Urinov Muso Boltayevich, Dagayeva Dilfuza Botirovna

Bukhara State Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Dagayeva Dilfuza Botirovna, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Objective: This study was to evaluate pain management strategies used by primary care patients with chronic low back pain) as an adjunct to medical diagnosis before a physical therapy program. Material-Methods: A total of 68 people were divided into 3 age groups: young people (18-44 years old), middle-aged people (45-59 years old) and elderly people (over 60 years old). Results: Patients complained of CLBP for an average of 11.32±6.81 years. The most common strategies for dealing with back pain included declaring that pain is manageable, prayers and hopes, and increased behavioral activity. Statistically significant differences in coping strategies were found between age groups. Older patients were more likely to claim pain management compared to younger age groups (p<0.01). People over the age of 60 were more likely to report active pain management, while younger people reported catastrophization. Conclusions: Patients of different age groups experienced various difficulties in overcoming pain. Most of them needed support in self-management of pain in addition to physical therapy. The basic assessment of pain management strategies should be consistently taken into account and included in rehabilitation protocols for the treatment of chronic pain.

Keywords:

Adaptation, Psychological, Lower back pain, Physical and rehabilitation medicine, Primary health care

Cite this paper: Urinov Muso Boltayevich, Dagayeva Dilfuza Botirovna, Primary Care for Chronic Low Back Pain as an Adjunct to Medical Diagnosis, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 3, 2025, pp. 628-631. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251503.30.

1. Relevance

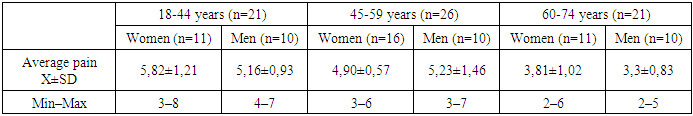

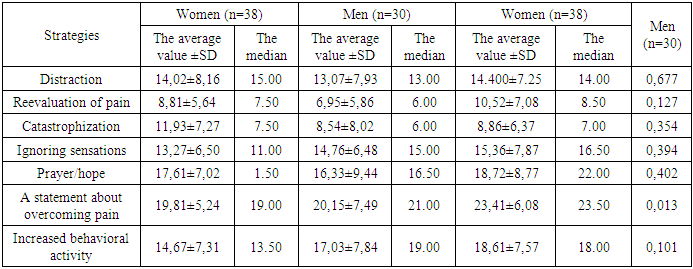

The growing prevalence of back pain diagnosis among people of different ages working in highly developed/industrialized countries highlights the need for new treatment methods [1,5]. Highly effective treatment has become a problem for both the healthcare system and people suffering from back pain, for example, patients need to rely less on self-help and be more proactive in seeking professional help and support regarding their treatment and pain control. However, some aspects of the diagnostic process and effective treatment are still unclear. Consequently, the adaptation of examination protocols and therapeutic programs that take into account interdisciplinary diagnosis and the multidimensional structure of pain is becoming increasingly important [6,7]. In fact, a superficial attitude towards the biopsychological approach to the treatment of chronic pain can lead to patient disappointment with the results of treatment [1,8].Coping with pain is an important element of pain perception and response. Behavioral efforts refer to measures taken to reduce pain, while cognitive efforts focus on rethinking pain or seeking distraction. Previous studies have demonstrated poor treatment outcomes in patients who used passive coping strategies [8,10]. Passive pain management, catastrophization, avoidance, depression, and anxiety are important predictors of problems adapting to chronic pain and the resulting further psychosocial problems [1,2,11]. Moreover, a passive coping strategy is accompanied by low self-efficacy, higher pain intensity, and disability [10].Age is considered one of the risk factors for low back pain (PD), as its prevalence increases with age [4,5]. For young people, pain is often associated with a sense of disability, decreased performance (loss of productivity), unemployment, and a serious limitation affecting the process of self-realization. On the other hand, elderly people suffering from pain are subject to functional limitations, economic difficulties, and social isolation [1,4]. In the present study, an attempt was made to adopt a different perspective on the development of research focused on the adaptation of rehabilitation protocols and modification of therapeutic programs for the rehabilitation of lumbar pain. The authors of the following study suggested that patients with chronic back pain need strategies to manage pain and its effects, since pain management is not limited to one dimension of human functioning (cognitive, affective, behavioral, physiological) [11]. This can have significant results in the process of physical therapy and its long-term effectiveness.The purpose of this study was to evaluate self-control and pain management strategies in patients with CLBP awaiting rehabilitation immediately before starting a treatment program. The overall mental health assessment appears to be sufficient for rehabilitation needs. The following hypotheses were analyzed:• What pain management strategies do patients with chronic low back pain use?• Does age influence the choice of certain strategies?• Are there links between the strategies chosen by the patient and his/her self-control and ability to relieve pain?Materials and methods: 68 patients participated in the study: 40 women and 28 men suffering from CLBP (associated with degenerative diseases). The diagnosis of lumbar spine degeneration was made on the basis of a clinical examination, confirmed by X-ray examination and MRI. The average height of the respondents was 166±11.30 cm, weight 79±14.33 kg, and BMI 28.58±3.36. The range of pain intensity (VAS 0-10 scale) before treatment in each group is shown in Table 1. The duration of back pain ranged from 4 months to 20 years, with an average of 11.32±6.81 years. The average waiting time for prescribed rehabilitation in primary care was 6.82±5.46 weeks. The most commonly recommended forms of treatment included individual or group exercises, interference currents, laser therapy, cryotherapy, and massage.Table 1. The range of pain intensity in the study groups before the start of treatment (VAS scale from 0 to 10)

|

| |

|

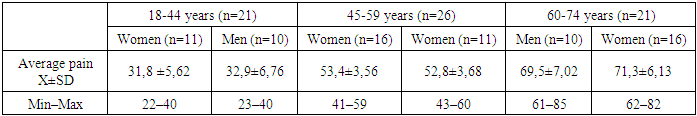

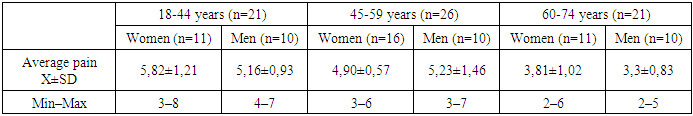

Criteria for inclusion in the study: chronic low back pain lasting more than 3 months, degenerative changes in the lumbar spine, absence of other acute conditions, referral to physical therapy from a doctor, consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria from the study were difficulties in contacting the patient, deeper mental disorders, other significant pain, and age under 20 years.According to the hypothesis, the results were analyzed for three age groups: young people (18-44 years old), middle-aged people (45-59 years old) and the elderly (60 years and older). The age groups were determined according to the periods of human development (Table 2).Table 2

|

| |

|

The authors of the questionnaire proposed six cognitive strategies: (1) distraction, (2) overestimation of pain sensation, (3) catastrophization, (4) ignoring sensations, (5) prayer/hope, and (6) declaring pain manageable, as well as one behavioral strategy (7) defined as increased behavioral activity. These strategies include three factors: (1) cognitive coping, (2) distraction and taking substitute steps, (3) catastrophization and the search for hope.In addition to evaluating the 42 statements above, the patients answered two questions regarding the assessment of their own self-control and ability to relieve pain. The scales were as follows: a Likert scale from 0 to 6 for 42 statements, where 0 means "I never do this" and 6 means "I always do this." Thus, for each strategy, the final scores ranged from 0 to 36 points. The higher the score, the more important the strategy is for the patient. Two additional questions related to pain control and relief were separately assessed by the respondent on a scale from 0 to 6, where 0 means "I have no control over the pain" (in the first question) and "I cannot relieve it" (in the second question), and 6 means "I have full control over the pain" and "I can reduce it completely," respectively. The higher the score, the more convinced the patient was of their ability to cope with pain. The Cronbach's alpha for the entire instrument was 0.80, and individual strategies exceeded this value. The exceptions were two strategies: distraction, 0.64, and increased behavioral activity, 0.63.

2. Results

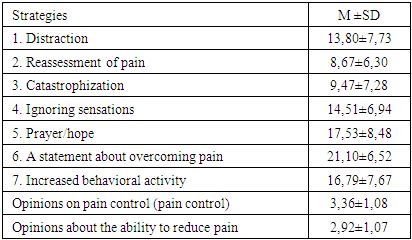

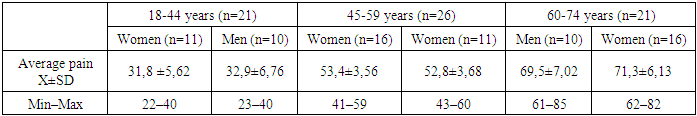

The results showed that the following strategies were the most popular among the examined patients: a statement that they were doing well, prayer and hope, as well as increased behavioral activity (Table 3).Table 3. Strategies used to combat pain (scale from 0 to 36 points), and opinions about pain control and relief (scale from 0 to 6 points) voiced by people suffering from chronic low back pain

|

| |

|

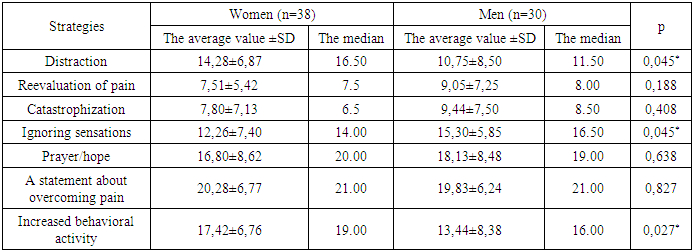

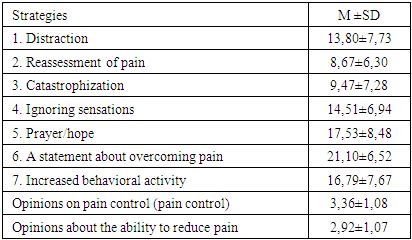

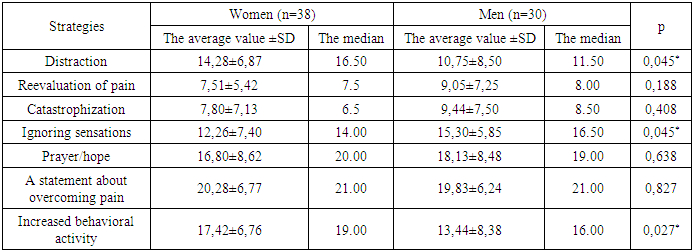

Choosing strategies for coping with chronic pain based on gender.Men and women tend to choose different strategies for coping with pain. Women were more likely than men to use distraction techniques (p=0.045) and showed greater behavioral activity (p=0.027). They were also less likely to ignore pain (p=0.045). No differences were noted for the other strategies (Table 4).Table 4. Gender differences in strategies used to overcome pain (average values)

|

| |

|

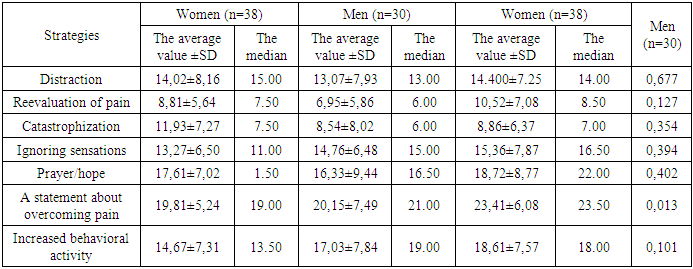

Regarding opinions about pain control and the possibility of pain reduction (two additional questions), although no gender differences were found, the authors analyzed the relationship between these opinions and strategies used to cope with pain in the same group of women and men. Among women, opinions about pain control skills were positively correlated with statements about coping (rho=0.352, p=0.01) and negatively with catastrophization (rho=-0.276, p=0.048), while feelings of effective pain reduction were positively associated with statements about coping (rho=0.352, p=0.01) and negatively with catastrophization (rho=-0.340, p=0.014).In the male group, pain control was positively correlated with prayer/hope (rho=0.484, p=0.003) and ignoring pain (rho=0.417, p=0.003). Pain reduction opinions correlated with overestimation of pain experience (rho=0.581, p=0.0001), increased behavioral activity (rho=0.712, p=0.0001), and distraction (rho=0.510, p=0.001).Table 5. Pain management strategies depending on the age of the subjects (average scores)

|

| |

|

The results of this study showed that the most frequently used strategies within the entire group were: declaration of self-control, prayer/hope, and increased behavioral activity. The least frequent strategies were: overestimation of pain sensation and catastrophization. The present study has revealed other gender differences in the choice of coping strategies. Women were more likely than men to use a strategy of distraction, as well as increased behavioral activity, and less likely to resort to ignoring pain. Thanks to the first two strategies, women were more likely to direct their attention to other activities to reduce or eliminate pain, which could be more effective than ignoring it. It should also be noted that women had negative correlations between pain control and the ability to reduce it and the strategy of catastrophization. Experiencing pain, as previously shown, becomes more common with age, and the aging of the modern population has health consequences. Studies of age-related differences in pain experience have provided an abundance of information. Although the differences regarding other strategies were not significant in the present study, it is worth highlighting several of them because of their clinical significance. Among the surveyed groups, young people were more likely to demonstrate catastrophization (passive coping). Ignoring pain and increased behavioral activity were the most rare. More severe catastrophization may interfere with pain control and reduction, and may be a predictor of chronic low back pain and poor adaptation to chronic pain. In addition, there was no association between pain control and the ability to reduce it in the younger group. Perhaps, in the case of prolonged pain in elderly patients, the ability to reduce it increases due to behavioral and cognitive strategies. This is evidenced by correlations between coping capabilities and strategies indicating a certain purposefulness of actions, such as influencing attitudes towards pain and increasing motivation to overcome it (the coping declaration), as well as distraction, overestimation of sensations and increased behavioral activity. The results obtained in the first age group may indicate that young people have some difficulty coping with pain compared to older people. These differences may be related to the fact that younger people show a more intense emotional response to pain than older people, who are better at distancing themselves from critical life events. The experience of pain by young people often significantly disrupts aspirations and goals in life and makes it difficult or impossible to meet various needs. Emotions related to both pain and its consequences cause anxiety, fear, and catastrophization.In primary medical practice concerning the musculoskeletal system, the most popular pain reduction procedures are physiotherapy and physical exercises (task strategy), but sometimes muscle tension relief achieved through relaxation, emotion relief (emotional strategy) or avoidance strategies may be more effective. This means that more emphasis should be placed on specialized treatment methods that should depend on the diagnosis of the patient's psychophysical condition, strategies used to deal with pain, the type of dysfunction, and the patient's living conditions. Positive changes in patients' beliefs about back pain, patients' awareness and knowledge of their mental state, and appropriate pain management techniques can make it easier for them to feel in control of pain and their own lives. Involving patients in the process of medical treatment/rehabilitation plays an important additional function, namely, it stimulates their activity, develops a sense of effectiveness, and also reduces anxiety and feelings of powerlessness and helplessness. The learned ways of dealing with pain will serve patients for a long time after the completion of therapeutic sessions conducted in the rehabilitation center.

3. Conclusions

The examined patients with CKD associated with degenerative diseases coped with pain in different ways during several weeks of waiting for prescribed physiotherapy. Most of them needed support in self-management of pain during this time and during the rehabilitation program. As the age of the respondents increased, the choice of more active pain management strategies was demonstrated. The main gender differences were as follows: women were more likely than men to use distracting strategies and behavioral activity, while men were more likely to report ignoring pain. Patients who coped better with pain demonstrated better self-control over pain. A basic assessment of pain management and self-control strategies should be included in rehabilitation protocols to better assess the patient's needs for chronic pain before ordering a treatment program.Information about the source of support in the form of grants, equipment, and drugs. The authors did not receive financial support from manufacturers of medicines and medical equipment.Conflicts of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

| [1] | Heiskanen T, Risto PR, Kalso E. Multidisciplinary pain management – Which patients benefit from it? Scandinavian Journal of Pain. 2012; 3 (4): 2017. |

| [2] | Linton S.J. Review of psychological risk factors for back and neck pain. Spine. 2008; 25 (9): 1148-56. |

| [3] | Hoy D., Brooks P., Blythes F., Buchbinder R. Epidemiology of lower back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015; 24: 769-81. |

| [4] | Wassilaki M., Hurvits E.L. A look at public health. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014; 73 (4): 122–26. |

| [5] | Akdag B, Cavlak U, Cimbiz A, Camdeviren H. Identification of risk factors for pain intensity among schoolchildren with nonspecific lower back pain. Med Sci Monit. 2017; 17 (2): PH12–15. |

| [6] | Epker J. Psychometric methods of pain measurement. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013; 27 (1): 30-48. |

| [7] | Tan G, Nguyen Q, Anderson KO, and others. Further review of the inventory of overcoming chronic pain. J Pain. 2009; 6 (1): 29-40. |

| [8] | Kaiser U, Arnold B, Pflingsten M, and others. Multidisciplinary pain treatment programs. J Pain Res. 2013; 6: 355–58. |

| [9] | Briggs AM, Jordan JE, O'Sullivan PB, et al. People with chronic low back pain have more difficulty engaging in a positive lifestyle than people without back pain: Health Literacy Assessment. BMC Musculoskeleton Disorder. 2018; 12: 161.10. |

| [10] | Pincus T, Kent P, Bronfort G, et al. Twenty—five years of the biopsychosocial model of low back pain - is it time to celebrate? Report from the twelfth International Forum on Primary Health Care Research for Low back pain. Spine. 2016; 3 (24): 2118–23. |

| [11] | Snelgrove S, Liossi C. Living with chronic low back pain: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Chronic Illn. 2013; 9 (4): 283–301. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML