Amriddinova Farangiz Shaxobiddinovna, Madjidova Yakutkhon Nabiyevna, Jo‘rayeva Gulshakar Tillo qizi

Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

This article examines the clinical and neurological features of polyneuropathy associated with coronavirus infection (COVID-19). The study analyzes symptoms, the severity of neurological impairments, and their progression depending on the severity of the infection. Special attention is given to the severity of sensorimotor disturbances, the extent of peripheral nervous system involvement, and the correlation with psycho-emotional disorders.

Keywords:

COVID-19, Polyneuropathy, Neurological manifestations, post-COVID syndrome, ENMG

Cite this paper: Amriddinova Farangiz Shaxobiddinovna, Madjidova Yakutkhon Nabiyevna, Jo‘rayeva Gulshakar Tillo qizi, Clinical and Neurological Features of Polyneuropathy of Coronavirus Etiology, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 7, 2025, pp. 2303-2308. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251507.46.

1. Introduction

A review of current literature indicates that COVID-19 is not merely a form of pneumonia, but a systemic disease associated with numerous complications. In addition to common symptoms such as fatigue and shortness of breath, patients often experience panic attacks, central nervous system involvement, male reproductive dysfunction, and other issues [2,3]. According to a study conducted in Rome, among 143 hospitalized COVID-19 patients aged 19 to 84, only 12.6% had no symptoms two months after disease onset. About 32% reported one to two symptoms, and 55% experienced more than three symptoms. Furthermore, 44.1% reported a decreased quality of life, and more than half complained of persistent fatigue [2]. One of the complications of COVID-19 is polyneuropathy [4]. The most commonly used international scales for assessing neuropathy severity range from grade 0 (mild) to grade 4 (life-threatening or associated with physical disability and cognitive impairment) [5]. Grade 2 indicates functional impairment, while grades 3 and 4 signify significant deterioration in daily life quality (J. Majersik, V. Reddy, 2020; O. Koyuncu, I. Hogue, I. Enquist, 2020). Symptoms of polyneuropathy may appear suddenly or develop gradually, eventually becoming chronic, depending on the underlying cause. Since the pathophysiology and clinical presentation of the disease are closely interconnected, polyneuropathies are typically classified by the primary site of damage: 1. Myelin., 2. Nerve vasculature., 3. Axon. Demyelinating polyneuropathies most often result from a parainfectious immune response triggered by encapsulated bacteria, viruses, or vaccination [6].Research Objective. To evaluate the clinical and neurological features of polyneuropathy of coronavirus etiology and to determine the effectiveness of acupuncture therapy as part of the comprehensive rehabilitation of patients.

2. Materials and Methods

To address the stated objectives, we examined 95 patients diagnosed with polyneuropathy of coronavirus etiology and diabetic polyneuropathy. The study was conducted at the Department of Neurology and Pediatric Neurology of the Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute and the "Neuromed Service" clinic from 2020 to 2024. Among the total number of observed patients, 56.7% were male and 43.3% were female. The age range of the patients was between 45 and 60 years, with a mean age of 54.07 ± 1.12 years. All patients underwent a comprehensive examination according to a unified protocol, which included both somatic and detailed neurological assessments based on standard methodology.Inclusion CriteriaParticipants were included in the study based on the following criteria:– A confirmed history of coronavirus infection in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10 code U07.1;– Male and female patients aged 19 to 60 years who had experienced various forms of inflammatory polyneuropathy associated with COVID-19 (U07.1);– Absence of severe chronic infectious or somatic diseases, intellectual disabilities, or major organic brain disorders;– Written informed consent to participate in the study.Exclusion CriteriaPatients were excluded from the study based on the following criteria:– Age under 19 years;– Legal incapacity, coexisting neurological or psychiatric disorders, oncological conditions, or chronic somatic diseases;– Patient refusal to participate or absence of written informed consent.

3. Study Results

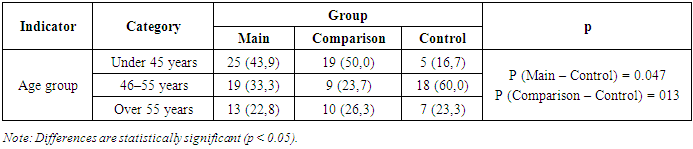

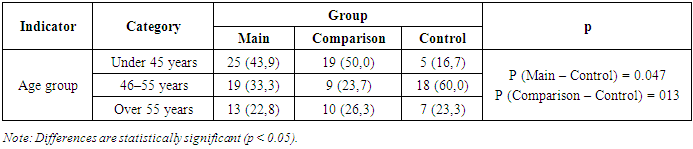

A total of 95 patients aged 35 to 65 years who received inpatient treatment at the Neuromed Center were observed in this study. According to the study design, participants were divided into three groups:• Group I – Main Group: 57 patients (45.6%) diagnosed with polyneuropathy of coronavirus etiology;• Group II – Comparison Group: 38 patients (30.4%) diagnosed with diabetic polyneuropathy;• Control Group: 30 individuals (24.0%) with no clinical signs of polyneuropathy.Age distribution of the patients was as follows:• Under 45 years: 44 patients (46.3%);• Aged 46–55 years: 28 patients (29.4%);• Over 55 years: 23 patients (24.2%) (Table 1).Table 1. Distribution of Patients by Age and Group

|

| |

|

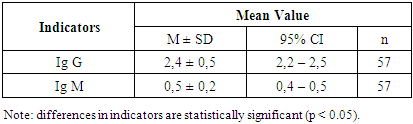

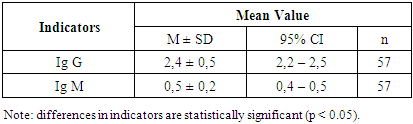

Among patients in the main group (with polyneuropathy of coronavirus etiology), the disease duration was 6 months in 27 patients (47.4%) and 1.5 years in 30 patients (52.6%). To evaluate the immune status of patients with coronavirus- related polyneuropathy and to monitor normalization of its indicators under the influence of therapeutic interventions used in the study, levels of immunoglobulins of classes M and G were assessed (Table 2).Table 2. Analysis of Humoral Immunity Indicators in Patients with Post-COVID Polyneuropathy by Group

|

| |

|

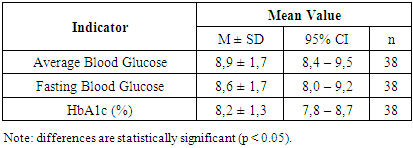

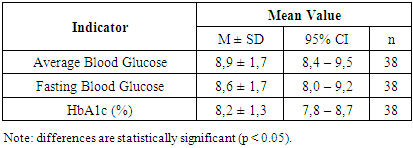

According to the results, the serum concentration of IgM (reference range = 0.4–2.3 g/L) in the patients was generally within normal limits, averaging 0.5 ± 0.2 g/L.The concentration of IgG in the blood (reference range: 7–16 g/L) was significantly decreased—2.4 ± 0.5 g/L, suggesting an attenuated humoral immune response at this stage of the disease. This reflects the immune system’s adjustment following acute inflammation. In contrast, IgM levels remained within the reference range—0.5 ± 0.2 g/L, supporting the notion of an adequate, active anti-infective response, particularly during the early contact with the infectious agent. It is currently established that acute inflammatory responses are characterized by elevated levels of both IgG and IgM compared to baseline. Increased IgM concentrations typically indicate an initial encounter with a pathogen and reflect ongoing immune activity.To assess carbohydrate metabolism parameters in 38 patients with diabetic polyneuropathy, we measured HbA1c and fasting blood glucose levels in serum (Table 3).Table 3. Glycemic Control in Patients with Diabetic Polyneuropathy

|

| |

|

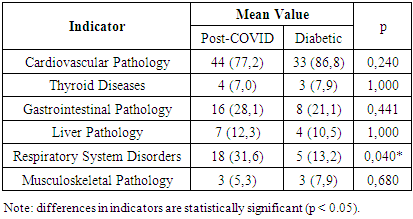

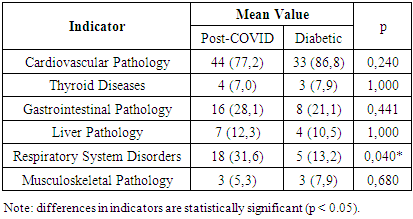

The analysis showed that the mean fasting blood glucose level was 8.6 mmol/L, and the mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 8.2%. According to our data, none of the patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus achieved the target glycemic control, while most patients (based on questionnaire data) had a history of severe hypoglycemia episodes, and one-third experienced diabetic ketoacidosis. These factors may increase the risk of developing cognitive impairments.When analyzing comorbidities by group (see Table 4), cardiovascular diseases were the most frequently observed in both groups, predominating significantly in Group II patients at 86.8%. Gastrointestinal pathology was more commonly found in Group I patients (28.1%). Respiratory system disorders were significantly more frequent in patients with coronavirus-associated polyneuropathy (31.6%). In addition to these, thyroid diseases, liver pathology, and musculoskeletal disorders were detected in patients from both groups (Table 4).Table 4. Analysis of Comorbidities by Group

|

| |

|

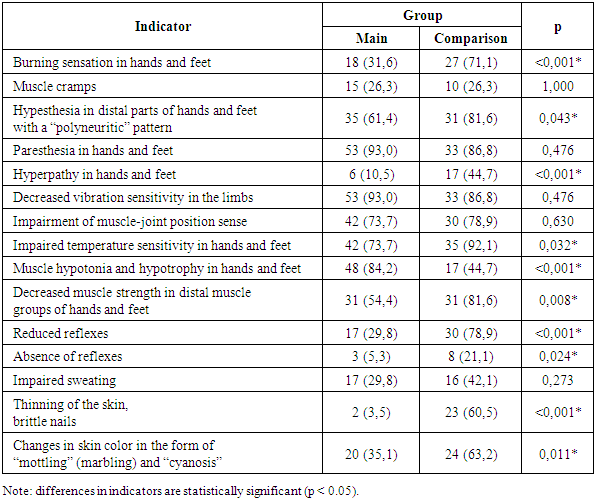

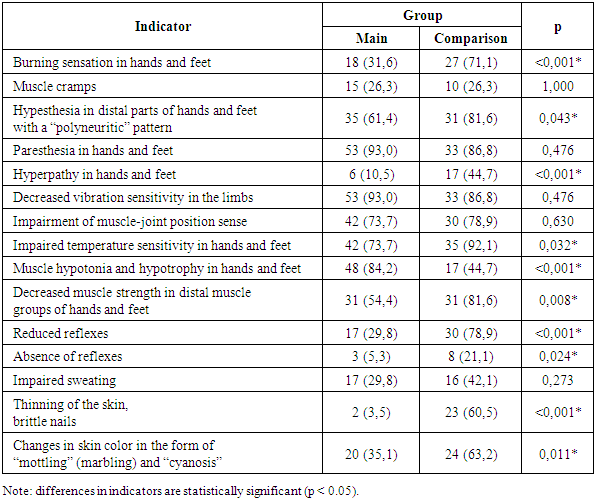

The assessment of complaints by patient groups, presented in Table 5, indicated pathological processes occurring at the level of the peripheral nervous system. The most frequently reported complaints were: burning sensations in the hands and feet, predominantly in the comparison group – 27 patients (71.1%);Hypesthesia in the distal parts of the hands and feet, following a “polyneuritic” pattern, significantly more common in Group II patients – 31 patients (81.6%);Paresthesia in the distal limbs, predominantly in the main group – 53 patients (93.0%).Table 5. Frequency of Reported Complaints in Patients with Polyneuropathies Across Examined Groups

|

| |

|

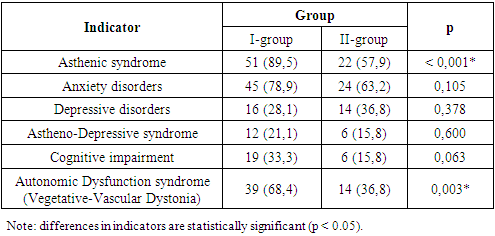

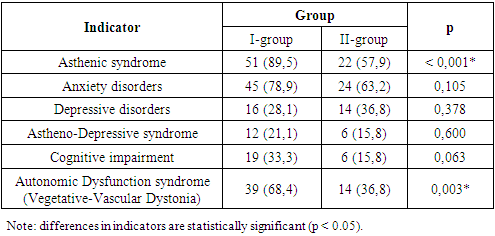

During the clinical neurological examination of patients, various clinical syndromes of functional brain insufficiency were identified in both patient groups (Table 6).Table 6. Analysis of Cerebral Syndromes by Group

|

| |

|

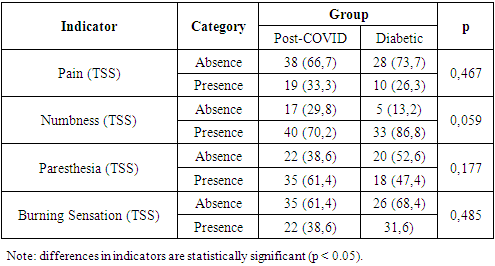

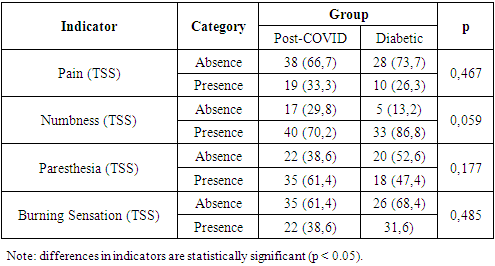

The most frequent manifestation was the asthenic symptom complex, observed in Group I in 89.5% of cases and in Group II in 57.9% of cases. Its characteristic features included excessive fatigue, decreased work capacity, as well as reduced concentration and productivity of intellectual activity. The autonomic dysfunction syndrome (vegetative-vascular dystonia) was noted in 68.4% of patients in Group I and 36.8% in Group II. Anxiety disorders, characterized by increased personal and situational anxiety, were found in 78.9% of patients with coronavirus-associated polyneuropathy and 63.2% of patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Astheno-depressive syndrome was detected in 21.1% of cases in Group I and 15.8% in Group II. Patients in this category showed marked fatigue accompanied by sharply lowered mood, social withdrawal, passivity, and a tendency toward isolation. They were generally monosyllabic in responses to questions. Cognitive dysfunction syndrome was identified in 33.3% of patients with coronavirus-associated polyneuropathy and 15.8% of patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Typical features included decreased attention span and memory impairment. Thus, the identified syndromes suggest that the fundamental basis of these changes in both groups is disorders of the integrative activity of the brain, reflecting functional impairments within structures of the limbic-reticular complex. In our study, the Total Symptom Score (TSS) diagnostic scale was used to assess the severity of “positive” polyneuropathic symptoms. Table 7 presents the frequency and severity of neuropathic complaints in the study cohort. We found that numbness in the feet was the most common complaint in both Group I and Group II patients—reported by 40 patients (70.2%) and 33 patients (86.8%), respectively.Table 7. Analysis of Total Symptom Score (TSS) by Patient Group

|

| |

|

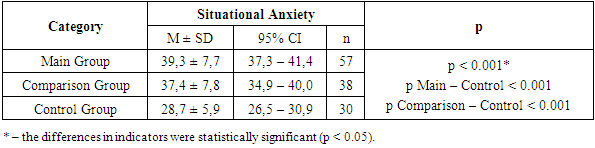

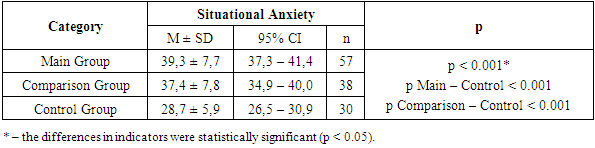

Patients in both study groups frequently reported paresthesia in the lower limbs—35 (61.4%) in Group I and 18 (47.4%) in Group II. Burning sensations in the feet were observed in 22 (38.6%) patients in the first group and 12 (31.6%) in the second group. Complaints of pain were reported by 19 (33.3%) and 12 (31.6%) patients, respectively, with its intensity assessed as moderate on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS): Group I scored 6.8 ± 1.6 points and Group II scored 5.3 ± 1.4 points.At the time of examination, patients in both groups reported psychological disturbances of varying severity, such as emotional lability, irritability, tearfulness, and feelings of unjustified anxiety. To assess anxiety levels in these patients, we conducted an analysis of situational and trait anxiety using the Spielberger-Hanin methodology.The anxiety assessment revealed a moderate level of situational anxiety (SA) in the main group (post-COVID polyneuropathy) with a mean score of 39.3 ± 7.7 points, and a similar moderate level in the comparison group (diabetic polyneuropathy) with 37.4 ± 7.8 points. In the control group, anxiety levels were between “no anxiety” and “low situational anxiety,” scoring 28.7 ± 5.9 points (Table 8).Table 8. Analysis of Situational Anxiety Depending on the Group

|

| |

|

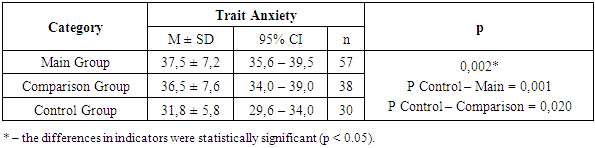

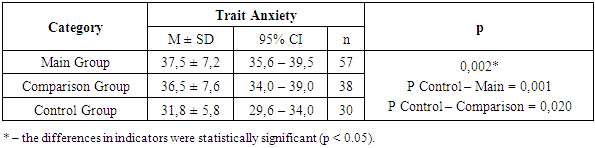

A similar pattern was observed in the assessment of trait anxiety (TA). In the group of patients with polyneuropathy of coronavirus etiology and in the group with diabetic polyneuropathy, the severity of trait anxiety corresponded to a moderate level – 37.5 ± 7.2 and 36.5 ± 7.6 points, respectively. In the control group, this indicator was at the borderline between low and moderate levels of TA – 31.8 ± 5.8 points (Table 9).Table 9. Trait Anxiety Depending on Group Affiliation

|

| |

|

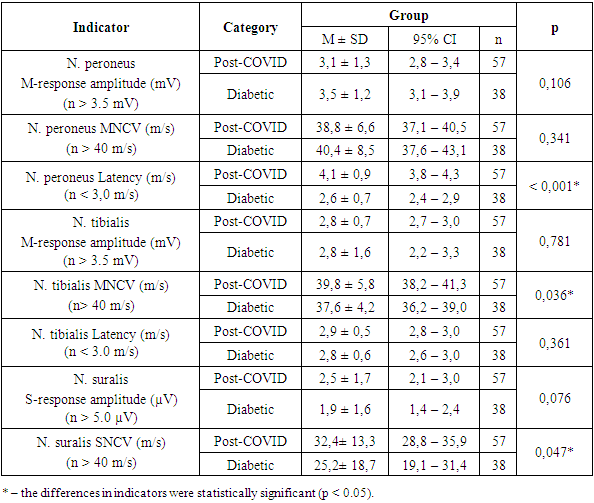

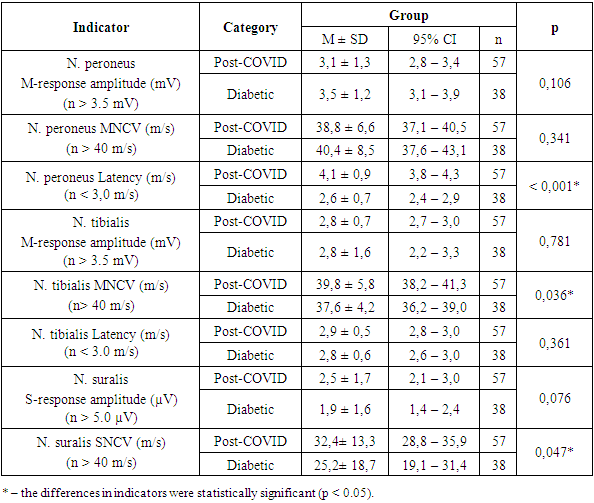

Thus, both situational (state) and trait anxiety were detected in all examined patients, i.e., in the main and comparison groups. A comparative analysis of the severity of changes in various EMG indicators depending on the patient group showed that the neurological deficit inherent to these forms of polyneuropathy was accompanied by alterations (or values close to the normal range) in the functional state of motor and sensory nerves (Table 10).Table 10. EMG Analysis of Lower Limbs by Group

|

| |

|

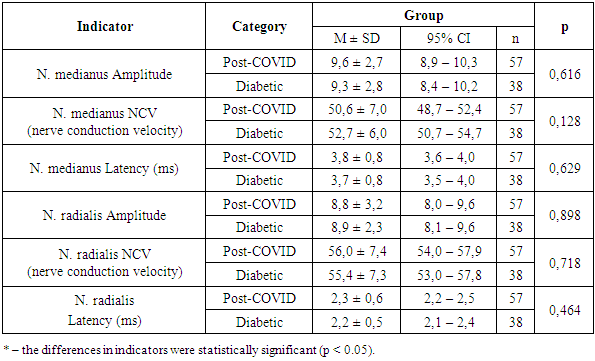

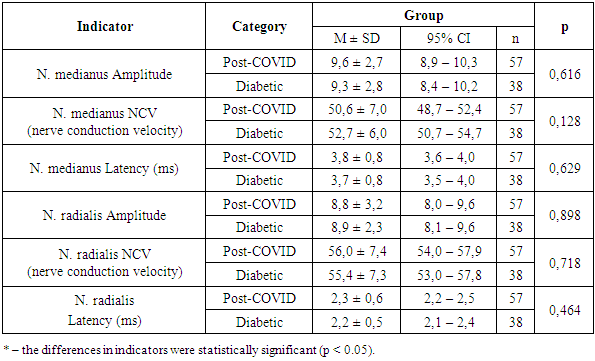

Thus, based on the study results, characteristic features inherent to this category of patients can be noted. Specifically, at the initial stage of development of both diabetic and post-COVID polyneuropathies, the greatest reduction occurs in the amplitude of the sensory response of the sural nerve. With further worsening of clinical symptoms, there is a significant decrease in the amplitude and M-response of the peroneal and tibial nerves.Electromyographic examination of the upper limbs generally did not reveal significant changes; deviations were observed only in the latency of the median nerve — 3.8 ± 0.8 ms and 3.7 ± 0.8 ms, respectively (Table 11).Table 11. EMG Analysis of the Upper Limb by Group

|

| |

|

Thus, EMG results revealed symmetrical deviations in the parameters: increased latency period, decreased nerve conduction velocity (NCV) in sensory fibers, and reduced M-response amplitude in motor fibers of the distal segments of the median, peroneal, and tibial nerves. These findings indicate a mixed type of peripheral nerve damage, characterized by primary demyelination and secondary axonal degeneration. More pronounced changes were observed in the sensory fibers of the nerves in the lower limbs, which confirmed the clinical research data.

4. Conclusions

Thus, when comparing the results of clinical neurological, neuropsychological, and neurophysiological studies, we found almost identical impairments in both patient groups, reflecting pathological processes occurring at the level of the peripheral nervous system.

References

| [1] | Amriddinova, F. Sh., & Madjidova, Ya. N. (n.d.). Osobennosti kliniko-nevrologicheskikh proyavleniy polineyropatii koronavirusnoy etiologii i rol’ iglorefleksoterapii [Features of clinical and neurological manifestations of coronavirus-associated polyneuropathy and the role of acupuncture therapy]. Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute. |

| [2] | Zhu, N., Zhang, D., Wang, W., et al. (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(8), 727–733. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. |

| [3] | Chan, J. F., Yuan, S., Kok, K. H., et al. (2020). A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission. The Lancet, 395(10223), 514–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. |

| [4] | McNamara, D. (2020). COVID-19 may trigger Guillain-Barré syndrome. Medscape Medical News. Retrieved from https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/927696. |

| [5] | Majersik, J., & Reddy, V. (2020). Peripheral neuropathy. In StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448088/. |

| [6] | Burlina, A. P. (2011). Peripheral neuropathies: Classification, diagnosis, and management. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System, 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00320.x. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML