-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(7): 2192-2194

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251507.21

Received: Jun. 11, 2025; Accepted: Jul. 8, 2025; Published: Jul. 11, 2025

Restoration Status in the Treatment of Non-Carious Lesions Associated with Fatty Liver Disease

Akhmedov Alibek Bahodirovich

Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Akhmedov Alibek Bahodirovich, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In patients with non-carious hard tissue lesions associated with fatty liver disease, the clinical performance of restorations was assessed at multiple follow-up intervals. A comparative analysis of restoration status—using the USPHS “Alpha” rating—was carried out across these observation periods. Additionally, under a comprehensive treatment protocol, enamel acid resistance (TER-test) and salivary remineralization potential (COSRE-test) were evaluated and compared.

Keywords: Dental erosion, Non-carious lesions, Enamel acid resistance, Orthophosphoric acid etching, Composite restoration, TER-test, COSRE-test, Remineralization therapy, Marginal adaptation

Cite this paper: Akhmedov Alibek Bahodirovich, Restoration Status in the Treatment of Non-Carious Lesions Associated with Fatty Liver Disease, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 7, 2025, pp. 2192-2194. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251507.21.

1. Introduction

- It is well established that Grade II–III erosive defects of dental hard tissues necessitate restorative treatment. Because these lesions predominantly affect the anterior teeth, only light-curing composite materials are used, with acid etching of the enamel as a mandatory step (typically 5–15 seconds) [2,4].Considering that the extent of enamel erosion depends on factors such as the acid content of foods and beverages, duration of exposure, oral pH, and the mineralization status of the tooth, it is essential to determine the optimal etching time with 37 % orthophosphoric acid when restoring eroded primary teeth [1,3].To establish the proper etching duration, 22 children were enrolled 12 with healthy enamel and 12 with erosive lesions and a total of 62 tests were performed to assess enamel permeability after acid exposure. Following etching, the tooth surface was stained with a 2% aqueous methylene blue solution.

2. Materials and Methods

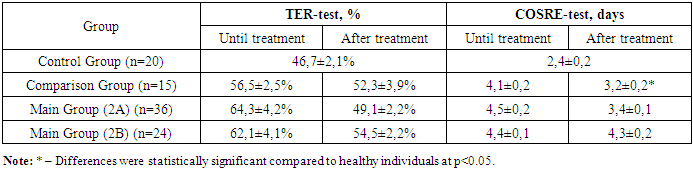

- In both healthy and eroded groups, a 2 mm-diameter drop of acid was applied to the medial segment of the vestibular surface of the central incisors for 15 seconds, and to the distal segment for 5 seconds. The acid was then rinsed off, and the tooth surface was dried. A cotton pellet soaked in 2% methylene blue was applied to the etched area for one minute. Acid resistance was evaluated by the degree of dye uptake, scored using a ten-point topographic intensity scale of blue coloration.In the healthy cohort, 5 seconds of etching prodced a mean staining intensity of 46.7±2.1%, which rose to 60.0±3.7% after 15 seconds (p<0.05). In contrast, patients with enamel erosion exhibited 68.3±4.8% staining at both 5 and 15 seconds (p>0.05).These results indicate that in teeth without pathology, staining intensity and thus acid penetration increases with longer etching times, whereas in eroded enamel the degree of penetration remains uniformly high regardless of exposure time.

3. Result and Discussion

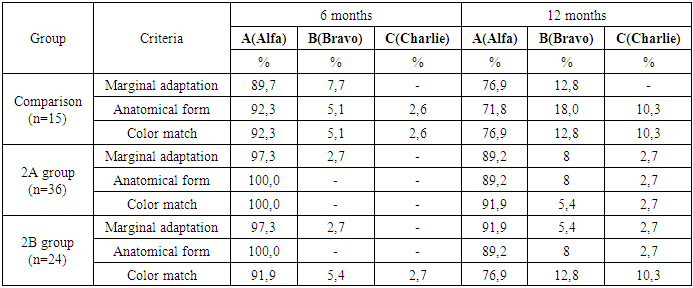

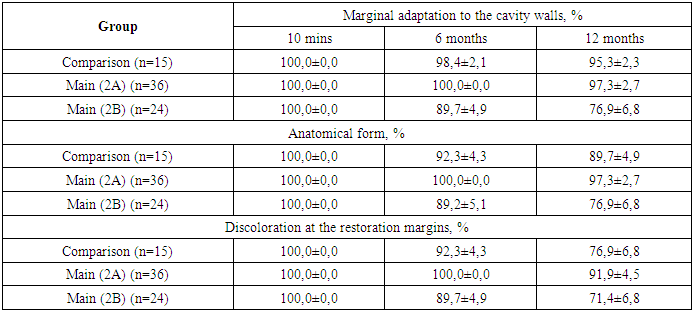

- Thus, whereas intact teeth require adherence to a 5-second etching time, in cases of enamel erosion this duration should be reduced three-fold. It is noteworthy that immediately after placement, all restorations were rated “Alpha” for marginal adaptation, anatomical form, and color match an indication of excellent initial outcomes. However, by the 6- and 12-month reviews, the clinical performance of the restorations in the study groups had changed (see Table 1).

|

|

4. Conclusions

- Thus, following the recommended methods for treating dental erosion, an increase in enamel resistance to acid and a reduction in remineralization time were observed. These positive outcomes suggest improved enamel mineralization processes in children affected by enamel erosion.

References

| [1] | Carvalho T. S., Lussi A. Susceptibility of enamel to initial erosion in relation to tooth type, tooth surface and enamel depth // Caries research. – 2015. – Т. 49. – №. 2. – P. 109-115. |

| [2] | Chun K. J., Lee J. Y. Comparative study of mechanical properties of dental restorative materials and dental hard tissues in compressive loads // Journal of dental biomechanics. – 2014. – Т. 5. – P. 1758736014555246. |

| [3] | Schlüter N. et al. Methods for the measurement and characterization of erosion in enamel and dentine // Caries research. – 2011. – Т. 45. – №. Suppl. 1. – P. 13-23. |

| [4] | Schwendicke F. et al. Managing carious lesions: consensus recommendations on carious tissue removal // Advances in dental research. – 2016. – Т. 28. – №. 2. – P. 58-67. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML