-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(4): 1223-1226

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251504.77

Received: Mar. 26, 2025; Accepted: Apr. 20, 2025; Published: Apr. 26, 2025

Surgical Treatment of Complicated Sacrum Tumors Annotation

Polatova Djamilya Shogayratovna 1, Alimov Ijod Rustamjonovich 2, Khamrokulov Bekzod Bahodirovich 3

1Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Oncology and Medical Radiology, Tashkent Dental Institute, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Doctor of Philosophy in Medical Sciences, Associate Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Center for the Development of Professional Qualification of Medical Workers, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

3Basic Doctoral Student, Department of Neurosurgery, Center for the Development of Professional Qualification of Medical Workers, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Tumor lesion of the sacrum with the presence of compression of the nerve roots sharply worsens the quality of life of patients. Surgical treatment of tumors of this localization has a number of complex tasks, including radical removal of the tumor with low blood loss, release of nerve roots and restoration of the integrity of the pelvic ring.

Keywords: Sacral tumors, Surgical treatment

Cite this paper: Polatova Djamilya Shogayratovna , Alimov Ijod Rustamjonovich , Khamrokulov Bekzod Bahodirovich , Surgical Treatment of Complicated Sacrum Tumors Annotation, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 4, 2025, pp. 1223-1226. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251504.77.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Tumor lesions of the sacrum are relatively rare and account for 1-7% of all spinal tumors. Plasmocytomas, chordomas and chordosarcomas predominate among sacral tumors, as well as tumors in other bone skeletal localities. The detection of tumors of this localization is usually carried out when the tumor reaches a significant size. Therapeutic tactics depend to a certain extent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, its histological characteristics, and its spread to surrounding tissues. [2] After radical removal of tumors, the recurrence rate is much lower, the life expectancy is much longer. [3] Radical surgical removal of sacral tumors requires performing volumetric operations, during which the stability of the pelvic ring is disrupted, nerve structures may be damaged and a large amount of circulating blood may be lost. With such interventions, decompression of nerve roots is performed, the tumor is removed, the spine with the pelvic ring is fixed. [4]

2. The Purpose of the Study

- Development and implementation of surgical interventions involving radical removal of sacral tumors without major blood loss, decompression of nerve structures, fixation of the spine.

3. Materials and Methods of Research

- The study was conducted at the clinical bases of RSNPMTSOIR and RSNPMTSNH in 36 patients treated in the period 2010-2020. We have divided the patients into 2 groups. Group 1 consisted of 13 patients who underwent surgery to remove the tumor in a single unit. Of these, 10 patients had large tumors with lesions of the entire sacrum (SI–SV vertebrae), 2 patients had lesions of the upper sacral vertebrae (SI–SIII), 1 patient had lesions of the lower sacral vertebrae (SIII–SV). Lumbo-pelvio fixation was performed in 12 patients after removal of the tumor. Group 2 consisted of 23 patients in whom the tumor was removed by "lumping". In 10 of them, large tumors with lesions of the entire sacrum (SI–SV) were detected, in 8 patients of the upper sacral vertebrae (SI–SIII), in 5 patients of the lower sacral vertebrae (SIII–SV). Lumbo-pelvio fixation was performed in 6 patients after removal of the tumor. CT, MRI, and electroneuromyography were performed from instrumental examination methods. Before the operation, clinical and neurological symptoms were comprehensively studied. Also, in the early postoperative period, all patients underwent control studies, in particular radiography, CT or MRI, neurological symptoms were evaluated in detail. In the long-term period, the results of treatment of 13 patients (group 1) who had a tumor removed by a "block" were compared with the results of treatment of 23 patients (group 2) with sacral tumors operated on for removal by "lumping" the tumor. The average duration of follow-up was 3 years. Data in the long-term period were obtained in 29 patients. All patients underwent control MSCT and MRI.

4. The Results of the Study

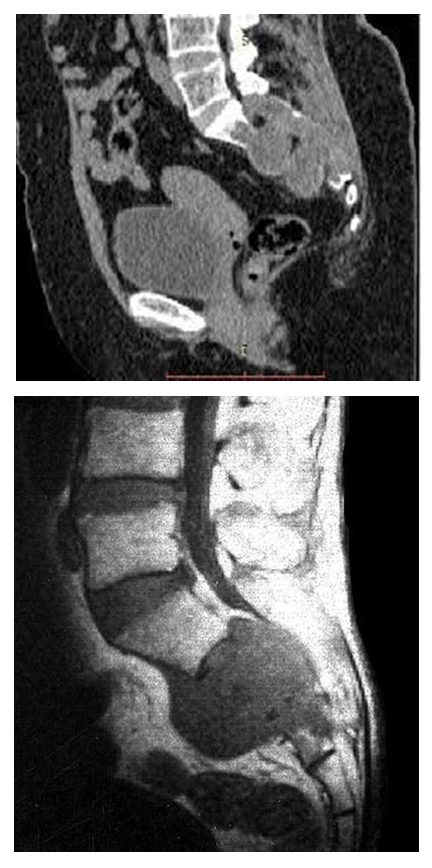

- The earliest symptom of sacral tumors was local pain in the sacral region. With the progression of the tumor, root symptoms appeared. With compression of the SI roots, typical manifestations of scialgia, SII–SIV roots, pelvic organ disorders occurred, in far advanced stages, radiculopathy of all sacral roots (SI–SV), pronounced root pain were typical. On a 5-point scale in group 1, radicular pain syndrome averaged 2.3 points, sensory radicular disorders 3.1 points, motor radicular disorders 3 points; on a 3-point scale, pelvic disorders before surgery averaged 2.2 points. In group 2, radicular pain syndrome was 2.5 points, sensory radicular disorders 3.3 points, motor radicular disorders 3.4 points; on a 3-point scale before surgery, pelvic disorders averaged 2.1 points. With the help of MSCT and MRI, both the sacral tumor itself and the direction and volume of its spread were diagnosed. In most situations with sacral tumors, the combined use of MSCT and MRI was necessary. According to the MSCT data, it was possible to fully assess the bone structure of the sacrum, the structure of the pelvis. The advantage of MRI was the assessment of soft tissues, the tumor itself, and neural structures. According to the results of MSCT and MRI, surgical intervention, access, and necessary fixation were planned (Fig. 1, 2).

| Figure 1-2. MSCT, MRI of a tumor lesion of the sacral vertebrae |

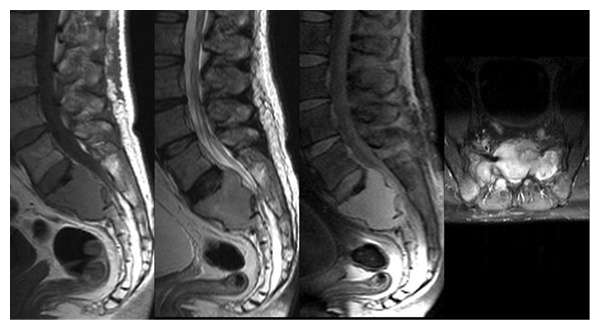

| Figure 3. MRI. The tumor affects the SI-SII vertebrae with epidural and presacral spread of the tumor |

| Figure 4. Postoperative X-ray of the patient after lumbo-pelvio fixation |

| Figure 5. Postoperative MSCT image of the patient after lumbo-pelvio fixation |

5. Discussion

- Previously, it was found that only radical interventions provide a significant increase in the average life expectancy of patients with sacral tumors. [5] The technique of radical resection of sacral tumors with a block was introduced by B. Stener, B. Gunterberg. [6] The authors emphasized that the purpose of the operation is to resect the tumor with a sacral block with the inclusion of unaffected tissues around the circumference of the tumor. In accordance with generally accepted principles, sacral resection should be performed one segment above the rostral border of the tumor. High resection of the sacrum is technically more complicated, associated with large blood loss, instability of the pelvic ring and lumbar spine, functional disorders due to damage to the SI-SV roots. [7] Sacral resection using combined posterior and anterior transperitoneal access was described by S. McCarty and co-authors. [8] Currently, many authors also prefer two-stage interventions. [9] Currently, the most popular technique of high resection of the sacrum by Stener and Gunterberg. Recently, neurosurgeons, performing sacral resection, preserve all sacral roots. [10] At the same time, it is impossible to remove the sacrum in a single block and not damage the roots when using a single access. In this regard, combined front and rear accesses are used. [11] After a high resection of the sacrum, the stability of the pelvic ring, the connection of the lumbar spine with the sacrum, is always disrupted. Upon completion of the stage of tumor removal and high resection of the sacrum, a stabilizing operation is necessary. [12] Our studies have also convincingly demonstrated an increase in the duration of the period without recurrence of the tumor after its radical removal. Thus, the results of treatment and prognosis in the presence of malignant sacral tumors are better after performing radical operations, reliable intraoperative fixation of the spine with a pelvic ring, the use of radiation treatment and chemotherapy after surgery.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML