12.5±1.4 points. In Group 1 patients, rational use of medications for TTH was explained.In Group 2, in addition to rational medication use, patients underwent cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). In Group 3, alongside rational medication use, patients completed 10 sessions of biofeedback (BFB) training. As a result of the treatment, we evaluated the comparative dynamics of test scores in the groups before and after therapy (Table 1).

|

| Figure 1. Dynamics of pain intensity according to the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) in groups |

| Figure 2. Dynamics of anxiety according to the McGill scale in groups |

| Figure 3. Dynamics of anxiety according to the Spielberger scale in groups |

| Figure 4. Dynamics of depression according to the Beck scale in groups |

| Figure 5. Dynamics of quality of life (SF-36) in groups |

4. Discussion

- The conducted research indicates that rational use of pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and biofeedback (BFB) therapy for tension-type headache (TTH) had an overall beneficial effect on patients. Across all study groups, there was a statistically significant reduction in pain intensity (p<0.05), a decrease in depression and anxiety levels (p<0.05), and an improvement in patients’ quality of life (p<0.05). The most pronounced improvements were observed in patients who received BFB therapy.Following the course of BFB therapy, a marked positive dynamic was recorded, which may indicate a change in the reactivity level of regulatory structures. This included a decrease in the excitability of the nociceptive system in patients with TTH who underwent BFB sessions. One of the outcomes of BFB training was the development of the ability to enter a psychophysiological state in which heart rate normalization occurred. During the study, it was established that successful completion of training tasks during the sessions led to improved general well-being, enhanced psychological state, and elevated mood, owing to the awareness of personal achievement-effects that were reflected in the measured indicators.Thus, the application of two different methods-CBT and BFB training-in patients with chronic TTH resulted in improvement of clinical parameters, reduction in pain intensity, and better neurological and psychological status. A comparison of the two interventions demonstrated that BFB therapy was more effective than CBT in patients with TTH.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors express their gratitude to the staff of department of Neurorehabilitation of Center for the development of professional qualification of medical workers in helping to select patients for diagnosis; to basical doctorant student D. Turakulova and to R. Olmosov for actively help in collecting data and for helping in all processes of research; to the Head of the “General Med Standart” clinic, MD Z. Adambayev for writing an article; to head of the department of Neurorehabilitation, of Center for the development of professional qualification of medical workers professor E.Mirdzhuraev for editing an article. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest when writing this article. The work was carried out within the framework of the dissertation work. When carrying out scientific work, own funds were attracted.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML