-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(7): 2170-2174

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251507.17

Received: Jun. 8, 2025; Accepted: Jul. 2, 2025; Published: Jul. 11, 2025

Chronic Renal Failure and Inflammatory Diseases of the Oral Mucosa: Immunopathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies

Sabirov Bobur Kadirbaevich, Khabibova Nazira Nasullaevna

Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Chronic renal failure (CRF) is increasingly recognized not only as a systemic disease affecting metabolic and immune homeostasis but also as a determinant of local inflammatory pathology in the oral cavity. Oral mucosal alterations, including xerostomia, candidiasis, uremic stomatitis, gingival hyperplasia, and periodontal destruction, are frequently observed in patients undergoing dialysis and post-transplant therapy. The present review synthesizes data from multiple clinical studies conducted at the Bukhara State Medical Institute, highlighting immunological disruptions, salivary dysfunction, cytokine imbalance, and mineral-bone metabolism derangements as key drivers of oral inflammation. The analysis underscores the necessity for nephrology-integrated dental care and presents biomarker-based approaches to oral diagnostics and management in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Chronic renal failure, Oral mucosa, Mucosal immunity, Xerostomia, Uremic stomatitis, Lactoferrin, IL-6, Dialysis, Immunosuppression, Nephrology-oriented dental protocols

Cite this paper: Sabirov Bobur Kadirbaevich, Khabibova Nazira Nasullaevna, Chronic Renal Failure and Inflammatory Diseases of the Oral Mucosa: Immunopathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 7, 2025, pp. 2170-2174. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251507.17.

1. Introduction

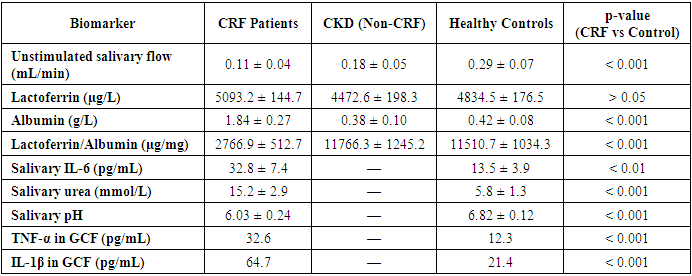

- Chronic renal failure (CRF), also referred to as end-stage renal disease, is a progressive systemic condition characterized by irreversible loss of kidney function, leading to disturbances in nitrogen metabolism, fluid and electrolyte balance, and immunological regulation. While the primary clinical manifestations of CRF are nephrological and cardiovascular, increasing evidence underscores the significant impact of CRF on the integrity and health of oral tissues. The oral cavity, as a highly vascular and immune-sensitive environment, responds dynamically to systemic changes, rendering it both a diagnostic window and a therapeutic target in patients with renal pathology [1,3].In recent decades, multiple studies—including those conducted at the Bukhara State Medical Institute—have demonstrated that patients with CRF exhibit a markedly higher prevalence of oral mucosal inflammation compared to healthy individuals or those with early-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) without renal insufficiency. This inflammation manifests in various clinical forms: xerostomia (reported in up to 78.2% of hemodialysis patients), candidiasis (over 50% prevalence in some dialysis cohorts), gingival hyperplasia, uremic stomatitis, and erosive lesions of lichen planus-like character [2,4,5].The pathophysiological basis of these manifestations is multifactorial. It includes uremic toxin accumulation in salivary secretions, local immune suppression, increased epithelial permeability, and disruption of microbiocenosis. Biochemical analysis of saliva in CRF patients reveals elevated levels of ammonia, urea (up to 15.2 ± 2.9 mmol/L), and β2-microglobulin, creating a proteolytic and pro-inflammatory environment within the oral cavity. At the same time, essential salivary components that contribute to mucosal defense, such as lactoferrin, lysozyme, and secretory IgA, are reduced or functionally impaired [3,5].Furthermore, chronic immunosuppression—whether due to the uremic state itself or post-transplant immunosuppressive therapy—exacerbates the oral inflammatory profile. Elevated concentrations of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) have been recorded in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva, correlating strongly with clinical severity and periodontal breakdown [5].Histopathological studies confirm degenerative and atrophic changes in the oral epithelium, vascular fragility, and neutrophilic infiltration. In particular, gingival tissues exhibit fibroblast hyperplasia and impaired collagen remodeling, while mucosal biopsies reveal desquamation, nuclear pyknosis, and dyskeratosis. Such findings underscore the immunopathological nature of oral diseases in CRF and challenge the conventional notion that poor hygiene alone is responsible for oral deterioration in this population [2].Despite the high clinical burden of oral lesions in CRF patients, dental care is often insufficiently integrated into nephrological protocols. There remains a notable lack of routine oral screening, targeted prophylaxis, and interdepartmental coordination between nephrologists and dental specialists. Consequently, undiagnosed mucosal inflammation may contribute to systemic infection, malnutrition, and decreased quality of life, particularly in dialysis and transplant candidates [5,6].Given these challenges, a paradigm shift is necessary in how oral manifestations of CRF are understood and managed. The present review consolidates findings from four original research studies, each exploring the immunological, biochemical, clinical, and therapeutic aspects of oral mucosal inflammation in CRF patients. By focusing on both pathogenetic mechanisms and practical treatment approaches, the article aims to provide a comprehensive framework for nephrology-integrated dental care. It emphasizes the diagnostic value of salivary biomarkers such as the lactoferrin/albumin index and IL-6 levels, the necessity of pre-dialysis dental clearance, and the role of antifungal and immunomodulatory therapies in oral rehabilitation for CRF patients [3,5].Immunopathological mechanisms and mucosal vulnerabilityThe oral mucosa serves as a first-line defense barrier, relying on an intricate network of innate immune proteins, epithelial integrity, salivary flow, and resident microbiota. In patients with chronic renal failure (CRF), this barrier becomes compromised as a result of both systemic immunosuppression and local salivary dysfunction, creating a pro-inflammatory and infection-prone environment. The immunopathogenesis of oral mucosal inflammation in CRF is multifaceted, involving quantitative and qualitative changes in immune cell populations, biochemical shifts in saliva, and disruption of cytokine signaling pathways.One of the most reliable indicators of local mucosal immunity is lactoferrin a multifunctional glycoprotein with antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. Despite its elevated absolute concentration in the saliva of CRF patients (up to 5093.2 ± 144.7 µg/L), the functional efficacy of lactoferrin is diminished when normalized against albumin levels, yielding a significantly reduced lactoferrin/albumin ratio. This index, calculated to account for salivary hypofunction, was found to be as low as 2766.9 ± 512.7 µg/mg in CRF patients, compared to 11766.3 ± 1245.2 µg/mg in CKD patients without renal insufficiency and 11510.7 ± 1034.3 µg/mg in healthy controls (p < 0.001). This dramatic decrease suggests impaired mucosal immune surveillance and vulnerability to microbial invasion.Moreover, studies report a reduction in systemic and salivary immune cells, including CD3+, CD4+ T-lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and activated macrophages in CRF patients. These changes are exacerbated by elevated serum creatinine and urea levels, which correlate inversely with immune cell function. As renal function declines, neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic capacity also deteriorate, contributing to persistent mucosal inflammation and delayed wound healing.Cytokine dysregulation represents a central mechanism of immunopathology in the oral cavity of CRF patients. Interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) are found at significantly elevated levels in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva. For instance, salivary IL-6 concentration averaged 32.8 ± 7.4 pg/mL in CRF patients with mucosal lesions—more than double that of healthy controls (13.5 ± 3.9 pg/mL; p < 0.01). These cytokines facilitate epithelial apoptosis, basement membrane breakdown, and fibroblast hyperactivity, contributing to the clinical picture of gingival hyperplasia, desquamation, and ulceration.Salivary hypofunction—defined as a reduction in unstimulated flow rate—further amplifies these immune abnormalities. Sialometric studies indicate that CRF patients produce as little as 0.11 ± 0.04 mL/min of saliva compared to 0.29 ± 0.07 mL/min in healthy individuals (p < 0.001). This deficit leads to reduced mechanical clearance, lowered pH, and diminished antimicrobial activity, providing ideal conditions for Candida albicans overgrowth and bacterial colonization by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia.Histopathologically, oral mucosa in CRF shows signs of epithelial thinning, increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and intense polymorphonuclear infiltration. Vascular alterations, including microhemorrhages and endothelial fragility, are also common and contribute to gingival bleeding and petechial eruptions. In gingival biopsies from CRF patients, prominent collagen disorganization and basement membrane damage have been reported.Interestingly, a bidirectional relationship is now recognized between oral inflammation and renal function. Persistent periodontal inflammation is thought to contribute to systemic inflammatory load, adversely affecting glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and potentially accelerating the progression of kidney disease. Elevated cytokines in the gingiva may spill over into systemic circulation, perpetuating a chronic low-grade inflammatory state a phenomenon referred to as the "oral-systemic inflammatory axis" [6,7].In summary, the immunopathogenesis of oral mucosal disease in CRF involves both systemic and local mechanisms: systemic immune cell dysfunction, elevated proinflammatory mediators, epithelial barrier breakdown, and salivary protein imbalance. The lactoferrin/albumin index and salivary IL-6 levels have emerged as promising non-invasive biomarkers for diagnosing and monitoring mucosal immune status in nephrology patients. These findings support the hypothesis that oral lesions in CRF are not merely sequelae of poor hygiene or local infection, but rather manifestations of a distinct immunopathological process requiring targeted, systemic-informed intervention.Clinical and microbiological characteristics of oral mucosal inflammation in CRFPatients with chronic renal failure (CRF) exhibit a broad and complex spectrum of oral mucosal lesions that reflect the systemic immunometabolic dysregulation inherent to advanced kidney disease. The prevalence and clinical severity of these lesions are significantly higher than in individuals with early-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) or in healthy populations. According to multiple studies, inflammatory-destructive changes of the oral mucosa occur in up to 89.7% of CRF patients, compared to only 15% in healthy controls.The most frequently reported symptom is xerostomia, or subjective oral dryness, which affects 76.4% to 87.5% of CRF patients, depending on dialysis modality and duration. Objective sialometry confirms this finding, with unstimulated salivary flow rates as low as 0.11 mL/min in hemodialysis patients, compared to 0.29 mL/min in healthy individuals (p < 0.001). Reduced salivary volume is accompanied by altered composition, including increased concentrations of urea, ammonia, and inflammatory proteins, leading to desiccation, mucosal irritation, and impaired wound healing.Among the notable clinical entities, uremic stomatitis remains a distinctive marker of severe azotemia. It typically manifests when blood urea levels exceed 150 mg/dL and presents with painful ulcers, hemorrhagic crusts, and pseudomembranous lesions on the tongue, buccal mucosa, and palate. Although less prevalent in the modern dialysis era, uremic stomatitis was observed in 9.6–35.2% of CRF patients in the cited studies.Oral candidiasis is another common complication, with a prevalence ranging from 39.1% to 64.7% among CRF patients undergoing dialysis or immunosuppressive therapy. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata were the most frequently isolated species, often associated with burning sensations, white plaques, and angular cheilitis. These infections are facilitated by both salivary hypofunction and impaired mucosal immunity, especially in patients receiving corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors.Gingival hyperplasia is more frequently encountered in transplant recipients (40.0%) than in dialysis patients (36.7%), and is typically associated with cyclosporine or tacrolimus use. Histological examination reveals epithelial hyperproliferation, fibroblast activation, and increased collagen deposition. Clinically, it leads to aesthetic and functional impairment, such as difficulty in mastication, speech, and oral hygiene.Erosive lichen planus—though less common was identified in 17.6% of hemodialysis patients, typically presenting with painful, keratotic patches and ulcerations, particularly on the buccal mucosa. The exact etiopathogenesis remains unclear, but it is likely mediated by T-cell dysregulation and chronic antigenic stimulation.From a microbiological perspective, oral dysbiosis is a defining feature of CRF. Quantitative cultures and PCR-based identification demonstrate a significantly higher prevalence of pathogenic species, including:• Candida albicans (39.1% in HD, 51.4% in transplant patients)• Porphyromonas gingivalis (27.3% in HD)• Tannerella forsythia (19.5% in HD)• Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus faecalis in mixed infectionsThese pathogens were almost absent in control individuals, highlighting the role of immunosuppression, acidic salivary pH, and nutrient-rich substrates (urea, ammonia) in promoting microbial overgrowth.Periodontal clinical indices further illustrate the oral disease burden in CRF:• Probing pocket depth (PPD): 4.28 ± 1.19 mm in hemodialysis vs. 2.63 ± 0.78 mm in controls (p < 0.001)• Clinical attachment loss (CAL): 3.91 ± 1.07 mm vs. 2.02 ± 0.65 mm in controls (p < 0.001)• Bleeding on probing (BOP): 72.4% in HD vs. 32.1% in controlsCytological studies further support these findings. Inflammatory-desquamative changes such as epithelial thinning, nuclear pyknosis, and neutrophil infiltration were observed in 87.1% of CRF patients with mucosal lesions. These structural changes compromise epithelial barrier integrity and potentiate microbial translocation, perpetuating the inflammatory cycle.In summary, the clinical and microbiological profile of oral mucosal disease in CRF reflects the cumulative effects of systemic immunosuppression, salivary dysfunction, and microbial imbalance. These manifestations are not limited to localized discomfort but represent a potential source of systemic inflammation, malnutrition, and infection. The routine documentation of periodontal parameters, cytological findings, and microbiological cultures should be an integral component of the nephrology-dental interface, enabling timely diagnosis and personalized therapy.Biochemical and cytokine biomarkers in oral diagnostics for CRFThe accurate and early diagnosis of oral complications in chronic renal failure (CRF) patients requires objective biomarkers that reflect the immunological and metabolic status of the oral mucosa. Saliva, as a readily accessible biological fluid, offers a non-invasive medium for assessing the biochemical and immunological environment of the oral cavity. Among various biomarkers, lactoferrin, albumin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and urea concentrations have been established as critical indicators of disease activity and mucosal vulnerability.Salivary lactoferrin, a key component of innate mucosal immunity, plays a pivotal role in antimicrobial defense and epithelial protection. However, in CRF, despite elevated absolute levels of lactoferrin due to compensatory glandular activity or vascular transudation, its diagnostic utility increases when normalized to salivary albumin, which reflects mucosal permeability and protein leakage. The lactoferrin/albumin ratio is significantly lower in CRF patients (2766.9 ± 512.7 µg/mg) compared to CKD patients without renal insufficiency (11766.3 ± 1245.2 µg/mg) and healthy controls (11510.7 ± 1034.3 µg/mg), indicating suppressed local immunity.In addition to structural proteins, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α are markedly elevated in the saliva and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) of CRF patients. IL-6, a proinflammatory mediator that promotes epithelial apoptosis and neutrophil recruitment, is significantly correlated with the severity of mucosal inflammation. Salivary IL-6 levels reached 32.8 ± 7.4 pg/mL in CRF patients, compared to 13.5 ± 3.9 pg/mL in healthy individuals (p < 0.01).Salivary urea concentration, a direct surrogate of systemic azotemia, is also significantly elevated in CRF. Urea diffuses passively from plasma into saliva, leading to mucosal irritation, pH reduction, and microbial dysbiosis. In hemodialysis patients, salivary urea levels can reach 14.2 to 15.2 mmol/L, compared to 3.6–5.8 mmol/L in healthy controls. This increase correlates strongly with xerostomia severity and epithelial desquamation.Furthermore, the decrease in salivary pH (mean: 6.03 ± 0.24 in CRF vs. 6.82 ± 0.12 in controls) creates an acidic environment that facilitates the growth of Candida spp. and proteolytic bacteria, aggravating mucosal injury and impairing healing responses.In the post-transplant population, TNF-α and IL-1β concentrations in GCF are also elevated, with TNF-α averaging 32.6 pg/mL and IL-1β up to 64.7 pg/mL, significantly higher than in non-renal patients. These cytokines serve not only as markers of inflammation but also potential predictors of periodontal tissue degradation and systemic inflammatory burden.Taken together, these salivary and crevicular biomarkers provide an integrative view of local and systemic processes in CRF. Their regular monitoring can inform diagnostic decision-making, guide individualized treatment planning, and assess therapeutic efficacy.

|

2. Conclusions

- The findings synthesized from multiple original studies provide compelling evidence that chronic renal failure (CRF) significantly impacts oral mucosal health through a constellation of systemic and local pathophysiological mechanisms. The oral manifestations in CRF—ranging from xerostomia and uremic stomatitis to candidiasis and periodontal degradation—are not merely incidental or hygiene-related phenomena but integral components of the systemic disease process.Immunologically, CRF is associated with a suppression of mucosal defense mechanisms, as evidenced by reduced lactoferrin/albumin ratios, increased cytokine levels (notably IL-6 and TNF-α), and elevated salivary urea concentrations. These changes are accompanied by altered salivary flow and composition, epithelial desquamation, and microbiological dysbiosis, all of which contribute to a chronic inflammatory environment in the oral cavity.Clinically, CRF patients exhibit high rates of mucosal lesions, gingival bleeding, attachment loss, and fungal infections—often in the absence of overt local risk factors. The strong correlation between periodontal parameters and renal function markers (urea, PTH, CRP) confirms the bidirectional relationship between oral and systemic health.Biomarker analysis, especially of saliva and gingival crevicular fluid, has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment planning. Salivary IL-6 and the lactoferrin/albumin index offer promise as non-invasive indicators of oral immune competence and inflammation severity.Therapeutically, a multidisciplinary, nephrology-integrated dental management approach is required to effectively address the oral health needs of CRF patients. This includes routine oral screening in nephrology clinics, pre-dialysis dental clearance, targeted antimicrobial protocols, cytokine-guided intervention, and personalized remineralization strategies.Ultimately, recognizing oral health as an essential component of systemic disease management in CRF can enhance patient outcomes, reduce healthcare burdens, and improve quality of life.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML