-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(6): 1717-1724

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251506.19

Received: May 12, 2025; Accepted: Jun. 2, 2025; Published: Jun. 5, 2025

Modern Aspects of Personalized Biliary Drainage in Malignant Mechanical Jaundice

Khujabayev Safarboy Tuktabaevich, Urozov Numоnjon Sadullayevich

Samarkand State Medical University, Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Malignant obstructive jaundice caused by hepatopancreatoduodenal tumors remains a major clinical challenge requiring prompt biliary decompression. This study justifies a differentiated approach to the use of minimally invasive drainage techniques (endoscopic and percutaneous) in 120 patients with inoperable malignancies. The results demonstrate that individualized selection of drainage method based on the level of obstruction significantly improves clinical efficacy, reduces complication rates, decreases the need for reinterventions, and enhances survival compared to uniform treatment strategies.

Keywords: Obstructive jaundice, Malignant biliary obstruction, Endoscopic stenting, Differentiated approach

Cite this paper: Khujabayev Safarboy Tuktabaevich, Urozov Numоnjon Sadullayevich, Modern Aspects of Personalized Biliary Drainage in Malignant Mechanical Jaundice, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 6, 2025, pp. 1717-1724. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251506.19.

1. Introduction

- Malignant (obstructive) jaundice of tumor etiology is a frequent and severe complication of malignant tumors in the hepatopancreatoduodenal zone. By the time jaundice manifests, most of these tumors are considered inoperable, and radical surgery becomes impossible. Without adequate bile drainage, patients quickly develop liver failure, cholemia, and the onset of cholangitis may lead to sepsis. Mortality without drainage is extremely high, making timely biliary decompression a vital part of palliative care for such patients.The modern stage of surgical gastroenterology development is characterized by a shift towards minimally invasive interventions for biliary decompression. Traditional open surgical bypass anastomoses (choledocho- or hepaticojejunostomy) in the context of malignant obstruction are associated with a high complication rate (up to 30%) and perioperative mortality of 3-15%. In contrast, endoscopic and percutaneous drainage have proven to be effective and relatively safe methods, allowing for reduced bilirubin levels, elimination of cholemia, and prevention of purulent complications. Endoscopic transpapillary stenting (via ERCP) is considered the method of choice for distal biliary obstructions caused by tumors in the area of the Vater's papilla or pancreatic head. If the tumor is located high (hilar cholangiocarcinoma, Klatskin tumor), endoscopic drainage is difficult and often incomplete; in such cases, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiostomy (PTCS) is prioritized. Both approaches—endoscopic and percutaneous—are minimally invasive and collectively allow for effective jaundice relief in most patients. However, several unresolved questions remain regarding the optimal strategy. The main issue is the selection of the drainage method for a specific patient based on the anatomy of the tumor obstruction. A uniform approach (e.g., only external drainage or only endoscopic stenting for all patients) does not take into account the differences in the location of the block and the condition of the intrahepatic ducts. This can lead either to unjustified risks (attempts at endoscopic drainage of complex hilar strictures) or inadequate decompression (by draining only one lobe of the liver in the case of bilobar obstruction). It is known that incomplete drainage of all affected ducts leads to retention of obstruction in the liver lobe and the risk of purulent complications. Even with the success of the intervention, if a significant portion of the liver remains undrained, bile hypertension persists in these segments, often leading to cholangitis and deterioration in survival rates. On the other hand, overly aggressive tactics (such as the installation of multiple stents for multi-level strictures) increase the invasiveness of the procedure and may increase the risk of complications, such as duct injury, bleeding, and infection. Therefore, a balance must be struck between the volume of drainage and the safety of the procedure.Optimizing palliative treatment of malignant jaundice consists of a differentiated approach—choosing the least traumatic and simultaneously sufficiently effective method of decompression for each patient. Literature shows that for proximal (hilar) tumor strictures, adequate improvement in bile flow is achieved by draining at least 50% of the functional liver volume. Drainage of >50% of liver volume correlates with significant bilirubin decline and fewer cholangitis episodes. This is usually achieved by installing two stents (bilateral drainage of the right and left lobes) in patients with Bismuth II-III tumors of the liver hilum, while for more complex strictures (Bismuth IV), drainage of three branches (right anterior, right posterior, and left lobe) may be required. However, draining inevitably non-perfused or atrophied liver segments is unfeasible, as it does not improve function and only increases the risk of infections. In cases of distal obstructions, it is sufficient to stent one common bile duct, restoring flow from the entire liver. Therefore, when planning an intervention, the shape and level of tumor obstruction (according to the Bismuth-Corlette classification and cholangiography data) should be considered, and the goal should be to achieve complete drainage of all functioning liver lobes.Another factor is the patient’s overall condition and comorbidities. In weakened patients with high operative risk, the least invasive method should be preferred. Typically, endoscopic stenting is better tolerated than external drainage with catheter placement through the skin. Internal stents avoid the continuous loss of bile outside, electrolyte imbalances, and the inconvenience of caring for a drainage tube. Therefore, when technically feasible, endoscopic stenting is preferred, especially in elderly patients and those with significant comorbidities. On the other hand, in cases of severe cholangitis, markedly enlarged intrahepatic ducts, or after gastrectomy (disrupted anatomy for ERCP), percutaneous methods are more direct and faster for decompression.Thus, the relevance of the problem lies in the need to develop an algorithm for selecting the method of minimally invasive bile drainage, taking into account the individual characteristics of the tumor obstruction. A differentiated approach should improve treatment efficacy—reduce drainage failure rates, decrease complications (especially purulent ones), and enhance the quality of life for patients. Furthermore, adequate biliary decompression is a prerequisite for subsequent chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which may prolong the lives of patients with advanced tumors. Therefore, substantiating the optimal strategy for minimally invasive drainage in malignant jaundice is of great clinical interest and practical significance.Study Objective. To justify a differentiated approach to the application of minimally invasive biliary drainage techniques in patients with inoperable malignant tumors of the hepatopancreatoduodenal zone complicated by mechanical jaundice.

2. Materials and Methods

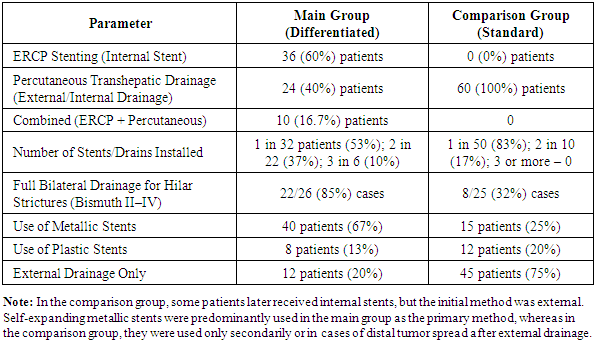

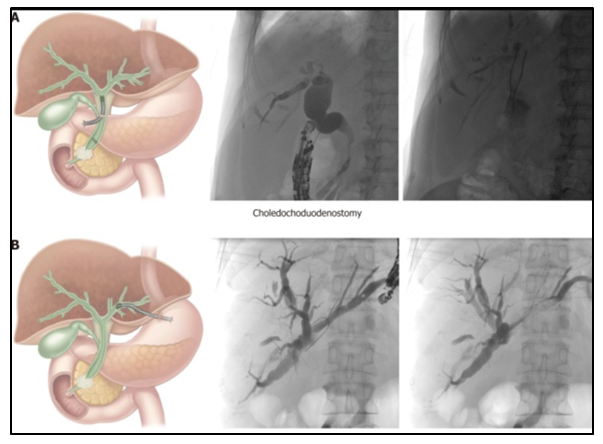

- The study was conducted at the departments of abdominal surgery and endoscopy and included 120 patients with mechanical jaundice caused by malignant tumors of the hepatopancreatoduodenal region (pancreatic head cancer, distal cholangiocarcinomas, tumors in the BDS area, proximal cholangiocarcinomas, and others). Inclusion criteria were as follows: clinical and laboratory signs of obstructive jaundice (total bilirubin >50 µmol/L, cholestatic syndrome), the presence of an inoperable tumor (based on imaging methods—CT/MRI—locally advanced or metastatic tumor deemed unresectable by a consensus), and technical feasibility for minimally invasive drainage. Patients with benign strictures, resectable tumors (planned for radical surgery), or previously drained bile ducts were excluded.All patients signed informed consent for the intervention. The patients were randomized into two groups, each with 60 participants. The main group included patients for whom the biliary drainage strategy was determined individually based on the level of blockage and tumor characteristics (differentiated approach). The comparison group included patients who underwent standardized drainage (without considering the differences in obstruction anatomy). The average age of patients was 64±9 years, with 65 (54.2%) men and 55 (45.8%) women.In the main group, the following protocol was applied. For distal obstructions (tumors of the ampulla or pancreatic head), the first step was performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiostomy with the installation of an internal stent in the extrahepatic bile ducts (via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, ERCP). Self-expanding metallic stents with a diameter of 8–10 mm were used; the choice of metallic stents was due to their larger lumen and longer patency in oncological patients. For proximal tumors (hilar cholangiocarcinoma), preference was given to percutaneous transhepatic drainage under ultrasound and X-ray control. The Bismuth classification was applied: for types II–III, bilateral stenting was performed for the left and right systems (through separate punctures) to ensure drainage from both liver lobes; for type IV, three sectors (left lobe, right anterior, and right posterior sectors) were drained with the installation of three stents. A combination of endoscopic and percutaneous methods was allowed in one patient (so-called combined drainage)—for example, in a Klatskin tumor, an endoscopic stent was first placed in the left duct, followed by percutaneous drainage of the segmental ducts of the right lobe. If endoscopic intervention was technically unsuccessful (inability to catheterize the ducts due to complete obstruction, BDS stenosis, post-gastrectomy status, etc.), the patient was switched to percutaneous drainage (thus, the method was changed to a more suitable one within the framework of a differentiated strategy). In all cases, the goal was to achieve decompression of as much functioning liver parenchyma as possible. Full drainage was considered if total bilirubin decreased by >50% from baseline within two weeks.In the comparison group, all patients underwent standard single-stage drainage following the protocol previously adopted in the clinic: percutaneous transhepatic cholangiostomy with the installation of an external drainage system in one of the liver systems. Typically, the expanded right hepatic duct was punctured, followed by drainage of the right lobe; for left-sided tumors, the left hepatic duct was punctured. Endoscopic intervention was not performed at this stage in the comparison group. Thus, the strategy did not involve mandatory bilateral or combined drainage; most patients in this group had only one liver lobe drained (unilateral bile drainage). After external drainage and bilirubin reduction, internal stents were placed in the comparison group if necessary (via the formed fistula track, the "rendezvous" method), but for the purpose of the analysis, the initial results were evaluated only after the first stage (primary decompression).Patients in both groups were monitored dynamically. Laboratory parameters (bilirubin levels, alkaline phosphatase, transaminases) were evaluated before and after the intervention (on the 1st, 3rd, 7th days, and 2 weeks). The technical success of the procedure was defined as the installation of the drainage system in the bile ducts with restoration of bile flow. Clinical success was defined as the reduction in the severity of jaundice and intoxication in the following 1–2 weeks, confirmed by a reduction in bilirubin >50%. All complications related to the intervention were recorded: acute cholangitis, acute pancreatitis (for endoscopic procedures), bleeding (intraluminal or into the cavity requiring blood transfusion), peritonitis or abdominal abscesses, incorrect stent placement or migration, early stent occlusion, and fatal outcomes within 30 days after the intervention. In the long-term period (the average follow-up period was 10 months), the frequency of recurrent obstruction (restenosis or stent occlusion), the need for repeated interventions (stent replacement in case of occlusion or displacement, installation of additional drains in case of obstruction progression), and overall patient survival (6- and 12-month survival) were assessed. Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate survival, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Statistical processing was performed using StatTech® software; group comparisons were made using χ² and Student’s t-test, with a significance level of p<0.05. The ethics committee approved the study, and it adhered to the Helsinki Declaration.

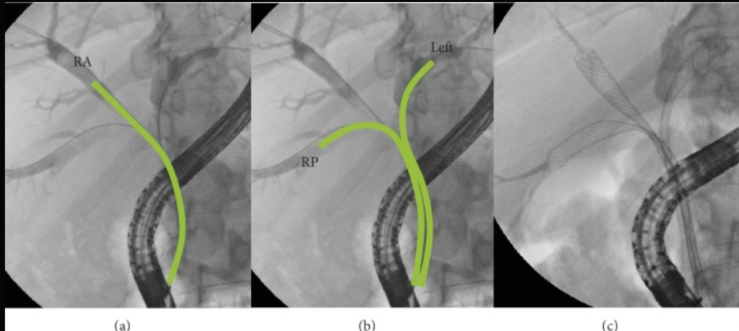

| Figure 1. Schematic of Differentiated Drainage Tactics |

3. Results and Discussion

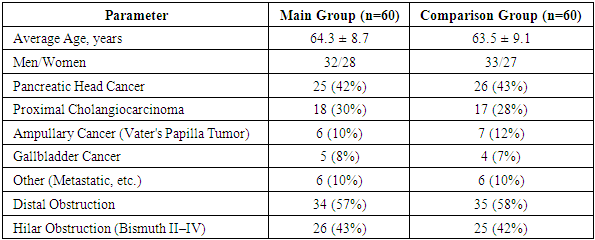

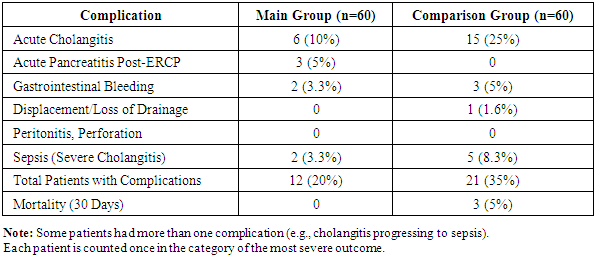

- Both groups were comparable in basic characteristics. In the main group, the average age was 64.3±8.7 years, with 32 men (53%), while in the comparison group it was 63.5±9.1 years, with 33 men (55%) (p>0.5). The etiology of obstruction was as follows: pancreatic head cancer – 25 cases (42%) in the main group and 26 (43%) in the comparison group; proximal cholangiocarcinoma (liver hilum tumor) – 18 (30%) vs 17 (28%); ampullary cancer (Vater's papilla tumor) – 6 (10%) vs 7 (12%); gallbladder carcinoma with cholangiocathesis – 5 (8%) vs 4 (7%); metastatic biliary tree lesions (lymph nodes of the hilum, stomach cancer, etc.) – 6 (10%) vs 6 (10%). The level of biliary tract blockage: distal obstruction (below the confluence of the hepatic ducts) was noted in 34 (57%) and 35 (58%) patients in the main and comparison groups, respectively; hilar obstruction (Bismuth II–IV) – in 26 (43%) vs 25 (42%) patients. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups for these indicators (p>0.1), confirming the correctness of the comparison.In the main group, the planned drainage was performed in 58 out of 60 patients (96.7%). Two patients required a change of method: in one case, during the attempt to perform ERCP stenting for the tumor in the lower third of the choledochus, catheterization of the papilla failed due to infiltration of the duodenal wall, and the patient was successfully drained percutaneously; in another case, with a Bismuth IV hilar tumor, after two stents were installed, obstruction of a segmental duct remained, requiring additional puncture drainage. In the comparison group, the technical success of the primary procedure was achieved in 54 out of 60 patients (90%): 6 patients were unable to drain the bile ducts on the first attempt due to technical difficulties (severe cholangitis, obstruction of the duct lumen with pus, inability to pass the guide through the tumor) – they underwent repeated attempts, counted as complications. The difference in technical success (96.7% vs 90%) was not statistically significant (p=0.12), but the trend in favor of the differentiated approach was evident.Clinical success (significant reduction in jaundice in the following 14 days) was observed in 55 (91.7%) patients in the main group, which was significantly higher than 48 (80%) in the comparison group (χ²=4.0; p=0.045). Thus, the differentiated approach allowed for full biliary decompression in nearly 92% of patients. In the comparison group, one in five patients did not achieve sufficient effect from the first intervention (high bilirubinemia persisted), requiring additional measures.The main cause of incomplete clinical effect in the comparison group was inadequate liver volume drainage. For proximal strictures, when only one half of the biliary tree was drained (e.g., only the right duct), several patients still had obstruction in the contralateral lobe, leading to persistent hyperbilirubinemia and episodes of cholangitis. In the main group, thanks to bilateral drainage in the same situations, bile flow from both the right and left lobes was ensured (complete bile drainage). As a result, the proportion of patients with full decompression (defined as drainage of ≥50% of liver parenchyma) in the main group significantly exceeded that in the comparison group (92% vs 80%, see above).Following the interventions, a significant reduction in total bilirubin levels was observed in most patients in both groups (Figure 2). Initially, the average serum bilirubin concentration was 256±98 µmol/L (main group) and 249±105 µmol/L (comparison group), p=0.74. By day 3 after drainage, bilirubin reduction in the main group was more pronounced: to 152±80 µmol/L vs 180±95 µmol/L in the comparison group (p=0.08). By day 7, bilirubin levels in the main group decreased by an average of 71% from baseline and reached 74±45 µmol/L, while in the comparison group, the decrease was 55%, to 112±60 µmol/L, p=0.04. In 11 patients from the comparison group, significant hyperbilirubinemia (>100 µmol/L) persisted after a week, while in the main group, this was seen in only 5 patients. Bilirubin normalization (<20 µmol/L) was achieved in 40 patients (67%) in the main group and 32 (53%) in the comparison group. Similar dynamics were seen for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and GGT levels: in the main group, the average ALP decreased to 280 U/L after 2 weeks, in the comparison group to 400 U/L (initially ~600–650 U/L in both groups). Therefore, the individualized strategy led to a faster resolution of cholestasis.

| Figure 2. Fluoroscopy of the Stages of Endoscopic Drainage of Proximal Obstruction (Diagram of Three Images) |

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- 1. Individual selection of the drainage method (endoscopic, percutaneous, or their combination) based on the level and extent of the tumor obstruction results in clinical success in 91.7% of cases, significantly higher than the standardized strategy (80%, p<0.05).2. In the differentiated approach, bile drainage from ≥50% of the liver volume was achieved in 92% of patients, while in the unilateral approach, this was only achieved in 80%. This leads to more rapid bilirubin reduction (1.3 times more pronounced on day 7) and significantly fewer purulent complications.3. In the main group, complications occurred in 20% of patients, compared to 35% in the comparison group. Notably, the incidence of acute cholangitis decreased from 25% to 10%, with the relative risk reduced by 60%. There was also a trend towards a reduction in other complications, including early mortality (0% vs 5%).4. The differentiated approach reduced the need for repeat drainage or stent replacement in the long term by two times (18% vs 40%, p<0.01). This facilitates patient management and reduces the burden on the hospital.5. With the individualized approach, there is a trend towards increased survival: the median overall survival increased from 7.2 to 9.8 months, and 1-year survival increased from 20% to 30%. Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, it is clinically important and related to a wider use of chemotherapy after successful decompression.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML